Austin Ratner's Blog, page 10

April 28, 2011

On My Grudging Disrespect for Nabokov and His Cheval Mirror

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov

Pale Fire by Vladimir NabokovI recently returned to Pale Fire after leaving it unfinished over ten years ago. I returned not least because the sage Robert Alter commended it and quoted from it this brilliant passage on mirrors:

He awoke to find her standing with a comb in her hand before his--or rather, his grandfather's--cheval glass, a triptych of bottomless light, a really fantastic mirror, signed with a diamond by its maker, Sudarg of Bokay. She turned about before it: a secret device of reflection fathered an infinite number of nudes in its depths, garlands of girls in graceful and sorrowful groups, diminishing in the limpid distance, or breaking into individual nymphs, some of whom, she murmured, must resemble her ancestors when they were young--little peasant garlien combing their hair in shallow water as far as the eye could reach, and then the wistful mermaid from an old tale, and then nothing. pp. 111-112.

The 999-line poem in heroic couplets that begins Pale Fire is a technical achievement with many stirring images (like the first one, which has long been stuck in my head: “I was the shadow of the waxwing slain / By the false azure in the windowpane”). But I had not understood the conceit that makes up the rest of the book: the fictional academic Charles Kinbote annotates the poem, which is by his neighbor John Shade, and Kinbote’s endnotes have little to do with the poem and more to do with Kinbote’s bizarre remembrances of his homeland, a Baltic kingdom called Zembla. But according to Alter, the two parts of the book are in fact connected. Alter suggests that the commentaries should be read as a distorted reflection of the poem, Kinbote as a distorted reflection of Shade, both figures as distorted reflections of their creator, Nabokov. Alter points out that while Nabokov has drawn Kinbote as a farcical figure, he’s also just like Nabokov in an important way: he’s a fugitive from his homeland, living out his post-exilic life in the United States, haunted by nostalgia for his home. (Nabokov’s family fled Russia in 1919, when he was 20, in order to escape the Bolshevik Revolution.) On pp. 191-192 of Partial Magic, Alter’s study of the self-conscious novel, he comments on Nabokov’s passage on the cheval mirror (which is a full-length tilting mirror on a stand, or 'horse,' thus 'cheval'):

[C]onsciousness, as the example of Joyce’s technique must remind us, is essentially built up out of the infinite laminations of what the individual has seen, felt, read, fantasized in the past, however attuned he may be to the present moment. The mirror itself here is a legacy of the past, not properly King Charles’s but his grandfather’s…. [A]s she [Fleur] observes herself transfigured in multiple reflection, we are moved further back in time into a legendary past where pastoral ancestors preen themselves by still waters.

It began to seem to me that Pale Fire was an examination of the structure of consciousness as a sort of cheval mirror: consciousness reflects reality but also tips it in its own direction, according to its own machinery. If the commentaries were meant to mirror the poem and Kinbote to mirror Shade, I thought, then perhaps Pale Fire was really as brilliant as its adherents said. Maybe the poem part of the book was meant to be the naturalistic and conscious way of seeing and reflecting reality, while Kinbote’s farcical commentaries were meant to be an expressionistic way of seeing and reflecting the same thing. And in that case, maybe all that crazy rambling in the commentaries had a real meaning. Maybe all the mirrors everywhere in the book were not postmodern symbols of infinite regression to nothing, but rather modernist symbols of the multiplicative meaning-making powers of the mind and of art. (I alliterate in mirroring deference to Nabokov's style--and because it just came out that way.) So, armed with 40 pages of Alter’s interpretations, I went back to Pale Fire with renewed enthusiasm and note-taking pen in hand.

Mirrors were in fact everywhere, starting with the title, Pale Fire. Alter points out that Nabokov borrowed the phrase from a passage in Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens, Act IV sc iii, ll. 440-441: “…the moon’s an arrant thief, / And her pale fire she snatches from the sun….” He points out that the name of the glassmaker referred to in the passage above, Sudarg of Bokay, is a near mirror image of the name of the assassin who pursues Kinbote throughout his semi-fantastical memories: Jakob Gradus. It occurred to me, furthermore, that the name of Kinbote’s fantastical kingdom, Zembla, must be derived from the word ‘resemble.’

I was excited about all those mirrors as I read and hunted for meanings in their reflections. I confess, however, that what had seemed elegant, artful, beautiful, and meaningful in Alter’s account, was upon actual reading elegant, yes, artful and beautiful, yes, but mostly not very meaningful and on top of that extremely tedious and irritating. While both Kinbote and Shade have lost their parents prematurely, Nabokov does very little with this subject, or any other of psychological importance to his characters, and instead scatters his attention in a million different directions, introducing new characters every other page.

I wanted to like Nabokov. He has Joyce’s gift for allusion and Woolf’s poetic sense. But in my view—a view that could be wrong, but derives at least from serious consideration—Nabokov lacks the courage and character of both of his modernist forebears. He can’t sustain his gaze on the complexities of reality for the duration of an entire novel, but would rather spin the mirror around and around. I suspect that if he let it come to rest, he’d see something he didn’t want to see.

View all my reviews

Published on April 28, 2011 12:32

April 18, 2011

In Pursuit of Tranquillity

Hellenistic Philosophy: Introductory Readings by Brad Inwood

Hellenistic Philosophy: Introductory Readings by Brad InwoodA.D. Nuttall, the Oxford literature professor, has observed that ancient philosophy falls into two periods--the first being that of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, the second being the generation that followed: Epicurus, Zeno (father of Stoicism), skeptics like Pyrrho, and others. Socrates died in 399 B.C.E., but the rest lived and wrote mostly in the 4th century B.C.E. (I mean the 300s B.C.E.). "Hellenistic Philosophy" refers to this post-Aristotelian group, whose ideas, like those of their forebears, were spread far and wide by the Romans. Few of Epicurus's many works are extant and Pyrrho, for reasons that will become evident if you read about his philosophy, refused to write anything down--an approach that would have been preferable in the work of a great many other philosophers. Consequently, much of what is known of the Hellenistic philosophers comes down to us through the Roman commentators like Diogenes Laertius, and it's these commentaries which make up most of the texts in Inwood and Gerson's anthology.

Nuttall writes of the Hellenistic philosophers, "In the second period a strange alteration comes over the philosophers: they now present themselves as purveyors of mental health. It is as if some immense failure of nerve, a kind of generalized neurosis, swept through the ancient world, so that the most serious thinkers found that their most urgent task was not to inform or enlighten but to heal. They begin to sound like psychiatrists." They promise ataraxia, that is, tranquillity. (It looks more promising in the original Greek characters.)

Does anybody read this stuff anymore? They should. The proffered path to tranquillity differs greatly between philosophers; Epicurus urges understanding through study and analysis of nature--methods that would later be called science. He feels this is the way to dispel anxiety and fear and achieve tranquillity (there is little in the actual philosophy of Epicurus to do with hedonism per se). Other philosophers seek relief from reality in skeptical denial of it or in a denial of one's passions (homey don't play that).

The dialectic between knowledge and denial, these differing strategies of mental pain management, is still unfolding. As Wolverine of the X-Men says, "There's a war coming. Are you sure you're on the right side?"

Published on April 18, 2011 19:16

In Pursuit of Tranquillity

Hellenistic Philosophy: Introductory Readings by Brad Inwood

Hellenistic Philosophy: Introductory Readings by Brad InwoodMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

A.D. Nuttall, the Oxford literature professor, has observed that ancient philosophy falls into two periods--the first being that of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, the second being the generation that followed: Epicurus, Zeno (father of Stoicism), skeptics like Pyrrho, and others. Socrates died in 399 B.C.E., but the rest lived and wrote mostly in the 4th century B.C.E. (I mean the 300s B.C.E.). "Hellenistic Philosophy" refers to this post-Aristotelian group, whose ideas, like those of their forebears, were spread far and wide by the Romans. Few of Epicurus's many works are extant and Pyrrho, for reasons that will become evident if you read about his philosophy, refused to write anything down--an approach that would have been preferable in the work of a great many other philosophers. Consequently, much of what is known of the Hellenistic philosophers comes down to us through the Roman commentators like Diogenes Laertius, and it's these commentaries which make up most of the texts in Inwood and Gerson's anthology.

Nuttall writes of the Hellenistic philosophers, "In the second period a strange alteration comes over the philosophers: they now present themselves as purveyors of mental health. It is as if some immense failure of nerve, a kind of generalized neurosis, swept through the ancient world, so that the most serious thinkers found that their most urgent task was not to inform or enlighten but to heal. They begin to sound like psychiatrists." They promise ataraxia, that is, tranquillity. (It looks more promising in the original Greek characters.)

Does anybody read this stuff anymore? They should. The proffered path to tranquillity differs greatly between philosophers; Epicurus urges understanding through study and analysis of nature--methods that would later be called science. He feels this is the way to dispel anxiety and fear and achieve tranquillity (there is little in the actual philosophy of Epicurus to do with hedonism per se). Other philosophers seek relief from reality in skeptical denial of it or in a denial of one's passions (homey don't play that).

The dialectic between knowledge and denial, these differing strategies of mental pain management, is still unfolding. As Wolverine of the X-Men says, "There's a war coming. Are you sure you're on the right side?"

View all my reviews

Published on April 18, 2011 18:06

April 10, 2011

The Greatness of George Eliot

Middlemarch by George Eliot

Middlemarch by George EliotMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

"That greatness is here we can have no doubt," Virginia Woolf wrote of George Eliot in 1919, a century after Eliot was born (and christened with the name Mary Anne Evans). "[A]s we recollect all that she dared and achieved ... we must lay upon her grave whatever we have it in our power to bestow of laurel and rose." It's a fitting eulogy for one of the greatest English novelists of the 19th century. Though Woolf criticized Eliot as sometimes verbose and inelegant, she also rightly proclaimed Middlemarch "the magnificent book which with all its imperfections is one of the few English novels written for grown-up people." Rebecca Mead, writing in The New Yorker adds that it's "also a book about how to be a grownup person--about how to bear one's share of sorrow, failure, and loss, as well as to enjoy moments of hard-won happiness." Though Eliot was hugely famous in her lifetime, and to my mind deserved every bit of it, she wrote straight-out against fame. She was just too wise and experienced to believe that the world justly rewards merit. The characters of Middlemarch clearly have merit--they have moral fiber and they have genius, even--but their merit usually exceeds what they're recognized to have achieved. Lydgate, for instance, is a young doctor whose brilliant thinking brings him close to the discovery of the cell as one of the organizing principles of life. He doesn't discover it, but it's no fault of his. He isn't a tragic figure ruined by his vices. He's a hero. He's the hero with whom history wouldn't cooperate.

The authors of the Hebrew Bible, Homer, Tolstoy, George Eliot: these writers know well the unpredictable wooly mammoth that is history, an animal that's bigger than the human will. The human will plays a part, yes, but time, history, physics, accident, these unfeeling inhuman forces have equal power over human destiny. Of her character Mary Garth, Eliot writes, "having early had strong reason to believe that things were not likely to be arranged for her peculiar satisfaction, she wasted no time in astonishment and annoyance at that fact." (p. 349) And the proximity of other human wills holds powerful sway over an individual's fortunes. Eliot examines the institution of marriage as a case study of such influence of one person on another, an influence that can be both enlarging and delimiting. "In half an hour he left the house an engaged man, whose soul was not his own, but the woman's to whom he had bound himself," she writes of Lydgate (p. 336). Society, too, looms large as a potential frustration to the individual will--society, with all its lies and errors. All these forces arrayed against the vulnerable little wishes of the human individual seem to combine in Eliot’s mind to inspire the final lines of her masterpiece, Middlemarch:

Certainly those determining acts of her life were not ideally beautiful. They were the mixed result of young and noble impulse struggling amidst the conditions of an imperfect social state, in which great feelings will often take the aspect of error, and great faith the aspect of illusion. For there is no creature whose inward being is so strong that it is not greatly determined by what lies outside it. A new Theresa will hardly have the opportunity of reforming a conventual life, any more than a new Antigone will spend her heroic piety in daring all for the sake of a brother’s burial: the medium in which their ardent deeds took shape is forever gone. But we insignificant people with our daily words and acts are preparing the lives of many Dorotheas, some of which may present a far sadder sacrifice than that of the Dorothea whose story we know.

Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

Developmental biology seems to function as a controlling metaphor for Eliot in this account of life. (Her ability to integrate disparate characters and storylines through sustained metaphor is one of her great attributes as a writer.) In her prose embryonic potential everywhere meets a world that is foreign to it and that directs its growth as the soil and light direct the growth of a tree.

So we do what we can, and have George Eliot to console us about the frustration, the unfairness, the despair—and also to inspire us with the greatness that ambition and accumulated skill can truly achieve, even in a complex and unaccommodating world. She avers the power of the human will, particularly as it manifests itself in language, by her example of course, but also more directly: “The right word is always a power, and communicates its definiteness to our action,” she writes not six lines from her somewhat pessimistic account of Lydgate’s engagement on p. 336. It’s up to us to speak and act with definite purpose. The world’s reaction is not our affair.

View all my reviews

Published on April 10, 2011 20:53

The Greatness of George Eliot

Middlemarch by George Eliot

Middlemarch by George Eliot"That greatness is here we can have no doubt," Virginia Woolf wrote of George Eliot in 1919, a century after Eliot was born (and christened with the name Mary Anne Evans). "[A]s we recollect all that she dared and achieved ... we must lay upon her grave whatever we have it in our power to bestow of laurel and rose." It's a fitting eulogy for one of the greatest English novelists of the 19th century. Though Woolf criticized Eliot as sometimes verbose and inelegant, she also rightly proclaimed Middlemarch "the magnificent book which with all its imperfections is one of the few English novels written for grown-up people." Rebecca Mead, writing in The New Yorker adds that it's "also a book about how to be a grownup person--about how to bear one's share of sorrow, failure, and loss, as well as to enjoy moments of hard-won happiness." Though Eliot was hugely famous in her lifetime, and to my mind deserved every bit of it, she wrote straight-out against fame. She was just too wise and experienced to believe that the world justly rewards merit. The characters of Middlemarch clearly have merit--they have moral fiber and they have genius, even--but their merit usually exceeds what they're recognized to have achieved. Lydgate, for instance, is a young doctor whose brilliant thinking brings him close to the discovery of the cell as one of the organizing principles of life. He doesn't discover it, but it's no fault of his. He isn't a tragic figure ruined by his vices. He's a hero. He's the hero with whom history wouldn't cooperate.

The authors of the Hebrew Bible, Homer, Tolstoy, George Eliot: these writers know well the unpredictable wooly mammoth that is history, an animal that's bigger than the human will. The human will plays a part, yes, but time, history, physics, accident, these unfeeling inhuman forces have equal power over human destiny. Of her character Mary Garth, Eliot writes, "having early had strong reason to believe that things were not likely to be arranged for her peculiar satisfaction, she wasted no time in astonishment and annoyance at that fact." (p. 349) And the proximity of other human wills holds powerful sway over an individual's fortunes. Eliot examines the institution of marriage as a case study of such influence of one person on another, an influence that can be both enlarging and delimiting. "In half an hour he left the house an engaged man, whose soul was not his own, but the woman's to whom he had bound himself," she writes of Lydgate (p. 336). Society, too, looms large as a potential frustration to the individual will--society, with all its lies and errors. All these forces arrayed against the vulnerable little wishes of the human individual seem to combine in Eliot's mind to inspire the final lines of her masterpiece, Middlemarch:

Certainly those determining acts of her life were not ideally beautiful. They were the mixed result of young and noble impulse struggling amidst the conditions of an imperfect social state, in which great feelings will often take the aspect of error, and great faith the aspect of illusion. For there is no creature whose inward being is so strong that it is not greatly determined by what lies outside it. A new Theresa will hardly have the opportunity of reforming a conventual life, any more than a new Antigone will spend her heroic piety in daring all for the sake of a brother's burial: the medium in which their ardent deeds took shape is forever gone. But we insignificant people with our daily words and acts are preparing the lives of many Dorotheas, some of which may present a far sadder sacrifice than that of the Dorothea whose story we know.

Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

Developmental biology seems to function as a controlling metaphor for Eliot in this account of life. (Her ability to integrate disparate characters and storylines through sustained metaphor is one of her great attributes as a writer.) In her prose embryonic potential everywhere meets a world that is foreign to it and that directs its growth as the soil and light direct the growth of a tree.

So we do what we can, and have George Eliot to console us about the frustration, the unfairness, the despair—and also to inspire us with the greatness that ambition and accumulated skill can truly achieve, even in a complex and unaccommodating world. She avers the power of the human will, particularly as it manifests itself in language, by her example of course, but also more directly: "The right word is always a power, and communicates its definiteness to our action," she writes not six lines from her somewhat pessimistic account of Lydgate's engagement on p. 336. It's up to us to speak and act with definite purpose. The world's reaction is not our affair.

Published on April 10, 2011 19:15

April 4, 2011

From Fish to Philosopher

From Fish to Philosopher by Homer William Smith

From Fish to Philosopher by Homer William SmithMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

"Urine is the stuff of philosophy," says Homer Smith. And if you read him, you'll agree. In fact, I believe every person who wants to understand fully what a living thing is, what a human being is, should read this book.

Published in the 1950s and reissued in 1961 by the American Museum of Natural History in New York--now a very rare book--this is the best treatise I know on the development of life on earth. It's a physiologist's history of the evolution of the organs, with special attention to the kidney, and if you read it you'll understand why the kidney gets top billing. (The kidney is the principal organ of homeostasis--look it up.) While this is biology in the form of a thrilling odyssey through time, I'll also warn you that Smith doesn't shy away from full explanation and detail; that may make parts of it daunting or in some cases inaccessible without certain ancillary studies in physiology. (But do those popular simplifications ever make any sense anyway?) That said, it's nothing like those arrogant tracts in wall-to-wall math symbols I get through those Scientific American deals. I think Smith works in an ideal middle ground, where he doesn't condescend to his readers by imagining that they can't understand what he does, and yet writes clearly and comprehensibly. He writes well-enough not to have to pretend that the English language is insufficient to convey all he knows. His style influenced me in the writing of my physiology text.

Called "a broad epic of life" by George Gaylord Simpson, a Harvard paleontologist who is by now likely a fossil himself, From Fish to Philosopher explains how we got the way we are, how our bodies and our minds too, derive from and record a long, long history of adaptation to the conditions of this crust of earth we call home.

You can download it for free or read it online here: http://www.archive.org/details/fromfisht...

View all my reviews

Published on April 04, 2011 12:54

March 26, 2011

Weird Science

Frankenstein (Signet Classics) by Mary Shelley

Frankenstein (Signet Classics) by Mary ShelleyMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

This question hovers over the novel’s outrageous plot: why would Victor Frankenstein abandon his creation? It doesn’t really make much sense unless you appeal to the open secrets of Mary Shelley’s biography. Her mother died of puerperal sickness (i.e., after childbirth), abandoning her daughter Mary to a lifetime without her. The monster’s undiminished rage at his absent creator seems to me obviously to parallel Shelley’s childhood situation and what she could be expected to feel. And yet Shelley’s sympathies are neatly divided between the monster and its creator. She knew the monster’s loneliness and sense of exile but also knew Victor Frankenstein’s longing to resurrect; her first child Clara died in infancy and, according to editor of the Signet edition Walter James Miller, she had recurrent dreams of reviving the child. She knew Victor Frankenstein’s hatred for his own creation as well. Clara died—cause enough for fury—but her second child, William, survived, and as any honest parent knows, that’s problematic too. It’s no coincidence, is it, that the monster’s first act of violence is to strangle to death a little boy named … William?

The novel Frankenstein is the child of generational tension just as Hamlet is, but Frankenstein is a child of more extreme and premature abandonment, of an infant‘s rage against her absent mother and a mother’s rage at her infant’s hounding, stalking needs (rage at “the murderer of my peace” as Frankenstein puts it on p. 147). Indeed, one of the most remarkable things about Frankenstein is its focus on infancy and its psychological residua. Miller tells us that prior to writing Frankenstein, Shelley read John Locke’s Essay on Human Understanding—an important precursor to modern notions of child development according to which experience shapes the naïve, plastic tissues of the infant brain and leaves a permanent imprint on a person’s identity.

Explicit references to infancy and its relation to later life bestrew the pages of Frankenstein. From the beginning, as Captain Walton recounts the tale of his “earlier years” (p. 13) and Victor Frankenstein tells the tale of his, Shelley asserts that the past ruthlessly determines the future. “[N]othing can alter my destiny,” Frankenstein says on p. 15, “listen to my history, and you will perceive how irrevocably it is determined.” The personal histories of such importance to Shelley also return again and again to certain themes—of orphanhood, abandonment, death in childbirth, etc., and consequent insecurity and loneliness. The monster’s inquiry into his early life is the most affecting of all. On p. 84 he says, “It is with considerable difficulty that I remember the original era of my being….” On p. 101 the monster says, “No father had watched my infant days, no mother had blessed me with smiles and caresses.”

Early impressionability and want of love lead directly to the two other major motives of the novel: rage and guilt, tormenting guilt and unrelieved rage. When the monster realizes he is alone in the world without a single friend, he says (on p. 116), “[F]rom that moment I declared everlasting war … against him who had formed me and sent me forth to this insupportable misery.”

Mary Shelley attacks these unusual themes with unparalleled intellect and imagination. Some of her descriptions, particularly of the Swiss Alps, are divine, but on the whole her prose does not serve her well. It could be argued that the prose of the entire era was in general spoiled with twee Wordsworthian excess, but whatever the cause—the era or Shelley’s youth or whatever—there are long tracts of Frankenstein written in butter cream fondant. Here’s a passage, for example, that goes on and on and says little. Frankenstein wants to tell his father that he’s going to London as a tourist, as opposed to going there on a secret mission to create a woman, in hopes of compelling his male creation to stop murdering his relatives. He says:

I expressed a wish to visit England, but concealing the true reasons of this request, I clothed my desires under a guise which excited no suspicion, while I urged my desire with an earnestness that easily induced my father to comply. After so long a period of an absorbing melancholy that resembled madness in its intensity and effects, he was glad to find that I was capable of taking pleasure in the idea of such a journey, and he hoped that change of scene and varied amusement would, before my return, have restored me entirely to myself. pp. 131-132

I’m forced to conclude that at that early stage of novel-writing, authors didn’t fully appreciate the uses of dialogue. Wouldn’t that wordy, explanatory paragraph have been improved by something like this:

“I’m going to England,” I said. “It’s Bonfire Night approaching. Clerval says it’s not to be missed.”

“By all means,” my father said. “Absolutely, you should go. It will do you good!”

“They have marvelous fireworks on the Thames, Clerval says.”

“Yes, yes, go!”

And I went on behalf of the monster, and I saw no fireworks.

With much of the prose so painfully verbose and frequently irrelevant, I find it all the more amazing how well Shelley succeeds with the parts focused on the monster himself, especially what Harold Bloom calls “the novel’s extraordinary conclusion, with its scenes of obsessional pursuit through the Arctic wastes….” Her nameless monster is one of the most moving, pitiable, unsettling, and unique characters in all literature, a character to make you weep like the Elephant Man, like no Shakespeare character makes you weep, except perhaps Othello. And Shelley’s “demonic conclusion in a world of ice,” as Harold Bloom puts it, is a picture of crucifixion by total loneliness, helplessness, guilt, and rage, more tragic than anything else I’ve read in a work of fiction.

View all my reviews

Published on March 26, 2011 20:12

March 17, 2011

Winnie the Pooh

Winnie the Pooh by A.A. Milne

Winnie the Pooh by A.A. MilneMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

Many books and movies for children are also entertaining to adults. A.A. Milne's work, conversely, is profoundly absorbing (and hilarious) for adults, and also, secondarily, diverting to kids. It also scrupulously safeguards a G-rating by omitting direct reference to death, sex, and other nether body functions--though every child wonders, at least in passing, how grown-ups in polite company can call a bear "Poo," and why they would want to.

Milne's characters are so real that you never cease to believe in them even when the frame story apparatus frankly proclaims them inventions concocted by a father for his son--even when, over pancakes in Orlando, you confront a totally mute man in a giant Tigger costume at a Disneyworld "character breakfast."

Pooh, Piglet, Owl, Rabbit, and Eeyore busy themselves in systematically misunderstanding the world in the charming way that children do, and in such a way that only an adult is in on the joke. They're stories about children, and about the childlike nature that endures inside of adults, more than they're stories for children, I think. And in that, they're somewhat radical and unique. But then again, I didn't read them as a child.

My older one never got into these much, not even the Disney version. My younger one will listen contentedly for long stretches but misunderstands them in the same way that Piglet might. I read him the chapter "In Which Christopher Robin Leads an Expotition to the North Pole" and I laughed when they find the Pole (a tree branch) and Eeyore says, "Oh! Well, anyhow--it didn't rain," rating the mission a success therefore according to the dim lights of low expectation. My four-year-old son heard me laugh and said wisely, "That's funny because it doesn't rain at the North Pole, it snows."

All that said, the deep-seated wholesomeness of the Hundred Acre Wood is somehow just right for some kids, like my four-year-old, even if he doesn't understand all the jokes. And once I explained some of the humor in chapter IV ("In Which Eeyore Loses a Tail and Pooh Finds One")--such as Owl and Pooh's argument over whether or not Owl sneezed, and Pooh's asking Owl for help and then not listening and thinking to himself that he'd like a lick of honey--once I explained why I was laughing, we had a good hearty laugh over it together.

View all my reviews

Published on March 17, 2011 21:26

February 25, 2011

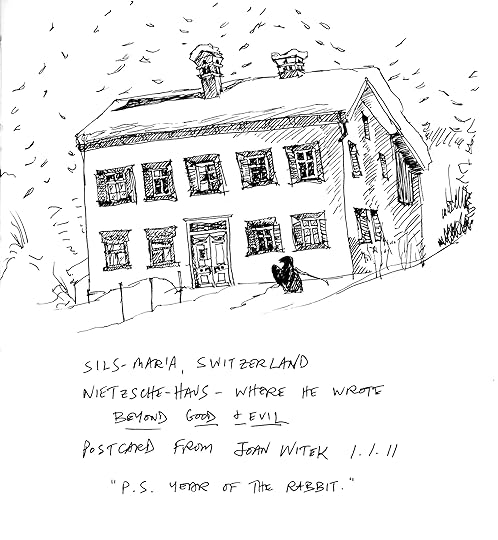

A Postcard from Nietzsche's Haus

My blog this week, on Nietzsche, savagery, self-destruction, Lake Sils, Anne Frank, and stones in umbrellas, appears here, at writershouses.com. This is one of my best essays, on one of the best essayists of all time.

My blog this week, on Nietzsche, savagery, self-destruction, Lake Sils, Anne Frank, and stones in umbrellas, appears here, at writershouses.com. This is one of my best essays, on one of the best essayists of all time.

Published on February 25, 2011 08:35

February 18, 2011

Ten Days of War and Peace

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy

War and Peace by Leo TolstoyMy rating: 5 of 5 stars

"I only know two very real evils in life: remorse and illness," Prince Andrei says to Pierre in War and Peace. Life torments from within and without, according to Tolstoy, who, like the writers of the Hebrew bible, compasses the innermost human thoughts adrift in the chaos and cosmic rancor of history.

I'm not a quick reader but I read War and Peace in ten days the February of my sophomore year of college. I had to write a paper on it, due shortly after the end of spring break, and left it to the last minute. Each morning I crawled into the nubby gray womb chair in my parents' living room, by a plate-glass window where mammoth icicles hung and birds occasionally broke their necks. (Poems come to mind: "barbaric glass" and "I was the shadow of the waxwing slain / By the false azure in the windowpane.") I made it my job to read 120 pages a day, pen in hand, and if it took me six hours or even more (it seems to me my pace could really slump dangerously), then I stayed in the chair till it was done. But it wasn't lonely, because I had Pierre and Andrei with me and all the others who lived in the felled forest of pages of War and Peace.

Biographer Ernest Simmons says "Tolstoy" means fat. Considering that W&P is 1200 pages, this reminds me of a mason I know who happens to be named Brickley.

View all my reviews

Published on February 18, 2011 08:36

Austin Ratner's Blog

Untimely thoughts on books both great and supposedly great.

- Austin Ratner's profile

- 32 followers

Austin Ratner isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.