Howard Andrew Jones's Blog, page 41

August 28, 2015

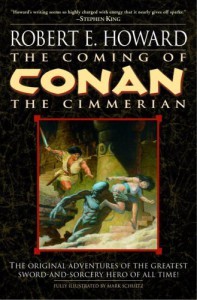

The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “The Tower of the Elephant”

Bill Ward and I are working our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing story four, “The Tower of the Elephant.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are working our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing story four, “The Tower of the Elephant.” We hope you’ll join in!

Howard: If you listen very closely, toward the end of the final verse of The Beatles hit “Hey Jude” you can hear either Lennon or McCartney (stories vary) shout out in surprise “Whoa!” followed a moment later by “f*ing Hell!” Once you notice it, you can never NOT hear it, a single small ding in an otherwise flawless song. I feel the same way about Robert E. Howard’s use of the word “frostily” or “frosty” in “The Tower of the Elephant.” I didn’t notice it the first four or five times I read the tale. Now I can’t ever NOT see that he uses it maybe two times too many.

And damned if that tiny nitpick isn’t the only thing I can find remotely wrong with this story. THIS is Robert E. Howard at his absolute best, in complete control of his narrative, knowing his character better than his closest friend. His Hyborian history article was written just prior to his penning of “The Tower of the Elephant,” which makes sense, because he knows the history and societies so well that he casually mentions cultures in such a way we can usually intuit what he’s talking about.

And damned if that tiny nitpick isn’t the only thing I can find remotely wrong with this story. THIS is Robert E. Howard at his absolute best, in complete control of his narrative, knowing his character better than his closest friend. His Hyborian history article was written just prior to his penning of “The Tower of the Elephant,” which makes sense, because he knows the history and societies so well that he casually mentions cultures in such a way we can usually intuit what he’s talking about.

Bill: Yes, you can really see him drawing on some of that background he had just worked out in this story, both in the cosmopolitan setting, and in the bit of “deep history” he gives us in the words of the Elephant God toward the story’s close.

Howard: Yeah — now I’m glad you insisted we read that essay first.

I love the opening of this story. I keep comparing Robert E. Howard’s description to camera work, because he often uses an establishing shot. His words present the hustle and bustle and atmosphere of both the section of the city and the tavern itself.

I love the opening of this story. I keep comparing Robert E. Howard’s description to camera work, because he often uses an establishing shot. His words present the hustle and bustle and atmosphere of both the section of the city and the tavern itself.

And then Conan appears. We, the readers, know well who he is, even though he’s not mentioned by name, and he clearly dominates the scene. And, true master that he is, REH continues to give us great throw away lines that are incredibly revealing of character: “The Cimmerian glared about, embarrassed at the roar of mocking laughter that greeted this remark. He saw no particular humor in it, and was too new to civilization to understand its discourtesies. Civilized men are more discourteous than savages because they know they can be impolite without having their skulls split, as a general thing.”

Bill: Here Conan is a “gray wolf among gutter rats,” to paraphrase just one of the great lines in the opener. From the first paragraph of this section that paints a vivid picture of The Maul, the thieves district of Zamora where the guards have been bribed with “stained coins” to leave the criminals alone, all the way to the conclusion, which sees Conan slay the civilized man who just didn’t understand that you can only push some men — literally in this case — so far. I think this opener, and this story in general, is one of the best introductions to Conan, and probably the one I would hand a novice that was interested in seeing what all the fuss is about.

Howard: Me too — this is usually where I tell people to start. A great story like this is chock full of one fine scene after another, and we next get Conan’s take on civilized religion, then join him for his foray into the grounds of the Tower of the Elephant. The action is fluid and surprising and exciting. The meeting with Taurus and the thief’s astonishment at his daring is perfect. At first it seems like Conan is outclassed, but then he lengthens the thief’s life by slaying that lion, impressing both him and the readers at the same time.

Howard: Me too — this is usually where I tell people to start. A great story like this is chock full of one fine scene after another, and we next get Conan’s take on civilized religion, then join him for his foray into the grounds of the Tower of the Elephant. The action is fluid and surprising and exciting. The meeting with Taurus and the thief’s astonishment at his daring is perfect. At first it seems like Conan is outclassed, but then he lengthens the thief’s life by slaying that lion, impressing both him and the readers at the same time.

Bill: It’s Conan’s savage instincts that ultimately prove to be of greater worth than Taurus’ long experience. Even a Prince of Thieves — a man with a poison gas blowgun, super-rope, and a strangler’s grip — doesn’t have eyes in the back of his head like a barbarian who has lived by his wits in wild places. And the whole interaction between the two is really finely put together, just trying to imagine the story without Taurus results in something lesser. As amazing as Taurus is, it’s Conan that, as you say, we ultimately become even more impressed with, and that’s only because we have Taurus to compare him to.

Howard: Right on all counts. Taurus allows us to better understand how impressive Conan is, and I can’t imagine the story being as enjoyable without him. The tower itself is gorgeous. I still wonder what Taurus planned when he told Conan to remain behind, the characters being so well motivated that I don’t find myself asking what REH intended, but what his character was thinking. Hocking and I were talking about it the other week and we were both wondering whether or not Taurus was going to betray Conan, or if he actually had something in mind for him to do.

Howard: Right on all counts. Taurus allows us to better understand how impressive Conan is, and I can’t imagine the story being as enjoyable without him. The tower itself is gorgeous. I still wonder what Taurus planned when he told Conan to remain behind, the characters being so well motivated that I don’t find myself asking what REH intended, but what his character was thinking. Hocking and I were talking about it the other week and we were both wondering whether or not Taurus was going to betray Conan, or if he actually had something in mind for him to do.

Bill: Right, I’m not sure either. Taurus has already established he knows a good deal that Conan does not, not just of thievery in general (the discussion about why you would leave a dead guard’s body out rather than hide it was a small slice of brilliance) but of the Tower in particular. So, when he dashes ahead of Conan there is enough doubt established to suggest that maybe he really is working in both their interests. I would suggest, though, that in every other instance of Conan’s instincts in this story Conan is reacting accurately, he does not “doubt his senses” even when confronted with the impossibility of the Elephant God himself, as a civilized man would. And Conan’s initial reaction to Taurus’s entering the tower while Conan does a possibly needless bit of scouting was to distrust the Nemedian’s intentions.

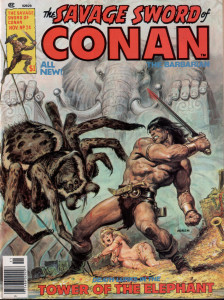

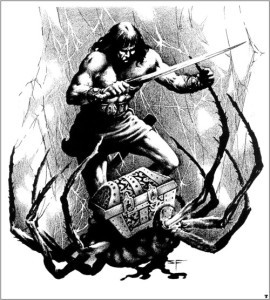

Howard: And damn, there are giant spider fights, and then there’s the fight with the thing in the top room of the tower. The only giant spider fight I’ve read that’s on the same level is the one from the first Bard book by Keith Taylor. You can see this monster and its dripping venom, so virulent that it scars Conan for life. And it’s not just a swing and a miss and a squish, that dammed thing stalks him and scuttles across the ceiling. It’s just incredibly well written, so much so that even after reading this story multiple times I still find it thrilling. And unsettling.

Howard: And damn, there are giant spider fights, and then there’s the fight with the thing in the top room of the tower. The only giant spider fight I’ve read that’s on the same level is the one from the first Bard book by Keith Taylor. You can see this monster and its dripping venom, so virulent that it scars Conan for life. And it’s not just a swing and a miss and a squish, that dammed thing stalks him and scuttles across the ceiling. It’s just incredibly well written, so much so that even after reading this story multiple times I still find it thrilling. And unsettling.

Bill: The fight is great, and it’s also interesting how clever the spider is — the move it used to bind Conan’s ankle was very slick. Really, the only things that come close to killing Conan in this story are creatures operating at an even more instinctual level than himself.

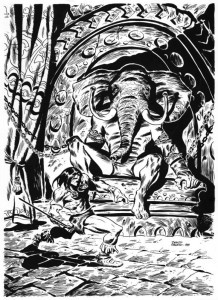

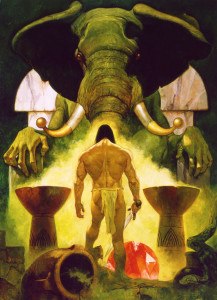

Howard: Right! Finally we arrive at the big reveal, with one of my favorite moments not just from Robert E. Howard or his Conan stories, but all adventure fiction, when Conan comes upon the crippled creature:

“…and Conan’s gaze strayed to the limbs stretched on the marble couch. And he knew the monster would not rise to attack him. He knew the marks of the rack, and the searing brand of the flame, and tough-souled as he was, he stood aghast at the ruined deformities which his reason told him had once been limbs as comely as his own. And suddenly all fear and repulsion went from him, to be replaced by a great pity. What this monster was, Conan could not know, but the evidences of its sufferings were so terrible and pathetic that a strange aching sadness came over the Cimmerian, he knew not why. He only felt that he was looking upon a cosmic tragedy, and he shrank with shame, as if the guilt of a whole race were laid upon him.”

“…and Conan’s gaze strayed to the limbs stretched on the marble couch. And he knew the monster would not rise to attack him. He knew the marks of the rack, and the searing brand of the flame, and tough-souled as he was, he stood aghast at the ruined deformities which his reason told him had once been limbs as comely as his own. And suddenly all fear and repulsion went from him, to be replaced by a great pity. What this monster was, Conan could not know, but the evidences of its sufferings were so terrible and pathetic that a strange aching sadness came over the Cimmerian, he knew not why. He only felt that he was looking upon a cosmic tragedy, and he shrank with shame, as if the guilt of a whole race were laid upon him.”

It was a habit of the times to give villain’s monologues, or to explain plot points through sages. We’ve seen that already in some Leiber, most especially the dreadful “Adept’s Gambit” and we’ve seen a little of it in preceding Conan stories. We’ll see it in some written after. But THIS monologue is so nicely done that it flows naturally, and the moment is so riveting that we can imagine Conan standing, nearly spellbound, considering it.

Bill: And the cosmic stranger’s plight is the strongest condemnation of civilization in the story, going right back to that theme that was there from the start. The vile man who has tortured the creature for its secrets is not described as a magician or sorcerer, but a priest — in the fact the High Priest of the city, a man whom the ruler of Zamora fears and obeys. A barbarian thief might cut your throat, but he won’t enslave and torture you for centuries to get at forbidden knowledge. The tower that is the Elephant God’s prison was built with his own stolen power, a very constructive, civilized use of such magic. In the end, it’s a fellow-outsider who does not flinch away from the impossible visitor from the planet Yag, who clearly sees the misuse the creature has been put to, and who kills it for the sake of mercy and of vengeance. It did occur to me that Conan’s obeying of the Elephant God’s final wishes may be due to some geas laid on the Cimmerian, his revulsion and sense of justice possibly not being enough of a motivation to risk everything to confront the priest. I suppose, at that point, Conan’s only way out was to do as the creature bade him, so it isn’t as if he had any real options, anyway.

Bill: And the cosmic stranger’s plight is the strongest condemnation of civilization in the story, going right back to that theme that was there from the start. The vile man who has tortured the creature for its secrets is not described as a magician or sorcerer, but a priest — in the fact the High Priest of the city, a man whom the ruler of Zamora fears and obeys. A barbarian thief might cut your throat, but he won’t enslave and torture you for centuries to get at forbidden knowledge. The tower that is the Elephant God’s prison was built with his own stolen power, a very constructive, civilized use of such magic. In the end, it’s a fellow-outsider who does not flinch away from the impossible visitor from the planet Yag, who clearly sees the misuse the creature has been put to, and who kills it for the sake of mercy and of vengeance. It did occur to me that Conan’s obeying of the Elephant God’s final wishes may be due to some geas laid on the Cimmerian, his revulsion and sense of justice possibly not being enough of a motivation to risk everything to confront the priest. I suppose, at that point, Conan’s only way out was to do as the creature bade him, so it isn’t as if he had any real options, anyway.

Howard: Oh, I’m pretty sure he does it out of choice, that he senses the truth of what the creature has told him. I think at least that’s what REH is wanting us to think. We, the reader, are just as convinced as Conan has been.

Howard: Oh, I’m pretty sure he does it out of choice, that he senses the truth of what the creature has told him. I think at least that’s what REH is wanting us to think. We, the reader, are just as convinced as Conan has been.

Bill: As am I, really, there’s just that one line, about it not even occurring to Conan not to follow instructions, that had me thinking that maybe there’s a small case to be made for the Elephant God pulling a few strings, but it’s certainly more subtle (subtle to the point that it’s probably solely in my imagination) than anything in “Frost-Giant’s Daughter.” I like that that ambiguity can crop up though, even if it isn’t intended at all, because REH isn’t beating the reader over the head by telegraphing Conan’s intentions. It says something that a penniless wanderer would forego a priceless treasure in order to avenge a monstrous crime — a crime against a creature far more alien than any lion, spider, or civilized man.

Howard: Yeah. There’s a certain elemental decency about Conan that gets overlooked, or exaggerated.

Bill Overall, this is a story that does everything right, and does it masterfully. Conan is the man we will come to know in future tales, the Hyborian landscape has been delineated in a way that deftly integrates it into the story, and the action and imagination hooks the reader and carries them right along to the finish. It seems pretty simple, too, until you go back and look at how the pieces fit together — and then you realize it only seems simple because it was crafted with an expert hand. It’s one of the best of the best, and its no surprise that “The Tower of the Elephant” is a perennial fan favorite.

Bill Overall, this is a story that does everything right, and does it masterfully. Conan is the man we will come to know in future tales, the Hyborian landscape has been delineated in a way that deftly integrates it into the story, and the action and imagination hooks the reader and carries them right along to the finish. It seems pretty simple, too, until you go back and look at how the pieces fit together — and then you realize it only seems simple because it was crafted with an expert hand. It’s one of the best of the best, and its no surprise that “The Tower of the Elephant” is a perennial fan favorite.

Howard: It’s certainly one of mine. But then I’m a fan. Next week, join us for a journey to “The Scarlet Citadel.”

August 26, 2015

Robert E. Howard Article-a-Thon

With me in the midst of about four different projects in four different stages, I’m keeping things short today and pointing visitors to some previous REH essays they might not have seen.

With me in the midst of about four different projects in four different stages, I’m keeping things short today and pointing visitors to some previous REH essays they might not have seen.

First, why Conan and the Emerald Lotus is my favorite Conan pastiche, with the possible exception of Conan and the Living Plague.

Second, an overview of the better Conan pastiches, filtered through my own sensibilities.

Third, comparing the sexism in Vance to that in Robert E. Howard’s work.

Fourth, an article I didn’t realize was so old! (Maybe I am.) It celebrates Robert E. Howard’s birthday.

Fifth, Under the Hood with Robert E. Howard.

Sixth, some thoughts on Robert E. Howard’s action writing chops.

Lastly, I tracked down that great Leo Grin essay on the perfect Conan collection. Up at the top it makes reference to some controversies and debates some readers might not be familiar with, but I think the general REH fan should keep reading to the bottom to get to the sections on how an ideal collection could be organized.

August 24, 2015

Hex Crawl Chronicles

From time to time I talk about world building on this site. I think any writer has to give an awful lot of thought to world building, i.e. presenting a setting that’s not just consistent and logical but interesting.

From time to time I talk about world building on this site. I think any writer has to give an awful lot of thought to world building, i.e. presenting a setting that’s not just consistent and logical but interesting.

One of the reasons setting books appeal to me so much is that a good one just drips with ideas, and can be chock full of world building inspiration both for writers and gamers. I’ve discussed other great settings, but I’m overdue discussing the Hex Crawl Chronicles written by John Stater.

All of the Hex Crawl Chronicles have cool stuff in them, but several are so rich with atmosphere that the adventure ideas within just about beg to be played.

All of the Hex Crawl Chronicles have cool stuff in them, but several are so rich with atmosphere that the adventure ideas within just about beg to be played.

(Throughout this article I’m posting links, via product images, to other fine hex crawl products.)

If you’re not familiar with a hex crawl, it’s a game setting where a vast area of land and water is overlaid with hexes, and then any number of hexes are populated with people or creatures or settlements or ruins or what have you.

Rather than being an adventure with a start and end point plotted out, a hex crawl is a setting with a whole bunch of interesting places and events and people already in place, and the player characters are free to wander in and play with it all.

At least, that’s the theory. Unfortunately, a lot of hex crawls can end up pretty dull. For instance: “Hex 1001: 3 goblins.” There are several good hex crawls out there, but truly excellent ones are hard to come by. Three of my favorites are in Stater’s Hex Crawl Classics line.

At least, that’s the theory. Unfortunately, a lot of hex crawls can end up pretty dull. For instance: “Hex 1001: 3 goblins.” There are several good hex crawls out there, but truly excellent ones are hard to come by. Three of my favorites are in Stater’s Hex Crawl Classics line.

The first is The Winter Woods (Hex Crawl Chronicles 2), a wilderness region where an ancient entity plots to bury the region in ice and snow. I know, I know, you’re probably thinking that as the author of The Bones of the Old Ones I’d naturally find that of interest, but that’s just a background plot that you can use or discard as you will. It provides connective threads, however, that help set other events in motion. There are colorful characters to meet, interesting challenges and destinations, weird adversaries, and even the potentially mundane is rendered interesting by Stater’s write ups.

The first is The Winter Woods (Hex Crawl Chronicles 2), a wilderness region where an ancient entity plots to bury the region in ice and snow. I know, I know, you’re probably thinking that as the author of The Bones of the Old Ones I’d naturally find that of interest, but that’s just a background plot that you can use or discard as you will. It provides connective threads, however, that help set other events in motion. There are colorful characters to meet, interesting challenges and destinations, weird adversaries, and even the potentially mundane is rendered interesting by Stater’s write ups.

The Winter Woods is more of a “normal” fantasy setting, meaning that the area’s wide open for exploration with a few settlements and a whole lot of wilderness. But when I say “normal” I don’t mean boring, because most “normal” settings just aren’t even half as evocative or inspiring. When I read The Winter Woods, I smiled with joy and was immediately inspired.

The Winter Woods is more of a “normal” fantasy setting, meaning that the area’s wide open for exploration with a few settlements and a whole lot of wilderness. But when I say “normal” I don’t mean boring, because most “normal” settings just aren’t even half as evocative or inspiring. When I read The Winter Woods, I smiled with joy and was immediately inspired.

The same can be said about my reaction to the other Hex Crawl Cronicles, particularly the next two, which I enjoyed just as much as The Winter Woods.

The Shattered Empire (Hex Crawl Chronicles 4) has an entirely different feel from The Winter Woods. Here is a region fragmented by war. Three major factions are vying for control of the area, and characters can wander on scene and aid any one of them, or even minor factions, or simply try to take advantage of the chaos, or do some exploring of their own in the ruins and wilderness, with all the mayhem as a backdrop and obstacle. There are any variety of ways that the characters can intervene and change the course of history. It just begs to be played.

The Shattered Empire (Hex Crawl Chronicles 4) has an entirely different feel from The Winter Woods. Here is a region fragmented by war. Three major factions are vying for control of the area, and characters can wander on scene and aid any one of them, or even minor factions, or simply try to take advantage of the chaos, or do some exploring of their own in the ruins and wilderness, with all the mayhem as a backdrop and obstacle. There are any variety of ways that the characters can intervene and change the course of history. It just begs to be played.

Lastly, there’s the inspiringly weird Beyond the Black River (Hex Crawl Chronicles 3), a twilight realm where petty deaths compete for the souls of men and women, where strange human cultures eke out a living, where blood-curdling creatures prowl the never-ending night and a full moon rises in place of the sun. Sometimes “weird” means full-out gonzo or nonsensical, but this is quite simply so cool I wish I’d come up with it so I could write stories there.

Lastly, there’s the inspiringly weird Beyond the Black River (Hex Crawl Chronicles 3), a twilight realm where petty deaths compete for the souls of men and women, where strange human cultures eke out a living, where blood-curdling creatures prowl the never-ending night and a full moon rises in place of the sun. Sometimes “weird” means full-out gonzo or nonsensical, but this is quite simply so cool I wish I’d come up with it so I could write stories there.

Go take a look. Even if you never plan on gaming them I bet you’ll find them a fun read, and they might just inspire some story ideas of your own.

(Both Sine Nomine — here and here — and New Big Dragon Games have wonderful booklets for helping you set up your own hex crawls, not to mention some other really cool stuff. Most Sine Nomine material has wonderful hex crawl mechanics for its setting, although Red Tide and An Echo, Resounding are a good start point, and for New Big Dragon, you want both the Sandbox Companion and DM Companion.)

August 21, 2015

The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “The God in the Bowl”

Bill Ward and I are working our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing story three, “The God in the Bowl.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are working our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing story three, “The God in the Bowl.” We hope you’ll join in!

Howard: While I understand it’s a different kind of story for Conan, and that it’s interesting to look at through the lens of understanding how Howard’s writing developed, I’m evaluating each of these tales with a fairly simple agenda foremost: Do I enjoy them as stories, and do they achieve what they’re designed to do?

In this case I think both answers are no. The reasons I don’t enjoy it are closely tied to my feelings about its failure as both a mystery and a horror story. The solution is pretty well telegraphed to the reader early on, leaving it not much of a mystery. And while there is exquisitely drawn horror present, I think the story lacks the requisite tension for a horror story (as opposed to a story WITH horror).

In this case I think both answers are no. The reasons I don’t enjoy it are closely tied to my feelings about its failure as both a mystery and a horror story. The solution is pretty well telegraphed to the reader early on, leaving it not much of a mystery. And while there is exquisitely drawn horror present, I think the story lacks the requisite tension for a horror story (as opposed to a story WITH horror).

There’s also confusion about who the protagonist is — the charismatic barbarian who stands around glowering and making cool threats, and clever Demetrio, whose cleverness is so belabored it becomes irritating. Demetrio’s the only one moving the plot forward (slowly) until the stunning action scenes when Conan takes over and the story becomes interesting once more, too late.

Midway through, Robert E. Howard writes of Demetrio that: “He found these scenes wearily monotonous.” And, unfortunately, that’s how I feel about most of “The God in the Bowl.” That’s not to say it’s completely without merit, for it has finely realized horror and some great action moments, but those moments don’t make it a success. They’re like hearing one really catchy song while having to sit through a long dreary musical at your kid’s high school.

Bill: The first, almost play-like half or two-thirds of the story has Conan standing on the sidelines while other characters talk. And then yet more characters show up. I think it’s the strong final moments of “The God in the Bowl,” though, that leave readers with a better overall impression of the story.

Bill: The first, almost play-like half or two-thirds of the story has Conan standing on the sidelines while other characters talk. And then yet more characters show up. I think it’s the strong final moments of “The God in the Bowl,” though, that leave readers with a better overall impression of the story.

Howard: You’re probably right. Let me highlight what I DO like. I think it starts with strong momentum before quickly coming to a dead stop. By itself, the conclusion, beginning with the entry of the aristocrat who denies hiring Conan for the robbery, is wonderful. With his appearance we get some really snappy dialogue, then the explosion of violence between Conan and the guards, and finally the confrontation with the monster, which goes to 11 on the atmospheric and eerie scale. And Conan himself seems fully gelled — this is the unstoppable powerhouse of destruction we know and love. I’ve studied Howard fragments, rough drafts that are worth reading solely because of an amazing action sequence delivered with pulse-pounding vigor and inventiveness. You can always count on Robert E. Howard for action scenes.

Bill: Yes, great stuff. The combat is quick and brutal and vivid — Conan even plucks a guard’s eye out for Crom’s sake — and most welcome after we’ve been standing around listening to all the talk. The Stygian Snake God, a gift from our old friend Thoth-Amon to a rival priest (I like how Conan and Thoth-Amon’s destinies seem intertwined at this point, as this encounter was just at the start of Conan’s career) is really excellent, reminding me of how a smart film director keeps his monster hidden and mysterious from the audience. Those are all my favorite moments as well, that and, as you say, a fully fleshed Conan responding to the questions and bullying of the civilized interrogators with characteristic ballsy aplomb.

Bill: Yes, great stuff. The combat is quick and brutal and vivid — Conan even plucks a guard’s eye out for Crom’s sake — and most welcome after we’ve been standing around listening to all the talk. The Stygian Snake God, a gift from our old friend Thoth-Amon to a rival priest (I like how Conan and Thoth-Amon’s destinies seem intertwined at this point, as this encounter was just at the start of Conan’s career) is really excellent, reminding me of how a smart film director keeps his monster hidden and mysterious from the audience. Those are all my favorite moments as well, that and, as you say, a fully fleshed Conan responding to the questions and bullying of the civilized interrogators with characteristic ballsy aplomb.

Also, another point, this story is Conan’s first appearance in what would become the all-time barbarian standard of dress in fantasy fiction — sandals and a loincloth!

Howard: Hah! Score one for the loincloth and sandals.

Howard: Hah! Score one for the loincloth and sandals.

It may seem I’m pretty harsh about a story written by one of my favorite writers starring one of my favorite characters, but it lacks elements of what I most love about Robert E. Howard’s writing. I think the flow is off. Usually you can count on Howard for pacing but this tale’s so drawn out that rather than feeling tension I start wondering how long it will take for the characters to get on with it.

Tension is further diluted because Conan doesn’t have much invested in the solution to the mystery — the guards are going to try to haul him away regardless. We can only watch as the man of action stands and listens to all the noise, noise, noise, noise. Demetrio thinks out loud and various bit players run in to report things that add information to what other bit players relayed. As you intimated, it’s a little like watching a dull stage play.

You could argue that I’m judging work from another time by pacing standards of our time, a mistake a lot of modern readers make when reading old adventure fiction. But this isn’t at all typical of Robert E. Howard’s style. One of the things I love about his work is that wonderful cinematic pacing, so unlike many of his predecessors and even contemporaries. If he was deliberately experimenting with a different storytelling style he inadvertently sidelined one of his greatest strengths when he did so.

Maybe if I’d read this for the first time when I was a teenager I wouldn’t have seen that conclusion coming. I can’t know — I can only react to what I first read in my 20s, and then it was clear to me from Howard’s own clues that the monster was some kind of huge-ass snake, the only (and truly creepy) surprise being its chilling face. If I focus on the horror aspect I imagine I’m supposed to feel nail-biting dread for understanding the danger that the characters do not and wondering how they can possibly survive… but that would have required me to care about more than one of them.

Maybe if I’d read this for the first time when I was a teenager I wouldn’t have seen that conclusion coming. I can’t know — I can only react to what I first read in my 20s, and then it was clear to me from Howard’s own clues that the monster was some kind of huge-ass snake, the only (and truly creepy) surprise being its chilling face. If I focus on the horror aspect I imagine I’m supposed to feel nail-biting dread for understanding the danger that the characters do not and wondering how they can possibly survive… but that would have required me to care about more than one of them.

Sorry, REH. I still think you’re awesome, I swear. I understand why Farnsworth Wright rejected this. And maybe you did too, because unlike you did with other unsold tales, you seem never to have tried revising it or sending it on to another market.

Bill: “The God in the Bowl” is similar to “The Phoenix on the Sword” in that other characters are the ones moving the plot forward, and Conan reacts to them. In both cases these are Conan vs. Civilization stories, whereas “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter” is Conan out in his own element. In none of these stories has Conan, I think, fully grown into his role as protagonist and driving force just yet — after all in “Frost-Giant” Conan is essentially bewitched. He certainly isn’t making choices. Looking at just “God” and “Phoenix,” it almost seems to me that REH needed to focus on the civilized players and their plots as a way of finding out who Conan was in contrast. After these first three tales, though, Conan is firmly in the driver’s seat for much of the rest of his stories.

Howard: In later stories Howard sets events in motion by showing us what’s under way before Conan wanders in and upsets the apple cart. I suppose that kind of happens here, but not in an especially interesting way. I wish he had rewritten it to trim it down, lengthwise, because the conclusion rocks, and there are several nice touches throughout — the cable that we readers are rightly suspicious of, various small character-revealing asides, and so on. Yes, there are good character moments, but I still didn’t find these other players compelling enough to watch them take center stage for so long.

Howard: In later stories Howard sets events in motion by showing us what’s under way before Conan wanders in and upsets the apple cart. I suppose that kind of happens here, but not in an especially interesting way. I wish he had rewritten it to trim it down, lengthwise, because the conclusion rocks, and there are several nice touches throughout — the cable that we readers are rightly suspicious of, various small character-revealing asides, and so on. Yes, there are good character moments, but I still didn’t find these other players compelling enough to watch them take center stage for so long.

Bill: I think we can both pretty easily imagine a better version of this story, no reason not to point out its flaws. I think the pacing issue becomes even more telling upon rereading, because there isn’t even the curiosity about the ending to supply interest. But from this point forward things change, Conan and REH hit their stride, and some immortal sword-and-sorcery stories start flying off the Underwood — next week’s “The Tower of the Elephant” shall be the first of many!

August 19, 2015

Howard’s Books on Kindle and Nook

I learned some more cool news yesterday — my first two Pathfinder novels, Plague of Shadows and Stalking the Beast, are now available on Kindle. I’m assuming that my new one will be as well, when it’s released in October.

I learned some more cool news yesterday — my first two Pathfinder novels, Plague of Shadows and Stalking the Beast, are now available on Kindle. I’m assuming that my new one will be as well, when it’s released in October.

Speaking of which, there are still twenty days left to enter the Goodreads contest for a chance to win a free copy of Beyond the Pool of Stars! Swashbuckling action! Hair-raising escapes! Lost jungle ruins! Lizardmen! A kickass female protagonist! What are you waiting for, eh?

August 14, 2015

The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter”

Bill Ward and I are working our way through the Del Rey Conan collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter.” We hope you’ll join in!

Howard: Those first two paragraphs are so well written I had to stop and re-read them. Here, again, is proof of Robert E. Howard’s incredible descriptive powers. Some of that talent seems to have been innate with him, but I can’t help thinking he’s even better than he could have been because he spent so much time working with poetry, where every word counts even more than in prose. Well, actually, every word in prose should count, but too often prose writers don’t write that way. Howard at his finest always remembers this.

Bill: Indeed. There is a lot of poetic language in this one, and I think you can see the poet in the writer in much of REH’s work, just as you can with that other Weird Tales luminary, Clark Ashton Smith. Two writers with different styles, perspectives, and even goals whose prose is clearly informed by the writing of poetry. In CAS’s case he was primarily a poet, though, and I think that comes through in his work just as much as it’s obvious that REH is a born storyteller.

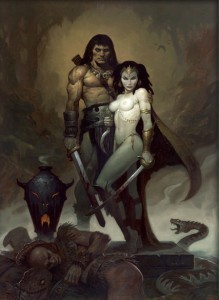

Art by Mark Schultz

Howard: Absolutely. A whole lot of this story is chock full of stunning description, although, clearly, the story’s not about lovely events. A battle, its aftermath, a woman with murder in her heart and a man who lusts for her. I’ve been a little leery of this one because it wanders into uncomfortable territory.

Bill: But so does a lot of myth, classical or otherwise. By coincidence I’ve been reading Ovid’s Metamorphoses lately, and it’s been suggested (in the “Hyborian Genesis” essay at the back of the Del Rey edition we are reading, for starters) that “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter” is possibly directly inspired by the Atalanta and Daphne & Apollo myths expounded by Ovid (the name of Ymir’s daughter, Atali, also seems to support this), and transmitted to REH through his reading of Bulfinch. Injecting that “divine lover’s pursuit” motif common with Classical cultures into a wintry Nordic context is one more interesting example of the Hyborian blender that allowed REH to be so inventive and to draw upon whatever source fired his imagination.

Art by Cary Nord

Howard: I’m glad you did the legwork on that one, Bill. I have to agree — this isn’t Conan under “normal operating conditions.” Although Conan finds the strange woman stunningly attractive from the first, he doesn’t seem determined to have her until she weaves a kind of spell on him. That it’s a spell and not natural inclination becomes more clear closer to the end of the story when we learn that she’s a northern goddess who lures dying men from battlefields with her beauty so that her brothers can slay them — although there are many clues along the way that she’s supernatural.

From other Conan stories this kind of ravenous, animal lust is no part of his character, but I can’t help thinking that first-time Conan readers would be turned off by the situation, especially because it’s not made entirely clear this isn’t his natural state. If you’re paying attention, I think it’s obvious, but if you’re not looking for subtlety, a mistake people often make when reading REH, you might not see it. Even still, it’s an uncomfortable situation. Farnsworth Wright might have thought so as well, because he didn’t accept it for Weird Tales. Like the next story on the docket, “The God in the Bowl,” it was rejected, and never printed as a Conan tale in Howard’s lifetime.

Art by Bruce Timm

Bill: And I scored extra nerd points this week by reading it in its reincarnated form, re-titled “Gods of the North,” in my facsimile reprint of The Fantasy Fan fanzine (March ’34). It stars “Amra of Akbitana” but is nearly identical to “The Frost-Giant’s Daughter,” though it includes a line that further details Amra’s travels in the south. This, I’m assuming, is the origin of Conan’s famous alias, and it’s great to see how the meta-events in the life of this character can turn around and influence his future fictional adventures.

And I agree, without making Conan’s magical compulsion more initially explicit, I could see “Frost-Giant” alienating readers, especially now. But Conan’s first impulse is to seek succor, to find Atali’s village, even though this woman “as beautiful as a frozen flame of hell” was standing completely naked before him.

Howard: An important point. She incites him to chase her so that she may have him killed by her brothers. He’s not in his right mind.

Art by Cary Nord

Bill: Right. She mocks him, dares him to follow her, draws him toward a trap, enchants him quite literally with her otherworldly beauty. Not a good call on her part, as her brother giants find out. Finally she has to call on her father Ymir, one of the North’s fierce gods who has been continually referenced in the story, to save herself. Conan had a supernatural foe in the previous story, but here he is defiant right in the teeth of divine malice, another facet of his character we see to lesser or greater degrees throughout his career.

And in terms of a career, this story is often given as the earliest in terms of internal chronology. Again, very interesting that the first two stories about Conan bracket his adventuring life, one at the very end, and one at the very start. It seems like a an organic way of discovering the character, both for us and REH. One more point against the pastiches — in forcing the stories into “career” order (and shoehorning in others, of course) it destroys the byplay between the stories — what do we see Conan mapping in “Phoenix?” The setting of the next story! Reading them in the order they were written lets us as readers share, right along with REH, in that oft-quoted phenomena of Conan simply telling us his adventures as they occur to him.

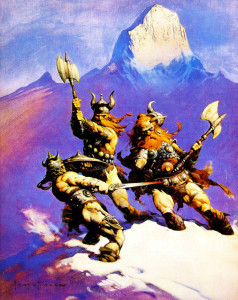

Art by Frank Frazetta

Howard: Oh, that’s a great catch Bill. I’d never noticed that wonderful juxtaposition of map maker to flashback of him in the place where he was making the map.

As to the story itself, it’s fairly simple, succeeding wholly because of Robert E. Howard’s polished prose. But, unlike next week’s tale, I find it well paced, completely achieving what it sets out to do.

Bill: In the hands of another writer it might have almost seemed a vignette, but it definitely works as a story as it stands, and the language is great. I think watching the evolution of the character and the stories themselves is possibly the most enjoyable aspect of these early stories for me, and the first three really seem to be building toward the classic trio that starts with “The Tower of the Elephant.” We’ll get to the last of these early three Conan tales next week, “The God in the Bowl.” Hope to see you here.

August 12, 2015

Win a Copy of My New Novel

Here’s a nifty thing. Courtesy of TOR and Paizo you can enter to win one of ten free copies of my new novel, Beyond the Pool of Stars, over at GoodReads!

And in case you haven’t seen it yet, here’s that glorious Tyler Jacobson wraparound art of the book’s cover again!

August 10, 2015

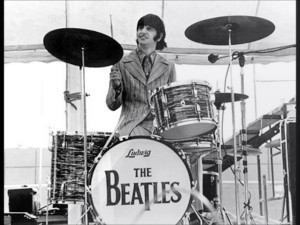

Ringo Needs More Love

On a long drive the other day, I was listening to “The Beatles,” aka “The White Album” and had some non-writerly non-bookish thoughts to share about it.

On a long drive the other day, I was listening to “The Beatles,” aka “The White Album” and had some non-writerly non-bookish thoughts to share about it.

Ringo continues to get a bad rap as a drummer. The idea is that he’s just a lovable, average lunkhead thrown in with three geniuses and that anyone could have filled those shoes, but that just doesn’t hold up to close scrutiny. If you listen to Beatles tracks and focus in on the percussion, you can hear how Ringo gives every single song a distinctive sound, so much so that if you were able to tune down the rest of the band you could identify a Beatles track just by what Ringo’s doing.

Sometimes I run across a quote wherein John Lennon was asked if Ringo were the greatest drummer in the world and he reportedly said: “he’s not even the greatest drummer in The Beatles.” It turns out that Lennon never actually said that — a comedian did years after Lennon’s death. All of The Beatles seemed to hold him in high regard and repeatedly emphasized to (often disbelieving) listeners that he was a vital part of the band. That, for instance, he almost always got the exact right sound the first time through and almost never flubbed a take, that his malapropisms inspired song titles, and that he was the missing ingredient that really helped the band gel.

Sometimes I run across a quote wherein John Lennon was asked if Ringo were the greatest drummer in the world and he reportedly said: “he’s not even the greatest drummer in The Beatles.” It turns out that Lennon never actually said that — a comedian did years after Lennon’s death. All of The Beatles seemed to hold him in high regard and repeatedly emphasized to (often disbelieving) listeners that he was a vital part of the band. That, for instance, he almost always got the exact right sound the first time through and almost never flubbed a take, that his malapropisms inspired song titles, and that he was the missing ingredient that really helped the band gel.

If you don’t believe any of this, try an ear test yourself. Listen to “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and pay particularly close attention to the percussion. That’s Paul McCartney as he’s just mastering the drums. He’s competent, but once you’re aware it’s him you can never NOT notice that there are some ragged parts. Contrast it with another track on the first side of the first disc of “the white album,” even the relatively minor “Glass Onion”. It should be immediately obvious what a difference a great versus competent drummer makes. Ringo, on “Glass Onion” is confident, assertive, driving. His presence makes the song stronger, opposed to the drums on “Back in the U.S.S.R.” which simply fade into the background.

If you don’t believe any of this, try an ear test yourself. Listen to “Back in the U.S.S.R.” and pay particularly close attention to the percussion. That’s Paul McCartney as he’s just mastering the drums. He’s competent, but once you’re aware it’s him you can never NOT notice that there are some ragged parts. Contrast it with another track on the first side of the first disc of “the white album,” even the relatively minor “Glass Onion”. It should be immediately obvious what a difference a great versus competent drummer makes. Ringo, on “Glass Onion” is confident, assertive, driving. His presence makes the song stronger, opposed to the drums on “Back in the U.S.S.R.” which simply fade into the background.

The more you pay attention, the more obvious Ringo’s contribution to the band’s sound becomes. In short, then, give Ringo your love. That’s all he needs, right?

August 7, 2015

The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “The Phoenix on the Sword”

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Conan collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The Phoenix on the Sword.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Conan collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The Phoenix on the Sword.” We hope you’ll join in!

Howard: Look at the story’s opening quote. That’s practically the gold standard of quotes from imaginary historical sources. That fabulous “Know, O Prince” and all that follows has been imitated but rarely, if ever, equalled. This, fellow fantasy fans, is the way it’s done. Admittedly, there are a few phrases in the middle of the paragraph that are less inspired. I’m looking at “Zingara with its chivalry, Koth that bordered on the pastoral lands of Shem.” Most of the rest of the quote paints lovely word pictures, but those phrases don’t remotely approach the poetic majesty of the rest — what does Zingara look like? What does Koth look like? But the rest is lovely, and the quality picks right back up with “dreaming west” and powers on to that fantastic finish, “Hither came Conan…”

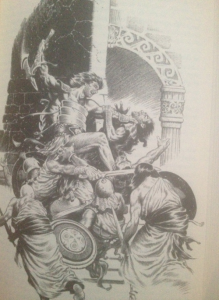

Mark Schultz artwork from The Coming of Conan.

Bill: Classic stuff, and apparently put there in the final draft at Wright’s insistence that Conan’s identity and the setting itself needed to be established earlier on in the story. Philistine that I am, I can never read it without hearing it in Mako’s voice, as it was also paraphrased at the start of the Milius Conan the Barbarian film.

Howard: I’d forgotten that was at Wright’s behest! And I, too, hear Mako’s voice.

Look at the opening line of the story: “Over shadowy spires and gleaming towers lay the ghostly darkness and silence that runs before dawn.” Damn. Why doesn’t anyone write like that any more? Howard sets the scene with sharp, sensory laden description. He’s a film director guiding the camera with a fantastic establishing shot.

Mark Schultz illustrating the assassination attempt.

Unfortunately, a lot of Part I feels a little old fashioned because it’s a fairly staged conversation to convey information we, the readers, need to know about what the villains are planning. This kind of information delivery is a pulp standard, and it was perfectly acceptable at the time of writing, but it hasn’t aged well. Even still, Part I is loaded with brilliant bits, one of my favorites being the discussion of Rinaldo and the habits of poets who seek perfection “behind the last corner, or beyond the next.”

Bill: Yes, “a poet always hates those in power.” This is one of the many things that survives from “By This Axe I Rule,” the unsold King Kull story REH rewrote as “The Phoenix on the Sword.” And those political or philosophical aspects of both are really interesting and nicely demonstrate REH’s attitude toward civilization and barbarism, which is the great theme that seems to permeate all his work. In both stories a barbarian King finds himself a kind of slave to the laws and customs of the people he would rule, enough of whom despise him purely for his foreignness. The Kull story explicitly makes slavery a theme, and Kull’s overthrowing of an ancient law is the culminating moment of the story. That aspect, wrapped around a simple love story, was replaced by Thoth-Amon (a slave at the start of the story) and the supernatural element in “Phoenix.”

Conan and Belit by Brom.

Howard: Part II opens with a stirring poetic fragment and gives us Conan for the first time. And what an impression he makes! I especially like “there was nothing deliberate or measured about his actions” and all that follows. Like part I, this section, too, has a lot of information conveyed a little stagily through dialogue, although it’s mixed with more realistic touches. The speakers are more complex than the villains of Part I. We get to know Conan’s inclinations, and admire his restraint. Here’s a wise, seasoned man striving to be a good ruler.

Bill: And notice how some more background is conveyed to us through Conan making maps! Not only does it remind me of REH’s own mapping for his Hyborian age, but it shows Conan both as an outsider and as a thoughtful man. His courtiers might think him an untutored barbarian, but he knows things and places that are but half-believed legends to them — knows those places, and adds them to the store of the civilized world’s knowledge, as well. It was a Cimmerian with wanderlust, not an Aquilonian explorer, who added Asgard and Vanaheim to the map of the known world. A nicely subtle way to get across Conan’s place within the society and station he finds himself, and a bit about the larger world as well.

Howard: I also like Prospero, whom we learn is one of the few familiar enough with his king to speak easily with him. He clearly has the best interest of his king at heart and strives to give him good counsel. I like that he’s not perfect. It may just be a clever trick of REH’s to show us a little more what Prospero looks like, but I love that he turns to consider himself in the mirror, suggesting that he’s just a little vain. I wish that he turned up in more Conan stories.

Howard: I also like Prospero, whom we learn is one of the few familiar enough with his king to speak easily with him. He clearly has the best interest of his king at heart and strives to give him good counsel. I like that he’s not perfect. It may just be a clever trick of REH’s to show us a little more what Prospero looks like, but I love that he turns to consider himself in the mirror, suggesting that he’s just a little vain. I wish that he turned up in more Conan stories.

Bill: As do I. Looking at the Kull story, Propero is clearly the analog to Brule, Kull’s great Pictish friend who appears in all or nearly all of his other adventures. I like that Prospero essentially inherits that role, that his character is richer and larger-seeming because of, I suspect, that feeling for those older characters that REH was building from. We can believe in Prospero and Conan’s friendship even though we never really see it.

Howard: Part III begins to ramp things up. Yes, it’s a bit awkward that we get Thoth-Amon’s backstory in dialogue and that Dion just happens to have the ring, but I still kind of love it, particularly the way REH handles the noble who doesn’t really pay attention to anything the slave’s saying and loses his life as a result, or the way we’re shown Thoth-Amon’s duplicity and ruthlessness. This may not be top drawer Conan, but it’s surely entertaining. And this section concludes what may be the finest atmospheric writing in the entire story. From the point when Thoth-Amon kills Dion to the end of the section is pure prose poetry, Howard at his very best.

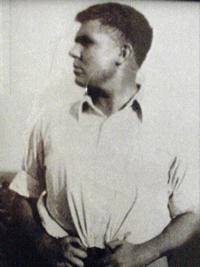

Robert E. Howard

Bill: I agree — the first time I read the story I may have felt more strongly that some of these early sections were flawed or awkwardly paced, but it’s also rather efficient storytelling, and certainly well within the conventions of its day. The summoning scene, where Thoth-Amon doesn’t turn around despite the cold wind at his back, was creepy excellence.

Howard: With all the motivations out of the way, Robert E. Howard gets to exciting action and combat, although there’s a brief detour to the halls of an ancient sage in the land of dreams before we get finally to the explosive conclusion, drawn with the stunning clarity Howard is rightly famed for. It’s a thrill ride, but in the end it’s a little disjointed, and once you know the history of the tale as a revision from a Kull story the reasons are obvious. I don’t think I’m the only one who finds “By This Axe I Rule” a stronger piece, but it was rejected by Weird Tales Editor Farnsworth Wright because it lacked supernatural elements. REH, professional in need of a paycheck that he was, promptly re-envisioned it and stuffed the tale full of supernatural incidents. Once you’ve read THAT yarn, “The Phoenix on the Sword” seems more slap dash, although it did give Wright what he wanted.

Bill: Both stories have that somewhat unusual structure in which we arrive at our protagonist only after hearing about him from minor characters, and I’ve read that they were inspired by Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, which would help explain the focus on the conspirators. But I think “Phoenix” is a superior story to “Axe” because it seems to better integrate those two plot lines. The Kull story is indeed a good one, and in both pieces REH elevated the simple conflict with a thematically unified rumination on kingship, freedom, slavery, and civilization. But I think the Thoth-Amon element functions both to give us some cool weird horror, and to further hit at those themes. With Thoth-Amon, the conspirators themselves are undone by the same base human nature that led to them wanting to assassinate Conan in the first place, and their attack on the King is spoiled not by a loyalist, but by yet another betrayer. Like Thoth-Amon’s ring, they are eating their own tail, and Conan stands oddly outside and apart from all that in a way that Kull doesn’t. The monster Conan slays wasn’t even meant for him, his spiritual aid is clearly granted more to the King of Aquilonia than any Conan the Cimmerian. Even as a King, he’s more of an outsider to this world than he ever was as a thief or mercenary.

Bill: Both stories have that somewhat unusual structure in which we arrive at our protagonist only after hearing about him from minor characters, and I’ve read that they were inspired by Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, which would help explain the focus on the conspirators. But I think “Phoenix” is a superior story to “Axe” because it seems to better integrate those two plot lines. The Kull story is indeed a good one, and in both pieces REH elevated the simple conflict with a thematically unified rumination on kingship, freedom, slavery, and civilization. But I think the Thoth-Amon element functions both to give us some cool weird horror, and to further hit at those themes. With Thoth-Amon, the conspirators themselves are undone by the same base human nature that led to them wanting to assassinate Conan in the first place, and their attack on the King is spoiled not by a loyalist, but by yet another betrayer. Like Thoth-Amon’s ring, they are eating their own tail, and Conan stands oddly outside and apart from all that in a way that Kull doesn’t. The monster Conan slays wasn’t even meant for him, his spiritual aid is clearly granted more to the King of Aquilonia than any Conan the Cimmerian. Even as a King, he’s more of an outsider to this world than he ever was as a thief or mercenary.

Howard: Huh — alright, maybe you’ve convinced me to reconsider which of the tales I find superior. I may have to re-read “By this Axe I Rule” tonight and compare them freshly. I’m particularly impressed with your analysis re: the outsider, and how Conan remains one throughout.

Whatever the rest of you thought of the story’s merits and flaws, rest assured that there are stronger Conan stories yet to come, although I’m not sure next week’s is among them. I haven’t revisited it even half as often as the one that lies three weeks out. In any case, join us next week for “The Frost Giant’s Daughter” and feel free to comment below!

August 5, 2015

My Favorite T-Shirt

GenCon attendees Wednesday night might have seen me sporting my favorite t-shirt. It’s also my first born’s favorite t-shirt, and seeing as how he’s somehow gotten as tall as me, I turn it over to him sometimes for special occasions.

GenCon attendees Wednesday night might have seen me sporting my favorite t-shirt. It’s also my first born’s favorite t-shirt, and seeing as how he’s somehow gotten as tall as me, I turn it over to him sometimes for special occasions.

Anyway, said first-born spotted a pretty cool pic of someone holding said t-shirt the other day, and I thought I’d share it with you.

I’m not quite done with my GenCon wrap-up article I thought I’d be posting today. Fiction writing is going great, although I’m still suffering from some sleep deprivation due to the con. I just didn’t sleep well at the convention, despite not being up TOO late. At least, though, I didn’t come home sick like a lot of my friends and colleagues. A lot of times conventions end up as breeding grounds for illnesses and I usually work to stay hydrated. I guess that did the trick.

Howard Andrew Jones's Blog

- Howard Andrew Jones's profile

- 368 followers