S.B. Stewart-Laing's Blog, page 17

July 26, 2013

The Best of All Possible Worlds?: Time Travel, Part III

“The moving hand once having writ moves on. Nor all thy piety nor wit can lure it back to cancel half a line.”

“The moving hand once having writ moves on. Nor all thy piety nor wit can lure it back to cancel half a line.”--Omar Khayyám

When your characters have the ability to rewrite the past as we know, it simultaneously opens up fantastic opportunities for innovative explorations of history, and opportunities for re-entrenching the dominant narrative, with all the attending unpleasant implications. As a fan of alternate history-- particularly that which makes us look hard at how we arrived at our present-- I'd definitely encourage writers to write stories where characters can alter events as they occurred in 'our' timeline. At the same time, whenever an author makes an executive decision about 'point of divergence' in their alternate history timeline, they will have to decide how to shape the resulting alteration of events, and, more importantly, decide whether the narrative will treat these outcomes as positive, negative, or ambiguous.

The more subtle trap is that of hindsight bias, in which we assume that historical events-- particularly bad ones-- were the only possible outcome, and perhaps that the events were inevitable on a larger, less specific scale. Thus we have stories of characters attempting and failing to prevent the great and small tragedies of history and failing. This in and of itself is not a problem if handled with sensitivity. However, if the story returns to support the implied narrative that the tragic event was inevitable in the grand scheme of things, thus quietly absolving the very real perpetrators of responsibility, you've shaped this into a core message of your narrative (as usual, we can blame Walter Scott, father of historical fiction and lead henchmen of the colonialism apologists, for kick-starting this one). This gets exponentially worse and more prominent if you prop up the 'inevitability' theory by dragging out well-worn arguments which boil down to the recipients of the violence or general horribleness having had it coming in some way. I know it's an easy trap to fall into, but it can be avoided with some careful examination of the story.

Published on July 26, 2013 02:50

July 24, 2013

The Time Traveller's Dilemma: Time Travel, Part II

I tend to be a bit wary of time travel stories (Dr Who notwithstanding-- one show which handles the points below well). The main point of my discomfort is that the issue of whether or not one can change the past, and the logistics of that answer, can open up a whole can of very squirmy worms. If inadequately addressed, you can end up knee deep in plot holes, unfortunate implications, or both. As with any feature of your fictional universe, a big part of dealing with this issue is to decide what the story rules are as far as changing the past, and then, once those rules are established, sticking to them.

I tend to be a bit wary of time travel stories (Dr Who notwithstanding-- one show which handles the points below well). The main point of my discomfort is that the issue of whether or not one can change the past, and the logistics of that answer, can open up a whole can of very squirmy worms. If inadequately addressed, you can end up knee deep in plot holes, unfortunate implications, or both. As with any feature of your fictional universe, a big part of dealing with this issue is to decide what the story rules are as far as changing the past, and then, once those rules are established, sticking to them. There's also a deeper implication for your story's meaning, however. This is most prominent when the story touches on or centres around major historical events (assuming you've dealt with the time traveller's paradox... quantum theories about the multiverse should help). If your characters can and do change events, the new outcome and how the narrative treats this change-- as positive or negative-- will carry much of the story's values. Similarly, if the characters can theoretically change history and fail to do so you can land straight in the unfortunate implication zone, particularly if these events are man-made tragedies, as we'll discuss more on Friday. The only way I've seen this handled well is when the characters face a choice between 'bad' and 'catastrophic' outcomes, and have to make a terrible choice to let one horror unfold to spare the world something even worse.

If you want to write about characters struggling and failing to change the past, I think the best route is to have a universe where the past is permanent (ie, the time traveller's paradox is in full effect). Much like stories of self-fulfilling prophecies, seeing the characters attempt to alter the past for the better and inadvertently become a critical part of shaping history as we know can be a painful meditation on acceptance if you let the story develop depth.

Published on July 24, 2013 01:59

July 22, 2013

The Lonely Planet Guide to Spacetime: Time Travel, Part I

'The past is like another country. They do everything the same there.'

'The past is like another country. They do everything the same there.'--Slartibartfast, Life, the Universe and Everything

A lot of fictional time travellers seem to behave as though being hurled into another era-- often, hundreds of years into the past or future-- takes less preparation than packing for a long holiday. Put on a change of clothes, brush off your Shakespeare, and you're good to go!

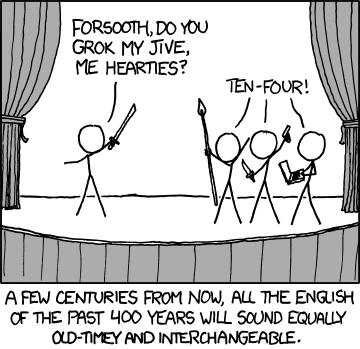

This dramatically underestimates the cultural changes that occur over time-- and this is assuming your character isn't jumping locations as well as time periods. Think about all the funny 'parents on the internet' screengrabs you've seen and remember that this is only a few decades difference. Now imagine that sort of cultural change multiplied by ten, and you've got an idea of how you'd fare in, say, the 16th century. Again, that's assuming you're time travelling within your native culture.

Furthermore, there's a reason that fictional time travellers outside of Octavia Butler novels are overwhelmingly white/Anglo. If you're of another ethnicity or race, you have a whole other set of issues to deal with, particularly if you don't get to pick the time and place. Butler's Kindred does an excellent job of exploring the harshness of both the social and physical environment her character is thrown into on a 19th century American plantation. This won't be an issue for every character in every time, but is certainly something to keep in mind.

Things your character should either study up on, or be totally befuddled by, should they go hurdling back (or forward) in time include (but are certainly not limited to):

Language shift

Money (where do you get some that's appropriate for that time period? What are 'reasonable' prices for things?)

Clothing

Food and food prep (do they know how to use a dung fire? Or a food replicator?)

Social niceties and small talk

Diseases (have they gotten all their vaccines? Might they be carrying something infectious to their destination?)

Dealing with these issues-- especially though the eyes of groups who don't get to do as much time travelling-- can be great sources of conflict for your story.

Published on July 22, 2013 02:32

July 19, 2013

Fix-It Romance

One of the staples of romantic plotlines is the very physically attractive love interest with lots and lots of Issues. The more stable character manages to fix the troubled one with the power of contrived love, and off they ride into the sunset. Typically, the troubled character is male and the fix-it character female, but there's some examples of this trope played out with the genders reversed (same-sex examples are generally restricted to fanfiction.net).

One of the staples of romantic plotlines is the very physically attractive love interest with lots and lots of Issues. The more stable character manages to fix the troubled one with the power of contrived love, and off they ride into the sunset. Typically, the troubled character is male and the fix-it character female, but there's some examples of this trope played out with the genders reversed (same-sex examples are generally restricted to fanfiction.net). Now in a realistic romance, both parties will have flaws, and internal and external conflicts to overcome. And a story which features both characters changing and growing and learning to be better partners to each other can be a compelling narrative. The characteristic of a fix-it romance is that only one character has issues, or at least that one character's issues are serious and deep while the other character's problems are fairly minor, so that the fix-it character falls into a caretaker role while mending their broken partner.

The problem with this plot is twofold. First, it unbalances the pairing right from the get-go. Basically, one partner is doing all the work and the other is doing all the sexy emo poses. We don't get to see them function as a team, but rather as nurse and patient. Nor do we get to see the characters as people-- one is there as a glorified stuffed animal to comfort the troubled character, and the troubled character exists to wring pity from the audience.

Second, the implication is that romance is not about finding a compatible person to form a team and learn and grow with, but rather someone with an appealing exterior and an appalling personality/psychological/psychiatric issues to fix until they're a suitable mate. Essentially, the 'fixing' process isn't about genuinely helping the character with the problems, but about gratifying the fix-it character, as they seem to find the repair process gratifying, and secondly, are rewarded with their ideal lover-- all patched up!

Let your characters be characters, rather than plot devices, and you'll have a better--and more convincing-- love story.

Published on July 19, 2013 02:25

July 17, 2013

Like a Surgeon: Healers & Healing, Part II

While historical fiction is appropriately populated with physicians, Fantasyland seems to run on healers. Their specialties include instant magical healing, mysterious all-curing herbs, and natural talent that seems to obviate the need for any sort of medical training.

Problem one which needs to be dealt with is that there shouldn't be free lunch, even in Fantasyland. There needs to be some level of difficulty to the magical healing, or some price attached, or it's basically a videogame character running through an 8-bit heart and getting their health restored. Even in the Harry Potter series, which does have some instances of instant magical healing, there are several checks on the system. First, it appears to take a level of skill to perform healing spells (more on that in a moment), since doing it wrong results in backwards noses or boneless arms. Second, it's not all instant-- the bigger and more complex the injury, the more complicated the healing process, and it can require potions, pain, and lots of recovery time. Another option is to have the healing process take something from the healer, either by sapping their energy or transferring some of the illness or injury onto them. Mercedes Lackey does this in her Valdemar series, and it provides an effective plot point when there's diseases or injuries that are too big or dangerous for a healer to take on alone.

The second problem is that there's often an emphasis on natural talent rather than training. Again, healing should have consequences (otherwise, why are injuries even a plot point?), and one way to establish that it's difficult and complex is to have the healers undergo serious training. Maybe they have to learn very precise spells, complicated potions, meditation techniques to project their life energy, or any combination of the above. If they haven't gone to the equivalent of supernatural medical school, they shouldn't have the requisite knowledge without a very good in-universe explanation (I could buy someone whose parents were medics picking up a lot of knowledge, especially if they were a de facto apprentice).

Finally, a pet peeve: all-healing herbs. They're a cheap fix for one. For another, it kills the realism. It's difficult to believe your Fantasyland forest is populated exclusively by a mysterious plant species which is relatively easy to find, requires no advanced identification skills or special preparation, and cures any random wounds, fevers, or poisonings that occur. Unlike the other problems, this one has an annoying tendency to escape the bounds of Fantasyland and jump over into historical works (yet again, I'm looking at you Sir Walter Scott!). Either put research into it, or have your viewpoint character be totally clueless and knowledge their own lack of botanical first-aid know-how, but don't use the random 'herbs' that fix all plot points.

Published on July 17, 2013 02:01

July 15, 2013

Fixing the Flesh Wounds: Healing & Healers, Part I

It's a dangerous world out there in Fictionland, and characters do have a tendency to get hurt. Interestingly, the first-aid skills of the characters around them and the perception of what is a survivable wound in this setting appears to vary wildly in accordance with the plot. Disposable side characters die instantly from relatively minor illnesses and injuries (or a bit longer and tragically, as the case may be), while lead characters can survive massive trauma with barely a scar (and all of their brain cells and internal organs intact).

It's a dangerous world out there in Fictionland, and characters do have a tendency to get hurt. Interestingly, the first-aid skills of the characters around them and the perception of what is a survivable wound in this setting appears to vary wildly in accordance with the plot. Disposable side characters die instantly from relatively minor illnesses and injuries (or a bit longer and tragically, as the case may be), while lead characters can survive massive trauma with barely a scar (and all of their brain cells and internal organs intact).This can be reasonable if there's a big difference in environments or circumstances-- for example, one character is much closer to medical help, is in a harsher physical environment, has buddies who are good at first aid, or is in a time and place where medical science is largely undeveloped. However, when characters in the same environment have similar diseases or injuries and one shakes it off while the other suffers instant death, it reeks of authorial meddling.

The way to avoid this is to do some comprehensive study of what medical care is like in your setting. What is the level of medical knowledge and ability? Does everyone have access, or is access limited by things like socioeconomic class or location? Which characters, if any, have advanced medical skills? Which characters, if any, have any medical conditions which will effect their care? What in the environment might influence outcomes (temperature, disease-carrying bugs, etc)? Once you've figured this out, you can plausibly have different outcomes for different characters with a solid in-universe explanation.

Finally, it's also worth noting that the rules of the fictional universe should apply to your main characters as well as the minor ones. That means no scrubbing away all consequences of an injury or illness. The character should scar just like everyone else, and not get any special healing perks. Realism will add suspense, as your characters are in genuine danger of harm.

Published on July 15, 2013 01:57

July 12, 2013

The Bartender Event Horizon

Regular blog readers know that one of my pet peeves is characters who either don't seem to work in any appreciable way (and yet are never short of cash at the Obligatory Urban Fantasy Bar) or have one of two or three acceptably 'cool' jobs. One of the issues with this is the lack of people who do jobs that don't fall under 'Acceptably Cool Job' or 'bartender/innkeeper'. For the purposes of this post, I'll call the phenomenon the Bartender Event Horizon, as the entire economy of Urban Fantasyland seems to be taken up with food service and private detectives, and no other sectors, except maybe the stray cab driver, cop, or member of the clergy. One possibility is that you are writing about a dystopian society which has actually reached the Bartender Event Horizon, and everyone is drowning their sorrows together.

Regular blog readers know that one of my pet peeves is characters who either don't seem to work in any appreciable way (and yet are never short of cash at the Obligatory Urban Fantasy Bar) or have one of two or three acceptably 'cool' jobs. One of the issues with this is the lack of people who do jobs that don't fall under 'Acceptably Cool Job' or 'bartender/innkeeper'. For the purposes of this post, I'll call the phenomenon the Bartender Event Horizon, as the entire economy of Urban Fantasyland seems to be taken up with food service and private detectives, and no other sectors, except maybe the stray cab driver, cop, or member of the clergy. One possibility is that you are writing about a dystopian society which has actually reached the Bartender Event Horizon, and everyone is drowning their sorrows together. If you aren't, there's an immediate realism problem. Even if your character has some glamorous job, we should see the workings of the world around them. Presumably your fictional requires thousands of different specialised or semi-specialised professions to make it work (seriously, someone's got to distill all that booze for your troubled private eye to drink), and your character will probably know people who have a wide variety of occupations. If you don't, the audience doesn't really get to see how your fictional society works. Letting the reader see how the ordinary--and extraordinary-- aspects of your setting work is a critical part of moving your story out of generic Urban Fantasyland and into it's own unique world.

Published on July 12, 2013 01:59

July 10, 2013

Jerk Sue

I've mentioned before that apologetically jerkass characters can be compelling for any number of reasons. Sometimes it's refreshing to see an openly selfish character who can serve as a wild card by acting in their own interests; sometimes there's an element of wish fulfillment when the character breaks social rules in a way we secretly wish we could; sometimes the character is simply a fascinating train wreck. A good part of the conflict in all of these cases centres around the fact these characters break the social contract with abandon, and are frequently punished by the other characters or society as a whole.

I've mentioned before that apologetically jerkass characters can be compelling for any number of reasons. Sometimes it's refreshing to see an openly selfish character who can serve as a wild card by acting in their own interests; sometimes there's an element of wish fulfillment when the character breaks social rules in a way we secretly wish we could; sometimes the character is simply a fascinating train wreck. A good part of the conflict in all of these cases centres around the fact these characters break the social contract with abandon, and are frequently punished by the other characters or society as a whole.Then there's Jerk Sue. This character is unrepentantly mean to everyone around them, but is treated with kindness and sympathy by everyone around them. Unlike comedy characters who escape major punishment because their bad behaviour is funny (think Seinfeld), these characters are treated by the narrative as though their antisocial behaviour is totally reasonable, and the characters seem to agree. Showgirls is probably one of the more widely-mocked examples, featuring a main character whom people fall over themselves to befriend her no matter how much she mistreats or ignores them, or how much she responds to everything with bratty tantrums. Again, the issue here isn't her character flaws alone, but the fact the other characters seem utterly oblivious to them.

I think the key is to resist the urge to protect your beloved characters from the consequences of their actions. Let them mess up, and more importantly, let them feel the full effects of their bad behaviour. It's tempting to coddle our characters, since we know so much about their inner life and possibly identify with them (sometimes in the form of letting the character be a jerk with impunity as a wish-fulfillment fantasy), but it's a sure way to lose the empathy of your audience.

Published on July 10, 2013 02:33

July 8, 2013

Mentor Job Hazards

Forget logging or fishing or coal-mining-- in Fantasyland, Wise Old Mentors have the highest death rate among pretty much any profession except the Dark Lord's bodyguards.

Now, the mentor is a key figure from the Hero's Journey plot archtype, and it also makes sense on a metaphorical level for the character to die. After all, the hero needs to continue on alone without the mentor to bail them out of trouble. Symbolically, it's also the transfer of responsibility to the next generation, the future supplanting the past.

That said, this archetype has turned into a cliche plot device, where the mentor exists to tell the main character how special they are, give them instant training in their special skill, and then die to provide angst and a possible revenge plot. Instead of any significant symbolism, they're a walking info dump in an Alec Guinness skinsuit.

If you are using the Hero's Journey as a template, that's one thing. But if your mentor is nothing more than a walking, talking Wikipedia page on the main character's backstory or special abilities or quest goals, you might consider another means to get that information across. Better still, revising the methods for delivering info can mean major changes to the plot, and get rid of some of the more annoying cliches in fantasy. For example, why not have the character's parents train them to use their gift? What about having a gift that's not unique, and having to sit though 'using fire magic without causing horrible destruction' classes in school, the way lots of us had to sit though Home Ec/Health? Even a long-term relationship with the mentor-- maybe is a relative who shares their talent, or a respected community member who regularly takes on students-- is much more interesting than having someone who swoops in to do a round of improbably fast teaching and then kick the bucket.

Published on July 08, 2013 00:26

July 5, 2013

Miserable Mixed Characters: Sexytimes With the Other, Part III

Assuming the couple from the past two posts gets down to humping (rather than longing looks and maybe some handholding), the result may be a mixed-race kid. I say mixed-race because it's the only variant of this trope I've seen played out in a prescribed way, perhaps because of the obsession with race in American culture and the prevalence of US media.

The mixed-race character follows one of two types. First is the 'blink-and-you-miss-it' mixed heritage, which is common in urban fantasy heroines. Their background is brought up once or twice to give them 'cred' about some issue, establish them as a cool outsider, and maybe stir up some conflict with another character, conveniently establishing that character as the designated bad guy. The heroine's identity doesn't get explored, or if it does the exploration is dropped or doesn't go beyond the maladjusted stereotype described below.

The more common version is the Multiracial and Maladjusted in which the character is treated poorly by both sides of the family due to their heritage, and also outcast by society. This is so common, particularly in American works, that the trope even has it's own Wikipedia page. In older stories, or stories set in an earlier era, the conflict is mostly external. More modern works like to play up the identity-related angst. But the bottom line is that the character is not shown to be well-adjusted and accepted by both cultures.

There's a lot to explore when you're writing multiracial characters, so you're cheating both the story and the audience by wearing down the same old grooves instead of exploring this particular character's life. Show how they integrate their mixed heritage, or how they feel if they identify with one more than the other. Maybe it's a non-issue in some situations and a problem in others. Maybe their siblings have a different perspective. Let the complexity build, and you'll get a much more interesting character.

The mixed-race character follows one of two types. First is the 'blink-and-you-miss-it' mixed heritage, which is common in urban fantasy heroines. Their background is brought up once or twice to give them 'cred' about some issue, establish them as a cool outsider, and maybe stir up some conflict with another character, conveniently establishing that character as the designated bad guy. The heroine's identity doesn't get explored, or if it does the exploration is dropped or doesn't go beyond the maladjusted stereotype described below.

The more common version is the Multiracial and Maladjusted in which the character is treated poorly by both sides of the family due to their heritage, and also outcast by society. This is so common, particularly in American works, that the trope even has it's own Wikipedia page. In older stories, or stories set in an earlier era, the conflict is mostly external. More modern works like to play up the identity-related angst. But the bottom line is that the character is not shown to be well-adjusted and accepted by both cultures.

There's a lot to explore when you're writing multiracial characters, so you're cheating both the story and the audience by wearing down the same old grooves instead of exploring this particular character's life. Show how they integrate their mixed heritage, or how they feel if they identify with one more than the other. Maybe it's a non-issue in some situations and a problem in others. Maybe their siblings have a different perspective. Let the complexity build, and you'll get a much more interesting character.

Published on July 05, 2013 02:17