S.B. Stewart-Laing's Blog, page 22

April 15, 2013

One Hour Work Week

As I mentioned last week, many denizens of Fictionland seem to have an unusual aversion to working at all but a small subset of jobs. And of those, no one seems to put in anything remotely resembling a 40-hour workweek (or even a 25 hour workweek). Now, if the character is outright stated to have a mundane job, and the main plot follows their life after hours, that's one thing(for example, if Bob is a Health and Safety Inspector by day, and sells magic potions out of his basement at night, mentions of him being tired from work, being late on his commute, etc are probably sufficient to satisfy the reader, who could probably care less about him inspecting offices for unlabeled fire exits).

As I mentioned last week, many denizens of Fictionland seem to have an unusual aversion to working at all but a small subset of jobs. And of those, no one seems to put in anything remotely resembling a 40-hour workweek (or even a 25 hour workweek). Now, if the character is outright stated to have a mundane job, and the main plot follows their life after hours, that's one thing(for example, if Bob is a Health and Safety Inspector by day, and sells magic potions out of his basement at night, mentions of him being tired from work, being late on his commute, etc are probably sufficient to satisfy the reader, who could probably care less about him inspecting offices for unlabeled fire exits).The One-Hour Workweek trope kicks in when:

The character has a '9-5' type job, they are never shown working, even during what should be their normal hours;If freelancing or working remotely, the character is never seen working, or does not work nearly enough hours to support themselves;They have unlimited vacation and free time, and no work conflicts;Their job is never a plot point, even when it should be;If their job is plot-relevant (eg, a supernatural private investigator), they do an abnormal amount of pro-bono work (see point 2), or otherwise wave away the 'earning a living' angle.

Honestly, I think it would be refreshing in the speculative fiction genres to see a character whose 'day job' interacts with the rest of their life in a meaningful way. As much as I enjoy the Dresden Files and Grimm, we've got quite a few paranormal private investigators, and it would be good fun to see a pharmacist who caters to werewolves or a call centre worker who spends their evenings chatting with the local ghosts, but still has to report for duty in the morning (and hope no annoying ghosts follow them to the phones).

Published on April 15, 2013 01:53

April 14, 2013

Nice to the Waiter

"Treat your inferiors as you would be treated by your superiors."Seneca, Epistle 47:11

"Treat your inferiors as you would be treated by your superiors."Seneca, Epistle 47:11In much of Fictionland, as in real life, a whole variety of social stratification plays major and minor roles in how people behave. What power imbalances exist, and how they play out in the characters' lives, is largely a reflection of your chosen setting. But whatever these dynamics are, showing how your characters navigate them is a crucial opportunity for revealing and developing their personalities. This trope will almost inevitably pop up, whether your characters are on the giving end, the receiving end, or both.

That said, this trope has two potential pitfalls that can undermine the author's intended message. The first potential issue is that the non-privileged people (servants, wait staff, members of an oppressed group, etc) show up just to give the hero a chance to show off how 'nice' and 'enlightened' they are by their magnanimous behaviour. Usually the gestures which the author intends as good deeds come off as condescending. Now if this is intentional-- perhaps the protagonists thinks they 'get' the servants, but are clueless that their kind gestures are actually patronising-- keep going. But if you mean this to show the hero is a good person trying to overcome the social hierarchy in their world, the gesture needs to be meaningful on some level. Also, the less-privileged characters need to have motivation beyond cooing over how awesome and nice the main character is to them. Even if that motivation is simply to get through another exhausting day so they can flop into bed. Even if that motivation is never stated outright. But the characters need to at least hint at having their own lives going on, rather than just existing to cheer the hero for being a decent person.

The second pitfall is that the hero gives a lot of lip service to being nice to the less privileged, but doesn't actually follow through in the story itself. Again, this could be intentional if the character doesn't believe the rhetoric, or needs to act a certain way in social settings, but this needs to be explained, otherwise it comes off as hypocrisy by the character at best, and general sloppy writing at worst.

Published on April 14, 2013 01:31

April 13, 2013

Motive Decay

Fanaticism is redoubling your effort while losing sight of your goal.— George Santayana

Fanaticism is redoubling your effort while losing sight of your goal.— George SantayanaGiving characters strong, believable motives is one of the key pieces of a compelling story. This is why I often appreciate those unrepentantly selfish characters I blogged about earlier-- they may be obnoxious to their fellow characters, but they have clear reasons for their actions, and often pursue their goals with vigor.

However, it's not uncommon for a character-- usually the villain-- to start out with a compelling motivation that gets totally derailed over the course of the story. This isn't a case of the character changing their minds, but rather one of them switching gears from being focused on a goal which benefits them and harms the protagonist to single-minded pursuit of being mean to the hero, often in ways which are pointless to them and don't help achieve their goals.

Like most tropes, this isn't necessarily unsalvageable. If you're showing the character getting more and more obsessed with their goal, instead of the reasons behind it, or getting pulled off course by a deep character flaw, it can certainly work. The trick is to do this in a deliberate way, rather than turning the character into a cackling cardboard cutout just to give the hero something to do.

Published on April 13, 2013 00:54

April 12, 2013

The Load

'Can't somebody else do it?'--Homer Simpson

If you've ever worked on a group project, you've had an intimate encounter with that one person who contributes precisely nothing, and actually drains everyone else's time and resources by creating trouble and otherwise needing to be babysat. Unfortunately, this person's fictional counterpart has the potential to be just as annoying unless their character development is handled with finesse.

otherwise needing to be babysat. Unfortunately, this person's fictional counterpart has the potential to be just as annoying unless their character development is handled with finesse.

The most prevalent mistake is to have this character show up unintentionally as a lead or main love interest. This is the lead character who perpetually has to be rescued by everyone else, who for some (usually inadequately explained) reason keeps doing it. Ditto the love interest who continually has to be rescued (bonus points if it's from the same villain!), like a cat who persists in getting stuck repeatedly up the same tree. If you see this happening to your lead character, give them more control over their fate, and perhaps dump some of their babysitters absurdly patient companions (I really, really want to see a sidekick to a passive character who gets sick of rescuing their ungrateful butt and wanders off to do something else).

The other problem is that this character exists solely to cause drama due to their uselessness, but has no adequately explained reason for the other characters putting up with them. Having an inoffensive and vaguely likeable personality isn't enough reason for the other characters to continually risk their lives and/or their mission to save this obvious plot device person. Credible reasons to not dump this person overboard or feed them to the zombies or just send them home include family ties (no one's going to let the were-iguanas eat their baby sister!), a critical skill set (maybe this person has zero common sense, but is the only one who can work the submarine's toilet or the only one with medical training), or some outside obligation (the Load has powerful relatives, and the main characters are going to catch hell if anything bad happens to them).

Finally, the consequences of this person's uselessness should be explored. They are drinking valuable water, eating valuable food, causing time and resources to be wasted on rescue missions... the other characters should at the very least be deeply annoyed instead of blandly tolerant, and at most, consider ways of getting rid of this person (see above).

If you really want to write a Load into your plotline, make sure they aren't just an obvious plot device, but have a strong, conflict-inducing, plot-relevant reason for being there. And please, please, please don't make them the main character.

If you've ever worked on a group project, you've had an intimate encounter with that one person who contributes precisely nothing, and actually drains everyone else's time and resources by creating trouble and

otherwise needing to be babysat. Unfortunately, this person's fictional counterpart has the potential to be just as annoying unless their character development is handled with finesse.

otherwise needing to be babysat. Unfortunately, this person's fictional counterpart has the potential to be just as annoying unless their character development is handled with finesse.The most prevalent mistake is to have this character show up unintentionally as a lead or main love interest. This is the lead character who perpetually has to be rescued by everyone else, who for some (usually inadequately explained) reason keeps doing it. Ditto the love interest who continually has to be rescued (bonus points if it's from the same villain!), like a cat who persists in getting stuck repeatedly up the same tree. If you see this happening to your lead character, give them more control over their fate, and perhaps dump some of their babysitters absurdly patient companions (I really, really want to see a sidekick to a passive character who gets sick of rescuing their ungrateful butt and wanders off to do something else).

The other problem is that this character exists solely to cause drama due to their uselessness, but has no adequately explained reason for the other characters putting up with them. Having an inoffensive and vaguely likeable personality isn't enough reason for the other characters to continually risk their lives and/or their mission to save this obvious plot device person. Credible reasons to not dump this person overboard or feed them to the zombies or just send them home include family ties (no one's going to let the were-iguanas eat their baby sister!), a critical skill set (maybe this person has zero common sense, but is the only one who can work the submarine's toilet or the only one with medical training), or some outside obligation (the Load has powerful relatives, and the main characters are going to catch hell if anything bad happens to them).

Finally, the consequences of this person's uselessness should be explored. They are drinking valuable water, eating valuable food, causing time and resources to be wasted on rescue missions... the other characters should at the very least be deeply annoyed instead of blandly tolerant, and at most, consider ways of getting rid of this person (see above).

If you really want to write a Load into your plotline, make sure they aren't just an obvious plot device, but have a strong, conflict-inducing, plot-relevant reason for being there. And please, please, please don't make them the main character.

Published on April 12, 2013 02:11

April 11, 2013

Karmic Death

Violence, in truth, recoils upon the violent, and the schemer falls into the pit he has dug for another.

— Sherlock Holmes, The Adventure of the Speckled Band

No matter how awful the villain is, having the hero kill them outright can still seem morally sketchy, particularly in a modern context. Enter the karmic death, in which the villain's bad behaviour comes back to bite them, resulting in their demise. Not only are the heroes off the hook, but there's an extra satisfaction in having the villain's actions directly cause their downfall. That said, it's a trope to apply carefully. Done well, it gives an extra level of closure to the conflict. Done poorly, it comes off as heavily contrived and kills the mood (along with the suspension of disbelief).

A satisfying karmic downfall is usually best achieved by giving some level of buildup. Let the reader see that this evil scheme has some potential to bite back, or lay the groundwork for the hero to turn the scheme against their antagonist. Alternately, build up a fatal flaw in a similar way, so that when the villain trips themselves up, the reader and look back on the events of the book and see it as an inevitable downfall, rather than a gimmick.

— Sherlock Holmes, The Adventure of the Speckled Band

No matter how awful the villain is, having the hero kill them outright can still seem morally sketchy, particularly in a modern context. Enter the karmic death, in which the villain's bad behaviour comes back to bite them, resulting in their demise. Not only are the heroes off the hook, but there's an extra satisfaction in having the villain's actions directly cause their downfall. That said, it's a trope to apply carefully. Done well, it gives an extra level of closure to the conflict. Done poorly, it comes off as heavily contrived and kills the mood (along with the suspension of disbelief).

A satisfying karmic downfall is usually best achieved by giving some level of buildup. Let the reader see that this evil scheme has some potential to bite back, or lay the groundwork for the hero to turn the scheme against their antagonist. Alternately, build up a fatal flaw in a similar way, so that when the villain trips themselves up, the reader and look back on the events of the book and see it as an inevitable downfall, rather than a gimmick.

Published on April 11, 2013 01:54

April 10, 2013

Jerk With a Heart of Jerk

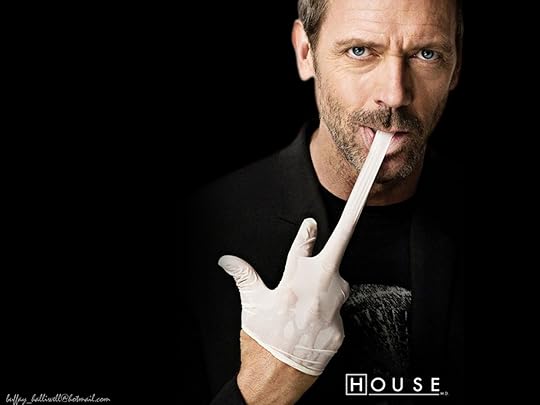

The idea of a jerk with a heart of gold-- someone who, for whatever reason, hides their kindness behind a unpersonable facade-- is so well-worn in fiction that readers start looking for it the moment a grouch shows up on the scene.

The idea of a jerk with a heart of gold-- someone who, for whatever reason, hides their kindness behind a unpersonable facade-- is so well-worn in fiction that readers start looking for it the moment a grouch shows up on the scene.This is probably the reason I like fictional jerks who are unrepentant about their selfish ways. Bluntly, it's refreshing.

The other reason these characters can be a positive influence on your writing-- albeit in controlled dosages-- is that it's tempting to write characters who are good to the point of irritating the reader. A genuinely selfish character, on the other hand, can immediately add friction to the story even when they're behaving in a socially acceptable manner. After all, the reader will immediately be suspicious of their good behaviour, and start looking for schemes and hidden motives, which will almost certainly exist.

Having a character with strong motivation, even if that motivation isn't the most appealing, is an important plot driver. And sometimes a jerk can do wonders for your plot. They can be a wild card in some respects, as they are likely to place their own short-term gains over the good of the group, whether that's ratting out the bad guys to get a reward, or turning in the heroes for some petty revenge.

These characters are also uniquely positioned to be chronic do-gooders who don't annoy the reader. If someone saves the day to save their own behind, or because it's their job, this can be much more appealing than a saccharine cutout who works at their charity job saving inner-city kids, and then goes home to train orphaned sloths as guide-animals for the blind. That level of selflessness not only strains suspension of disbelief, but can be incredibly boring; a firefighter who rescues people from burning buildings because they like the attention and accolades is interesting.

Published on April 10, 2013 02:08

April 9, 2013

Informed Wrongness

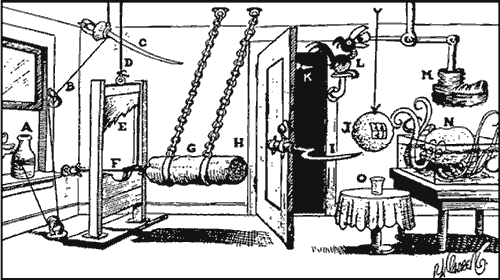

In much of Fantasyland, Evil Overlords are apparently too busy brushing their Persian cats, cackling, and concocting Rube Goldberg-style traps for the hero to do anything...well, evil. This problem of having too little time for actual villany is also shared by the antagonists in many genres, most particularly by the enemies of cannon Mary Sues. This is the ideal breeding ground for Informed Wrongness, which rears its head whenever the author doesn't want to spend any time depicting actual bad deeds, think about the logistics of the Evil Empire, or risk having their main character be wrong during a debate.

In much of Fantasyland, Evil Overlords are apparently too busy brushing their Persian cats, cackling, and concocting Rube Goldberg-style traps for the hero to do anything...well, evil. This problem of having too little time for actual villany is also shared by the antagonists in many genres, most particularly by the enemies of cannon Mary Sues. This is the ideal breeding ground for Informed Wrongness, which rears its head whenever the author doesn't want to spend any time depicting actual bad deeds, think about the logistics of the Evil Empire, or risk having their main character be wrong during a debate.The most obvious example of this is the Evil Empire That Doesn't Do Anything, in which our heroes are part of a rag-tag rebellion against a vile, repressive government which...collects taxes and stuff. Unless we see that the government is being inexcusably awful, your protagonists tend to come off as Fantasyland domestic terrorists; at it's worst, the Evil Empire looks like it's taking a sensible approach.

Informed Wrongness also becomes a tool to shut down discussion, especially in cases where the protagonist might be wrong, the antagonist might have a point, or both.We're told that the antagonist is a Bad Person for no discernible reason, other than that they're clashing with the main character.

For the sake of audience sympathy, it's important to work out if the antagonist is evil-- in which case, we need to see some real villainy proportional with the protagonist's response-- or if they're just another angle on a complex situation, in which case, it's totally okay for them to have some reasonable points, as long as the protagonist has more, better points.

Published on April 09, 2013 02:07

April 8, 2013

Historical Hero Upgrade

'It doesn't matter. I won't be in the history books anyway, only you. Franklin did this and Franklindid that and Franklindid some other damn thing. Franklin smote the ground and out sprang George Washington, fully grown and on his horse. Franklin then electrified him with his miraculous lightning rod and the three of them - Franklin, Washington, and the horse - conducted the entire revolution by themselves.'— John Adams, 1776

As I've mentioned before, complexity-- especially when that means writing morally ambiguous characters-- can be intimidating. When dealing with historical figures, things can get even murkier. There are plenty of people who were great at their jobs, but were less-than-appealing human beings, or were nice enough by the standards of their time, but hold some views modern audiences would rightfully find unsavory*. (I won't address historical figure overhauls, such as Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter, since those are a tool of the alternate history genre, and are very deliberately a total departure from the person as they were).

The first type of Historical Hero Upgrade stems from the idea that one's lead character must be likable. Obviously, this isn't true-- plenty of characters who are various degrees of social disaster zones have become popular protagonists. Furthermore, squeaky-clean characters carry a high risk of being boring, since they come off as pose-able good-guy action figures rather than real people. One option is to spend more time on the character's motives, which are presumably sympathetic, so that the audience cheers for them to succeed even if their methods venture into cringeworthy territory. This is particularly true of people who ultimately did a great deal of good but were personally unpleasant and occasionally ruthless in their methods of accomplishing their larger goals.

The second type falls back to the tension between modern morality and historical context. Personally, I think the best way to handle this isn't to brush the issues under the rug, but place the behaviour or beliefs in context. Remember that your characters need to be themselves first and foremost, and that it's OK for the reader to react with discomfort. Just because a character is sympathetic doesn't mean you or the reader have to condone all their beliefs and actions. Personally, I think it's better to give an honest look at a society and people whose morals and behaviour don't align with modern standards than to try to pretend that such problems never occurred, or were only the provenance of jerks.

*I should note that updating the characterisation of a historical figure to more accurately reflect facts is not this, even if the character is portrayed unfavourably in a lot of popular fiction and your portrayal is more positive.

As I've mentioned before, complexity-- especially when that means writing morally ambiguous characters-- can be intimidating. When dealing with historical figures, things can get even murkier. There are plenty of people who were great at their jobs, but were less-than-appealing human beings, or were nice enough by the standards of their time, but hold some views modern audiences would rightfully find unsavory*. (I won't address historical figure overhauls, such as Abraham Lincoln Vampire Hunter, since those are a tool of the alternate history genre, and are very deliberately a total departure from the person as they were).

The first type of Historical Hero Upgrade stems from the idea that one's lead character must be likable. Obviously, this isn't true-- plenty of characters who are various degrees of social disaster zones have become popular protagonists. Furthermore, squeaky-clean characters carry a high risk of being boring, since they come off as pose-able good-guy action figures rather than real people. One option is to spend more time on the character's motives, which are presumably sympathetic, so that the audience cheers for them to succeed even if their methods venture into cringeworthy territory. This is particularly true of people who ultimately did a great deal of good but were personally unpleasant and occasionally ruthless in their methods of accomplishing their larger goals.

The second type falls back to the tension between modern morality and historical context. Personally, I think the best way to handle this isn't to brush the issues under the rug, but place the behaviour or beliefs in context. Remember that your characters need to be themselves first and foremost, and that it's OK for the reader to react with discomfort. Just because a character is sympathetic doesn't mean you or the reader have to condone all their beliefs and actions. Personally, I think it's better to give an honest look at a society and people whose morals and behaviour don't align with modern standards than to try to pretend that such problems never occurred, or were only the provenance of jerks.

*I should note that updating the characterisation of a historical figure to more accurately reflect facts is not this, even if the character is portrayed unfavourably in a lot of popular fiction and your portrayal is more positive.

Published on April 08, 2013 01:32

April 7, 2013

Green-Skinned Space Babe

Throughout the speculative fiction genres, the human characters are pretty likely to run into some sentient non-humans. Interestingly enough, these creatures, especially the female specimens, are also likely to be incredibly attractive by human standards.

Throughout the speculative fiction genres, the human characters are pretty likely to run into some sentient non-humans. Interestingly enough, these creatures, especially the female specimens, are also likely to be incredibly attractive by human standards.This seems rather unlikely. Even if there's some common ancestor, as in the Star Trek universe, the two species have most likely diverged enough to not be appealing to each other. And if there isn't a common ancestor, it seems very strange that these supernatural or alien creatures would look like humans at all (at least without a good explanation).

There are some scenarios which would provide such an explanation. Maybe the supernatural entity-- such as a ghost, a werewolf, etc.-- was human at one point. Maybe the creature is a shapeshifter, and purposely chose to look like an attractive human (if it's intelligent, it would presumably want to take advantage of how human society privileges it's good-looking members). Or maybe being attractive to humans is part of this creature's life cycle-- it needs to lure humans close to feed on them, or perhaps feeds off sexual energy itself.

But outside of those situations, or some permutation thereof, there's no reason that aliens or other non-human creatures should look like humans, let alone be smokin' hot.

Published on April 07, 2013 03:02

April 6, 2013

For Want of a Nail

One of my favourite bits of writing alternate history is figuring out the causality. It's amazing fun to think about how the events in your story change the course of history as we know it, and create entirely new event chains.

One of my favourite bits of writing alternate history is figuring out the causality. It's amazing fun to think about how the events in your story change the course of history as we know it, and create entirely new event chains.Besides the aspect of pure fun-- at least, I find thinking about chains of causality endlessly entertaining-- it's an excellent way to break the narrative of historical inevitability and examine the impact of real historical events in a meaningful way. It's one thing for characters in the course of a historical narrative to think on what might have happened differently, or express their hopes or fears about the outcome of a real event, and another to actively explore the ripples of historical change that occur as a result of altering one crucial moment.

A few things to consider:

First, there will be some inertia in the areas that aren't at ground zero of your point of divergence. For example, if your point of divergence is the Wampanoag leaving Plymouth Colony to their own devices in 1621 instead of showing them how to plant corn and catch fish, there won't be an impact on European history until the following autumn, and the major results of the failure of Plymouth won't show up in North American history for a few years. However, how fast the divergence spreads and effects world events is a function of both the nature of the event, the area covered by the original event, the magnitude of the event, and the speed of travel and news dissemination in your setting.

Second, unless you're dealing with a time-travel scenario and have a 'stable time loop' setup or the like, put aside the idea that history will 'spring back' into something resembling the world we know (this goes back to the fallacy of historical 'inevitability'). Each point of divergence will spawn more events which diverge from history as we know it, and so on-- a chain reaction rather than a lonely glitch.

Published on April 06, 2013 02:44