Walter Coffey's Blog, page 176

May 5, 2014

The Civil War This Week: May 5-11, 1864

Thursday, May 5

The Battle of the Wilderness began in Virginia as General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia attacked the Federal Army of the Potomac under General Ulysses S. Grant in a region of heavy woods and underbrush. Grant had tried to move around Lee’s right, but Lee attacked first in the Wilderness area to offset Federal superiority in manpower and artillery.

Chaotic fighting raged as reinforcements arrived for both sides. Units got lost in the brush and fires burned wounded troops to death. The ragged lines surged back and forth, and by nightfall there was no clear winner. Both armies entrenched and prepared to continue the fight tomorrow.

Meanwhile, Federal General Benjamin F. Butler’s 30,000-man Army of the James landed at City Point and Bermuda Hundred, within striking distance of both Petersburg and the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Butler faced less than 2,000 Confederate defenders. Confederate President Jefferson Davis informed Robert E. Lee of Butler’s landing.

Federal cavalry raided toward Petersburg and the Weldon Railroad until 11 May. Other Federal cavalry under Brigadier General William Averell raided the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad; this was one of three Federal forces operating in and around Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.

In North Carolina, a Confederate attack at New Berne was repulsed as the ironclad Albemarle fought Federal ships on the Roanoke River. The repulse at New Berne enabled the Federals to retain control of Albemarle Sound.

Federal expeditions began from Craighead and Lawrence counties, Missouri, and in Meade and Breckinridge counties, Kentucky. Skirmishing occurred as part of the Red River campaign. Skirmishing also occurred in Georgia.

Friday, May 6

The Battle of the Wilderness continued in Virginia as the lines of Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee surged back and forth. Federals nearly captured Lee’s headquarters until Confederates under General James Longstreet hurried to plug the hole. Longstreet was accidentally shot by his own men; doctors pronounced his wounds “not necessarily mortal,” and Lee himself temporarily assumed command of Longstreet’s men.

Grant ordered a general attack, but Lee struck first. The Federal left held firm, but the Federal right nearly collapsed and the Confederates almost cut the Federal supply line before the Federals regrouped and held firm. Brushfires in the Wilderness burned wounded troops to death as the fight ended at nightfall in stalemate. The Federals suffered 17,666 killed, wounded, or missing, while the Confederates lost about 7,500.

Lee hoped that the Federals would withdraw just as they had done following previous battles. However, Grant told a Washington correspondent, “If you see the President, tell him, from me, that whatever happens, there will be no turning back.”

On the James River, Benjamin Butler assembled his Federal army within seven miles of Petersburg and 15 miles of Richmond. President Davis called on General P.G.T. Beauregard, commander of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, to assemble all available forces to defend the region: “I hope you will be able at Petersburg to direct operations both before and behind you, so as to meet necessities.” Davis also called all available troops from South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida to come to Virginia.

Confederates captured U.S.S. Granite City in Calcasieu Pass, Louisiana. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Florida, Louisiana, and California.

Saturday, May 7

This morning, Ulysses S. Grant ordered Major General George G. Meade, commander of the Federal Army of the Potomac, to “make all preparations during the day for a night march to take position at Spotsylvania Court House…” The Federals were to move southeast against Robert E. Lee’s right once more. But more significantly, the movement was an advance and not a retreat. Federal troops cheered the decision. Spotsylvania was an important intersection where Lee’s main supply routes met. If the Federals captured the town, they could position themselves between Lee and Richmond.

In Georgia, skirmishing occurred as Major General William T. Sherman’s 100,000-man Army of the West began moving around the left (or western) flank of the 45,000-man Confederate Army of Tennessee under General Joseph E. Johnston. Sherman planned a series of movements around Johnston’s left to avoid a frontal assault or fighting in narrow mountain passes that would offset the Federals’ numerical superiority.

On the James River, Benjamin Butler’s 8,000 Federal cavalry captured the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad, but when they were attacked by a smaller Confederate force, Butler ordered the Federals to withdraw.

At a Marine band concert in Washington, President Abraham Lincoln declined to make a speech but proposed three cheers for Grant “and all the armies under his command.” C.S.S. Raleigh went aground and had to be destroyed after engaging four Federal vessels off the mouth of the Cape Fear River, North Carolina. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Alabama, and Louisiana.

Sunday, May 8

In Virginia, Federals arrived at Spotsylvania Court House to find Confederates already blocking their path. Reinforcements poured into both lines, and a 10-day battle ensued that featured one of the most complex trench systems in history.

In Georgia, Federal troops under General James McPherson formed the right wing of William T. Sherman’s army and advanced into Snake Creek Gap to outflank Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederates. Skirmishing occurred in West Virginia, Alabama, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

Monday, May 9

The Battle of Spotsylvania continued in Virginia, as heavy fighting took place between advancing Federals and defending Confederates. President Davis wrote Robert E. Lee, “Your dispatches have cheered us in the anxiety of a critical position…”

Major General Philip Sheridan’s Federal cavalry began a 16-day raid toward Richmond. Sheridan had been dispatched by General Ulysses S. Grant when Sheridan boasted that he could defeat Confederate General Jeb Stuart’s cavalry if allowed.

Benjamin Butler stalled on the James River, thinking that Confederate resistance was stronger than it was. Soldiers called the campaign a “stationary advance.” As Butler hesitated, the Confederate defenses were strengthened.

In Georgia, William T. Sherman’s Federals under Generals George Thomas and John Schofield pressed Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederates near Dalton. Meanwhile, Federals under James McPherson advanced through Snake Creek Gap, but McPherson withdrew after determining that Confederate defenses were too strong. Sherman was disappointed by McPherson’s withdrawal.

On the Red River in Louisiana, a Federal engineer instructed roughly 3,000 troops in building a dam using trees, rocks, barges, and dirt. Bands of Confederate guerrillas sporadically attacked Federal ships on the river, which were in danger of being stuck in mud due to unusually low water levels.

Major General Stephen D. Lee assumed command of the Confederate Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana, as General Leonidas Polk and many of his troops had gone to join Joseph E. Johnston in Georgia. In Washington, President Lincoln told a serenading group, “Our commanders are following up their victories resolutely and successfully… I will volunteer to say that I am very glad at what has happened; but there is a great deal still to be done.”

In St. John’s River, Florida, Confederates destroyed the U.S. transport Harriet A. Weed. Federal expeditions began from the Fort Crittenden in the Utah Territory to Fort Mohave in the Arizona Territory; from Indian Ranch to Cedar Bluffs in the Colorado Territory, and against Indians in Arizona. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Kentucky, and Arkansas.

Tuesday, May 10

The Battle of Spotsylvania continued in Virginia, as Federals launched a general attack. Defending against repeated assaults, the Confederate lines formed the shape of a mule’s shoe. Temporary Federal breakthroughs at various points were repulsed, particularly at the “Mule Shoe” salient of the line.

Philip Sheridan’s Federal cavalry skirmished with Jeb Stuart’s Confederates along the North Anna River and near Beaver Dam Station in Virginia.

In Georgia, Joseph E. Johnston learned of James McPherson’s efforts to turn his left at Resaca and Snake Creek Gap. Skirmishing continued as Leonidas Polk’s corps from Mississippi was on the way to reinforce Johnston. William T. Sherman decided that since McPherson had failed, he would swing his entire army by the right flank through Snake Creek Gap.

Federal Rear Admiral Dahlgren’s ship commanders voted against a direct attack on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. A Federal expedition began from Pilot Knob, Missouri. Skirmishing occurred in West Virginia, Virginia, Tennessee, and Arkansas.

Wednesday, May 11

The Battle of Yellow Tavern occurred between Philip Sheridan’s Federal cavalry and Jeb Stuart’s Confederates about six miles north of Richmond. The Confederates held their ground despite being outnumbered three-to-one; Stuart was mortally wounded and his command was given to General Fitzhugh Lee. Sheridan drove the Confederates back, but the fight gave them time to strengthen defenses around Richmond.

The Battle of Spotsylvania continued in Virginia, with a brief lull in the heavy fighting. President Davis wrote Robert E. Lee that he was trying to send more troops, but “we have been sorely pressed by enemy on south side. Are now threatened by the cavalry…”

In Georgia, William T. Sherman ordered a general Federal movement from Snake Creek Gap toward Resaca to begin tomorrow.

In the Red River campaign, three Federal ironclads escaped from Alexandria, Louisiana after dams raised the water level. The Louisiana constitutional convention adopted a new ordinance of emancipation without compensation. It was ratified by popular vote on 22 July.

President Lincoln and General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant created a new Military Division of West Mississippi, commanded by Major General E.R.S. Canby, who superseded Nathaniel Banks on the Red River and Frederick Steele in Arkansas. Banks’ command was ultimately redistributed to Canby and William T. Sherman in Georgia.

A Federal expedition began from Point Lookout, Maryland to the Rappahannock River in Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia.

—–

Primary Source: Long, E.B. and Long, Barbara, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971), p 492-499

April 28, 2014

The Civil War This Week: Apr 28-May 4, 1864

Thursday, April 28

Confederate President Jefferson Davis wrote to General Edmund Kirby Smith in the Trans-Mississippi Department, “As far as the constitution permits, full authority has been given to you to administer to the wants of your Dept., civil as well as military.”

Federals began a minor bombardment of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor; 510 rounds were fired at the fort over the next seven days. A Federal expedition began from Vienna, Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in Arkansas, Missouri, and California.

Friday, April 29

The U.S. Congress passed a joint resolution raising all tariffs 50 percent for 60 days; the rate was later extended to 1 July. Federal expeditions began from Ringgold, Georgia and Newport Barracks, North Carolina. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

Saturday, April 30

President Davis wrote to General Leonidas Polk, commanding the Army of Mississippi, “Captured slaves should be returned to their masters on proof and payment of charges.”

President Davis’ five-year old son Joseph died after falling off the second floor rear balcony of the Confederate Executive Mansion. The Davises were inconsolable. Davis could not concentrate on dispatches from Robert E. Lee, and First Lady Varina Davis screamed for hours. Both Presidents Lincoln and Davis lost young sons during the war.

President Abraham Lincoln wrote to General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant, expressing his “entire satisfaction with what you have done up to this time, so far as I understand it.”

Three Confederate blockade-runners escaped from Galveston, Texas under cover of night. A Federal expedition began from Memphis, Tennessee to Ripley, Mississippi. Skirmishing occurred in Arkansas as Federals under General Frederick Steele continued their retreat from Camden.

Sunday, May 1

Skirmishing in Georgia intensified due to the increase in Federal scouting as part of Major General William T. Sherman’s plan to invade the state. General-in-Chief Grant had not given Sherman a specific objective, but Sherman focused on Atlanta, the “Gate City of the South,” about 100 miles southeast of Chattanooga. Atlanta was the Confederacy’s second-most important city behind Richmond. It was not only a vital industrial center, but also a doorway to the Atlantic Coast.

Brigadier General John P. Hatch assumed command of the Federal Department of the South, replacing Major General Quincy A. Gillmore. Skirmishing occurred in Louisiana as part of the Federals’ failed Red River campaign. Skirmishing also occurred in Arkansas and California.

Monday, May 2

The first session of the Second Confederate Congress assembled in Richmond. In his annual message, President Davis condemned the “barbarism” of the Federals in their “Plunder and devastation of the property of noncombatants, destruction of private dwellings, and even of edifices devoted to the worship of God; expeditions organized for the sole purpose of sacking cities, consigning them to the flames, killing the unarmed inhabitants, and inflicting horrible outrages on women and children.” He did not anticipate receiving foreign recognition, but he expressed optimism regarding military and domestic affairs.

A Federal expedition began from Hickman County, Tennessee and along the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad in southwestern Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in Louisiana as part of the Red River campaign. Skirmishing also occurred in Georgia, Tennessee, Missouri, and California.

Tuesday, May 3

General-in-Chief Grant issued orders through Major General George G. Meade that the Federal Army of the Potomac was to cross the Rapidan River tomorrow morning, move around the right flank of General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, and force Lee to block the path to Richmond.

President Lincoln and his cabinet discussed alleged atrocities by Confederates during the attack on Fort Pillow, Tennessee last month. Four cabinet members called for the execution of an equal number of Confederate prisoners. Lincoln, unsure of the facts, condemned the alleged atrocity but decided against retaliatory executions. Lincoln was widely criticized by outraged northerners for not retaliating.

The first column of Frederick Steele’s Federal army returned to Little Rock, Arkansas after retreating from Camden. Skirmishing occurred in Georgia, Louisiana, Arkansas, and the Colorado Territory.

Wednesday, May 4

Ulysses S. Grant’s campaign to destroy Robert E. Lee’s army and capture Richmond began as the Federal Army of the Potomac started crossing the Rapidan River after midnight. Grant’s forces outnumbered Lee’s by nearly two-to-one, but Lee correctly guessed Grant’s plan and prepared to stop him. As the Federals crossed the Rapidan, they stumbled through a dense forest called the Wilderness. Lee planned to attack there, where Grant’s numerical superiority could be offset by the woods.

Federals gathered in the Wilderness and stopped to await the arrival of their supply trains. Many camped on the site of the Battle of Chancellorsville fought almost exactly one year ago. When a newspaper correspondent asked Grant how long it would take him to reach Richmond, Grant replied, “I will agree to be there in about four days. That is, if General Lee becomes party to the agreement; but if he objects, the trip will undoubtedly be prolonged.” Lee’s forces converged on the Federals in the Wilderness.

As part of Grant’s coordinated Federal offensive, Major General Benjamin F. Butler’s 33,000-man Army of the James assembled in transports at Hampton Roads, Virginia. They were to advance up the James River to attack Petersburg or even Richmond itself. Less than 2,000 Confederates guarded their path.

After capturing Plymouth, North Carolina last month, Confederates continued coastal attacks, particularly at Albemarle Sound. Federal forces abandoned an outpost at Croatan, and the Confederate ironclad C.S.S. Albemarle threatened other Federal positions.

Major General William T. Sherman prepared his Federal Army of the West to invade Georgia. Grant had ordered Sherman to “get into the interior of the enemy’s country as far as you can, inflicting all the damage you can against their war resources.” Sherman commanded three armies: Major General John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio on the left targeted the Western & Atlantic Railroad at Dalton, Georgia; Major General George Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland in the center targeted Ringgold, Georgia; and Major General James B. McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee on the right advanced from northern Alabama. Opposing Sherman’s 98,000-man army was General Joseph E. Johnston’s 45,000-man Army of Tennessee, camped around Dalton. Skirmishing ensued as Sherman’s Federals advanced.

In the Red River campaign, Confederates destroyed a Federal steamer and captured two others. The Federal naval flotilla under Rear Admiral David D. Porter was in danger of being stuck in mud due to unusually low river levels.

The U.S. House of Representatives voted (73 to 59) to pass the controversial Wade-Davis Reconstruction bill, sponsored by Radical Republicans Benjamin Wade of Ohio and Henry W. Davis of Maryland. A Federal expedition began from Vicksburg to Yazoo City, Mississippi. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Louisiana, and the New Mexico Territory.

—–

Primary source: E.B. Long and Barbara Long, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971)

April 21, 2014

The Civil War This Week: Apr 21-27, 1864

Thursday, April 21

President Abraham Lincoln conferred with the governors of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa, and he reviewed 72 court-martial cases.

In the Red River campaign, Major General Nathaniel Banks’ Federal Army of the Gulf continued retreating to their base at Alexandria, Louisiana. They faced constant harassment and skirmishing from pursuing Confederates. Other skirmishing occurred in Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

Friday, April 22

The first two-cent U.S. coin was minted, on which the phrase “In God We Trust” was imprinted for the first time. The phrase had been suggested to Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase by Reverend M.R. Watkinson due to the strong religious sentiment during the war.

President Jefferson Davis wrote to Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk, commander of the Confederate Army of Mississippi, “If the negro soldiers (captured) are escaped slaves, they should be held safely for recovery by their owners. If otherwise, inform me.” Davis added, “Captured slaves should be returned to their masters on proof and payment of charges.”

Confederates continued harassing retreating Federal troops on the Red River. A Federal expedition began from Jacksonport to Augusta, Arkansas. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

Saturday, April 23

Confederates continued harassing retreating Federal troops on the Red River, with a hard fight occurring at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana. Other skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Georgia, and Missouri.

Sunday, April 24

Major General Frederick Steele’s Federal forces in Arkansas faced strong resistance from Confederates in their effort to advance out of Camden and link with Nathaniel Banks’ Federals on the Red River. A Federal expedition began from Ringgold to La Fayette, Georgia. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Alabama, and Louisiana.

Monday, April 25

Confederate Major General Robert Ransom was assigned to command the Department of Richmond, Virginia.

Confederate harassment continued against Steele’s Federals in Camden, Arkansas and Banks’ Federals on the Red River. Banks’ Federals began arriving in Alexandria, Louisiana after their retreat. A Federal expedition began from Bull’s Gap to Watauga River, Tennessee. Skirmishing occurred in Mississippi.

Tuesday, April 26

General Banks’ Federals finally returned to Alexandria, where skirmishing took place for nearly a month. Meanwhile, the Federal vessels on the Red River above Alexandria suffered extensive damage from Confederate guerrillas as they struggled through low water to return to their base. Also, General Steele’s Federals began retreating from Camden, Arkansas after failing to join Banks on the Red River.

Federal troops evacuated Washington, North Carolina after the Confederate capture of Plymouth last week. A Federal expedition began from Jacksonville to Lake Monroe, Florida. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Louisiana, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Wednesday, April 27

President Davis dispatched Jacob Thompson to Canada as a special commissioner on an unofficial mission to discuss a possible peace with Federal officials. The Maryland constitutional convention assembled at Annapolis.

A Federal expedition began from Williamsburg, Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Kentucky, and Missouri.

—–

Primary source: E.B. Long and Barbara Long, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971), p. 487-489

April 14, 2014

The Civil War This Week: Apr 14-20, 1864

Thursday, April 14

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln reviewed 67 court-martial cases and issued several pardons. A Federal expedition began from Camp Sanborn in the Colorado Territory. General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederates skirmished at Paducah, Kentucky, and other skirmishing occurred in eastern Kentucky, Georgia, and Arkansas.

Friday, April 15

The Richmond Examiner assessed what could be expected in the upcoming spring campaign: “So far, we feel sure of the issue. All else is mystery and uncertainty. Where the first blow will fall, when the two armies of Northern Virginia will meet each other face to face; how Grant will try to hold his own against the master spirit of Lee, we cannot even surmise.”

At a large pro-Union meeting in mostly pro-Union Knoxville, Tennessee, Governor Andrew Johnson voiced strong support for slave emancipation. Federal ironclad U.S.S. Eastport was severely damaged by a mine on the Red River; she was destroyed on 26 April to avoid capture. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Tennessee, Louisiana, Arkansas, the Indian Territory, and the New Mexico Territory.

Saturday, April 16

A Federal report on prisoners of war stated that Federal forces had captured 146,634 Confederates. The Federal transport ship General Hunter was destroyed by a torpedo on the St. John’s River in Florida.

In the Red River campaign, skirmishing occurred at Grand Ecore, Louisiana and Camden, Arkansas. Other skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Sunday, April 17

U.S. General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant ordered an end to prisoner exchange. This harmed the Confederacy more, but Grant was harshly criticized by both sides.

Confederate forces under Brigadier General Robert F. Hoke attacked Plymouth, North Carolina on the Atlantic coast.

Confederate women defied local troops in a demonstration demanding bread at Savannah, Georgia. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, North Carolina, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

Monday, April 18

The Confederate attack on Plymouth, North Carolina continued.

Confederates under John S. Marmaduke attacked Federals and a foraging train at Poison Springs, Arkansas. The Federals withdrew after harsh fighting and abandoned 198 wagons. This was another Federal failure in the hapless Red River campaign.

General P.G.T. Beauregard was given command of the Confederate Department of North Carolina and Southern Virginia. Beauregard’s objective was to guard Richmond, southern Virginia, and northern North Carolina, a region threatened by Benjamin Butler’s Federal Army of the James.

Addressing the Baltimore Sanitary Fair, President Lincoln said, “We all declare for liberty; but in using the same word we do not all mean the same thing.”

A Federal expedition began from Burkesville, Kentucky. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Alabama, and Missouri.

Tuesday, April 19

The Confederate assault on Plymouth, North Carolina began in earnest when C.S.S. Albemarle rammed and sunk U.S.S. Smithfield, then drove off other nearby Federal ships. Meanwhile, Confederate troops surrounded Plymouth.

A Federal expedition began up the Yazoo River in Mississippi. Confederates demonstrated against Federals at Marion County, Alabama. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, West Virginia, Tennessee, Mississippi, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Wednesday, April 20

Federals surrendered Plymouth, North Carolina. The Confederates under Robert F. Hoke captured about 2,800 men and vast amounts of supplies. This was one of the few major Confederate victories on the Atlantic coast, and it prompted the Federals to abandon nearby Washington, North Carolina.

Major General Samuel Jones was given command of P.G.T. Beauregard’s former command: the Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

President Lincoln ordered the commutation of death sentences by courts-martial to imprisonment at Dry Tortugas off Key West, Florida. Lincoln also conferred with General-in-Chief Grant, who was planning the spring offensives.

Federal expeditions began from Fort Dalles, Oregon and Fort Walla Walla in the Washington Territory to southeastern Oregon. Skirmishing occurred in Natchitoches, Louisiana and Camden, Arkansas as part of the Red River campaign.

—–

Primary Source: E.B. Long and Barbara Long, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971), p. 485-487

April 13, 2014

The Battle of Pleasant Hill: 150th Anniversary

On the weekend of April 5-6, I had the pleasure of attending a reenactment of the Battle of Pleasant Hill in Louisiana. This was a remarkable event that was extremely well organized, and I was grateful to be a part of it. I am also grateful to all with whom I spoke and signed books for.

Unfortunately, the weather did not cooperate on Sunday the 6th, and I wasn’t able to attend that day. However, the festivities that took place on Saturday the 5th were excellent. I truly hope that they’ll have me back when they do the 151st anniversary next year!

Unfortunately, the weather did not cooperate on Sunday the 6th, and I wasn’t able to attend that day. However, the festivities that took place on Saturday the 5th were excellent. I truly hope that they’ll have me back when they do the 151st anniversary next year!

Excerpt from The Civil War Months on the Battle of Mansfield (Pleasant Hill):

In Louisiana in early April 1864, the Federal advance up the Red River toward Shreveport met increased resistance from Confederates and low water. General Richard Taylor’s Confederates established defensive positions at Sabine Crossroads near Mansfield, just east of the Texas-Louisiana border. As the Federals under General Nathaniel Banks concentrated their force, Taylor attacked three miles south of Mansfield.

The Federals were outflanked and forced to retreat in panic and confusion. A wagon train blocking the retreat route added to the panic. Banks finally formed a defensive line at Pleasant Hill, where the Federals repulsed a Confederate attack to avoid a complete rout. Although the fight at Pleasant Hill was technically a Federal victory, this and the fight at Mansfield ended Federal hopes of advancing up the Red River and conquering eastern Texas.

April 8, 2014

The Civil War This Week: Apr 7-13, 1864

Thursday, April 7

In the Red River campaign, Major General Nathaniel Banks’s Federal Army of the Gulf advanced to near Mansfield, Louisiana. General Richard Taylor’s Confederates skirmished with Banks near Pleasant Hill before pulling back.

Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s Confederate corps was ordered to leave eastern Tennessee and return to General Robert E. Lee’s army in Virginia. Longstreet had been detached from Lee since last September, but he was now needed for Lee’s upcoming spring campaign.

Skirmishing occurred in Alabama, Louisiana, Arkansas, and the New Mexico Territory.

Friday, April 8

In the Red River campaign, the Battle of Sabine Crossroads or Mansfield occurred. Richard Taylor’s Confederates had formed a defensive line at Sabine Crossroads, about three miles south of Mansfield. Taylor resolved to stop Nathaniel Banks’s advance on Shreveport here. Banks’s 12,000 men were spread along a dangerously thin 20-mile line. They also had no naval support due to the low water level on the Red River. The Federals were outflanked and forced to retreat in panic and confusion. A wagon train blocking the retreat route added to the panic. Banks finally established a defensive line at Pleasant Hill.

The U.S. Senate voted 38 to 6 in favor of adding an amendment to the Constitution permanently abolishing slavery. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, South Carolina, Alabama, and Louisiana.

Saturday, April 9

In the Red River campaign, Nathaniel Banks’s Federals formed a defensive line near Pleasant Hill after their defeat yesterday. The Confederates skirmished, then launched a main drive this afternoon, but the Federals held them off to avoid a complete rout. This fight at Pleasant Hill was a Federal victory, but Banks was prevented from advancing further west.

Meanwhile in Arkansas, Federal forces under Major General Frederick Steele were blocked from reinforcing Banks’s campaign. Steele’s Federals skirmished at Prairie D’Ane. And when General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi District, moved to reinforce Richard Taylor in Louisiana, Banks decided to withdraw back down the Red River.

Federal General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant began finalizing his plans by issuing campaign orders to be carried out once the roads dried:

Major General William T. Sherman’s Military Division of the Mississippi would invade Georgia and confront General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate Army of Tennessee, which guarded the vital industrial city of Atlanta.

Major General Franz Sigel’s Army of Western Virginia would invade Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and deprive the Confederacy of vital foodstuffs being harvested there.

Major General Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James would advance up the James River in Virginia and threaten Petersburg, south of Richmond.

Major General Nathaniel Banks’s Army of the Gulf would abandon the Red River campaign, instead moving east to capture Mobile, Alabama.

For Major General George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac, Grant instructed Meade, “Wherever Lee goes, there you will go also.”

All the Federal armies were to advance simultaneously to place overwhelming pressure on the undermanned Confederate forces.

The Confederate torpedo boat Squib damaged U.S.S. Minnesota off Newport News, Virginia by detonating a torpedo and escaping. General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederates operated in western Tennessee.

Sunday, April 10

In the Red River campaign, Nathaniel Banks’s Federals withdrew toward Grand Ecore. In Arkansas, Frederick Steele’s Federals began returning to Little Rock amidst skirmishing. Edmund Kirby Smith ordered Richard Taylor’s Confederates to advance from Pleasant Hill to Mansfield.

A Federal expedition began from Dedmon’s Trace, Georgia. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee.

Monday, April 11

In the Red River campaign, Nathaniel Banks returned to Grand Ecore after suffering one of the most humiliating Federal failures of the war. Meanwhile, Admiral David D. Porter’s supporting naval flotilla was in the most danger due to unusually low water levels on the Red River. The boats were under continuous fire by Confederate guerrillas on the riverbanks, and if Porter did not withdraw quickly, his flotilla could be stuck in mud and easily destroyed.

In Arkansas, a pro-Union state government took office at Little Rock, led by Governor Isaac Murphy. In Virginia, a pro-Union delegation approved a constitution for the “Restored State of Virginia,” which included abolishing slavery in the state. The pro-Union government in Virginia, led by F.H. Pierpont, represented only the northern and coastal regions under Federal occupation.

Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederates raided Columbus, Kentucky on the Mississippi. Federal expeditions began from Stevenson, Alabama and Rossville, Georgia. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Alabama, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Tuesday, April 12

General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate cavalry captured Fort Pillow, Tennessee, about 75 miles north of Memphis on the Mississippi River. Forrest had targeted the fort as part of his campaign to destroy Federal communications and supplies; he also sought to avenge Federal atrocities against local civilians. Despite being hopelessly outnumbered, the fort commander refused to surrender, and the garrison was quickly overrun.

Federals later charged that the Confederates slaughtered men as they tried to surrender, particularly black troops. Confederates maintained that the Federals continued firing as they fled, forcing the fight to continue. Of the 557 Federal defenders, Forrest’s men inflicted 331 casualties while suffering only 14 killed and 86 wounded. Of the Federal losses, 204 of the 262 black troops were killed. The high death percentage among blacks sparked northern charges that the Confederates had committed a massacre. Fort Pillow became one of the most controversial incidents of the war.

Major General Simon B. Bucker assumed command of the Confederate Department of East Tennessee. General Robert E. Lee, commanding the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, wrote to President Jefferson Davis, “… I cannot see how we can operate with our present supplies. Any derangement in their arrival, or disaster to the R.R. (railroad) would render it impossible for me to keep the army together…”

Federal expeditions began from Point Lookout, Maryland; Bridgeport, Alabama; and Matagorda Bay, Texas. Skirmishing occurred in Tennessee, Alabama, Louisiana, Arkansas, and the Colorado Territory.

Wednesday, April 13

In the Red River campaign, David D. Porter’s Federal naval flotilla reached Grand Ecore, and Nathaniel Banks’s Federal retreat continued. In Arkansas, Frederick Steele’s Federals were bogged down with no hope of reinforcing Banks.

Federal expeditions began from Portsmouth and Norfolk, Virginia. Skirmishing occurred in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Arkansas.

—–

Primary Source: E.B. Long and Barbara Long, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971) p. 481-85

March 31, 2014

The Civil War This Week: Mar 31-Apr 6, 1864

Thursday, March 31

In the Red River campaign, skirmishing occurred at Natchitoches, Louisiana. Skirmishing also occurred in South Carolina, Florida, Kentucky, and Arkansas. A Federal expedition began from Bridgeport, Alabama.

Friday, April 1

In the Red River campaign, skirmishing occurred at Arkadelphia, Arkansas as General Frederick Steele’s Federals continued moving south to meet General Nathaniel Banks in Louisiana.

The U.S. transport Maple Leaf sank after hitting a torpedo or mine in St. John’s River, Florida. Federal expeditions began from Palatka, Florida and along the Pearl River in Louisiana.

Saturday, April 2

Confederates destroyed Lookout Light, North Carolina. Skirmishing occurred in Florida, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

Sunday, April 3

In the Red River campaign, skirmishing occurred at Grand Ecore, Louisiana. Eight gunboats and three other vessels brought Federal reinforcement to General Banks’s expedition.

General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederates skirmished near Raleigh, Tennessee. Federals began shelling Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor for the next four days. Skirmishing occurred in Georgia, Tennessee, Mississippi, Missouri, Arkansas, and the Indian Territory.

Monday, April 4

Major General Philip Sheridan became the new cavalry commander for the Army of the Potomac. He was one of several western commanders whom Ulysses S. Grant brought East. Sheridan replaced Brigadier General David McM. Gregg. When an officer remarked that Sheridan was too small to head the cavalry, Grant replied, “You will find him big enough for the purpose before we get through with him.” Several other corps commander changes were made in the Federal armies.

In Washington, the House of Representatives approved a joint resolution declaring that the U.S. would not allow France to establish a monarchy in Mexico. This intended to stop Napoleon III from naming Archduke Maximilian of Hapsburg as the Mexican ruler, which violated the U.S. policy of refusing to tolerate European colonization in the Americas as stated in the Monroe Doctrine.

In the Red River campaign, skirmishing occurred in Arkansas and at Campti, Louisiana. The New York Sanitary Commission Fair opened, eventually collecting $1.2 million for soldiers’ needs. President Lincoln wrote, ”I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong… And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgment and feeling.”

Tuesday, April 5

General Banks’s Federal expedition slowed on the Red River due to low water; skirmishing occurred in Natchitoches, Louisiana. Skirmishing also occurred in North Carolina, Kentucky, Missouri, and Arkansas.

Wednesday, April 6

In Louisiana, a pro-Union convention in New Orleans approved a new state constitution that included abolishing slavery in the state.

The Federal Department of the Monongahela was merged into the Department of the Susquehanna. Skirmishing occurred in Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas.

—–

Primary Source: E.B. Long and Barbara Long, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971), p. 479-81

March 28, 2014

George Washington and Non-Intervention

President George Washington set a precedent of non-intervention in European affairs, a trend that lasted into the 20th century.

In 1793, the French Revolution climaxed with the beheading of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The revolutionaries then declared war on Great Britain, Spain, and the Netherlands. Most Americans had supported the Revolution, remembering France’s help in securing American independence from Britain. However, the King’s execution disillusioned many American supporters of the revolution, and France’s declaration of war caused even more dismay in the U.S.

Nevertheless, radical Americans cheered the demise of Louis and Marie. Amidst wild celebrations in the East, Boston’s Royal Exchange Alley was renamed Equality Lane, and radical New Yorkers changed King Street to Liberty Street. Such a display of support threatened to embroil the U.S. in the European conflict, and President Washington sought to avoid such involvement.

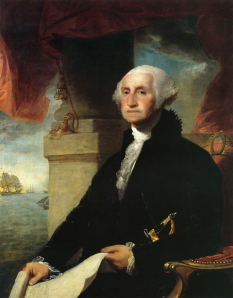

President George Washington

Washington’s effort was threatened in April 1793 with the arrival of the minister of the new French Republic to the U.S., Edmond-Charles-Edouard Genet. Under the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, the U.S. was obligated to treat France’s enemies as its own, just as France had done during the U.S. War for Independence. Thus, Washington and his cabinet agreed to receive “Citizen Genet” as a diplomat, even though such an action could have prompted France’s enemies to declare war on the U.S.

On the other hand, U.S. officials noted that the 1778 treaty had been between the U.S. and the French monarchy, not the new French Republic, and thus could be legally disregarded. But Washington did not want to go that far because it could have been construed as lack of gratitude for France’s contribution to U.S. independence. He and his cabinet continued discussing viable options.

Meanwhile, “Citizen Genet” was warmly welcomed upon landing at Charleston, South Carolina. Instead of immediately traveling to the temporary U.S. capital at Philadelphia to present his diplomatic credentials, Genet instead remained in South Carolina. In a serious breach of diplomatic protocol, Genet effectively went over Washington’s head by commissioning U.S. ships to raid British shipping along the U.S. coast and enlisting Americans to invade Spanish Florida and Louisiana.

Genet’s actions were turning the European conflict into a political crisis in the U.S. Washington finally responded on April 22 by issuing a proclamation that the U.S. would not intervene in the war between the French Republic and its enemies. The word “neutrality” was carefully omitted to avoid offending Britain, whom the U.S. relied on heavily for trade. This allowed the British to continue harassing French shipping bound for U.S. ports.

Washington and his cabinet agreed that this policy best served U.S. interests, as the U.S. could not intervene in Europe and develop its own national economy and interstate relationship under the new Constitution at the same time. Congressman James Madison of Virginia questioned whether Washington had the authority to issue such a proclamation without first obtaining the Senate’s consent.

When Genet finally arrived in Philadelphia after stirring public opinion against France’s enemies, he was informed by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson that Washington’s proclamation prohibited U.S. citizens from openly aiding France. Genet met with Washington and urged the president to withdraw his proclamation. Washington refused, and Genet agreed not to commission any more privateers to raid British shipping off U.S. waters.

However, Genet reneged on his pledge and commissioned another raiding vessel. When warned against launching the vessel, Genet threatened to appeal directly to the people for aid. Washington responded by asking France to recall “Citizen Genet” for his breach of protocol and refusal to respect U.S. policy. By this time, the Jacobins had seized power in France, and they threatened to execute Genet if he returned. Genet begged for mercy, and Washington granted him political asylum; Genet became the first foreigner to receive such a distinction in U.S. history.

Jefferson ultimately resigned from Washington’s cabinet because he felt that Washington was more dependent on officials such as Alexander Hamilton regarding foreign affairs. This rift ultimately led to the formation of the party system in U.S. politics. From a foreign policy perspective, Washington’s proclamation of non-intervention in Europe served as a basis for U.S. policy that future presidents followed until U.S. entry in World War I, 124 years later.

—–

Sources:

Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur M., The Almanac of American History (Greenwich, CT: Brompton Books Corporation, 1993), p. 162, 163

Wallechinsky, David and Wallace, Irving, The People’s Almanac (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1975), p. 144

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163; White, Howard Ray, Bloodstains, An Epic History of the Politics That Caused the Civil War (Amazon Kindle Edition), Y1789-93 Loc 7735-55

White, Howard Ray, Bloodstains, Y1789-93 Loc 7735-55

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163; White, Bloodstains Y1789-93 Loc 7754-63

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163; Schweikart, Larry and Allen, Michael, A Patriot’s History of the United States (New York: Penguin Books, 2004), p. 141

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163

White, Bloodstains, Y1789-93 Loc 7763-72; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmond-Charles_Gen%C3%AAt; Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163; Schweikart and Allen, A Patriot’s History of the United States, p. 142; Wallechinsky and Wallace, The People’s Almanac, p. 144

March 24, 2014

The Civil War This Week: Mar 24-30, 1864

Thursday, March 24

Confederates under General Nathan Bedford Forrest captured Union City in western Tennessee. Federal troops left Camp Lincoln, Oregon to operate against Native Americans in the area. President Abraham Lincoln conferred with new General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant at the White House. Skirmishing occurred in Louisiana and Arkansas.

Friday, March 25

General Forrest’s Confederates alarmed residents in the Ohio River Valley by invading Kentucky and briefly occupying Paducah. Forrest’s attack on Fort Anderson was repulsed.

Brigadier General David McM. Gregg replaced Major General Alfred Pleasonton as commander of Federal cavalry in Virginia. Pleasonton was reassigned to Missouri. Federal expeditions began from Batesville, Arkansas and Beaufort, North Carolina. Skirmishing occurred in South Carolina and Arkansas.

Saturday, March 26

General Forrest’s Confederates withdrew back into western Tennessee. General Grant established permanent headquarters with the Federal Army of the Potomac at Culpeper Court House, Virginia. Major General James B. McPherson assumed command of the Federal Army of the Tennessee.

President Lincoln announced that offers of amnesty did not apply to Confederate prisoners of war, but only to Confederates voluntarily coming forward and swearing allegiance to the Union. Confederate President Jefferson Davis argued with the governors of North and South Carolina over trade and troop policies.

Sunday, March 27

General Forrest’s Confederates skirmished at Columbus, Kentucky on the Ohio River. Skirmishing also occurred in Tennessee, Mississippi, Missouri, Arkansas, and California.

Monday, March 28

In one of the most violent anti-war outbursts in the North, about 100 Copperheads attacked Federal soldiers on furlough in Charleston, Illinois. Fighting finally ended when active Federal troops arrived to restore order. Five were killed and over 20 wounded, and the local newspaper reported that “a dreadful affair took place in our town.”

General Nathaniel Banks’s Federal Army of the Gulf advanced northwestward from Alexandria, Louisiana as part of the Red River campaign. Meanwhile, Confederates under General Richard Taylor moved to stop Banks, and General Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department, began organizing defenses to stop General Frederick Steele’s Federals in Arkansas from linking with Banks.

Federal expeditions began from Caperton’s Ferry, Alabama and Gloucester County, Virginia.

Tuesday, March 29

Major General George G. Meade, commanding the Federal Army of the Potomac, decided not to request a formal court of inquiry to investigate his conduct at Gettysburg last July. Meade had initially demanded the investigation to defend himself against criticisms in the press and among his subordinates. However, President Lincoln persuaded him to withdraw his demand.

Federal expeditions began from Lookout Valley, Georgia and Bellefonte, Arkansas. Skirmishing occurred in Alabama, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

Wednesday, March 30

A Confederate outpost was captured at Cherry Grove, Virginia. Federal expeditions began from Lookout Valley, Tennessee; Woodville, Alabama; and Columbus, Kentucky. Skirmishing occurred in Mississippi, Arkansas, and Missouri.

—–

Primary Source: E.B. Long and Barbara Long, The Civil War Day by Day (New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1971), p.

March 20, 2014

The Kansas-Nebraska Firestorm

The creation of Kansas and Nebraska in the 1850s resulted in many unintended consequences, including pushing America into civil war.

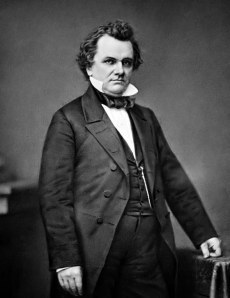

Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas

In January 1854, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois introduced a bill to divide the Nebraska Territory west of Minnesota, Iowa, and Missouri into two territories called Kansas and Nebraska. This land was part of the Louisiana Purchase, and its flat terrain would be ideal for a transcontinental railroad. Douglas, who was a director of the Illinois Central Railroad and a land speculator, envisioned that this would make Chicago a vital trade hub in the Midwest. It could also enable him to win the presidential nomination in 1856.[1]

The Nebraska Territory lay north of the 36-30 parallel, which made it closed to slavery under the terms of the Missouri Compromise (1820). Southerners objected to creating two more territories that excluded slavery. They also objected to building a transcontinental railroad along a northern route, instead favoring a line from New Orleans to San Diego.[2]

To win over southerners, Douglas essentially bribed them into supporting the northern railroad by offering an opportunity to expand slave territory where it had previously been prohibited. Under Douglas’s proposal, the settlers of Kansas and Nebraska would decide for themselves whether or not to allow slaves. This was known as “popular sovereignty,” and if accepted it would cancel the Missouri Compromise that excluded slaves in land north of the 36-30 line.[3]

Douglas’s appeal to southern interests made the territorial issue extremely contentious. If slavery was prohibited from a territory, it would most likely not be settled by slaveholders when it became a state. However, if slavery was allowed in a territory, the chances increased that it would eventually become a slave state. Nebraska was generally considered too far north to make slave labor economically viable, but Kansas held potential for plantation farming. As such, settlers rushed into the region and a violent competition ensued between those in favor and those opposed to slavery.[4]

In response to critics, Douglas argued, “If the people of Kansas want a slaveholding state, let them have it, and if they want a free state they have a right to it, and it is not for the people of Illinois, or Missouri, or New York, or Kentucky, to complain, whatever the decision of the people of Kansas may be.”[5]

Meanwhile, a group of antislavery politicians led by Salmon P. Chase of Ohio and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts published a tract calling the repeal of the Missouri Compromise a slaveholders “plot” and warned that in time, “The blight of slavery will cover the land.” The appeal asked, “Shall a plot against humanity and democracy so monstrous, and so dangerous to the interests of liberty throughout the world, be permitted to succeed?” This helped turn northern opinion against both slavery in general and the proposed Kansas-Nebraska Bill in particular.[6]

The Senate passed the bill, mostly because of Douglas’s influence among the balance between northern and southern senators. Debate in the House of Representatives was more intense because most representatives were northern opponents. However, President Franklin Pierce announced support for the bill and warned that opposition could affect federal patronage jobs. The House finally relented, and Pierce signed “An Act to Organize the Territories of Nebraska and Kansas” into law on May 30, 1854.[7]

The new law effectively split the Democratic Party along north-south lines and virtually destroyed the fledgling Whig Party. Northern Whigs and Democrats soon joined Free-Soilers in forming a new “anti-Nebraska” coalition that became known as the Republican Party. The Republicans were the first purely sectional party, adopting a strict anti-southern agenda by supporting high tariffs on imports, subsidies to favored businesses, and economic nationalization.[8]

Kansas soon erupted into violence between pro and antislavery factions, and the region became known as “Bleeding Kansas.” The antislavery faction, mostly comprised of northern Republicans, supported excluding not only slaves but all blacks from Kansas. This was in keeping with the Republican Party’s 1856 platform declaring that “all unoccupied territory of the United States, and such as they may hereafter acquire, shall be reserved for the white Caucasian race–a thing that cannot be except by exclusion of slavery.”[9]

Stephen Douglas boasted, “I passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act myself. I had the authority and power of a dictator throughout the whole controversy in both (the Senate and House of Representatives). It was the marshaling and directing of men, the guarding from attacks, and with a ceaseless vigilance preventing surprise.” However, Douglas unwittingly divided the Democrats, helped form the Republicans, instigated lawlessness in the West, and unleashed widespread animosity between North and South from which there would be no return.[10]

[1] Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen, A Patriot’s History of the United States: From Columbus’s Great Discovery to the War on Terror (Sentinel Trade, 2007), p. 272; Kenneth C. Davis, Don’t Know Much About History (New York: HarperCollins, 2009), p. 205

[2] Schweikart and Allen, A Patriot’s History of the United States, p. 272; H.W. Crocker III, The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Civil War (Washington, Regnery Publishing, 2008), p. 25

[3] Schweikart and Allen, A Patriot’s History of the United States, p. 272; Davis, Don’t Know Much About History, p. 205

[4] Thomas E. Woods, Jr., The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History (Washington, Regnery Publishing, 2004), p. 49-51; Crocker III, The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Civil War, p. 25-26

[5] Geoffrey C. Ward, Ken Burns, Ric Burns, The Civil War: An Illustrated History (New York: Alfred Knopf, Inc., 1990), p. 20

[6] Howard Ray White, Bloodstains: An Epic History of the Politics That Produced the American Civil War, Volume 2: The Demagogues (Amazon Kindle E-Book), Ch. 1Q54

[7] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kansas%E2Nebraska_Act

[8] Davis, Don’t Know Much About History, p. 205; Woods, Jr., The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History, p. 51-52

[9] Woods, Jr., The Politically Incorrect Guide to American History, p. 52

[10] White, Bloodstains, Ch. 2Q54