CrimethInc.'s Blog, page 2

September 21, 2016

To Change Everything in 11 More Languages

We are pleased to present versions of To Change Everything in Arabic, Armenian, Bulgarian, Cebuano, Dutch, Farsi, Malay, Maltese, and Serbo-Croatian, as well as the Latin American Spanish version and subtitles for the video in Tagalog and Slovak. This brings the grand total to 30 versions of the project in 28 languages.

In addition, we’ve added updated PDFs of the continental French, Italian, Portuguese, and Slovenian versions.

If you are interested in producing a version of To Change Everything for your own language or region, please contact us.

We are also pleased to announce new print runs in several languages, including Dutch, Malay, Serbo-Croat, and 500 copies for the islands of Malta. After an initial print run of 5000 copies of the Portuguese version, the Brazilian group has produced a run of 11,000 more, funded in part by last year’s “To Change Everything” tour in the US; a new German printing is soon to appear, bringing the total print run in Germany to 50,000. Comrades involved in solidarity efforts in Europe have been making the Arabic and Farsi versions available to migrants seeking to escape oppression, war, and economic turmoil.

Our next update will include the Spanish version of “The Secret Is to Begin”, the follow-up to To Change Everything.

العربية / Arabic

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [23MB]

Screen PDF (Spread View) [23MB]

Print PDF (B&W, Imposed) [18MB]

հայերեն / Armenian

Screen PDF (Spread View) [6MB]

Български / Bulgarian

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [15MB]

Screen PDF (Spread View) [15MB]

Print PDF (B&W, Imposed) [10MB]

Cebuano and Tagalog

Screen PDF (Spread View) [21MB]

*The pamphlet is in Cebuano; the video is in Tagalog.*

Español para América Latina / Latin America

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [31MB]

Screen PDF (Spread View) [14MB]

Nederlands / Dutch

Screen PDF (Spread View) [4.7MB]

فارسی / Farsi

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [24MB]

Screen PDF (Spread View) [23MB]

Print PDF (B&W, Imposed) [10MB]

Malay

Screen PDF (Reduced File Size, Spread View) [1MB]

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [21MB]

Malti / Maltese

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [2MB]

Screen PDF (Spread View) [2MB]

Srpskohrvatski / Serbo-Croatian

Screen PDF (Single Page View) [1MB]

Screen PDF (Spread View) [1MB]

Print PDF (B&W, Imposed) [16MB]

Slovenčina / Slovak

September 7, 2016

#50: The History and Future of Prison Strikes

#50: The History and Future of Prison Strikes and Solidarity — As we build momentum towards the September 9th national prison strike, we want to reflect on lessons learned from past generations of prison rebels, as well as how we can maintain energy on September 10th and beyond. In Episode 50 of the Ex-Worker, solidarity organizer Ben Turk fills us in on some history of prisoner organizing in recent decades, recaps some of the solidarity actions that have taken place leading up to this year’s historic strike, and offers perspective on continuing and deepening our resistance to prison society. We commemorate the death of Jordan MacTaggart, an American anarchist killed on the front lines in battle with the YPG against the Islamic State, and discuss international solidarity and the politics of martyrdom with Rojava Solidarity NYC. The death of John Timoney, former police chief and notorious foe of anarchists, prompts both glee and a somber reflection on the misery he inflicted on us. A member of Revolutionary Anarchist Action (DAF) in Istanbul discusses the background to the recent failed military coup as well as recent waves of anti-anarchist repression. A call for solidarity from la ZAD, news, events, and prisoner birthdays round out this packed episode.

You can download this and all of our previous episodes online. You can also subscribe in iTunes here or just add the feed URL to your podcast player of choice. Rate us on iTunes and let us know what you think, or send us an email to podcast@crimethinc.com. You can also call us 24 hours a day at 202–59-NOWRK, that is, 202–596–6975.

August 30, 2016

A Fitting End: The Death of John Timoney

John Timoney is dead. “The world has lost a great man and a law enforcement giant,” says the Police Chief of Ferguson, Missouri, who learned his trade under Timoney in Miami. Well, that’s one perspective. For myself and many others across the world, his death is a relief. It would have been better if he had never been born.

Timoney held positions in the upper echelon of the law enforcement world for nearly thirty years. He was First Deputy Commissioner of the New York City Police Department, Police Commissioner of Philadelphia, Police Chief of Miami, and finally, private consultant to the kingdom of Bahrain. He played a major role in the repression of social movements in the United States during the summit protest era of the late nineties and early aughts, and a significant role in the suppression of the Arab Spring nearly ten years later. Those of us who were active in these movements came to know his methods well.

I am one of the countless people who suffered at the hands of John Timoney and the police he commanded. Although sixteen years have passed, I still prefer to tell this story anonymously.

Timoney’s police in action during the FTAA protests of November 2003.

Timoney oversaw the police responses to the occupation of Tompkins Square Park in New York City in 1988, the protests against the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in 2000, the World Economic Forum in New York City in 2002, the Free Trade Area of the Americas Summit in Miami in 2003, and the Bahraini uprising from 2011 to 2013. His calling cards were undercover infiltration of movement spaces, preemptive mass arrests, and the use of the courts as a tool to neutralize dissent.

In the United States, he won important tactical victories in Philadelphia and Miami. In the streets, he liked bikes, clubs, and the liberal application of tear gas—and he knew how to keep the blood out of sight of the cameras. In court, he favored huge bails and trumped up charges against protesters. He perjured himself shamelessly, and he lost every case in the end. He truly hated anarchists, and by treating us just short of enemy combatants he toughened us up for the battles to come.

In August of 2000, I was arrested in Philadelphia along with 420 others during the protests against the Republican National Convention. The policeman who arrested me cuffed my hands behind my back with heavy plastic zip-ties. He was a large man, and I think it’s fair to say that he tightened them down as hard as he possibly could. He then put me into the back of a police van along with fifteen other people. We were each cuffed with our hands behind our backs and chained down to the bench of the van. Someone in the front of the vehicle turned the lights off in the back, turned the heat up full blast, and left. We sat there in the sweltering heat for something between four and six hours.

We spent those hours struggling to support each other, trying not to be consumed by fear and panic. This was during the hottest days of summer. The heat got so extreme and the ventilation was so poor that people were passing out from the bad air. Several people were bleeding as well—myself included. Worst of all, in my particular case, it seemed entirely possible that I was going to lose both of my hands from loss of blood circulation.

At first, the pain became so extreme that I would scream if anything touched me. Then the pain gave way to a complete loss of feeling. The two people on either side of me were able to reach me if I turned my back to one of them or the other. They took turns massaging my hands ceaselessly. Eventually, though, no matter how hard they tried, I couldn’t feel anything at all. When I asked what my hands looked like, I heard fear in their voices. It was not possible for either of them to reach the cuffs with their teeth to chew through the plastic.

Many people in this van were in a bad state, but my hands were probably the single worst thing going on. These hours tested my sanity, and it was very difficult not to succumb to panic. Nothing can really describe how terrified I was that I would spend the rest of my life as a double amputee. My companions sang to me.

Timoney’s stint in Bahrain was a fitting end to his career. It was the culmination of everything that he had done before, and his crimes against the Bahraini people are conspicuously absent from the obituaries that have appeared lauding him.

The Bahraini monarchy was the first American-backed government in the Middle East to demonstrate that it was not going to be toppled by civil resistance during the Arab Spring; the Assad regime in Syria was the first Russian-backed government to do so. The rationale for giving uncompromising support to these backward and repressive governments was the same on both sides: there is an American naval base in Bahrain and a Russian naval base in Syria. In both cases, the only options left open to the opposition were surrender or civil war. In Bahrain, the opposition eventually chose the former; in Syria, the latter, with notorious results.

Narrowing the field of possibilities down to this choice was John Timoney’s real life’s work. He was just never able to carry his vision through to its logical conclusion inside of the United States. His tactics were very effective at demobilizing people who weren’t ready to go to prison. They helped to bring about a world in which the only people with any agency appear to be those who are ready to die. Those who make peaceful revolution impossible make violent revolution inevitable, as John F. Kennedy put it long before the heyday of suicide bombings and mass shootings. The longer you suppress revolt, the uglier it is likely to be.

It’s not easy to ascertain all the ways Timoney served the Bahraini monarchy, or what his personal role was in the widespread torture and murder of dissidents there. But one thing is certain: in lending a hand to suppress the Arab Spring, he left his fingerprints all over the current mayhem in Syria and Iraq.

Eventually, the police moved the van to the location where we were to be processed. After what felt like an eternity, they finallyopened the door. I was bordering on hallucination by this time. Numerous people began vociferously explaining to the guards that it was of dire urgency that my cuffs be removed. One of the guards unchained me from the bench of the van. I literally saw his jaw drop when he looked behind my back. He cut the cuffs off immediately. Both of my hands were a deep black-purple from the wrists to the fingertips.

It took a number of days for me to regain the normal use of my hands. Thankfully, I did recover fully. I think it’s likely that I only avoided permanent injury because of the actions of the two people next to me in the van. I still have the scars to show for this ordeal, although they have faded with time. I’m sure the policeman who cuffed me has long ago forgotten the incident. I remember.

Timoney usually won the battle. It looks like he lost the war. If his primary objective was to preserve the status quo, then he failed. Only sixteen years ago, the institutions that he represented seemed omnipotent and eternal. Now they are all in an advanced state of decomposition, like Timoney himself.

The Republican Party is in complete disarray. Free trade policies are coming under fire from both ends of the political spectrum. The police have probably never faced such widespread condemnation. The Middle East is metastasizing chaos in every direction, and not in a good way. It’s only a matter of time before it reaches Bahrain.

None of this is really what we were hoping for. It’s hard to be excited about the old world falling apart when the present is such a mess and the future looks so bleak. Even those who opposed us a decade and a half ago must acknowledge that the proposals we were offering at that time were preferable to the crises that have become inevitable thanks to our defeat.

Nevertheless, we’re still here. We’re going to be all right. Although our new enemies are fearsome indeed, it’s good to remember that they too are mortal. Sixteen years ago, as hundreds of traumatized protesters faced charges from the Republican National Convention, it felt as though Timoney and his ilk would reign forever. In fact, all it takes to see our oppressors destroyed is to live long enough.

August 16, 2016: John Timoney, dead of lung cancer at 68. We got to write his obituary. He was never able to write ours.

Some of our bails were set as high as one million dollars; some of us faced an array of charges amounting to life in prison. Some of these cases dragged on for nearly four years. In the end, every single one of the 420 people who were arrested during the demonstrations was either acquitted or had the case thrown out of court. None of us testified against each other. Not one of us was ever convicted of any crime.

My story is only one of many. In Philadelphia, I met people who had been waiting to go to trial for three years in Timoney’s jails, many of them for non-violent drug-related offenses (like those for which Timoney’s own children are known). I saw police and guards beat handcuffed detainees. They knew how to keep it away from the cameras. I’ve heard countless accounts like mine from Miami. I can’t imagine what people in Bahrain went through.

On August 16, I heard the news and I couldn’t have been happier. John Timoney is dead. The struggle continues.

The more of this, the better for everyone.

In memory of Jordan MacTaggart, killed in action August 3, 2016 in Manbij, Syria, fighting a monster that John Timoney helped to create. In return for his courageous sacrifice, the US government betrayed MacTaggart’s comrades the moment they had fulfilled the US agenda. There is no honor in the institutions Timoney served and no safety in the order they seek to impose, but we will have to clean up the messes they make. Timoney was no hero. MacTaggart is.

August 24, 2016

#49: September 9th National Prison Strike

#49: September 9th National Prison Strike — The Ex-Worker is back! And just in time, because a potentially historic national prisoner strike is just around the corner. In our 49th episode, we discuss the upcoming September 9th strike to end prison slavery, with an interview with the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee. You’ll also hear a review of Dan Berger’s book Captive Nation: Black Prison Organizing in the Civil Rights

Era; an interview with an anarchist from the UK about the Brexit vote; listener feedback on Spanish revolutionary militias, Comintern, and parallels with Rojava; updates on Kara Wild, a trans anarchist incarcerated in Paris; a letter from trans anarchist prisoner Jennifer Gann; plus news, prisoner birthdays,

event announcements, and plenty more.

You can download this and all of our previous episodes online. You can also subscribe in iTunes here or just add the feed URL to your podcast player of choice. Rate us on iTunes and let us know what you think, or send us an email to podcast@crimethinc.com. You can also call us 24 hours a day at 202–59-NOWRK, that is, 202–596–6975.

June 23, 2016

The Democracy of the Reaction, 1848-2011

What harm could possibly come of using the discourse of democracy to describe the object of our movements for liberation? We can answer this question with a fable drawn from history: the story of the uprising that took place in Paris in June 1848.

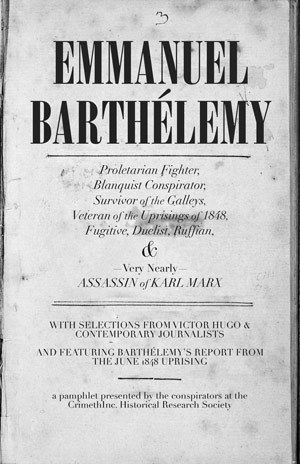

In addition, to commemorate the June 1848 uprising, 168 years ago this week, we’ve prepared a biography of one of its many colorful participants, including the first translation into English of the only surviving account from the proletarian side of the barricades.

David Graeber has drawn parallels between the revolutions of 1848 and the uprisings of 2011. None of the revolutionary movements of 1848 managed to hold power for more than a couple years. Yet the basic goals that they fought for were widely achieved within a few decades: everywhere, monarchies were giving way to constitutional democracies, with universal suffrage and social safety nets on the way. The argument by analogy is that, though the uprisings that peaked in 2011 were not immediately successful, they will have a long-term impact on how we think about politics. The struggles for state democracy in the Middle East and Southeast Asia and the experiences of directly democratic movements in Europe and the US created a situation in which people around the world are bound to demand more democracy in their governments and their lives.

Perhaps. But this framework doesn’t offer us any tools with which to understand how the reactionary forces that suffered setbacks in 1848 and 2011 could reconfigure themselves under democratic banners. In Egypt, after the revolution of 2011, the idea of democratic government re-legitimized the apparatus of state repression long enough for the military to return to power. In Europe and the US, the momentum of directly democratic grassroots movements was channeled into political parties like Syriza and Podemos and the doomed candidacy of Bernie Sanders.

In fact, what happened in Egypt between 2011 and 2014 is a lot like what happened in France between 1848 and 1851. A wide-ranging coalition of different groups overthrew a dictator; the most conservative elements in the coalition won the elections; the resulting popular uprisings were repressed in the name of protecting the fledgling democracy; and in the end, a new despot came to power through a combination of election and coup. The reemergence of the Deep State in France in June 1848 and in Egypt in 2013 underscores why anarchists have argued ever since 1848 that the only sure way to hold on to revolutionary gains is to delegitimize and disarticulate the state. The problem with democratic discourse is that, because the vast majority of democratic models are state-based, it offers cover to anyone who wants to relegitimize state power. Indeed, even those who explicitly oppose the state can end up reinforcing it—whether by joining the government, as anarchists from the CNT did during the Spanish Civil War, or more obliquely, by legitimizing frameworks and objectives that ultimately enable partisans of the state to present themselves as the ones with the most effective strategy, as anarchists like Cindy Milstein and David Graeber risk doing.

To understand how this works, let’s go back to 1848.

In February 1848, an uprising in Paris toppled the king; revolt radiated throughout Europe along with the news of the French revolution, spreading faster than any wave of unrest in the digital age. The transformation of France into a Republic occasioned much rejoicing, but there was little agreement as to what a Republic was. Just as anarchists, socialists, liberals, neoconservatives, and fascists rub shoulders under the banner of democracy today, in 1848 a vast range of people identified with the ideal of the Republic, confining themselves to debates about what the true nature of the Republic might be. Even Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, already a self-professed anarchist, called himself a Republican, and his explicit opposition to authority didn’t stop him from serving in the National Assembly alongside conservatives like Adolphe Thiers—the statesman who later butchered the Paris Commune in the name of the Republic.

Indeed, universal manhood suffrage, long sought by radicals, brought a predominantly reactionary government to power. Former monarchists and aristocrats reinvented themselves as Republicans and set out use their superior resources to game the system. All this illustrates why, once a goal is achieved, it’s best to dispense with the old rhetoric in favor of language that clarifies the new problems that arise. Today, we can’t imagine anarchists or other sincere proponents of freedom laying claim to the banner of the Republic, though many still present themselves as the champions of real democracy.

In June 1848, four months after the revolution, the newly elected government of the Republic rescinded the few steps it had taken to address the plight of the poor—and the workers who had risen up in February once again barricaded the streets of Paris and called for revolution. From the perspective of the good Republicans, this was unthinkable: they had finally achieved a democratic government, so anyone who revolted against it was an enemy of democracy. This time, the workers found no allies among middle-class Republicans. They were on their own.

Victor Hugo, elected to the National Assembly alongside Proudhon and Thiers, considered it his civic duty as a democrat and Republican to accompany the army as it stormed the city and gunned down the rebels. The reactionaries who had not been able to vanquish the workers in the name of the monarchy now slaughtered them in the name of the Republic, preserving the social order that had caused the revolution in the first place. Thousands were butchered in a three-day hail of lead. Afterward, many shops could not reopen because all the employees had been killed.

Shortly thereafter, Napoleon’s nephew was elected President of the Republic. At the end of his term, he organized a coup d’etat to establish himself as Emperor, bringing the brief reign of democracy to an end. This time, Victor Hugo implored the workers of Paris to build barricades and rise against the usurper, but they turned him a deaf ear. Why should they risk their lives to preserve the authority of the Republicans who had massacred them last time they rose against their oppressors?

Now that the Reaction had no more use for the politicians who had paved the way for it, they too were herded into prison and exile. Their elections and patriotism had served to maintain the legitimacy of the government just long enough for a shrewder tyrant to take the helm. Urging the poor to break the law in the name of the Constitution, Victor Hugo and his comrades showed the contradictions inherent in their lukewarm revolutionism.

With the novels he published from exile, Hugo earned worldwide acclaim for putting words in the mouths of the same poor people whose slaughter he had overseen. He wrote about the events of June 1848 in his memoirs, bewailing “on one side the despair of the people, on the other the despair of society,” sidestepping his role in the killings he described with such pathos. In Les Miserables, he struggled to make sense of how the people who had made the revolution could take up arms against its legitimately elected representatives:

“It sometimes happens that, even contrary to principles, even contrary to liberty, equality, and fraternity, even contrary to the universal vote, even contrary to the government, by all for all, from the depths of its anguish, of its discouragements and its destitutions, of its fevers, of its distresses, of its miasmas, of its ignorances, of its darkness, that great and despairing body, the rabble, protests against, and that the populace wages battle against, the people.

“It was necessary to combat it, and this was a duty, for it attacked the republic. But what was June, 1848, at bottom? A revolt of the people against itself… It attacked in the name of the revolution—what? The revolution. It—that barricade, chance, hazard, disorder, terror, misunderstanding, the unknown—faced the Constituent Assembly, the sovereignty of the people, universal suffrage, the nation, the Republic.”

In short, Victor Hugo sided with society against the people who comprise it; with sovereignty against liberty; with humanity against human beings. In the name of democracy and the republic, he hoodwinked himself into doing his part to preserve class society at the barrel of a gun. He wasn’t alone in this: Proudhon and nearly all the well-known socialists chose the government’s side of the barricades.

At the time, republican democracy was new enough to Europe that few could foresee how it might advance a reactionary agenda. The same is true of direct democracy today: it has occurred to very few people that a more participatory digital democracy might buttress the legitimacy of police and prisons. Graeber’s prediction—that the democratic aims of the movements defeated in 2011 will nonetheless be achieved in the years ahead—might be fulfilled without achieving any significant gains towards liberation, just as the agendas of the revolutions of 1848 were implemented in a repressive way by politicians like Adolphe Thiers who slaughtered the original revolutionaries in the process. The French Republic finally triumphed in 1871, with the massacre of tens of thousands of Communards; like the workers of June 1848, the generations of anarchists and communists that came after 1871 had to fight against the republican government without the assistance of those who had opposed the monarchy and the emperor. Contrary to Graeber’s optimism, the aspirations of 1848 were realized in letter but not in spirit—as too might the aspirations of 2011 be, unless we develop a critique of the democracy of the reaction.

How can we be sure not to repeat the tragedy of June 1848? First, we should never let a shift in the political sphere substitute for social and economic self-determination. Likewise, we should never become so enamored of a particular decision-making method—be it parliamentary democracy or consensus-run assemblies—that we can be induced to countenance injustice in its name. In every Occupy encampment in which middle-class participants used the general assembly to lord it over homeless occupants of the encampment, we can recognize an echo of June 1848. Finally, above all, we should always be thinking beyond our own victories, developing critical tools with which to tackle the problems that will arise afterwards—fighting the next war, not the last one.

Further Reading

To commemorate the uprising of June 1848, we’ve prepared a biography of one of its many colorful participants, Emmanuel Barthélemy. Vilified by Victor Hugo in the same chapter of Les Miserables quoted above, Barthélemy risked his life on the barricades, escaped from prison, and later fought a duel with a Republican who served on the National Assembly. Among other historical materials, we’ve tracked down and translated Barthélemy’s report on his role in the uprising. Although it is practically the only surviving account from the proletarian side of the barricades, this is the first time it has appeared in English.

Emmanuel Barthélemy

Online reading PDF [10MB]

Imposed Printing PDF [10MB]

Despite his uneven track record, Proudhon’s critical reflections on democracy, published at the outset of the 1848 revolution, are also of interest. For more on the anarchist critique of democracy, consult our series on the subject.

May 26, 2016

Democracy: The Patriotic Temptation

In this installment in our series exploring the anarchist critique of democracy, guest author Uri Gordon discusses the attractions and risks of democratic discourse.

Like most political words, democracy is an “essentially contested” concept—its meaning is itself a political battleground. What political ideologies do, as mass patterns of political expression, is to “de-contest” or fix the meaning of such concepts and place them in particular relationships. The term “equality,” for example, can mean equal access to advantage (liberalism), equal responsibility to the national community (fascism), or equal power in a classless society (anarchism). On such a reading, there is no way objectively to determine the meaning of such concepts—all that exists are distinct usages, each of them regularly grouped with other concepts in one or another ideological formation.

I would therefore like to suspend the discussion of the appropriate conceptual understanding of democracy, and instead ask about the strategic choice to employ the term. Is it worthwhile for anarchists to de-contest “democracy” in ways that point towards statelessness and non-domination? Two arguments follow. The first is that anarchist invocations of democracy are a relatively new and distinctly American phenomenon. The second is that the invocation is problematic, because its rhetorical structure and audience targeting almost inevitably end up appealing to patriotic sentiments and national origin myths.

Even the Most Democratic of Democracies…

Historically, democracy was not a word that anarchists tended to use in reference to their own visions or practices. A survey of the writings of the prominent anarchist activists and theorists of the 19th and early 20th century reveals that, on the rare occasions on which they even employed the term, it was used in its conventional, statist sense to refer to actually-existing democratic institutions and entitlements within the bourgeois state. Democracy meant representative government, as opposed to monarchy or oligarchy.

Proudhon clearly viewed democracy in these terms. In chapter 1 of What is Property he wrote:

The nation, so long a victim of monarchical selfishness, thought to deliver itself for ever by declaring that it alone was sovereign. But what was monarchy? The sovereignty of one man. What is democracy? The sovereignty of the nation, or, rather, of the national majority… in reality there is no revolution in the government, since the principle remains the same. Now, we have the proof to-day that, with the most perfect democracy, we cannot be free.

The issue for Proudhon is sovereignty as such, and not the question of who or what legitimates it. In chapter 7 of The Philosophy of Poverty he also objects to any “system of authority, whatever its origin, monarchical or democratic” (Proudhon 1847). At no point does Proudhon distinguish between “real” and “so-called” democracy; the term simply stands for government by representatives.

This approach persists through the anarchist tradition. Bakunin in Statism and Anarchy (1873:178) attacks Marxists who “by popular government… mean government of the people by a small number of representatives elected by the people… a lie behind which the despotism of a ruling minority is concealed, a lie all the more dangerous in that it represents itself as the expression of a sham popular will.” Alexander Berkman sounded a similar critique in the Mother Earth Bulletin of October 1917:

The democratic authority of majority rule is the last pillar of tyranny. The last, but the strongest… the despotism that is invisible because not personified, shears Samson of his passion and leaves him will-less. Woe to the people where the citizen is a sovereign whose power is in the hands of his masters! It is a nation of willing slaves.

Finally, Malatesta (1924) also treats “democracy” only in terms of a system of government:

Even in the most democratic of democracies it is always a small minority that rules and imposes its will and interests by force… Therefore, those who really want ‘government of the people’ in the sense that each can assert his or her own will, ideas and needs, must ensure that no one, majority or minority, can rule over others; in other words, they must abolish government, meaning any coercive organisation, and replace it with the free organisation of those with common interests and aims.

In all of these cases, there is no attempt to align anarchism with democracy, or to construe the latter on any terms other than those of conventional representative institutions. The association between anarchism and democracy makes its appearance only around the 1980s, through the writings of Murray Bookchin.

Bookchin’s disavowal of anarchism towards the end of his life is irrelevant here, since his statements regarding democracy had remained consistent since the late 70s, when they were couched in terms of a strategy recommended to anarchists. Echoing Martin Buber’s critique of the expansion of the “political principle” of top-down power and centralised authority at the expense of the “social principle” of horizontal and spontaneous relationships (Buber 1957), Bookchin sees the only promising avenue for resistance in “a recovery of community, autonomy, relative self-sufficiency, self reliance, and direct democracy” on the local level, fostering “social institutions that by their very logic, stand in sharp opposition to increasingly all pervasive political institutions” (Bookchin 1980). This vision is clearly one of an anarchistic localism, based on “free popular assemblies,” “collectivization of resources,” and strictly mandated delegation of administrative coordinators. The question remains, however: should this arrangement be promoted with the language of democracy—albeit direct and participatory? What is the appeal of such language in the first place?

Selling Anarchism as Democracy

Essentially, the association of anarchism with democracy is a two-pronged rhetorical maneuver intended to increase the appeal of anarchism for mainstream publics. The first component of the maneuver is to latch onto the existing positive connotations that democracy carries in established political language. Instead of the negative (and false) image of anarchism as mindless and chaotic, a positive image is fostered by riding on the coattails of “democracy” as a widely-endorsed term in the mass media, educational system, and everyday speech. The appeal here is not to any specific set of institutions or decision-making procedures, but to the association of democracy with freedom, equality, and solidarity—to the sentiments that go to work when democracy is placed in binary opposition to dictatorship, and celebrated as what distinguishes the “free countries” of the West from other regimes.

Yet the second component of the maneuver is subversive: it seeks to portray current capitalist societies as not, in fact, democratic, since they alienate decision-making power from the people and place it in the hands of elites. This amounts to an argument that the institutions and procedures that mainstream audiences associate with democracy—government by representatives—are not in fact democratic, or at least a very pale and limited fulfilment of the values they are said to embody. True democracy, in this account, can only be local, direct, participatory, and deliberative, and is ultimately achievable only in a stateless and classless society. The rhetorical aim of the maneuver as a whole is to generate in the audience a sense of indignation at having been deceived: while the emotional attachment to “democracy” is confirmed, the belief that it actually exists is denied.

Now there are two problems with this maneuver, one conceptual and one more substantive. The conceptual problem is that it introduces a truly idiosyncratic notion of democracy, so ambitious as to disqualify almost all political experiences that fall under the common understanding of the term—including all electoral systems in which representatives do not have a strict mandate and are not immediately recallable. By claiming that current “democratic” regimes are in fact not democratic at all and that the only democracy worthy of the name is actually some version of an anarchist society, anarchists are asking people to reconfigure their understanding of democracy in a rather extreme way. While it is possible to maintain this new usage with logical coherence, it is nevertheless so rarefied and contrary to the common usage that its potential as a pivot for mainstream opinion is highly questionable.

The second problem is graver. While the association with democracy may seek to appeal only to its egalitarian and libertarian connotations, it also entangles anarchism with the patriotic nature of the pride in democracy which it seeks to subvert. The appeal is not simply to an abstract design for participatory institutions, but to participatory institutions recovered from the American revolutionary tradition. Bookchin (1985) is quite explicit about this, when he calls on anarchists to “start speaking in the vocabulary of the democratic revolutions” while unearthing and enlarging their libertarian content:

That [American] bourgeois past has libertarian features about it: the town meetings of New England. Municipal and local control, the American mythology that the less government the better, the American belief in independence and individualism. All these things are antithetical to a cybernetic economy, a highly centralized corporative economy and a highly centralized political system… I’m for democratizing the republic and radicalizing the democracy, and doing that on the grass roots level: that will involve establishing libertarian institutions which are totally consistent with the American tradition. We can’t go back to the Russian Revolution or the Spanish revolution any more. Those revolutions are alien to people in North America.

Cindy Milstein’s formulation in her article “Democracy is Direct” (Milstein 2000) works directly to fulfil this program by seeking to build on American origin myths:

Given that the United States is held up as the pinnacle of democracy, it seems particularly appropriate to hark back to those strains of a radicalized democracy that fought so valiantly and lost so crushingly in the American Revolution. We need to take up that unfinished project… Like all the great modern revolutions, the American Revolution spawned a politics based on face-to-face assemblies confederated within and between cities… Those of us living in the United States have inherited this self-schooling in direct democracy, even if only in vague echoes… deep-seated values that many still hold dear: independence, initiative, liberty, equality. They continue to create a very real tension between grassroots self-governance and top-down representation.

The appeal to the consensus view of the American polity as founded in a popular and democratic revolution, genuinely animated by freedom and equality, is precisely intended to target existing patriotic sentiments, even as it emphasises their subversive consequences. Milstein even invokes Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address when she criticises reformist agendas which “work with a circumscribed and neutralized notion of democracy, where democracy is neither of the people, by the people, nor for the people, but rather, only in the supposed name of the people.” Yet this is a dangerous move, since it relies on a self-limiting critique of the patriotic sentiment itself, and allows the foundation myths to which it appeals to remain untouched by critiques of manufactured collective identity and colonial exclusion. While noting the need not to whitewash the racial, gendered, and other injustices that were part of “the historic event that created this country,” Milstein can only offer an unspecific exhortation to “grapple with the relation between this oppression and the liberatory moments of the American Revolution.”

Yet given that the appeal is targeted at non-anarchist participants, there is little if any guarantee that such a grappling would actually take place. The patriotic sentiment appealed to here is more often than not a component of a larger nationalist narrative, one that hardly partakes of a decolonial critique (which by itself would have many questions about the Western enlightenment roots of notions of citizenship and the public sphere). The celebration of democracy in terms that directly invoke the early days of the American polity may end up reinforcing rather than questioning loyalties to the nation-state that claims, however falsely, to be the carrier of the democratic inheritance of the colonial period. This is especially poignant in the context of the recent wave of mobilization, which displays precisely this mix of quintessentially anarchist-influenced means of organization and action, and distinctly patriotic and nationalist discourses—from the Egyptian revolution’s embrace of the military, through the Jeffersonian sentiments pervading the Occupy movement, and on to the outright nationalism of the Ukrainian revolution.

There is, indeed, one reason to question this concern—namely, the democratic and nationalist sentiments that have been expressed by movements with which anarchists have good reasons to sense an affinity. The most prominent of these are the struggles of communities in Chiapas linked to the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in southeast Mexico and the revolutionary movement in Rojava or Syrian Kurdistan. Both have not only employed the language of democracy to signify a decentralised and egalitarian form of society, but also an explicit agenda of national liberation. The Kurdish movement has publicly endorsed Bookchin as a source of inspiration. Does this mean that anarchists are wrong to maintain active solidarity with these movements? My answer is “No”—but due to a crucial difference that also vindicates the general argument above. It is not the same thing for stateless minorities in the global South to use the language of democracy and national liberation as it is for citizens of advanced capitalist countries in which national independence is already an accomplished fact. The former do not appeal to patriotic founding myths engendered by an existing nation state, with their associated privileges and injustices, but to the possibility of a different and untested form of radically decentralised and potentially stateless “national liberation.” To be sure, this carries its own risks, but anarchists in the global North are hardly in a position to preach on these matters.

Thus we return to the main point: for anarchists in the USA and Western Europe, at least, the choice to use the language of democracy is based on the desire to mobilize and subvert a form of patriotism that is ultimately establishment-friendly; it risks cementing the nationalist sentiments it seeks to undermine. Anarchists have always had a public image problem. Trying to undo it through the connection to mainstream democratic and nationalist sentiments is not worth this risk.

References

Bakunin, Mikhail. 1873. Statism and Anarchy, trans. Marshall S. Shatz (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990). (Online)

Berkman, Alexabder. 1917. Apropos. Mother Earth Bulletin 1.1. (Online)

Bookchin, Murray. 1980. The American Crisis II. Comment 1.5. (Online)

Bookchin, Murray. 1985. Radicalising Democracy (interview). Kick It Over 14. (Online)

Buber, Martin. 1957. Society and the State, trans. Maurice Friedman. In Pointing the Way (New York: Harper). Reprinted in Anarchy 54. (Online)

Malatesta, Errico. 1924. Democracy and Anarchy, trans. Gillian Fleming and Vernon Richards. In The Anarchist Revolution: Polemical Articles 1924-1931 (London: Freedom, 1995). (Online)

Milstein, Cindy. 2000. Democracy is Direct. In Anarchism and its Aspirations (Oakland: AK Press, 2010). (Online)

Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. 1840. What Is Property, trans. Benjamin Tucker. (New York, NY: Humboldt, 1890). (Online)

Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. 1847. The Philosophy of Poverty, trans. Benjamin Tucker (Cambridge ,MA: Wilson, 1888). (Online)

Rocker, Rudolf. 1937. Nationalism and Culture, trans. Ray E. Chase (St. Paul: Coughlin, 1978). (Online)

May 19, 2016

Rojava: Democracy and Commune

In the latest installment in our series exploring the anarchist critique of democracy, guest author Paul Z. Simons offers us a meditation on revolutionary forms of organization. Drawing on his experiences in Rojava in 2015, he contrasts conventional democratic practices with what he has seen of democratic confederalism and evaluates the federation of communes as a model for North American anarchists. At a time when the ruling order has been discredited but there are very few proposals for how else to shape our lives, Simons suggests some much-needed points of departure.

Lessons from Rojava, Part One:

Democracy and Commune; This and That

Democracy: “a system of government in which all the people of a state or polity… are involved in making decisions about its affairs, typically by voting to elect representatives to a parliament or similar assembly,” (a:) “government by the people; especially: rule of the majority” (b:) “a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodically held free elections.”

-Oxford English Dictionary

I hate democracy. And I hate organizations, especially communes. Yet, I favor the organization of democratic communes.

The author with HDP representatives at a Kobanê Day rally in Paris.

This

Democracy is always about mediation. Whether it separates the subject from decision-making, separates the subject from herself, or functions as an excuse for graft and fraud. Democracy stands in the way of the individual, blocks unmediated communication by imposing the requirement of structure—an outcome, a decision. And when a decision is reached, it is usually arrived at by the most banal and ruthless method ever devised: the vote—the tyranny of the majority.

Anarchism has had a mixed history of criticism regarding democracy. Étienne de La Boétie in his Discours lays out a first line of inquiry by wondering why it is that people allow themselves to be governed at all—and as he explores the problem, he points out that it seems not to matter whether a tyrant is chosen by force of arms, by inheritance, or by the vote. “For although the means of coming into power differ, still the method of ruling is practically the same; those who are elected act as if they were breaking in bullocks; those who are conquerors make the people their prey; those who are heirs plan to treat them as if they were their natural slaves.” (1) And it might be added that the subject population submits to such abuse without question and little contestation. La Boétie’s treatise is truly prescient; written in (roughly) 1553—a full 250 years before the emergence of the modern nation-state—it contemplates exactly the type of unbridled war, oppression, and terror that democratically elected governments were to unleash on subject populations, and each other.

Power cannot exist in stasis; it functions as a result of flows between and among institutions and individuals. The monarchs of Europe learned this lesson the hard way during the upheavals of 1848 as they watched their respective regimes disintegrate one after the other. With democracy came the calculation of exchange—one iota of power given to a citizen via the vote—concentrating a vast quantity of power in legislature, executive, and judiciary. It’s unsurprising that political systems began to apply equations of power and exchange at the same time that in the economic realm Capital was introducing similar equations in order to usurp labor-time in trade for survival. Further, such an exchange ties the population all that much closer to the rulers. Vaneigem illustrates the mechanism thus: “Slaves are not willing slaves for long if they are not compensated for their submission by a shred of power: all subjection entails the right to a measure of power, and there is no such thing as power that does not embody a degree of submission.” (2)

It was Proudhon who had the most varied interaction with democracy, both theoretically and practically. His career included writing and publishing tomes of critical analysis denouncing democracy, running for elected office, serving in the National Assembly during the 1848 Revolution, and finally returning to his original rejection of voting and representation. He alternately urged his readers to abstain from voting, then to vote, then to abstain from voting (again), and finally to cast blank ballots to protest voting.

Proudhon unleashed a number of critiques on democracy. The critical prisms he used vary from the purely psychological to the empirical, and the targets of his barbs span the entire menagerie of democratic platitudes from sovereignty to the myth of “The People” to the realpolitik of how legislatures operate. Of interest is his critical analysis of the democratic decision-making process itself. He scrutinizes the mechanism of the vote and its outcome, specifically majority rule: “Democracy is nothing but the tyranny of majorities, the most execrable tyranny of all, for it is not based on the authority of a religion, nor on a nobility of blood, nor on the prerogatives of fortune: it has number as its base, and for a mask the name of the People.” (3)

But Proudhon doesn’t finish there. He protests that those left in the minority are forced by circumstance to follow the will of the majority—a situation he finds untenable, not only for the explicit coercion, but also because those in the minority are forced to abjure their ideas and beliefs in favor of those who oppose them. This, he notes wryly, makes sense only when political views are so loosely held by individuals so as to hardly be worthy of the name. Analyzing the same scenario, William Godwin declares, “nothing can more directly contribute to the deprivation of the human understanding and character” than to require people to act contrary to their own reason. A conclusion proven empirically when one conducts even the most rudimentary survey of representative government and its effects on humanity over the course of the past 250 years.

In conclusion: for an anarchist, for myself, democracy—as a system of self-governance, as a decision-making tool, as an ideal—is utterly devoid of redeeming value. It functions as a mask for coercion, making horror palatable while producing unbearable consequences for the individual, for the species, and for the planet. A dead end.

Border crossing on the Tigris River into the Kurdish Autonomous region.

That

It is at this point that most anarchists and critical theorists begin backpedaling, some slowly (like Proudhon) and others rapidly (like Bookchin). Historically, theorists have offered a scathing critique of democracy and then immediately digressed, stating that the representative form of democracy as conceived by bourgeois (or socialist) society isn’t really democracy. That real democracy is reflected in some other form—for Proudhon, delegated democracy, for Bookchin, the Greek city-states or the Helvetican Confederation. The argument then becomes that democracy can (and should) be recuperated (4) by the Left as a workable form.

My own critique veers wildly off course at this point, having been skewed by empirical observation of an alternate form of democratic practice. I’ve recently returned from the Kurdish Autonomous Region in Northern Syria, known as Rojava, where I had the opportunity to observe a unique form of democracy implemented by a revolutionary libertarian social movement.

Some theoretical context: in 1999, Abdullah Öcalan, the head of the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK, the Kurdistan Worker’s Party) was captured by Turkish Security Forces, with assistance from the CIA and Israel’s Mossad. Dodging a firing squad, he was eventually sentenced to aggravated life imprisonment—and that’s where things get interesting. Rather than making license plates or working in the laundry, Öcalan began the long slow intellectual journey out of Marxist-Leninist gibberish into some pretty durable anarchist theory. He eventually published his ideas in several works including Democratic Confederalism, War and Peace in Kurdistan, and a multi-volume tome on civilization, particularly the Middle East and Abrahamic religions. In his writing, Öcalan does what no one in the contemporary North American anarchist milieu is even willing to think—he constructs, albeit vaguely, a blueprint for a libertarian society. This simple exercise, content aside, is incredible. His engagement resembles far more the utopian socialist project of the early 19th Century than any of the ensuing theoretics associated with social contestation, especially Marxism and working class anarchism; indeed, his silence on class analysis, Marxist teleology, historical materialism, and syndicalism is deafening. Öcalan is clear in his task when he states, in “The Principles of Democratic Confederalism,” that “Democratic confederalism is a non-state social paradigm. It is not controlled by a state. At the same time, democratic confederalism is the cultural organizational blueprint of a democratic nation. ” [emphasis mine] (5)

As implied in the name, there is a great reliance on democratic processes in the system known as Democratic Confederalism. Yet Öcalan is silent about the definition of democracy—he never offers one—and it’s implementation: he never discusses it with any specificity. In fact, democracy is presented as a given, as a decision-making process, as an approach to self-administration, and little else. There is no favoring of voting versus consensus-based models, nor does he describe in any detail or at any level (communal, cantonal, regional) the forms that he foresees democracy taking. For example, “[Democratic Confederalism] can be called a non-state political administration or a democracy without a state. Democratic decision-making processes must not be confused with the processes known from public administration. States only administrate [sic] while democracies govern. States are founded on power; democracies are based on collective consensus.” He expands on what he means by “decision-making processes” in “The Principles of Democratic Confederalism”: “Democratic Confederalism is based on grass-roots participation. Its decision-making processes lie with the communities.” Fair enough. So how does all this play out in Rojava? In other words, how are Öcalan’s ideas being translated into revolutionary institutions?

I gained my first insight into democracy in Rojava over a plate of hummus and pita in downtown Kobanî. I was sitting with Mr. Shaiko, a TEV-DEM (Tevgera Civaka Demokratîk, Movement for a Democratic Society) representative on a warm, dusty afternoon, some three days after we had attended a commune meeting together. In that meeting, of the council of Şehid Kawa C commune, Mr. Shaiko had raised the issue of commune boundaries and perhaps moving them to account for the number of people returning to the rubbled, venerable hulk that is Kobanî. After some discussion, Mr. Shaiko left the meeting, requesting a phone call to let him know what they decided.

“So,” I asked Mr. Shaiko, “What happened with the commune? Did they call?”

“No, no decision yet.”

“Oh, do they need to give one?”

“No, they’ll decide when they’re ready. That’s how it is,” Mr. Shaiko looked at me over his glasses with a half-grin and then returned to the plate of pita and hummus.

This is clearly a divergent view of democratic decision-making, in which no conclusive result is as valid a response as a “yes” or a “no.” While I only saw this adjustment to democratic decision-making in operation a few times it seems to be fairly common, especially with the TEV-DEM folks whose charge is implementing democratic confederalism. It is also an interesting “fix” applied to the issue of decision-making processes. In a sense, it negates the democratic process in favor of discourse, argument, and engagement, without the concomitant requirement of an outcome.

The response of the revolutionaries to the tyranny of majority rule has been structural rather than directive. Here, Öcalan describes his views on a plural society and outlines how he plans to weaken or subsume majority rule: “In contrast to a centralist and bureaucratic understanding of administration and exercise of power confederalism poses a type of political self-administration where all groups of the society and all cultural identities can express themselves in local meetings, general conventions and councils… We do not need big theories here, what we need is the will to lend expression to… social needs by strengthening the autonomy of the social actors structurally and by creating the conditions for the organization of the society as a whole. The creation of an operational level where all kinds of social and political groups, religious communities, or intellectual tendencies can express themselves directly in all local decision-making processes can also be called participative democracy.”

So for the revolutionaries the formation, growth and proliferation of all types of “social actors”—communes, councils, consultative bodies, organizations and even militias—is to be welcomed, and encouraged.

This plays out in Rojava in a patchwork quilt of organizations, interests, local collectives, religious affiliates, and… flags. For example, TEV-DEM, the umbrella organization charged with implementing democratic self-administration, is actually an agglomeration of several smaller organizations and representatives from political parties. These various organizations include groups centering around sport, culture, religion, women’s issues, and more. For example, in December of 2015, a new organization under the TEV-DEM system was born—TEV-ÇAND Jihn, which focuses on women and cultural production. This new organization is in addition to the generic TEV-ÇAND, which focuses on society, generally, and cultural production. To sidestep the problems with majority rule, the revolutionaries have introduced a structural caveat that allows individuals to find an organization that suits their needs, and through which their voice can be heard in society. Note that TEV-DEM and others have not sought to tinker with the actual mechanics of how a commune or organization operates or decides. Rather, they have changed the social order such that if an individual refuses to uphold a decision by a group, commune or council, she always has the ability to opt out and find a more amenable assembly.

These innovations seem like good first steps towards turning democracy from a worthless antiquity into a workable principle within anarchist theory. As such, they should be encouraged and studied.

Meeting of Commune Şehîd Kawa C council to determine possible new boundaries. Mr. Shaiko, TEV-DEM representative points to map of Şehîd Kawa neighborhood.

Martyr poster on the road from Qamishlo to Kobanê. Note picture of Abdullah Öcalan at the top.

This

My essay regarding the organizational form and its various moments of domination, “The Organization’s New Clothes,” was first published in February of 1989 (and republished in 2015), and I see no reason to retract any portion thereof. (6) That critique, therefore, resonates throughout the following discussion, though time and space prohibit using it in any way other than as a critical prism.

The commune is a scrambled term. Its origins lie in the smallest administrative entity in France, the commune—corresponding roughly to a municipality. The word itself is derived from the twelfth-century Medieval Latin communia, meaning a group of people living a common or shared life. This is an interesting point of departure in that, even then, the concept implied some degree of autonomy, both political and economic. It was, however, the Paris Commune during the French Revolution (1789-1795) that wrote the term in large red letters in the book of revolution. In that first great explosion, the Communards distinguished themselves by their intransigence and demands for the abolition of private property and social classes, eventually earning themselves the nickname les enrages (“the enraged ones”).

The revolutionary commune, then, has a subversive nature. It is dangerous. It is always dangerous when humans interact beyond the terrain of Capital and state, or in opposition to them.

Throughout the 19th century, outside the administrative network of France, the term commune came to be associated with socialist and communist experiments and, in a looser sense, with all manner of utopian projects and communities—Owen, Fourier, Oneida, Amana, Modern Times. There was a slump for a few decades through the first part of the 20th century, and then, to confuse things further, the 1960s happened. The definition of the word “commune” ends for many North Americans somewhere in 1972, in a tangerine swirl of bad acid, free love, and the Manson Family.

Which is not to say that there weren’t some important projects. Among the more interesting were the West Berlin-based Kommune 1(1967-1969) and Wisconsin’s contribution to utopia, Dreamtime Village. There have been thousands (likely tens of thousands) of communes over the past two centuries: intentional communities, collectives, cooperatives, each with its own “glue”—the stuff that brought people together and “stuck” them to one another. In most cases, this glue has been a mix of politics, anarchism, communism, utopianism, religious sentiment (usually wacky), livelihood, necessity, drugs, sexuality, or just plain detesting the dominant culture.

So what, exactly, is a commune? Who the hell knows? The problem is not the vagueness with which the commune is understood; rather, it’s the lack of theory (and experience) that would provide nuance to this vagueness. The idea of the commune has been lost or diluted as a result of its own jangled historical context and the easily recuperable forms that it has recently taken. Ultimately, very much like democracy, the commune seems a quaint and faded relic in the cabinet of anarchist theory, filed under “V” for vestigial.

A village near Qamishlo; the majority of Rojava’s residents live in such settlements.

That

As above, so below. My own relation with the Commune spans several articles on the Paris events of 1871, and includes my ongoing engagement with the conundrum of anarchist organization. All of my interactions with the concept of organizations operating in a revolutionary context had been on paper—in theory—until I crossed into the Kurdish Autonomous Region. Then things changed.

The commune and council meetings I attended varied widely, ranging from an ad hoc encounter of a team of YPG militiamen near the Turkish border in Kobanî Canton to a council of the Şehid Kawa C commune, to a ceremony and meeting between TEV-DEM representatives of Kobanî and Cizîrê Canton. In each instance, I recall a series of similar impressions. First, each encounter was characterized by a sense of purpose, of meaning. The attendees seemed clear that what they were engaged in, the simple task of meeting together—as a commune, as a team of YPG fighters—carried within it a seed, a possible future, for Northern Syria, perhaps for the planet. Many people commented on this when I asked their thoughts regarding these political forms. A woman I met in Paris at an HDP rally put it best: “We are here reinventing politics, in fact, the world.”

This perception, which could easily foster arrogance, seemed instead to produce a mindset of quiet determination in these attendees. These folks were not wealthy, they worked hard in an area where there was little work. The men’s faces were lined and etched with long hours spent under the harsh Middle East sun. The hands of the women were simultaneously delicate and rough: while they bore callouses and cuts, they also carried the scent of lotion and perfume. The voices, gestures, and faces of the revolutionaries during the meetings were intent, searching, serious. There was kindness, hugs for a developmentally disabled young adult, a moment spent with a mother who had lost a son in the siege of Kobanî, and respect—as each person spoke to the accompaniment of silent nods from their peers.

There was also hope, a quantity that history has so long denied to anarchists, and which some of us have reclaimed—not as an eventuality, but as a birthright. These folks believed that they could change their lives, their community; many believed they could change (and were changing) the world.

Finally, and most importantly, in each of these meetings there was an overwhelming sense of the ordinary. When they mentioned the cantonal authority at all, these folks referred to it laconically as the anti-government, or the anti-regime. They had seen and participated in sweeping social changes and experimentation, and in the process it had become commonplace, like lunch. This is not to say that there was no joy in the proceedings, far from it. Rather, what was really missing was fear, and in this sense the social revolution in Rojava may truly be said to have passed into a phase of maturity and permanence. The sole condition in the short-term being the defeat of Daesh.

Some theorists have been advancing on the idea of the commune, but from strange directions, post-left directions. Peter Lamborn Wilson in The Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ) and Pirate Utopias forces the issues of time and failure/success in reference to the commune. He rejects utterly, as we must, the technological reasoning that the longer a commune exists the better or more successful it must be. In TAZ, he specifically provides a formula for a new idea of a commune, a temporary encounter—perhaps hours, perhaps minutes—characterized by conviviality, joy. This encounter is autonomous in that it is as independent and free of the fetters of Capital and state as possible. This is essential to understand. The commune is combative, not subservient. That is the basis of its autonomy.

Rather than bounding the definition of the commune or trying to refine it, I believe that defocusing the concept seems a sound strategy. I would argue that whether it is a phalanstère with all the Fourierist fauna intact, or a meeting between friends to relive old times or create new ones, it doesn’t matter—it is a commune. Why bound something, why hem something in when it presents itself as a viable model for organization? Rather, without a definition, we can move with tiny baby steps towards an understanding of what works and what is useless in the commune model. That strikes me as one promising, potential direction towards both engaged social experimentation and ruthless social contestation.

Finally, at a macro-level, the concept of federalism may make a theoretical comeback. If the commune model makes any sense at all, then federalism isn’t very far behind. This returns anarchism to its philosophical roots—Proudhon especially, but also Pi i Margall and Bakunin. The insurrectionary potential for federalism seems vastly underestimated. The movement to divide society into smaller and smaller units, the federation of these units by mutual agreement, and the potential for economic cooperation and shared self-defense make federalism a potentially daunting, though rather blunt, instrument. Note here that the current usage of federalism—the nation-state’s accumulation of power, wealth, and knowledge in order to control and dominate subject populations—is precisely the opposite of the concept’s standard historical definition. It is Pi i Margall, the non-anarchist grandfather of Spanish anarchism, in his 1855 work La Reacción y la Revolución, who offers the final word on the potential of federalism: “The constitution of a society without power is the ultimate of my revolutionary aspirations,” stating he would, “divide and subdivide power,” in order to “destroy it.” (7)

The formation of communes also seems a viable real world strategy in that it fulfills two immediate functions. First, they can act as support, a backbone for the movement of militants quickly to areas where their services might be required. In this way, they may function very much as the bookstores, infoshops, and alternative spaces did in the anarchist milieu of the past several decades in the US, or as the communes did in Kobanî during the siege. Their resources can assist in the provision of shelter, food, medical aid, and comfort for fighters. The communes can also provide valuable intelligence on local conditions, law enforcement, and assist in identifying those specific targets most noxious to the community. Put in contemporary military parlance, one type of commune may not be a weapon, but it can function as a weapons platform for the mobile anarchist fighters.

Secondly, the communes provide for the sedentary members of the milieu a laboratory, a setting in which to experiment with new ideas, new forms, coalescing, in protoplasmic form, the seeds of revolutionary institutions yet to be. Communes are nurseries where budding insurrections are reared. Ancillary to this effect, yet no less important, is the possibility that communes will help to offset the attrition that has plagued anarchism since its inception as a political movement. A life dedicated to liberty is difficult to sustain, and most anarchists [who can] eventually succumb to the Cthulhu call of new cars, big houses, and squandered lives. At the age of 55, I have seen thousands of anarchists come and go; only those too stubborn or anti-social, like my friends and myself, seem to remain. Communes may stem this drift by producing a social milieu that is amenable to the various vagaries of the anarchist personality type, and by distributing resources for assistance with the real world issues of food, shelter, childbirth and rearing, loneliness, illness, old age and death.

The commune is a verb. The commune is a question.

An exploded mine on the road between Serekaniye and Kobanê.

The Other Thing

Anarchism has been adrift since the end of the Second World War. With little understanding of its roots, history, and struggles, most of us did the best we could with what we could find. There were no organizations to criticize or join; it was difficult enough just to find anarchists in NYC in 1984. We were orphans. The situation has changed: there are more anarchists, they are more easily contacted and the explosion of information has given us our story back. As a confluence, the news out of Greece, Rojava, Europe, in fact just about everywhere seems to be turning in our direction. Those in the milieu, therefore, have some choices to make about where to place energy, where to invest time and effort, in a word—what to do? There are at least as many possible answers to this question as there are anarchists now alive. As my response, I suggest the following:

Form democratic communes.

Federate.

Be ready.

Destroyed tanks and little girl, near YPG/J headquarters in Kobanê.

References

La Boetie, Etienne (1975) The Politics of Obedience: The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude. Montreal; Black Rose Books.

Vaneigem, Raoul. (1994) The Revolution of Everyday Life (Donald Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). London: Rebel Press.

Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. (1867-1870) Oeuvres completes de P-J. Proudhon. Paris: A. Lacroix, Verboeckhoven et Cie.

Recuperation is a concept developed by the Situationists to describe the process in which ideas and strategies that originally served a revolutionary agenda, are appropriated by Capital and the state to preserve the status quo.

Ocalan, Abdullah (2011). Democratic Confederalism (transl. International Initiative). Transmedia Publishing Ltd. London, Cologne

Simons, Paul Z. (2015). “The Organization’s New Clothes,” Black Eye: Pathogenic and Perverse. Ardent Press, Berkeley CA.

Pi y Margall, Francisco. “Reaction and Revolution,” in Anarchism, A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas Volume One

May 18, 2016

Confronting Cops and Klan in Stone Mountain

On April 23, 2016, hundreds of people gathered to oppose a rally called by the Ku Klux Klan at Stone Mountain Park, Georgia. This convergence brought together a wide range of groups committed to shutting down the KKK. The crowd circumvented several blockades consisting of hundreds of local officers, riot police, and state SWAT teams to reach the parking lot where the white supremacists were assembling.

This was just one of many events in the wave of black-led revolt since the eruption in Ferguson, Missouri in August 2014 following the murder of Mike Brown. To understand the context of what happened in Stone Mountain, we have to pan back across the struggles of the preceding years. In this report, we recount the demonstrations that led up to this one and offer a blow-by-blow account of the action for everyone who may have to mobilize in response to similar rallies in the years to come.

Background: Against Police and White Supremacy in Atlanta, 2011-2015

August 2011: Troy Davis

In fall 2011, Troy Anthony Davis was executed by the State of Georgia for allegedly killing a police officer in 1989. In the week preceding his execution, thousands of people took the streets of Atlanta and the parking lot outside of Jackson Prison, where the execution was to take place. While Amnesty International and other non-profit organizations held protests during the day, autonomous groups coordinated multiple breakaway marches and an overnight occupation of the plaza of the GA Board of Pardon and Paroles. This was one of the first signs of confrontational protest Atlanta had seen in years.

September-December 2011: Occupy Atlanta

While the Occupy movement was camped out downtown, metro Atlanta police killed many black people and at least one white person. When an officer murdered Joetavius Stafford on his way home from prom, Occupy protesters and others marched through downtown, flooding a train station and chanting anti-police slogans. When Dwight Person was shot to death in his East Point living room, angry Occupy protesters, recently evicted by riot police, marched through downtown again. When Ariston Waiters was shot in the back while handcuffed in Union City, a predominantly white black bloc joined black youth in painting graffiti and smashing the windows of the Justice Center.

March 2012: Trayvon Martin

After George Zimmerman murdered Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, thousands of people rallied at the state capitol. Mostly black university students and churches led chants and prayers for several hours, casting dubious glances at the predominantly white masked demonstrators who later joined others in a breakaway march of perhaps 100. The march vandalized nearly a dozen police cruisers, stomping in windshields and smashing windows with no arrests. No news station reported the vandalism.

August 2012: Troy Davis Anniversary

On the one-year anniversary of the execution of Troy Davis, around 100 demonstrators marched through downtown chanting anti-police slogans.

July 2013: Zimmerman Verdict

Immediately after the verdict of “not guilty” in the Zimmerman trial, a crowd marched downtown. Masked demonstrators and unmasked young black participants began vandalizing construction equipment and painting graffiti. Other black and white activists physically obstructed this behavior. The next day, thousands marched with the Trayvon Martin Organizing Committee from West End to downtown via a highway. Black professionals, activists, and clergy physically assaulted white people in the masked contingent and collaborated with police to attempt to isolate them. Later, masked protesters made a poorly timed attack on a police cruiser. No one was arrested.

April 2013: Edgewood Courts

On April 8, 2013, Atlanta police pepper-sprayed and beat a crowd of children and their parents playing kickball in the Edgewood Courts Apartments in northeast Atlanta. The following day, over 100 residents joined by others spontaneously marched and attacked police with bricks and bottles for an hour. No one pleaded for nonviolence or argued against masking.

Protesters block a highway in Atlanta on October 22, 2014.

Fall-Winter 2014: Ferguson Solidarity

Following the explosion of anti-police revolt in Ferguson, Missouri, demonstrations spread to hundreds of cities around the US. Dozens of protests took place in the Atlanta area under the Black Lives Matter banner. Activists hoping to impose nonviolence and top-down control repeatedly failed to outmaneuver anarchists and other participants intent on being uncontrollable. From August to November, several marches blocked traffic and one demonstration forced police out of West End. These crowds were racially diverse, comprised largely of students, young workers, artists, skateboarders, and professionals from non-profit organizations.

November 25, 2014: Non-indictment of Darren Wilson

Following the failure to indict Darren Wilson in the murder of Michael Brown, thousands of people took to the streets near Underground Atlanta, a predominantly poor and black shopping area downtown. The night before, organizers from a few different activist organizations had met secretly with police to develop a plan to avoid the mass conflict that had engulfed St. Louis, Oakland, Seattle, and other cities. Despite this, two hours into the protest, a breakaway group of masked people with a sound system joined by nearly 1,000 people marched into downtown toward the capitol building. They began overturning barricades and trash cans while lighting traffic flares, engaged in a shoving match with Capitol police armed with machine guns, and then marched onto the I-75/85 highway connector, blocking traffic and throwing stones at police. A smaller but determined group of roughly 100 including gang members, black and white proletarians, anarchists, and other autonomous groups threw projectiles at police for nearly an hour before being joined by others at Underground Atlanta. The now much larger crowd was strictly divided about street conflict, with white and black students and activists marching in the back, booing and filming, while multiracial groups towards the front clashed with police and vandalized storefronts on Peachtree Street. Eventually, riot police dispersed the crowd and arrested dozens. Afterwards, some activist groups popularized the theory that “white anarchists” had caused the repression. A group called the Atlanta-Ferguson Solidarity Committee released a statement to the news decrying the arrests and the peace police who attempted to “citizen’s-arrest” a vandal.

March in Atlanta on November 25, 2014.

Winter 2015: Eric Garner, Nicholas Thomas, Anthony Hill