Beth M. Howard's Blog, page 6

September 9, 2018

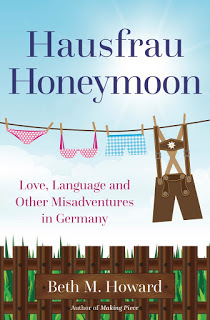

My Next Book, HAUSFRAU HONEYMOON, is Coming Soon

In June, after logging several months of marathon hours at my computer, I finished my manuscript for my American Gothic House memoir. (It really was like running a marathon!) I submitted it to a big-five publisher who had asked to see it, which in itself was a kind of thrill. But once I hit the send button, I looked around my office and asked myself, "Now what?"

In June, after logging several months of marathon hours at my computer, I finished my manuscript for my American Gothic House memoir. (It really was like running a marathon!) I submitted it to a big-five publisher who had asked to see it, which in itself was a kind of thrill. But once I hit the send button, I looked around my office and asked myself, "Now what?"I had read a few articles by other writers about what to do during the submission process, a period of waiting that can take several months. The answer was "Start your next book."

What? No! I was still tired from crossing the 350-page finish line and couldn't fathom starting that long journey again, and certainly not so soon. But then I remembered that I have another book -- one that's already written!

Hello, Hausfrau Honeymoon: Love, Language, and Other Misadventures.

I wrote this memoir 12 years ago, when Marcus and I were first married and living in Germany. Writing the book was my way of coping with the difficulties of adjusting, both to a new culture and to marriage. I still don't know which was harder! I had to learn the language. I had to learn new customs and rules. So. Many. Rules. I had to learn how to balance my previously independent life with supporting my husband in his career, as he was on track for a promotion. After he got his Golden Ticket, we would be free to choose another place to live where we could both be happy. So I thought. Instead, I signed up for more German classes, and the misadventures continued.

I printed out my old manuscript and read it again after not having looked at it for 10 years. I had fun turning the pages, laughing a little, wincing a little, crying a little, as I relived the experiences, the excitement, the frustrations, the determination, the love. It made me miss Marcus. It made me remember why I loved him. It even made me want to go back to Germany! (But just to visit.)

Given that I dusted this off to fill the time during the submission process, the thought of submitting this to a publisher only to endure another waiting period did not appeal to me. Which is why I decided to self-publish Hausfrau Honeymoon.

Here is what I've learned so far:

1. You will love having creative control.

I get to choose my own cover, choose my own interior font, decide on the styles for chapter headings and section breaks. I even get to choose the paper and the book's dimensions. I get to own the whole look and feel. This is important to me because a book is more than just the words. This book in its entirely represents me and my personal story. If you have a traditional publisher, you have to be really famous or a NYT-bestselling author to have any say in the creative process, and even then you have to have it spelled out in your contract.

2. The learning process is laborious but fun and fascinating.

I've spent hours and hours reading articles about self-publishing: the dos, the don'ts, the pros, the cons, the timelines, the checklists, the most common mistakes to avoid, which indie publishing companies to use, and more. There's a lot of information out there, and thanks to the Internet most of it is free. I highly recommend Jane Friedman's blog. (Her blog links to many other great resources.) If Hausfrau Honeymoon succeeds as a self-published title, I will have Jane to thank. (That said, I'm not even sure how I would define "succeeds." Selling 10,000? 100,000? Holding just one printed copy in my hand will be enough!)

3. You can't do this alone.

Having already been through the publishing process the traditional way, twice, I understand and appreciate just how much work goes into getting a book into print. Publishing houses have teams of people for each stage of a book: the editor, copy editor, proofreader, sales and marketing, designers, distributors, publicists, etc. When you self-publish, you will need each of these, and while you may have the superhuman powers to do all of these jobs yourself, you will want to hire some outside help. So far I've been working with a book designer and a copy editor -- and a slew of writer friends who are giving me feedback, guidance, and support.

4. Amazon isn't the only place to self-publish.

Where and how do you get your book out there? Again, I have Jane Friedman to thank for her advice. She suggests publishing in two places. One is Amazon, which covers all sales for Kindle ebooks and all print sales on Amazon only. Amazon is a closed system, much the way Apple's Mac and iPhones talk to each other but not to PCs or Androids, so you need to have a second supplier to cover book sales to the rest of the non-Amazon world. (Yes, a world beyond Amazon still exists!) Jane recommends IngramSpark to make your ebook available on Nook, Kobo, iBook, and all the other versions of ebook reader devices -- also so your print book can be distributed to book stores and libraries. (As you can imagine, Amazon would rather you didn't buy your books from other stores.) So I am using both Amazon and IngramSpark to give my book a bigger life -- and give you, the reader, broader access ensuring you will be able to find it in the vast and growing sea of indie titles.

5. You can save trees.

In traditional publishing, thousands of books are printed at once. When self-publishing, if you have the funds, the fan base, what have you, you can choose this option. Or you can have books printed on demand (POD). I like the idea of POD, creating books only on an as-needed basis. That means less paper wasted (more trees saved!) and no need for a warehouse or a garage (or in my case here on the farm, a grain bin) for storing books that may or may not ever get sold. I remember seeing a bookstore in New York City where they had a POD printer right in the store. I'd like to think we will see more of an in-store POD business model in the future.

6. You will be terrified. (I am anyway!)

The one thing I did not expect in this exciting, entrepreneurial endeavor is how terrified I would be to put my work out there. I have never been this scared to expose myself! By self-publishing I don't have an agent or publishing company to blame if my book doesn't sell, and I don't have them to hide behind when the criticism comes pouring in. And it will.

Hausfrau Honeymoon isn't exactly a love letter to Germany. This book likely won't be well received by Germans at all. They might not even let me back into their country! Out of the 10 readers I've had, half of them have loved it. The other half have given me notes that start off with "I don't want to offend you, but..." before launching into their one- or two-star reviews. But it's my story, my own personal and unique experience, my own perspective, and in spite of knowing the risks, I still have a desire to share it. To quote Sean Thomas Dougherty's poem: "Because right now, there is someone out there with a wound in the exact shape of your words."

When I tried to get Hausfrau Honeymoon published right after I wrote it 12 years ago, publishers said, "If it were about France or Italy, we would buy it. But Germany isn't romantic enough." I know! That is EXACTLY the point of my story! In fact, I could have made the title Why Couldn't I have Fallen in Love with a Frenchman or an Italian?

Germany may not be "romantic enough," but my book is full of romance. And though it probably won't make you want to move to Germany, you will learn a lot about the country, both the frustrating parts and the good parts. Hopefully the story will make you want to at least visit. As I said above, even after reliving the hard stuff, it had that effect on me. And if the ultimate outcome of my marriage to Marcus is already known to readers, I hope the story will still resonate as it is ultimately a love story about two people and their dogged determination to merge their disparate lives. Love may not conquer all, but there is nobility in the effort. I'd like to think that is worth something -- at least the $14.99 cover price.

Hausfrau Honeymoon: Love, Language, and Other Misadventures will be launched into the world on October 1st. I'll post ordering info as soon as it's available.

Published on September 09, 2018 12:01

August 29, 2018

The Day I Thought I Had Cancer

The night before my annual mammogram I was thinking about canceling my appointment. Did I want to be bothered with a trip to the hospital—50 minutes away—to have my boobs squished between two plates and hit with a dose of radiation? No. Did I have any history of breast cancer in my family? No. My mammogram last year was fine. So why go?

The commercials may be more

The commercials may be more

important than you know.Just as I was lamenting this to my boyfriend, Doug, who was listening to the Cardinals baseball game on the radio, a PSA came on. “About one in eight women will develop invasive breast cancer over the course of her lifetime,” it began. “If you are 40 or older, get a mammogram every year to avoid cancer—or death.”

Why was this airing during a major league baseball game? It didn’t seem like the right demographic for this. Or…was this message meant just for me? I took it as a sign and went to my appointment the next day.

Two days later I got a call from my doctor. “Your right breast shows no sign of malignancy,” she said, “but…”

But what? I suddenly realized this was not going to be a call to tell me everything looked normal.

“But there is a focal asymmetry on the left. We’ve scheduled an ultrasound for you for at one o’clock tomorrow.”

That they didn’t even ask if the appointment time worked for me made me think they considered my case urgent…as if it were a life—or death—emergency.

After we hung up I sprinted to Dr. Google to figure out what focal asymmetry meant. Did it mean…cancer? I learned that it could—and that was all it took for me to spend the next 24 hours considering the possibility of having The Big C, and all that a diagnosis might imply. A friend of mine had breast cancer and it spread. I went to her funeral a few months ago. (Read the story here.) So to say my imagination went wild would be an understatement.

First, I thought of all the reasons this (cancer) might have happened, and caused my cells to mutate:

Could it be from carrying my cell phone around in the front pocket of my bib overalls—right on top of my left breast?

Could it be from living on the farm, breathing in the pesticides?

Could it be from eating too much meat? (Said farm raises cattle and hogs.)

Could it be from The Great Hormonal Shift known as menopause?

Could it be from the increased stress I’ve had over the last year and a half, the combo of my dad dying (from cancer) and my dog Jack almost dying several times (from diabetes)?

Could it be Karma, that I should have treated people better, done more to help the homeless and the poor?

Next, I thought of all the people (and pets) who would outlive me—the ones I had expected to pass on years ahead of me. I thought of all the crap I would have to get rid of so it wouldn’t be left behind for someone else to deal with. I thought of the old journals I’ve been meaning to burn, the clothes I’ve been meaning to take to Goodwill, the piles on my desk I’ve been meaning to file.

I thought of the things I would do with whatever time I have left:

- Go on more bike rides.

- Eat whatever the hell I want! Especially ice cream.

- Take Doug to Africa on a safari, and to Italy to indulge in the food. (See above: eat whatever the hell I want!)

I thought of all the things I would miss:

- Swimming

- My dog, my goats, my boyfriend, my family

- Cocktail hour on the porch swing

- Feeling the wind in my face

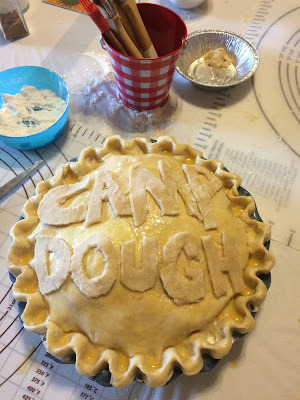

- Peach crumble pie

And all the things I would NOT miss:

- Mean, abusive people

- Guns and violence

- Divisive politics

- Toxic masculinity

- Seeing the demise of our planet

I thought of all the things I’m grateful for:

- Modern medicine and mammograms—and Obamacare

- The love of Doug, my family and friends, all my pets

- The privilege I was born into

- The education I’ve had

- The means to travel the world

- My health (up to now)

I thought of how I would tackle the cancer Angelia Jolie-style—aggressively, by cutting off both breasts. I thought of how I would look with a flat chest and of what I would wear when I no longer needed a bra. I thought of how my hair would grow back, maybe coarse, maybe all gray.

The following day as I drove to the hospital, I saw the familiar scenery in a different way. The sky, the clouds, the blackbirds on the fence posts, the red barns, the white dotted line on the highway, every single detail appeared more vivid, sharper, more meaningful, knowing I might not be on this beautiful earth much longer.

In the Diagnostic Imaging ward, I was ushered to a dark room, disrobed from the waist up, and lay on a bed while a technician moved her wand across my chest. She kept her eyes focused on the black and white monitor—and I kept my eyes focused on her, looking for any trace of concern, any hint of news.

“It’s inconclusive,” she said. “I need to show it to the doctor and see what he says.”

I waited on the table, half naked. To keep myself calm I did some yoga stretches and leg lifts, hoping there was no hidden camera.

When the technician came back, she said, “The doctor wants you to have another mammogram. I’ll walk you over there right now.” She handed me a hospital-issue top. “You don’t need to get dressed. Just put this on.”

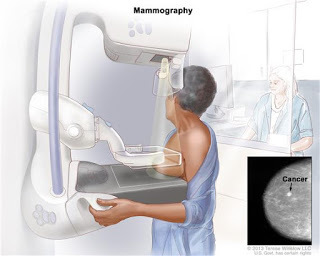

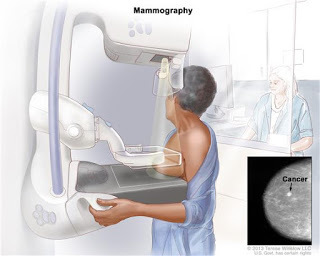

She ushered me into the mammogram room, the same room I had (begrudgingly) been in four days earlier. The technician was, as the others had been, friendly, speaking in gentle tones, and going about her business as usual, tasks that she and her coworkers do daily for hundreds, nay thousands, of other women: Placing sticker with a tiny metal ball on nipples. Positioning body and arms against X-ray machine. Giving instructions to hold breath. Pressing button to take picture.

This is what it's like, in case you've never seen what women go through to get tested.

This is what it's like, in case you've never seen what women go through to get tested.

She showed me the image, black and white and blurry and, to the untrained eye, hard to comprehend. She pointed out the fibrous tissue, the ducts, the adipose fat, the muscle—the unknown parts of me hidden under the skin.

“This is the area where the doctor saw the spot,” she said. “Where there was a change from last year’s image.”

It was no bigger than a pea. But a pea-size mass is still a mass.

While the doctor was summoned to analyze my mammogram, I sat in the waiting room—in my pink hospital top that didn’t stay closed because of the worn-out Velcro closures. The TV was tuned into a soap opera, “Days of Our Lives,” the one my sister had been on 25 years earlier. The drama was still the same, so were some of the actors, as I recognized a few. As for my sister, she had either been carted off to a mental institution or killed by an ex-lover, or…maybe she died from breast cancer—I don’t remember how her role ended, but seeing the soap made me think back on the last 25 years (actually, all 56 years of my life) and how I had packed a lot of experiences into those years. Maybe I had lived so fiercely because somewhere in my intuition I knew my time would be cut short. Nowadays, it seems like it’s not a matter of if you get cancer (or shot in a school or hit by a distracted driver), but when.

I waited. And waited. It wasn’t long in the scheme of hospital visits, but 20 minutes feels like 20 hours when you are waiting to hear if your life is going to be fine—or if it’s going to hell.

Finally, the technician came back out, took me into the dressing room, and shut the door. Here we go. Here comes the news. I braced myself.

“It’s nothing,” she said. “You have dense tissue so next time get a 3D mammogram. You won’t need to come back for another year.”

When I went outside into the sunlight, I had to blink to fend off the brightness—and the tears. “It’s nothing.” It was not cancer. I was fine.

Let's do away with these ribbons

Let's do away with these ribbons

and find a cure already!

I was fine, but as I walked out to the parking lot, passing other people walking in, I wondered about all the others who were not fine. The other women whose ultrasounds showed malignant tumors or whose mammograms sent them on to the next stage for a biopsy, and the many (too many) others who were at this moment tethered to chemo drips or confined to hospital beds or taking their last breaths as I walked out with my health—and my freedom.

I sat down by the outdoor fountain at the hospital entrance to collect myself. Relief washed over me like the water cascading down the fountain’s pyramid of gold shingles. And then came the tears, the release of the terror I had been harboring for 24 hours. Soothed by the moving water, I took a few minutes to transition from “this might be the end” to “life goes on.”

In our house we have an expression we have been using since my dog was diagnosed with diabetes last year. “Every day is a bonus,” we say. As we ride the waves of my dog’s good days and bad days, Doug and I remind each other that every day he is still with us is a bonus. As a 56-year-old woman who has had a lifetime of good health, I've had no reason for counting each day as a bonus for myself. It even seemed a bit paranoid, fatalistic to count the days that way. But this “little scare” is a reminder of just how quickly things could change.

In a way, I’m glad I went through this as it forced me to consider what’s important to me, and reminded me not to put things off. I now have a list of Things I’d Miss and Things I Want to Do Before I Die that I can consult for those times I relapse into taking life for granted.

Me. Celebrating. Life.With my list in mind, I left the hospital and drove—with my windows down—straight to Dairy Queen. I went home and hugged my dog and my goats, went for a swim, and joined my boyfriend for a gin and tonic on the porch swing.

Me. Celebrating. Life.With my list in mind, I left the hospital and drove—with my windows down—straight to Dairy Queen. I went home and hugged my dog and my goats, went for a swim, and joined my boyfriend for a gin and tonic on the porch swing.

I also put a reminder on my calendar to schedule next year’s mammogram. And guaranteed, when that day comes around, it won’t take a Cardinals baseball game to convince me to keep the appointment. ⧫

Some breast cancer resources:

https://ww5.komen.org

https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org

https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/m...

Well, what are you waiting for? Go get your mammogram screening. Do it.

The commercials may be more

The commercials may be moreimportant than you know.Just as I was lamenting this to my boyfriend, Doug, who was listening to the Cardinals baseball game on the radio, a PSA came on. “About one in eight women will develop invasive breast cancer over the course of her lifetime,” it began. “If you are 40 or older, get a mammogram every year to avoid cancer—or death.”

Why was this airing during a major league baseball game? It didn’t seem like the right demographic for this. Or…was this message meant just for me? I took it as a sign and went to my appointment the next day.

Two days later I got a call from my doctor. “Your right breast shows no sign of malignancy,” she said, “but…”

But what? I suddenly realized this was not going to be a call to tell me everything looked normal.

“But there is a focal asymmetry on the left. We’ve scheduled an ultrasound for you for at one o’clock tomorrow.”

That they didn’t even ask if the appointment time worked for me made me think they considered my case urgent…as if it were a life—or death—emergency.

After we hung up I sprinted to Dr. Google to figure out what focal asymmetry meant. Did it mean…cancer? I learned that it could—and that was all it took for me to spend the next 24 hours considering the possibility of having The Big C, and all that a diagnosis might imply. A friend of mine had breast cancer and it spread. I went to her funeral a few months ago. (Read the story here.) So to say my imagination went wild would be an understatement.

First, I thought of all the reasons this (cancer) might have happened, and caused my cells to mutate:

Could it be from carrying my cell phone around in the front pocket of my bib overalls—right on top of my left breast?

Could it be from living on the farm, breathing in the pesticides?

Could it be from eating too much meat? (Said farm raises cattle and hogs.)

Could it be from The Great Hormonal Shift known as menopause?

Could it be from the increased stress I’ve had over the last year and a half, the combo of my dad dying (from cancer) and my dog Jack almost dying several times (from diabetes)?

Could it be Karma, that I should have treated people better, done more to help the homeless and the poor?

Next, I thought of all the people (and pets) who would outlive me—the ones I had expected to pass on years ahead of me. I thought of all the crap I would have to get rid of so it wouldn’t be left behind for someone else to deal with. I thought of the old journals I’ve been meaning to burn, the clothes I’ve been meaning to take to Goodwill, the piles on my desk I’ve been meaning to file.

I thought of the things I would do with whatever time I have left:

- Go on more bike rides.

- Eat whatever the hell I want! Especially ice cream.

- Take Doug to Africa on a safari, and to Italy to indulge in the food. (See above: eat whatever the hell I want!)

I thought of all the things I would miss:

- Swimming

- My dog, my goats, my boyfriend, my family

- Cocktail hour on the porch swing

- Feeling the wind in my face

- Peach crumble pie

And all the things I would NOT miss:

- Mean, abusive people

- Guns and violence

- Divisive politics

- Toxic masculinity

- Seeing the demise of our planet

I thought of all the things I’m grateful for:

- Modern medicine and mammograms—and Obamacare

- The love of Doug, my family and friends, all my pets

- The privilege I was born into

- The education I’ve had

- The means to travel the world

- My health (up to now)

I thought of how I would tackle the cancer Angelia Jolie-style—aggressively, by cutting off both breasts. I thought of how I would look with a flat chest and of what I would wear when I no longer needed a bra. I thought of how my hair would grow back, maybe coarse, maybe all gray.

The following day as I drove to the hospital, I saw the familiar scenery in a different way. The sky, the clouds, the blackbirds on the fence posts, the red barns, the white dotted line on the highway, every single detail appeared more vivid, sharper, more meaningful, knowing I might not be on this beautiful earth much longer.

In the Diagnostic Imaging ward, I was ushered to a dark room, disrobed from the waist up, and lay on a bed while a technician moved her wand across my chest. She kept her eyes focused on the black and white monitor—and I kept my eyes focused on her, looking for any trace of concern, any hint of news.

“It’s inconclusive,” she said. “I need to show it to the doctor and see what he says.”

I waited on the table, half naked. To keep myself calm I did some yoga stretches and leg lifts, hoping there was no hidden camera.

When the technician came back, she said, “The doctor wants you to have another mammogram. I’ll walk you over there right now.” She handed me a hospital-issue top. “You don’t need to get dressed. Just put this on.”

She ushered me into the mammogram room, the same room I had (begrudgingly) been in four days earlier. The technician was, as the others had been, friendly, speaking in gentle tones, and going about her business as usual, tasks that she and her coworkers do daily for hundreds, nay thousands, of other women: Placing sticker with a tiny metal ball on nipples. Positioning body and arms against X-ray machine. Giving instructions to hold breath. Pressing button to take picture.

This is what it's like, in case you've never seen what women go through to get tested.

This is what it's like, in case you've never seen what women go through to get tested. She showed me the image, black and white and blurry and, to the untrained eye, hard to comprehend. She pointed out the fibrous tissue, the ducts, the adipose fat, the muscle—the unknown parts of me hidden under the skin.

“This is the area where the doctor saw the spot,” she said. “Where there was a change from last year’s image.”

It was no bigger than a pea. But a pea-size mass is still a mass.

While the doctor was summoned to analyze my mammogram, I sat in the waiting room—in my pink hospital top that didn’t stay closed because of the worn-out Velcro closures. The TV was tuned into a soap opera, “Days of Our Lives,” the one my sister had been on 25 years earlier. The drama was still the same, so were some of the actors, as I recognized a few. As for my sister, she had either been carted off to a mental institution or killed by an ex-lover, or…maybe she died from breast cancer—I don’t remember how her role ended, but seeing the soap made me think back on the last 25 years (actually, all 56 years of my life) and how I had packed a lot of experiences into those years. Maybe I had lived so fiercely because somewhere in my intuition I knew my time would be cut short. Nowadays, it seems like it’s not a matter of if you get cancer (or shot in a school or hit by a distracted driver), but when.

I waited. And waited. It wasn’t long in the scheme of hospital visits, but 20 minutes feels like 20 hours when you are waiting to hear if your life is going to be fine—or if it’s going to hell.

Finally, the technician came back out, took me into the dressing room, and shut the door. Here we go. Here comes the news. I braced myself.

“It’s nothing,” she said. “You have dense tissue so next time get a 3D mammogram. You won’t need to come back for another year.”

When I went outside into the sunlight, I had to blink to fend off the brightness—and the tears. “It’s nothing.” It was not cancer. I was fine.

Let's do away with these ribbons

Let's do away with these ribbonsand find a cure already!

I was fine, but as I walked out to the parking lot, passing other people walking in, I wondered about all the others who were not fine. The other women whose ultrasounds showed malignant tumors or whose mammograms sent them on to the next stage for a biopsy, and the many (too many) others who were at this moment tethered to chemo drips or confined to hospital beds or taking their last breaths as I walked out with my health—and my freedom.

I sat down by the outdoor fountain at the hospital entrance to collect myself. Relief washed over me like the water cascading down the fountain’s pyramid of gold shingles. And then came the tears, the release of the terror I had been harboring for 24 hours. Soothed by the moving water, I took a few minutes to transition from “this might be the end” to “life goes on.”

In our house we have an expression we have been using since my dog was diagnosed with diabetes last year. “Every day is a bonus,” we say. As we ride the waves of my dog’s good days and bad days, Doug and I remind each other that every day he is still with us is a bonus. As a 56-year-old woman who has had a lifetime of good health, I've had no reason for counting each day as a bonus for myself. It even seemed a bit paranoid, fatalistic to count the days that way. But this “little scare” is a reminder of just how quickly things could change.

In a way, I’m glad I went through this as it forced me to consider what’s important to me, and reminded me not to put things off. I now have a list of Things I’d Miss and Things I Want to Do Before I Die that I can consult for those times I relapse into taking life for granted.

Me. Celebrating. Life.With my list in mind, I left the hospital and drove—with my windows down—straight to Dairy Queen. I went home and hugged my dog and my goats, went for a swim, and joined my boyfriend for a gin and tonic on the porch swing.

Me. Celebrating. Life.With my list in mind, I left the hospital and drove—with my windows down—straight to Dairy Queen. I went home and hugged my dog and my goats, went for a swim, and joined my boyfriend for a gin and tonic on the porch swing.I also put a reminder on my calendar to schedule next year’s mammogram. And guaranteed, when that day comes around, it won’t take a Cardinals baseball game to convince me to keep the appointment. ⧫

Some breast cancer resources:

https://ww5.komen.org

https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org

https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/m...

Well, what are you waiting for? Go get your mammogram screening. Do it.

Published on August 29, 2018 14:22

March 19, 2018

Could Today Get Any Better?

Today has been surreal. I woke up to discover that the story I wrote for the New York Times about living in the American Gothic House was placed on the front page of the Arts section.

Today has been surreal. I woke up to discover that the story I wrote for the New York Times about living in the American Gothic House was placed on the front page of the Arts section.Early this morning, a friend sent me a picture of the print version of the newspaper —since we don't get it delivered here on the farm. Taking up almost the entire page was a photo of me, dressed in overalls and braids, posing with a pitchfork in front of my beloved old house in Eldon, Iowa.

It was exciting enough to get a piece published at all in the mother of all newspapers, but to get a feature this big? Seriously, I am still in shock.

Read the article online here

Read the article online here The article is even bigger inside the section!But the day just got stranger. In a good way.

The article is even bigger inside the section!But the day just got stranger. In a good way.I had been putting off a trip to the grocery store for days now, until—NYT excitement or not—buying groceries was imperative. I had been so busy, ahem, self-promoting my story on social media all morning, I forgot to eat, so I stopped at McDonald’s on my way to the store. (Hey, it’s rural Iowa. It’s not like there are a lot of choices. Besides, I like their pancakes, plus they have lattes.)

I waited for the three people in front of me to order and then it was my turn.

“Do you still serve pancakes?” It was just before noon.

“Yes,” the counter person said.

Phew! Adding an all-day breakfast is the best decision McD's has ever made.

“Great. I’ll have the pancakes and a small latte, no flavor."

A petite, redheaded woman was standing next to me quite close, and as I reached for my money to pay she moved in even closer.

“I’ll get that,” she said.

I didn’t know what she meant. She was holding a receipt so I knew she had paid and was waiting for her order. As I dug into my wallet, she pushed her hand in front of me, handing a ten-dollar bill to the cashier.

I was so confused. What was going on? Why was she paying--for me?

“I’ve got this,” she repeated.

While she paid I just stood there, immobilized with disbelief for the second time today—and it wasn’t even noon!

We moved to the side to wait for our food. She looked straight ahead at the counter, not showing any further interest in me, nor in any desire for conversation.

“What made you buy my breakfast?” I finally asked.

“Just think of it as a random act of kindness,” she said. “Like paying it forward.”

I looked into her eyes for a moment, searching for the reason she had singled me out. There were other customers who looked like they needed a free meal more than I did. Surely, in Fort Madison, Iowa, she hadn’t read the New York Times, so I ruled that out. Did she recognize me as “the Pie Lady of Eldon?” Or had she read my recent blog posts about my despair with the world (as well as the recent loss of a friend to cancer) and bought me breakfast because she felt bad for me?

But she wasn’t going to say anymore or give me any specifics.

“I’m just so….” I started, choking back tears. “I’m so touched.”

She still didn’t say anything. She wasn’t asking anything of me. She just wanted to do something nice, and I needed to be nice in return by simply accepting her gesture without demanding an explanation. Making a bigger fuss was only going to make her--make both of us--uncomfortable.

“Thank you,” I said. “I will just accept your gift graciously.”

The lump in my throat was so big it took me another minute before I could speak again. “I write about kindness in my blog,” I said, wiping my tears. “I’m going to write about you.”

She smiled shyly, but didn't say anything.

After another awkward pause, I added, “Funny enough, I was just thinking about that paying it forward idea on my way here. A friend of mine just did a huge favor for me and there is no way I can do enough to repay her. So I was going to tell her that I would pay it forward.”

I did not tell her that the friend is a staff writer at the New York Times who was responsible for connecting me with the Arts editor—not just connecting me, but pitching my story to her, the story that was on the front page of today's Arts section!!!

“How are the pancakes here?” she asked, changing the subject. “I always get the Egg McMuffin.”

Man, she was not going to explain anything more!

“They’re good,” I said. “But I almost always get the Egg McMuffin.”

“I like the lattes, too” she continued, “but not with any flavoring. That makes them too sweet. No whipped cream either.”

“Same here,” I said. “I drink the iced lattes in the summer. I like those a lot.”

“I’ll have to try one,” she said.

“Sometimes they’re too milky, so ask for extra espresso. That’s what I do.”

The counter person handed her a brown sack—presumably containing an Egg McMuffin.

“Have a nice day,” she said as she left.

“You too. And thank you again.”

And that was it.

Breakfast with a view.

Breakfast with a view. McDonald's in Fort Madison, Iowa I took my tray and found a table by the window. I sat there looking down at my food -- tears landing on the plastic lid that covered the pancakes -- too emotional to eat.

This stuff isn’t supposed to happen to me. I’m the one who is always preaching about kindness, sharing, giving of yourself, building community, contributing something valuable to society, blah, blah, blah…you know how I go on about world peace (and world piece.) I expect to be the one to give, not to receive. And here, in the span of a few hours, I had received an overabundance of riches.

It was too much to handle.

I couldn’t stop crying. But the tears were not of grief or despair, or even tears of joy. They were tears of gratitude. Because today, surreal as it was, I was reminded —in newsprint and in pancakes— that I have so very much to be grateful for.

Never has a McDonald’s breakfast been so delicious.

Published on March 19, 2018 16:56

February 23, 2018

All it Takes is a Few Words, a Few Bites, and a Willingness to Try

As you can see, I am really focused on promoting peace, love and understanding these days. It's a reaction to all the political maneuvering going on, a lot of policies being changed that are resulting in putting lives at risk, all because some people (too many) live in fear of what they don't know, what they don't understand. Even sadder, they don't even try to understand. They want to build walls around our country, because they have already built walls around themselves.

I keep searching for ways to break through those walls, and the solution I keep coming back to is simply this: connect with others outside of our own culture and language. Connection can mean something as simple as trying to communicate, even if just with a few words. Trying each other’s food, even if just a few bites. Visiting each other’s countries and homes and workplaces. To stop living exclusively in our own comfort zones and be open to seeing that our way isn’t the only way.

I once dated a guy who wasn’t interested in trying new things. For 25 years he has had the same job, lived in the same house, and has eaten at the same restaurants. One of those restaurants is Thai, which is the closest he's come to visiting a foreign country. He's a tea drinker so when he took me to the restaurant I asked if he had ever tried Thai iced tea—tea with sweetened condensed milk. No. He didn’t want to. “Come on, it’s only $2,” I insisted. No. No thanks. He’s progressive and caring and supports immigration rights, but he’s just not that open. But openness is what is needed from each of us, as individuals, to really understand each other, and understanding is what we need in order to make progress toward global harmony. A passport would be good too.

I always remember some friends returning from their vacation in Rome, Italy. They were complaining that the sidewalks weren’t straight. WHAT?! Those sidewalks are one of the main reasons you go to Rome, to walk in the steps of ancient Romans on the very cobblestones they laid centuries ago! They also complained about the food. “We got so tired of eating Italian food and all that pasta that we were thrilled to find a McDonald’s at the train station.” WHAT?! I gained at least 10 pounds in a week after eating my way through Italy—oh, the cannelloni! The calzone! The prosciutto! The cappuccino! The gelato! I couldn’t get enough of it. I wish my friends—along with another certain Big Mac-obsessed individual—could open up their worldview and have more appreciation—more acceptance—for life outside of America. To vivere la differenza.

One of the reasons this is on my mind is because I’m not in the USA right now. I'm in Mexico.

Parked at the grocery store.Last night I was in a grocery store, standing in the coffee section, trying to read the labels and figure out what kind to buy. (I have a coffee pot in my casita.) A large man pushed his way into the section and I stepped back to make room for him. He was clearly on a mission. He was older, weathered from the sun, with gray hair and a jowled face and, from his skin tone, I figured he was Mexican. He was homing in on a brand called La Finca so I asked him in my bad Spanish if it was good. He answered me in broken English, with a French accent—so I started chatting with him in my bad French, and tried to help him find the La Finca espresso beans he was looking for.

Parked at the grocery store.Last night I was in a grocery store, standing in the coffee section, trying to read the labels and figure out what kind to buy. (I have a coffee pot in my casita.) A large man pushed his way into the section and I stepped back to make room for him. He was clearly on a mission. He was older, weathered from the sun, with gray hair and a jowled face and, from his skin tone, I figured he was Mexican. He was homing in on a brand called La Finca so I asked him in my bad Spanish if it was good. He answered me in broken English, with a French accent—so I started chatting with him in my bad French, and tried to help him find the La Finca espresso beans he was looking for.

Speaking of farms...I made my coffee in the morning—Café La Finca’s Europeo blend, grown in Chiapas—and I thought of the man in the grocery store. (I also thought of Doug, because La Finca means The Farm. How perfect is that!)

Speaking of farms...I made my coffee in the morning—Café La Finca’s Europeo blend, grown in Chiapas—and I thought of the man in the grocery store. (I also thought of Doug, because La Finca means The Farm. How perfect is that!)

In the afternoon, I finally left my casita for a break after a particularly productive day of writing (I’m making progress on my book!) and rode my rusty rented beach cruiser to the fruit stand a few blocks away.

As I looked around at the produce, not recognizing half the ripe and wrinkly-skinned stuff in there, I had a hard time figuring what to buy—and how to pay for it. (The conversion of dollars to pesos still confuses me.) Finally, when the woman at the cash register had a break in customers, I asked her some questions—in Spanish.

Do you have Oaxaca cheese? Can I buy a small amount, just enough for one person? I will buy it later—what time do you close? What are these juices? What is the white one? The green one? Which one is mango?

She had a slight but constant scowl on her face as I asked one pregunta after another. She was short and barrel chested with black hair that she had tried to dye orange (black hair isn’t easy to color!) and she was wearing a plaid apron or pinafore, I’m not sure which. But she was definitely someone whose bad side you didn’t want to be on.

When I finally paid for a bottle of fresh mango juice I thanked her for her patience with my terrible español. “I’m trying to learn,” I told her, “poquito a poquito.” Oh how I wish our American schools placed an importance on learning other languages, and starting from an early age like they do in Europe.

I smiled extra hard to emphasize my apology—and my embarrassment. And then—que milagro!—she smiled back and said, “Sí, poquito a poquito.”

Her smile melted my heart like butter left out in the Caribbean sun.

When I went outside to unlock my bike, a couple of gringos were walking in. In front was a white-haired woman with sunburnt cheeks as red and round as the tomatoes on display, and behind her was her husband. I recognized him! I blurted out—in French—“La Finca café était très bon.” The coffee was very good. My français is as limited as my español, but it didn’t matter because his face lit up in happy surprise.

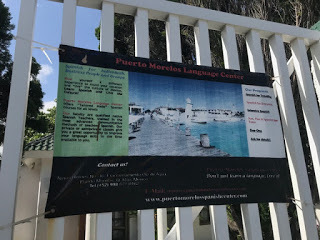

If I do come back for 2 months, I'll be in the classroom!He’s from Québec, he said, not France. And he comes to Mexico for two months every winter. (Which explains why his skin is as brown as a Mexican’s.) “I don’t want to go back to that cold weather,” he said.

If I do come back for 2 months, I'll be in the classroom!He’s from Québec, he said, not France. And he comes to Mexico for two months every winter. (Which explains why his skin is as brown as a Mexican’s.) “I don’t want to go back to that cold weather,” he said.

“I know! Same here. Next year I want to come back for two months,” I replied.

I finished unlocking my bike and as I tucked my mango juice and bike lock into the bike basket, he pointed to the rusty chain, thick with corrosion from the salty moist air, and asked, “Is that working okay for you?”

“Oui,” I said. “Ça va bien. And, anyway, I don’t mind, because I’m in Mexico, it's sunny, and I’m wearing flip-flops!”

As I pedaled away I waved and said, “Hasta luego!” See you soon. And if it keeps going like this, I probably will. (And, by the way, the fruit stand closes at 6:30 and I did go back for the cheese.)

My point is that all it takes is a little openness, a little courage and humility—okay, maybe more than a little. But who cares if you don’t know very many words and don’t even correctly pronounce the ones you do know? The fact that you even try is so appreciated. (Think of this the next time someone makes an effort to speak to you in English when it’s not their native language and commend them for their courage.) A few words can go a long way in making a connection and making someone smile. And a smile is the most basic, universal language of life, the first step across the bridge of understanding.

If we all just opened up a little to try to understand each other—to stumble over a few foreign words, to drink the Thai iced tea, to eat the fettuccine, to walk a mile in each other’s shoes—even if on crooked cobblestone sidewalks—the world could be a more peaceful, happier place.

I keep searching for ways to break through those walls, and the solution I keep coming back to is simply this: connect with others outside of our own culture and language. Connection can mean something as simple as trying to communicate, even if just with a few words. Trying each other’s food, even if just a few bites. Visiting each other’s countries and homes and workplaces. To stop living exclusively in our own comfort zones and be open to seeing that our way isn’t the only way.

I once dated a guy who wasn’t interested in trying new things. For 25 years he has had the same job, lived in the same house, and has eaten at the same restaurants. One of those restaurants is Thai, which is the closest he's come to visiting a foreign country. He's a tea drinker so when he took me to the restaurant I asked if he had ever tried Thai iced tea—tea with sweetened condensed milk. No. He didn’t want to. “Come on, it’s only $2,” I insisted. No. No thanks. He’s progressive and caring and supports immigration rights, but he’s just not that open. But openness is what is needed from each of us, as individuals, to really understand each other, and understanding is what we need in order to make progress toward global harmony. A passport would be good too.

I always remember some friends returning from their vacation in Rome, Italy. They were complaining that the sidewalks weren’t straight. WHAT?! Those sidewalks are one of the main reasons you go to Rome, to walk in the steps of ancient Romans on the very cobblestones they laid centuries ago! They also complained about the food. “We got so tired of eating Italian food and all that pasta that we were thrilled to find a McDonald’s at the train station.” WHAT?! I gained at least 10 pounds in a week after eating my way through Italy—oh, the cannelloni! The calzone! The prosciutto! The cappuccino! The gelato! I couldn’t get enough of it. I wish my friends—along with another certain Big Mac-obsessed individual—could open up their worldview and have more appreciation—more acceptance—for life outside of America. To vivere la differenza.

One of the reasons this is on my mind is because I’m not in the USA right now. I'm in Mexico.

Parked at the grocery store.Last night I was in a grocery store, standing in the coffee section, trying to read the labels and figure out what kind to buy. (I have a coffee pot in my casita.) A large man pushed his way into the section and I stepped back to make room for him. He was clearly on a mission. He was older, weathered from the sun, with gray hair and a jowled face and, from his skin tone, I figured he was Mexican. He was homing in on a brand called La Finca so I asked him in my bad Spanish if it was good. He answered me in broken English, with a French accent—so I started chatting with him in my bad French, and tried to help him find the La Finca espresso beans he was looking for.

Parked at the grocery store.Last night I was in a grocery store, standing in the coffee section, trying to read the labels and figure out what kind to buy. (I have a coffee pot in my casita.) A large man pushed his way into the section and I stepped back to make room for him. He was clearly on a mission. He was older, weathered from the sun, with gray hair and a jowled face and, from his skin tone, I figured he was Mexican. He was homing in on a brand called La Finca so I asked him in my bad Spanish if it was good. He answered me in broken English, with a French accent—so I started chatting with him in my bad French, and tried to help him find the La Finca espresso beans he was looking for. Speaking of farms...I made my coffee in the morning—Café La Finca’s Europeo blend, grown in Chiapas—and I thought of the man in the grocery store. (I also thought of Doug, because La Finca means The Farm. How perfect is that!)

Speaking of farms...I made my coffee in the morning—Café La Finca’s Europeo blend, grown in Chiapas—and I thought of the man in the grocery store. (I also thought of Doug, because La Finca means The Farm. How perfect is that!)In the afternoon, I finally left my casita for a break after a particularly productive day of writing (I’m making progress on my book!) and rode my rusty rented beach cruiser to the fruit stand a few blocks away.

As I looked around at the produce, not recognizing half the ripe and wrinkly-skinned stuff in there, I had a hard time figuring what to buy—and how to pay for it. (The conversion of dollars to pesos still confuses me.) Finally, when the woman at the cash register had a break in customers, I asked her some questions—in Spanish.

Do you have Oaxaca cheese? Can I buy a small amount, just enough for one person? I will buy it later—what time do you close? What are these juices? What is the white one? The green one? Which one is mango?

She had a slight but constant scowl on her face as I asked one pregunta after another. She was short and barrel chested with black hair that she had tried to dye orange (black hair isn’t easy to color!) and she was wearing a plaid apron or pinafore, I’m not sure which. But she was definitely someone whose bad side you didn’t want to be on.

When I finally paid for a bottle of fresh mango juice I thanked her for her patience with my terrible español. “I’m trying to learn,” I told her, “poquito a poquito.” Oh how I wish our American schools placed an importance on learning other languages, and starting from an early age like they do in Europe.

I smiled extra hard to emphasize my apology—and my embarrassment. And then—que milagro!—she smiled back and said, “Sí, poquito a poquito.”

Her smile melted my heart like butter left out in the Caribbean sun.

When I went outside to unlock my bike, a couple of gringos were walking in. In front was a white-haired woman with sunburnt cheeks as red and round as the tomatoes on display, and behind her was her husband. I recognized him! I blurted out—in French—“La Finca café était très bon.” The coffee was very good. My français is as limited as my español, but it didn’t matter because his face lit up in happy surprise.

If I do come back for 2 months, I'll be in the classroom!He’s from Québec, he said, not France. And he comes to Mexico for two months every winter. (Which explains why his skin is as brown as a Mexican’s.) “I don’t want to go back to that cold weather,” he said.

If I do come back for 2 months, I'll be in the classroom!He’s from Québec, he said, not France. And he comes to Mexico for two months every winter. (Which explains why his skin is as brown as a Mexican’s.) “I don’t want to go back to that cold weather,” he said.“I know! Same here. Next year I want to come back for two months,” I replied.

I finished unlocking my bike and as I tucked my mango juice and bike lock into the bike basket, he pointed to the rusty chain, thick with corrosion from the salty moist air, and asked, “Is that working okay for you?”

“Oui,” I said. “Ça va bien. And, anyway, I don’t mind, because I’m in Mexico, it's sunny, and I’m wearing flip-flops!”

As I pedaled away I waved and said, “Hasta luego!” See you soon. And if it keeps going like this, I probably will. (And, by the way, the fruit stand closes at 6:30 and I did go back for the cheese.)

My point is that all it takes is a little openness, a little courage and humility—okay, maybe more than a little. But who cares if you don’t know very many words and don’t even correctly pronounce the ones you do know? The fact that you even try is so appreciated. (Think of this the next time someone makes an effort to speak to you in English when it’s not their native language and commend them for their courage.) A few words can go a long way in making a connection and making someone smile. And a smile is the most basic, universal language of life, the first step across the bridge of understanding.

If we all just opened up a little to try to understand each other—to stumble over a few foreign words, to drink the Thai iced tea, to eat the fettuccine, to walk a mile in each other’s shoes—even if on crooked cobblestone sidewalks—the world could be a more peaceful, happier place.

Published on February 23, 2018 06:53

February 22, 2018

The World Needs More People Like Ann

My friend Ann is dying. She had breast cancer about 10 years ago but it came back. In her spine. Containable but not curable, the drugs held it back for about a year or two. I hadn’t talked to her for a while and last fall I had a very strong sense that I needed to get in touch—and not just by email. Something told me I needed to pick up the phone and call her. She was happy to hear from me, but had some not so happy news: The cancer was growing.

My friend Ann is dying. She had breast cancer about 10 years ago but it came back. In her spine. Containable but not curable, the drugs held it back for about a year or two. I hadn’t talked to her for a while and last fall I had a very strong sense that I needed to get in touch—and not just by email. Something told me I needed to pick up the phone and call her. She was happy to hear from me, but had some not so happy news: The cancer was growing.In early December, I started getting emails from Ann’s brother. I was on a mailing list, one I’m sure is a very big list because of the number of Ann’s friends. In the past several months the chemo was affecting Ann’s nerves to the point she could no longer use her hands or feet. She couldn’t write or walk. But there was the possibility, the hope, that the neuropathy could depart in the same quick way it began.

The updates kept coming.

Ann is being moved from the hospital to the rehabilitation center for physical therapy.

Ann is making progress and determined to get home.

Ann is going home, but will need 24-hour care. A nurse will be there during the day but we’ll have friends stay with her overnight, so let me know if you would like to come for a few days or a week.

I volunteered to spend a week with her in March. (She lives in San Francisco.) Given her loving friends I’m sure she has enough caregiving volunteers to get her through the next five years. But I will not be going to San Francisco to help because Ann won’t make it five years, or even five months.

I woke up to an email update from her brother.

Ann received news yesterday that her battle with cancer is quickly coming to an end. Ann has in mind to say her goodbyes in the coming days and weeks. Then it seems she will be ready to depart on her next adventure. She seems to have no regrets and accepts that this is her time. She has great care and love of those around her. And wishes you and us all great happiness, love and peace.

And so the grief begins.

Ann is just three years older than me. She has been a mentor, a role model, a big sister, a grief counselor after Marcus died, and a true and loving friend.

Like me, she lost someone she loved who died suddenly and unexpectedly, so she already knew the ropes of this kind of grief. (The cliché is intentional; her love was a rock climber.) She was there for me—to listen, to coach, to refill my wine glass, to just be. She was there for me a few years later when Daisy was killed by a coyote. Ann, a dog lover herself, was once again a step ahead of me as she had lost her dog Shayla (an Airedale terrier) not long before Daisy died.

Ann’s dog, Shayla, was one of the most remarkable dogs I’ve ever met. I tell the story of her often, how, when Ann worked from home, Shayla would come to Ann’s desk to remind her to get off the phone and take her for a walk. After a few minutes, if Ann was still talking, Shayla would go get her leash and present it to Ann, standing there with it dangling from her mouth which, with her tall size, was level with the desktop. And when that still didn’t work, she would go get Ann’s fleece jacket off the hook by the door and drop it onto Ann’s lap, signaling that, “Excuse me, you really need to hang up now. It’s time to go out.” If that cuteness couldn’t make you end a call, no matter how important the business discussion, nothing could!

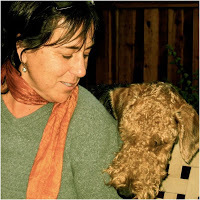

Ann and ShaylaShayla was only 7 when she died. She got sick and Ann did everything she could to keep her dog healthy, happy, alive. She even stayed with Shayla at the animal hospital, because she believed—she knew—her presence would help the dog recover. And, with Ann's affection, Shayla did recover (from an illness of leptospirosis.) Shayla's recovery, attributed to Ann's love, was so remarkable that a magazine did a story featuring Ann on how spending time at the vet with your sick pet helps it heal.

Ann and ShaylaShayla was only 7 when she died. She got sick and Ann did everything she could to keep her dog healthy, happy, alive. She even stayed with Shayla at the animal hospital, because she believed—she knew—her presence would help the dog recover. And, with Ann's affection, Shayla did recover (from an illness of leptospirosis.) Shayla's recovery, attributed to Ann's love, was so remarkable that a magazine did a story featuring Ann on how spending time at the vet with your sick pet helps it heal.I have followed Ann’s example of animal bedside care—many times now—whenever Jack is at the vet for his various health issues. (I did with Daisy, too.) Each time I sit on the cold cement floor of the vet's office, gently stroking my dog's fur for hours, I always think of Ann and Shayla and it keeps me going.

Ann talked with a pet psychic after Shayla died and the psychic told her Shayla was doing okay. When Daisy died, Ann gifted me a session with the psychic who told me Daisy was doing okay. (When your heart is THAT broken, any little bit of reassurance or affirmation is helpful.) It is one of the most heartfelt gifts I have ever received.

Lately I have been experiencing a period of turmoil—depression and despair over a combination of things: the current battlefield of politics, climate change, gun violence in schools and, more personally, what it means to be 55 and all the upheaval that goes with it: menopause; muffin top; loss of libido, bone density, and muscle tone; the seemingly limited future of my career; how to manage my finances; how to balance the solitude of the farm with my need for city; and the sobering reality that I now qualify for senior housing. But all of my worries seem so trivial now, my whiny first-world problems thrust into perspective by the news that Ann, who is not even 60, is preparing to take leave.

Now I am asking:

What really matters?

What do we leave behind?

What are we most proud of?

What did we accomplish?

Ann hasn't squandered away her time in the existential wasteland of turmoil and despair. She has been too busy, spending her life helping others as well as the environment. She has been:

Advocating for women in the outdoor industryServing on boards of environmental non-profitsMentoring teams of young people to help them grow in their careersOverseeing a foundation’s endowment allocating grants to wilderness conservation and outdoor educationBuilding public speaking careers for adventurers, enabling them to share their risk management lessons learned from Mt. Everest, El Capitan, Antarctica and beyond Organizing a film festival featuring the feats of extreme athletes who have triumphed over tragedyAnd, in her earlier career, producing music events

She has traveled the world, spending a lot of time in the mountains—in the Himalayas, in Yosemite, in Muir Woods.

She has nurtured friendships that span the globe, often hosting those friends in her home, their sleeping bags and backpacks turning her living room—an otherwise cozy and elegant sanctuary filled with Buddhist art and Tibetan prayer flags—into a climbers’ base camp. I have been one of those lucky friends, sleeping bag in tow, treated to her home cooked meals (my favorite being grilled tilapia with sautéed mushrooms and puréed cauliflower, and a bottle of Malbec) and waking up on her couch to a view of the Redwood forest, talking with Ann for hours over coffee.

And yet, when the time comes—and, sadly, it is coming too soon—what will Ann be remembered for most? Not for her grilled tilapia and comfy couch. Not for her career and for her many, many accomplishments. Not even for her recent, wholly deserved Outdoor Industry Lifetime Achievement Award. All of that is impressive and important, yes. But what she will be remembered for most is her kindness. Her generosity. Her humility. Her love. Her spirit, a spirit so bright and beautiful its light will keep shining long after her physical form can no longer contain it.

May we all be so lucky to be remembered that way.

May Ann's legacy serve as a guide for those of us still here, and for others yet to come. May we channel her examples of honesty and integrity, to make the world a better place for as long as we are here.

We will miss you, Ann, but know you will be there with all of that kindness, generosity, humility, and love when we see you on the other side. And we will all get there eventually. Thank you for being in my life and for all the goodness you have contributed—to me and to so many others. Wishing you peace on your new journey, my friend. I look forward to meeting up with you in the next one.

With all my love and deepest gratitude,

Beth

Published on February 22, 2018 10:38

February 17, 2018

"There is ALWAYS Hope, Bea."

There is ALWAYS hope, Bea.

He wrote this—with the word always in all caps—above a newspaper article he had circled in black ink.

He left the paper on the kitchen table knowing I would be down for my morning coffee well after he had left the house to feed hay to his cows, check on the pigs, and attend to his other daily chores.

I always like it when I see his circles of ink on the page. I like the anticipation of discovering what specific nugget of news he wants me to see—something about a new business in the next town, a profile on someone who is using their skills to help those less fortunate, a well-written obituary of someone who led an extraordinary life. I like that he is loyal to the newspaper, having it delivered, still reading it in print instead of online, even though the paper arrives a day late. I like that he is a thinking man, a feeling man, a caring man. He doesn’t outwardly express himself—stoicism is bred into his German genes—but this sharing of newspaper articles tells me he is thinking of me, that he cares for me, that he wants to help me even though he doesn’t know how.

The article he circled this time was in the opinion section, his favorite part of the paper, which he always reads first, before the front page, before the commodity trading prices and weather, before the sports scores. The article was about South and North Korea uniting for the Winter Olympics in Seoul, a rare olive branch extended after 50 years of fighting and a war that cleaved a manmade fault line between two halves of a whole peninsula. After all this time—and all the recent escalating threats of nuclear action—a previously unimaginable union is taking place with both sides walking and competing together under one flag. Even if just for the 16 days of this one event, it signals the possibility of peace, a sign of hope.

There is ALWAYS hope, Bea.

He alone knows the depths of my sadness, the full picture of who I am and how much I struggle to stay balanced, to stay happy, to stay alive. The fun-loving girl in overalls and braids who basks in the country life of apple pies and goats and dog walks through green pastures—this is my curated life in colorful pictures on Facebook, the carefully edited version, the one that gives people a one-sided impression. The wrong impression. Fake news. Yes, I do smile and laugh and make people happy with my homemade pies, but many of my days—too many lately—are filled with despair, weighed down by a lead blanket of Weltschmerz (the German word for internalizing all the pain of the world.) Espresso and my dog’s insulin schedule are my only motivation to get out of bed in the morning, because I wake up tired after sleepless nights, my eyes wide open in the darkness as I pass the hours searching for answers, for meaning, for purpose, for hope. For solutions for how I can save the world.

He is the sole witness to both sides of my Yin and Yang, a black and white circle of life that has become lopsided and leaning too much on the black. He sees my grief—the cumulating losses of my husband, my dad, and even one of my goats—still as raw and festering as an infected stab wound. He listens as I unleash my rage over the state of the world, wailing about the injustices, the unending human rights violations, the suppression of women, the righteousness of the ultra-religious. He remains patient and quiet as I carry on, ranting about the increase of gun violence, the divisiveness of politics, the demolition of our democratic society, the proliferation of hate speech, the dismantling of health care, education and immigration, and the utter lack of respect for the environment and its finite resources. My list of wrongs I want to right is so very long. He leans against the counter, or the wall, or his pillow, biting the inside of his lip, as I cry and tell him yet again how I have lost my faith in humanity, how my heart—already so badly broken—cannot take anymore of this assault and battery. He is at a loss for words, or maybe he has nothing to say. He doesn’t know how to fix this. To fix me.

And then I come downstairs for coffee and see the newspaper splayed open on the table, his pen lying next to it, the familiar scribble of his handwriting.

There is ALWAYS hope, Bea.

I saved the newspaper page. I’ve been carrying it with me for a week. I pull it out of my notebook several times a day and read his sentence, spelled out in his scratchy handwriting, even though I no longer have to read it as the sentence is ingrained in my head. I hear it, the words repeating so often they’ve become the refrain of my personal anthem. And still, each time the sentence forms— punctuated at the end with his nickname for me—my throat tightens. My heart seizes up so hard I feel a rush of hot blood. And my eyes fill up so quickly with tears that I can’t hold them back, the drops leaving water stains on my notebook.

There is ALWAYS hope, Bea.

I am in Mexico this week for a writers’ retreat. I brought the article with me, folded neatly and tucked into my carry-on. I came with two goals: finish my American Gothic House memoir and get a break from the deep freeze of Iowa’s winter (and not necessarily in that order!) I have added one more thing to that list: find hope.

How does one find hope? How can I restore my faith in a humanity that keeps letting me down with its inability—its outright refusal—to get along? Is hope something you can hunt for? Something you can see? Is it tangible? And if you find it, how do you make it last?

My first day here I was walking on the beach, my bare feet splashing through the waves, the sun de-icing my body. I looked up from the sand toward the palm trees and houses and saw a boulder painted with graffiti. The art wasn’t that big, maybe not even noticeable to others, yet my eyes were drawn straight to it. On the rock was a white background with a child’s face outlined in black. Next to the child, painted in red ink, was one word: Hope.

There is ALWAYS hope, Bea.

It had to be a message, a sign.

I didn’t start actively looking for signs of hope. The first days I was still consumed with the stresses of my life back home, of all that I had abandoned in the name of self-care, still carrying the excess baggage of guilt over leaving Doug to take on my responsibilities—of giving Jack his medicine and hauling warm water to the goats. But with each day I spend in Mexico, thoughts of home—along with my Doomsday Clock-watching worries—slough off like the layers of my dry skin, making room for me to take in my new surroundings. With each day my observations of the life around me become more vivid, more frequent, more obvious—observations I’ve begun translating with the same hunger I hunt for words in my Spanish dictionary.

What I am observing, experiencing, finding is esperanza. Hope.

Hope is the gruff fruit vendor who made me wait while he rigged up his grandson’s fishing pole, tying a plastic bag on the end of it and putting a piece of pineapple inside as bait, and the four-year-old, so adorable with his freckles, curly hair and round cheeks, saying, “Gracias, Abuelito.” And how the other customers cheered on the child’s efforts to catch something, his arm—still chubby with baby fat—not yet strong enough to cast the line. And how the grandfather prepared the coconut meat for me after I drank the water from the shell, taking pride in serving it the local way, with salt and pepper, lime, and chili sauce. And how he smiled so warmly when I said, “Gracias, Abuelito.”

Hope is hiking on the trail through the jungle to get to the quieter beach and just as you’re wondering if it’s safe to do this alone, and realizing you haven’t told anyone where you’re going, a Mexican man jogs up the path, dripping with sweat from his workout, and as he passes you he pauses for a second, hands you a tiny sea shell, and says, “For you,” and then keeps going.

Hope is walking to the local espresso bar in the mornings, passing the kids on their way to school, so young and innocent—and sleepy—at 7:30am, dressed in clean clothes, hauling backpacks full of schoolbooks. And reading the outer wall of their school that spans a full block, covered in a hand-painted mural with messages of tolerance, cooperation, honesty, solidarity, and yes, hope. And the satisfaction of understanding enough Spanish to know that “En esta escuela trabajamos con amor” means “In this school we work with love.”

Hope is the shopkeepers sweeping and scrubbing their sidewalks, splashing buckets of water on the steps to make their storefronts look cleaner and more inviting, even when the effect is short-lived in a town with dirt roads.

Hope is eavesdropping on a conversation where a gray-haired expat in an embroidered Mexican dress relays her wisdom to a friend about the value of making decisions with her heart and not her head. (I wanted to butt in and tell her she should run for congress!)

Hope is the regular exchange of smiles and greetings of “Buenos dias” when passing strangers on the streets, whether their skin is brown, white, leathery, or sunburned.

Hope is the bougainvillea blooming with vitality in shades of magenta and orange and purple. It’s the breakfast of fresh papaya picked right off the tree. The morning swim in the sea. The baptism of diving under the waves and tasting the salt on your lips.

Hope is the sun coming up again and again and again, bringing with it the promise that there is still goodness in this world.

Hope is taking a much-needed break from home knowing there is a thinking, feeling, caring man waiting for me back on the farm. And though I love his ink-circled articles and his notes that go with them, I have found that hope is a lot easier to have when you don’t read the newspaper.

He wrote this—with the word always in all caps—above a newspaper article he had circled in black ink.

He left the paper on the kitchen table knowing I would be down for my morning coffee well after he had left the house to feed hay to his cows, check on the pigs, and attend to his other daily chores.

I always like it when I see his circles of ink on the page. I like the anticipation of discovering what specific nugget of news he wants me to see—something about a new business in the next town, a profile on someone who is using their skills to help those less fortunate, a well-written obituary of someone who led an extraordinary life. I like that he is loyal to the newspaper, having it delivered, still reading it in print instead of online, even though the paper arrives a day late. I like that he is a thinking man, a feeling man, a caring man. He doesn’t outwardly express himself—stoicism is bred into his German genes—but this sharing of newspaper articles tells me he is thinking of me, that he cares for me, that he wants to help me even though he doesn’t know how.

The article he circled this time was in the opinion section, his favorite part of the paper, which he always reads first, before the front page, before the commodity trading prices and weather, before the sports scores. The article was about South and North Korea uniting for the Winter Olympics in Seoul, a rare olive branch extended after 50 years of fighting and a war that cleaved a manmade fault line between two halves of a whole peninsula. After all this time—and all the recent escalating threats of nuclear action—a previously unimaginable union is taking place with both sides walking and competing together under one flag. Even if just for the 16 days of this one event, it signals the possibility of peace, a sign of hope.

There is ALWAYS hope, Bea.

He alone knows the depths of my sadness, the full picture of who I am and how much I struggle to stay balanced, to stay happy, to stay alive. The fun-loving girl in overalls and braids who basks in the country life of apple pies and goats and dog walks through green pastures—this is my curated life in colorful pictures on Facebook, the carefully edited version, the one that gives people a one-sided impression. The wrong impression. Fake news. Yes, I do smile and laugh and make people happy with my homemade pies, but many of my days—too many lately—are filled with despair, weighed down by a lead blanket of Weltschmerz (the German word for internalizing all the pain of the world.) Espresso and my dog’s insulin schedule are my only motivation to get out of bed in the morning, because I wake up tired after sleepless nights, my eyes wide open in the darkness as I pass the hours searching for answers, for meaning, for purpose, for hope. For solutions for how I can save the world.

He is the sole witness to both sides of my Yin and Yang, a black and white circle of life that has become lopsided and leaning too much on the black. He sees my grief—the cumulating losses of my husband, my dad, and even one of my goats—still as raw and festering as an infected stab wound. He listens as I unleash my rage over the state of the world, wailing about the injustices, the unending human rights violations, the suppression of women, the righteousness of the ultra-religious. He remains patient and quiet as I carry on, ranting about the increase of gun violence, the divisiveness of politics, the demolition of our democratic society, the proliferation of hate speech, the dismantling of health care, education and immigration, and the utter lack of respect for the environment and its finite resources. My list of wrongs I want to right is so very long. He leans against the counter, or the wall, or his pillow, biting the inside of his lip, as I cry and tell him yet again how I have lost my faith in humanity, how my heart—already so badly broken—cannot take anymore of this assault and battery. He is at a loss for words, or maybe he has nothing to say. He doesn’t know how to fix this. To fix me.

And then I come downstairs for coffee and see the newspaper splayed open on the table, his pen lying next to it, the familiar scribble of his handwriting.

There is ALWAYS hope, Bea.

I saved the newspaper page. I’ve been carrying it with me for a week. I pull it out of my notebook several times a day and read his sentence, spelled out in his scratchy handwriting, even though I no longer have to read it as the sentence is ingrained in my head. I hear it, the words repeating so often they’ve become the refrain of my personal anthem. And still, each time the sentence forms— punctuated at the end with his nickname for me—my throat tightens. My heart seizes up so hard I feel a rush of hot blood. And my eyes fill up so quickly with tears that I can’t hold them back, the drops leaving water stains on my notebook.

There is ALWAYS hope, Bea.

I am in Mexico this week for a writers’ retreat. I brought the article with me, folded neatly and tucked into my carry-on. I came with two goals: finish my American Gothic House memoir and get a break from the deep freeze of Iowa’s winter (and not necessarily in that order!) I have added one more thing to that list: find hope.

How does one find hope? How can I restore my faith in a humanity that keeps letting me down with its inability—its outright refusal—to get along? Is hope something you can hunt for? Something you can see? Is it tangible? And if you find it, how do you make it last?

My first day here I was walking on the beach, my bare feet splashing through the waves, the sun de-icing my body. I looked up from the sand toward the palm trees and houses and saw a boulder painted with graffiti. The art wasn’t that big, maybe not even noticeable to others, yet my eyes were drawn straight to it. On the rock was a white background with a child’s face outlined in black. Next to the child, painted in red ink, was one word: Hope.

There is ALWAYS hope, Bea.

It had to be a message, a sign.

I didn’t start actively looking for signs of hope. The first days I was still consumed with the stresses of my life back home, of all that I had abandoned in the name of self-care, still carrying the excess baggage of guilt over leaving Doug to take on my responsibilities—of giving Jack his medicine and hauling warm water to the goats. But with each day I spend in Mexico, thoughts of home—along with my Doomsday Clock-watching worries—slough off like the layers of my dry skin, making room for me to take in my new surroundings. With each day my observations of the life around me become more vivid, more frequent, more obvious—observations I’ve begun translating with the same hunger I hunt for words in my Spanish dictionary.

What I am observing, experiencing, finding is esperanza. Hope.