Maria Nazos's Blog, page 3

July 17, 2021

How Do I Deal with Procrastination? Let Me Count the Ways I Procrastinate AND Push Through

Do you experience that inner yelp of resistance each time you sit down to write? What about when you wrap up a big, huge submission for a big, huge contest? My inner saboteur has this shit down to a science. After years of observing my writing patterns, I know what my saboteur is and when it will arise.

I’ll sit down to submit something. BAM – an hour later, my house has never been cleaner. My laundry's done. I’ve managed to text every friend I’ve made since the Obama administration. Still, the application, the fellowship, or the submission has magically gone untouched.

I’m BRILLIANT at blocking my creativity and projects, especially if I don’t have to be accountable. No matter, we can devise ways to understand and work with the demons of procrastination.

Here’s how I handle writerly self-sabotage:

1) Know thyself

Your saboteur isn’t that creative. After a while, it will exhaust itself and revert to the same strategies. As I’ve told you, my procrastination usually creeps up in the form of pressing to-do items. There’s mold on that patio chair? Clean it up. Did someone text? How are they doing? My desk is dirty; give it a wipe-down.

Two hours later, I’m scrubbing away.

What forms does your saboteur take? Become acquainted with and befriend those tendencies. I even made a joke out of my self-sabotage. For instance, in the middle of an NEA application (if you’ve ever filled one out, you’ll understand), I began texting a friend. Mid-text, I stopped and said, “You know, this is what I do when I want to fuck myself over.” She texted back, “I won’t enable you,” with a heart emoji and a GIF of a tumbleweed.

2) Say WHEN

Whenever I draw close to finishing a hefty project, I’ll devise a billion side-projects. I’ll fixate on minute details. Oh, and this is a BIG ONE – just when I get to the part of an application where I have to ask for recommenders, I shut the fuck down.

Two hours later, I’ll look up and my reflection is gleaming back at me from a newly polished mirror. Now, whenever that moment happens, I tell myself, “This behavior is normal; this is what happens. You’re feeling REALLY uncomfortable, but that isn’t the worst thing. People endure bigger struggles every day.”

Then, I take a deep breath while my inner saboteur yelps in resistance. And before I can think too much, I hit “send.”

3) Confront the ego

When you think of the ego, do you usually think of an overinflated sense of self? Me, too. The ego, however, has another big job to do, and not an entirely useless one.

Your ego’s job is to keep you alive. One of the ways it keeps you safe is by pressing the panic button any time you push out of your comfort zone. So, when you sit down to submit to a competitive journal, your ego screams, “ABORT, ABORT, ABORT!” Why?

The possibility of success registers as unfamiliar and threatening. All your poor little ego knows is to keep you fed, safe, and sheltered. And it’s going to fuck with you until the bitter end to keep you safe.

Pay attention to that feeling; it’s a subtle one. For example, when I sat down to write and feel that subterranean impulse to run, then the strange comfort at the idea of surrendering to the fear, one day, my inner prize-fighter kicked in.

I told myself, “Hey, I know that your intentions are good, and you’re trying to keep me safe, but I know better. And I’m following through.”

That said, this self-talk is easier said than done. Talking back to your ego can be one of the most excruciatingly painful things you ever do. You’re working against your basic human survival impulses, which is a motherfucker. Although this battle never gets easier; it becomes familiar.

4) Soften the Saboteur

Although I still struggle, one of the most effective ways to tame my ego is to soften it. The way I see it, the ego is rooted in fear. Therefore, if you can focus on the positive outcomes of either the situation at hand or anything promising in your life, you can stave back self-destruction and eliminate the fear.

For example, I’m procrastinating right now as we speak.

Even as I type this blog, my chest is locking up. A little voice inside me is saying, “Why the fuck are you writing this post? Who gives a damn? Who will listen?”

But even so, I focus on the positive outcomes. I say to myself and you:

“Look, I know you’re scared but that’s because this feeling is unfamiliar. You’re still new to marketing yourself and your work. Here’s the deal, though: once you get through this [fellowship application, blog post, submission], think about all the wonderful outcomes. You’re creating AWARENESS of what you do.

You’re staying on people’s radars. You’re lingering in other people’s consciousness, even if they DO think this is the dumbest fucking blog post they’ve ever read. Don’t you want to be relevant? Don’t you WANT to be heard? Don’t you want to remain at the forefront of publishers’ consciousness? Well, get it done!”

So, what are you waiting for?

May 17, 2021

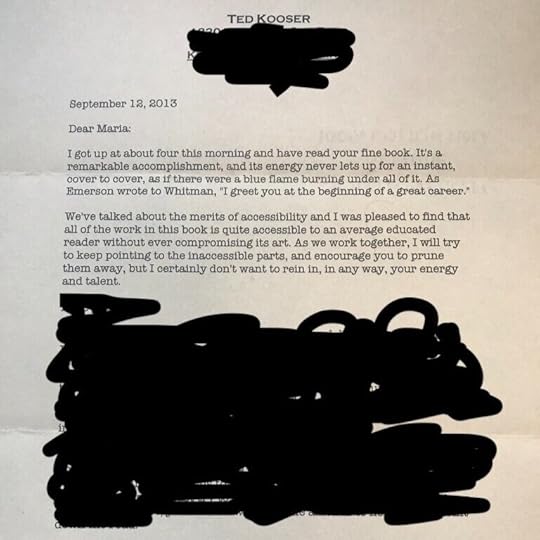

Formal Poetry is a Kitty on a Leash

When I first purchased a leash and harness for my cat, Olive, I was ecstatic. So many times, she’s sat on the window sill and stared longingly at squirrels, mouth agape, inhaling lusted-after outdoor scents. I harnessed her up like a little S&M junkie, tickled by the thought that I could give her the gift of freedom.

I’d conveniently forgotten that you can’t make a cat do anything; that includes enjoying the outdoors that she’s seemingly longed for, ever since she was a kitten. Still, I tried to drag her around the yard by her leash, to no avail. She’d go completely limp on the ground and refuse to budge. She’d hiss at other cats. She’d scream and whine when I tied her to a post because she’d managed to wrap herself around an oak tree.

Nonetheless, I persisted. When I tried to take her to the playground, she let out a scream that could curdle a corpse’s blood. Still, I’d tug on the leash, muttering under my breath, “Dammit, Olive, WE ARE HAVING FUN AND WALKING.”

What does this have to do with formal poetry?

It turns out, plenty. Much like harnessing and leashing a domestic cat, putting your poetry into a contained form can be a true pain-in-the-ass. There’s often neither payoff nor cooperation throughout the first 100 million times you try.

Similar to my insolent cat, poems have minds of their own. You can’t tease out a sestina without knowing the properties or how to bribe the form. On the other hand, once you learn the different formal vehicles, after failures and possibly scratch marks, just as soon as you’ve given up? BAM! The form yields to the content.

Eventually, I lured Olive outside with treats and catnip. I provided her the illusion of autonomy, allowing her to walk in and out of the house on her own with the leash trailing her. Thereafter, I bought more leashes and bound them together, so eventually, she could stray as far as the sidewalk. Just when she’d fallen in love with the yard, I untied her from her post and took her on a walk.

For a while, everything was great. She meandered through the yew bushes, sniffed the compost, and let out an occasional meow of delight. Then, without warning, she jerked herself against the leash so hard that I almost fell over. Then, she did it again, which just about face-planted me on the lawn.

Before I could register what was happening, she’d bucked out of her harness and taken off running across the lawn. As I ran after her, she turned and looked at me as if to say, “You THINK that I couldn’t have gotten away this whole time? You THINK you’re fooling me with this illusion of freedom? Fuck you. I AM in control.”

Like a domestic cat you’ve harnessed, the poem knows better than you. At a certain point, it either WILL conform to your expectations or NOT.

That is the dance we do when writing poetry. Sometimes, our poems will yield to us and, with the right finessing, we master the balance of surrender and control. Other times, our work will escape against our will – the whole time, it always knew better, and it can always get away.

So, trust that the poem has its own fits of hunger and desires. If your work wants to break into and out of a contained form, then let it, if only for a little while. Don’t be mad. Bring the poem home to you, accept that the process is hardly ever yielding. Meanwhile, as you try and fail to reign your poems in, you’ll occasionally reach mutual respect– and that is where the magic happens.

April 17, 2021

How Do a Rubber Chicken Purse, Audre Lorde, Ted Kooser, and a Stress Ball Inspire Me?

1. Me with my trusty chicken purse. 1) Everyone needs one. Do not argue with me. 2) This accessory reminds me never to take myself too seriously. But on a more serious note, this silly artifact reminds me to remain true to my silly, playful, messy self rather than trying to emulate some preconception of what a professional poet “should look like.”

My rule of thumb: never take myself too seriously. Remain true to my messiness.

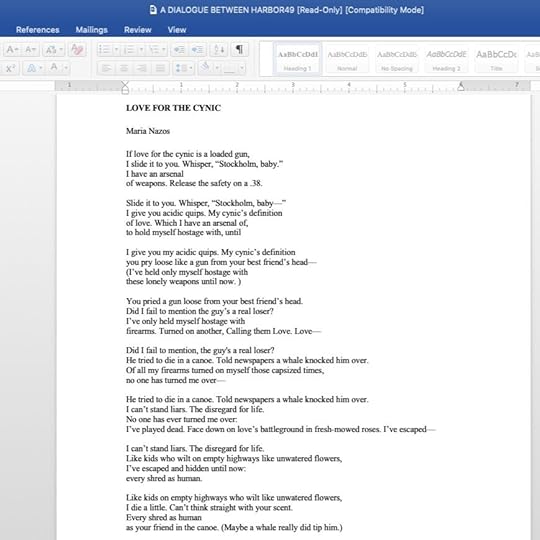

2. Before-and-after images of a poem. The Word doc is the original, failed draft from 8 years ago. The published one is the result of that failure! This poem is a reminder of the many iterations and resiliency it takes to write a good poem – and the work is never done. PS: The crap you write today might be The New Yorker poem you publish tomorrow – you never know.

The crap you write today could be The New Yorker poem you publish tomorrow!

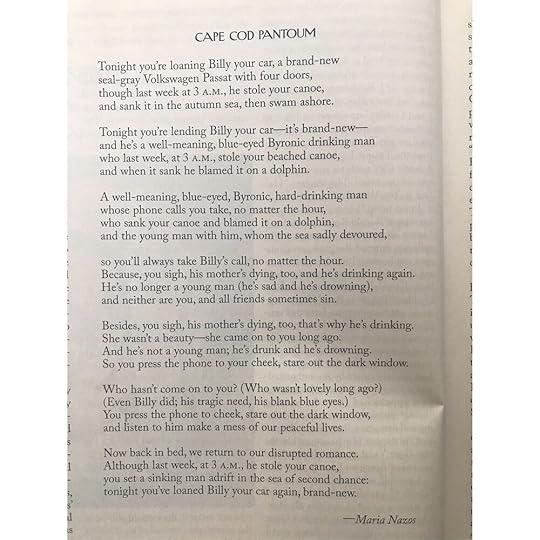

3. Audre Lorde painting – a reminder that remaining silent will neither keep me safe nor do I want it to stay silent. So, I ask myself, what is it about the work that makes me REFUSE to remain silent? The point of all art, whether it’s Dadaism or Expressionist, or narrative, is to communicate. If you ever work with me, one phrase you’ll hear me repeat is, “What is the emotional impulse of this poem, story, painting? Why couldn’t the speaker remain silent?”

Molly Crapapple’s painting of acclaimed Black, queer feminist, activist, and womanist, Audre Lorde, reminds me to NEVER remain silent.

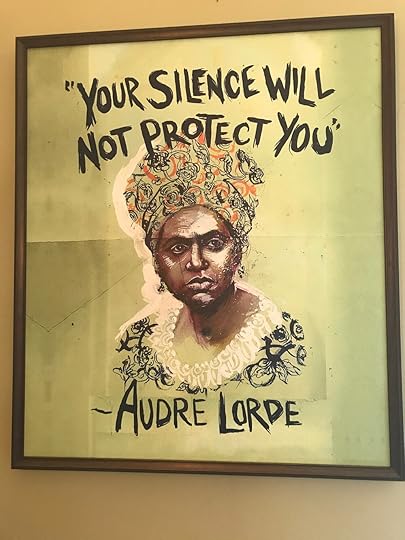

4. Letter from Ted Kooser – the letter helps me balance compassion, confidence, and truth throughout my work. Ted gave me a huge vote of confidence, but he also warned me about over-exposing certain family truths, including alcoholism, that hurt other people. I neither agree nor disagree with this letter or how much versus how little we ought to reveal. Rather, I keep this letter above my desk in order to remind myself of the delicate balance between honesty and compassion for my subjects.

Mixed praise and wisdom from former U.S. Poet Laureate and my honorary friend, mentor, and Grampa, Ted Kooser.

5. Me with a stress-ball: it keeps me sane and in my body during meetings (which I ABHOR). But more importantly, this little ball reminds me not to cling too tightly to my dreams and motivations. I have to forgo my rigid vision of what poetic success “should look like.” Instead, this little ball reminds me that success and work are malleable: Don’t hold on too tight. Remain open to gut-level nudges. The way things unfold and the channels through which they occur are never the way I expect. That is a good thing.

This yellow ball reminds me - DON’T squish your dreams into a rigid mold.

6. Picture of me with Ted Kooser – he’s been one of the great mentors of my career. Any time I’m discouraged, I’ll reach out to him, and he’ll infuse me with a powerful reminder: Do you want to be a Poet, or do you want to write poetry? His wisdom remains with me every day.

Me and Ted Kooser (right), who serves as a reminder - I am a poet, NOT a Poet.

March 13, 2021

40-Year-Old Version: Some Thoughts & Goals

Thank you for the birthday wishes! I was initially planning on doing a big spread on Sunday. I intended to gussy up, strike a badass pose, and create a cute caption.

Then, I realized that if I did, I'd be lying to myself and you. I awoke to feel dread, not about growing old, but about inching closer to death. I tried to shake the feeling, but like a concrete mantle, it hung over me.

As someone who wants to be authentic, I won't lie then, and I won't lie now. What I will say is, a few weeks later, I'm indebted to all of you who comment on my posts, poems, and journey, and allow me to witness yours.

My friend, Dr. Bill Berry, in particular, was a life-saver on my 40th birthday. As I took a walk through my neighborhood, I called him and reflected.

At this juncture in my life, I've assumed responsibility for my good and bad choices. We’re all at least half the product of our decisions. But that isn't always the case. The world isn't always hospitable, especially when beloved, kind, and healthy people struggle, grow sick, and leave too soon.

There's a paradox at work; both of the above are true. We’re the product of our choices and survivors of our circumstances, to the extent that we choose to survive. I choose to survive. Thanks to Bill, it occurred to me that if I stop trying so hard to be happy, then maybe I'd have a good time.

And so I did. My husband spoiled me rotten, you wonderful fans sent heartfelt messages, and I wore my tiara out to sushi.

Here's the 40-year-old version of me, tiara and all, and my career goals for my 40th year:

-Publish 3-5 poems in an awesome journal. I just received an acceptance from SWIMM Every Day! Thank you, Jen Karetnik and the editors!

-Wear a tiara, not only on my birthday but regularly just for kicks.

-Secure an agent for my collection of essays, "The Sound of Hunger: Loving & Loathing in the 21st Century." Nothing is for certain yet, but something cool is in the works. Stay tuned.

-Win a major award. Yaddo, anyone?

-To NOT overdose on existential breakdowns. Thank you, again, Bill Berry, for plucking me out of despair.

-Set better boundaries. Thank you, Sarah Colon, for helping me with this.

-Gain 1,000 followers on IG (done!), 10,000 on Twitter, and 5,000 on FB - with the caveat that these followers are authentic, warm, and genuine. And you are.

Thank you for following my journey and allowing me to witness your own.

January 15, 2021

Maria’s Rules for a Healthier Sestina – and Saner You

Today, I’ll provide some tips, both my own and from the Sestina High Priestess, Sandra Beasley, who helped me when my sestina needed triage. Be sure to check out her new forthcoming collection, "Made to Explode," which will grace the world on February 8!

All Writers' Workshop, remember when I taught one of Sandra's poems during our sestina class? Here are my quick'n'dirty tips, many of which I learned from Sandra's Chicks Dig Poetry blog, which has been an absolute lifesaver.

Maria’s Rules for a Healthier Sestina and Saner You

• Play on and with your end words! For example, if one of your end words is “wave,” then try variations throughout. For example, use “microwave,” “airwave,” “wavelength,” and “unwavering.”

• At some point in the poem, ONCE, take the liberty of switching one end word out for a phonetically similar but different one. For example, “wave” could be “Wayne” or “way.”

• Choose OBSESSIVE subject matter. What is a theme that repeats itself over, and over, in life, in YOUR life, in your brain, or for people in general?

• Avoid the “sestina sag” that occurs around when you reach the final sestet. Do this by inserting a turn – a surprise – at that point in the poem.

• Avoid general “sags” by using subject matter that turns. In other words: choose a subject that naturally zig-zags in unexpected directions.

• Personae and dramatic monologue poems ARE AWESOME for sestinas. You can hide the form better, AND when you’re inhabiting someone else’s mind, you can usually advance ideas and narratives to avoid sagging.

December 25, 2020

My Work is Important?! How to Explain that Your Poetry MATTERS

Once upon a time, when I harbored the delusion that I wanted an academic career, during a mock job interview when I was asked, "Why is your research important?" I sat there, gaping like a carp. As much as I still don’t have any intentions of becoming an academic, there was and is still merit to this question.

I now realize that "research" means poetry. At the time, I rationalized that my poetry HAS to possess some importance, otherwise I wouldn't do it. But isn't it, the Midwestern half of me wondered, kind of pretentious to brag and to say that my work is important? Little Old Me, who nobody's heard of?

Then I realized that I needed to stop. If I was going to ascend past the rank of a graduate student to any kind of professional, then I’d need to answer this question, not only for a job interview but also for myself. The question, "Why is your work important?" arises in countless incarnations, not only on the job market but throughout our poetic lives.

The most successful poets I know are scholars. Although they may not write criticism, they think critically about their work. They are aware of the gaps that they are filling in, as much as they consider the omissions. They know who their audience is. They’re able to clearly and concisely articulate the major themes throughout their work, drawing up a larger trajectory.

The fact of the matter was until I came to understand why my work is important, and speak intelligently to that end, then nobody else ever would find it important either. That was the bittersweet truth.

Right now, as I examine the ever-growing pile of poetry books overtaking my loft floor, a quick scan of titles reveals a key and related point: all of the authors whom I’m currently reading, returning to, and obsessing over are authors who know their larger concerns. They’re writing from cultural, racial, and political standpoints, even when the subject matter doesn’t explicitly engage these themes. Jamaal May, with his global preoccupations with social justice and racism, also possesses a personal obsession of Detroit, love, and addiction.

Warson Shire writes of her complicated upbringing as an African woman. She writes the body, particularly the female one while describing the horrors of genital mutilation. Ocean Vuong tirelessly interrogates his Vietnamese-American identity in opposition and in harmony with his queer one.

My friend, T.J. Jarrett is constantly writing new poems that engage the concepts of slavery, family, and resiliency in the face of trauma. Some of my favorite contemporary literary crushes each have one common attribute: they are aware of their larger and personal subject matter, and they know why these issues are important.

Aesthetically speaking, I’d say my work borrows from Plath and Sexton. Among my contemporary influences are Audre Lorde, Mary Karr, Etheridge Knight, Kim Addonizio, and Dorianne Laux. Some of my favorite new writers include the aforementioned Jamaal May, Ocean Vuong, and Iliana Rocha. These writers have influenced me; their obsessive and beautiful renderings of trauma, love, healing, and the body are all conveyed in accessible lyrical/narrative forms.

These authors, moreover, aren’t afraid to be brash and accessible; but they possess empathy and self-awareness towards their subjects as well. The most important aspect that these poets share, however, is the ability to localize/personalize their global concerns.

In other words, each of these writers makes the personal political by embedding his or her work within a narrative, then examining concepts such as war, racism, and poverty through a personal lens. The speaker then zooms away and back from the self, capturing these emotions through different perspectives throughout their own individual poems, and more broadly throughout their full-length collections.

With this realization in mind, as a straight, white, Greek-American woman, I began to more critically examine my own work. What are the larger patterns that arise, the inescapable obsessions threading throughout not only my individual poems but also spanning across my whole books? If I could trace thematic connections throughout my poems and books alike, what are those arcs, and why are they important?

Until thus far, I’ve subconsciously lived with the privilege of denying my body, along with the blissful oblivion of acknowledging my work's larger concerns. Ironically, the best new work out there contains self-awareness. Those who don’t possess the privilege of denying their bodies generally display this heightened sense of awareness; the work that emerges is relevant and evocative.

On that note, I began to think of the ways I should investigate my deeper poetic identity, as well as my personal politics. As a woman who comes from two diametrically opposed backgrounds, who’s lived all over the United States and traveled throughout the world, I’ve never fit into one particular place. I've found the different cultural norms—even from the Midwest versus the West Coast—to be fascinating and alienating.

I realized, throughout my work, I focus on this alienation through the travel-narrative. Therefore, whenever I revisit the travel-narrative, I’m as compelled by the disasters that occur as much as what saves the speaker.

I think of the travel-narrative as a vehicle that propels the speaker into self-examination and the realization that there is no escape. Therefore, she’s left amid glints of machetes, piles of cocaine, and emotionally unstable people only to realize that she can’t keep escaping from herself.

From there, I began to think more deeply about what makes my poetry tick. I realized that my work explores the concept of borderlands, both in the abstract and concrete senses. I’m interested in places that keep us out and, paradoxically, trap us within their real or imaginary walls.

These paradoxes stem from my identity, as a Greek-American woman, who was raised in two completely opposed places: Joliet, Illinois, and Athens, Greece. For this reason, I’ve never quite fit in culturally anywhere. Out east, I was perceived as comparatively withdrawn and laid-back. In the Midwest, I’m read as non-white, louder, and aggressive. In Greece, people are perplexed by my obvious accent when I speak the language. This sense of isolation, travel, and searching will always permeate my work.

Moreover, I’m interested in what happens when we try to escape these unpleasant feelings and cross the borders—literally or psychically—into a different and dangerous place. Whether I’m literally paying the toll and leaving Belize for Guatemala, or exploring the alienation of living on the metaphorical edge, as I do in many of my poems, the speaker’s always trying to escape, only to collide with her limitations.

So, what happens then? When she crosses this "borderland," there occurs an anti-travel narrative, a darker antithesis to Eat, Pray, Love. No, my speaker doesn’t go to Costa Rica where, amid the beauty, she comes to a brilliant realization while she floats away on a surfboard. No. Instead, the narrator tries to escape her past demons by dashing off to exotic places. Except, instead of obtaining peaceful insight, she’s confronted by demons at every turn. And those demons aren’t embodied by the eccentric characters she encounters; those demons are within her. She realizes that there’s no reprieve no matter where she goes. Regardless of how many borders she crosses, she can’t escape herself until she confronts the mess of her life.

And so, as I continue to name those larger themes in my work, I’m now comfortable with describing my poems as an "anti-travel narrative."

Through the anti-travel narrative, my work provides a different perspective of escape. We can never really escape where we’re from, so how can we negotiate our origins, whether they present themselves as our troubled families or our dysfunctional past lovers?

This concept is important because we have to negotiate these difficulties, particularly as women, especially in this current political regime and world, where tragedies inevitably occur. And it’s too easy to give up. As long as we’re signed up to live life, we must and examine what force helps us to live—poetry is that source for me, now more than ever. Whether we suffer or lose an election to a toxic president, or say good-bye to someone whom we love, we must interrogate what helps us remain sane in this world.

My newer poetry reflects that interrogation. That’s to say, my personality and poetic philosophy emanate from the page. I rely on laughter, especially in the face of sadness, trauma, and awkwardness. I don't flinch, for better or worse, when faced with dangerous situations. Although I’m becoming more discerning, I’m still admittedly drawn to wild, crazy, and broken people, if only because I see them as needing love as well. More honestly, I see shades of myself, and of everyone, within these people.

Aside from exploring what motivates us to keep living and loving, another preoccupation strewn throughout my anti-travel narrative includes trauma and resilience. Whether I’m writing about mass shootings, as exhibited by "Aubade in a Burning Bar" or more personal loss such as "Change in Altitude,” I’m not only interested in how we process grief, but how the narrator rises above it. I believe that my poetry (and poetry in general) is important because it facilitates resiliency. At its very best, poetry can help us to recover.

Another major obsession of mine—that’s also situated under the larger umbrella of the anti-travel narrative, trauma, and escape—is abandonment. I write about the larger theme of the speaker's leaving in an attempt to escape her character that is, even in paradise, inescapable. Therefore, the speaker has two choices: either to heal or to die. This do-or-die mentality is precisely why the pantoum appeals to me: because it is the language of obsessive dysfunction, of leaving, then coming back.

Alongside this sense of resiliency, compassion for oneself, and others is paramount. I write about not only abandonment as it applies to the physical act of leaving; my work’s also obsessed with the fear of losing those we love, through addiction, illness, or geography, as well as examining what happens when we leave.

So, why do you write?

First Book Dilemma: How to Write About Those You Love and Those You Don’t Love Anymore

In 2011, when my first book of poems, A Hymn That Meanders, was about to be published, I was hit with a gust of bliss. No, I was drifting through a rose ether. I, Maria Nazos, could finally call myself an author!

Then, gravity yanked me back down to earth.

What would my family say? The book was due out any day, and I’d not shown my loved ones the proofs. I’d written about my family in the same manner that I did everything in life: unabashedly. I’d written about my familial alcoholism, my sea captain father, and my wayward 20s.

On top of it, I’d written about ex-lovers, many of whom I had to make an effort to get away from, most of whom I don’t think much of when I do think of them at all, and that’s putting it diplomatically.

To top that off, at the time, I lived in Provincetown, Massachusetts, a town of 3,500 people. I bumped into these former lovers more often than I would have liked.

This worry led me to my next searing question. How do I write about those I love and those I don’t love anymore, when they may confront me with my own words?

I contacted my beloved mentor, Laure-Anne Bosselaar, for advice. Laure-Anne responded:

“My answer to you is this: speak to those you love and respect that your book will speak of TRUTHS that are yours and yours alone. It is art. Not journalism. But it is also an art so few follow -- so cousin Fred or uncle Joe don't risk much. Tell your family that yes, you are sorry that some will be hurt and that it is out of hurt that you write most of your work. I believe it was Bill Kittredge who once said, ‘If you're not pissing your family off, you're not writing, well!’”

Wow, I thought, I wish I could be so fierce. But I needed some more footholds on this slippery terrain. As if by magic, She Writes, the all-female web forum and publisher, was holding a radio discussion titled, “How to Write about Those We Love and Those We Don’t Love Anymore.”

“Hi, this is Maria Nazos calling,” I stammered as I called into the show. “I’m publishing my first book of poems, and I KNOW for a fact that the people I’ve written most about are going to read the book…because they’re my immediate family.”

The panel chuckled.

The panelists echoed Laure-Anne. Write your truth, and yes, there is more than one. Yes, my loved ones had as much of a right to respond to my work as I had to write about them. My loved ones were entitled to say that I’m wrong, inexact, cruel, obscene, repugnant, that I used my family and friends as a confessional Kleenex.

Annie Dillard believed that a writer should never write about another individual unless that other person has his/her own platform from which to respond. I respectfully disagree. I elected to become a writer to make sense of the chaos that was my life, just as much as writing chose me.

On the She Writes radio show, one caller shared a positive experience: she’d written about her philanthropist parents. Her parents read the first draft of the book and said, “We don’t agree with everything, but we know that you can make this more truthful.” So, the woman took the book back and revised it. The book became a bestseller.

On the darker end of the spectrum, another caller described how she’d written about her family and gotten terrible reviews from family and critics alike. She’d never written again.

Rosanna Warren was visiting at the time, during my 2011 fellowship at Vermont Studio Center. I asked her what she thought about this matter. Rosanna felt that as we grow as writers, there are varying angles from which we can examine our subject matter. For example, in one group of poems, she’d written about caring for her dying father.

“But in one poem, I found myself taking a drastically different stance,” said Rosanna. “I found myself writing about metaphorically gorging myself on spoonfuls of my father’s illness. That poem was symbolic for my guilt that I felt while writing about him.”

Rosanna also maintained that an important step is to be aware that the invasion of others' privacy is a serious question, and one must find a way to incorporate that question into the structure of one's own writing.

At the Vermont Studio Center, I read aloud one of my personal essays about intergenerational alcoholism. I was so nervous, the wine I had consumed was seeping from my underarms.

“What do you think?” I asked my peers.

One woman said, “Are you kidding? I’d be proud if I were your family. They had such a tragic, lovely life.”

Then it hit me: not only is there more than one truth, but also hopefully, my writing is good enough to where it speaks numerous truths. I’m not demonizing my family, but depicting them as flawed, graceful individuals. Many audiences might even find the story of my family and parents—a young rebellious woman of the ’60s, who abandoned reason to sail the world with my Greek sea captain father—to be a tragic and exotic story.

I feel very lucky. I’ve gotten to hear some diverse opinions. It’s now 2020, and I’m still awaiting my family’s response to the book. Since then, I’ve heard from the other people I’ve written about and welcomed or cringed from their reactions.

Two years later, when I began my first year in the Creative Writing Ph.D. program at The University of Nebraska-Lincoln, former U.S. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser, who was on the faculty at the time, paid my first collection mixed praise.

“It’s a remarkable accomplishment, and its energy never lets up for an instant, cover to cover, as if there were a blue flame burning under all of it. As Emerson wrote to Whitman, ‘I greet you at the beginning of a great career.”

Well, I could have died right then as a happy woman, but then he delivered the criticism:

“As to your family: I’d guess [they] feel exposed and defenseless. Had I been your mentor, I would have advised you to hold [some of the poems] back and would have cautioned you against some of the descriptions of [familial] drinking in some of the other poems. Though you and I might disagree about degrees of propriety, no poem is important enough to risk hurting someone else’s feelings.”

The letter is dated back to 2013. I still have Ted’s response framed above my desk because to this very day, I remain as conflicted about his advice as I am about that first book. Yes, as writers we ought to err on the side of compassion. No, we shouldn’t sit down and intend to break someone else’s heart, but what if they broke ours, over and over? Should we be forced into silence because our experience wasn’t pleasant? Do we then sign a vow of secrecy, a refusal to acknowledge our suffering, too?

I don’t know the answers to these questions, but I think they’re important ones to ask, ones that to this day, hang like icicles above me.

I understand that I made a deliberate choice to publish that book without even sending my family the proofs, for godsakes.

I also contend, however, that I’m a poet, not a babysitter. I refuse to sit in watchful passivity over my subjects’ emotions. However, I also do have a responsibility to care for my subjects as I write about them. But in this world where “reality” TV and, for four nightmarish years, Donald Trump served as sources of “truth,” now more than ever, I feel an even bigger responsibility to speak my own.

This essay originally appeared in Boxcar Poetry Review

Tips for Handling the Rejection Letter

I don’t mean to come off as overly idealistic. I can't feed, clothe, and provide compasses to all the lost, broke, talented, and up-and-coming writers out there any more than I can sustain myself. What I can do, however, is talk about submitting to literary journals from an empathetic standpoint, if only because for the last nine months, I’ve done nothing but sit, write, and workshop poems in a weekly group, and submit them.

The past year has netted some great results. It has also netted some failures, known as form-letter rejections or emails. Here is how to get back on that eternally bucking literary pony and ride it through the rejection surf:

You aren’t sending out enough. When you first start sending out your work, I encourage you to simultaneously submit but only to those journals that allow you to do so. Keep track of the journals that you send to. Withdraw individual poems once they are accepted, but until then, think of yourself as being alone in a desert or forest, cut off from all resources. That’s how it is when you’re a post-MFA emerging writer. You need to take that big pile of poems that’s been sitting there on your desk for the last three weeks and spread them around or save your best poems for excellent journals that refuse simultaneous submissions.

You take rejection too personally. Don’t. I assume you take your craft seriously. If you take your craft seriously and you try hard enough, then guess what? Someone else, like the editor of a reputable journal, will someday also take said work seriously!

Your formatting or aesthetic is wrong for the magazine. If you have read my poems (www.marianazos.com/poems), you will see that my lines are sixteen syllables long or more. Once I submitted to a well-distributed, well-respected literary review, and I got a rejection with a handwritten sentence, “Your lines are too long for our magazine’s size.”

Really, I thought to myself. So, the first time around, lineation could have been a contributing factor? The answer is sometimes a resounding yes. Many editors simply will not publish your poem due to limited space in the journal. I’ve had to reformat my long, breathy lines twice already, chopping them down to fit a perfect-bound publication.

The editor is having a bad day. Editors are people, just like us. They have good days, great days, bad days, and so-so days. They get indigestion, have fights with their partners, and their toilets overflow. They have car insurance to pay, dogs to walk, food to cook.

I always had this image of editors sitting in a Manhattan-based office with black berets, enveloped in a cloud of clove cigarette smoke. Sometimes, I envisioned all editors as tenured professors at reputable universities who have the time to read each poem with careful attention to quality and craft. Here's the deal: editors embody all kinds of people; we try our best. Sometimes, a good poem slips through the cyber-cracks; sometimes it just isn't our cup of tea. And yes, sometimes, the work just isn’t good enough.

As for any personal rejections that you receive? This note equals encouragement, but never a guarantee of an acceptance if you resubmit to the journal. So, treat these kind words like the hot date who never called you back: keep a fond memory, don’t try to read too deeply into the tone, and chalk it up to your growing experience.

You didn’t send your best work. Be brutal with yourself. Did you send them your best, polished, roaring, crazy, singing poetry? Or were you so eager to send something off that you send a semi-revised sonnet with sloppy line-breaks? Before sending anything out, take your poems through a rigorous process of revision.

Here's my process: write the poem. Revise it some, thirty to fifty times—that has been my magic number, but I am sure you have your own—then let the poem sit for a few months. Pick it up again and read it in a detached manner. Make one last editing change, then show the piece one last time to an MFA workshop, online, or a trusted friend. As writers, we’re the worst judges of our own work. We need a different pair of eyes, if not several.

You didn’t see what kind of work the magazine published. For all you know, your work could be too edgy, too Language-y, too confessional, far too formal, too long, far too short. Realistically we can't go out and subscribe to all the amazing journals out there. That said, most journals contain some sample poems on their page. And if you’re going to spend money on anything, a subscription to a good journal costs as much as three lattes. As my grandmother used to say: "If you want to get love, you've got to give love," so show those venues some love.

The Association of Writers and Writing Programs is a great resource for purchasing discounted literary journals. Make a list of journals that you would die to have your work appear in. Then, hit up each table, buy those issues, and read them thoroughly. Ask yourself, is this the kind of journal you’d want to see your work appear in? Is this the kind of journal, moreover, that would publish your work?

If there’s any other advice that I can offer, it is this: fail magnificently. When you get that deflating email, throw a shoe, get a drink, and then begin the arduous process again. Although there’s no formula to anything, the most successful writers I know generally share two qualities: self-forgiveness and patience. It IS a choice to put your work out there and in a world where the humanities are struggling, the act of writing, submitting, and subscribing is an all-sustaining endeavor. Nobody owes us anything, acceptances or otherwise, because we chose to become writers. Meanwhile, we can choose to fail magnificently as we stumble on.

After Biden’s Election: An Open Letter

Last night, Biden delivered his speech. Today, I have one of my own. I've noticed a trend among Trump supporters, both on social media and in-person, and I need to call attention to it. Before we make reparations, I'm not ready to move forward until I can point to the source of my rage. Now that Trump has lost, the common response from supporters is, "I will pray for everyone."

Here's the deal - I don't want your prayers. I'm tired of God and prayer blindfolding truth and morality, posing as a fallback after the fall of a sick, authoritarian leader, and serving as a protective buffer against your loss.

I don't want your prayers. I'm tired of prayers that signify nothing more than surrender when you haven't gotten your way. These prayers represent nothing more than a weakened self turning your power over to another all-encompassing force because your leader has lost.

I don't want your prayers. Where were your prayers after George Floyd gasped his last breaths beneath the knee of a murderous police officer? Where were your prayers, as Breonna Taylor's family suffered and as her killers walked free?

I heard your silence. I saw your blank Facebook walls. I saw you defend white supremacy. I saw you refuse, STILL, to call Trump out. I saw you rebut, "All Lives Matter," while your Black friends patiently explained how they are STILL suffering.

But I did not, ever once, see you post or say a prayer.

Where were your prayers when immigrants were locked in cages when their bloated bodies rose up from the water? Where WERE YOUR PRAYERS when our soon-to-be-former president continued to hunt down undocumented immigrants as if they were his White Whale?

I DON'T WANT YOUR PRAYERS. Did you ONCE pray for the 240,000 Americans whose families died due to COVID? Or are you praying because your authoritarian madman, who offered you a temporary respite from responsibility for your decisions, has lost?

Here's what I want: I want you to admit to your defeat, your bias, and your fear of a world that is changing. I want you to admit that you're turning our real problems, such as climate change and global warming, over to a supreme force.

So far, all I have seen is you turning to a blue-eyed lord, praying to and for white faces. Can you open your eyes to the pain and suffering around you, to make a vow of empathy and compassion? Can you include the Black community in your prayers? LGBTQIA people, and immigrants? Can you begin putting into writing and words prayers for those people, too?

Can you examine a life that is fraught with suffering, and at the root, a lack of kindness, privilege, a refusal to see others? Can you pray for what others experience, not just you or a fallen dictator? No God will help you or me out of this one. We can only help each other.

So, I send back your prayers. Leave me out of them until you begin to examine those you leave out.

Then, maybe, I'll want your prayers.