S.B. Stewart-Laing's Blog, page 15

September 11, 2013

Editing Historical Figures

Writing about real people is tricky. First of all, people are complicated, and historical figures often don't conform to modern morality, so there's a great temptation to 'upgrade' them into an acceptable character. Second, there can be major information gaps: we may know little about someone's emotional life, their personal relationships, or even their childhood and general background.

Writing about real people is tricky. First of all, people are complicated, and historical figures often don't conform to modern morality, so there's a great temptation to 'upgrade' them into an acceptable character. Second, there can be major information gaps: we may know little about someone's emotional life, their personal relationships, or even their childhood and general background.That said, certain seemingly innocuous edits can carry a lot of meaning. The biggest ones, in my opinion, are age, ethnicity/race, and social class. The issue with these alterations is that although they do not result in the author explicitly changing the character's motivation, these elements will fundamentally change how the character views and interacts with their world. This is also a location where Unfortunate Implications love to lurk. (I would rant about Randall Wallace here, but the Nostalgia Critic has already laid into everything that's wrong with the revisionist history fest that is Pearl Harbor. You can watch the video here).

The optimist in me wonders if some of these revisions spring from innocent intentions-- either we overtly want to make a character more like us, or more 'relateable to the hypothetical audience, or we have some deep-seated cultural misunderstanding that causes us to misread the character's motives, or we are clueless about the person's inner life.

The first is a natural instinct, and one you have to resist, or risk peopling everything you write with an army of your clones. Unless that is actually your premise, or you are actually the Master, this is something to avoid. Focus on making your characters realistically complex and uniquely recognisable as themselves, and your readers will be interested. The second is an invitation to really educate yourself about your setting-- not just the facts and date, but what deep-seated values underpinned the culture, what beliefs were considered irrefutable fact and which were being actively questioned.

The case of the last is trickier. In many cases, we have to imagine the historical figure's inner life with only a small amount of context. However, we can guess many of the specifics by doing research about the time period. Even if that particular person didn't record their thoughts, we can learn about the beliefs and attitudes and typical experiences of the time and construct a life story that fits into that world, rather than importing modern sensibilities into another era. Finally, you have no excuses if you actually can find out what your historical character was thinking-- for example, if they wrote reams of letters or kept a diary or lived within the past 50-odd years.

Published on September 11, 2013 02:58

September 9, 2013

Hate the Player, Not the Genre; Or What the World of Darkness Taught Me About Urban Fantasy

A lot of people are surprised that I actually enjoy the Classic World of Darkness games, because bluntly, the franchise might as well be called Ethnic Stereotypes'R'Us (they periodically forget that Africa exists, except for Egypt-- whether this is a insult or a lucky dodge, I'm not sure). Especially in some of the earlier editions, the level of not doing the research and appropriating mythology willy-nilly is pretty impressive.

A lot of people are surprised that I actually enjoy the Classic World of Darkness games, because bluntly, the franchise might as well be called Ethnic Stereotypes'R'Us (they periodically forget that Africa exists, except for Egypt-- whether this is a insult or a lucky dodge, I'm not sure). Especially in some of the earlier editions, the level of not doing the research and appropriating mythology willy-nilly is pretty impressive.Here's the key: the games are what you make of them. You can merrily throw out all the suggestions about what you're 'supposed' to do with your stories and characters while maintaining the basic setting and mechanics. The facepalm-inducing commentary on the character types is part of the game creators' interpretation of their world, but it isn't in any way integral to the game itself, or even to the setting.

Unfortunately, many writers take the Urban Fantasy Template World very much at face value. I've cited the World of Darkness games because they have had a direct influence on creating that template. There is an expectation that writing urban fantasy means using that set of supernatural creatures, that gothic-punk aesthetic (complete with the Standard Urban Fantasy Dress Code), that same selection of suggested investigation-and-mayhem-for-hire jobs, and that same narrow and heavily stereotyped selection of character backgrounds.

But it's just that-- conventions and cliches. Urban fantasy is whatever you make it. As a speculative fiction author, it's up to you to build your own world, which can be as wildly creative as you wish.

Published on September 09, 2013 07:28

September 6, 2013

Villain Flaws

Like the heroes, the villains should have well-developed flaws, often ones which will lead to their downfall. Unfortunately, the usual go-to flaw is 'insanity' or some variant thereof, which is used as both the explanation the villain's consistently contrived bad decisions and the motive behind their empty 'mwahahaha!' style evildoing. Now, setting aside the huge problem of conflating 'insane' with 'evil and dangerous', it's simply not an interesting motive. Furthermore, it gives the hero a cheap method for defeating the antagonist-- they merely have to make use of the villain's illogical decisions, or take advantage of the fact the villain has zero grip on reality.

Like the heroes, the villains should have well-developed flaws, often ones which will lead to their downfall. Unfortunately, the usual go-to flaw is 'insanity' or some variant thereof, which is used as both the explanation the villain's consistently contrived bad decisions and the motive behind their empty 'mwahahaha!' style evildoing. Now, setting aside the huge problem of conflating 'insane' with 'evil and dangerous', it's simply not an interesting motive. Furthermore, it gives the hero a cheap method for defeating the antagonist-- they merely have to make use of the villain's illogical decisions, or take advantage of the fact the villain has zero grip on reality.A true character flaw, however, presents both motive and challenges for the protagonist. It's even better if the flaw is a trait which could have been a force for good in other circumstances. The antagonist is now human, and is also free to be as competent as possible. Instead of waiting for the villain to trip over their own feet, the hero has to not only discover the antagonist's shortfalls, but be clever and innovative enough to exploit them.

Published on September 06, 2013 02:33

September 4, 2013

Weighting the Dice

'...But if you think something is bullshit, the answer is not more bullshit.'

--Amanda Mannen

All fiction, to some degree, is message fiction. Our beliefs inform which values, actions, and outcomes we see as positive or negative or ambiguous, and these views become an integral part of our plot, setting, and characters.

Some fiction, however, explicitly engages issues instead of folding them into the background. Because fiction is such a wonderful medium for prompting discussion, I tend to think this is a good thing. Fiction-- particularly speculative fiction-- allows us to look at real-life problems with a fresh perspective, and to give us the safety of distance to formulate our thoughts without the baggage of past and current events. And a speculative fiction world can often allow us to explore the implications of an idea more fully or more clearly than we can when writing about real life.

That said, there is a difference between creating an area where you can run your thought experiment, and creating a world in which all of your ideas are unequivocally true so that they can be proven via a rigged plot setup; the first asks a question, the second is all about answering one. For example, it's one thing to write a novel (or make a film) about aliens immigrating to Earth and struggling over resources and culture with humans, and quite another to write the same story in which every single one of the aliens is irredeemably evil.

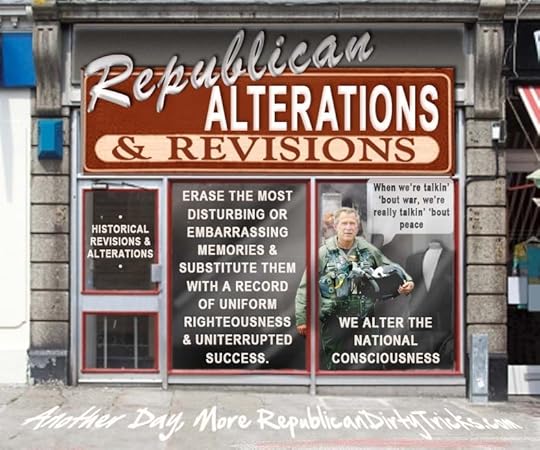

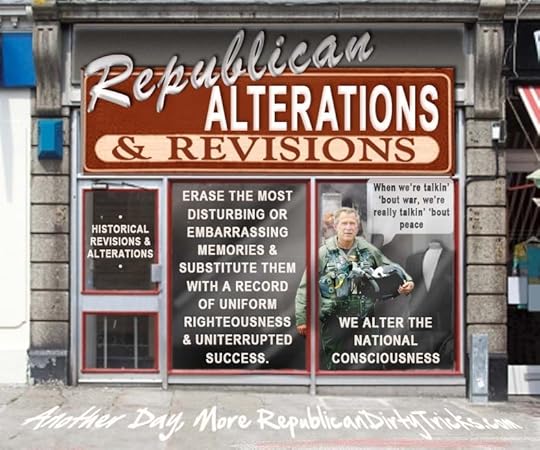

I'd also like to make a special note here for the revisionist historians. It's one thing to fill in the gaps in our historical knowledge with educated guesses, but quite another to make things up to serve your agenda, or worse, edit known facts to better suit your views. As I've said before, how we present history is important, and we have a level of responsibility when presenting anything as fact.

I think message fiction is most powerful when it allows readers to draw their own conclusions, rather than rigging the whole thing by ensuring there is an objectively 'right' answer.

--Amanda Mannen

All fiction, to some degree, is message fiction. Our beliefs inform which values, actions, and outcomes we see as positive or negative or ambiguous, and these views become an integral part of our plot, setting, and characters.

Some fiction, however, explicitly engages issues instead of folding them into the background. Because fiction is such a wonderful medium for prompting discussion, I tend to think this is a good thing. Fiction-- particularly speculative fiction-- allows us to look at real-life problems with a fresh perspective, and to give us the safety of distance to formulate our thoughts without the baggage of past and current events. And a speculative fiction world can often allow us to explore the implications of an idea more fully or more clearly than we can when writing about real life.

That said, there is a difference between creating an area where you can run your thought experiment, and creating a world in which all of your ideas are unequivocally true so that they can be proven via a rigged plot setup; the first asks a question, the second is all about answering one. For example, it's one thing to write a novel (or make a film) about aliens immigrating to Earth and struggling over resources and culture with humans, and quite another to write the same story in which every single one of the aliens is irredeemably evil.

I'd also like to make a special note here for the revisionist historians. It's one thing to fill in the gaps in our historical knowledge with educated guesses, but quite another to make things up to serve your agenda, or worse, edit known facts to better suit your views. As I've said before, how we present history is important, and we have a level of responsibility when presenting anything as fact.

I think message fiction is most powerful when it allows readers to draw their own conclusions, rather than rigging the whole thing by ensuring there is an objectively 'right' answer.

Published on September 04, 2013 01:49

September 2, 2013

And Now For Something Completely Different: 'VGHS', Indie Publishing and Non-Mainstream Voices

I was recently introduced by the Lady Friend to a YouTube series entitled Video Game High School (VGHS). On one level, it's an affectionate parody of both geek culture and of formulaic high school dramas. On another, it has a much more realistic representation of actual high school students in terms of race and gender distribution than most high school dramas. It happily ignores a zillion annoying race and gender tropes-- the characters are themselves, rather than being 'the girl gamer' or 'the Asian guy'-- which is helped by the fact there are multiple representatives of various groups around.

I was recently introduced by the Lady Friend to a YouTube series entitled Video Game High School (VGHS). On one level, it's an affectionate parody of both geek culture and of formulaic high school dramas. On another, it has a much more realistic representation of actual high school students in terms of race and gender distribution than most high school dramas. It happily ignores a zillion annoying race and gender tropes-- the characters are themselves, rather than being 'the girl gamer' or 'the Asian guy'-- which is helped by the fact there are multiple representatives of various groups around.In a world where a studio refused to greenlight a fantasy-action movie because it stars a woman, and all kinds of racist rubbish does get the go-ahead for production, VGHS is an example of how indie productions can bring a fresh perspective when the industry is disproportionately white, wealthy, heterosexual and male (and over 35). And it's not just YouTube: Netflix-sponsored series have also done a good job of bringing in more diverse, interesting casts. Notably Orange is the New Black has earned well-deserved praise for its portrayals of LBGT folks, people of colour, and people of a variety of social classes.

It's not just movies and TV that can benefit by indie work shaking things up: the publishing industry in the west is disproportionately white, male, and upper-class, and it shows in everything from the novels that are accepted to the way material is presented (most noticeably 'whitewashing' of book covers). Independent publishing can serve as a platform for authors whose work brings in another perspective. Given the pattern emerging with TV shows, I'm optimistic that the rise of indie publishing will mean not just more books, but a greater variety of good stories about a greater variety of interesting, relevant characters.

Published on September 02, 2013 02:42

August 30, 2013

Multiple Identity Syndrome: Writing Someone Else's Oppression, Part II

A thoughtful recent post on Everyday Feminism pointed out the problem of people getting bristly when told they are privileged. Personally, if I had a pound for every time I've run across a 'I'm white and I'm not privileged: I was the victim of anti-gay hate crimes/grew up dirt-poor/am disabled and I worked for everything I have' post in response to a discussion of white privilege, I'd probably be able to swim in a giant money pit like Scrooge McDuck.

A thoughtful recent post on Everyday Feminism pointed out the problem of people getting bristly when told they are privileged. Personally, if I had a pound for every time I've run across a 'I'm white and I'm not privileged: I was the victim of anti-gay hate crimes/grew up dirt-poor/am disabled and I worked for everything I have' post in response to a discussion of white privilege, I'd probably be able to swim in a giant money pit like Scrooge McDuck.The reason for these posts isn't precisely 'ignorance', nor is it necessarily a one-sided communication failure: we've got one side being defensive and refusing to listen, and another which can sometimes come off as implying that 'having privilege' means 'if you are able-bodied/wealthy/male/whatever, your life is perfect and you do not understand adversity'.

Rather, it's something more complex-- the interaction of multiple identities and areas of privilege and oppression throughout our society. The article I cited above doesn't really delve into the idea that having identity privilege in one area doesn't mean having it in another. For example, a straight, black man in the United States would experience 'straight privilege' from his sexual orientation, since he operates a world that assumes he's heterosexual and affirms his romantic relationships; however, he can simultaneously experience racial oppression when surrounded by a dominant culture which codes his behaviour 'threatening' or 'suspicious' even if he's just popping into the grocery store. At the same time, we can have a white man with a mental illness, who may have white privilege in some circumstances--for example, he might not been seen as a potential shoplifter and harassed by store staff-- but he's actually even more likely than the neurotypical black guy in the previous example to be the victim of a violent hate crime.

Those are just two examples, which don't even delve into individual life stories. So when you're thinking about a character, it's a trap to imagine only one facet of their identity as meaning they must by default have everything sorted out. Think of them as a whole, with multiple layers of identity which influence how they interact with society and ingrained systems of oppression.

Published on August 30, 2013 01:44

August 28, 2013

This Thing Is Not Like The Other: Writing Someone Else's Oppression, Part 1

A while ago, I ran across a discussion on Twitter about how we write people who aren't like us. It's something writers have to do constantly, hence the title of this blog. However, the discussion in question veered off into an interesting direction: people of all different backgrounds discussed expressing confidence in their ability to write about a marginalised group to which they did not belong based on their own experiences as the member of a different marginalised group.

Now, while there can certainly be overlaps, I'm not sure how transferable these experiences really are on a large scale. Even within a group, people will have very different experiences-- for example, people with invisible disabilities experience different manifestations of abilism than people whose conditions are immediately apparent.

Although we tend to think of privilege and oppression in very delineated terms, there are many facets to how a marginalised group interacts with the majority. Here are a few:

Why is this group marginalised in your setting? (Were they imported as slaves, were they an indigenous people who were conquored, are they a religious minority who go against the established belief system, do people see this group as a burden or a threat, etc)How long has this been going on?How easy is it to hide one's marginalised status? Can one leave the marginalised group, and if so how?

When answering these questions, one can see how much someone's experience is a product of their specific context and identity. Even if we're writing about our own 'in group', I think it's better to err on the side of research and gathering people's stories and experiences, rather than assuming we know all the answers.

Now, while there can certainly be overlaps, I'm not sure how transferable these experiences really are on a large scale. Even within a group, people will have very different experiences-- for example, people with invisible disabilities experience different manifestations of abilism than people whose conditions are immediately apparent.

Although we tend to think of privilege and oppression in very delineated terms, there are many facets to how a marginalised group interacts with the majority. Here are a few:

Why is this group marginalised in your setting? (Were they imported as slaves, were they an indigenous people who were conquored, are they a religious minority who go against the established belief system, do people see this group as a burden or a threat, etc)How long has this been going on?How easy is it to hide one's marginalised status? Can one leave the marginalised group, and if so how?

When answering these questions, one can see how much someone's experience is a product of their specific context and identity. Even if we're writing about our own 'in group', I think it's better to err on the side of research and gathering people's stories and experiences, rather than assuming we know all the answers.

Published on August 28, 2013 02:36

August 26, 2013

When the Facts Aren't Fair and Balanced

'Sometimes, uncomfortably aware that the antagonist is turning into a caricature, the author tries to "round him out" by giving him a good side...Adolf introduces Fascism to Germany, spreads war throughout Europe, murders millions in concentration camps-- but he's a strict vegetarian and loves his dog. Tossing in a touching scene with his German shepherd and a dish of lentils won't make Hitler's character "balanced". Hitler's character isn't balanced.'

'Sometimes, uncomfortably aware that the antagonist is turning into a caricature, the author tries to "round him out" by giving him a good side...Adolf introduces Fascism to Germany, spreads war throughout Europe, murders millions in concentration camps-- but he's a strict vegetarian and loves his dog. Tossing in a touching scene with his German shepherd and a dish of lentils won't make Hitler's character "balanced". Hitler's character isn't balanced.'--How Not to Write a Novel

There's a tendency for some historical fiction writers to go for a 'good guys vs bad guys' angle, which often fails in the face of history's nuances, which I've written about before. Today, I'll talk about the authors who feel compelled to make everything ambiguous, because that makes it 'real'. Again, real life isn't quite so dramatically simple. There's a difference between being neutral, being sensitive to context, and creating 'gray and gray morality' where none exists.

Perhaps this is part of the idea that being objective about an issue means treating both sides as equally valid, and that history should be written about in a 'fair and balanced' way. But there are more than enough circumstances where the facts are not 'fair and balanced'. Someone--or a group of someones-- did something that's awesomely heroic or downright despicable. It's one thing to use neutral language to convey facts (sometimes it can be used for incredibly chilling effect) but another to alter the facts or context to create a more 'balanced' narrative.

Another part of the problem may be a confusion between explaining what motivates the characters and excusing their actions. We need motivations for the characters to be believable. Otherwise they're just cardboard heroes and villains. But because they have a reason that makes sense to them doesn't mean the author has to make excuses for them or show tacit approval. We can understand that the bad guy sincerely believes it's okay to buy and sell human beings and has overcome any niggling morality with a bout of mental gymnastics, even if we see his actions as horrifying and inexcusable.

In the end, it's important to convey correct information (or well-researched alternate history timelines) rather than trying to pretend that everyone is morally ambiguous all of the time. Larger-than-life struggles between heroes and villains, between good and evil, sometimes happen, and we need to tell those stories too.

Published on August 26, 2013 02:22

August 23, 2013

Put Some Clothes On!

Maybe because I've spent a good chunk of my life working in jobs with dress codes, but I get rather put off when I crack open an urban fantasy novel and see a bunch of characters wearing the Standard Urban Fantasy Sexywear.

Maybe because I've spent a good chunk of my life working in jobs with dress codes, but I get rather put off when I crack open an urban fantasy novel and see a bunch of characters wearing the Standard Urban Fantasy Sexywear.Now, because everyone in these novels is ridiculously attractive, they can presumably make the clubwear look good. But it doesn't address my nagging issue: no one dresses like that for work, and for good reason.

Let's look at some of the staples: High heels make it difficult to walk on rough surfaces, let alone run. They're prone to breaking, getting caught on things, and skidding out from under one's centre of mass, thus causing all manner of knee and ankle injuries. Leather trousers, particularly the skin-tight variety that seems to be all the rage in Urban Fantasyland City, are relatively restrictive if you want to run or scamper over things, and also get hot and sweaty (in the smelly gym sock way, not the sexy way). Slinky cocktail dresses are prone to causing wardrobe malfunctions outside of their natural habitat. Trench coats, while good for commuters who want to ward off puddle splashes, are warm and bulky, which is not ideal for running around (double if it's leather). Also, no one ever seems to get the belt of said trench coat caught in fences, snagged by the bad guy or, worst of all, dropped into the toilet. Also, all of the above are expensive. If one is going to chase urban fantasy criminals and regularly get splattered with supernatural critter blood, it seems like a poor choice to wear nice partywear. I really want to see someone who goes the pragmatic route and dresses like a construction worker.

Alternately, you could have an urban fantasy protagonist who is (*gasp*) not a private detective or in food service, and has a job at which one either wears a uniform, or a works a job which has a respectable dress code (meaning that dressing like a Goth version of Courtney Stodden won't fly!). Personally, I favour this last option-- we need more job diversity in urban fantasy. That and practical clothes.

Published on August 23, 2013 01:32

August 21, 2013

Natural Talent: Mary Sue and the Entitlement Problem, Part II

As I said on Monday, a lot of Mary Sue characters on their self-actualisation mission have a special talent. There's nothing inherently wrong with this-- everyone has unique skills, passions, and ways of seeing the world differently. However, there's a big difference between a 'busting their behinds to make it' plot where the talented character has to train and practice to overcome obstacles and take on the competition, and a 'acknowledge my mad skillz' plot, where the character is super talented with no major visible effort, and the main conflict is overcoming the haters.

As I said on Monday, a lot of Mary Sue characters on their self-actualisation mission have a special talent. There's nothing inherently wrong with this-- everyone has unique skills, passions, and ways of seeing the world differently. However, there's a big difference between a 'busting their behinds to make it' plot where the talented character has to train and practice to overcome obstacles and take on the competition, and a 'acknowledge my mad skillz' plot, where the character is super talented with no major visible effort, and the main conflict is overcoming the haters. There are several major problems with this plot. First of all, the character does nothing to earn their awesomeness, and yet the reader and the other characters are supposed to accept them as special. In many cases, the character is all talk (or all authorial editorialising), and not a whole lot of behaviour that backs up the assertion they are a magical unique snowflake.

Second, the plot runs on the idea that 'talent' is some inborn trait that runs on self-confidence, rather than being the product of hard work. Now, some people have particular talents or interests from a young age, but in the real world 'natural' talent will only carry you so far. Talented folks have to work their butts off just like everyone else to be successful in their field-- the usual rule being 10,000 hours of intense, meaningful practice to truly master a skill at a high level. It's insulting (not to mention absurdly unrealistic) to have a 'talented' character breeze in with no real practice and do better than people who have been in the game for years. But in the end, it's the idea that some people are just inherently better than others, and should be fawned over and should not have to work for their success.

I should point out this plot is different from the 'misfit wants to pursue their passion' plot, a la Billy Elliot, because those plots usually include the character not only resisting the doubters, but working up a storm to do the one thing that gets them up in the morning. Seeing a character work and struggle and earn their success in spite of being told they'll fail-- now that's inspiring.

Published on August 21, 2013 01:13