S.B. Stewart-Laing's Blog, page 27

January 14, 2013

Doctor, Doctor!

As Diana Wynne Jones noted in A Tough Guide to Fantasyland, fictional medicine-- especially in historical and fantasy books-- seems to have a closer relation to plot convenience than to the setting itself. There are a large number of mystery herbs which fix whatever needs fixing (yes, Walter Scott used that trope; no, I will not stop picking on his work), and doctors or healers who show up and get the protagonist patched up (or fail to save the character whose death is slated to be motivation and/or a touching moment), and then conveniently fail when it's dramatic for the plot.

As Diana Wynne Jones noted in A Tough Guide to Fantasyland, fictional medicine-- especially in historical and fantasy books-- seems to have a closer relation to plot convenience than to the setting itself. There are a large number of mystery herbs which fix whatever needs fixing (yes, Walter Scott used that trope; no, I will not stop picking on his work), and doctors or healers who show up and get the protagonist patched up (or fail to save the character whose death is slated to be motivation and/or a touching moment), and then conveniently fail when it's dramatic for the plot. Now, in a speculative fiction setting, you have a blank canvas to some degree. However, for the sake of avoiding later plot contrivance-- readers can scent it out-- it's best to establish the rules of whatever magical or sci-fi healing processes you plan to include in the story. If you feel yourself wanting to complain that this will make life harder to your main characters, or complicate a plot point, remember that those are good developments in the context of the story. Having a character come face to face with the implacable rules of their universe introduces genuine tension and forces you to consider more creative plot developments.

In historical/AH settings, research is your friend, the more detailed the better. Never assume that research on one region in a time period is a universal statement about worldwide medical knowledge. Depending on culture, education, prosperity, and religious beliefs, even adjacent areas can have vastly different approaches to healthcare, and very different medical technology. I guarantee you'll end up surprised though-- my coauthor and I certainly were when were did the background research for The Devil and the Excise-Man and discovered all sorts of weird and shockingly modern things in English and Scottish medical practice respectively.

I know some people are less enthusiastic about research (or world-building) than Mike and I are, but trust me, it's worthwhile for your creative process. Plus it's always good to have a stash of world-building material, particularly on oft-neglected topics, ready to patch plot points or serve as inspiration.

Published on January 14, 2013 01:54

January 11, 2013

Badly Incompetent Baddies

If you watch enough action movies or TV series, you'll notice the hero mowing down the Evil Overlord's minions like it's nothing. For their part, the minions tend to do things like shoot anywhere but where the heroes are standing, wait their turn to attack instead of piling on to a hero they massively outnumber, and falling for obvious ruses. Then again, this could be down to poor management, since a disturbing number of Evil Overlords create wildly impractical death traps, divert resources away from practical tasks to 'evil for the lulz' activities, and blurt out their schemes to inadvisable audiences.

If you watch enough action movies or TV series, you'll notice the hero mowing down the Evil Overlord's minions like it's nothing. For their part, the minions tend to do things like shoot anywhere but where the heroes are standing, wait their turn to attack instead of piling on to a hero they massively outnumber, and falling for obvious ruses. Then again, this could be down to poor management, since a disturbing number of Evil Overlords create wildly impractical death traps, divert resources away from practical tasks to 'evil for the lulz' activities, and blurt out their schemes to inadvisable audiences.This is rather a shame, since a good villain can often be the driving force behind a story. Their role is to push the heroes outside of their comfort zone. If the story is going to be at all suspenseful, the heroes have to be in real danger, and the Evil Overlord has to have a high probability of winning, right up until the last moment. The best, scariest bad guys are pragmatic and highly competent.

Now although I'm talking about stories which fall loosely into the adventure genre (fantasy, action, etc), but this concept also applies to other story types-- this could be the romantic rival who falls glaringly short of the hero (or is just a bad match for the love interest), the coach who would rather compromise team performance than let the hero play, and so on.

The key is to trust your heroes to come through via their own ingenuity and strength, rather than insuring their success by artificially undermining the villain. The accomplishments of the hero will be much more exciting and impressive when they're pitted against someone who's a genuine threat.

Published on January 11, 2013 02:28

January 9, 2013

All You Need Is Love

No matter what genre, the key for an emotionally engaging story is having the readers invested in your characters and their struggle. When a romantic main plot or subplot is in play, this means we have to not just love the leads, but love their relationship.

No matter what genre, the key for an emotionally engaging story is having the readers invested in your characters and their struggle. When a romantic main plot or subplot is in play, this means we have to not just love the leads, but love their relationship. If the romance-- or unrequited romantic tension-- between characters is a key plot point, it needs to be believable and vividly rendered. The audience has to feel their love.

It's not just enough that the characters to declare their adoration for each other. This actually tends to be more annoying. It feels like the author is trying to bludgeon everyone into accepting the Twoo Luv in action, instead of showing us a pair we can cheer for. At best, all that your audience will be convinced of is that they're in lust. Show us why these two people 'get' each other-- maybe they share some common passionate interest, or compliment each other's personality and skills, or mesh over some mutual need. These are your characters, so you can develop their life stories and personalities so that the relationship makes sense and is a strong part of why the audience relates to the characters, not just a drama-generating plot crutch.

Published on January 09, 2013 12:28

January 7, 2013

Character Self-Awareness

As I've mentioned before, we're all unreliable narrators. But through trial and error, I also believe everyone develops some degree of self-awareness. We know our flaws and strengths, and try to improve them or play to them.

As I've mentioned before, we're all unreliable narrators. But through trial and error, I also believe everyone develops some degree of self-awareness. We know our flaws and strengths, and try to improve them or play to them.When you create a character, you get to determine their degree of self-awareness. Perhaps this person is acutely aware of their flaws and strengths, or is utterly oblivious, or has latched onto an erroneous self-perception. Any way you approach this, you have potential for intriguing character development.

By bringing us into the character's thoughts, the author can show the dichotomy between the character's self-image and their interactions with the world. It's also a major part of how the reader builds up their perception of the character-- we cringe when we see a well-intentioned character mess up because of their own unacknowledged obliviousness to other people's feelings, or cheer when another character gains enough perspective to make a difficult self-improving choice.

Published on January 07, 2013 02:12

January 4, 2013

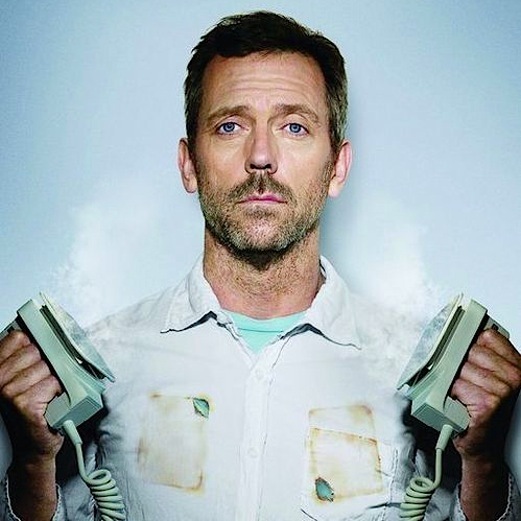

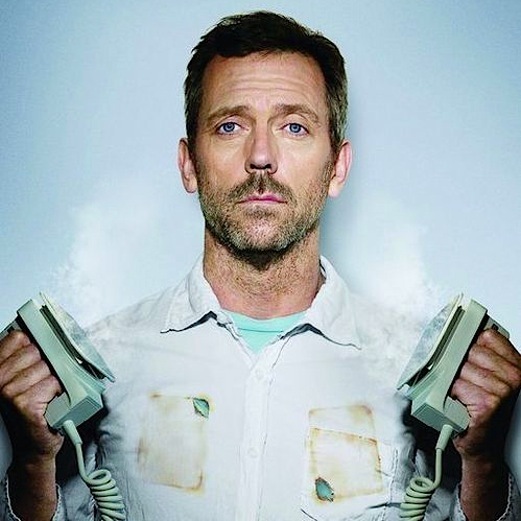

Is There A Doctor in the House?

As Diana Wynne Jones noted in A Tough Guide to Fantasyland, fictional medicine-- especially in historical and fantasy books-- seems to have a closer relation to plot convenience than to the setting itself. There are a large number of mystery herbs which fix whatever needs fixing (yes, Walter Scott used that trope; no, I will not stop picking on his work), and doctors or healers who show up and get the protagonist patched up (or fail to save the character whose death is slated to be motivation and/or a touching moment).

As Diana Wynne Jones noted in A Tough Guide to Fantasyland, fictional medicine-- especially in historical and fantasy books-- seems to have a closer relation to plot convenience than to the setting itself. There are a large number of mystery herbs which fix whatever needs fixing (yes, Walter Scott used that trope; no, I will not stop picking on his work), and doctors or healers who show up and get the protagonist patched up (or fail to save the character whose death is slated to be motivation and/or a touching moment). Now, if you have a speculative fiction setting, you have a blank canvas to some degree. However, for the sake of avoiding later plot contrivance-- readers can scent it out-- it's best to establish the rules of whatever magical or sci-fi healing processes you plan to include in the story. If you feel yourself wanting to complain that this will make life harder to your main characters, or complicate a plot point, remember that those are good developments in the context of the story. Having a character come face to face with the implacable rules of their universe introduces genuine tension and forces you to consider more creative plot developments.

In historical/AH settings, research is your friend, the more detailed the better. Never assume that research on one region in a time period is a universal statement about worldwide medical knowledge. Depending on culture, education, prosperity, and religious beliefs, even adjacent areas can have vastly different approaches to healthcare, and very different medical technology. I guarantee you'll end up surprised though-- my coauthor and I certainly were when were did the background research for The Devil and the Excise-Man and discovered all sorts of weird and shockingly modern things in English and Scottish medical practice respectively.

I know some people are less enthusiastic about research (or world-building) than Mike and I are, but trust me, it's worthwhile for your creative process. Plus it's always good to have a stash of world-building material, particularly on oft-neglected topics, ready to patch plot points or serve as inspiration.

Published on January 04, 2013 01:54

January 2, 2013

Inner and Outer Narratives

[image error]

In our interactions with people, we often assume that what we see is the full extent of their personality and inner life. Unless we have an extended relationship with that person, and peel away the exterior layers, we don't often get to see if there is a dissonance between what they experience and what they present to the world.

When constructing a fictional character, you have an opportunity to explore this dichotomy as much as you like. Your character may wear their heart on their sleeve, or they maintain one public persona while living a very different interior life. The effort required to prop up their image may be a subplot in and of itself, causing them conflict for myriad reasons-- the stress of pretending to be something one isn't, the demands of a job that requires a particular persona, or any other conflict between presentation and reality.

Furthermore, perception of the character by others may not match up with their inner life due to simple misinterpretation. For example, a friend told me she was amazed by how 'spontaneous' she found me. As a person who is less than keen on major surprises, I like to plan things in advance, but I do so quietly-- to an outside observer, my actions seemed spontaneous, because I hadn't spoken about my plans in any serious way. Similarly, a character might present as disinterested when instead they are observing closely rather than engaging; someone might be seen as unflappable when in fact they are numbed by trauma; countless examples are possible. The character's persona may not even be of their own conscious making.

A public persona can be situational, instead of a permanent barrier between the character's true self and the world. A shy person may enjoy acting and take over a stage, but revert to their more quiet self when with friends, or someone who cultivates a tough, confrontational presentation in their job may show tenderness with their children.

As the author, you can bring the reader into the character's head and show their inner life, as well as the reactions of others around them. This certainly isn't required, and characters who present their true selves most of the time can be just as interesting as those who hide behind a mask. Either way, it's always good to use your insights into the character's thoughts and feelings to give the reader further insights and deeper conflicts.

When constructing a fictional character, you have an opportunity to explore this dichotomy as much as you like. Your character may wear their heart on their sleeve, or they maintain one public persona while living a very different interior life. The effort required to prop up their image may be a subplot in and of itself, causing them conflict for myriad reasons-- the stress of pretending to be something one isn't, the demands of a job that requires a particular persona, or any other conflict between presentation and reality.

Furthermore, perception of the character by others may not match up with their inner life due to simple misinterpretation. For example, a friend told me she was amazed by how 'spontaneous' she found me. As a person who is less than keen on major surprises, I like to plan things in advance, but I do so quietly-- to an outside observer, my actions seemed spontaneous, because I hadn't spoken about my plans in any serious way. Similarly, a character might present as disinterested when instead they are observing closely rather than engaging; someone might be seen as unflappable when in fact they are numbed by trauma; countless examples are possible. The character's persona may not even be of their own conscious making.

A public persona can be situational, instead of a permanent barrier between the character's true self and the world. A shy person may enjoy acting and take over a stage, but revert to their more quiet self when with friends, or someone who cultivates a tough, confrontational presentation in their job may show tenderness with their children.

As the author, you can bring the reader into the character's head and show their inner life, as well as the reactions of others around them. This certainly isn't required, and characters who present their true selves most of the time can be just as interesting as those who hide behind a mask. Either way, it's always good to use your insights into the character's thoughts and feelings to give the reader further insights and deeper conflicts.

Published on January 02, 2013 02:05

December 31, 2012

Happy 2013!

Published on December 31, 2012 16:00

December 24, 2012

Merry Christmas!

A traditional Christmas Eve/midnight mass carol from Barra.

Published on December 24, 2012 15:30

December 11, 2012

Holiday Hiatus

Writing the Other is going on standby until January 2013. So enjoy Christmas/Chanukah/Yule/Kwanza/Solstice/Festivus and get your resolutions ready for the New Year!

Writing the Other is going on standby until January 2013. So enjoy Christmas/Chanukah/Yule/Kwanza/Solstice/Festivus and get your resolutions ready for the New Year!

Published on December 11, 2012 14:46

December 5, 2012

Communication Styles

We're commonly told to make sure that our characters speak their dialogue in a distinctive voice. While this is good advice-- everyone does have personal speech patterns-- communication involves a lot more than talking. Behavioural scientists estimate up to 80% of human communication is nonverbal, and that's not just body language. We tell each other volumes with our clothing, our tone of voice, what we choose to remember or ignore, or actions, such as touch.

Each of us has a preferred style of communication. Some of us prefer to verbalise our feelings directly, some take an indirect approach. Some people feel less comfortable with words, and prefer physical gestures instead.

Thinking about how a character communicates means considering the whole package-- their preferred communication style, their nonverbal communication style, and their speech (and yes, if you're writing a deaf character, signing is speech) to capture the way that individual interacts with the other characters and their world.

Each of us has a preferred style of communication. Some of us prefer to verbalise our feelings directly, some take an indirect approach. Some people feel less comfortable with words, and prefer physical gestures instead.

Thinking about how a character communicates means considering the whole package-- their preferred communication style, their nonverbal communication style, and their speech (and yes, if you're writing a deaf character, signing is speech) to capture the way that individual interacts with the other characters and their world.

Published on December 05, 2012 02:12