Sam Gennawey's Blog

March 18, 2014

Universal Prolouge

ProlougeAct I“You can’t run scared and succeed in show business.”

1965 training manual Note from Jeff Kurtti October LAT 1984: October LAT 1984 Work in progress business week Ron Grover book Jay Stein was unrelated to Jules Stein. Los angeles times florida fund may invest in MCA park Kathryn harris 5201985 Work in progress sklar book Disneywar Wasserman book

1965 training manual Note from Jeff Kurtti October LAT 1984: October LAT 1984 Work in progress business week Ron Grover book Jay Stein was unrelated to Jules Stein. Los angeles times florida fund may invest in MCA park Kathryn harris 5201985 Work in progress sklar book Disneywar Wasserman book

Published on March 18, 2014 21:49

December 12, 2013

As they say...On Haitus

Hello

Thank you for visiting Samland.

Samland started as something of a lark some 3 1/2 years ago. I had just finished serving on the Pasadena Center Operating Committee board as kind of my professional hobby and was there during the $150 million dollar expansion. I am proud of that project and when it was completed it was time to move on and find something else. Since I was deep into planning documents at the time, I wanted to write about something a bit lighter. I really love Disneyland and the topic was familiar. I thought it would be a fun fun research project and it turned out to be the case. The stories that I wrote about were things that were of interest to me. I have been astonished that anybody else would also find these tidbits of interest. I am still astonished.

Samland started as something of a lark some 3 1/2 years ago. I had just finished serving on the Pasadena Center Operating Committee board as kind of my professional hobby and was there during the $150 million dollar expansion. I am proud of that project and when it was completed it was time to move on and find something else. Since I was deep into planning documents at the time, I wanted to write about something a bit lighter. I really love Disneyland and the topic was familiar. I thought it would be a fun fun research project and it turned out to be the case. The stories that I wrote about were things that were of interest to me. I have been astonished that anybody else would also find these tidbits of interest. I am still astonished.

One day, while planning for a trip to Walt Disney World, I was reading the Unofficial Guide and found a tip to use a disable FastPass machine at the Haunted Mansion for a freebie. You know what I am talking about. When the trick did not work, I wrote to Len Testa, co-author, and let him know. His reply was less about the FastPass machine but about an urban planner interested in Walt Disney World. We talked. He got me on the WDW Today podcast. That highlighted this blog. And, as they say the rest is history:

- The Disney Design side bars in The Color Companion to Walt Disney World.

- An essay entitled "The Evolution of Entertainment Retail" in Planning Los Angeles

- An essay entitled "Walt Disney's EPCOT and the Heart of Our Cities" in Four Decades of Magic

- Walt and the Promise of Progress City

- The Disneyland Story: The Unofficial Guide to the Evolution of Walt Disney's Dream

- I got in the index of Beth Dunlop's excellent Building a Dream

- Talks at The Walt Disney Family Museum, WDI, Disney Creative, USC, American Planning Association, many Disneyana clubs (love you guys), WDW leadership teams, and many others.

- The MiceChat weekly column called Samland

- The occasional lunch with Bob Gurr.

- The friendship of so many.

- Other stuff

I got to write books. I get to write books. For the geeky me, this has been a very cool thing. And some of you have bought the them. That is even cooler. I am in the midst of writing another one that will be out in the Fall of 2014 and I hope to continue writing books.

Therefore, this site, Samland's Disney Adventures will be on hiatus. To find out if the status changes I suggest you join The Disneyland Story page and that is where I will post the latest updates. As for MiceChat, it won't be every week but when there is something to say.

Thank you

Sam Gennawey

Thank you for visiting Samland.

Samland started as something of a lark some 3 1/2 years ago. I had just finished serving on the Pasadena Center Operating Committee board as kind of my professional hobby and was there during the $150 million dollar expansion. I am proud of that project and when it was completed it was time to move on and find something else. Since I was deep into planning documents at the time, I wanted to write about something a bit lighter. I really love Disneyland and the topic was familiar. I thought it would be a fun fun research project and it turned out to be the case. The stories that I wrote about were things that were of interest to me. I have been astonished that anybody else would also find these tidbits of interest. I am still astonished.

Samland started as something of a lark some 3 1/2 years ago. I had just finished serving on the Pasadena Center Operating Committee board as kind of my professional hobby and was there during the $150 million dollar expansion. I am proud of that project and when it was completed it was time to move on and find something else. Since I was deep into planning documents at the time, I wanted to write about something a bit lighter. I really love Disneyland and the topic was familiar. I thought it would be a fun fun research project and it turned out to be the case. The stories that I wrote about were things that were of interest to me. I have been astonished that anybody else would also find these tidbits of interest. I am still astonished.One day, while planning for a trip to Walt Disney World, I was reading the Unofficial Guide and found a tip to use a disable FastPass machine at the Haunted Mansion for a freebie. You know what I am talking about. When the trick did not work, I wrote to Len Testa, co-author, and let him know. His reply was less about the FastPass machine but about an urban planner interested in Walt Disney World. We talked. He got me on the WDW Today podcast. That highlighted this blog. And, as they say the rest is history:

- The Disney Design side bars in The Color Companion to Walt Disney World.

- An essay entitled "The Evolution of Entertainment Retail" in Planning Los Angeles

- An essay entitled "Walt Disney's EPCOT and the Heart of Our Cities" in Four Decades of Magic

- Walt and the Promise of Progress City

- The Disneyland Story: The Unofficial Guide to the Evolution of Walt Disney's Dream

- I got in the index of Beth Dunlop's excellent Building a Dream

- Talks at The Walt Disney Family Museum, WDI, Disney Creative, USC, American Planning Association, many Disneyana clubs (love you guys), WDW leadership teams, and many others.

- The MiceChat weekly column called Samland

- The occasional lunch with Bob Gurr.

- The friendship of so many.

- Other stuff

I got to write books. I get to write books. For the geeky me, this has been a very cool thing. And some of you have bought the them. That is even cooler. I am in the midst of writing another one that will be out in the Fall of 2014 and I hope to continue writing books.

Therefore, this site, Samland's Disney Adventures will be on hiatus. To find out if the status changes I suggest you join The Disneyland Story page and that is where I will post the latest updates. As for MiceChat, it won't be every week but when there is something to say.

Thank you

Sam Gennawey

Published on December 12, 2013 09:25

November 18, 2013

Hale's Tours and Scenes of the World

THE MOTION SIMULATOR RIDE

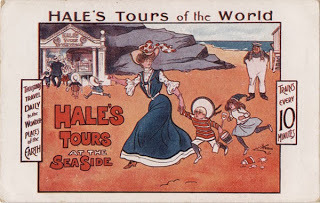

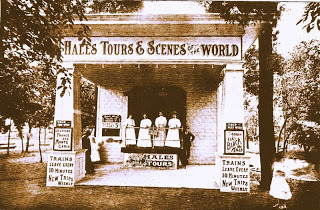

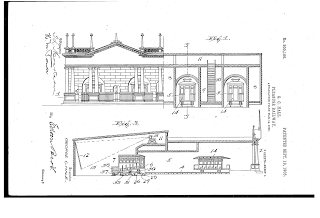

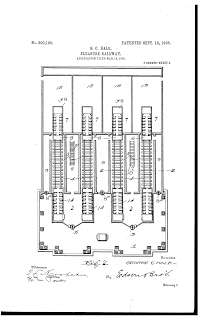

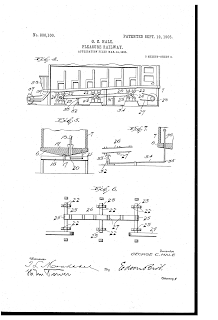

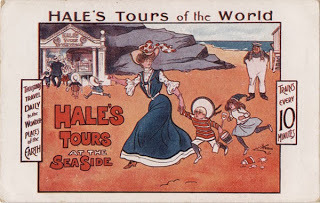

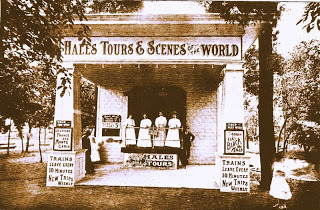

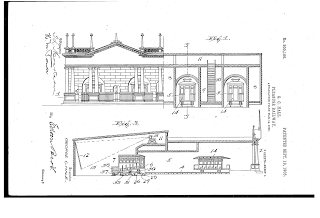

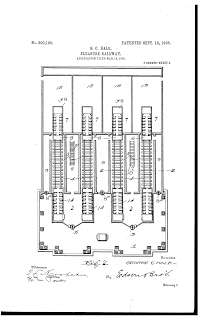

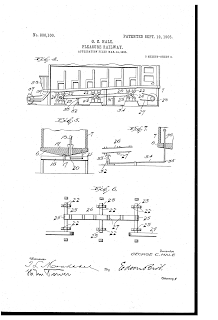

When Star Tours opened at Disneyland in 1987, little did the Imagineers know that they would create a new industry. The breakthrough attraction combined a motion simulation base with a film and a story to create an immersive environment that feels like you really are moving. It was not long before others would jump on the bandwagon and soon almost every shopping mall in America had such a device.But was Star Tours the first such ride? Step back to Kansas City in 1905 to Electric Park, an amusement park so amazing that it would become one of Walt Disney’s fondest childhood memories and an inspiration to Disneyland. One of the hit attractions was Hale’s Tours and Scenes of the World. George C. Hale, a retired fire chief, developed the attraction. The show was set in a railway car that seated seventy-two guests. At one end was a screen. Projected on the screen was a ten-minute film whose point of view was that of a camera mounted on the front of a moving train. This was known as a phantom ride. During the show, machines would rock the rail car from side to side, fans would blow, and painted scenery would pass by the windows. There was a special mechanism mounted on the undercarriage to recreate the clacking sound of the tracks. Whistles, bells, and live conductors added to the illusion. The show was very popular and the concept was licensed to others. By 1907 there were more than 500 Hale’s Tours worldwide. According to Historian Graeme Baker of Cineroama, “Hale’s Tours warmed up the public to moving pictures and demonstrated to venue owners that the market was prepared to bear the cost of higher ticket prices in return for theaters with themed entertainment spaces and quality interior and exterior design.”_ The Hale's Tours began to loose favor almost as fast as it began and by 1911 the last one shuttered its doors._Many Hollywood legends would have their first exposure to motion pictures by riding on the Hale’s Tour including Carl Laemmle (Universal), Mary Pickford (Actress and United Artists), Sam Warner (Warner Brothers), and Adolph Zukor (Paramount). The Hale's Tours began to loose favor almost as fast as the phenomena began and by 1911 the last one shuttered its doors.

The show was very popular and the concept was licensed to others. By 1907 there were more than 500 Hale’s Tours worldwide. According to Historian Graeme Baker of Cineroama, “Hale’s Tours warmed up the public to moving pictures and demonstrated to venue owners that the market was prepared to bear the cost of higher ticket prices in return for theaters with themed entertainment spaces and quality interior and exterior design.”_ The Hale's Tours began to loose favor almost as fast as it began and by 1911 the last one shuttered its doors._Many Hollywood legends would have their first exposure to motion pictures by riding on the Hale’s Tour including Carl Laemmle (Universal), Mary Pickford (Actress and United Artists), Sam Warner (Warner Brothers), and Adolph Zukor (Paramount). The Hale's Tours began to loose favor almost as fast as the phenomena began and by 1911 the last one shuttered its doors.

This was not the first time somebody tried creating a Motion simulator. In 1895, Robert Paul and novelist H.G. Wells patented a movie house that was designed like a spaceship, using still photos and movies. Wells wanted to simulate his science fiction book, The Time Machine. The ride was never built. Then a few years later a French company built the Cineorama, a simulated ride in a hot-air balloon with a 360-degree view. The ride burnt down after two days. Then came the Lumiere Brothers attempt with the Mareorama, which simulated the view from a ship’s bridge.

This was not the first time somebody tried creating a Motion simulator. In 1895, Robert Paul and novelist H.G. Wells patented a movie house that was designed like a spaceship, using still photos and movies. Wells wanted to simulate his science fiction book, The Time Machine. The ride was never built. Then a few years later a French company built the Cineorama, a simulated ride in a hot-air balloon with a 360-degree view. The ride burnt down after two days. Then came the Lumiere Brothers attempt with the Mareorama, which simulated the view from a ship’s bridge.

Later, Disneyland would get into the act. The most famous example was the Rocket to the Moon attraction. Lessor known was Space Station X-1. From The Disneyland Story: The Unofficial Guide: “At a time when the first satellite to orbit the Earth was still a couple of years away, Walt thought it would be fun to give guests a bird’s-eye view of the world from a “platform in space.” That was the concept behind Space Station X-1. Claude Coats and Peter Ellenshaw painted an aerial view of the United States based on the first photograph from space, which was taken on October 24, 1946, from an altitude of 65 miles. In this case, they moved the perspective up to 90 miles in space and painted the scene on a doughnut-shaped canvas. Guests stood along a railing and looked down at the painting. The lighting changed from daytime to nighttime, and the painting was illuminated in black light. The platform moved from the East to West Coast in 3 minutes.78 Over the years, the name would be changed to the Satellite View of America, but that was not enough to draw guests, and it closed on February 17, 1960.”

Later, Disneyland would get into the act. The most famous example was the Rocket to the Moon attraction. Lessor known was Space Station X-1. From The Disneyland Story: The Unofficial Guide: “At a time when the first satellite to orbit the Earth was still a couple of years away, Walt thought it would be fun to give guests a bird’s-eye view of the world from a “platform in space.” That was the concept behind Space Station X-1. Claude Coats and Peter Ellenshaw painted an aerial view of the United States based on the first photograph from space, which was taken on October 24, 1946, from an altitude of 65 miles. In this case, they moved the perspective up to 90 miles in space and painted the scene on a doughnut-shaped canvas. Guests stood along a railing and looked down at the painting. The lighting changed from daytime to nighttime, and the painting was illuminated in black light. The platform moved from the East to West Coast in 3 minutes.78 Over the years, the name would be changed to the Satellite View of America, but that was not enough to draw guests, and it closed on February 17, 1960.”

When Star Tours opened at Disneyland in 1987, little did the Imagineers know that they would create a new industry. The breakthrough attraction combined a motion simulation base with a film and a story to create an immersive environment that feels like you really are moving. It was not long before others would jump on the bandwagon and soon almost every shopping mall in America had such a device.But was Star Tours the first such ride? Step back to Kansas City in 1905 to Electric Park, an amusement park so amazing that it would become one of Walt Disney’s fondest childhood memories and an inspiration to Disneyland. One of the hit attractions was Hale’s Tours and Scenes of the World. George C. Hale, a retired fire chief, developed the attraction. The show was set in a railway car that seated seventy-two guests. At one end was a screen. Projected on the screen was a ten-minute film whose point of view was that of a camera mounted on the front of a moving train. This was known as a phantom ride. During the show, machines would rock the rail car from side to side, fans would blow, and painted scenery would pass by the windows. There was a special mechanism mounted on the undercarriage to recreate the clacking sound of the tracks. Whistles, bells, and live conductors added to the illusion.

The show was very popular and the concept was licensed to others. By 1907 there were more than 500 Hale’s Tours worldwide. According to Historian Graeme Baker of Cineroama, “Hale’s Tours warmed up the public to moving pictures and demonstrated to venue owners that the market was prepared to bear the cost of higher ticket prices in return for theaters with themed entertainment spaces and quality interior and exterior design.”_ The Hale's Tours began to loose favor almost as fast as it began and by 1911 the last one shuttered its doors._Many Hollywood legends would have their first exposure to motion pictures by riding on the Hale’s Tour including Carl Laemmle (Universal), Mary Pickford (Actress and United Artists), Sam Warner (Warner Brothers), and Adolph Zukor (Paramount). The Hale's Tours began to loose favor almost as fast as the phenomena began and by 1911 the last one shuttered its doors.

The show was very popular and the concept was licensed to others. By 1907 there were more than 500 Hale’s Tours worldwide. According to Historian Graeme Baker of Cineroama, “Hale’s Tours warmed up the public to moving pictures and demonstrated to venue owners that the market was prepared to bear the cost of higher ticket prices in return for theaters with themed entertainment spaces and quality interior and exterior design.”_ The Hale's Tours began to loose favor almost as fast as it began and by 1911 the last one shuttered its doors._Many Hollywood legends would have their first exposure to motion pictures by riding on the Hale’s Tour including Carl Laemmle (Universal), Mary Pickford (Actress and United Artists), Sam Warner (Warner Brothers), and Adolph Zukor (Paramount). The Hale's Tours began to loose favor almost as fast as the phenomena began and by 1911 the last one shuttered its doors.

This was not the first time somebody tried creating a Motion simulator. In 1895, Robert Paul and novelist H.G. Wells patented a movie house that was designed like a spaceship, using still photos and movies. Wells wanted to simulate his science fiction book, The Time Machine. The ride was never built. Then a few years later a French company built the Cineorama, a simulated ride in a hot-air balloon with a 360-degree view. The ride burnt down after two days. Then came the Lumiere Brothers attempt with the Mareorama, which simulated the view from a ship’s bridge.

This was not the first time somebody tried creating a Motion simulator. In 1895, Robert Paul and novelist H.G. Wells patented a movie house that was designed like a spaceship, using still photos and movies. Wells wanted to simulate his science fiction book, The Time Machine. The ride was never built. Then a few years later a French company built the Cineorama, a simulated ride in a hot-air balloon with a 360-degree view. The ride burnt down after two days. Then came the Lumiere Brothers attempt with the Mareorama, which simulated the view from a ship’s bridge.  Later, Disneyland would get into the act. The most famous example was the Rocket to the Moon attraction. Lessor known was Space Station X-1. From The Disneyland Story: The Unofficial Guide: “At a time when the first satellite to orbit the Earth was still a couple of years away, Walt thought it would be fun to give guests a bird’s-eye view of the world from a “platform in space.” That was the concept behind Space Station X-1. Claude Coats and Peter Ellenshaw painted an aerial view of the United States based on the first photograph from space, which was taken on October 24, 1946, from an altitude of 65 miles. In this case, they moved the perspective up to 90 miles in space and painted the scene on a doughnut-shaped canvas. Guests stood along a railing and looked down at the painting. The lighting changed from daytime to nighttime, and the painting was illuminated in black light. The platform moved from the East to West Coast in 3 minutes.78 Over the years, the name would be changed to the Satellite View of America, but that was not enough to draw guests, and it closed on February 17, 1960.”

Later, Disneyland would get into the act. The most famous example was the Rocket to the Moon attraction. Lessor known was Space Station X-1. From The Disneyland Story: The Unofficial Guide: “At a time when the first satellite to orbit the Earth was still a couple of years away, Walt thought it would be fun to give guests a bird’s-eye view of the world from a “platform in space.” That was the concept behind Space Station X-1. Claude Coats and Peter Ellenshaw painted an aerial view of the United States based on the first photograph from space, which was taken on October 24, 1946, from an altitude of 65 miles. In this case, they moved the perspective up to 90 miles in space and painted the scene on a doughnut-shaped canvas. Guests stood along a railing and looked down at the painting. The lighting changed from daytime to nighttime, and the painting was illuminated in black light. The platform moved from the East to West Coast in 3 minutes.78 Over the years, the name would be changed to the Satellite View of America, but that was not enough to draw guests, and it closed on February 17, 1960.”

Published on November 18, 2013 23:16

November 6, 2013

Universal Studio Tour Latest Attractions - 1974

In 1974, RockSlide became the latest filmmaking demonstration added to the Studio Tour. Based loosely on the hit film Earthquake, the tram would stop along a rocky hillside when suddenly the earth grumbles and styrofoam boulders rolled down toward the trams. The boulders would be gathered by a metal scoop bucket and then transported back up the hill and placed on a tilting platform. The scoop would then lower back to the bottom of the hill. The entire process was supposed to take 90 seconds. At least that was the idea. RockSlide never really worked. The scoop mechanism was very slow and was not able to keep pace with the trams. If the hillside was wet, the rocks absorbed the water and would spray the visitors as they slammed into the bottom of the hill. When the hillside was dry, the rocks would bounce into the trams and create havoc. A far more sophisticated and convincing display was the Collapsing Bridge. As the tram approached a dilapidated bridge, the tour guide suggested to the driver that they drive around it. However, the driver does not listen and took the guests over the bridge. When the tram reached the half-way point, the bridge began to creak and timbers started to fall away. All of a sudden, the deck of the bridge dropped a few inches, giving the visitors a scare. As the tram pulled away, visitors could see the bridge reset itself. The set was designed using a computer control system built by Antioch and hydraulic lifts like those found in an elevator.Another tour enhancement was The Runaway Train. Added in 1974, the tram would approach a railroad crossing and stop with the center car over the tracks. Suddenly, off in the distance a the loud chug of a steam train and its distinctive whistle could be heard. The wiggle waggle warning light next to the tram goes berserk. Then the visitors see it. Bearing down on the tram at seven miles per hours was a nine-ton locomotive. Fortunately, the train stops inches from the tram.

In 1974, RockSlide became the latest filmmaking demonstration added to the Studio Tour. Based loosely on the hit film Earthquake, the tram would stop along a rocky hillside when suddenly the earth grumbles and styrofoam boulders rolled down toward the trams. The boulders would be gathered by a metal scoop bucket and then transported back up the hill and placed on a tilting platform. The scoop would then lower back to the bottom of the hill. The entire process was supposed to take 90 seconds. At least that was the idea. RockSlide never really worked. The scoop mechanism was very slow and was not able to keep pace with the trams. If the hillside was wet, the rocks absorbed the water and would spray the visitors as they slammed into the bottom of the hill. When the hillside was dry, the rocks would bounce into the trams and create havoc. A far more sophisticated and convincing display was the Collapsing Bridge. As the tram approached a dilapidated bridge, the tour guide suggested to the driver that they drive around it. However, the driver does not listen and took the guests over the bridge. When the tram reached the half-way point, the bridge began to creak and timbers started to fall away. All of a sudden, the deck of the bridge dropped a few inches, giving the visitors a scare. As the tram pulled away, visitors could see the bridge reset itself. The set was designed using a computer control system built by Antioch and hydraulic lifts like those found in an elevator.Another tour enhancement was The Runaway Train. Added in 1974, the tram would approach a railroad crossing and stop with the center car over the tracks. Suddenly, off in the distance a the loud chug of a steam train and its distinctive whistle could be heard. The wiggle waggle warning light next to the tram goes berserk. Then the visitors see it. Bearing down on the tram at seven miles per hours was a nine-ton locomotive. Fortunately, the train stops inches from the tram. The effect took four months to build. The locomotive was powered by air motors with two braking systems. Like the Collapsing Bridge, visitors could see the show reset as they drove away. Behind them, the locomotive would quietly roll back to its hidden position. The gag could be repeated every two minutes. The new attractions helped to bring 1.816 million visitors to the Studio Tour in 1974.

Published on November 06, 2013 04:00

November 5, 2013

What Every Theme Park Needs - Space

One of the best features found at Universal's Islands of Adventures are the public areas that line the lagoon. No matter how busy the place is, you can always find a quiet spot to regroup, relax, make a phone call. I urge you to seek these spaces out.

Published on November 05, 2013 19:03

November 4, 2013

The New Mickey Mouse Cartoon Shorts

DISNEY MICKEY MOUSECartoon ShortsAvailable on iTunes and online

When it comes to showing my Disney Side (clever campaign) I tend to lean toward the theme parks. This means I am not usually a first adopter of a lot of products produced by the other divisions. However, there was one new cartoon series that I have been really looking forward to ever since I saw the preview in March 2013. Under the leadership of Executive Producer Paul Radish, Mickey Mouse has returned, scrubbed of the sanitized corporate symbol attitude, and returned to his roots as a blend of Charlie Chaplin, Errol Flynn, Walt Disney, and the Keystone Cops. Starting last summer, Disney began releasing 19 of these groundbreaking 3+ minute shorts. Gone is the bland, safe Mickey. Enter the Mickey that resembles the one that first captured the public’s attention in 1928. Set in contemporary times, Mickey and his friends are happy to break into a neighbors house to use his pool on a hot day, cheat in a dog show, and steal an ice cream truck. Creating chaos is a given in each episode and at times resembles the energy of a Tex Avery cartoon or one of the Roger Rabbit shorts. In the end, Mickey does save the day and everything turns out right. Just like the original early classic Mickey Mouse shorts, kids will love these but they really are written for adults.In the first episode, Croissant de Triomphe, Minnie runs out of croissants at her restaurant in Paris and calls out to Mickey (in French) to bring more. Mickey jets through the streets of Paris, close calls at every turn, as he tries to get to Minnie in time. The storyboard sessions must have been a blast because the gags that made it to the final cut will make you laugh out loud. It is both timeless and relevant at the same time. The animation is fresh, fluid, rubbery, and throughly 2D. I like this version of Mickey. That was just a start. In No Service we get to see a naked Mickey in a public place. In Yodelberg Mickey gets to meet a yeti and New York Weenie will make you look at hot dogs in a new way. Tokyo Go and Panda-monism show that Mickey is an international star and are set in Japan and China. We have all had a Bad Ear Day. Stayin’ Cool was released when Los Angeles was suffering from an unbearable heatwave and summed up that experience better then anything I have ever seen. Zombie Goofy. Gubbles. This will all make sense as you watch the series. Mickey is alive and well in the hands of this team of animators.

Published on November 04, 2013 06:00

October 28, 2013

A History of Twister: Ride It Out at Universal Studios Florida

Universal executives were always on the hunt for intellectual properties or technologies that they could exploit. Any film with a clear vision and extensive special effects was game. Amblin Entertainment’s Twister (1996) seemed like a perfect fit. The special effects loaded film was based on the adventures of scientists who chase after tornados. Bringing a tornado indoors and repeating the show dozens of times a day would be an impressive feat of engineering. The project was inspired by a sculpture from artist Ned Kahn who specialized in sculpting tornadoes and vortexes with installations in science centers around the world. A Universal executive saw one of his pieces that generated a vortex in San Francisco and realized that the illusion looked like a small tornado. The team at Universal Creative began work on creating a larger vortex and hired wind-flow experts Cermak Peterka Petersen, Inc. The firm had worked on more than 2,000 projects including the World Trade Towers in New York. The goal was to create a reliable indoor tornado that was approximately five stories tall and twelve feet wide. If successful they would have built the largest indoor tornado ever created by man. They began by building a one-fourth scale model of the vortex, which worked beautifully. Feeling confident, the model was scaled up to full size. That is when the problems started. To generate the full size effect, it was necessary to generate constant winds of 35 miles per hour. A studio was outfitted with thirty specially designed fans arranged in three tiers; ground level, mid level, and high level. Eighteen of those fans had blades seven feet tall. “We invited our employees into the ride," said J. Michael Hightower, the project director. "It had a detrimental effect on the tornado. This special effect is the most difficult at Universal because we don’t have direct control over it. For instance, if we want the Jaws shark to move faster, we just turn up the pressure.” A computerized weather tracking system was installed that monitored the outside wind velocity, humidity and barometric pressure to maximize the size and shape of the twister inside. They brought in 240 mannequins with clothes to tweak the effect. The result was a reliable tornado of the correct size that could move as much as thirty feet in any direction from its origin. The volume of air used could fill four full-size airborne blimps. Spending the project budget on spectacular, memorable special effects instead of a ride mechanism made financial sense. Plus, the box-office success of the film, therefore it’s visibility, was high on the priority list for both Warner Bros. and Universal who jointly produced the film. When the $16 million Twister: Ride It Out opened on May 4, 1997, it represented a new level of sophistication in special effects demonstrations. Like the other special effects demonstrations, the show was broken into three acts each in a different setting. The first act was a preshow that included an audio-visual presentation. The second room resembled a tornado damaged building. The two stars of the film, Bill Paxton and Helen Hunt, were filmed separately for their introductions and shown on two separate screens because of reports that they did not like each other. The final act took place inside of a 25,000 square foot soundstage on a set that resembled an outdoor scene. Visitors filed on to a elevated viewing platform and come face to face with more than fifty-five special effects. Hundreds of xenon strobes flash, simulating lightning. The sound of thunder was piped through fifty-four speakers powered by 42,000 watts, enough to power five average homes. The roar of the hurricane was made of a combination of sounds including camel sounds, lion roars, and backward human and animal screams. More than 65,000 gallons of recycled water fed the rainstorm and could be ready for the next show every six minutes. The twenty laser disc players, three-hundred speakers, and sixty video monitors were connected by fifty miles of electrical wire, and controlled by twenty computers. One of the most memorable effects from both the movie and the show was a flying cow.

Universal executives were always on the hunt for intellectual properties or technologies that they could exploit. Any film with a clear vision and extensive special effects was game. Amblin Entertainment’s Twister (1996) seemed like a perfect fit. The special effects loaded film was based on the adventures of scientists who chase after tornados. Bringing a tornado indoors and repeating the show dozens of times a day would be an impressive feat of engineering. The project was inspired by a sculpture from artist Ned Kahn who specialized in sculpting tornadoes and vortexes with installations in science centers around the world. A Universal executive saw one of his pieces that generated a vortex in San Francisco and realized that the illusion looked like a small tornado. The team at Universal Creative began work on creating a larger vortex and hired wind-flow experts Cermak Peterka Petersen, Inc. The firm had worked on more than 2,000 projects including the World Trade Towers in New York. The goal was to create a reliable indoor tornado that was approximately five stories tall and twelve feet wide. If successful they would have built the largest indoor tornado ever created by man. They began by building a one-fourth scale model of the vortex, which worked beautifully. Feeling confident, the model was scaled up to full size. That is when the problems started. To generate the full size effect, it was necessary to generate constant winds of 35 miles per hour. A studio was outfitted with thirty specially designed fans arranged in three tiers; ground level, mid level, and high level. Eighteen of those fans had blades seven feet tall. “We invited our employees into the ride," said J. Michael Hightower, the project director. "It had a detrimental effect on the tornado. This special effect is the most difficult at Universal because we don’t have direct control over it. For instance, if we want the Jaws shark to move faster, we just turn up the pressure.” A computerized weather tracking system was installed that monitored the outside wind velocity, humidity and barometric pressure to maximize the size and shape of the twister inside. They brought in 240 mannequins with clothes to tweak the effect. The result was a reliable tornado of the correct size that could move as much as thirty feet in any direction from its origin. The volume of air used could fill four full-size airborne blimps. Spending the project budget on spectacular, memorable special effects instead of a ride mechanism made financial sense. Plus, the box-office success of the film, therefore it’s visibility, was high on the priority list for both Warner Bros. and Universal who jointly produced the film. When the $16 million Twister: Ride It Out opened on May 4, 1997, it represented a new level of sophistication in special effects demonstrations. Like the other special effects demonstrations, the show was broken into three acts each in a different setting. The first act was a preshow that included an audio-visual presentation. The second room resembled a tornado damaged building. The two stars of the film, Bill Paxton and Helen Hunt, were filmed separately for their introductions and shown on two separate screens because of reports that they did not like each other. The final act took place inside of a 25,000 square foot soundstage on a set that resembled an outdoor scene. Visitors filed on to a elevated viewing platform and come face to face with more than fifty-five special effects. Hundreds of xenon strobes flash, simulating lightning. The sound of thunder was piped through fifty-four speakers powered by 42,000 watts, enough to power five average homes. The roar of the hurricane was made of a combination of sounds including camel sounds, lion roars, and backward human and animal screams. More than 65,000 gallons of recycled water fed the rainstorm and could be ready for the next show every six minutes. The twenty laser disc players, three-hundred speakers, and sixty video monitors were connected by fifty miles of electrical wire, and controlled by twenty computers. One of the most memorable effects from both the movie and the show was a flying cow. The show replaced the Ghostbusters Spectacular in the New York zone. The grand opening was originally scheduled to open in April 1997 but was delayed one month due to tornados that killed forty-two people in Central Florida in February of that year. Universal donated $100,000 to aid the victims. Shortly after the opening, Reel EFX, Inc. sued Universal over the faux weather effect technology used in the Twister attraction.

Published on October 28, 2013 06:00

October 25, 2013

The Quality Without a Name

The only way to build beautiful and functional public spaces is to learn the code that unlocks the riddle: how do such places happen? We have all experienced environments that exhibit the timeless way of building. Alexander said these places reveal “the quality without a name.” Think back to a place where everything seems just right. You cannot quite put your finger on it, it is hard to explain to somebody else, and your words will always seem inadequate—but there is something there that transcends other places you have experienced. Alexander suggested, “There is a central quality, which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building or a wilderness. This quality is objective and precise, but it cannot be named.”Why does this matter? When you consider that there are billions of people in the world, the challenge that the Imagineers had to create spaces that appeal to such a broad range of opinions and cultures would seem insurmountable. However, Walt and his design team understood what Alexander meant, and they achieved this “quality without a name”—the quality that appeals universally to all people—in many parts of Disneyland. Surely this is one of the reasons for the park’s tremendous success and why guests keep coming back. Had he lived to build his other environmental design projects, Walt would have infused them with the same quality. “Success is doing ordinary things extraordinarily well,” according to business philosopher Jim Rohn; this was one of Walt’s greatest strengths.Walt was not the first person to produce animated films, but he elevated the art form to a level that has yet to be topped. In Designing Disney’s Theme Parks, cultural historian Karal Ann Marling said, “The painstaking art of animation was, after all, the art of perfecting the world. It was a world over which Walt Disney exercised total, beneficent control.” Walt wanted to have the same impact on the art of three-dimensional spatial design with the opening of Disneyland. Millions of visitors come to the Disney theme parks to experience the Disney “magic.” So what exactly are they looking for? In Disneywar, James B. Stewart defined the Disney magic as that moment when “people’s apprehension turns into awe and delight.” When Disney guests step into the environment based on a timeless way of building—an environment that has the quality without a name—they realize that they are in a place where their dreams can come true.Perhaps you have witnessed how a carefully designed, immersive environment can make a significant impression on the individual and can quickly change one’s mood and behavior. Walt had the vision and desire to create such a place. As a result, he changed the way we look at the public realm. How did he do this? Why are some places filled with life while other places seem so lifeless?Christopher Alexander suggested that “What we call ‘life’ is a general condition, which exists, to some degree or other, in every part of space: brick, stone, grass, river, painting, building, daffodil, human being, forest, city.” Alexander added, “The key to this idea is that every part of space—every connected region of space, small or large—has some degree of life.” Most importantly, “This degree of life is well defined, objectively existing, and measurable.” A space that demonstrates a high-quality, positive experience for the majority of people is one that has a “higher degree of life.” Understanding what these measurable qualities are can help to unlock the riddle of how to create wonderful places.Many urban planners and architects find it important to be able to measure how successful a space or structure is. Alexander tried to be more precise by saying, “We are going to pay attention to what we can see and what we can identify and what we can know.” That is the start. It is also important that the knowledge be shared, that it be “put in some kind of experimental form, that another person can then be convinced of.” Architect Matthew Frederick provided one definition for sharable knowledge. He suggested, “If you can’t explain your ideas to your grandmother in terms that she understands, you don’t know your subject well enough.”

The only way to build beautiful and functional public spaces is to learn the code that unlocks the riddle: how do such places happen? We have all experienced environments that exhibit the timeless way of building. Alexander said these places reveal “the quality without a name.” Think back to a place where everything seems just right. You cannot quite put your finger on it, it is hard to explain to somebody else, and your words will always seem inadequate—but there is something there that transcends other places you have experienced. Alexander suggested, “There is a central quality, which is the root criterion of life and spirit in a man, a town, a building or a wilderness. This quality is objective and precise, but it cannot be named.”Why does this matter? When you consider that there are billions of people in the world, the challenge that the Imagineers had to create spaces that appeal to such a broad range of opinions and cultures would seem insurmountable. However, Walt and his design team understood what Alexander meant, and they achieved this “quality without a name”—the quality that appeals universally to all people—in many parts of Disneyland. Surely this is one of the reasons for the park’s tremendous success and why guests keep coming back. Had he lived to build his other environmental design projects, Walt would have infused them with the same quality. “Success is doing ordinary things extraordinarily well,” according to business philosopher Jim Rohn; this was one of Walt’s greatest strengths.Walt was not the first person to produce animated films, but he elevated the art form to a level that has yet to be topped. In Designing Disney’s Theme Parks, cultural historian Karal Ann Marling said, “The painstaking art of animation was, after all, the art of perfecting the world. It was a world over which Walt Disney exercised total, beneficent control.” Walt wanted to have the same impact on the art of three-dimensional spatial design with the opening of Disneyland. Millions of visitors come to the Disney theme parks to experience the Disney “magic.” So what exactly are they looking for? In Disneywar, James B. Stewart defined the Disney magic as that moment when “people’s apprehension turns into awe and delight.” When Disney guests step into the environment based on a timeless way of building—an environment that has the quality without a name—they realize that they are in a place where their dreams can come true.Perhaps you have witnessed how a carefully designed, immersive environment can make a significant impression on the individual and can quickly change one’s mood and behavior. Walt had the vision and desire to create such a place. As a result, he changed the way we look at the public realm. How did he do this? Why are some places filled with life while other places seem so lifeless?Christopher Alexander suggested that “What we call ‘life’ is a general condition, which exists, to some degree or other, in every part of space: brick, stone, grass, river, painting, building, daffodil, human being, forest, city.” Alexander added, “The key to this idea is that every part of space—every connected region of space, small or large—has some degree of life.” Most importantly, “This degree of life is well defined, objectively existing, and measurable.” A space that demonstrates a high-quality, positive experience for the majority of people is one that has a “higher degree of life.” Understanding what these measurable qualities are can help to unlock the riddle of how to create wonderful places.Many urban planners and architects find it important to be able to measure how successful a space or structure is. Alexander tried to be more precise by saying, “We are going to pay attention to what we can see and what we can identify and what we can know.” That is the start. It is also important that the knowledge be shared, that it be “put in some kind of experimental form, that another person can then be convinced of.” Architect Matthew Frederick provided one definition for sharable knowledge. He suggested, “If you can’t explain your ideas to your grandmother in terms that she understands, you don’t know your subject well enough.”If you are a city planner and see your role as a resource management expert, then the solution is to demand that everything be measurable. So how do you measure something as seemingly intangible as a “higher degree of life”? How do you describe that quality in a way everybody can understand?

Published on October 25, 2013 06:00

October 21, 2013

You Can���t Top Pigs with Pigs

After a tough opening day and some negative reviews, Disneyland turned out to be a smash hit when it opened in 1955. The park turned sleepy Anaheim into one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States. The economic windfall to Orange County was unimaginable. It seemed that every city in America wanted a Disneyland.There was only one problem. Over the years, it became a well- known fact that Walt Disney did not like to do the same thing twice. He said, ���I���ve never believed in doing sequels. I didn���t want to waste the time I have doing a sequel. I���d rather be using that time doing something new and different.��� He liked new challenges and he already had a Disneyland. What was the point of building another theme park?Walt said, ���It goes back when they wanted me to do more pigs.��� The Silly Symphony cartoon Three Little Pigs became a huge success in 1933 due in part to Who���s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf, a hit song that resonated with Great Depression audiences. Theater owners were clamoring for a follow-up. Walt hesitated. He proclaimed, ���You can���t top pigs with pigs.���Nevertheless, Walt could be practical when necessary, and he had ambitious plans for the animation studio. Those ambitions cost a lot of money. Therefore, he relented and produced two follow-up cartoon shorts. Unfortunately, Walt was right���the follow-up films did not have nearly the impact or commercial success as the original.

After a tough opening day and some negative reviews, Disneyland turned out to be a smash hit when it opened in 1955. The park turned sleepy Anaheim into one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States. The economic windfall to Orange County was unimaginable. It seemed that every city in America wanted a Disneyland.There was only one problem. Over the years, it became a well- known fact that Walt Disney did not like to do the same thing twice. He said, ���I���ve never believed in doing sequels. I didn���t want to waste the time I have doing a sequel. I���d rather be using that time doing something new and different.��� He liked new challenges and he already had a Disneyland. What was the point of building another theme park?Walt said, ���It goes back when they wanted me to do more pigs.��� The Silly Symphony cartoon Three Little Pigs became a huge success in 1933 due in part to Who���s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf, a hit song that resonated with Great Depression audiences. Theater owners were clamoring for a follow-up. Walt hesitated. He proclaimed, ���You can���t top pigs with pigs.���Nevertheless, Walt could be practical when necessary, and he had ambitious plans for the animation studio. Those ambitions cost a lot of money. Therefore, he relented and produced two follow-up cartoon shorts. Unfortunately, Walt was right���the follow-up films did not have nearly the impact or commercial success as the original.In 1959, twenty-six years later, Walt found himself in a similar dilemma. With an opportunity in Palm Beach before him, he saw that it would be possible to design a new town where people could live, work, and play. His city would function as well as Disneyland and his Burbank studio. It would be a suitable neighbor for his theme park. More importantly, this would not be a sequel.

Published on October 21, 2013 06:00

You Can’t Top Pigs with Pigs

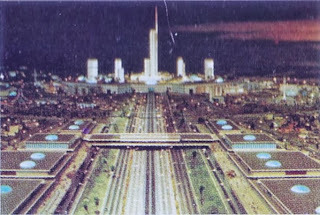

After a tough opening day and some negative reviews, Disneyland turned out to be a smash hit when it opened in 1955. The park turned sleepy Anaheim into one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States. The economic windfall to Orange County was unimaginable. It seemed that every city in America wanted a Disneyland.There was only one problem. Over the years, it became a well- known fact that Walt Disney did not like to do the same thing twice. He said, “I’ve never believed in doing sequels. I didn’t want to waste the time I have doing a sequel. I’d rather be using that time doing something new and different.” He liked new challenges and he already had a Disneyland. What was the point of building another theme park?Walt said, “It goes back when they wanted me to do more pigs.” The Silly Symphony cartoon Three Little Pigs became a huge success in 1933 due in part to Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf, a hit song that resonated with Great Depression audiences. Theater owners were clamoring for a follow-up. Walt hesitated. He proclaimed, “You can’t top pigs with pigs.”Nevertheless, Walt could be practical when necessary, and he had ambitious plans for the animation studio. Those ambitions cost a lot of money. Therefore, he relented and produced two follow-up cartoon shorts. Unfortunately, Walt was right—the follow-up films did not have nearly the impact or commercial success as the original.

After a tough opening day and some negative reviews, Disneyland turned out to be a smash hit when it opened in 1955. The park turned sleepy Anaheim into one of the fastest-growing cities in the United States. The economic windfall to Orange County was unimaginable. It seemed that every city in America wanted a Disneyland.There was only one problem. Over the years, it became a well- known fact that Walt Disney did not like to do the same thing twice. He said, “I’ve never believed in doing sequels. I didn’t want to waste the time I have doing a sequel. I’d rather be using that time doing something new and different.” He liked new challenges and he already had a Disneyland. What was the point of building another theme park?Walt said, “It goes back when they wanted me to do more pigs.” The Silly Symphony cartoon Three Little Pigs became a huge success in 1933 due in part to Who’s Afraid of the Big Bad Wolf, a hit song that resonated with Great Depression audiences. Theater owners were clamoring for a follow-up. Walt hesitated. He proclaimed, “You can’t top pigs with pigs.”Nevertheless, Walt could be practical when necessary, and he had ambitious plans for the animation studio. Those ambitions cost a lot of money. Therefore, he relented and produced two follow-up cartoon shorts. Unfortunately, Walt was right—the follow-up films did not have nearly the impact or commercial success as the original.In 1959, twenty-six years later, Walt found himself in a similar dilemma. With an opportunity in Palm Beach before him, he saw that it would be possible to design a new town where people could live, work, and play. His city would function as well as Disneyland and his Burbank studio. It would be a suitable neighbor for his theme park. More importantly, this would not be a sequel.

Published on October 21, 2013 06:00