S.B. Stewart-Laing's Blog, page 24

March 20, 2013

Making the Most of Critiques, Part II

Now that you've collected your feedback, it's time to incorporate this into your edits. Assuming you didn't solicit all your critiques from identical robots, you'll have some comments which contradict each other, some that don't make sense, some that make you squirm, and some that just make you mad. Trying to follow up on everything that any of your readers has said is a recipe for revision stalemate and lots of frustration. Instead, it helps to do a bit of advice culling.

Now that you've collected your feedback, it's time to incorporate this into your edits. Assuming you didn't solicit all your critiques from identical robots, you'll have some comments which contradict each other, some that don't make sense, some that make you squirm, and some that just make you mad. Trying to follow up on everything that any of your readers has said is a recipe for revision stalemate and lots of frustration. Instead, it helps to do a bit of advice culling.Throw out the weird stuff. If you're getting critiques from the wilderness that is the internet, there will be some. This means the conspiracy theories, political rants, comparisons to random things (yes, Mike and I got all of the above!) get the delete key. The ones that make you mad usually fall into this category. Tally it up. If one person notices something, it may or may not be important (see below). If a bakers' dozen of people make variations on the same comment-- positive or negative-- they are very likely onto something. You cannot please everyone, and in this case, you want to tap into the wisdom of the average reader. For example, Michael and I originally included a good deal of dialogue in Scots, and used modern orthography. The general feedback was that it confounded and annoyed most English speakers (sorry guys!), so we compromised and rendered the dialogue in Scots-influenced English. Note what hits a nerve. If a comment stings, it may well reflect a conscious or subconscious worry you have about the story. Dig in and see if the commenter has a point. If you like, take a step back and 'cool off', which may allow you to look at the feedback with a clearer head. You're the boss! Remember, feedback is great, and can point you in the right direction when you're improving your work. However, you make the ultimate decisions about your story, and you get to decide whether to act on the critiques you collect, and how much.

Published on March 20, 2013 07:22

March 18, 2013

Making the Most of Critiques, Part I

One of the most important parts of the writing process is collecting audience feedback. We all need objective eyes to evaluate our work and help us improve. However, not all criticism is created equal. The first step in getting useful feedback is to solicit it correctly.

One of the most important parts of the writing process is collecting audience feedback. We all need objective eyes to evaluate our work and help us improve. However, not all criticism is created equal. The first step in getting useful feedback is to solicit it correctly. In this case, I'm a big fan of collecting a large sample. Art and entertainment are very subjective areas, and one person's favourite novel may be something their best friend finds gag-inducing. Furthermore, some people just have unusual tastes or perspectives, and probably won't give you an idea of what the 'average reader' thinks.

Ideally, you want to find fans of your genre. First, they can spot worn-out genre tropes right away. Second, it eliminates unhelpful feedback from people who dislike a genre on sight-- for example, Michael and I Third, these people most likely represent a sample of your real audience.

Finally, it's a good idea to flag up potentially controversial or triggering material in your book before you ask people to trade critiques. And while I'm a big fan of speaking up for one's beliefs, this is not the time and place to make a fuss about the person who doesn't want to read your story because they disagree with you. (For example, someone declined to read Forgotten Gods because of 'gay content'). Pressing the issue just leads to a lose-lose situation.

If you're intimidated by the idea of finding people to critique your work, try a site such as Authonomy, which encourages authors to review each other's works in progress. It can be a bit awkward at first, but getting a large amount of reader feedback at various writing stages is incredibly worthwhile.

Published on March 18, 2013 03:16

March 15, 2013

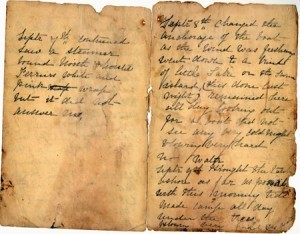

Reading Primary Sources

I love reading primary sources.

I love reading primary sources.It turns my endeavor of collecting facts about a historical period into an act of intimately studying the lives of people-- their attitudes, assumptions, daily struggles, and most cherished goals. However, it's also important to remember that these sources are direct reflections of their environment, and as such, fall onto the spectrum of unreliable narration.

Here are my favourite tips on how to put your sources in context in order to get the most-- and the most useful-- information you can from them:

Consider the writer. Each of us have unique life stories, but for some reason we seem to assume that people from the past are generic and interchangable. Find out what you can about the writer-- where were they from, what was their social standing, how old were they when they wrote the piece? Did they have any strong political motives?Consider prevailing attitudes. Some abolitionist literature from the 1700s and 1800s is shockingly racist by modern standards*. But compared to more typical attitudes of the time, these sources show progressive views. It's most informative to look at sources by comparing them to contemporary thought than to look at them through a modern lens. Look at background information. Knowing the general environment can help you understand not only references in the images or text, but the events leading up to whatever your sources are recording. This can shape how people reacted to or evaluated events-- records made in an era of unrest and paranoia will have different tone and content than those recorded in a stable environment. Avoid the Historian's Fallacy: Your source had zero knowledge of the future. This sounds obvious, but it's tempting to view the actions of historical figures in light of the outcome, rather than looking at their choices and views in the context of what knowledge they had available.

Primary sources are great fun, and hopefully any of you writing historical fiction (or using historical periods as a reference for your imagined worlds) will have fun with them.

*This isn't an attempt to excuse racist (or sexist, etc) material, but to explain it and place it in an appropriate perspective.

Published on March 15, 2013 03:04

March 13, 2013

Monolithic Political Groups

There are a lot of weirdly homogeneous groups in Fantasyland, particularly when they're united by a political cause. This is nothing like real life, so it's rather disconcerting to readers. Plus, you're passing up an excellent opportunity for increasing the complexity and intensity of conflict, and as a writer you should seek to sow chaos in your fictional worlds as much as you can.

There are a lot of weirdly homogeneous groups in Fantasyland, particularly when they're united by a political cause. This is nothing like real life, so it's rather disconcerting to readers. Plus, you're passing up an excellent opportunity for increasing the complexity and intensity of conflict, and as a writer you should seek to sow chaos in your fictional worlds as much as you can.In real life, the more a group is united around a single abstract goal, the more opportunity there is for conflict. First, people can be split over how to best achieve the changes they want. Second, although people may agree on one point, they can be a wildly diverse group otherwise. There can be clashing ideologies, clashing personalities, cross-cultural communication breakdowns and the like. Third, there can be a dispute over what the details that final goal actually are.

Besides that, people join political causes for different reasons. I remember going to a Young Democrats* meeting as a wee first-year undergrad in which we went around the room and said why we were there. Reasons included family voting traditions ('we've always voted Democrat'), obsession with single issues (the terrifying 'pro-choice' clique), peer pressure (this was why Yours Truly turned up), well-thought-out party allegiance (a dude who worked for Hilary Clinton over the summer), sheep mentality, and some mildly tipsy guys who wandered in to eat the free pizza. And that's just a small group. Expand this concept to a political movement, and you have a whole spectrum of participants. So if a political conflict is a central part of your story, your characters should have a range of commitment levels (from the fanatics to the 'free pizza' folks) and a variety of reasons for joining the cause.

*In all fairness, the Young Republicans were there because of family tradition, single-issue obsessions (the scary gun clique), defiance of peer pressure, well-thought-out party allegiance, religious beliefs, several drunks wanting free hot wings, and the need to get away from the overwhelming homogeneity of the Young Democrats.

Published on March 13, 2013 03:39

March 11, 2013

Sexual Hangups (Mildly NSFW)

There's lots of people in this world with some sexual neurosis or another. It could be from culturally-mediated weirdness, or a traumatic experience, or some other psychological issue. However, a lot of characters in Fantasyland (which is, for the most part, conspicuously lacking in sex therapists and couple's counseling) seem to get over their serious issues after one good roll in the hay with their True Love, at which point the problem is never mentioned again.

There's lots of people in this world with some sexual neurosis or another. It could be from culturally-mediated weirdness, or a traumatic experience, or some other psychological issue. However, a lot of characters in Fantasyland (which is, for the most part, conspicuously lacking in sex therapists and couple's counseling) seem to get over their serious issues after one good roll in the hay with their True Love, at which point the problem is never mentioned again.My first suggestion is that if you're don't want to write about the healing process, either make the character's sexual hangup permanent for the duration of the story, or forgo giving them one in the first place. If you're writing a female protagonist, please do consider option B. There's a troubling tendency to use rape in various manifestations as a shortcut to make a female lead 'darker and edgier', and it's gotten to the point of trivialising a major real-life issue as well as well as having a truckload of unfortunate implications about the female character.

Secondly, do some research if you want to go ahead with giving a character some sort of sexual issues. And their healing process will be shaped by the nature of the problem as well as their interactions in the story. Give them time to explore themselves and allow for the typical setbacks which accompany any attempts at personal growth. It will make for more interesting character development, and create a natural subplot.

Again, if you're not comfortable writing a character with sex-related issues, there's no rule saying you have to go there. You have infinite other options for tormenting your characters, and you can use those instead.

Published on March 11, 2013 03:41

March 8, 2013

Writing Spoiled Characters

'As I stood in my lonely bedroom at the hotel, trying to tie my white tie myself, it struck me for the first time that there must be whole squads of chappies in the world who had to get along without a man to look after them. I'd always thought of Jeeves as a kind of natural phenomenon; but, by Jove! of course, when you come to think of it, there must be quite a lot of fellows who have to press their own clothes themselves and haven't got anybody to bring them tea in the morning, and so on. It was rather a solemn thought, don't you know. I mean to say, ever since then I've been able to appreciate the frightful privations the poor have to stick.'--P.G. Wodehouse, My Man Jeeves

'As I stood in my lonely bedroom at the hotel, trying to tie my white tie myself, it struck me for the first time that there must be whole squads of chappies in the world who had to get along without a man to look after them. I'd always thought of Jeeves as a kind of natural phenomenon; but, by Jove! of course, when you come to think of it, there must be quite a lot of fellows who have to press their own clothes themselves and haven't got anybody to bring them tea in the morning, and so on. It was rather a solemn thought, don't you know. I mean to say, ever since then I've been able to appreciate the frightful privations the poor have to stick.'--P.G. Wodehouse, My Man JeevesFiction is full of characters who are somewhere on the spectrum of spoiled. For the purposes of this post, it's a character who combines access to social perks and Nice Things with the attitude that they're entitled to those goodies and a complete disregard for the have-nots around them.

That said, there are a lot of spoiled characters in fiction who inhabit the annoying brat zone when the author intends them to be a sympathetic-- or even heroic-- protagonist. Usually it's because the author ignored a simple rule: that there exists a strong inverse relationship between how nice the character in question is, and how long the story can go before whacking them with a clue-by-four. I chose Bertie Wooster for the page quote because he embodies a character who can be utterly clueless about his own privilege, and yet be liked by the audience. Frances Hodgson Burnett took the inverse approach in The Secret Garden, and wrote the protagonist, Mary, as a mean, bratty character who is hit head-on by reality in the first chapter, and is forced to go through major character development from the get-go.Another piece of the puzzle is awareness. As I mentioned when talking about characters with offensive views, a behaviour is more forgivable when one sees how it was shaped by the environment. Someone who truly doesn't have a sense of actual deprivation comes off better than someone who knows what the less fortunate are going through and doesn't care.

Published on March 08, 2013 02:33

March 6, 2013

Guest Post: Writing Disability, Part II

Hello again! Katherine Duke here. In this second installment, I’ll give a few general suggestions for crafting believable and compelling characters with disabilities (CWDs):

1. Research the disability. Before you explicitly establish that a character has a particular real physiological or psychological condition, it’s just common sense to read up on the condition. Perhaps talk with people who have it. If you can write from your own personal experience, so much the better! Learn about the condition’s causes, symptoms, and treatments. Does it tend to coincide with other conditions? Does it have a genetic component, such that it might run in your CWD’s family? Does it get more or less severe with time? What assistive devices or services might be available—or just out of reach—for someone in your CWD’s historical and socioeconomic circumstances? Your CWD need not be a cut-and-dried textbook case, but if you want to take lots of liberties with the symptoms, you might be better off just making up a fictional condition.

2. Think carefully about when and how your CWD acquired the disability, and how this might affect the way he lives with it. If, say, a head injury or a magical spell suddenly robbed him of his sight just yesterday, he’ll probably be clumsy and frustrated—and scared that he’ll always be that way. If he’s lost his vision gradually over many years, he may now be quite skilled at hiding or compensating for the impairment. If he was born without vision, his blindness might be a fully integrated, comfortable part of his identity.3. Consider that disability is context-dependent. In one physical, social, or technological environment, a CWD’s condition might put her at a devastating disadvantage. But in another, the same condition might be no more than a minor inconvenience—it might even give the character an edge. The CWD will likely seek out and create environments wherein it’s easiest for her to get what she wants and needs. But you might want to crank up the struggle and suspense by occasionally leading the CWD into more difficult milieus. 4. Think about the options the disability opens up for the CWD, not just those it closes off. Maybe an unlucky camper can free himself from a bear trap by detaching his prosthetic leg (and his next challenge is to hop or crawl all the way through the forest to safety). Maybe a mischievous little girl can earn extra pocket money by charging her friends for rides in her electric wheelchair. Maybe two deaf characters can sign to one another without the hearing characters suspecting that they’re plotting something. In short: instead of regarding the disability solely as a hindrance or a lack, try sometimes thinking of it as a set of accessories that are potentially useful, to the character(s) and to you as the writer. There is, of course, no single character or story that can perfectly represent the entire phenomenon of disability. The best we can try for is an ever-wider variety of thoughtfully developed portrayals that continue to surprise our audiences.

1. Research the disability. Before you explicitly establish that a character has a particular real physiological or psychological condition, it’s just common sense to read up on the condition. Perhaps talk with people who have it. If you can write from your own personal experience, so much the better! Learn about the condition’s causes, symptoms, and treatments. Does it tend to coincide with other conditions? Does it have a genetic component, such that it might run in your CWD’s family? Does it get more or less severe with time? What assistive devices or services might be available—or just out of reach—for someone in your CWD’s historical and socioeconomic circumstances? Your CWD need not be a cut-and-dried textbook case, but if you want to take lots of liberties with the symptoms, you might be better off just making up a fictional condition.

2. Think carefully about when and how your CWD acquired the disability, and how this might affect the way he lives with it. If, say, a head injury or a magical spell suddenly robbed him of his sight just yesterday, he’ll probably be clumsy and frustrated—and scared that he’ll always be that way. If he’s lost his vision gradually over many years, he may now be quite skilled at hiding or compensating for the impairment. If he was born without vision, his blindness might be a fully integrated, comfortable part of his identity.3. Consider that disability is context-dependent. In one physical, social, or technological environment, a CWD’s condition might put her at a devastating disadvantage. But in another, the same condition might be no more than a minor inconvenience—it might even give the character an edge. The CWD will likely seek out and create environments wherein it’s easiest for her to get what she wants and needs. But you might want to crank up the struggle and suspense by occasionally leading the CWD into more difficult milieus. 4. Think about the options the disability opens up for the CWD, not just those it closes off. Maybe an unlucky camper can free himself from a bear trap by detaching his prosthetic leg (and his next challenge is to hop or crawl all the way through the forest to safety). Maybe a mischievous little girl can earn extra pocket money by charging her friends for rides in her electric wheelchair. Maybe two deaf characters can sign to one another without the hearing characters suspecting that they’re plotting something. In short: instead of regarding the disability solely as a hindrance or a lack, try sometimes thinking of it as a set of accessories that are potentially useful, to the character(s) and to you as the writer. There is, of course, no single character or story that can perfectly represent the entire phenomenon of disability. The best we can try for is an ever-wider variety of thoughtfully developed portrayals that continue to surprise our audiences.

Published on March 06, 2013 02:30

March 4, 2013

Guest Post: Writing Disability, Part I

Please welcome our lovely guest poster (and fellow Amherst College alum), non-fiction writer and editor Kat Duke! You can find her blog here, or follow her on Twitter here.

I’m Katherine Duke. I grew up writing fiction, I hold bachelor’s and master’s degrees in creative writing, and I earn my living as a nonfiction writer and editor. I’m also a life-long wheelchair user, and I’m working on a nonfiction book about the social, romantic, and sexual lives of real-life people with disabilities (let’s call us RLPWDs). So the creators of this blog invited me to write about the portrayal of fictional characters with disabilities (CWDs).

I, for one, would like to see disability show up more frequently in fiction—not just because it directly and indirectly affects billions of real people and every society on Earth, but also because it can open up exciting possibilities in storytelling.

It can, but often it doesn’t. I’ll start by describing some disability tropes that strike me as predictable, annoying, and sometimes even offensive:

1. The Charity Case. In many stories, the CWD is an innocent, pitiful creature, dependent upon the kindness of others. The characters who (immediately or eventually) treat the CWD with gentleness, patience, and generosity are—we readers easily recognize—Good Guys; those who show disdain, insensitivity, and stinginess are Bad Guys. The CWD functions more as a barometer for other characters’ goodness or evilness than as an agent capable of her own acts of good or evil.

2. The Death-Over-Disability. This trope arises from the idea that some disabilities are so terrifying and tragic that it would be more dignified, more graceful, more true-to-oneself to simply die—either by one’s own hand or by the hand of a compassionate friend or doctor—rather than linger on like that. People can argue over whether and when this might ever be true, but regardless, it’s clear that in fiction, this storyline has been done to death.

3. The Inspiration to Us All. The “inspirational” disability story (or image or quote) is such a ubiquitous cliché, at least in nonfiction and journalism, that there’s a snarky new term for it: “inspiration porn”. The brave RLPWD or CWD teaches other characters (and readers) a lesson about the importance of positivity and perseverance, either by working to achieve some extraordinary feat (being what’s known as a “supercrip”) or by merely managing to engage in “normal” life activities. Such stories often purport to challenge conventional notions of disability, but by now, they’ve become a conventional notion of disability.

4. The Overcomer. Somewhat a combination of 2 and 3 above, it’s perhaps the most straightforwardly ableist trope. The CWD hates his disability so much that his primary, or only, dream or goal is to overcome it, cure himself, learn to do the exact thing that the disability currently prevents him from doing. If he succeeds, it’s a joyous triumph. (Never mind that for many of us RLPWDs, it makes more sense to focus on learning to live with the disability rather than Overcome it.)

I’m not arguing that you need to avoid these tropes at all costs in your own writing. But if you do engage with them, try to complicate or challenge them. Maybe, for example, your Good Guy has a legitimate reason to be stingy, uncomfortable, or downright angry with your CWD. Maybe your CWD is reluctantly considering Death-Over-Disability only because his family can’t afford to continue caring for him, so the problem isn’t disability as much as poverty. Maybe a community’s lionized Inspiration turns out to have cheated to succeed. Maybe your CWD resists or shrugs off the other characters’ efforts to help her Overcome her disability, because she’d rather put her time and energy toward a different goal—one that she can accomplish while still being disabled. Remember that the disability matters, but that it isn’t the only thing that matters about—or matters to—the CWD. (Certainly, everything in this postis useful to keep in mind.) She also has goals, desires, fears, memories, skills, resources, relationships, and idiosyncrasies, which develop in complex interconnection with each other and the disability.

I’m Katherine Duke. I grew up writing fiction, I hold bachelor’s and master’s degrees in creative writing, and I earn my living as a nonfiction writer and editor. I’m also a life-long wheelchair user, and I’m working on a nonfiction book about the social, romantic, and sexual lives of real-life people with disabilities (let’s call us RLPWDs). So the creators of this blog invited me to write about the portrayal of fictional characters with disabilities (CWDs).

I, for one, would like to see disability show up more frequently in fiction—not just because it directly and indirectly affects billions of real people and every society on Earth, but also because it can open up exciting possibilities in storytelling.

It can, but often it doesn’t. I’ll start by describing some disability tropes that strike me as predictable, annoying, and sometimes even offensive:

1. The Charity Case. In many stories, the CWD is an innocent, pitiful creature, dependent upon the kindness of others. The characters who (immediately or eventually) treat the CWD with gentleness, patience, and generosity are—we readers easily recognize—Good Guys; those who show disdain, insensitivity, and stinginess are Bad Guys. The CWD functions more as a barometer for other characters’ goodness or evilness than as an agent capable of her own acts of good or evil.

2. The Death-Over-Disability. This trope arises from the idea that some disabilities are so terrifying and tragic that it would be more dignified, more graceful, more true-to-oneself to simply die—either by one’s own hand or by the hand of a compassionate friend or doctor—rather than linger on like that. People can argue over whether and when this might ever be true, but regardless, it’s clear that in fiction, this storyline has been done to death.

3. The Inspiration to Us All. The “inspirational” disability story (or image or quote) is such a ubiquitous cliché, at least in nonfiction and journalism, that there’s a snarky new term for it: “inspiration porn”. The brave RLPWD or CWD teaches other characters (and readers) a lesson about the importance of positivity and perseverance, either by working to achieve some extraordinary feat (being what’s known as a “supercrip”) or by merely managing to engage in “normal” life activities. Such stories often purport to challenge conventional notions of disability, but by now, they’ve become a conventional notion of disability.

4. The Overcomer. Somewhat a combination of 2 and 3 above, it’s perhaps the most straightforwardly ableist trope. The CWD hates his disability so much that his primary, or only, dream or goal is to overcome it, cure himself, learn to do the exact thing that the disability currently prevents him from doing. If he succeeds, it’s a joyous triumph. (Never mind that for many of us RLPWDs, it makes more sense to focus on learning to live with the disability rather than Overcome it.)

I’m not arguing that you need to avoid these tropes at all costs in your own writing. But if you do engage with them, try to complicate or challenge them. Maybe, for example, your Good Guy has a legitimate reason to be stingy, uncomfortable, or downright angry with your CWD. Maybe your CWD is reluctantly considering Death-Over-Disability only because his family can’t afford to continue caring for him, so the problem isn’t disability as much as poverty. Maybe a community’s lionized Inspiration turns out to have cheated to succeed. Maybe your CWD resists or shrugs off the other characters’ efforts to help her Overcome her disability, because she’d rather put her time and energy toward a different goal—one that she can accomplish while still being disabled. Remember that the disability matters, but that it isn’t the only thing that matters about—or matters to—the CWD. (Certainly, everything in this postis useful to keep in mind.) She also has goals, desires, fears, memories, skills, resources, relationships, and idiosyncrasies, which develop in complex interconnection with each other and the disability.

Published on March 04, 2013 02:28

March 1, 2013

My Happy List

For Clare Dugmore's Bloghop of Joy, this is my incomplete list of delightful things in my life:

First, the big stuff, in no particular order:

Jack the Greyhound. His adoption profile described him as a unique character, which turned out to be a major understatement. He loves his Favourite Human (Yours Truly) and expresses this in a variety of hilarious and endearing ways, such as stealing my dirty gym socks out of the hamper to cuddle when I'm out of the house.My family. Enough said. My best friend. She is a total badass first responder (firefighter/EMT) who lives in the Texas hinterlands.My coauthor. Church. Especially when the Sunday school kids are around. Running around outdoors. I am lucky enough to live in a city with lots of parks, so I can jog, birdwatch, or whatever. Cooking. I find the process soothing, and it sates the 'instant gratification' thing as one gets to eat something delicious as soon as the process is done.

Weird and small stuff, in no particular order:

Young, Dumb and Living Off Mum reruns. Whenever I feel like I'm making a hash of my life, this gives me a bit of perspective.Reading primary sources. Sometimes, it seems humanity has reached a new low. Then I read, and realise if we survived this same stuff in the 15th century (with no running water, sterile hospitals, cell phones, or public transit), we're going to be OK. TVTropes. If I am feeling uninspired, it helps me out. Or helps me procrastinate. Funny-looking vegetables. The local produce shop stocks things like Romanesco broccoli or purple carrots, and it makes my day. Strange/gross science facts. My Lady Friend introduced me to The Brain Scoop, which involves taxidermy and anatomy (not for the squeamish!) and it made my afternoon. Statistical trivia. If someone points me to a database of llama farming by county or internet porn searches by state, I'm delighted.

First, the big stuff, in no particular order:

Jack the Greyhound. His adoption profile described him as a unique character, which turned out to be a major understatement. He loves his Favourite Human (Yours Truly) and expresses this in a variety of hilarious and endearing ways, such as stealing my dirty gym socks out of the hamper to cuddle when I'm out of the house.My family. Enough said. My best friend. She is a total badass first responder (firefighter/EMT) who lives in the Texas hinterlands.My coauthor. Church. Especially when the Sunday school kids are around. Running around outdoors. I am lucky enough to live in a city with lots of parks, so I can jog, birdwatch, or whatever. Cooking. I find the process soothing, and it sates the 'instant gratification' thing as one gets to eat something delicious as soon as the process is done.

Weird and small stuff, in no particular order:

Young, Dumb and Living Off Mum reruns. Whenever I feel like I'm making a hash of my life, this gives me a bit of perspective.Reading primary sources. Sometimes, it seems humanity has reached a new low. Then I read, and realise if we survived this same stuff in the 15th century (with no running water, sterile hospitals, cell phones, or public transit), we're going to be OK. TVTropes. If I am feeling uninspired, it helps me out. Or helps me procrastinate. Funny-looking vegetables. The local produce shop stocks things like Romanesco broccoli or purple carrots, and it makes my day. Strange/gross science facts. My Lady Friend introduced me to The Brain Scoop, which involves taxidermy and anatomy (not for the squeamish!) and it made my afternoon. Statistical trivia. If someone points me to a database of llama farming by county or internet porn searches by state, I'm delighted.

Published on March 01, 2013 00:53

February 27, 2013

A Walking, Talking Disaster

Train wreck characters have been a part of stories since humans started telling cautionary tales around the fire ('Og the Screwup met his end by poking a leopard, so kids, don't be like Og'). However, it's easy to let these characters wreck not just their own lives, but the reader's interest in the story. Usually, it's because the trainwreck character lacks self-awareness or empathy, and merely causes annoyance as they demand that the audience sympathise with their self-created problems. These characters usually have some level of a safety net as well, so the problems remain fairly trivial and there's no risk of the character going completely off the deep end.

That said, there are a few tropes which can allow a train wreck character to work in your story:

The Sympathetic Trainwreck. This character's redeeming feature is a conscience. They may be a screwup, but they genuinely care about other people. The title character of the TV show Nurse Jackie is an excellent example of this. Often, they have some level of self-awareness about their problems. But compassion for others and a genuine effort to make the world better in some small way is absolutely critical for this character to work. The Wish-Fulfillment Train Wreck. Although the name sounds like an oxymoron, this character is all about tapping into the audiences' desire to flout society's rules in some way that looks oh-so-cool. The character could be breaking the rules for a greater causes-- a vigilante superhero or a cowboy cop-- or simply selfish in a daring, entertaining way. We follow those characters because we want to beat up the bad guys who slip past law enforcement, or tell off obnoxious authority figures, or take go on mad drug-fueled adventured, but know that in real life it's a bad idea. The Tragic Trainwreck. This character has some major redeeming features, but just cannot break free of the flaws which are dragging them down. In spite of these good qualities, they are ultimately self-destructive, and we're sad to see their lives go to waste.The Horror Trainwreck. If you're going to write an unsympathetic, unrepentant, antisocial trainwreck character, you need to go all the way. These are the characters we follow because we can't look away-- the swath of destruction they cut is too wild and bloody for us to ignore. The character is also so past the moral lines of society that we have no idea what they'll unleash next, and the unpredictability is fascinating. The key here is to go over the top-- Crime and Punishment has some good examples (or try any character in Trainspotting), since the scale of the problem is what holds the reader's attention.

The bottom line is that the character's behaviour must be seriously problematic, and must carry a strong risk. Otherwise, you just have another person with some bad habits whining in the reader's ear.

That said, there are a few tropes which can allow a train wreck character to work in your story:

The Sympathetic Trainwreck. This character's redeeming feature is a conscience. They may be a screwup, but they genuinely care about other people. The title character of the TV show Nurse Jackie is an excellent example of this. Often, they have some level of self-awareness about their problems. But compassion for others and a genuine effort to make the world better in some small way is absolutely critical for this character to work. The Wish-Fulfillment Train Wreck. Although the name sounds like an oxymoron, this character is all about tapping into the audiences' desire to flout society's rules in some way that looks oh-so-cool. The character could be breaking the rules for a greater causes-- a vigilante superhero or a cowboy cop-- or simply selfish in a daring, entertaining way. We follow those characters because we want to beat up the bad guys who slip past law enforcement, or tell off obnoxious authority figures, or take go on mad drug-fueled adventured, but know that in real life it's a bad idea. The Tragic Trainwreck. This character has some major redeeming features, but just cannot break free of the flaws which are dragging them down. In spite of these good qualities, they are ultimately self-destructive, and we're sad to see their lives go to waste.The Horror Trainwreck. If you're going to write an unsympathetic, unrepentant, antisocial trainwreck character, you need to go all the way. These are the characters we follow because we can't look away-- the swath of destruction they cut is too wild and bloody for us to ignore. The character is also so past the moral lines of society that we have no idea what they'll unleash next, and the unpredictability is fascinating. The key here is to go over the top-- Crime and Punishment has some good examples (or try any character in Trainspotting), since the scale of the problem is what holds the reader's attention.

The bottom line is that the character's behaviour must be seriously problematic, and must carry a strong risk. Otherwise, you just have another person with some bad habits whining in the reader's ear.

Published on February 27, 2013 02:23