CrimethInc.'s Blog, page 4

February 16, 2016

Europe: Between Rape and Racism

As Europe descends further into nationalism and xenophobia, we are seeing feminist, atheist, and progressive discourses appropriated to serve reactionary ends. Following the assaults in Cologne and the media feeding frenzy about “migrant violence,” many people have struggled to find a way to speak about the situation without minimizing the issue of sexual assault or contributing to the demonization of migrants. Yet displacement and sexual assault are not distinct issues—they are interrelated components of a larger context that must be confronted as a whole.

Nationalist graffiti in Slovenia: “Let’s rape leftist women.”

The Story Thus Far

The past decade has seen a series of cascading disasters in the Middle East and Europe. First, there was the bloody occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq, which destabilized the region and ultimately enabled the Islamic State to seize weapons and power. Then a series of civil wars from Mali to Libya and Syria, combined with economic hardship throughout the region, triggered a mass influx of migrants seeking a new life in Europe. In response, European nations closed their borders and attempted to trap migrants in internment camps. Then, in November, Islamist attacks in Paris gave the French government an excuse to declare a state of emergency and intensified the momentum of an already violent backlash against migrants.

In this charged environment, news reports circulated that “gangs of migrants” had carried out a series of sexual assaults in Cologne and elsewhere around Europe on New Year’s Eve. A new series of xenophobic attacks followed, along with demonstrations from Pegida and other nationalist groups. Many demonstrators appropriated slogans from anti-border movements, transforming “Refugees Welcome” into “Rapefugees Not Welcome” and demanding security for “Fortress Europe”—the Nazi expression for Occupied Europe during the Second World War. The overwhelming sentiment from participants was “We need to protect our women.”

On one side, nationalists and fascists sought to exploit the trauma of sexual assault survivors as a tool for promoting hatred. On the other, many people who consider themselves to be feminists and advocates of migrants’ rights struggled to find a way to speak about the situation, afraid of minimizing the issue of sexual assault or contributing to the demonization of migrants.

These are precisely the sort of difficult situations that we will be confronting as the world slides further into crisis, forcing populations into conflict and rupturing the neat and tidy narratives of a seemingly simpler era. If we don’t develop a language with which to articulate the nuances of such situations, reactionaries of all stripes will have a free hand to capitalize on them. In many regions, old-fashioned progressive politics are quickly losing ground to new waves of nationalism, while the state uses security concerns as a pretext to target anyone proposing a radical solution. Rather than ceding the discourse to those who would force us to choose between opposing rape and opposing racism, we have to articulate the ways that displacement and sexual assault are interrelated components of a larger context of oppression that has to be confronted in its entirety.

Cutting through the Tangled Web of Hatred

The invasion of Iraq in 2003 opened the latest chapter in a history of colonial intervention in the Middle East that goes back hundreds of years. Sooner or later, the consequences of this were bound to reach Europe. In 2015 alone, over a million people crossed the Mediterranean Sea, mostly to Greece and Italy, then continued their journey further north. At least 3735 people died or went missing on the sea crossing, including many children. Well over three million more people are currently living in refugee camps in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and North Africa.

Doing their best to conceal their part in creating this disaster, Europe’s political elites dubbed it the “migrant crisis.” This phrase reduces a complex situation to a question of security; in fact, the crisis was not produced by migration, but by destabilization and borders. Tasking security experts with managing the situation, European governments erected new border walls, expanded the authority of the military, dehumanized migrants, and criminalized solidarity efforts.

Germany is one of the primary destinations migrants are trying to reach. Despite its supposed open door policy, Germany has been dividing migrants into deserving and undeserving, welcome and unwelcome—the former being mostly from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, the latter mostly from Northern Africa but also from other war-torn areas such as Pakistan, Somalia, and Eritrea. This means that many migrants are being deported to countries in which their lives are in danger. Switzerland, Denmark, and some southern German states have been confiscating money and valuables from migrants, as well. Right-wing discourse maintains that most migrants entering Europe are young men—but in Slovenia, through which nearly half a million people have passed en route to northern Europe, the official numbers indicate that the majority of those crossing are women and children. Almost 300 refugee hostels have been attacked in Germany, with the pace escalating towards the end of 2015.

A planned asylum center in Germany burns down.

This was the climate in which Cologne’s 2016 New Year’s celebration took place.

According to state reports, approximately a thousand men “of Arab or North African appearance” congregated around Cologne’s Central Station, where groups surrounded, groped, and robbed women. By the end of January, over a thousand people had filed complaints to the police about that night, including three rapes and 433 sexual offenses; charges have been filed against 44 people, ten of whom are in custody. Of those detained by the police, dozens were identified as asylum seekers or other migrants. Similar events were described in Hamburg, Frankfurt, Dortmund, Stuttgart, and as far as away as Helsinki.

The events in Cologne were a windfall for nationalists and xenophobes who had long labored to build a narrative framing migrants as criminals, rapists, and purveyors of militant Islam, despite the fact that many of them are fleeing Islamist violence. Suddenly, all the repressive measures that governments had carried out over the preceding months were retroactively justified.

How seriously should we take this story about a wave of crime, rape, and misogyny? Contrary to right-wing propaganda, official reports show that crime rates among migrants in Germany are no higher than among European citizens. This is significant when we consider that white men are more likely to be treated leniently by the police and court system than men of color.

At the same time, we should never reduce our concern with sexual assault to a matter of statistics; the state does not document all the sexual violence that takes place, nor does it offer any constructive response to it. Likewise, we must not relativize such attacks in a way that takes them for granted. We consider the events in Cologne significant because we oppose all sexual violence, whether the perpetrators are from the upper echelons of political parties or the most oppressed sectors of society. For us, the attacks are specific acts of harm against individual human beings, not a public relations nightmare or an opportunity to promote an ideology. Addressing sexual violence and harassment is always important, even when nationalists attempt to hijack the discussion.

So we must begin from the standpoint of solidarity with everyone targeted by sexual violence, while refusing state and nationalist narratives about how to respond. We need not have the illusion that all migrants are above reproach to see the value in resisting the state repression and racist violence directed at them. On the contrary, since different forms of violence reinforce each other, we recognize that the more effective we are in interrupting the violence of governments and nationalists, the more capable we are likely to be of putting an end to sexual violence and misogyny.

The best way to counter nationalists’ attempt to exploit the Cologne attacks is to take the initiative against rape and misogyny ourselves, while debunking racist narratives about who the majority of rapists and misogynists are. Likewise, one of the ways to put a stop to sexual violence is to oppose the segregation, repression, and xenophobia that fractures the population into mutually hostile factions. This is especially important in the current climate of hatred, when nationalists, Islamists, and media outlets are all bent on representing us to each other in ways that breed distrust and violence. All of them have an interest in fomenting a religious war, dividing Europeans and migrants between the rival camps of Le Pen and al-Baghdadi so we will not find common cause against leaders and wars together. And the more fear, the more conflict, the less trust, the less mutual accountability… the more sexual assaults.

Racist narratives aside, we can’t rule out the possibility that as nationalist violence intensifies, many of those who are targeted will turn to anti-social activity. Already, we have seen how the alienation that led to the Banlieu riots in 2005 is now offering a fertile recruiting field to ISIS. This is yet another example of how reactionary movements and social conflicts spring up wherever we fail to demonstrate the virtues of fighting for total liberation. Unless we act effectively against nationalism and misogyny now, we will find ourselves more and more alone in our efforts to promote a world in which people are not divided along lines of gender, citizenship, ethnicity, and religion.

Defending Us without Our Consent

The demand for more policing complements the militarization of the borders. In a society in which the function of police has always been to preserve the state and male privilege, police will never be on the side of women and others targeted by sexual violence. If sexual violence is really the issue, it would be more effective to promote self-defense and mutual aid between targeted groups. But the nationalists who are suddenly talking about rape and misogyny were not exactly volunteering at domestic violence shelters and rape crisis centers before New Year’s Eve.

In fact, the narrative that women are being victimized by people of a rival ethnic or religious group is the oldest tool in the nationalist toolbox. It is easy to revive this narrative whenever it is convenient because, in a patriarchal society, assaults against women are always taking place, so nationalists can emphasize or conceal them as it serves their purposes. One of the easiest ways to justify violence is to argue that it will prevent or avenge violence against the innocent and defenseless—so in this narrative, women are always portrayed as victims on whose behalf others must take action.

Local Europeans, not migrants, are responsible for most rapes in Europe. Again, this is not a justification for minimizing or relativizing the attacks that took place in Cologne. But the events in Cologne must not be used to justify further attacks and racism in the name of the women who were assaulted.

Let’s look at some earlier instances of this narrative about defending women. In the late 19th and early 20th century, thousands of black men in US were lynched; many of these killings were justified with rhetoric about protecting white women. In 1923, an entire black community was massacred in Florida in response to rumors that a black man had sexually assaulted a white woman. In 1955, white men killed a 14-year-old boy accused of flirting with a white woman. In some cases, lynchings occurred as a result of white women reporting that they had been raped in order to conceal their love affairs; in other cases, lynchings were provoked by the jealousy of husbands. Even explicitly consensual sexual relationships between white women and black men were interpreted as sexual attacks.

Who owns white women’s sexuality? Sexual access to white women has been traditionally seen by white society as a privilege reserved for white men as a symbol of their authority. This legacy continues up to today. In June 2015, 21-year-old Dylann Roof entered Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, announcing “You rape our women, and you’re taking over our country, and you have to go.” He shot and killed nine people.

Despite the general agreement that this was a white supremacist hate crime, Roof was represented to the public as an unfortunate, mentally troubled individual. By contrast, when Muslims engage in violent acts, pundits are quick to identify those acts as terrorism, because such acts are supposedly an inherent part of Muslim identity.

If we compare the lynchings in the American South with the revenge attacks on migrants after the news spread from Cologne, we see two correlations. First, such revenge attacks are randomly directed at members of a group that is portrayed as an undifferentiated whole—in other words, they are racist violence, pure and simple. Second, even in the cases where sexual assaults had in fact taken place, the resulting attacks were not directed by the survivors and involved no real attempt to achieve accountability or take measures against sexism.

Such claims of ownership over women’s bodies and sexuality often coincide with war. During the Balkan wars at the beginning of the 1990s, between ten and sixty thousand (mostly Muslim) women were raped in former Yugoslavia, often repeatedly, in front of family members, or in special camps. Sensationalist media reporting took no steps to protect the identities of women who were raped, while creating a discourse of victimization and erasing the voices of the survivors.

Most (male) politicians interpreted the mass rapes as an attack on national sovereignty. They drowned out the voices of rape survivors by speaking over them, presenting them as victims in order to fight wars in the name of their honor regardless of what the survivors actually wanted. They reduced the survivors to their ethnicities—to playing pieces in an ethnic conflict. The targets of rape were not individual human beings, but Bosnians, Serbs, Croats. This discourse was heard from all sides in the Balkan conflicts: the survivors were “their women.” Not surprisingly, those same men socially rejected survivors who became pregnant as a result of rape; many of their children are still orphans in Bosnia today.

Already in the 1990s, Balkan feminists identified mass rapes as attacks against specific women, not just against an ethnicity, and openly opposed the war itself. Many women organized informal mutual aid for survivors during the war, refusing to permit the care of raped women to be left up to state institutions. These feminists were branded traitors; often, they were assaulted themselves. In 1992, an infamous article in the Croatian newspaper Globus claimed that “Croatian feminists are raping Croatia.”

Here we see how women’s attempts to defend themselves not only against assault but also against unsought “defense” place them outside the narrow zone of protection afforded under patriarchy. Insofar as men or the nation itself are understood as owning the female body, women’s bodies will be considered a resource to be controlled or attacked during wartime—and the desire to own or attack women’s bodies will function as an incentive to go to war. Rather than understanding rape as a weapon of war in a way that creates the demand for other weapons of war to be deployed in response, we can set out to oppose rape in ways that also oppose war itself. This offers some insight into how we might respond to the events in Cologne.

Nationalists aren’t interested in protecting anyone—they just seek to justify the violence they hope to perpetrate. The rhetoric of protection is a thinly veiled threat.

“Let’s Rape Leftist Women!”

Today’s nationalists aspire to preserve Europe as a gated community; their aspirations are couched in the language of property ownership. At the beginning of the migrant crisis, they asserted ownership of the territory of the state: “We must defend our borders against migrants.” Then they asserted ownership of their roles in capitalist production: “The migrants are going to take our jobs.” Later, they took it upon themselves to protect their perverted version of multiculturalism: “We must defend our language, culture, and traditions from migrants.” Finally, they have started to claim ownership of female bodies as well: “We must defend our women from migrant rapists.”

This portrayal of migrants as terrorists who rape European women is nothing new; it has played a central role in right-wing political propaganda for decades. This is the Other—the Foreigner, the Perpetrator—who exists in relation to the European white man, the Protector. The events of New Year’s Eve only confirmed a narrative that had long been circulating on right-wing blogs and message boards, catapulting it onto the front page of the mainstream news.

The narrative that “migrants are rapists” encourages hatred towards all migrants as a single homogenous population. In Europe, particularly in the southeast, this idea that a given ethnic group has an inborn propensity for crime has historically been associated with the Roma population. News reports of assaults by non-white individuals have always specified ethnic, national, or racial descriptors—“A young migrant (or black, or Romani) man raped a woman”—while white men from the dominant ethnic group are not similarly identified.

Today, this sort of racism is often concealed under the argument that Islam is inherently more violent and oppressive than other religions. Even setting aside the obvious counterarguments (the Inquisition, the forcible conversion of the Americas, slavery and genocide in Africa, abortion clinic bombings, Anders Brevik…) it’s clear that this narrative functions to justify the same colonialist interventionism that produced the rise of fundamentalist Islam in the first place. Nationalists are trying to coopt progressive and radical ideas, including atheist critiques of religion as a whole, to craft a story in which the civilized West is forced to do battle with superstitious religious barbarians. Even some ostensibly anarchist groups have published texts that assert this narrative. In fact, if your goal is to undermine the repressive cultural values associated with some forms of Islam, it is more effective to support rebels in Muslim communities than to demonize Muslims as a whole.

The goal of these narratives is to render it impossible to imagine a world without borders. Whoever rejects nationalism is branded naïve—“What would you say if they raped you, or your sister or mother or daughter or wife?”—or else as a supporter of rape. Right-wing rhetoric alleging that “Western women” are to be “sacrificed on the alter of mass migration” in a “rape epidemic” aims to divide radical movements between two subjects we have worked hard to push into the public awareness—rape culture and migrant solidarity. Nationalists are especially eager to force this division, since they have a lot to be defensive about when it comes to misogyny.

If it is possible to make such a distinction in the first place, it is only because those critiques reached the public in a watered-down single-issue liberal form. Likewise, the storyline of man as protector or perpetrator and woman as victim only reinforces the gender binary, pressuring people to adhere to their assigned genders for fear of becoming targets. Claiming to protect women is a way to police everyone’s gender and sexuality.

By the same token, as soon as they speak out about the links between sexual violence and racism, women are considered legitimate targets for the same assaults white men claim to be protecting them from. In Slovenia’s capital Ljubljana, graffiti appeared around the city proclaiming Posilmo Levičarke, “Let’s rape leftist women.” In Slovenia, “levičarke” is a right-wing slur referring explicitly to anarchists, queers, and other antifascists and feminists. The message is clear: everyone who does not line up to support the nation and white manhood is a traitor who should be taught a lesson. Meanwhile, social centers throughout Europe that show solidarity with migrants have been targeted with the same violence aimed at migrant hostels.

Likewise, a month after New Year’s Eve, white Germans groped a reporter who was speaking live on television in Cologne. So long as the idea prevails that women are men’s property, all women can expect to be treated thus, even those who don’t threaten the nationalist agenda. Nationalists aren’t interested in protecting anyone—they just need a way to popularize the violence they wish to perpetrate against migrants and women alike. The rhetoric of protection is a thinly veiled threat.

Nationalist violence continues the process of silencing that began with the sexual assaults, in that it replaces and drowns out the voices of the survivors who should be the ones speaking in the first place. Foremost among those are the migrants who are themselves targeted for sexual assault and harassment. Women traveling from Turkey to Greece and north through the Balkans into the European Union have reported being sexually assaulted and harassed at every stage in the journey. In the transit camps of Croatia, Greece, and Hungary, where they are forced to sleep in the same spaces as men and to use same shower and toilet facilities while being watched, some stopped eating or drinking in order to avoid having to use the toilets. They are often pressured to offer sexual favors to smugglers, camp guards or other security personnel, or other migrants. If nationalists were truly concerned about sexual assault, they would begin with what migrants have been going through.

A migrant sits on a bed at her first registration point.

Sexual violence threatens people everywhere that there are “secure borders” and military controls. In the process of crossing the border between Mexico and the US, almost 80 percent of women from Central America are raped by government officials, cartels, guides, or other migrants. It just came out that minors were raped by United Nations peacekeeping units in Central African Republic, following last year’s revelation that UN troops had sexually abused children in Central African Republic as well as more than 200 women and children in Haiti.

It is no coincidence that so many rapes are perpetrated by representatives of the state. Putting some people in a position of power over others structurally increases the likelihood of rape. Sexual assaults often occur within hierarchical institutions such as prisons, mental heath institutions, churches, schools, offices, and heteronormative families in which the same structures that are supposed to protect people render them vulnerable. If we grant that misogyny and sexual assault exist in Muslim communities—citing, for example, the sexual assaults in Tahrir Square, which Egyptian black bloc anarchists took the lead in resisting—that doesn’t mean that white Europe is free of rape or sexism. They just don’t come to light as often because the perpetrators are protected by their status.

The central question here is not who the rapists are, but how to respond to sexual assault and rape culture in a way that puts an end to them. Imposing more coercive force, exacerbating power imbalances, and creating more conflicts between “peoples” will only intensify the factors that produce rape in the first place. The fight against sexual assault and patriarchy cannot prioritize any specific group, culture, society, or territory. Sexualized violence exists in a feedback loop with other forms of patriarchy, heterosexism, trans oppression, ageism and oppression of youth, colonialism, and genocide. To fight any of these effectively, we have to fight all of them.

A Syrian refugee resists Hungarian police who have taken her husband and are attempting to lock her in an internment camp.

It’s Up to Us

Racism and fascism have gotten a makeover in Europe, casting off the old uniforms in favor of suits and ties. Meanwhile, many previously apolitical people are embracing xenophobia, blaming all the problems caused by capitalism on the most vulnerable and marginalized. As discourses and power alliances are reconfigured in this context, we must be careful not to be drawn into the narratives of our enemies.

No state or nationalist security could offer us the safety that comes from social ties and solidarity that extend across the lines of ethnicity and religion. Just as we seek to unlearn our own sexism and to take responsibility for the ways we do harm to others, we have to understand our world as a single unified space in which neither exclusion nor coercion will put an end to misogyny and sexual violence. The solution to sexual assault has never been to externalize the problem behind bars or across borders. The fight against sexism is not a fight against something external, but against all identities that are constructed within gendered matrices of power, including our own identities. This is a fight we can share with migrants, with survivors, with everyone who has a stake in creating a different world.

The nationalists have no real plan for putting an end to the violence they pretend to oppose. Their strategies of division can only exacerbate it—and perhaps that is their true intention. Dehumanizing or deporting migrants will strengthen the position of the Islamic State, Ansar Dine, Boko Haram, and other groups who want to create a situation in which Muslims have no choice except to join their religious war. This makes it all the more pressing to establish a common struggle with migrants while demonstrating empowering and inclusive solutions to the problem of sexual violence. Rape and racism are manifestations of the same thing. Let’s fight them together.

More pro-rape nationalist graffiti in Slovenia, modified to read “Who is afraid of the leftist woman?” and “Let’s support leftist women.”

February 11, 2016

#46: International Anarchist Reflections

#46: International Anarchist Reflections on the New Year — What do anarchists around the world think is in store for the new year? In Episode 45, we began our 2015 year in review, focusing on the US. In this episode, we share reflections on developments in 2015 and from anarchists in Chile, Finland, Brazil, Korea, Colombia, Czech Republic, and Rojava. There are also discussions about developments in fascism and anti-fascism, with reports from the UK and Australia, and an analysis by Gulf Coast anarchists of the environmental movement’s supposed “victory” over the Keystone XL pipeline in November. On the Chopping Block, we review the latest issue of Perspectives on Anarchist Theory, the journal of the Institute for Anarchist Studies, on the theme of “Justice.” Long term black liberation political prisoner Herman Bell discusses his upcoming parole hearing, and we share plenty of news, including some reflection on a new round of revolts in Tunisia, plus prisoner birthdays, events, listener feedback, and more.

You can download this and all of our previous episodes online. You can also subscribe in iTunes here or just add the feed URL to your podcast player of choice. Rate us on iTunes and let us know what you think, or send us an email to podcast@crimethinc.com. You can also call us 24 hours a day at 202–59-NOWRK, that is, 202–596–6975.

January 25, 2016

To Change Everything in Ten More Languages

Unfortunately, our efforts to update tochangeeverything.com have lagged behind the efforts of comrades around the world to produce versions of To Change Everything in their own languages. We will be updating the site on an ongoing basis, but in the meantime, here are the PDFs of ten more versions of the project, along with the videos for four of them. If you are interested in working on a version for your own language or region, please get in touch!

Català / Catalan

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [4.4MB]

中文 / Chinese

Screen PDF (Spread View) [1.1MB]

Print PDF (A4, B&W, Imposed) [15.5MB]

Dansk / Danish

Screen PDF (Reduced File Size, Single Page View) [869KB]

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [16.8MB]

Print PDF (A6, Color, Imposed) [1.7MB]

Français / French

(continental)

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [19.9MB]

Print PDF (Color, Imposed) [21.1MB]

ελληνικά / Greek

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [1.3MB]

Screen PDF (Spread View) [1.3MB]

Print PDF (A4, B&W, Imposed) [10MB]

Italiano / Italian

Screen PDF (Spread View) [1.6MB]

Print PDF (B&W, Imposed) [5.5MB]

Print PDF (B&W, Imposed, 2-up) [5.8MB]

한국어/ Korean

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [7.6MB]

Română / Romanian

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [20MB]

Русский / Russian

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [16.1MB]

Svenska / Swedish

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [5.4MB]

January 19, 2016

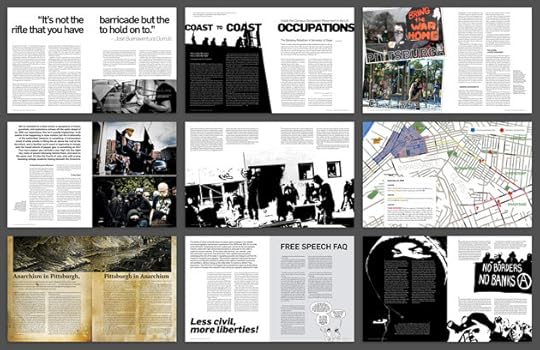

Rolling Thunder #9 Full PDF Now Available

We’ve just mailed out the last print copy of Rolling Thunder #9, and as such, we’re very happy to make the full issue available for download as a beautiful, high-resolution PDF. With issue #9 we were really hitting our stride, and its contents still hold up quite well:

How important is legitimacy—in our own eyes, in the eyes of potential allies, in the eyes of the public? How can anarchists cultivate it? What pitfalls does it hold? Rolling Thunder #9 explores these questions while reporting on the past six months of upheavals around the US. Following up on our coverage of the 2008 convention protests, this issue assesses anarchist action at the 2009 G20 summit, mapping conflict throughout the city and analyzing the strategies of the police and protesters. The accompanying Pittsburgh scene report examines the decade of local organizing that prepared the ground for this and other confrontations. Elsewhere herein, we scrutinize protest and resistance on campus—from the recent occupation movement to efforts to shut down fascist student organizations—and overseas in the Smash EDO campaign. All this, plus obscure Russian history, a reappraisal of the concept of “free speech,” and the usual stunning prose. No advertisements; 16 full-color pages.

We’ve taken this opportunity to add Rolling Thunder #12 (the most current issues) to the Rolling Thunder Bundle, now containing issues #8, #10, #11, and #12 for just $10. And, don’t forget, you can subscribe to Rolling Thunder to get future issues hot off the press, while also supporting the project and ensuring the journal’s continued existence. Our current plan is to release issue #13 this spring.

January 8, 2016

The Ex-Worker #45: 2015 Year in Review!

#44: 2015 Year in Review! In our first episode of the new year, the Ex-Worker looks back over 2015 and its highlights, lowlights, and everything in between. We summarize some of the year’s key news developments, including tech developments and struggles around gender, anarchist publishing and media, a hilarious look at mass media coverage of anarchism, and our reflections on the last year of the podcast itself and our new year’s resolutions. You’ll also hear some analysis of some of the important themes within anarchism and revolutionary struggles in 2015, including an extended discussion on identity and solidarity, a review of the AK Press anthology “Taking Sides”, and reflections on our relationship to mass movements. The anarchist news website “It’s Going Down” contributes their end of year thoughts, a new project called “The Spaces Between” sets out to document US anarchism outside of its major urban hotspots, and a supporter offers an important update on NATO 3 prisoner Jared “Jay” Chase. We also received a number of detailed and inspiring year in review reports from anarchists around the world… but we’ll save those for our next episode.

You can download this and all of our previous episodes online. You can also subscribe in iTunes here or just add the feed URL to your podcast player of choice. Rate us on iTunes and let us know what you think, or send us an email to podcast@crimethinc.com. You can also call us 24 hours a day at 202–59-NOWRK, that is, 202–596–6975.

December 28, 2015

#44: TCE International Panel Discussion

#44: To Change Everything – International Panel Discussion – In our 44th episode of the Ex-worker, and our final episode of 2015, we bring you a live audio recording from the last stop of the recently wrapped-up To Change Everything tour, an international panel discussion featuring stories and lessons from participants in some of the better and lesser known uprisings of the last few years. In two months and just over 50 stops, the featured speakers—hailing from Slovenia, Brazil, the Czech Republic and the U.S.—presented their perspectives on topics ranging from the common pitfalls of making demands, the rise of nationalism and fascism, and the importance of solidarity in the face of state repression. Stay tuned to the end of the episode where we propose some ideas for maintaining some of these valuable, face-to-face connections that have been made while on the tour. In addition, we’re releasing this episode in conjunction with the full tour report-back, so make sure you check that out as well.

You can download this and all of our previous episodes online. You can also subscribe in iTunes here or just add the feed URL to your podcast player of choice. Rate us on iTunes and let us know what you think, or send us an email to podcast@crimethinc.com. You can also call us 24 hours a day at 202–59-NOWRK, that is, 202–596–6975.

December 14, 2015

The French 9/11

We participated in the following dialogue with members of the French news source Lundimatin, comparing the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attacks in the United States with the situation in France today. This interview is available in French on their site.

Bonjour, France, and welcome to team War on Terror! For fourteen years, you’ve looked askance at us across the Atlantic, raising your eyebrows at US foreign policy. Now you get to have your own state of emergency, your own far-right party in power, your own warrantless wiretapping and waterboarding scandals and Department of Homeland Security. Where will you put your Guantanamo Bay? (Finally, French fries and Freedom fries will mean the same thing!) For maximum effect, consider starting a new war that has nothing to do with the cause of the attacks, so you can destabilize another region and draw additional populations into the conflict.

We Americans know all about this stuff. For decades now, the US has been the policeman of the world, while social democratic France has been its comfortable bourgeoisie. But in the 21st century, everyone has to take part in policing. To preserve France, the liberal alternative to the US, it is now necessary to copy the US model of anti-terrorism. Permit us to show you the ropes.

December 7, 2015

Ex-Worker #43: Borders and Migration, Part I

#43: Borders and Migration, Part I: Europe’s “Refugee Crisis” – One of the major news stories of 2015 has been the flow of hundreds of thousands of migrants from Syria and beyond into Europe, and the social and political crises this has precipitated. In Episode 43 of the Ex-Worker, we take a look at Europe’s so-called refugee crisis from an anarchist perspective. This episode adopts a “mix tape” format, pasting together excerpts from a variety of sources to offer an impressionistic look at how and why people move across the world, the barriers thrown up by states to impede and control them, and popular resistance against the system of national borders. We begin with reflections from the CrimethInc. Contradictionary, To Change Everything, and past Ex-Worker episodes on borders and continue with excerpts from interviews with No One Is Illegal activist Harsha Walia, author Vijay Prashad, and a Swiss anarchist active in migrant solidarity struggles in Europe, as well as essays from an activist convergence against climate change, Calais Migrant Solidarity, and Mask Magazine’s “Asylum” issue; and conclude with reflections on the Islamic State attacks in Paris from the CrimethInc. blog. You’ll also hear updates on anti-anarchist repression in Spain and anti-government demonstrations in South Korea, a report-back from the Rebel! Rebuild! Rewild! action camp in eastern Canada, and an announcement for a new prisoner publication, plus news, upcoming events, and more, in one of our most packed episodes yet!

You can download this and all of our previous episodes online. You can also subscribe in iTunes here or just add the feed URL to your podcast player of choice. Rate us on iTunes and let us know what you think, or send us an email to podcast@crimethinc.com. You can also call us 24 hours a day at 202–59-NOWRK, that is, 202–596–6975.

November 25, 2015

Letter from Paris

We received the following report from the group that produced the French version of To Change Everything, Pour Tout Changer. They describe the situation in Paris before and after the attacks of November 13: the intensification of xenophobic discourse, the repression of homeless refugees, the declaration of a “state of emergency” as a way to clamp down on dissent, the preparations for the COP 21 summit at which demonstrations are now banned, and what people are doing to counter all this. It offers an eyewitness account from the front lines of the struggle against the opportunists who hope to use the tragedy of November 13 to advance their agenda of racism and autocracy. With demonstrations forbidden and the COP 21 summit around the corner, what happens in Paris will set an important precedent for whether governments can use the specter of terrorism to suppress efforts to change the disastrous course on which they are steering us.

Escalating Xenophobia

The attacks that took place in Paris several days ago, tragic as they are, are unfortunately not an isolated event. The capital city of France was simply another target in a string of bombings in Suruç, Ankara, and Beirut; it represents the continuation and expansion of the strategy ISIS initiated in the Middle East.

In France, these attacks exacerbate a political context that was already fraught. Following the attacks of September 11, 2001 and the participation of the far-right party Front National in the second round of the 2002 presidential election, the political discourse has taken an increasingly conservative tone. For example, Nicolas Sarkozy, as Ministre de l’Intérieur from 2002 to 2007 and President from 2007 to 2012, openly adopted some arguments, topics, and symbols that were previously only used by the Front National. These discourses of “identity” and “security” have especially stigmatized Arabic and Muslim communities. In 2010, for example, a law was passed stipulating that it was forbidden to cover your face in public places in France. While not explicitly directed at those wearing a niqab or hijab, it resulted in more controls targeting Muslim women.

During this same time period, law enforcement groups were given new equipment such as Flash-balls (supposedly non-lethal anti-riot weapons) and Taser guns. The national DNA file, used since 1998 to collect the DNA of sexual offenders and abusers, has been extended to every person convicted of an offense. The “Plan Vigipirate,” a governmental anti-terrorism security plan established in 1995 after several bombing attacks in France, was also updated three times between 2002 and 2006, and more recently in 2014 under current President François Hollande.

Before the Attacks

For years, refugees have been fleeing their countries to escape death, military conflicts, and constant political instability. Until last summer, the French government and its European counterparts didn’t care about the refugee issue—witness the countless tragic deaths of people trying to cross the Mediterranean sea. In Paris, several groups of refugees have been living on the streets in precarious conditions for months.

Nevertheless, due to accelerating waves of immigration, the French government started to change its policy, taking part in the European political initiative “Welcome Refugees.” This was more of a political move than an expression of solidarity. During this period, refugees and migrants, left alone by authorities, began to create their own camps in several locations in Paris. They received some assistance from NGOs, collectives, activists, and others concerned about their difficult situation.

However, refugees faced aggressive state repression, as they still do. They are regularly harassed by police who intimidate, beat, evict, and arrest them or destroy their camps. In June 2015, the fascist group Génération Identitaire (Identity Generation) attacked a refugee camp in Austerlitz with stones and bottles. The Austerlitz camps were removed by the authorities in September.

At the end of July, another group of refugees and migrants decided to squat an old and abandoned high school in the 19th district of Paris: the Lycée Jean Quarré. Collectives and activists came to offer help; together, they began organizing demonstrations to defend refugees’ rights. On the morning of October 23, police evicted the squat. Some of the migrants who occupied it have been relocated to centers or shelters in the suburbs or even further outside Paris. Others remained without a place to sleep, so they camped in front of the Hotel de Ville, the City Hall of Paris.

Police officers and migrants at the squatted Lycée Jean Quarré.

The day after the eviction, demonstrations were planned at the same time in England and in France under the slogan of “Freedom for the three migrants imprisoned in England—Papers and housing for all—Freedom of movement, no borders.” At the end of the demonstration, some refugees were determined to block the streets until the Mayor found a solution to relocate everyone. They occupied a major intersection for approximately 45 minutes. Then, as usual, police showed up in riot gear. After discussing the possible consequences, the participants shifted to occupying a nearby theater. As they were forcing the doors, the police charged in a surprisingly disorganized and chaotic manner. Some demonstrators continued to confront the police as they were pushed back to a main street.

A few hours after the demo, some refugees and migrants, still without a place to sleep for the night, occupied the Place de la République, one of the major squares in downtown Paris. Since that day, they have been evicted several times and their camps and personal belongings have been destroyed and seized by the police. Several gatherings took place to help refugees and defend the square against eviction. The tension was always high during those actions and police forces were numerous. A few weeks ago, at one such gathering, an Afghan refugee explained to us that he and some of his friends have finally received housing for at least six months. Nevertheless, he also told us that newer refugees who had just arrived from Germany would sleep outside in the camp that night. On Friday, November 13, the police evicted the camp again just a few hours before the ISIS attacks took place in the same district.

At the same time, the authorities have been directing increasing surveillance towards anarchists and their spaces. Several anarchists have recently been arrested in the Paris area, demonstrating the European common political agenda of increasing repression against anarchists—as we have seen recently, on a larger scale, in Greece, Spain, and even Czech Republic. Members of La Discordia, a new anarchist library in the 19th district of Paris that opened in spring 2015, published an article in October showing that the police were monitoring and recording their activities. A device was found hidden in a room at the school facing the library, as its director had agreed to assist the police in their surveillance.

Meanwhile, the COP 21 was coming up. From November 28 to December 12, politicians from around the world will gather in Paris to pretend to discuss environmental issues; several demonstrations and events were planned by worldwide organizations to oppose this international masquerade. An appeal to participate to the anti-COP 21 in Paris has appeared in several languages and Paris is expecting an international mobilization.

The French government took steps to control and contain popular opposition even before the November 13 attacks. First, they decided to close the borders: contrary to ordinary Shengen practice, France will enforce border controls and refuse some people entry. The government has also refused visas to foreign activists and members of organizations. Furthermore, the police administration sent a message to all their employees at a national level asking them not to take vacations during the COP 21 in case they need to mobilize everyone against activists and “black blocks” (French media and politicians still misunderstand black blocs to be a distinct organization, not a reproducible tactic). In other words, the authorities fear that this international meeting will occasion fierce resistance.

After the Attacks

As soon as the attacks took place, and especially when people were taken hostage at the Bataclan, a major venue, Paris became an “urban warfare” zone: police forces were on alert everywhere along with special forces and tactical groups, while soldiers, emergency personnel, and firemen blocked all the streets around the sites of the attacks. Everyone in these areas was searched, had their IDs checked, and told to leave the streets and go home. Those who were at bars were forced to stay inside for hours before police ordered them to leave, some with their hands on their heads. In the moment, the violence of the images and events let us speechless, confused, and scared—not only about the attacks but even more so about what would come next.

Paris the night of the attacks: the army takes the streets.

Shortly afterwards, President François Hollande made an official statement on television saying that France was now at war against the terrorists, against ISIS. Hollande used the same rhetoric and vocabulary George W. Bush did in his speech after September 11, 2001. Hollande also explained that France was now increasing its emergency alert level to just below the ultimate level of war within the French territory. In the name of the “state of emergency” and in order to reinforce and maintain national “security,” Hollande asked to deploy about 10,000 soldiers to help police officers carry out surveillance and control.

The “state of emergency” is a peculiar law passed on April 3, 1955 that provides civil authorities of a specific geographical area with exceptional police powers to regulate people’s movement and residence, close public places, and requisition weapons. It enables the authorities to take all the decisions they want and to drastically reduce liberties and freedom. This law was created and used primarily during the war against Algeria. Between 1955 and 1961, the “state of emergency” was imposed several times on the Franco-Algerian territory. Later, it was used in New Caledonia in 1984-1985. Finally, and for the first time in the French metropolis, the state of emergency was imposed in 2005 after the uprisings that took place in our suburbs.

Once applied, this state of emergency can take several forms. The President and prefects can use it to impose curfews on their population. Car traffic can be forbidden in certain districts or zones at specific hours. Prefects can determine where people are permitted to go, establishing restricted areas and safety zones and even forbidding someone from going to or living in a specific zone if that person is considered a threat. Indeed, every person considered “dangerous” can be forced to stay at home without any option of going out, or only allowed to go out within extremely precise conditions such as being monitored by an electronic bracelet. Movie theaters, venues, or any other place where people gather like bars and restaurants can be forced to close. Police officers can stop and check you without a specific reason—something they already do anyway—and any opposition can be considered a threat. Demonstrations, marches, and gatherings can be forbidden; searches and house raids can be made day and night without warrants; every single person who contests this situation can be punished with financial charges or prison according to stipulations built into the “state of emergency” legislation.

During the three days of national mourning imposed by François Hollande, the government made their first decisions responding to the attacks. First, they decided to increase their military strikes on ISIS positions in Syria; they are trying now to form a coalition with the US, Great Britain, Germany, and Russia to wage a total war against “terrorism.” Then our Assemblée Nationale, the official building where our deputies discuss and make laws, voted almost unanimously (551 pros vs. 6 cons) to extend the “state of emergency.” Now it will last three months, until February 26, 2016. Of course, it could be extended again after that.

Moreover, the government decided to keep the COP 21 in Paris—at least its official meeting and discussions—but forbade the demonstrations and activities organized by anti-COP activists. This can be seen as an attempt to muzzle the people taking part in the social movement to counter these meaningless meetings and political negotiations. It is also interesting to note, considering the three-month extension of the state of emergency, that in 2016, the construction of the new airport at Notre Dame des Landes is scheduled to resume—the airport that has thus far been blocked by the occupation known internationally as la ZAD. The authorities might try to control the opponents of the airport under this supposedly “exceptional” law.

During the past few days, the authorities have made some other major decisions: starting now, our police officers are allowed to keep their weapons with them even after working hours in the name of national safety. The government has also asserted a closer surveillance of online activity. In addition, President François Hollande is trying to add new elements to the law governing the state of emergency, including policies such as stripping French citizenship from people recognized as a threat to national security, or closing mosques preaching a conservative interpretation of Islam.

People gathering at the Place de la République after the attacks.

Dark Days, Unwritten Futures

In the aftermath of the Paris’ attacks, we are sure to face even darker days than before between the increasing power of the government, the crushing of our liberties, and intensifying xenophobic and racist discourses among politicians and part of the population. Indeed, only a few hours had passed after the attacks before the first racist attacks took place in several towns around France. For example, on Saturday, November 14 in Pontivy, Brittany, while taking part in a demonstration, members of “Adsav,” a fascist group defending Breton identity, beat an Arabic man. The weekend following the attacks in Paris, mosques were tagged with red Christian crosses and racist sentences; some Halal butcheries have also been targeted. In Marseilles, a Jewish professor and a woman wearing a headscarf were assaulted.

Adsav demonstrating in Pontivy on Saturday, November 14.

The attacks also reinforced French nationalism. The “Marseillaise,” the French national anthem, has been sung during many gatherings since the attacks; the national flag has been ubiquitous, even on social media profile pictures. All this nationalist momentum produced a spike in applications to join the French military, as some recruiters explained to journalists. All these events offer a great opportunity for the Front National to increase its influence once more across the French political spectrum, and to gain more electors during the municipal elections in December.

It is alarming how readily the majority of the French population accepts the policies of the “state of emergency” and the restriction of their movement and liberties. For anarchists and activists, these emergency measures raise several questions: What will happen if we violate the state of emergency by demonstrating? How will the police forces react? Will the government end up using this “exceptional law” to repress anarchists and other radical activists and carry out mass arrests? One thing is certain: since the attacks of the past January in Paris, most of the police forces haven’t been able to take vacations due to a lack of personnel. Some high-ranking members of the police explain that their troops are exhausted and on edge, which means that the tension during future actions including the COP 21 protests will be extremely high.

Nevertheless, it is important to remember that nothing is ever written in advance. As individuals, we have the capacity to make choices that could change the current inertia of the world.

On Sunday, November 22, several hundred people gathered in the Place de la Bastille to express solidarity with refugees and to contest the “state of emergency” declared by the government, despite the gathering having been prohibited following the attacks. When we arrived, police forces were present but were standing back from the increasing group of activists. We took this opportunity and started walking in the middle of the road, determined to demonstrate no matter what. Police forces ran after us, faced us in a line, and tried to turn us away from our principal objective of taking a major boulevard to reach Place de la République. Their first attempt failed, as some activists got around the police line and kept walking on the boulevard, chanting “Solidarity with all refugees!” There followed a chase between police and activists. At one time, they succeeded splitting us in two groups, and clashes broke out as people tried to break through their lines of separation. They answered with tear gas and truncheon blows. Nevertheless, their attacks didn’t stop us. In the end, we succeeded in breaking their lines, and once again we were demonstrating together, heading to our objective. Finally, after approximately 30 minutes marked by clashes with the police, we arrived at the Place de la République, which was full of people who had come on that Sunday afternoon to lay flowers and pay homage to the victims of the attacks.

The protests of November 22 in Paris.

The success of this spontaneous demonstration in defying the “state of emergency” shows that we can still act on our own strength, refusing to surrender to the general state of fear and to the new laws imposed in the name of national security. More than ever, we must help and take care of each other, we must keep organizing, we must stay focused and continue defying authority. This is what we should keep in mind as the COP 21 will start in few days in Paris. The struggle continues.

November 17, 2015

The Borders Won’t Protect You

In Paris, on November 13, 129 people were killed in coordinated bombings and shootings for which the Islamic State claimed responsibility. European nationalists lost no time seeking to tie the attacks in Paris to the so-called migrant crisis, even though many of the refugees are fleeing similar attacks orchestrated by ISIS.

Tighter border controls won’t protect us from attacks like the one in Paris, though they will go on causing migrant deaths. Airstrikes won’t stop suicide bombers, but they will produce new generations that nurse a grudge against the West. Government surveillance won’t catch every bomb plot, but it will target the social movements that offer an alternative to nationalism and war. If the proponents of Fortress Europe succeed in suppressing and segregating us, we will surely end up fighting each other: divide and rule. Our only hope is to establish common cause against our rulers, building bridges across the boundaries of citizenship and religion before the whole world is carved up on the butcher’s block of war.

CrimethInc.'s Blog

- CrimethInc.'s profile

- 267 followers