S.B. Stewart-Laing's Blog, page 13

November 29, 2013

Incredible Journeys

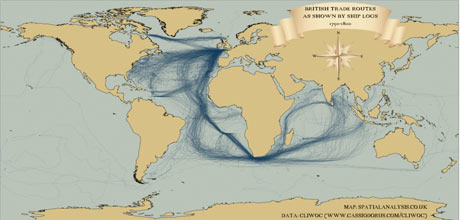

Humans can sometimes be rather insular creatures. Particularly in the days before quick long-distance travel by planes, trains, and automobiles*, people could easily spend their whole lives within a small geographic area. For many areas of Fantasyland, the lack of reliable long-distance transport seems to be the mechanism responsible for the incredibly homogenous cultures (and often, in European-inspired settings, the lack of brown folks).

Humans can sometimes be rather insular creatures. Particularly in the days before quick long-distance travel by planes, trains, and automobiles*, people could easily spend their whole lives within a small geographic area. For many areas of Fantasyland, the lack of reliable long-distance transport seems to be the mechanism responsible for the incredibly homogenous cultures (and often, in European-inspired settings, the lack of brown folks).While this can be realistic-- particularly in geographically hard-to-reach areas, such as the Hawaiian islands or the Dolomite region of the Swiss Alps-- we tend to underestimate the determination of humans to explore and travel and hunt for valuable resources without high-tech aid. The Silk Route was established almost 2,500 years ago, with traders traversing two continents east to west to exchange goods. Almost a millennium before that, humans travelled from the boot of Italy to Scandinavia to trade amber. Africa and the Americas were likewise crisscrossed with complex travel routes by sailboat, canoe, foot, llama and dogsled.

These travellers weren't just there one day and gone the next. Personal relationships, romance, and cultural exchange are part and parcel of a trade relationship, particularly where both societies are on fairly even footing. Historically, the children of cross-cultural unions have served as liaisons between the two groups. Unfortunately, all kinds of pathogens tag along as well, and in a society without germ theory, this is extremely difficult to contain. Depending on the disease, and whether the population carries any natural immunity, this can result in anything from a nuisance to a full-blown epidemic.

In building your fantasy world, think about how and why people travel. And even if your world is low-tech, don't rule out long-distance journeys. Once you've figured this out, think about what it means-- the cultural mixing, the trade goods, the formation of group identities, the spread of diseases. Even if you don't develop it as major storyline (although there's many, many cool stories to be told there!), it will give your world some depth and a the sense of scale that marks great fantasy worldbuilding.

*Long ocean journeys weren't particularly safe or speedy

Published on November 29, 2013 02:18

November 27, 2013

Making the Villain's Downfall Count

As I've said before, there is no villainous downfall so satisfying as a well-aimed karmic death. Due to our nature as intelligent, social mammals*, we're hard-wired to feel satisfaction when someone is punished for harming the rest of the group, particularly when their actions directly cause their demise.

With that in mind, there are a few guidelines to making a karmic defeat meaningful in the story. First, the punishment needs to scale to the most heinous crime the villain has committed. If they've committed the trifecta of murder, arson and jaywalking, we're not going to be satisfied with a traffic ticket.

Second, the punishment has to be directly related to the worst evil deed. The one exception to this is when the seemingly minor consequence of a smaller offense triggers a chain reaction. For example, one episode of My Name is Earl featured a fast-food restaurant manager who mistreats his employees, cheats on his wife, and embezzles from the company. When Earl punches him after a fairly minor bit of jerkass behaviour involving a balloon animal, he ends up in the hospital...where the wife and the girlfriend meet each other, the wife finds out about his shady financial dealings when she files for divorce...and everything falls down around his ears. However, a key component is still causality-- had the manager been felled by a random event rather than a result of his selfish behaviour, it wouldn't be particularly satisfying.

One of the reasons I got so, so annoyed with the ending of In The Flesh was that it violates the proximity expectation. As soon as the villain kills Rick-- his own son-- we need to see him punished as a consequence of that shocking act. Instead, he is bumped off by a minor character as revenge for killing that character's zombified wife, and there are absolutely no consequences for murdering Rick except that the main character yells at him**.

Again, there must be a causal link-- on both a practical and a moral level-- to the villain's downfall to make it a truly satisfying moment of fictional justice.

*Other social mammals, such as wolves, dolphins and monkeys, have an acute sense of justice and will act quickly and forcefully to punish anti-social behaviour.

**There is a massive homophobic thread to the whole thing, which is it's own rant.

With that in mind, there are a few guidelines to making a karmic defeat meaningful in the story. First, the punishment needs to scale to the most heinous crime the villain has committed. If they've committed the trifecta of murder, arson and jaywalking, we're not going to be satisfied with a traffic ticket.

Second, the punishment has to be directly related to the worst evil deed. The one exception to this is when the seemingly minor consequence of a smaller offense triggers a chain reaction. For example, one episode of My Name is Earl featured a fast-food restaurant manager who mistreats his employees, cheats on his wife, and embezzles from the company. When Earl punches him after a fairly minor bit of jerkass behaviour involving a balloon animal, he ends up in the hospital...where the wife and the girlfriend meet each other, the wife finds out about his shady financial dealings when she files for divorce...and everything falls down around his ears. However, a key component is still causality-- had the manager been felled by a random event rather than a result of his selfish behaviour, it wouldn't be particularly satisfying.

One of the reasons I got so, so annoyed with the ending of In The Flesh was that it violates the proximity expectation. As soon as the villain kills Rick-- his own son-- we need to see him punished as a consequence of that shocking act. Instead, he is bumped off by a minor character as revenge for killing that character's zombified wife, and there are absolutely no consequences for murdering Rick except that the main character yells at him**.

Again, there must be a causal link-- on both a practical and a moral level-- to the villain's downfall to make it a truly satisfying moment of fictional justice.

*Other social mammals, such as wolves, dolphins and monkeys, have an acute sense of justice and will act quickly and forcefully to punish anti-social behaviour.

**There is a massive homophobic thread to the whole thing, which is it's own rant.

Published on November 27, 2013 02:26

November 25, 2013

Play-Dough

I'd be willing to guess that many of you lovely readers who grew up in a western country played with Play-Dough as kids. A number of you are probably recalling the distinctive smell and the slightly stiff squishyness under your fingers as you read this. One of the great things about Play-Dough is that it stays malleable, and can be sculpted and re-sculpted into anything you want. You can embellish and remove, squash and reshape, or just put it all back in the jar for later.

I'd be willing to guess that many of you lovely readers who grew up in a western country played with Play-Dough as kids. A number of you are probably recalling the distinctive smell and the slightly stiff squishyness under your fingers as you read this. One of the great things about Play-Dough is that it stays malleable, and can be sculpted and re-sculpted into anything you want. You can embellish and remove, squash and reshape, or just put it all back in the jar for later.The writing process is, in many ways, like breaking out a big ball of Play-Dough. First of all, nothing you write is set in stone until you've published or the play is on stage or the final edit of the film is made (and even then, story elements can be given alternate explanations in sequels). You are working with a medium which makes encourages revision during the work process. Parts of the story can be cut, moved around, manipulated into a totally different form, or added as you need, all without necessitating a total do-over. Using that flexibility to its fullest allows you to explore different ideas-- if it doesn't work, it can be changed.

Second, a story, or any chunks of writing which you particularly like, can be set aside for later. It's a lot easier to cut a favourite scene that's just not working in your story if know you can put it 'back in the jar' and retrieve it when you're ready to work on it again, or have found it a home in another story. These pieces may be art, but they're also the raw building material of something larger: the story. Remember they can be moved around, removed, and put away for later revision if that's what serves the work.

Finally, thinking about your work as 'Play-Dough' rather than some intricate work in marble allows you to relax and have fun telling a story. It's much more pleasant to work that way. Plus it allows you to be surprised by your own creativity and emotional experiences as you write.

Published on November 25, 2013 01:30

November 22, 2013

Can We Use Our Words, Please?

Almost all of us can recall being in a dustup as a kid. When an adult intervened, we got admonished for hitting each other (or throwing sand, or pulling hair) and told to 'work it out' or 'use our words'. Although I can't speak for every single culture, there is a fairly universal need for people to learn at a young age to resolve disputes without having fights in public. Even societies which allow for conflict resolution by violence tend to do so in a carefully prescribed way, rather than flailing at each other willy-nilly every time someone annoys someone else.

Almost all of us can recall being in a dustup as a kid. When an adult intervened, we got admonished for hitting each other (or throwing sand, or pulling hair) and told to 'work it out' or 'use our words'. Although I can't speak for every single culture, there is a fairly universal need for people to learn at a young age to resolve disputes without having fights in public. Even societies which allow for conflict resolution by violence tend to do so in a carefully prescribed way, rather than flailing at each other willy-nilly every time someone annoys someone else.The denizens of Fantasyland (and to a lesser extent Urban Fantasy City) seem to have significantly less qualms about disrupting their routine to kick some ass. Obviously, some of this is a necessary deviation from reality-- after all, listening to people who aren't even real argue in circles is about half a step above watching paint dry in terms of entertainment value. That said, there are all kinds of ways to create interesting conflict without having characters constantly kicking the crap out of each other.

Part of the problem, I think, is the conflation of 'strong characters' with physical aggression. This is particularly true of female characters, who often get accused of being wimpy Victorian stereotypes if they're not curb-stomping a monster every other minute. Meanwhile, menfolk are being held to the strict standards of masculinity as a function of how much butt they can kick. Male characters who deviate from this are coded as wimps, and either become more athletic and aggressive, or become a permanent punchline.

While some liberty has to be taken (for example, people will often rehash arguments many times before the conflict moves forward, which doesn't work in fiction), it's a good idea to think about the many forms a conflict can take. In some cases, much of the tension can even be driven by the characters' internal monologues. And also think about the myriad problem-solving strategies that don't involve beating the antagonist into a pulp.

Published on November 22, 2013 02:03

November 20, 2013

Cynic Has a Point: Attack of the GrimDark, Part II

In real life, bad things happen. They happen to good people and bad people, to people who appear to be getting their karmic due and to innocent bystanders. And since the beginning of human history, storytelling has been a way for us to collectively process these events.

In that way, truly dark fiction-- particularly speculative fiction-- has a place in our collective psyche. Confronting the worst, most terrifying parts of our collective and individual human experience in fiction is part of understanding them. For example, I think the large amount of fiction of all genres set in WWII* (or an alternate history version) is a manifestation of our society trying to understand and process that scale of destruction and suffering.

As I have written before, this is also true of YA. While fiction which is dark for the sake of being perceived as 'cool' or 'edgy' lacks merit on this front, that's because it tends to come from a place of emotional ignorance and insincerity, rather than because of the material itself. When the author writes with genuine understanding and insight, dark stories can be particularly valuable for young readers who may feel isolated by their problems. Speculative fiction, once again, is a safe area, just detached enough from the immediate situation to allow thinking, but applicable enough to offer insight into the real world.

Finally, I would like to point out that portraying awful things in fiction does not mean condoning them, even if the characters believe they're doing the right thing. You have hundreds of ways to show the consequences of an action, even if your fictional society is blind to them. In some ways, it is more powerful to portray the fallout without commentary rather than hosting an authorial PSA via your characters.

*Although one cannot discount the appeal of a ready-made outrageously evil villain.

In that way, truly dark fiction-- particularly speculative fiction-- has a place in our collective psyche. Confronting the worst, most terrifying parts of our collective and individual human experience in fiction is part of understanding them. For example, I think the large amount of fiction of all genres set in WWII* (or an alternate history version) is a manifestation of our society trying to understand and process that scale of destruction and suffering.

As I have written before, this is also true of YA. While fiction which is dark for the sake of being perceived as 'cool' or 'edgy' lacks merit on this front, that's because it tends to come from a place of emotional ignorance and insincerity, rather than because of the material itself. When the author writes with genuine understanding and insight, dark stories can be particularly valuable for young readers who may feel isolated by their problems. Speculative fiction, once again, is a safe area, just detached enough from the immediate situation to allow thinking, but applicable enough to offer insight into the real world.

Finally, I would like to point out that portraying awful things in fiction does not mean condoning them, even if the characters believe they're doing the right thing. You have hundreds of ways to show the consequences of an action, even if your fictional society is blind to them. In some ways, it is more powerful to portray the fallout without commentary rather than hosting an authorial PSA via your characters.

*Although one cannot discount the appeal of a ready-made outrageously evil villain.

Published on November 20, 2013 02:24

November 18, 2013

Darker & Edgier: Attack of the GrimDark, Part I

'The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist: a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain.'

'The trouble is that we have a bad habit, encouraged by pedants and sophisticates, of considering happiness as something rather stupid. Only pain is intellectual, only evil interesting. This is the treason of the artist: a refusal to admit the banality of evil and the terrible boredom of pain.'— Ursula K. Le Guin

In the absence of actual traumatic events, I think most kids hit a point--usually around puberty-- where dark, depressing, 'edgy' stories become cool. Part of this is probably developmental, mirroring the point where kids come to terms with the fact life isn't fair at the same time their brains are being rewired. Part of this, however, is probably due to the general cultural consensus that looking on the dark side is seen as worldly and mature. Suffering is seen as lending authenticity, both in real life and in fiction.

But as Roger Ebert once noted, while the truth is often unpleasant, making something unpleasant does not automatically make it more true. My problem with a lot of 'dark' fantasy is that it isn't using suffering to make a point. Instead it throws pointless pain and violence and horror at us with the misguided notion that the reader is bound to feel something real.

The first risk of this strategy is simply audience fatigue. The real world is full of scary and depressing things, and we don't need fiction to tell us that. When a fictional world becomes a stream of pointless, hopeless awfulness, we give up. At worst, it becomes 'torture porn' when violence and pain is lovingly described (especially when that description is disproportionate to the rest of the story). This is all kinds of creepy, particularly in the context of sexual violence.

The secondary problem is that it's emotionally shallow. True tragedy draws us in by offering us viable hope, and then crushing that hope at the last moment. Other genres, such as dystopian fantasy and sci-fi, require hope, however slim, to keep the characters and the readers going. But a relentlessly grim world assumes that an adolescent desire to be 'edgy' is enough to keep reader interest when it isn't.

Published on November 18, 2013 03:45

November 15, 2013

The 'Other' Women, Part II

Once upon a time, when I was a wee undergraduate, I had a flatmate who identified as a feminist, and attributed this to having grown up with a certain breed of YA which featured a certain type of female protagonist. More specifically, the female character who draws her powers of awesome Specialness from rejecting stereotypically feminine things and embracing 'boy stuff'.

Once upon a time, when I was a wee undergraduate, I had a flatmate who identified as a feminist, and attributed this to having grown up with a certain breed of YA which featured a certain type of female protagonist. More specifically, the female character who draws her powers of awesome Specialness from rejecting stereotypically feminine things and embracing 'boy stuff'. Enter Yours Truly. It should have been a warning that I'd already butted heads with the campus 'feminist' publication, who had seen fit to print a rebuttal to a piece I wrote about non-Anglo-Western gender roles and folklore*. In response to me sharing some choice tidbits from my history classes, Flatmate decided to share her opinions on how other cultures do gender, and they were not flattering. I will spare you the details, but suffice to say she took issue with the fact that men in other cultures cook or are nurturing with children or do other things which Anglo-western culture deems 'feminine'. Going on the 'masculine means good' standard, this meant that various peoples around the world had, by her estimation, failed at gender. The screaming match which followed was the stuff of legend.

The long-winded moral of this story is as follows:

We need more representations of societies (real or fictional) which don't play by Anglo-western gender norms;We need more nuanced representations of gender and gender roles;Showing that girls need to be 'masculine' to be awesome isn't feminism, it's misogyny in disguise;Coding tasks/roles as feminine is questionable, and coding 'feminine' as 'demeaning' is gawdawful and insulting to everyone;The degree of violence which a character uses to solve their problems should not be proportional to how cool they are;Fiction has a huge influence on squishy young brains. Bottom line, we need actual diversity in our stories, not just safe lip service to difference. That means challenging the easy narrative-- in this case 'women throws off evil oppressive dresses and beats up monsters like a man'-- and find something with more complexity.

*Had it been a factual, academic disagreement, this could have been interesting. However, it was basically a snit explaining how my personal experience was invalid since it didn't conform to the dominant narrative (by dint of being from outside the dominant culture).

Published on November 15, 2013 01:00

November 13, 2013

The 'Other' Women, Part I

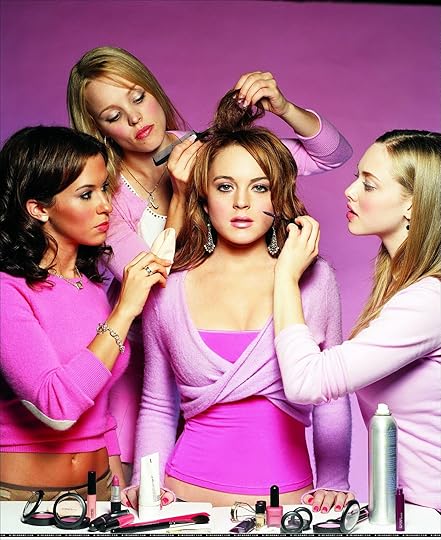

I've been sitting on this post for a while, mostly because of my nagging discomfort with both the original blog post (argument continues along the page) and the responses (just keep scrollin'). For those of you who don't want to click the links, the first is to a post by Sarah Rees Brennan, a YA author with a reputation for being tone-deaf on social issues, responding to general criticism of 'not like other girls' Mary Sue characters by pointing Gary Stu and his clones make up much of YA fantasy's male population, and no one seems too bothered (and that this pattern is present in a lot of fiction, period). The response, by several people, including the Feminazgul of Requires Only That You Hate, point out that in spite of Brennan's protestations that she wants to see greater diversity of YA lady leads, she's still stuck in a very narrow upper-middle-class Anglo-western perspective, and worse, is still engaged in subtly insulting other women based on their interests and gender expression.

I've been sitting on this post for a while, mostly because of my nagging discomfort with both the original blog post (argument continues along the page) and the responses (just keep scrollin'). For those of you who don't want to click the links, the first is to a post by Sarah Rees Brennan, a YA author with a reputation for being tone-deaf on social issues, responding to general criticism of 'not like other girls' Mary Sue characters by pointing Gary Stu and his clones make up much of YA fantasy's male population, and no one seems too bothered (and that this pattern is present in a lot of fiction, period). The response, by several people, including the Feminazgul of Requires Only That You Hate, point out that in spite of Brennan's protestations that she wants to see greater diversity of YA lady leads, she's still stuck in a very narrow upper-middle-class Anglo-western perspective, and worse, is still engaged in subtly insulting other women based on their interests and gender expression.The reason I am uncomfortable here is because I think both sides raise legitimate points, and, simultaneously, both are missing the memo. In Brennan's defence, we don't see a lot of ladies in genre fiction, and we are really short on ladies who use their brains instead of smashing things with weapons in an attempt to be 'strong women' or 'just like the guys'. Honestly, I'd like to see more main characters who solve problems with cleverness instead of violence, and for that matter stories where the obvious solution doesn't involve Stuff Blowing Up. So I totally empathise with the desire to put more quiet, academic lady leads into the mix.

At the same time, the other bloggers rightfully pointed out that giving us a heroine who doesn't rigidly adhere to Western gender norms often means dissing women who do, particularly by making them the main character's petty antagonists. It's also annoyingly common for the female character to be Special because she rejects feminine norms (refusing to wear dresses, etc), which brings us to the implication that femininity itself is bad and the only way for a woman to achieve awesomeness is to try to be a dude. It also implies that people who enjoy 'feminine' gender performance are vapid sheeple.

Furthermore, the Special male characters get their Chosen on by conforming to social expectations of masculinity. Besides Gary Stu Classic, there is also the bookish or non-confrontational guy who becomes awesome by learning to solve his problems with violence. When we see more 'feminine' male characters in YA, the main conflict is about their orientation/gender expression, rather than their gender non-conformity setting them on the path to greatness. While Brennan is correct that the Gary Stus go about their business with much less scrutiny than similar female wish-fulfillment characters, she misses the gender imbalance that underpins the problem.

Finally, I wonder if the bookish female protagonist-- who is typically coded as middle-class, heterosexual, and culturally Anglo-Western-- is a way for authors to create a character who is 'other' enough to appeal to the general sense of persecution which hangs over most teenagers, but not so 'other' as to disturb the status quo.

Now what should happen to this delicate dance of gender policing if someone should introduce gender norms from another culture? Stay tuned.

Published on November 13, 2013 03:45

November 11, 2013

Rememberance Day

For those past, for those currently serving their country, and for those who have returned.(Click through for charity suggestions) One ever hangs where shelled roads part.In this war He too lost a limb,But His disciples hide apart;And now the Soldiers bear with Him.Near Golgotha strolls many a priest,And in their faces there is prideThat they were flesh-marked by the BeastBy whom the gentle Christ's denied.The scribes on all the people shoveAnd bawl allegiance to the state,But they who love the greater loveLay down their life; they do not hate. --Wilfred Owen Monday's post will appear tomorrow morning.

One ever hangs where shelled roads part.In this war He too lost a limb,But His disciples hide apart;And now the Soldiers bear with Him.Near Golgotha strolls many a priest,And in their faces there is prideThat they were flesh-marked by the BeastBy whom the gentle Christ's denied.The scribes on all the people shoveAnd bawl allegiance to the state,But they who love the greater loveLay down their life; they do not hate. --Wilfred Owen Monday's post will appear tomorrow morning.

One ever hangs where shelled roads part.In this war He too lost a limb,But His disciples hide apart;And now the Soldiers bear with Him.Near Golgotha strolls many a priest,And in their faces there is prideThat they were flesh-marked by the BeastBy whom the gentle Christ's denied.The scribes on all the people shoveAnd bawl allegiance to the state,But they who love the greater loveLay down their life; they do not hate. --Wilfred Owen Monday's post will appear tomorrow morning.

One ever hangs where shelled roads part.In this war He too lost a limb,But His disciples hide apart;And now the Soldiers bear with Him.Near Golgotha strolls many a priest,And in their faces there is prideThat they were flesh-marked by the BeastBy whom the gentle Christ's denied.The scribes on all the people shoveAnd bawl allegiance to the state,But they who love the greater loveLay down their life; they do not hate. --Wilfred Owen Monday's post will appear tomorrow morning.

Published on November 11, 2013 03:11

November 8, 2013

The Russo Test

In an attempt to quantify the presence of LGBT* characters in film, GLADD recently created a criteria, nicknamed the 'Russo Test'. While it was designed for films, it can easily be transferred to comics, books, TV series, or any other media. The criteria are as follows:The film contains a character that is identifiably lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender.That character must not be solely or predominantly defined by their sexual orientation or gender identity. I.E. they are made up of the same sort of unique character traits commonly used to differentiate straight characters from one another.The LGBT character must be tied into the plot in such a way that their removal would have a significant effect. Meaning they are not there to simply provide colorful commentary, paint urban authenticity, or (perhaps most commonly) set up a punchline. The character should matter.The criteria was applied to hundred and one top-grossing films of 2012, and the results were rather disappointing. Only thirty-one LGBT characters managed to squeeze in, including fleeting cameos and bit-part characters. It is particularly annoying to note that between all of the 'genre' films-- the catch-all for sci-fic and fantasy action flicks-- only three featured an LGBT characters. Given that these types of movies (or books) tend to have large casts, and that about 8-10% of the general population is LGBT, that's some serious underrepresentation.

In an attempt to quantify the presence of LGBT* characters in film, GLADD recently created a criteria, nicknamed the 'Russo Test'. While it was designed for films, it can easily be transferred to comics, books, TV series, or any other media. The criteria are as follows:The film contains a character that is identifiably lesbian, gay, bisexual, and/or transgender.That character must not be solely or predominantly defined by their sexual orientation or gender identity. I.E. they are made up of the same sort of unique character traits commonly used to differentiate straight characters from one another.The LGBT character must be tied into the plot in such a way that their removal would have a significant effect. Meaning they are not there to simply provide colorful commentary, paint urban authenticity, or (perhaps most commonly) set up a punchline. The character should matter.The criteria was applied to hundred and one top-grossing films of 2012, and the results were rather disappointing. Only thirty-one LGBT characters managed to squeeze in, including fleeting cameos and bit-part characters. It is particularly annoying to note that between all of the 'genre' films-- the catch-all for sci-fic and fantasy action flicks-- only three featured an LGBT characters. Given that these types of movies (or books) tend to have large casts, and that about 8-10% of the general population is LGBT, that's some serious underrepresentation.I find this worth addressing for several reasons. First of all, speculative fiction in general is a big offender here, particularly urban fantasy. Bluntly, we need more queer people, more disabled people, and more people of colour showing up in Urban Fantasy City.

Second, I care because of the harsh contrast created by the genre's fixation on the sex lives of the hetero characters. Generally, I couldn't care less about the orientations of the characters in works where no one really has time for romance, because it would just gum up the plot. And if the stories had a lack of 'out' LGBT characters due to their focus on madcap adventures, that would be awesome. However, love interests/sex interests seem to be mandatory, and if you're going to bring sexuality and sexual orientation into the mix, you'd better have some who aren't straight**.

*Intersex, asexual and other queer folks not included, unfortunately. **I exclude characters who act on same-sex attraction for the titillation of other characters. If you don't get why this is incredibly demeaning, your name may be Laurell K. Hamilton.

Published on November 08, 2013 01:49