George Washington and Non-Intervention

President George Washington set a precedent of non-intervention in European affairs, a trend that lasted into the 20th century.

In 1793, the French Revolution climaxed with the beheading of King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The revolutionaries then declared war on Great Britain, Spain, and the Netherlands. Most Americans had supported the Revolution, remembering France’s help in securing American independence from Britain. However, the King’s execution disillusioned many American supporters of the revolution, and France’s declaration of war caused even more dismay in the U.S.

Nevertheless, radical Americans cheered the demise of Louis and Marie. Amidst wild celebrations in the East, Boston’s Royal Exchange Alley was renamed Equality Lane, and radical New Yorkers changed King Street to Liberty Street. Such a display of support threatened to embroil the U.S. in the European conflict, and President Washington sought to avoid such involvement.

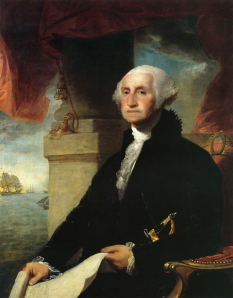

President George Washington

Washington’s effort was threatened in April 1793 with the arrival of the minister of the new French Republic to the U.S., Edmond-Charles-Edouard Genet. Under the 1778 Treaty of Alliance, the U.S. was obligated to treat France’s enemies as its own, just as France had done during the U.S. War for Independence. Thus, Washington and his cabinet agreed to receive “Citizen Genet” as a diplomat, even though such an action could have prompted France’s enemies to declare war on the U.S.

On the other hand, U.S. officials noted that the 1778 treaty had been between the U.S. and the French monarchy, not the new French Republic, and thus could be legally disregarded. But Washington did not want to go that far because it could have been construed as lack of gratitude for France’s contribution to U.S. independence. He and his cabinet continued discussing viable options.

Meanwhile, “Citizen Genet” was warmly welcomed upon landing at Charleston, South Carolina. Instead of immediately traveling to the temporary U.S. capital at Philadelphia to present his diplomatic credentials, Genet instead remained in South Carolina. In a serious breach of diplomatic protocol, Genet effectively went over Washington’s head by commissioning U.S. ships to raid British shipping along the U.S. coast and enlisting Americans to invade Spanish Florida and Louisiana.

Genet’s actions were turning the European conflict into a political crisis in the U.S. Washington finally responded on April 22 by issuing a proclamation that the U.S. would not intervene in the war between the French Republic and its enemies. The word “neutrality” was carefully omitted to avoid offending Britain, whom the U.S. relied on heavily for trade. This allowed the British to continue harassing French shipping bound for U.S. ports.

Washington and his cabinet agreed that this policy best served U.S. interests, as the U.S. could not intervene in Europe and develop its own national economy and interstate relationship under the new Constitution at the same time. Congressman James Madison of Virginia questioned whether Washington had the authority to issue such a proclamation without first obtaining the Senate’s consent.

When Genet finally arrived in Philadelphia after stirring public opinion against France’s enemies, he was informed by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson that Washington’s proclamation prohibited U.S. citizens from openly aiding France. Genet met with Washington and urged the president to withdraw his proclamation. Washington refused, and Genet agreed not to commission any more privateers to raid British shipping off U.S. waters.

However, Genet reneged on his pledge and commissioned another raiding vessel. When warned against launching the vessel, Genet threatened to appeal directly to the people for aid. Washington responded by asking France to recall “Citizen Genet” for his breach of protocol and refusal to respect U.S. policy. By this time, the Jacobins had seized power in France, and they threatened to execute Genet if he returned. Genet begged for mercy, and Washington granted him political asylum; Genet became the first foreigner to receive such a distinction in U.S. history.

Jefferson ultimately resigned from Washington’s cabinet because he felt that Washington was more dependent on officials such as Alexander Hamilton regarding foreign affairs. This rift ultimately led to the formation of the party system in U.S. politics. From a foreign policy perspective, Washington’s proclamation of non-intervention in Europe served as a basis for U.S. policy that future presidents followed until U.S. entry in World War I, 124 years later.

—–

Sources:

Schlesinger, Jr., Arthur M., The Almanac of American History (Greenwich, CT: Brompton Books Corporation, 1993), p. 162, 163

Wallechinsky, David and Wallace, Irving, The People’s Almanac (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1975), p. 144

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163; White, Howard Ray, Bloodstains, An Epic History of the Politics That Caused the Civil War (Amazon Kindle Edition), Y1789-93 Loc 7735-55

White, Howard Ray, Bloodstains, Y1789-93 Loc 7735-55

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163; White, Bloodstains Y1789-93 Loc 7754-63

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163; Schweikart, Larry and Allen, Michael, A Patriot’s History of the United States (New York: Penguin Books, 2004), p. 141

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163

White, Bloodstains, Y1789-93 Loc 7763-72; http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmond-Charles_Gen%C3%AAt; Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163

Schlesinger, The Almanac of American History, p. 163; Schweikart and Allen, A Patriot’s History of the United States, p. 142; Wallechinsky and Wallace, The People’s Almanac, p. 144