CrimethInc.'s Blog, page 3

April 26, 2016

#48: From Democracy to Freedom Audio Zine

#48: From Democracy to Freedom Audio Zine — Welcome back to the Ex-worker! We’re eschewing our typical format once again to bring you our second audio zine, a production of Crimethinc.’s new text From Democracy to Freedom. This release coincides with the announcement of an online platform for participating in decentralized reading groups and online discussions on this text as well as the others in the series exploring questions around democracy, and how we relate to it as anarchists.

You can download this and all of our previous episodes online. You can also subscribe in iTunes here or just add the feed URL to your podcast player of choice. Rate us on iTunes and let us know what you think, or send us an email to podcast@crimethinc.com. You can also call us 24 hours a day at 202–59-NOWRK, that is, 202–596–6975.

April 19, 2016

Anarchy and Democracy Reading Groups!

This month, we are publishing a series exploring an anarchist analysis of democracy, including case studies from anarchist participants in directly democratic movements around the world. As an offline counterpart to the series, we invite you to organize discussion groups about the relation between democracy and anarchy. We’re not finished thinking through this topic, and we want your help engaging with these questions. Our hope is that together we can produce new ideas and tactics that can be put to use in the next wave of unrest.

To facilitate all this, we’ve prepared print-ready PDF of the flagship text in the series, “From Democracy to Freedom”:

From Democracy to Freedom imposed PDF [6.5mb]

To complement what we hope will be a network of such discussion groups, we’ve established a participatory forum utilizing our comrades’ platform Crabgrass, here:

we.riseup.net/democracyandanarchy

Here’s how to use the forums:

Visit we.riseup.net and make yourself a user profile.

Click on the “Settings” tab and configure your profile to match your needs.

Click on the “Groups” tab at the top left of the page (next to the raven icon).

From the “Groups” tab, select “Search” from your options on the left. Type “democracyandanarchy” into the search box and click “Search.”

Join the “democracyandanarchy” forum by clicking on it and then clicking “Join Organization” on the left. This enables you to read and contribute to discussion threads.

Commence critiquing the articles, posing and answering hard questions, summarizing the discussions you’ve had offline, and more!

Ideally, we’d like people to meet in person to discuss the texts, even in groups as small as two, and to use the online forum to compare your thoughts with other groups and pose each other questions. If you lack offline community, or want to share the discussion from your local group, we hope the forum can connect you with others who share your interests. The Ex-Worker podcast will draw material from the discussions on the forum to include in future episodes of the podcast.

You can draw from and add to a list of discussion questions for reading groups at the forum site. If you have technical questions about using Crabgrass or other Riseup services, try the Crabgrass Help Pages. You can also email us at rollingthunder@crimethinc.com.

Discussion Questions for Reading Groups

Here are some of the discussion questions that reading groups and individual readers have proposed. Please add your own!

—Which arguments don’t you find convincing in the texts? Make counterarguments!

—What examples from your local experience illustrate the difference between anarchistic and democratic models for decision-making and action?

—How can we use the word “democracy” to inform our conversations around our use of language?

—In what ways are your personal relationships democratic? In what ways are they anarchistic?

—Does this text (or series) offer anything new or of interest when it comes to how to live? Does it suggest ideas for new ways of living, within the world as it is and in a future world?

—In a society that has championed democratic principles as the sacrosanct foundation of freedom itself, it can be very difficult to make a case for anarchistic organizing. Can you think of any examples of people making anarchistic values more comprehensible and convincing than democratic principles?

—Is there more than one stateless alternative to democracy? Can you identify multiple irreconcilable stateless alternatives to it?

—Arguably, democracy has spread around the world because it is an effective means of binding people together in formations that concentrate power, regardless of whether this is in the best interests of any the individual participants. Following Foucault, we can say that democracy is not just oppressive, it is productive. We can critique democracy on purely ethical grounds, but this does not equip us to supersede it or to defend ourselves against democratic states or projects. Are there examples of decentralized and autonomous networks that have been more efficient or more powerful than democratic institutions?

—In what ways do the new social relations we see emerging in the age of social media already fulfill the demand for direct democracy that is just now appearing in the political sphere? In what ways are these relations already post-democratic? Insofar as they are post-democratic, are they all we would want from an alternative to democracy, or are they repressive or exclusive in other ways?

—David Graeber’s “There Never Was a West” is one of the most compelling articulations of how an anarchist might embrace the language of democracy. Compare and contrast it with the arguments and historiography of the texts in the CrimethInc. series.

April 15, 2016

Steal Something from Work Day 2016

Today we take a break from our ongoing series about the anarchist critique of democracy to observe an annual day of action, Steal Something from Work Day.

Today is April 15—in the US, the day that taxes are usually due to the federal government. Ironically, this time tax day has been moved back to Monday so the IRS can celebrate Emancipation Day—which the rest of us have no opportunity to celebrate, chained as we are to the grindstone. Slavery has been abolished, but wage slavery persists.

The government steals a part of our labor in the form of taxes. Our employers steal a part of our labor in the form of profit. And the necessity of working steals our lives, one day after another—it steals us from each other, forcing us to toil to keep the bills paid rather than being creative together or spending time with our children.

We can build towards a worldwide movement to abolish the imposed scarcities and controls that force this situation on us. But in the meantime, we have to be pragmatic, to do the best we can with the opportunities available to us. That’s why people all around the world celebrate April 15 as Steal Something from Work Day.

Don’t Beg for Crumbs—Take the Whole Pizza for Yourself!

Being from the part of the world that is considered Eastern Europe in the West, you get paid a lot less for the same shitty jobs. I had a few of those jobs already, starting at the age of 14, usually sorting products on the shelves in the big hypermarkets. The theft prevention there seemed omnipotent, so however angry I was about getting paid the equivalent of $1.50 an hour (25% of which was taken by the contractor agency through which I found work), I had no idea how to do anything to improve my situation.

One day, I told myself I couldn’t carry like that for the rest of my life. I would rather risk and even lose my job than never try, and instead lose myself. By then, I worked behind the counter at a KFC franchise; my salary was still less than $2 an hour. This was a decade ago, and I doubt much has changed since then.

As a 16-year-old punk, before I even made a single crown, I had to buy my own fancy shoes to go with the ugly uniform, which had false pockets so the employees couldn’t steal. Although I already considered KFC to be an icon of pure evil, I never ceased to be surprised by the politics and regulations for workers. I couldn’t keep tips—they wouldn’t feed us for free—the leftovers were thrown into the trash, which was kept locked in a special room.

My first idea was to invite couple of friends for lunch and give them a lot of food for free when the manager wasn’t looking, then try to take a lunch break so I could eat some of the food too. Eventually, I realized that if I went for supplies to the refrigeration room, I could eat there—but it was so cold, and anyone could open the door at any time. I started to see more and more employees eating in the kitchen, smuggling food to the bathroom and locking themselves there, or sneaking it behind the counter when the manager went out to smoke.

I started to build up to talking about it with the other workers; until then, it had been taboo to talk about getting back what we deserved. People got more conscious and started to help each other to get as much food as possible for lunch, like preparing a big bucket of food in the kitchen and then taking the manager out for a cigarette break so the one going for lunch could take it upstairs. From the counter, we would bring soda, coffee, muffins, and such back to the workers who had no access to those things.

I was new to working and still went to high school, so I didn’t work that often. I wanted to get some food and leftovers to bring home and to school, to share with my family and friends. We made a deal that my colleagues would make a bag of food for me and leave it in the back so I could grab it when I went to change while the manager counted out my cash register.

It was nice to be able to eat for free and share with the others. But soon, everyone got tired of eating ultra-spicy steroid-filled fried chicken wings with fries and mayonnaise. I became vegetarian, and soon vegan. I felt like stealing food didn’t really pay me back for all the time I spent there in constant hustle and stress, sometimes without any breaks. Free wings didn’t pay for all the cigarettes I started to smoke when I worked there. It just wasn’t enough.

Thinking about it every day and getting more committed to breaking the rules, I figured out that no one was watching the security cameras and they didn’t archive the records. I discovered that I could open my register by typing that I sold a small drink, fries, or even a helping of ketchup. I quickly learned how to keep track of the costs of different items; if a customer had money ready or was in a hurry, I would first make the whole order and count it in my mind, then take the money, typing that I had sold something much cheaper. By doing that several times a day, I physically kept much more money in the register than they expected according the system.

Yes, this is simple and they knew about it—that’s why we didn’t have any pockets and they would check to make sure that we weren’t leaving with money in our hands or elsewhere. To bypass this control, I would ask some of my friends to come in for food, pretend we didn’t know each other, and pay with big bills. This time, I would type everything beforehand and correctly, in order not to be suspicious if the manager came around; but when giving the change back, I would give them all the money I knew I had saved during the day. In this way I would split the money with some friends who also had financial problems.

Once, my manager told me I had to clean the tables in the lobby for the rest of the day as soon as I finished with my next customer. At that point, I had way more money in my register than I was supposed to, so I pretended to tie my shoelace and put some money into my sock. I was still over the expected amount in the register, but I explained that I got big tips that day. It was good to know that I could get the money out myself so I could steal a bit every day rather than a big amount once in a while when my friends came. After that, I started to make pretty good money for a teenager.

All the same, working there became unbearable. The end of last shift felt so liberating. I couldn’t believe they didn’t catch me.

I started to work at a pizza window. Once again, we were not paid well. But in this new workplace, to my surprise, the workers had a system by which to multiply their income. In addition to selling weed alongside pizza, they figured out that the owner only kept up with the stock by counting the balls of dough. He was a busy man, opening more and more places; he never did any work besides coming in to take the cash at night. He always had a new car or fancy stuff. We sold big pizzas by pieces, so he wasn’t counting boxes, just the dough that we had to press into the pizza bases. My colleagues figured out that they could make seven pizzas out of the dough intended for six by setting a bit of each dough ball aside. Soon we were making four pizzas out of three balls, so our crew could sell every fourth pizza for the direct profit of the workers, and split 25% of the daily gross among ourselves.

Sometimes the boss would say we were using too much cheese or tomato sauce. Then we would buy our own supplies to make the extra pizzas, and still come out ahead. It was a workers’ cooperative pizza shop within a capitalist pizza shop.

Nowadays, looking back, I remember those times as less risky than my adult life has been, in which (like many people in this country) in order to survive I have to be officially unemployed while I make a living under the table, supplemented by shoplifting and insurance frauds. It’s too bad the customers had to eat those thin little pizzas, but hey, I’m not the one who came up with this social order or the incentives that drive it! If you want thick crust pizza, abolish capitalism!

Steal Something from Work Day Resources

A Theft or Work?—A grad student brings poststructuralist theory to bear on time theft, why the master’s degrees will never dismantle the master’s house, and how to resist work when it has spread so far beyond the workplace

Out Of Stock: Confessions Of A Grocery Store Guerrilla—A former Whole Foods employee recounts his efforts to run his employer out of business by means of sabotage, graffiti, and insubordination, reinterpreting William Butler Yeats’ line “The falcon cannot hear the falconer” from a bird’s-eye view.

Steal from Work to Create Autonomous Zones—The shocking true story of how a photocopy scam nearly escalated into global revolution.

What Became of the Boxes—An adventure in proletarian revenge.

And there’s more! Steal Something from Work Day videos, corporate media coverage, and even a journal (pdf, 4.3 MB).

April 14, 2016

Occupy: Democracy versus Autonomy

The story goes that the very first gathering of Occupy Wall Street began as an old-fashioned top-down rally with speakers droning on—until a Greek student (and perhaps—an anarchist?) interrupted it and demanded that they hold a proper horizontal assembly instead. She and some of the youngsters in attendance sat down in a circle on the other side of the plaza and began holding a meeting using consensus process. One by one, people trickled over from the audience that had been listening to speakers and joined the circle. It was August 2, 2011.

Here, in the origin myth of the Occupy Movement, we encounter a fundamental ambiguity in its relationship to organization. We can understand this shift to consensus process as the adoption of a more inclusive and therefore more legitimate democratic model, anticipating later claims that the general assemblies of Occupy represented real democracy in action. Or we can focus on the decision to withdraw from the initial rally, seeing it as a gesture in favor of voluntary association. Over the following year, this internal tension erupted repeatedly, pitting democrats determined to demonstrate a new form of governance against anarchists intent upon asserting the primacy of autonomy.

Though David Graeber encouraged participants to regard consensus as a set of principles rather than rules, both proponents and authoritarian opponents of consensus process persisted in treating it as a formal means of government—while anarchists who shared Graeber’s framework found themselves outside the consensus reality of their fellow Occupiers. The movement’s failure to reach consensus about the meaning of consensus itself culminated with ugly attacks in which Rebecca Solnit and Chris Hedges attempted to brand anarchist participants as violent thugs.

How did that play out in the hinterlands, where small-town Occupy groups took up the decision-making practices of Occupy Wall Street? The following narrative traces the tensions between democratic and autonomous organizational forms throughout the trajectory of one local occupation.

This text is an installment in our series exploring an anarchist analysis of democracy.

Democracy versus Autonomy in the Occupy Movement: A Narrative

A decade and a half ago, I participated in the so-called “anti-globalization movement,” so described by journalists who preferred not to say “anticapitalist.” Beginning with a groundswell of local initiatives, it culminated in a string of massive riots at international trade summits from Seattle in November 1999 to Genoa in July 2001. Although I had been an anarchist for some years already, I learned about consensus process in the course of those experiences. Like many other participants, I believed that this form of decision-making pointed the way to a world without government or capitalism. We cherished the seemingly impossible dream that one day that decision-making process might be taken up by the population at large.

Ten years later, I visited the Occupy Wall Street encampment at Zuccotti Park. It had only existed for two weeks, yet it had already developed its political culture: daily assemblies, “mic check,” consensus process. This was all familiar to me from my “anti-globalization” days, though most people there clearly did not share that background.

I heard a lot of legalistic and reformist rhetoric in the course of my brief visit. At the same time, this was what we had dreamed of, our practices spreading outside our milieu. Could the practices themselves instill the political values that had originally inspired us to employ them? Some of my comrades had argued that directly democratic models could be a radicalizing step towards anarchism. The following months put that theory to the test.

Two weeks after my visit to Manhattan, I was back in my hometown in Middle America, attending our Occupy group’s second assembly. A hundred people from a wide range of backgrounds and political perspectives were debating whether to establish an encampment. It’s not easy for a crowd arbitrarily convened through an open invitation on Facebook to make a decision together. Some argued against occupying, claiming that the police would evict us, insisting we should apply for a permit first. In the nearest city, occupiers had applied for a permit but were only granted one lasting a few hours; everyone who remained after it expired was arrested. A few of us thought it better to go forward without permission than to embolden the authorities to believe we would comply with whatever was convenient for them.

A different facilitator would have let the debate remain abstract indefinitely, effectively quashing the possibility of an occupation in the name of consensus. But ours cut right to the chase: “Raise your hand if you want to camp out here tonight.” A few hands went hesitantly up. “Looks like five… six, seven… OK, let’s split into two groups: those who want to occupy, and everyone else. We’ll reconvene in ten minutes.”

At first there were only a half dozen of us meeting on the occupiers’ side of the plaza, but after we took the first step, others drifted over. Ten minutes later, there were twenty-four of us—and that night dozens of people camped out in the Plaza. I stayed up all night waiting for the police to raid us, but they never showed up. We’d won the first round, expanding what everyone imagined to be possible—and we owed it to people taking the initiative autonomously, not to reaching consensus.

Our occupation was a success. Over the first few weeks, scores of new people met and got to know each other through demonstrations, logistical work, and nights of impassioned discussion.

The nightly assemblies served as a space to get to know each other politically. First, we heard a wide range of testimonials about why people were there. These ranged from boring to fascinating, but they died out swiftly once the business of making decisions via assemblies got underway. Next, we weathered lengthy debates about whether there should be a nonviolence policy, with nonviolence serving as a code word for legalistic obedience. Thanks to the participation of many anarchists, this discussion was split pretty much down the middle, but it enabled many occupiers who had never been part of something comparable to hear some new arguments.

It was interesting to watch so many people go through such a rapid political evolution. I enjoyed the debates, the drama of watching middle-class liberals struggle to converse on an equal footing with anarchists and other angry poor people.

On the other hand, the assemblies were ineffective as a way to make decisions. After weeks of grueling daily sessions, we gave up entirely on formulating a mission statement about our basic goals, consensus having been repeatedly blocked by a lone contrarian. Some people managed to push a couple small demonstrations through the consensus process, but they attracted almost no participants. The assembly’s stamp of approval did not correlate with people actually investing themselves; the momentum to make an effort succeed was determined elsewhere.

While the nightly assemblies helped us get to know each other politically, if you wanted to get to know people personally, you had to spend time at the encampment. Standing night watch, facing off with drunk college students and other reactionaries, I became acquainted with many of the occupiers who had first arrived as disconnected individuals. It was those connections that gave us cause to be invested in each other’s efforts over the following months.

Unexpectedly, the liberals were among the most invested in the protocol of consensus process—however unfamiliar it was, they found it reassuring that there was a proper way of doing things. This emphasis on protocol created rifts with the actual inhabitants of the encampment, many of whom felt ill at ease communicating in such a formal structure; that class divide proved to be a more fundamental conflict than any political disagreement. From the perspective of the liberals, there was a democratic assembly in which anyone could participate, and those who did not attend or speak up could not complain about the decisions made there. From the vantage point of the camp, the liberals showed up for an hour or two every couple days, and expected to be able to dictate decisions to people who were in the camp twenty-four hours a day—often not even sticking around to implement them.

As a part of the minority that was familiar with consensus process yet simultaneously a denizen of the camp proper, I could see both sides. I tried to explain to the liberals who just showed up for the assemblies—the ones who understood Occupy as a political project rather than a social space—that there were already functioning decision-making processes at work in the encampment, however informal, and if they wanted to establish better relations with the residents of the encampment, they should take those processes seriously and try to participate in them, too.

After the first few weeks, the flow of new participants slowed. We became a known quantity once more. Consequently, we began to lose our leverage on the authorities. Meanwhile, it was getting colder out, and winter was on the way. Based on our experience attempting to formulate a mission statement or call for demonstrations, it seemed clear to us that if there was to be a next step, it would have to be decided outside the general assemblies.

I got together with some friends I had known and trusted for a long time—the same group that had called for Occupy in our town in the first place. We discussed whether to occupy a vast empty building a few blocks from the plaza. Most of us thought it was impossible, but a few fanatics insisted it could be done. We decided that if they could get us inside, we would try to hold onto it. But the plan had to be a secret until we were in, so the police couldn’t stop us.

The building occupation was a success. Over a hundred people flooded into the building, setting up a kitchen, a reading library, and sleeping quarters. A band performed, followed by a dance party. That night, dozens of people slept in the building rather than at the plaza, relieved to be out of the cold. Once again, I stood watch all night, waiting for the police—the stakes were higher this time, but they didn’t show up. Spirits were high: once again, we had expanded the space of possibility.

The following afternoon, as we continued cleaning and repairing the building, a rumor circulated that the police were preparing a raid. Several dozen of us gathered for an impromptu meeting. It struck me how different the atmosphere was from our usual general assemblies. There were no bureaucratic formalities, no deadlocks over minutia. No one droned on just to hear himself speak or stared off listlessly. There was no payoff for grandstanding or chiding each other about protocol.

Here, there was nothing abstract about the issues at hand. We were putting our bodies on the line just by being present; these were real choices that would have immediate consequences for all of us. We didn’t need a facilitator to listen to each other or stay on topic. With our freedom at stake, we had every reason to work well together.

The day after the raid, a huge crowd gathered at the original encampment for a contentious general assembly—the biggest and most energetic our town witnessed throughout the entire sequence of Occupy. Our decision to occupy the building, arrived at outside the general assembly, had ironically made the general assembly irresistible to everyone. Some people were inspired by the building occupation and our response to the police raid; others, who assumed the general assembly to be the governing body of the movement, were outraged that we had bypassed it; still others, who had not been interested in Occupy until now, came to engage with us because they could see we were capable of making a big impact. Even if they were only there to argue that we should “be peaceful” and obey the law, we hoped that entering that space of dialogue might expand their sense of what was possible, too.

So the assembly benefitted from the building occupation, whether or not people approved of it. But they only came because of the power we had expressed by acting on our own. It was this power that they sought to access through the assembly—some to increase it, some to command it, some to tame it. In fact, the power didn’t reside in the assembly as a decision-making space, but in the people who came to it and the connections they forged there.

Over the following week, people inspired by the building occupations in Oakland and our little town occupied buildings in St. Louis, Washington, DC, and Seattle. This new wave of actions pushed the Occupy movement from symbolic protests towards directly challenging the sanctity of capitalist notions of property. Our town saw its biggest unpermitted demonstrations in years.

Months later, I compared notes with comrades around the country about how this mass experiment in consensus process had gone. Everywhere, there had been the same conflicts, as some people who saw the assemblies as the legitimate space of decision-making criticized those who propelled the movement forward for acting autonomously. Even in Oakland, the most confrontational encampment in the country, they never made a consensus decision to keep police out of the camp—that decision was made by individuals, independently. A friend from Oakland recounted to me how, when he prevented an officer from entering, a young reformist who had just learned the buzzwords of consensus process angrily shouted “I block you, man! I block you!” at him. In a photograph taken after the riots with which occupiers retaliated against the eviction of their encampment, someone has written on a broken window, “This act of vandalism was NOT authorized by the GA,” as if the GA were a governmental body, answerable for its subjects and therefore entitled to legitimize or delegitimize their actions.

That shows a profound misunderstanding of what consensus procedure is good for. Like any tool, power flows from us to it, not the other way around—we can invest it with power, but using it won’t necessarily make us more powerful. Every single step that made Occupy succeed in our town, from the call for the first assembly to the decision to occupy the plaza to the decision to occupy a building, was the result of autonomous initiative. We never could have consensed to do any of those things in an assembly that included anarchists, Maoists, reactionary poor people, middle-class liberals, police infiltrators, people with mental health issues, aspiring politicians, and whoever else happened to stop by at random. The assemblies were essential as a space where we could intersect and exchange proposals, creating new affinities and building a sense of our collective power, but we don’t need a more participatory—and therefore even more inefficient and invasive—form of government. We need the ability to act freely as we see fit, the common sense to coexist with others wherever possible, and the courage to stand up for ourselves whenever there are real conflicts.

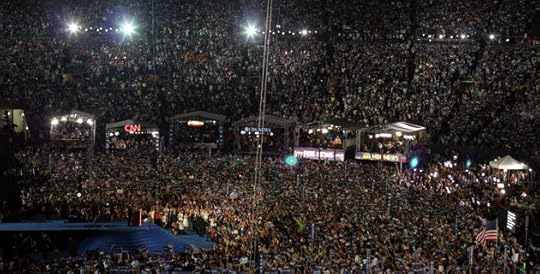

As the movement was dying down, the faction of Occupy that was most invested in legalism and protocol called for a National Gathering in Philadelphia on July 4, 2012, at which to “collectively craft a Vision of a Democratic Future.” Barely 500 people showed from around the country, a tiny fraction of the number that had blocked ports, occupied parks, and marched in the streets. The people, as they say, had voted with their feet.

April 7, 2016

Destination Anarchy/Every Step Is an Obstacle

In summer 2011, tens of thousands of people came together in Syntagma Square in front of the Greek parliament in Athens to express a complete rejection of the government and experiment with direct democracy. At the high point of the protests, over a hundred thousand people clashed with the authorities. Years later, many of the people who flooded Syntagma have poured into the ranks of the ruling party, Syriza, or the fascist party Golden Dawn. In this reflective account, a Greek anarchist narrates the events of 2011 and the developments since then, illustrating the ways that one day’s steps towards liberation become the next day’s obstacles and drawing out the questions that anarchists will have to answer to open the way to freedom.

This text is an installment in a series exploring the anarchist analysis of democracy, tracing the trajectories of directly democratic movements around the world.

April 5, 2016

From 15M to Podemos

In May 2011, protesters inspired by the Arab Spring occupied plazas across Spain in lively anti-government demonstrations centered around directly democratic assemblies. This was the first of a wave of such movements that spread across Europe and the world. Five years later, the energy that began as a push for participatory politics has been channeled into the rise of new Spanish political parties. Is this a corruption of the discourse of the plaza occupation movement, or its logical conclusion?

This eyewitness account is an installment in our series exploring the anarchist analysis of democracy.

March 31, 2016

From Democracy to Freedom

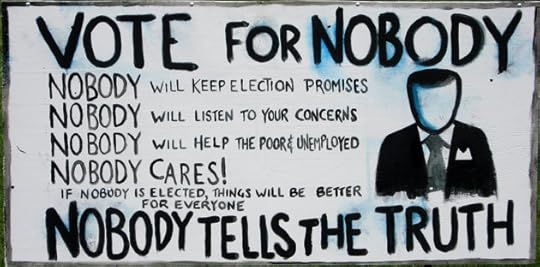

Billions around the world have watched the familiar pageantry of the US Presidential race: Trump, the champion of the new extreme right, laying the groundwork for the despotism to come; Sanders, the partisan of an impossible dream, who nonetheless succeeded in luring disaffected millions back into electoral politics; Clinton, the despised representative of the status quo—around whom the hapless majority are forced to rally, since the future is sure to be even worse. Contemplating this bleak spectacle, some people object that this isn’t real democracy.

This talk about real democracy will be familiar to anyone who lived through the Occupy movement or one of its overseas equivalents. In 2011, from Tunis to Madrid and New York, movements triggered by the economic crisis turned into experiments with new forms of governance. By 2014, the luster of real democracy had begun to wear off: the Ukrainian revolution confirmed the right-wing appropriation of the discourse, while the movement that spread from Ferguson began with a riot, not an assembly. But next time revolution is on the agenda, we’ll surely hear more calls for “real” democracy. As long as democracy is the only paradigm we have for change, even anarchists will demand it.

Reflecting on the revolts of the preceding decade, we decided it was high time to get to the bottom of what democracy really is—and whether it’s what we want, after all. After years of research, discussion, and experimentation, we are excited present our conclusions in a massive new feature: From Democracy to Freedom.

In this text, we examine the common threads that connect different forms of democracy, trace the development of democracy from its classical origins to its contemporary representative, direct, and consensus-based variants, and evaluate how democratic discourse and procedures serve the social movements that adopt them. Along the way, we outline what it could mean to seek freedom directly rather than through democratic rule.

This is the flagship text in a series we will be publishing over the next several weeks, including testimony and critical analysis from participants in directly democratic movements around the world.

March 16, 2016

Series: The Anarchist Critique of Democracy

What is democracy, precisely? Will it ever deliver on what it promises? How significant is the difference between state democracy and direct democracy? Is anarchism a kind of direct democracy, or something else entirely? And how do democratic discourse and procedures serve the social movements that adopt them?

This month, we’re publishing a ten-part series exploring these questions, presenting an anarchist analysis of democracy in all its forms. The flagship text, “From Democracy to Freedom,” traces democracy from its origins up to today, examining its representative, direct, and consensus-based variants. We’ll follow up with case studies from participants in several of the recent movements that have been acclaimed as models of direct democracy: 15M in Spain (2011), the occupation of Syntagma Square in Greece (2011), Occupy in the United States (2011-2012), the Slovenian uprising (2012-2013), the plenums in Bosnia (2014), and the Rojava revolution (2012-2016). We’ll conclude the series with guest contributions on the subject from Paul Z. Simons, Uri Gordon, and others.

To kick off the series, we’ve prepared an updated online version of our classic text on this subject, The Party’s Over. We also encourage everyone to read the English translation of Contra la Democracia (“Against Democracy”) from Spain. Here’s an incomplete syllabus for the next two weeks:

The Party’s Over

From Democracy to Freedom

From 15M to Podemos: The Regeneration of Spanish Democracy

Destination Anarchy! Every Step Is an Obstacle (Syntagma)

Democracy and Autonomy in the Occupy Movement

From Occupy to Uprising: Experiments with Direct Democracy in Slovenia

Born in Flames, Died in Plenums: The Bosnian Experiment with Direct Democracy

Lessons from Rojava: Democracy and Commune (Paul Z. Simons)

Democracy: The Patriotic Temptation (Uri Gordon)

You’re invited to form a reading group to participate in this project! We will be setting up a discussion platform where groups around the world can compare notes on the texts and the topic itself, in hopes of drawing on the conversation for a future episode of the Ex-Worker podcast. If you’re interested, get together some friends and write us at rollingthunder@crimethinc.com for details—or stay tuned here for a more detailed update shortly.

Further Reading

Democracy’s Bankrupt

Contra la Democracia

Malatesta: Neither Democrats, nor Dictators: Anarchists and Democracy and Anarchy

#47: The Anarchist Critique of Democracy

#47: Introducing the Anarchist Critique of Democracy — Is Democracy what we’re fighting for, as anarchists? In episode 47 of the Ex-Worker Podcast, a contentious debate between Clara and Alanis on this topic sets the stage for an upcoming, in-depth engagement with the topic of Democracy. In addition, we clean out our backlog of listener feedback, clarifying our trash-talking of both the Bay Area and Adbusters in past episodes, as well as hearing from a listener in Australia about various online resources for finding out what’s happening with anarchist and anti-fascists in the land down under. NYC Anarchist Black Cross provides us with thorough political prisoner updates, and we share a review of the book Huye Hombre Huye, available from Little Black Cart. As always, the episode is bookended with global news updates, plus prisoner birthdays, a whole slew of upcoming anarchist bookfairs and other events and more.

You can download this and all of our previous episodes online. You can also subscribe in iTunes here or just add the feed URL to your podcast player of choice. Rate us on iTunes and let us know what you think, or send us an email to podcast@crimethinc.com. You can also call us 24 hours a day at 202–59-NOWRK, that is, 202–596–6975.

February 24, 2016

Rolling Thunder #10 PDF Now Available

This morning we sent out the last copy of Rolling Thunder #10, and you know what that means—the full high-resolution RT#10 PDF is now available for free download. This issue was two years in the making and absolutely jampacked:

Rolling Thunder #10 begins with a reappraisal of the anarchist project in today’s context of crisis and technological transformation. From there, we chart the global trajectory of momentum from 2010 to 2012: the student movements in the US and UK—the insurrections in Tunisia, Egypt, and beyond—the occupation movements in Spain, Greece, and finally the USA, from its awkward beginnings in Wisconsin to its aftereffects in Oakland. For case studies, we focus in on the anti-police struggles that catalyzed the rise of confrontational anarchism in Seattle, and scrutinize how US immigration policy is applied on the ground at the border to explain how its actual objectives differ from its ostensible purpose. The issue concludes with a historical review of Canadian anarchism, following it from its origins through the 2010 Olympics and G20 riots and up to the present day. All this, plus a graphic history from Argentine anarchism, 24 pages in full color, and all the other bells and whistles you’ve come to expect from us times two. (114 pages)

Last month we added Rolling Thunder #12 (the most current issues) to the Rolling Thunder Bundle, which now contains issues #8, #11, and #12 for just $10. And, don’t forget, you can subscribe to Rolling Thunder to get future issues hot off the press, while also supporting the project and ensuring the journal’s continued existence.

CrimethInc.'s Blog

- CrimethInc.'s profile

- 267 followers