Maria Nazos's Blog, page 2

April 7, 2024

Come out to Larksong Writers Place on Tuesday, April 9, at 7

Come out to Larksong Writers Place

I can't wait to guest-read with featured writer Kate Gale of Red Hen Press at Larksong Writers Place! I'll read from my newest book of poetry translations, The Slow Horizon that Breathes (2023), from World Poetry Books. I'll also share poems from "PULSE," forthcoming from Omnidawn Publishing (2026).

Here are the deets:

DATE: Tuesday, April 9, 2024

TIME: 7 to 9 pm Central Time

FEATURED AUTHOR: Kate Gale, author of "Under a Neon Sun"

GUEST WRITER: Maria Nazos

LOCATION: Larksong Writers Place

1600 N Cotner Blvd, Lincoln, NE 68505

March 3, 2024

Life Begins at 40…Neurodivergence, Self-Forgiveness, and a New Book

Before I blew out my 43rd birthday candles, my husband reminded me to make a wish. I realized something incredible: I had everything I could want. My forthcoming publication of “PULSE,” from Omnidawn Publishing, my second, long-awaited collection of poems, is one of the miracles.

There are so many more: my husband, my friends and students (you know who you are), my new job, and supportive coworkers. The last unexpected blessing was the confirmation that I am delightfully neurodivergent.

The day after my 43rd birthday, I received an ADHD diagnosis to complement several other preexisting conditions, including traits or diagnoses of OCD, PTSD, dyslexia, and dyscalculia. It’s funny that my brain localized all those acronyms close to one place.

The greatest gift you can give anyone is being yourself. There is a saying that life begins at 40; I agree. I’m just barely getting started.

My life now makes so much more sense. Since childhood and throughout much of my adult life, what others dubbed quirks, spaciness, and eccentricities seemed to culminate in perceived weaknesses.

The terrible standardized test scores. The awful math grades. The generally awful school grades. The inability to sit still. Always being in trouble for talking back. Getting teased by friends because I couldn’t understand how to play a simple card game. Getting teased by adults later in life because while working my many cash register jobs, I could NOT count back change, or money, to save my life. I also lack spatial relations, LOL. You do NOT want me to parallel park your car.

And yet, I have so much to be thankful for leading up to now. My unique brain chemistry has gifted me with a photographic memory. As I discovered in my later adult years, my strategic ability allows me to thrive in the workaday world because my mind works so quickly that I can look at websites and marketing strategies and create a smooth strategy. I published one of the few or first pantoums in The New Yorker. I crossed borders by myself, from Belize to Guatemala. I’ve had Balinese medicine men put their healing hands on me.

The most moving part of this journey is giving grace to that child, teenager, and adult who was not like the others. It means thanking the people who saw and see me throughout the years. It means forgiving family members, teachers, acquaintances, and former service industry bosses who attached synonyms for “dumb” and “weird” to my name, or at least saying to them I made it. So there.

The way I gauge whether I “made it” isn’t through the above accomplishments. It’s whether or not I, at 21, would’ve wanted to have a beer with me now. The answer is yes. I’d have a beer with me. I’d think I was A-OK and pretty cool.

I wish you and all your future selves the same. 💓

November 11, 2023

Celebrating Ominidawn’s Publication of “PULSE,”

I have incredible news to share, but first, I want to tell you about my world leading up to it.

Fifteen years ago, I published my first book. Fifteen years later, I struggled immeasurably.

What I hate most about my industry is that we take ourselves so seriously. We opt for polish over humanity when that’s what makes our writing worth reading. Our real bios are the ones spattered in grit.

Not me. Not today.

I’ve shared snippets here and there of my past, but never the whole thing, not because of embarrassment but because there’s a lot to the story.

Here’s an abridged version of my life until the present moment:

2002-2007

• Took my MFA in New York City, ready to conquer

• Sent out work, getting rejected relentlessly,

• Worked every job imaginable and scraped by on food stamps

• Moved to Provincetown, MA, and spent eight years cleaning hotel rooms, working as a whale watch boat attendant, selling sunglasses, and teaching community college

2007-2012

• Crazy ex stalks me for a year and a half

• I end up homeless for another year and a half, surfing on couches

• I recovered from PTSD. Kept living on the Cape, working odd jobs

• Fed up with the minimum wage, I apply for PhD programs

• Mentors tell me I’m not cut out for academia due to my dyslexia and poor test scores

• I Googled PhD programs and found one in Lincoln, NE, that doesn’t require GREs

• Got a full fellowship to the University of Nebraska-Lincoln

• I melted down my gold jewelry to scrape together enough money to move

2012-2017

• Drove across the country to Lincoln, NE

• During the PhD program, I publish in The New Yorker

• I met my husband, fell in love, and stayed in Lincoln

• Ten years after my first book, I finally pulled together another collection of poems, “PULSE,” as my thesis

• People say my career will explode; it doesn’t

• I keep sending the book to contests, making EVERY finalist pool, and then nothing

• I tell myself I’ll wait and fight for the RIGHT publisher, someone who is kind and who COUNTS

2017-2022

• Took my Ph.D., left academia for good, and pursued a digital marketing career

• Agents expressed interest in “PULSE”; then they didn’t

• Publishers express interest; then they don’t

• “PULSE” keeps making book contest finalist pools

• I put the book and poetry aside for a year

• Finally, I return, refusing to give up. Just like a heartbeat, I will not stop listening to the poems

2023

• I send the manuscript to Rusty Morrison at Omnidawn Publishing

• In 2026, Omidawn will publish “PULSE”

• Rusty, the editor of the press and a splendid teacher, editor, and poet, and I are happily working together to find the book’s best self

If I sound proud of myself, that’s because I am.

I have love for too many people to name who put up with my tantrums and resilience over the last decade and a half. Rusty Morrison, Deb Hicks, TJ Jarrett, Rick Christiansen, Emily Simmons, Martin Espada, Bill Berry, Travis Russell, Jayne Marten, and countless others.

Keep listening to your heartbeat.

July 20, 2023

Open for business & scanning new horizons!

As I scan the horizon for my next career, I’m looking for a place I can call home.

I also realize that so much of my transformation manifested right here at home this summer due to the privilege of taking a break.

As a result, I want to open up my creative and life coaching services for anyone who might need them.

A few years ago, a woman emailed me, “What experience DO you have as a life coach, exactly?”

I immediately felt like an imposter. She was right, I thought to myself. I don’t have an official certificate. Who am I to call myself a life and creative coach?

And so, I metaphorically closed the curtains on my dream. I took down my Google listing. I removed my website bio.

Nearly two years later, I realized how ridiculous I was. Of course, I have the credentials and the success to help you.

In this case, the achievements aren’t mine - they belong to my beloved students, clients, and friends.

Chances are, if you’re reading this post right now, one of these many successes is yours. Don’t be afraid to comment; take credit for our work together.

Does one or more of these success stories apply to you?

🎓 You’ve been accepted to competitive internship programs and Ivy League schools thanks to your talent and my support.

💷 When you took one of my classes, you decided to change your major to English, graduating with a fulfilling career.

📜 I helped you get a job by reviewing your resume or contacting the right peeps.

✏ You have gone on to publish poems in reputable journals because your work is just that fricking good and because I pushed - and continue to push you.

🗞 You have gone on to attend highly competitive MFA programs, a destiny you deserved, but needed a push and killer new poems due to taking my class.

So, to respond to that woman who emailed me and my inner critic: Yes, I have experience as a life and creative coach. And I’d love to help you out.

I also decided to ditch the prices and work with people on a case-by-case basis.

So, if you have:

🖋 Poems to publish

📰 Career or academic materials to revise

👣 Or want a loving kick in the butt? Here’s looking at you.

DM me. See less

March 3, 2022

Mistakes You're Making That Screw Your Writing Career: Ways You Can Undo Them and Get Published

Here’s what I have to say about some moves I see folks making that may cause setbacks on their writing paths. But, luckily, it doesn’t mean the end…take a look at the following tips to help get you back on track and moving forward.

Not Submitting to Competitive Journals

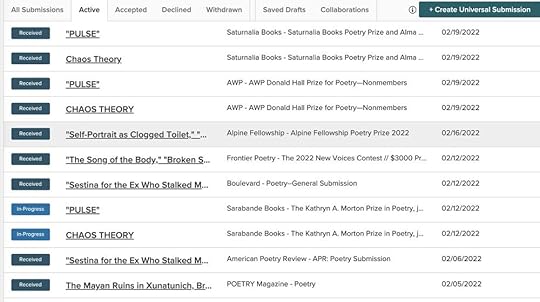

The way to success is to aim high. Here’s a photo example of what my Submittable account looks like at any given time. You’ll start to see results when you broaden the scope of your submissions.

I always tell my mentees to submit to a good mix: top tier, middle tier, and smaller journals and presses. Listen, I could scroll through a whole slew of rejections I had to muddle through before that New Yorker acceptance came in, people.

Plus, the more you submit the stronger your submitting chops are becoming. Your name is sticking to the walls of the minds of readers. You’re doing the necessary work.

Publishing with Unsupportive Presses

So often I see poets putting together and publishing chapbooks with unsupportive presses—meaning they do very little to help guide you through the process or don’t have the resources or funding.

Publishing individual poems in excellent journals is even better—oftentimes you’ll get even more attention and networking possibilities. Don’t be afraid to ask some of your peers or favorite writers where they have published and what their experiences have been.

Failure to Network and Keep Up Social Media

Social media and networking in general is so important to succeed in the publishing world. In reality, it’s pretty much imperative for any business these days—from a new café to any solo entrepreneur.

I always suggest keeping active platforms on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook if you find your community active on any of those. Once you start up these platforms, try to keep up with a posting schedule that fits your lifestyle—whether it be 2-3 posts per week or month—as long as it’s consistent.

One last note I’ll leave under this category is don’t forget to interact with other folks’ content! Remember, you’re building a community around you and the only way to support that community is to build each other up in a communal way. So don’t forget those likes, comments, saves, shares.

Being Entitled, Whiney, Arrogant, or Mean

Maybe in the 1970’s or 80’s people went around being rude to each other in order to gain upwards mobility. Today that is not the way you navigate the literary scene! The writing world seeks compassion and kindness towards others—focus on treating those around you well and the same will come to you.

Publishing Too Much, Too Quickly

This is a quick career-ender. I see this happening all too often with younger writers—they gain a sizable amount of traction very quickly and then burn out or get quickly forgotten. Instead, focus your efforts on something more longterm. A steady and consistent rate is better than a quick zap and fizzle. Take your time. You have it.

Not taking risks

That being said…do take risks! This links back to aiming high. Worst case scenario whatever you applied to or pitched doesn’t work out. That’s ok, move on. Move on to the next one. One of my mentors, a highly successful poet today, once told me that they applied for the Guggenheim Fellowship 11 times before receiving it! 11 times! Each time they submitted, that was a risk worth taking. Be persistent.

Not Giving Back

Linking back towards building community: you’re cultivating it and it will take care of you once you do so. So not only does that mean building those up around you, it also means taking part in workshops, conferences, etc. Be active and participate. You’ll find it has a reciprocating effect.

Those are my tips for success! Best of luck!

January 4, 2022

How do you write about everything from joy in response to death to a first blowjob? Find out in January’s workshop!

How do we question and harness retribution and anger in our poems? How do we pull light and heat from rage? Mostly, how can we get away with being our best mean person on the page while honoring our own ethics, integrity, humor, and readers? In this workshop, be prepared to curse, apologize for sins you’re secretly glad you committed, and reveal edgy confessions.

Throughout this eight-week generative course, we’ll explore various poets (more on that below) who manage to get away with risky confessions, potentially volatile statements, and controversial revelations. What keeps us as distant readers engaged? When are we turned off?

Is there a way we can ethically invoke shock, discomfort, AND compassion toward ourselves, our subjects, and our readers?

A good part of the class will then be devoted to creating our own virtuous “mean-person” on the page through a series of optional, guided writing prompts. You’ll also explore free-verse and lesser-known poetic forms and themes, including the golden shovel, cento, ottava rima, and abecedarians.

Here’s a preview of the many facets of ethical bitchiness:

Complicity—nobody gets off the hook

See the fearless humanity in the other entity

Humor

Essential Information

Metaphor as a vehicle for transformation

More to be discussed in course…

Each week will focus on a central theme of our ethical bitchiness. For example, one week we may focus on sex, the next week, trauma, then family, race, etc. We’ll be discussing a multitude of poets, such as Laura-Anne Bosselaar, Wanda Coleman, Ocean Vuong, Kim Addonizio, and Tommye Blount.

Let’s take a look at several ways Meg Kearney shocks her reader in “First Blow Job”:

Suddenly I knew how it was to be my uncle’s Labrador retriever,

young pup paddling furiously back across the pond with the prize

duck in her mouth, doing the best she could to keep her nose in the air

Right off the bat we have humor: Kearney compares herself to a dog, and metaphor as a vehicle for transformation: it’s clear (especially as we continue reading) that the speaker is using the act of a swimming dog to mean something else in the speaker’s life. Ending the stanza with “doing the best she could to keep her nose in the air” is our first cue that this comparison is leading us somewhere deeper.

so she could breathe. She was learning not to bite, to hold the duck

just firmly enough, to command its slick length without leaving marks.

She was about to discover that if she reached the shore, delivered this

We see complicity—nobody gets off the hook with lines like She was learning not to bite.

duck just the way she’d been trained, then Master would pet her

head and make those cooing sounds, maybe later he’d let her ride

in the cab of the truck. She would rest her chin on his thigh all the way

home, and if she’d been good enough, she might get to wear

The rhinestone-studded collar, he might give her a cookie, he might

not shove her off the bed when he was tired and it was time to sleep.

In the last line, we see the fearless humanity in the other entity as the speaker humanizes the subject. We get the first humanizing description of the subject: “he was tired”. The speaker gives weight with the placement—the one offering from the inside perspective of the subject appears in the last line, leaving the reader to chew on that the longest.

For more discussion points like this, sign up for the workshop, through Larksong Writers Place, to try your hand at excavating your own shocking self or ethical bitchiness on the page. We’ll interrogate other poets as well as each other’s work. See you there!

November 24, 2021

Poetry and Publicity—What’s So Important?

I am going to tell you about the importance of self-promotion. As poets, why must we blow our own horns and sing our own praises?

One of the craziest outcomes of sharing your own accomplishments, is not only propelling your own poet path, but also encouraging folks around you to strive for more. In turn, that also amplifies the poetry community even more—more recognition of the poetry world allows it to grow bigger and better.

Make it a practice to share your accomplishments—blast it out on social media, shout it from your window, or shoot it out to all your group-texts—even if it’s small! No success should go unnoticed. This is how poets have to do it—building ourselves up and in turn, reaching out a hand and bringing others to the top with us.

There was a time I found myself getting pissy because I'd see people always getting asked to do readings, conferences, etc., and I was feeling left out until I realized that I had to speak up on my own behalf, even if it felt terrible and awkward and shameful. I now know that those emotions is just the ego trying to keep me safe.

Once I began pitching myself—posting, etc—I stopped being invisible, and maybe that too was equally scary. But I began getting asked to do things. And though we cannot always 100% influence one's career trajectory, refusing to remain silent is a surefire way to give our best shot at being seen and heard - if that is what you want.

Some people just want to put writing in a spiral notebook in a drawer and there is nothing wrong with that. But if your goal is to connect with distant readers, then start with family, friends, and keep going from there.

But, Maria, I don’t yet have the published work to laud!

Before we praise first we submit, submit, submit. A great place to start excavating the various sites to submit is Entropy Mag, which puts out a list of where-to-submit places and updates every three months. Take a peek—there are still tons of journals, presses, awards, fellowships, and residencies to apply to before the end of December.

Ok, but what if I get rejected?

One of the most surprising things to ever happen to me early on in my writing career was when a highly-published poet I knew showed me their Submittable account—the pages and pages and pages of grey little declined boxes scrolled by with the occasional blip of a green accepted.

If you want to publish, the key is consistency.

Rejection is fuel—it pushes you to move on to the next opportunity. Harness the anger and catapult yourself to the next opportunity before the anger fizzles too long into resentment. It’s like cooking caramel, you must catch the heat at precisely the right time—just enough heat brings sweetness...too long on the burner and it turns bitter. Of course, the bitterness can help you too if it pushes you to get stuff done.

Pitch yourself

As a poet you can hardly be passive. Almost all “successful” (a term we’ll use here as someone who is comfortable with themselves and their work and also is somewhat published) have had to land opportunities themselves.

Poets, compared to fiction and non-fiction writers alike, are less likely to use agents. Why? According to Kevin Larimer in Poets & Writers, it may be due to a myriad of reasons. One of them being that literary agents usually get bigger pay-offs from longer works of fiction than they do from books of poetry.

However, it looks as though currently there are “now more early-to-midcareer poets with literary agents than ever before.” This may have to do with the increasing relevance of poetry, as people turn more and more to poems to speak to hardships like the Black Lives Matter movement and the Covid-19 pandemic. Even small victories like having a poet perform at the Superbowl is a big win for the poetry world. (Check out Amanda Gorman)

As a poet, there are other ways beyond an agent, such as hiring a publicist, putting effort into social media, etc. so that we aren’t just reliant on winning contests. Winning contests is not the only way to publish or get noticed!

The point here is that as poets, we have to keep pushing ourselves. The only way is the way forward.

To read more about poets and literary agents, see this article here.

Sign up for my newsletter, here, at the bottom of the page.

September 10, 2021

How are you celebrating National Translation Month?

In honor of National Translation Month, I thought I’d share a little bit of my past experience with translating work. You can find some of my past translation work in Drunken Boat, where I have several poems by Dimitra Kotoula published.

I chose to translate Kotoula not only because she is among a unique generation of poets, but also because of her delicate maneuvering of tonal balance. As a translator, I act as the person in the liminal space between Dimitra’s poems and my English versions. I’ve grown to know and love her poetry, even though she challenges her readers and her work is so different from mine. I understand more of the nuances, and my Greek has improved.

I want to talk a little bit about the process and some of the difficulties I faced as a translator. Firstly, my biggest challenge was remaining true to both meaning and music without compromising the poems' political sensibility.

It has been a challenge to try and render Kotoula's poems in the most accurate light, as they have been written during the current Greek financial struggle, which although is not always at the forefront of the poems, is always lurking at the periphery. There were moments when I struggled to stay as true to the poems' meanings as possible while preserving their musicality.

In order to keep the mood and influence intact, I had to keep the sociopolitical tragedy in the back of my mind while translating the poems. In addition, many of Kotoula's poems are about the act of writing poetry itself, though most moments she prefers not to be explicit about this. Instead, she relies on an intelligent reader's inference, which was difficult to portray as a translator.

While adapting Kotoula's work into English, she and I have exchanged extensive notes back and forth—elucidating images, explaining verbs, and finally negotiating certain mythical allusions or Greek colloquialisms that could have otherwise been lost en route to the English language.

As a Greek-American woman, I had to bring my knowledge of Greece's current turbulent state of affairs, my own clouded memory of living and speaking in that country, and finally, all of the perplexing emotions that accompany being uprooted from one home that I never quite fit into, then transplanted into another one.

In a very real sense, throughout this journey, as a translator, I was going home and getting lost at the same time.

To continue your celebration of National Translation Month, curl up somewhere cozy and check out this selection of poems in translation. I’d also like to point you in the direction of poets who self-translate (an interesting process in and of itself). Some poets to check out are Raquel Salas Rivera, Ana Portnoy Brimmer, and María Luisa Arroyo.

When talking about the process of self-translation, Rivera notes, “Translating my own poetry has been a way of healing my relationship with a bilingual self who struggled intensely to learn standardized dialects of both languages.

For a long time, I was bilingual in contexts where monolingualism was encouraged. My bilingualism was treated by my teachers, professors and peers as something that had to be contained, a dangerous and infectious substance. Each language could spill into the other, leaving unwanted traces and incomprehensible words. By translating these poems, I am acknowledging that US imperialism’s economic impact has led many Puerto Ricans to migrate to the US, where speaking English and surviving are synonymous.” To read more about what they have to say about the process, visit Waxwing.

If you’re interested in reading some self-translated books, you can check out the catalogue at Bilingual Press.

Sign up for my newsletter here, at the bottom of the page.

August 15, 2021

Borders, Boundaries, and Bodies: Returning to Mykonos for the First Time in a Decade

As a bicultural woman who came from my sea captain father’s Mykonos, Greece to my Midwestern mother’s Joliet Illinois, I have never fit in, not in either place, or I have only now, ironically in Lincoln, Nebraska, begun to feel as though I have a place.

Over the years, I erected boundaries within myself to keep people from coming in; I was fearful of what they would find, because I did not truly know what was inside of me. I can say with confidence now, having done (though not completed) the work of the soul, that once I began giving people myself, in my cut-and-dried form, I began giving them and myself the greatest gift of all. I consider my exploration, devastation, and integration of boundaries throughout my work to ultimately be responsible for this major spiritual shift. I don’t worry about swearing when I teach, or sharing personal details, or even crying when a student tells me about how she cut herself deeply enough to bleed, but luckily, not deeply enough to die. In my personal relationships, I find myself stating what I want and not second-guessing myself as much. No longer do I give my power away, either with excessive apologies or self-deprecation.

Of course, there are many different systemic efforts which contribute to this personal feeling of fulfillment: from obtaining my PhD, experiencing a deep and gratifying love, to celebrating Lincoln in its unexpected kindness and warmth, all of these turning points have cultivated my newer, more purposeful self. I would also argue that, the exploration of boundaries throughout my work has also greatly assisted in pushing me, like a leaf, closer and closer to my ultimate destination which is as expansive and open as the sky and its prairie, or the Mediterranean Sea. Finally, my two disparate worlds, my ocean and my cornfields, have managed to impossibly come together. Finally, I feel as though the impossible borders between the two have met so that the ocean is lapping at the prairie’s shore. This has been, metaphorically, what has happened throughout the past five years spent translating from the Greek, writing my own work, and bringing them together.

Perhaps, then, this is the perfect time to write this final section. In short, both my translations and poetry have taught me, both aesthetically and personally, that boundaries are essential to my life. Boundaries, establishing and crossing them, have been the sole reason why I have finished graduate school relatively sane while teaching fifty students and taking three courses. Boundaries, moreover, are the reason why I managed to cross the border from Belize into Guatemala by myself, exhausted, strung-out, and completely heartbroken. Boundaries are the reason why, before crossing the border, I stayed up with a fellow named Ruddy, who by then had expressed both his love for armed robbery and for me: during that painful time in my life, when I had exited a six-year relationship, I was interested in erecting, testing, crossing and transgressing my own comfortable boundaries.

This leads me to why my translations and writing are alike. Whereas my writing engages physical boundaries— taking back power, feeling sufficient, understanding where the speaker begins and the world ends—my translations entailed testing and crossing into a very different boundary into an equally exotic terrain. Translating Dimitra, from the Greek, meant that I had to return, both physically, intellectually, and emotionally, to a place and a language that I felt previously and intentionally alienated from.

On the other hand, my translations required that I return to Greece to meet with Kotoula, a place where I felt a simultaneous longing, hatred, and nostalgia. Once I moved to Greece, at the age of five, my mother descended deeper into a hole of delusions and never resurfaced. She hated the constant strikes that left us without electricity. She hated the stray cats who screwed, yowled, and reproduced all day, every bit as much as she hated their kittens, both the bright-eyed newborns and the stillborn which she had to bury in the unyielding earth. It was throughout my time in Greece when my parents’ boundaries towards us and each other gradually dissolved; I could hear them screaming and fucking in the next room. During the day they would sit at the coffee table together, panicking over countless stacks of bills, unpredictable stocks, and rising school tuition. Meanwhile, as the boundaries dissolved between our roles as parents and children, the boundaries between my parents continued to heighten. My mother began to spiral further into her drinking and delusions. Pretty soon, she no longer even sat at our tiny coffee table to argue over bills with my father because she was sleeping until noon. Our father began to become distant and removed, like those times we would go swimming as a family at the beach, and I would watch him swim out so far into the distance, I would worry, rightly, that he would never come back.

Moving to the U.S. yielded even more problems which I will not go into here. All I will say is that the boundaries both continued to dissolve and grow. Understand, now, when I say that returning to Greece to meet with Kotoula, for the first time in ten years, posed as a massive discomfort. My return to Greece meant that I had to take down the boundaries that I had successfully constructed between my parents, my language, and my painful memories of my mother’s dissolution. Moreover, returning to Greece would make all of these instances palpable, more real. I could not crowd out the noises with rum. Now my pain was real. Similar to my poems, however, retuning to Greece meant that I could no longer deny the difficulty of tensions of growing up bicultural to two very different parents. In Greece, because I attended an American school, and because my mother refused to allow us to speak Greek in the house, I had adhered to her boundaries which she created for fear of losing us to a culture she had never completely fallen in love with. Therefore, I never fully assimilated to the Greek culture. As a kid, people said the same thing to me when, ten years later, I opened my mouth to speak my native language: “You have an accent,” they would say, rather disappointedly. When I moved to the U.S., on the other hand at thirteen years old, I was the Weird Greek Girl. As a result, I have always felt lost among the different places where I go, carrying two disparate and alienating, albeit defining heritages. I am a true mutt, in a very basic sense. And I have had to create my own boundaries in a effort for survival and preservation.

Thus, when I returned to Greece to meet Dimitra, my shock was inevitable. I was astounded to see how the financial crisis had impacted people. I was shocked, paradoxically, to find that my father’s home in Mykonos, had gone from an old black-clad Greek granny’s home which smelled like the coatroom of a Greek Orthodox church, to an upscale vacation rental with marble floors, new rooms, and high ceilings. I was even more shocked, still, to behold the island: the once Bohemian place where I could wander to small neighboring towns at night alone, where on the main drag, my friends and I would drink Sex on the Beach shots with equally Bohemian tourists from all over the world, had since become a five-star resort. Most all of, I was saddened to see immigrants from Syria and other struggling countries, along with the native Greeks, standing at the edge of a dangerous financial precipice. With a whopping 25% unemployment rate and the inability to withdraw more than 65 Euros from the bank, having seen the laments resounding throughout Dimitra’s poems manifesting first-hand was a heartbreaker and eye-opener at the same time. In that moment, I realized that if I wanted to successfully translate her work, I’d have to open my eyes and my heart and return, as Joseph Campbell’s hero does, back into the lair. I would have to cross an entirely different boundary, this time not escaping, but instead re-entering a country which was possessed deep personal, familiar, and sociopolitical tumult. As I beheld my aging parents, my financially struggling aunts, and a strange new Asian-inspired Greek food, I realized that, just as I was no longer the same person as I was at twenty-three when I last visited Greece, or at thirteen, for that matter, when I left, neither was anyone else. At the same time, certain people and things had changed for the better. I am also happy to report that most of the Greek islands, according to the natives, were not impacted as harshly by the financial crisis due to their vibrant tourist economy.

During my time back in Greece, a stark reality was apparent: there was no escaping across a border. With both of my parents together, while I stayed in their guest house, all of my boundaries dissolved, from my seemingly bisected Midwestern-Greek heritage to my own personal comfort—I was staying in a guest house, after all. I watched in horror as, at my favorite peaceful beach, a group of trust-fund millennials ordered a glass cooler the size of a fridge stocked with Dom Perignon, then proceeded to shake up the bottle and spray it all over each other like a fireman’s hose. I watched, aghast, as they jumped into the ocean with Rolexes still on their wrists. I opened my mouth to speak to the few natives who were left, and again, the response was the same: “You’ve got an accent,” they would say in a flat amazement.

Understand, then, when I sat down in Athens with Dimitra, meeting her face-to-face for the first time, after having translated pages and pages of her poems together via email for the past three years, that my translations were not a simple process. Understand that these translations would continue to inform my poems. I understood then and now more fully why I, in my poetry, translations, and life, am obsessed with setting and crossing boundaries. No emailing after five p.m., writing every morning, cross a boundary into Central American by myself. Return to a country that broke my heart, in so many ways, but like a steel umbilicus, will always remain attached to me.

Last spring, I was walking through UNL’s campus and heard a sound that was as familiar as a broken-in couch: two women were speaking loudly and unmistakably, in Greek. I summoned up my courage and struck up a conversation, mind you, in English. When they spoke to me in Greek, asking me basic questions, I froze, went silent, and answered in English. Suddenly, I was plagued by that familiar phrase: “You have an accent,” so rather than stumble into that moment of vulnerability, I went silent and then spoke in my literal mother’s tongue. During that moment, I felt a pull of longing that felt almost unnatural. So badly, I wanted to join their conversation. So much I wanted to just listen and eavesdrop all day. It is also worth noting, that whenever I am hurt or taken by surprise, I go silent. That feeling of helpless long for words was identical to that one I felt that day, wishing to join a conversation in a language that I once knew so well, but feeling my mind go blank. As I groped for the correct Greek words, I then realized how much I did not want to be looked at as a traitor, a freak, the moment I opened my mouth and my Midwest-drawl laced Greek would tumble out. I wanted to reunite with my language, then as I walked away realized, that in the middle of Lincoln Nebraska, I already had come back home. My translations and creative work were originated and produced here. That does not mean that I, as the ironically and seemingly fearless woman who crosses borders by herself, did not feel timorous. What I do also feel, though, is that translating my work and writing about my cultural disparity has allowed me to revisit my language and issues surrounding it. When I translate or when I write my own work, I am always uncomfortable; I am always crossing borders to reunite with language as though it is a lover. Nobody can keep my back; there is no conversation I cannot join.

Thinking consciously about both my translated and creative work has helped me to repair this sense of alienation. Ironically, in Lincoln Nebraska, where I certainly do not fit the mold of a native Nebraskan, I feel more at home within myself than ever, probably because I am self-aware, of how I do not fit, and because of this conscious disparity, have managed to fit in and find a home. What has ultimately happened, as a result of this work, is that I have become truer to myself in every capacity. I have also become truer to my boundaries and kinder in how I articulate them. In other words, my boundaries have come home, and they are comfortable, I no longer feel the need to put myself in potentially life-threatening situations or escape to crazy places, or to feel uneasy. There is no longer a need; I am home.

An excerpt from my craft and travel memoir, “The Blue Hole”

The Blue Hole as an Incant Against Depression

As I pack my bags, I make a madwoman's promise: to live or die trying. This sack of flesh was barely a 34-year-old, puffy-eyed, sunken-cheeked woman. I'd given to Will on my own volition, and he'd never lied about his commitment. I'd given to students, the academy, to the Ph.D. program. There was nothing left. My eyes had become islands. My spirit, once unbreakable even amid the self-created drama, had grown distant as my eyes. I promised to trek alone, in hopes of getting something unspeakable back. Belize was supposed to be beautiful. Somewhere, off in the middle of the ocean stood that stunning blue-black hole. I wanted to see that, to see everything except myself.

When I arrive at the dilapidated hostel, a young Mexican man is twirling fire. During my first evening, alone, everywhere I look and go, pairs remind me of my brokenness. Pairs of glistening silverfish underwaters. Pairs of suntanned couples caressing each other's faces across the table. Pairs of faces reflected in my wine glass as I ate and drank alone. Pairs of socks, stars, colonizing in the sky. My identity is defined by haves and have-nots, I sit at the restaurant table and listen to reggae lyrics about love being a religion, drain my drink, and have another. Shirtless college kids do shots. My decision is made: I need to make friends, preferably with someone at my hostel, for convenience.

That next afternoon, I follow a few straggly Australians to a corner of the beach where the natives hung out. The tide is out, the sun is hot, and men play cards on tree stumps. The guys kept calling me Pamela Anderson, an ironic nickname due to my B-cups. I take a seat at the tree stump while the Australian guys go swimming.

We drink sugary rum-and-cokes. Twenty minutes later, euphoria wraps around me. I want to braid your hair, says a local woman. She had an orange tank top on, a gold front tooth, and rows of beautiful braids. Her fingers felt soft on my scalp.

By then, the sun is high, and the tide is creeping in. More people pour into the beach; the guys from the hostel were gone. A husky man shows up, covered in tattoos. He was bigger and bulkier than the other natives, with a fleshy stomach, pockmarked face, crop of black curly hair, and the saddest eyes I’d ever seen. He was barefoot and shirtless, like most of the guys on Caye Caulker. He hates my guts immediately, which gives me all the more reason to make him like me. This trait is my disease and talent. Call it a pathology or just fucked, but as my failed relationship dictates, pursuing ambivalent people is my talent. The fact that this angry, burly stranger hated my guts made me, high as Mount Everest on coke, determined to make him my friend.

You’re thirty-four, he said coolly. I can tell, but I bet nobody’s going to tell you that.

I look into his sad eyes. And you’ve got lipstick all over your mouth. I bet nobody’s going to tell you that either, he says. Instinctively, I reach out, and dab, my lipstick, which has smeared around my mouth. I ask him why he's such a dick, fueled by coke and rum. His tight curls look Bo-Peep-esque spiraling around those large eyes. By then, the tide has risen to our ankles. Suddenly, where there were people playing cards, there’s only water. I tell him to quit being mean and scary.

When you're grieving, time is taffy. I befriend Ruddy, and although he made it clear that he wanted to steal my cell phone, he turned out to be good company and a nice person. For two days, I sit in Rudy's filthy, tiny tattoo parlor and tell this man everything I feel. He becomes pushy, telling me to go for a rum run with him. I tell him no: I’m sensitive to light and strung-out. Please, come with me, he says, and it’s more of a demand. I say no, thanks. He keeps asking me.

I sit up. Listen, I say, if there’s one thing that I cannot stand, it's when someone bosses me around. I just said no, dude. If this is a contest to see who's more stubborn and more likely to get her way, then I win, all right?

He leaves. I sit on his sad little balcony. It feels good to be mad; it’s better than numbness. When he comes back, we drink more rum. By now, my heart races, my skin feels as though lacquered beetles skitter across them. We sit across from each other on the floor and drank the rum. The day had morphed into the afternoon, our second day together. I tell him about Will. He tells me about growing up in Phoenix. I was a little nerd, he explains. They put me in the special ed classes. I wore glasses. I could hardly talk. They thought I was dumb and made fun of me. He pauses as speaking to the ghost of that same, broken boy. And yes, he says, my glasses were broken and taped in the middle. He lets me feel the bullet buried in his forearm. For the first time in a long time, I cry about everything and tell him I feel a rupture within myself. He sits and listens, letting me feel the bullet, says nothing.

He tells me how he learned to gang-bang how that taught him to be smooth. An older boy took him in, so Ruddy was no longer a little nerd. Eventually, he and his mentor would go on weed runs together. Ruddy describes the older boy who, on a drug run, pulled out his pistol and whacked a guy on the head. From there, his life unfurled itself into a rap sheet of arrests for everything from dealing with assaulting before he finally decided to return to Belize with his family.

Aerial View of the Blue Hole

Fly over it, and it looks like everything and nothing. When divers try to descend into its impossible depths, they are disappointed to find nothing, and then more nothing. I ask Ruddy about the Blue Hole; he tells me people are let down. From a helicopter view, however, the hole is majestic, but once divers descend into its depths, they surface in frustration; there is nothing there but dark.

He talks about Kriol, that lilting language passed down by his ancestors, the language of slaves. And I understand what I could not, that there are worlds that coked-out white girls cannot and should not attempt to explain; worlds a white girl, alone, with a backpack and a break-up, can't cross into, wounds too deep to ever stitch. That woman can only tell her own story.

At some point, he asks me to marry him. Why not? I reason. My life fell apart because I spent six years chasing a fifty-three-year-old beach bum. Why not marry Ruddy? Weirder things have happened. But instead, I explain that I have comprehensive exams to work on, students to teach, and a life to return to. I can’t get married.

He insists that he has dual citizenship, so he can easily move to Lincoln. I counter that with his past criminal record, he’ll have a hard time finding a job. Still, he says he loves me. Again, I consider his offer. Yes, he’s a petty sociopath, but at the same time, but didn’t weirder things happen? Stupid women born into privilege and overwork chase older available men. People tell her constantly what she can and cannot do, including men, particularly those who dictated her life. By that logic, Ruddy and I might stand a chance.

My concern is that he seems like a dangerous person, which I express, to which he agrees with an endearing shyness. He tells me that his preferred crime is robbery. He says that although he doesn’t mind killing people, he really likes to rob them. He says this with such joy: robbery, it's what he really likes to do! To me, theft had always been an act of desperation, not pleasure, yet his excitement is undeniable. He thinks I ought to meet his mother, who is a feminist, too, who hates men like me, with whom I’d get along famously.

I express my reservations that his mother will not appreciate meeting a drunk white woman, which he reassures me his mother is an alcoholic, so it will probably be fine. My heart races, paranoia rushes over me, and a migraine forces me into his tattoo recliner. Ruddy spends the evening feeding me Ramen, offers to go to the hospital, and mops my brow with a towel. I awaken, bathed in sweat with him snoring into my ear, I put on my shorts and slip out his back door.

But this is, after all, our world. A woman wakes up after a coke-bender with a stranger she considered marrying, whom she decided to love, if only for a minute. This world is where madmen rule our psyches, and madwomen take over their own, so we cross borders between excess and sanity. Angels are thugs who let you feel the bullets in their arm, thugs become your medicine men, your ex-love fades into a ghost, and the devil wears blue jeans and has blue eyes. Perhaps there is no right or wrong; just blurred boundaries between our lonely narratives. I’m not sure why Ruddy elected to be so kind: but he was.

My body, which I had forgotten until recently, was wracked with hunger. Weakened by the lack of food except for Ramen, I go back to the hostel and sink into a slumber for an entire day. As I lay down, I wonder whether I should leave the island and cross the border or fly over The Blue Hole, both all of which terrify me. The world wants women to be scared. Yes, I am afraid but tired of that feeling. Look under your car. Don't travel alone. Use better judgment. Don't cross the border. Don't go to Belize. As my mother once said when I was thirteen, barely grazing the periphery of puberty, while we were walking down the dark streets of the formidable, gay island of Mykonos, don’t look too pretty.

Careful for the border, everyone said. Careful crossing, always look back, always look behind you on dark streets. A part of me felt numb. A part of me felt relieved. A part of me felt devastated. And a part of me felt stronger. I was on my own, a prospect that I feared. How many times had my female friends confirmed this fear, said that I was a mess, and reminded me of how lucky I was to be with Will?

How many times had I lied to them, or glossed over the stories of our fights, making excuses, implicating myself? He'd stormed out of restaurants all those times and left me there, alone, while I conveniently omitted those revelations. Use better judgment: I had until now. Attending graduate school on a full-ride, becoming the darling of the doctoral program, winning the awards, receiving positive student evaluations, until a long list of missteps, I'd finally done mostly everything right, and look where it had gotten me. I was tired of being scared. I begin to consider crossing the border by myself.

The Blue Hole as a Self-Guiding Compass

That night will be my last on the island. There’s no need to fly over that beautiful, blue structure as the helicopter ride is out of my price range. I sit alone on the beach outside of a reggae bar, until a guy sits next to me. His name is John. He is 25. A combat veteran from Denver, and radiates sweetness. There’s also brokenness behind his eyes, and once we get closer, the cracks become visible. As we sit on the dock, we discuss our travel plans: tomorrow; he is going to San Ignacio.

He tells me about serving in the frontlines of Afghanistan, how he is traveling because he wants to be a kid again. He tells me how he’s been blown up, and awakened fifteen days later in a hospital with a shattered hip. He’s received an honorable discharge and begins community college in the fall. We discuss the prospect of taking a ferry tomorrow to San Ignacio. We gravitate toward each other the way travelers do: two opposite spheres with nothing in common in the world, except the world itself—both of us crossing painful borders to leave our brokenness behind.

John asks me who I think he is that first night as we lay together in his hammock. I’ve taken the best shower of my life, the first one in a while. You’re twenty-five, I say, turning to look at him: a slender blond, rust-colored fuzz running down his abdomen, and those eyes, blue and broken as a fallen robin’s egg. I tell him he's been through a lot, has a tortured side, and seems to bury his intelligence.

He says he doesn’t feel the need to prove his intelligence to people. That evening, we drink Gatorade and vodkas, lying together in the hammock on the balcony. He tells me he’s missing something after the war, ever since he’d been hospitalized, his hip shattered with shrapnel embedded in his thigh, he still hungers to replicate that adrenaline. He’s wrecked a brand-new motorcycle swerving in and out of three-lane traffic, and get into fistfights in bars with miraculously no arrests or bruises. Before the war, he'd lost both of his older brothers to heroin overdoses. He's never done any drugs heavier than weed, wants to be a kid again, but feels himself plunging deeper, as he called it, into that adrenaline gap. He hopes that registering for community college will pull him out, but doesn’t know what he wants to do in life.

I tell him I didn’t know what I wanted to do until I was thirty-two. As we lay there together, he tenderly opens my hand. Something within me, a blue bloom, clenched like a fist, painfully reopens. Blue. It’s the color of animal sexuality, beast’s blood, a woman gone cold to the touch. It’s the color of lips on a bloated body. It’s the sound of sadness and hunger, and the color of nothing. I desire to cross the border. San Ignacio is about twelve hours away from Guatemala. I can barely make it, with about a week of travel left.

The following day John, I go to Xunatunich, the Mayan ruins. As we hike in the unforgiving heat, John tells me how his PTSD flares up when he’s surrounded by dust. When we reach the ruins, the heat no longer matters.

There was a football field-sized green grass. We sit in silence at the top, staring out at the green geometry, the worn rubble, our legs pressed together—a dark arc of a spider monkey swings from branch to branch. Below us, two men; one in a dashiki, one with dreadlocks piled on his head, as if they’d rehearsed, flip toward each other, head over hands. They begin running through the ruins, racing, and commenting on the energy; they are also American. The breeze cools to balmy, and a voice says, it’s all going to be fine. And another voice says, you’ve got to keep going.

That morning, John and I parted ways over breakfast. I tell him I need to cross the border. He says that’s out of his way, that he’ll go to San Pedro instead. Across the table, his eyes harden and freeze like mid-March ice. The boy I’d lain beside on the hammock who touched the skin of my wrist is gone. His eyes trained on me like firing squads.

At that moment, I see the killer he’d been in his past life. I told him that I was nervous about crossing the border, of the rumors of hassle and danger. He said that’s natural. We hug briefly, then part ways. A deep sense of emptiness overtakes me. I want to hide inside him and never return. Later on, I will relate this to my therapist, and she will become tearful, tell me that PTSD causes people to shut down. I know what she means.

On the overnight bus to Guatemala, I felt flayed and tender. Who was I to think a twenty-five-year-old kid would hold interest in me? Why did I fall into people and lose myself? As I stretch out to sleep, another memory of Will arises. One time, he rose his hand as if to hit me and said, how would you like that? I wonder what the context is, which I can’t remember. I had been joking, and he'd grown angry and raised his hand. After an uneasy sleep, I awaken in Guatemala.

Blue Hole as a Drunk Doppelganger Who has Exactly Three Hours to Catch the Bus to Cross the Border

That morning, the bus let us off at a dusty stop. As I wait for the border shuttle, I receive an email from Ted, checking to see how I am. As we drew close to the demarcation between Belize and Guatemala, my two selves collide. There is the person back home who has a big, now-empty apartment, a friend who was a former U.S. Poet Laureate, a reliable candidate, yet like a feral cat, knew how to hide her wounds.

Then, there is this Maria: an open wound, a sea of bitterness like my name, an empty blue hole that contains everything and nothing: the Maria covered in sand flea bites whose nasal cavities still dripped with coke, who contemplated marrying a sociopathic felon. I began to laugh. The latter version was far more likable. At least she was authentic.

At the border, a boy with a bowl-shaped haircut walks with me. At that point, rumors about tensions between Belize and Guatemala jumble in my head. I take his hand. The horizon looks like the set of an old Western, a dusty line of stores, as though they'd collapse with one poke. As I walk with the boy, who speaks perfect English, men with white vans keep offering to drive me through the border crossing.

It’s the only way, they say. Eighty dollars. No, I respond. Eighty is too much. But it's the only way; the men say—the boy nods. I don’t think that’s right, I say. I keep denying and negotiating at every step. Finally, as we reach the entrance, the boy apologizes. That's not the only way. They were hustling you, but I couldn't say anything, or they'd be mad. I tell him that it is perfectly fine; we do what we need to get by. The boy walks me across the border. I tip him well.

When I arrive in Tikàl, I am heartened by little cobblestone streets, bougainvillea dribbling down the walls, a lake at my hotel window. I spent the evening drinking boxed wine with a barefoot Australian. We sit on our hotel balcony, and he tells me how he’s backpacked for the past year by himself. There’s a woman in Panama he’s taken acid with and fallen in love; he tells me how they’d found a series of seemingly never-ending sand shelves.

Throughout the night, they’d stayed up, talked, and climbed each shelf. He says he wants to see her again. When I ask why he doesn’t text her to make plans, he shrugs. What are you so afraid of? I ask. He says he’d rather wait it out and see if the universe will rearrange itself for him – or not. Maybe there is something to not forcing people to love you, I think to myself. With Will, I felt as though I was shoving a popsicle into the mouth of a choking diabetic.

From Tikàl, I go to Antigua, check into a hostel run by three bawdy Australian expatriates. In my spare time, I google Ruddy, whose actual name is Jared. A few years ago, he’d been accused, though not convicted, of biting a thirteen-year-old girl on the neck in a playground. Sickness spills over me. The poor girl had been so frantic that the court could not piece her story together. I remember a moment I'd forgotten: in his tattoo studio; he'd wanted to give me a hickey and nipped my neck. I'd said no.

He'd tried, again, anyway. I said no, do you understand me? Don't fucking bite my fucking neck, motherfucker. No means no. He’d stopped. There had been other times, too, during the bender: he’d tried to push himself on top of me, and I’d said, motherfucker, no, don’t you dare, and he’d stopped. That poor child was a victim who, like so many others, will go unheard. I wonder what saves and separates me from her fate, other than a few decades. I don't pray, but I thank my mouth and luck that plucked me from that fate, and that poor kid from a worse one.

I call a patient friend, angry. You didn’t know, he responds. Start putting on some sunscreen and get yourself in a better place. And so, I begin putting on sunscreen. I have a few days left, so I drink at the hostel bar with the Australian owners. One of the guys was pale and bald as a cue ball, his crown anointed with a wound from when he'd been jumped. I spend time at the bar and walking around the city, candy-colored buildings, a little town outside where you could buy sugar cookies, and a chocolate factory a family operates out of their home.

I review the long list of things I can do differently. Images abound of being bitten on the neck, of Will raising his hand to me, of another time when he shoved me, litter around me like mosaic shards. I'd forgive my flaws and value my life. I was lucky to be here and swore never again fall into somebody so deeply that I’d lose myself.

That next day is my final one. I have to take the overnight bus back across the border, and then fly out of Belize. My bus leaves at three; it is eleven AM. I dread going home to that empty apartment. That morning, the pale Australian guy keeps buying me more beers. American girls can’t drink, he said. The fuck we can’t, I respond. I’ve been training this whole vacation.

We find ourselves in an Irish pub overrun by Australians. An Irish rock band plays. American girls can’t drink, says the Aussie. Fuck that, I say. My bus leaves in four hours, and I'll drink your ass under the table. By now, it is noon. The guys chug beers and drop into plank poses, while their girlfriends cheer them on and take pictures. This lightness is what makes tourists set their backpacks down, leave their lives behind, become expatriates. My program will begin in the fall. I can either go back or not. I can start an entirely new life, reinvent myself or disappear, a quality I love about those who transplant to different countries. I know how to do this; I’ve done it so many times.

Across the bar, a long-haired man in a rumpled, white shirt catches my eye. Let’s dance, he says. As we whirl around the pub, the only ones who are dancing, he pulls me close; you don't belong here. You’re not loud and drunk. But I am, I protest. Maybe I just show it differently. I've got a bus to catch; I tell him as if he cares. He pulls me in and whispers, I’ll bet you don’t leave. He smells like hickory and soap. You’re going to miss your bus. Everything comes back in flashes: a raised hand, a sad-eyed man telling me he likes to rob people, a man with hardened blue eyes, a woman throwing her clothes into garbage bags in the middle of the night, sitting on her couch, straddling the blue void in between living in dying. All I could think was, I choose to live.

And as we spin like tipsy marionettes, I realized something else: it was I who applied to graduate programs on my own despite my editor’s advising against it, it was I rented a cottage when I first moved in with Will—something we’d conveniently forgotten—then subleased to make extra money. I had been the one to walk away, who, after being accepted to the program, melted down my gold jewelry for gas money to drive, alone, with two cats across the country. I'd lived in my body, even after it began to break. Good choices and bad, I had co-created my life—and not all of it is terrible, and for the first time, I don’t wish to run into someone, or away from anything.

I tenderly touch the stranger’s face and walk out the door. In this moment, greeted by the harsh sun, I am leaving: ready to cross over to a place far from perfect, but alive and authentic.