Howard Andrew Jones's Blog, page 37

December 14, 2015

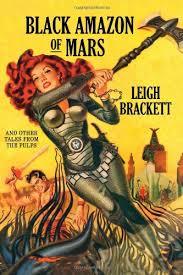

Monday Morning Brackett

It’s been a madhouse here with me working pretty much night and day towards a book deadline, so my weekly posts have been greatly reduced. I should have things back to at least three updates (hopefully interesting ones) a week, possibly THIS week.

It’s been a madhouse here with me working pretty much night and day towards a book deadline, so my weekly posts have been greatly reduced. I should have things back to at least three updates (hopefully interesting ones) a week, possibly THIS week.

Right now I need to go make some final adjustments to some action sequences, but I wanted to leave you with some links to other Leigh Brackett articles that popped up over the last few days.

Keith Taylor at the Two Gun Raconteur

On a disappointing note, there’s apparently been some controversy about just how useful Brackett was to The Empire Strikes Back, and related matters. There’s a nice rebuttal here, which should catch you up if it’s new to you. I think I’m most saddened that SO many people are only going to be hearing about her in relation to Star Wars and might be less inclined to seek out her work owing to some of the articles circulating. Brackett is FAR more important to science fiction and fantasy than Star Wars… except that Star Wars seems to have penetrated the public consciousness to a far greater extent, so in the long run perhaps she isn’t. And that also saddens me. She was so far ahead of her time that I wonder if Star Wars or Firefly would even have existed without her blazing a trail.

On a disappointing note, there’s apparently been some controversy about just how useful Brackett was to The Empire Strikes Back, and related matters. There’s a nice rebuttal here, which should catch you up if it’s new to you. I think I’m most saddened that SO many people are only going to be hearing about her in relation to Star Wars and might be less inclined to seek out her work owing to some of the articles circulating. Brackett is FAR more important to science fiction and fantasy than Star Wars… except that Star Wars seems to have penetrated the public consciousness to a far greater extent, so in the long run perhaps she isn’t. And that also saddens me. She was so far ahead of her time that I wonder if Star Wars or Firefly would even have existed without her blazing a trail.

Commenters on Sarah Hoyt’s site, linked above, suggest that the reason Brackett’s forgotten is that she’s a conservative and that there’s some kind of conspiracy from the substantially liberal writing industry.

I happen to be fairly liberal in my social and religious outlook and have known for ages that two of my three biggest writing heroes were conservatives. It hasn’t ever stopped me from digging them, but perhaps that’s a comment upon me rather than others. In any case, I don’t think Brackett’s political opinions are widely known anymore, and am more inclined to believe her relative obscurity can be traced to two things.

1. Lack of a sense of history among fantasy and science fiction readers, who seem only to read what’s currently in print, and 2. The simple fact that Brackett only ever created ONE series character. And, let’s face it, Stark only turns up in three short stories before appearing in three novels at the end of Brackett’s career (and, long after her death, Stark appears in a fourth weak tale she wrote with Edmund Hamilton). The short stories set on a Mars and Venus that don’t exist, and modern readers don’t seem to be able to deal with that. Maybe if the novels had been fantastic with a capital F it would have made a difference, but the third one always read to me like a contractual obligation, which was a real disappointment.

1. Lack of a sense of history among fantasy and science fiction readers, who seem only to read what’s currently in print, and 2. The simple fact that Brackett only ever created ONE series character. And, let’s face it, Stark only turns up in three short stories before appearing in three novels at the end of Brackett’s career (and, long after her death, Stark appears in a fourth weak tale she wrote with Edmund Hamilton). The short stories set on a Mars and Venus that don’t exist, and modern readers don’t seem to be able to deal with that. Maybe if the novels had been fantastic with a capital F it would have made a difference, but the third one always read to me like a contractual obligation, which was a real disappointment.

It’s my guess that if she had created more series characters, or had written more adventures featuring Stark, she would be more widely read. People just seem to prefer revisiting the same characters rather than constantly being introduced to new ones. For many readers it’s not the author who matters as much as the characters. To paraphrase Spock (well, Theodore Sturgeon), it is not logical, but it is often true.

Incidentally, speaking of Stark, Haffner Press recently announced that there’s going to be another Brackett hardback from their stable, so if you’re wanting a complete collection of her tales — including the outline for the fourth, never written Stark novel — you should send them money. I know I will.

December 11, 2015

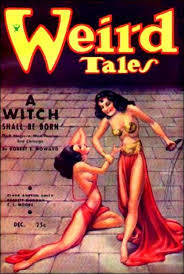

Conan Re-Read: “A Witch Shall Be Born”

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing “A Witch Shall be Born.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing “A Witch Shall be Born.” We hope you’ll join in!

Howard: I had hoped to like this one more. I’ve only read it once before, and I hadn’t remembered it being quite so frustrating. Coming as it does on the heels of a sword-and-sorcery masterpiece it’s even more of a let down, and it seems hard to believe that the man who just gave us such a spellbinding story should trip this way.

Bill: It’s like the steep initial drop on a roller-coaster, minus the exhilaration.

Howard: Hah! In the first half of the story there’s one real standout scene, and if you’ve just read the tale you probably know the one I’m talking about — where Conan himself is crucified. More on that in a moment. First, though we have an opening where an evil twin materializes and then explains the whole of her backstory and her plan to the good Queen Taramis. It’s reminiscent of the second opening sequence in “Black Colossus” save that it goes on for far too long and ends with the intimation that the queen has probably been raped.

Howard: Hah! In the first half of the story there’s one real standout scene, and if you’ve just read the tale you probably know the one I’m talking about — where Conan himself is crucified. More on that in a moment. First, though we have an opening where an evil twin materializes and then explains the whole of her backstory and her plan to the good Queen Taramis. It’s reminiscent of the second opening sequence in “Black Colossus” save that it goes on for far too long and ends with the intimation that the queen has probably been raped.

From that ugly start we shift to a long monologue, in the style of a play, where a young soldier named Valerius relays all that he has seen in the recent battle, including, at last, what’s happened to Conan. This, too, wanders on. This sort of tale of the battle from someone else worked so very well in The Hour of the Dragon, but here it’s just details of the inevitable from the viewpoint of someone we haven’t learned to care about.

Bill: Exactly what I was thinking, and this sums up the major problem with the story. The old “show, don’t tell” adage may be over-stated to the point of absurdity in writing circles these days, but it certainly applies here. Valerius’s account, the scholar’s letter, more exposition from an undercover Valerius, Salome being told the outcome of the battle outside the city via her spy’s report … REH has so much information relayed through secondhand means that there isn’t much actual narrative story left to enjoy. What worked brilliantly on multiple occasions in The Hour of the Dragon is used here in almost the worst possible way. The only scenes that really work are the two Conan scenes and, to a much lesser extent, the climax of Taramis’ rescue and the re-taking of the city. The pace is off, there’s no sense of adventure or momentum, and there is very little from the cast of minor characters to hold the reader’s interest. How Farnsworth Wright could tell REH that this was his best Conan story to date boggles my mind.

Bill: Exactly what I was thinking, and this sums up the major problem with the story. The old “show, don’t tell” adage may be over-stated to the point of absurdity in writing circles these days, but it certainly applies here. Valerius’s account, the scholar’s letter, more exposition from an undercover Valerius, Salome being told the outcome of the battle outside the city via her spy’s report … REH has so much information relayed through secondhand means that there isn’t much actual narrative story left to enjoy. What worked brilliantly on multiple occasions in The Hour of the Dragon is used here in almost the worst possible way. The only scenes that really work are the two Conan scenes and, to a much lesser extent, the climax of Taramis’ rescue and the re-taking of the city. The pace is off, there’s no sense of adventure or momentum, and there is very little from the cast of minor characters to hold the reader’s interest. How Farnsworth Wright could tell REH that this was his best Conan story to date boggles my mind.

Howard: Exactly! All I can think of is that Wright really enjoyed “spicy” stories, because this one certainly has what the pulps called spice, meaning a whole lot of naked quivering woman flesh. We haven’t read so much about naked women in a Conan story since “The Vale of Lost Women.” I happen to be a big fan of lovely women, but there’s far too much textual description given over to their movements in this tale.

Howard: Exactly! All I can think of is that Wright really enjoyed “spicy” stories, because this one certainly has what the pulps called spice, meaning a whole lot of naked quivering woman flesh. We haven’t read so much about naked women in a Conan story since “The Vale of Lost Women.” I happen to be a big fan of lovely women, but there’s far too much textual description given over to their movements in this tale.

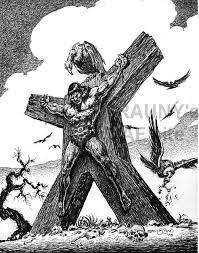

When we do finally get to Conan, it’s a standout moment of endurance, not to mention mythic parallel. So much has been written about this scene that I’m not sure I can do it justice. Suffice to say that it elevates the entire story; I wish the rest of “A Witch” deserves it. When I assemble my “best of” list at the end of our re-read this tale certainly won’t be in it, but this scene might be.

Bill: Fantastic, powerful writing in the crucifixion scene, for sure, it almost made me squirm. And it goes beyond the mere outlining of pain, we also see the indomitable spirit of Conan win through — a man that fights to the last breath, with his teeth if needed. Here is what a barbarian is all about, with his “life nailed to his spine” as he later tells Constantius, after turning the tables on him. Olgerd Vladislav’s torments as he rescues Conan only heighten the whole thing — Conan doesn’t just survive being crucified, he’s cut down like a tree, pulls out the nails himself once he gets his hands free, and then mounts and rides through ten miles of desert without a drink of water. Holy Crom!

Howard: My hopes were raised by the quality of that scene, and I wondered if perhaps the rest of the story would catch fire, but then the next segment is a long letter from someone we haven’t met detailing all the events taking place in the city over the span of the last seven months. Valerius, we learn, is missing and presumed dead, and Conan is now a rebel leader. As with the interlude before the crucifixion scene, all interesting details are happening off-stage. I almost get the sense that REH was bored with all the intervening moments.

Howard: My hopes were raised by the quality of that scene, and I wondered if perhaps the rest of the story would catch fire, but then the next segment is a long letter from someone we haven’t met detailing all the events taking place in the city over the span of the last seven months. Valerius, we learn, is missing and presumed dead, and Conan is now a rebel leader. As with the interlude before the crucifixion scene, all interesting details are happening off-stage. I almost get the sense that REH was bored with all the intervening moments.

Bill: Honestly, I think this should have been a draft. There are plenty of good ideas in this story, and I suspect it probably even works pretty well adapted as a comic.

Howard: I’ve got it in a Savage Sword of Conan collection. I’ll see how it plays out, because I think you’re right. It does read more like an outline.

Bill: It also doesn’t seem to have any real emotional anchor. REH is getting all those ideas out fast, but he’s not giving us the through-line of motivation beyond the most tenuous. We never spend enough time with Conan to really feel the simmering rage that led him to plot the take over of the Zuagir raiders. The idea of Conan being a minor character in one of his own stories isn’t necessarily an inherently bad one, but “A Witch Shall Be Born” never succeeds in making the non-Conan sections compelling. And the Conan scenes are so good, the rest only suffers even further in comparison.

Bill: It also doesn’t seem to have any real emotional anchor. REH is getting all those ideas out fast, but he’s not giving us the through-line of motivation beyond the most tenuous. We never spend enough time with Conan to really feel the simmering rage that led him to plot the take over of the Zuagir raiders. The idea of Conan being a minor character in one of his own stories isn’t necessarily an inherently bad one, but “A Witch Shall Be Born” never succeeds in making the non-Conan sections compelling. And the Conan scenes are so good, the rest only suffers even further in comparison.

Patrice Louinet suggests that this story was written in a few days, and I can understand how REH, in going from a long, layered, multi-draft project like The Hour of the Dragon, was eager to get another short story in the can for his number one market. None of his ideas here are bad, it’s just in the execution where it all falls apart. The fact that Wright lapped it up suggests that REH was doing exactly the smart thing with this approach — how could he even imagine a future where he’d be the object of adoration and scholarly analysis, the source of a multi-million dollar IP, and the inspiration for the Howard Andrew Jones and Bill Ward Great Conan Re-Read? Sadly, posterity has to point out the misstep, and there is no way to wax poetic about REH’s genius without applying the same critical eye to his mistakes.

Howard: I know. Sometimes when I write badly about his work I’m afraid someone’s going to revoke my REH fan club card. Look, he’s one of my very favorite writers. That doesn’t mean I love everything he wrote any more than I love every Beatles song even though I’m a huge fan of the Fab Four. “A Witch Shall be Born” suffers from numerous problems, perhaps the most obvious one being Robert E. Howard’s palpable disinterest in the story apart from the scenes with Conan in them. Every other is just set up so that we know there’s a hideous monster, so that we know what the villains are planning and why, etc. The climactic conclusion had a little more oomph, but even its last moments were a bit of a let down. I think REH must have been tired of monster battles, because he just has the weird thing go down under a flight of arrows.

Howard: I know. Sometimes when I write badly about his work I’m afraid someone’s going to revoke my REH fan club card. Look, he’s one of my very favorite writers. That doesn’t mean I love everything he wrote any more than I love every Beatles song even though I’m a huge fan of the Fab Four. “A Witch Shall be Born” suffers from numerous problems, perhaps the most obvious one being Robert E. Howard’s palpable disinterest in the story apart from the scenes with Conan in them. Every other is just set up so that we know there’s a hideous monster, so that we know what the villains are planning and why, etc. The climactic conclusion had a little more oomph, but even its last moments were a bit of a let down. I think REH must have been tired of monster battles, because he just has the weird thing go down under a flight of arrows.

Bill: Yes, Thaug was no Thog, that’s for sure; if it wasn’t for the accompanying illustration in the Del Rey edition I’m not sure the scene would have had any impact on me at all.

Howard: I probably won’t re-reading this one, apart from the aforementioned scenes.

Howard: I probably won’t re-reading this one, apart from the aforementioned scenes.

Bill: I suspect I’ll dust it off again one day, maybe with a little skimming. Sometimes it’s both reassuring and edifying to see evidence that a great artist is not in fact superhuman. And, honestly, the proof that REH was only human just serves to underline how utterly impressive the vast body of his work really is. But I sure wouldn’t hand it to an REH newcomer.

Howard: Absolutely. And I’ll have an example of another Conan tale not to do that with in the next collection, because it delayed my exploration of Conan for another two or three years longer. And you’re right that it IS refreshing to see that even genius falters. Not that I take any pleasure from that. Like most Conan fans, I simply wish that there were more of these stories from Howard’s underwood, or if not more, then that these mis-steps and leftovers were at the same level as the finest. Ah well.

Next week Bill and I will be looking at “The Servants of Bit-Yakin,” also known as “Jewels of Gwahlur.” I remember it as being another minor Conan tale, but I also recall enjoying it a great deal more than I liked reading this one. I guess I’ll find out soon. Thus concludes our re-read of The Bloody Crown of Conan — on to The Conquering Sword of Conan! Hope to see you here next week.

December 7, 2015

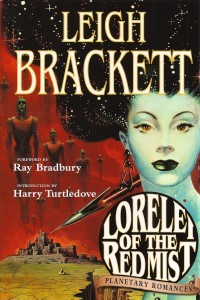

Leigh Brackett: “The Moon that Vanished”

The great Leigh Brackett was born 100 years ago today. She put Adventure into planetary adventure the way few others did before or since, painting her settings with astonishing color and details that never detracted from the story. I’ve written about this in detail here, if you’re after a few samples of her prose and a light discussion of her technique.

The great Leigh Brackett was born 100 years ago today. She put Adventure into planetary adventure the way few others did before or since, painting her settings with astonishing color and details that never detracted from the story. I’ve written about this in detail here, if you’re after a few samples of her prose and a light discussion of her technique.

Today, though, hopefully you can join Bill Ward and me in celebrating Leigh Brackett by discussing one of her great stories, “The Moon that Vanished.” If you missed the announcement last week, you can still join in by grabbing a . You won’t regret it.

Howard: As usual, Brackett begins with the story already underway. And, as is often the case, I find it can only add to the enjoyment of a Brackett tale if you picture Humphrey Bogart as the main character, because the story is infused with the melancholy air of a great hardboiled story. Her characters are world-weary and damaged.

Howard: As usual, Brackett begins with the story already underway. And, as is often the case, I find it can only add to the enjoyment of a Brackett tale if you picture Humphrey Bogart as the main character, because the story is infused with the melancholy air of a great hardboiled story. Her characters are world-weary and damaged.

There is tension from the very start. Tension, and mystery. The questions about why this pathetic Heath fellow is here, and what others want with him is quickly followed by concerns about his own status as a protected pariah and what exactly that means. We learn, before long, when Heath demonstrates his power, but we don’t learn the how of his heartsickness — the means of Ethne’s death — only the implied why. A lesser writer would have slowed us down with the details at the start. Not Brackett. The missing backstory remains a hook pulling us forward.

Bill: And she continues to tease out the mystery right up until the point where Heath and company actually confront their goal. As this was my first time reading this story, I’ll attest she had my interest from the start. The nature of the Moonfire, Heath’s loss, and his strange powers and status, are doled out in small, and sometimes subtle, pieces.

Howard: I love how she establishes atmosphere and setting at the same time she creates character, and sometimes a single word adds enough additional information to give you just a little more. For instance, “…where the captains and mates sat, playing their endless and complicated dice games…” We get a picture there not just of what they’re doing, but the manner in which they’re doing it, all with a few short words. But this is nothing compared to the full flower of her descriptive prose. When she wants to bring the poetry, she does it at the Chandler level. Here’s dawn over The Sea of Morning Opals:

Howard: I love how she establishes atmosphere and setting at the same time she creates character, and sometimes a single word adds enough additional information to give you just a little more. For instance, “…where the captains and mates sat, playing their endless and complicated dice games…” We get a picture there not just of what they’re doing, but the manner in which they’re doing it, all with a few short words. But this is nothing compared to the full flower of her descriptive prose. When she wants to bring the poetry, she does it at the Chandler level. Here’s dawn over The Sea of Morning Opals:

It came slowly, sifting down like a rain of jewels through the miles of pearl-grey cloud. Cool and slow at first, then warming and spreading, turning the misty air to drops of rosy fire, opaline, glowing, low to the water, so that the little ship seemed to be drifting through the heart of a fire-opal as vast as the universe.

The sea turned color, from black to indigo streaked with milky bands. Flights of the small bright dragons rose flashing from the weed-beds that lay scattered on the surface in careless patterns of purple and ochre and cinnabar and the weed itself sired with dim sentient life, lifting its tendrils to the light.

Bill: I was struck by how colorful and vivid her descriptions were, but she never oversells it or gets purple. Her prose is concise, but you’d never call it barebones. Even when the pace increases to a fast clip, she’s in control.

Bill: I was struck by how colorful and vivid her descriptions were, but she never oversells it or gets purple. Her prose is concise, but you’d never call it barebones. Even when the pace increases to a fast clip, she’s in control.

Howard: Absolutely. And how about how she describes Alor? Some writers are enormously adept at creating a crystal clear image of a person so that you’re probably imagining exactly what they envisioned. This was one of Ian Fleming’s greatest gifts. Brackett’s capable of that, but she also can do this, presenting a character through feeling. And damn, but this is great stuff. Here’s a sober Heath really looking at Alor for the first time:

His eyes were on the woman. She was tall but not too tall, young but not too young. Her body was everything a woman’s body ought to be, of its type, which was wide-shouldered and leggy, and she had a fine free way of moving it. She wore a short tunic of undyed spider silk, which exactly matched the soft curling hair that fell down her back — a bright, true silver with little peacock glints of color in it.

Her face was one that no man would forget in a hurry. It was a face shaped warmly and generously for all the womanly things — passion and laughter and tenderness. But something had happened to it. Something had given it a bitter sulky look. There was resentment in it and deep anger and hardness — and yet, with all that, it was somehow a pathetically eager face with lost and frightened eyes.

Heath remembered a day when he would have liked to solve the riddle of that contradictory face. A day, long ago, before Ethne came.

When I read the best of Brackett I feel like she’s taking me to school. That’s just some grand writing. Of course, she doesn’t do that with every character — that would get boring, fast. But here, with Heath’s future love interest, we see her described in a way that lets us finish the details. And note how in the end it still has mystery pulling us forward.

When I read the best of Brackett I feel like she’s taking me to school. That’s just some grand writing. Of course, she doesn’t do that with every character — that would get boring, fast. But here, with Heath’s future love interest, we see her described in a way that lets us finish the details. And note how in the end it still has mystery pulling us forward.

Bill: And she’s also telling us something about Heath as she describes Alor from his perspective, only reinforcing the feeling that there are no words wasted in this story. Brackett does the same in describing the specific brand of darkness on Venus in a way that mirrors the lost and dejected Heath himself, at the start of the story: “the planet is hungry for light and will not let it go.” The same is true for the man that can’t let go of his lost love as he rots away his life in a drug den.

Howard: Yes — all wonderful, subtle parallels. From the opening mystery of why Heath is interesting and what anyone would want with him we quickly move on to the mystery of what the Moonfire truly is, and the external tension of pursuit, not to mention the internal stresses of Heath and Alor falling in love even as the angry uplands barbarian looks on. There are environmental hazards, from the wonderfully named Dragon’s Throat to the monsters that lurk in the deep muck, and the clinging weeds.

Bill: I really like the weed-knife on the front of the boat; details like that are what sell an exotic setting. Green-skinned dancing girls, little dragons, names like The Palace of All Possible Delights and The Ocean-That-Is-Not-Water, all work to suggest a world without the need for reams and reams of elaboration. Of course, the length of the piece is a big factor as to why this approach works so well, but I do wish some modern fantasy writers would dial back the “details-for-details’-sake” aesthetic and take a page from writers like Brackett who cut their teeth in magazine fiction. Not everyone needs to be Tolkien.

Bill: I really like the weed-knife on the front of the boat; details like that are what sell an exotic setting. Green-skinned dancing girls, little dragons, names like The Palace of All Possible Delights and The Ocean-That-Is-Not-Water, all work to suggest a world without the need for reams and reams of elaboration. Of course, the length of the piece is a big factor as to why this approach works so well, but I do wish some modern fantasy writers would dial back the “details-for-details’-sake” aesthetic and take a page from writers like Brackett who cut their teeth in magazine fiction. Not everyone needs to be Tolkien.

Howard: She does get the setting across quickly, doesn’t she? The setting, and the atmosphere. Overlaid across it all is the fear of the Moonfire itself. Will they get there? What will happen when they do? It’s all just about perfectly paced. Nothing comes easily — everything is earned. For instance, even though Heath makes a compelling argument to Broca once he’s trying to leave, the barbarian may seem convinced, but he’s still willing to kill. Heath has to fight his way out, threatening the only thing that Broca holds dear.

Bill: All of which is set up earlier in the personalities and conflict between the characters. Having the fantastical, created worlds of the Moonfire reflect the psychology of the characters, and hinging the story on that, is why the ending resonates so well. Broca is the only one looking for power, his created world an extreme version of barbarian chiefly splendor. Heath’s desire has always been love — he was willing to die alongside the mere image of his lost Ethene, his drugged stupor in the beginning of the story the flipside of whatever virtual world he could create for himself in the Moonfire. Alor is seeking the same thing, after a life of being used and possessed, but never loved. It’s only that desire that lets them reject the temptation of godhood, the realization that their own act of omnipotent creation isn’t a substitute for real love and real life.

Bill: All of which is set up earlier in the personalities and conflict between the characters. Having the fantastical, created worlds of the Moonfire reflect the psychology of the characters, and hinging the story on that, is why the ending resonates so well. Broca is the only one looking for power, his created world an extreme version of barbarian chiefly splendor. Heath’s desire has always been love — he was willing to die alongside the mere image of his lost Ethene, his drugged stupor in the beginning of the story the flipside of whatever virtual world he could create for himself in the Moonfire. Alor is seeking the same thing, after a life of being used and possessed, but never loved. It’s only that desire that lets them reject the temptation of godhood, the realization that their own act of omnipotent creation isn’t a substitute for real love and real life.

Howard: It would have been a mis-step to have another physical confrontation as the last challenge, once they finally escape the Moonfire; instead we get a fantastic social conflict, one of the most memorable scenes in the story, when Vakor and the Children of the Moon can see that the Moonfire has transformed Heath and Alor.

More deeply, it’s love that transformed them, burning off the dross and making them pure. It was what allowed them to survive their terrible ordeal within the Moonfire, and at a deep level this story is all about love and its ability to bring out the best in us.

Bill: And that the notion of omnipotence is perhaps an illusion — all the power in the Moonfire could not make Alor love Broca, after all; and nothing but love could make Heath reject the seductive power of absolute creation. In the end, the world Heath and Alor share in happiness is a reflection of the artificial one Heath nearly loses himself to in the Moonfire, with the profound difference that it is not a mere shadow of his desires, but a shared reality not dependent on his will.

Bill: And that the notion of omnipotence is perhaps an illusion — all the power in the Moonfire could not make Alor love Broca, after all; and nothing but love could make Heath reject the seductive power of absolute creation. In the end, the world Heath and Alor share in happiness is a reflection of the artificial one Heath nearly loses himself to in the Moonfire, with the profound difference that it is not a mere shadow of his desires, but a shared reality not dependent on his will.

Howard: If there are any flaws here, they’re only those we impose upon a story looking back on it decades after its creation. There’s some idle hand waving about a scientific explanation of what the Moonfire is and a discussion of “radiation.” Why not? It’s really just a stand-in for an explanation that would have been given as sorcery in a modern fantasy tale. (And really, this is nothing BUT fantasy, held tenuously to the science fiction field because he’s a man from Earth and this is “Venus.”) I always find it a little jarring that Alor simply tells Heath that she loves him, and then remind myself that these are blunt people in stressful situations, and then it feels not the least bit forced.

In a society of the far future we can suppose that flyers and space ships could have easily reached the location of the Moonfire and explored and explained it, but we’re not really given a sense of how sophisticated our world travelers and their instruments are, or what taboos might be in place to keep such expeditions away.

In a society of the far future we can suppose that flyers and space ships could have easily reached the location of the Moonfire and explored and explained it, but we’re not really given a sense of how sophisticated our world travelers and their instruments are, or what taboos might be in place to keep such expeditions away.

Bill: I suspect Brackett could just as easily supply an explanation that it is the radiation that destroys a ship’s ability to explore the Moonfire. But really, as you say, this is fantasy adventure from the days before genre stringency and NASA data cut the legs out from under planetary romance. We hear very little about science fictional ideas here. It’s barbarians and gods and unknown powers that the story concerns itself with.

Howard: I had a great time re-reading this. I’m starting to realize that my ability to read quickly has sometimes impaired my ability to truly savor. When I slow down and soak up the words I think I enjoy the text and learn more from it. I had remembered that this was a good story, but I’d forgotten most of the details. Now that I took my time with this third visit, I think many of them are stuck for good, and I look forward to re-reading more. Bill and I will be visiting Brackett’s work over the course of the next year, shortly after we finish our Conan re-read.

Here’s a fine retrospective of her life and work. I’ll be linking to additional Brackett celebrations through the course of the week.

December 4, 2015

Conan Re-Read: The Hour of the Dragon, Part 2

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing the second half of “The Hour of the Dragon.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing the second half of “The Hour of the Dragon.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill: It is only at the midpoint of The Hour of the Dragon that Conan learns the full significance of the Heart of Ahriman, the terrible jewel with the intrinsic power to recall the dead to life or enhance sorcery beyond the bounds of mortal power. He learns this from the priests of Asura, a cult that he has shielded from persecution during his reign, and the same priests not only shelter him and the recently rescued princess Albiona, but they also facilitate his journey southward. From this point until its conclusion, the novel is a race for the jewel as Conan travels not only through the Hyborian Age landscape, but through his own past lives as mercenary, pirate, and thief.

Howard: That’s a really good point, Bill. Conan DOES face what he has been, drawing on his experiences and showing us a little how he’s changed. We can wonder whether this was a deliberate ploy of REH to show how Conan functioned in these different environments, slightly changed, or if it was just a simple way to create some action in fields Robert E. Howard was used to working Conan in… but it was probably both, and it works brilliantly.

Bill: The headlong pace of this section of the novel is nothing short of dazzling. Conan pursues, and is himself pursued. He comes close to getting the Heart of Ahriman twice, only to have it snatched away by other hands. He moves from the frontiers of Aquilonia to the Argossean shore, and even to the dark land of Stygia itself — the first time this region, so often mentioned by REH, is featured in a story. From one adventure to the next, from perils supernatural and human, and from one role to another, the pace of the plot is matched only by the pace of the author’s invention.

Howard: And it’s not a frying pan to fire kind of Burroughsian plotting, which, while fun, can grate a little. There’s more to it than that, probably because REH is showing us how Conan has changed, but mostly because Conan’s worried about tracking that jewel and saving his kingdom.

Howard: And it’s not a frying pan to fire kind of Burroughsian plotting, which, while fun, can grate a little. There’s more to it than that, probably because REH is showing us how Conan has changed, but mostly because Conan’s worried about tracking that jewel and saving his kingdom.

Bill: While Conan’s convincing disguise as a mercenary Free Companion is enough to get him into the fortress of Count Valbroso and within inches of grabbing the jewel, it is his old mantle of Amra the Lion that proves more valuable, and integral to the plot. Renewing old contacts with a corrupt and powerful Messantian merchant, Conan, as Amra, barachan pirate and scourge of the sea lanes, is at first betrayed, waylaid, and then pressed into service on the Venturer, a trading galley. This is a familiar situation for anyone who has been reading these tales thus far, and Conan turns the tables on his captors with the aid of the enslaved rowers, many of whom recognize him from his pirating days — and all of whom know him by reputation. It’s a triumphant moment, one that echoes but magnifies similar events in past tales, such as the end of “Iron Shadows in the Moon.” But here such echoes have an even greater weight because they contribute to the ongoing narrative, moving it ever forward.

The climax of Conan’s hunt for the Heart of Ahriman occurs in Stygia, land of ancient evil. Beneath a pyramid of black stone Conan hunts the jewel, though first he escapes the clutches of a beautiful, ageless vampire, Akivasha. Again and again we see Conan tempted in various ways in The Hour of the Dragon, but he refuses all such offers, whether they be to ride off and resume his mercenary wandering, take his newly won ship and turn the seas crimson with his piracy, carve out a new kingdom at the head of the armies of Poitain, or live forever at the side of a creature of flawless beauty. The man who once espoused a live-for-today philosophy in “Queen of the Black Coast” has been tempered by duty, his own honor lending a larger purpose to his existence. Thus, King Conan may slide easily back into the world of his wandering days, but he cannot be, as he once was, truly content in such an existence, not, at least, while his duties remain unresolved.

Howard: That’s a truly important point, especially for those who seem to feel that Conan never changes, or that every adventure is the same. I don’t know how anyone could ever argue that he’s a cardboard figure, for he’s a different man in “The Tower of the Elephant” than he is in “The Phoenix on the Sword,” two stories written very early on showing him at two stages of his life. His perspective on life changes and matures. It’s surely evident here. You’re absolutely right to point out how he’s tempted to slide back into his old ways, or to take an easier, more seductive path, yet he holds true to himself.

Howard: That’s a truly important point, especially for those who seem to feel that Conan never changes, or that every adventure is the same. I don’t know how anyone could ever argue that he’s a cardboard figure, for he’s a different man in “The Tower of the Elephant” than he is in “The Phoenix on the Sword,” two stories written very early on showing him at two stages of his life. His perspective on life changes and matures. It’s surely evident here. You’re absolutely right to point out how he’s tempted to slide back into his old ways, or to take an easier, more seductive path, yet he holds true to himself.

Bill: Khemi, in Stygia, is skillfully evoked in this section of the novel, the oppressive vegetation, the colossal buildings that crush the human spirit. Giant snakes, embodiments of the god Set, feed on the hapless, prostrate citizens of Stygia much as the malignant Thog feasted on the dreamers in “Xuthal of the Dusk.” Conan, of course, is an old hand at killing giant snakes, Stygian or otherwise. His herpecide provokes an angry mob — the willing slaves of Stygia’s priestly caste turning on one who would dare put his life before the dictates of the cult.

Howard: I’d say that this is one of my favorite segments in the book except that the whole book is so strong. Still, the thought of those giant snakes wandering the city and being sacred is pretty grotesque and creepy and inspired. It feels plausible enough that some human society might have thought it a “good” idea… I love how Conan deals with it exactly like we would want to deal with the thing, assuming we had his power and a handy sword.

Bill: The final conflict for possession of the jewel occurs deep underground, in a vaulted tomb overlooked by hundreds of masked dead. The priest Thutothmes seeks to supplant Stygia’s ruler Thoth-Amon, prerequisite to world-conquest, with the aid of an army of the resurrected dead — the irony that Thoth’s previous failure to kill King Conan in “The Phoenix on the Sword” possibly saves his reign from the renegade priest is a fine one. But Conan does not kill Thutothmes, who instead dies at the hands of the Khitan assassins set on Conan’s trail by the usurper Valerius. The Black Hand of Set facing off against the grim wielders of staves cut from the “living Tree of Death” — memorable inventions from REH, who wastes no opportunity throughout the novel to add colorful, fantastic details.

Bill: The final conflict for possession of the jewel occurs deep underground, in a vaulted tomb overlooked by hundreds of masked dead. The priest Thutothmes seeks to supplant Stygia’s ruler Thoth-Amon, prerequisite to world-conquest, with the aid of an army of the resurrected dead — the irony that Thoth’s previous failure to kill King Conan in “The Phoenix on the Sword” possibly saves his reign from the renegade priest is a fine one. But Conan does not kill Thutothmes, who instead dies at the hands of the Khitan assassins set on Conan’s trail by the usurper Valerius. The Black Hand of Set facing off against the grim wielders of staves cut from the “living Tree of Death” — memorable inventions from REH, who wastes no opportunity throughout the novel to add colorful, fantastic details.

Howard: It might be that everything in Stygia is “my favorite bit” from the novel, although they wouldn’t be as strong standing without the rest of the support structure. Here the hero descends into the underworld, facing the dead, and evil wizards, and the alluring vampiress, who is death and sex incarnate, and a powerful symbol of abdication of his true journey. It’s attractive to lose himself in passion and death, to not try to do the hard thing, the right thing, but Conan moves on. And Robert E. Howard paints the events in Stygia, both aboveground and below, so skillfully, that scene piles on scene, splendid and terrifying, at breakneck pace.

Bill: The final, culminating section of The Hour of the Dragon leaves Conan and the jewel on the deck of the Venturer while returning to the conspirators and Xaltotun, moving away from Conan’s point of view through time and space in a choice that once again proves REH’s storytelling instincts. REH could have followed Conan through his return to Aquilonia, his military preparations, his handing over of the jewel to the priests of Asura. Instead, these things happen off stage, and we once again see Conan through the eyes of the conspirators just as we had in the opening sequence of the novel. It’s marvelously effective, elevating Conan’s stature and enhancing his menace, setting the stage for several dramatic revelations, and keeping the forward momentum going without pause.

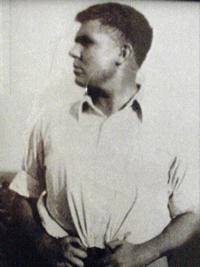

Robert E. Howard

Howard: He’s incredibly sure-footed, isn’t he? Instead of showing us Conan fretting, wondering what the enemies are doing, we instead see the enemies fretting, and wonder ourselves what Conan might be doing. REH understood that Conan was far more interesting than his villains, and that it would be a lot more fun to be kept in the dark, like the villains. It’s also a way to cut out the boring micromanaging from the narrative. Why follow Conan around as he talks to various allies and lays out his plan? This is much more entertaining.

Bill: The novel has it’s climax in battle, and here, again, REH shines. Battles in the Conan stories have always been well-portrayed, balancing exciting action with plausible strategy and clear narrative. But they have always been somewhat condensed, as the length of a short story dictates — resembling somewhat the Battle of the Valkia at the beginning of the novel, as dictated to Conan by a squire. But the Battle of the Valley of the Lion that caps The Hour of the Dragon is a multi-chapter, multi-scene extravaganza in which the conspirators each meet their doom. Valerius, lead into ambush by those he ruined, Amalric slain on the field by Conan’s lieutenant Pallantides, Xaltotun defeated in the midst of a planned human sacrifice by the witch and the priest of Asura, the latter armed with the Heart of Ahriman itself. A lot happens, but at no point is it disorienting, one section leading naturally to the next with clarity and undeniable momentum.

Howard: Right! Everybody gets their moment in the sun, or, more aptly, their just desserts.

Howard: Right! Everybody gets their moment in the sun, or, more aptly, their just desserts.

Bill: Tarascus, King of Nemedia, the Dragon whose hour has come and gone, is the last of the conspirators to fall, and he meets his fate at the hands of his fellow king. Conan, a man who kills without a moment’s hesitation, spares Tarascus’s life. And here we see Conan emerge fully as a King — while he takes the assault on his kingdom very personally, he does not put his personal interests over those of his people. He needs Tarascus alive to facilitate the withdrawal of Nemedia, and to level indemnities against that kingdom. The hot-headed barbarian who once gutted a man in the maw of Zamora for pushing him, is now the King who thinks three moves ahead. When he asks for Zenobia as ransom from Tarascus, he does so in the same breath as he asks for the other concessions due his kingdom. This is not a woman he intends to treat as a dalliance, this is his future Queen. The wanderer is now truly a King, the Lion will found a dynasty.

Howard: And this got touched upon in the comments last time, but I think it’s abundantly clear that Conan means to wed Zenobia. It’s been demonstrated multiple times at this point that he needs to establish a true line of succession, and a queen will give him an heir. Moreover, as Chris Hocking likes to point out, by God, Conan declares he’s going to marry Zenobia in front of his troops. Conan almost always says exactly what he means. To assume he’d have done something else seems to suggest a fundamental disconnect of a crucial aspect of his personality, or, at least, his maturation.

Howard: And this got touched upon in the comments last time, but I think it’s abundantly clear that Conan means to wed Zenobia. It’s been demonstrated multiple times at this point that he needs to establish a true line of succession, and a queen will give him an heir. Moreover, as Chris Hocking likes to point out, by God, Conan declares he’s going to marry Zenobia in front of his troops. Conan almost always says exactly what he means. To assume he’d have done something else seems to suggest a fundamental disconnect of a crucial aspect of his personality, or, at least, his maturation.

Once again, I think we could have covered this in even more detail. There are any number of lovely passages and grand moments that we’ve only touched on, or overlooked, but this post is on the long side already. I’ll summarize by saying that Bill and I came away from our re-read of this one with an even greater appreciation of Robert E. Howard as a writer. What a grand fantasy novel. We touched on this last week — there was NOTHING remotely like it for decades. Howard was an innovator, something that is overlooked far too often. And, unlike many short story writers turned novelists, his first and only fantasy novel works brilliantly. Would that we lived in a world where he’d gone on to write many more of them.

Next week, join us as we read through another long one, “A Witch Shall be Born.” And don’t forget to join us Monday on Leigh Brackett’s birthday to discuss “The Moon that Vanished.” You can pick up a really affordable copy at BAEN. (Details on the read through and a book link are here.)

November 30, 2015

Celebrating Leigh Brackett

The 100th birthday of the late, great Leigh Brackett is coming up next Monday, and to celebrate, Bill Ward and I our doing a read-through of one of her great stories set on a Venus that never was.

The 100th birthday of the late, great Leigh Brackett is coming up next Monday, and to celebrate, Bill Ward and I our doing a read-through of one of her great stories set on a Venus that never was.

Brackett was a phenomenal writer. She’s been called the Queen of Space Opera, but I think a better-named crown was probably Queen of Planetary Adventure.

She wrote screenplays with Faulkner AND mentored Ray Bradbury AND wrote the first draft of The Empire Strikes Back. She was writing about heroes who would have been comfortable plying the space lanes beside Han Solo and Malcolm Reynolds decades before those characters were ever conceived. Most importantly, though, she was simply an incredibly gifted adventure writer who wrote with fantastic atmosphere, wonderful pacing, and dynamic characters. She’s one of my very favorite writers, and she’s had a tremendous influence that (unfortunately) has often gone unsung.

We hope you’ll join in our re-read. To make things extra simple, here’s a link to an extremely affordable e-collection of her work from BAEN, . From that collection Bill and I will be reading “The Moon that Vanished.”

This e-book is only $4.00, and I have to say, if you’re going to invest that, you probably ought to simply get Brackett’s collection for $20.00 so you can read her even more (and justly) famed stories set on Mars. Bill and I are reading “The Moon that Vanished” because it’s a great one that gets passed over because she has so many more stories set on Mars.

Anyway, hope to see you here, and I hope you’ll trust my recommendation if you’ve never read Brackett.

November 27, 2015

Conan Re-Read: The Hour of the Dragon, Part 1

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing the first nine chapters of “The Hour of the Dragon.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are continuing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing the first nine chapters of “The Hour of the Dragon.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill: Last week we looked at the excellent “The People of the Black Circle,” a tale that sees REH growing as a writer and the Conan saga itself expanding in terms of the kinds of stories it can tell. This week we start our discussion of the one and only Conan novel, The Hour of the Dragon, a tale more than twice as long as its predecessor. While, as a commenter pointed out last week, “Black Circle” is described as a novel in its Weird Tales serialized release, The Hour of the Dragon is a true novel in our contemporary sense of the term, both in regards to sheer word count (73,000 words), and in its scale and structure. It is REH’s only completed novel and, as such, to me at least, represents a universe of lost potential from a writer who was clearly capable of mastering the novel form just as he had the short story.

Bill: Last week we looked at the excellent “The People of the Black Circle,” a tale that sees REH growing as a writer and the Conan saga itself expanding in terms of the kinds of stories it can tell. This week we start our discussion of the one and only Conan novel, The Hour of the Dragon, a tale more than twice as long as its predecessor. While, as a commenter pointed out last week, “Black Circle” is described as a novel in its Weird Tales serialized release, The Hour of the Dragon is a true novel in our contemporary sense of the term, both in regards to sheer word count (73,000 words), and in its scale and structure. It is REH’s only completed novel and, as such, to me at least, represents a universe of lost potential from a writer who was clearly capable of mastering the novel form just as he had the short story.

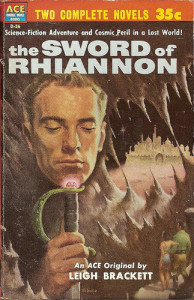

Howard: This is my third time reading the book, and I think I was even more impressed than I was the first. Robert E. Howard was at the top of his game when he wrote it. For decades there was nothing with which to compare this novel on an apple to apple basis because it was so far ahead of what anyone else had done. And then, of course, any direct genre comparison — by which I mean another sword-and-sorcery novel, not merely a fantasy novel — was probably generated after the author read The Hour of the Dragon. The closest we got in any of the decades following was probably Leiber’s The Swords of Lankhmar, which isn’t REALLY a complete novel — it’s more like a fix-up of two novelets, one closely following on the other. And while Swords may be entertaining, it’s not even the best Lankhmar story, let alone in danger of dethroning The Hour of the Dragon.

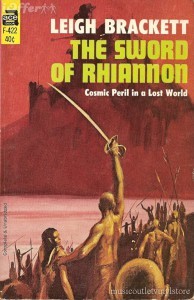

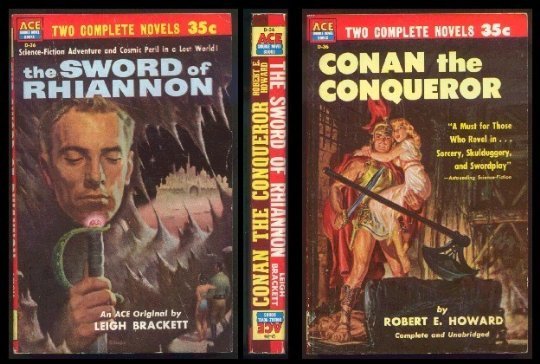

Probably the best ALMOST apples to apples comparison is with Leigh Brackett’s science fantasy/sword-and-planet The Sword of Rhiannon, with which The Hour of the Dragon was presented to the world in a mighty Ace Double book. Talk about a double A side! Still, though, Brackett wasn’t writing an honest-to-goodness sword-and-sorcery novel and she wrote it decades after Howard. No one else was to draft anything like it for years to come.

Probably the best ALMOST apples to apples comparison is with Leigh Brackett’s science fantasy/sword-and-planet The Sword of Rhiannon, with which The Hour of the Dragon was presented to the world in a mighty Ace Double book. Talk about a double A side! Still, though, Brackett wasn’t writing an honest-to-goodness sword-and-sorcery novel and she wrote it decades after Howard. No one else was to draft anything like it for years to come.

Bill: The novel that would come to be more popularly known as Conan the Conqueror in its Gnome Press and Ace/DeCamp incarnation was the result of a solicitation from a British publisher for a full-length pulp adventure from REH. The same publisher had previously expressed interest in a collection of shorter tales from REH, but had backed out citing lack of market interest in short fiction collections. REH, who had previously expanded the scope of his stories to include nearly every market and genre he had any proclivity to write in, was now about to expand in a different direction by making the leap to long form fiction.

Bill: The novel that would come to be more popularly known as Conan the Conqueror in its Gnome Press and Ace/DeCamp incarnation was the result of a solicitation from a British publisher for a full-length pulp adventure from REH. The same publisher had previously expressed interest in a collection of shorter tales from REH, but had backed out citing lack of market interest in short fiction collections. REH, who had previously expanded the scope of his stories to include nearly every market and genre he had any proclivity to write in, was now about to expand in a different direction by making the leap to long form fiction.

After an abortive stab at the planetary romance novel Almuric, left unfinished by REH and possibly later completed by his agent, Otis Aldebert Kline, REH turned again to the Cimmerian and his Hyborian landscapes. And it is to King Conan, whom we have not seen since “The Scarlet Citadel,” that REH returns to for his epic. Indeed, it’s “The Scarlet Citadel” itself that serves as the rough basis for the plot of The Hour of the Dragon, something that must have been very obvious to readers of the “chronological” Conan saga which published the two stories back-to-back.

Howard: Robert E. Howard scholar Morgan Holmes has a very convincing argument that it was actually Otto Binder (another of Kline’s writer clients) who finished Almuric, owing to certain stylistic similarities between Binder’s prose and the conclusion to Almuric, especially when comparing the “authorial imprint” on those sections to what Kline usually wrote. There may be no way to prove it completely, but Holmes converted me. Unfortunately, my Google-Fu hasn’t been able to turn up the discussion, but if memory serves, Binder was particularly focused upon scent as a sensory input, moreso than Kline or REH ever were (along with some other stylistic fingerprints). When you hold up those final bits next to what Kline or Binder wrote, the authorial voice is as clear as the shagreen pants Jehungir was wearing a couple of weeks back.

Howard: Robert E. Howard scholar Morgan Holmes has a very convincing argument that it was actually Otto Binder (another of Kline’s writer clients) who finished Almuric, owing to certain stylistic similarities between Binder’s prose and the conclusion to Almuric, especially when comparing the “authorial imprint” on those sections to what Kline usually wrote. There may be no way to prove it completely, but Holmes converted me. Unfortunately, my Google-Fu hasn’t been able to turn up the discussion, but if memory serves, Binder was particularly focused upon scent as a sensory input, moreso than Kline or REH ever were (along with some other stylistic fingerprints). When you hold up those final bits next to what Kline or Binder wrote, the authorial voice is as clear as the shagreen pants Jehungir was wearing a couple of weeks back.

Bill: Very interesting, I’ll have to reread Almuric now that I’ve read some Kline, though in no way is that book on the level of the one we are discussing. Roughly the first third of The Hour of the Dragon recalls the plot of “The Scarlet Citadel:” King Conan is betrayed and captured by conspirators aided by a powerful wizard, and his throne usurped by an Aquilonian nobleman. But, while these common elements are present, the novel itself enlarges upon them in every way possible. For instance, the quick set-up of Conan’s betrayal and capture on the battlefield in “Citadel” becomes the far more memorable and exciting chapter in Dragon that sees Conan, about to lead his forces in battle, paralyzed by sorcery and his place on the field taken by another, his army defeated by a magically-provoked landslide, and the king himself captured by a rival ruler and the resurrected wizard Xaltotun. It’s economical, compelling, and gives a great sense of character. It’s the kind of thing you see repeated a few times in this early part of the story — familiar elements are not simply just repeated here, they are re-imagined and reborn anew.

Howard: The opening sequence, when Xaltotun is called back, is immediately evocative and arresting. And there’re so many other excellent moments. There’s even a reason that Conan is kept alive this time, and not simply because the villain is waiting for the proper moment to slay him (i.e. the author needs an excuse to keep him alive). Xaltotun can use Conan as a pawn against the allies he doesn’t trust. And our favorite Cimmerian is in top form, battling on despite infirmities. He may be disturbed by Xaltotun, but he’s not cowed when he meets him.

Howard: The opening sequence, when Xaltotun is called back, is immediately evocative and arresting. And there’re so many other excellent moments. There’s even a reason that Conan is kept alive this time, and not simply because the villain is waiting for the proper moment to slay him (i.e. the author needs an excuse to keep him alive). Xaltotun can use Conan as a pawn against the allies he doesn’t trust. And our favorite Cimmerian is in top form, battling on despite infirmities. He may be disturbed by Xaltotun, but he’s not cowed when he meets him.

Bill: Yes! There is also an even more compelling reason for Aquilonia to think Conan dead, it’s stronger all around. The economy and efficiency of the earliest chapters are perhaps to be expected by a master practitioner of the short story, but one could easily imagine just the opposite emerging from a tight and fast writer attempting his longest work to date — namely verbosity and stretch. And it isn’t just economy of prose and structure, it’s subtle and brilliant choices that keep Dragon as tightly woven as a short story. For instance, REH concludes his opening chapter, which introduces the conspirators, the Heart of Ahriman, and Xaltotun, with a descriptive image of Conan viewed via sorcerous means. In one stroke we are introduced to the protagonist — REH no doubt having to assume that most of his potential audience would be meeting him for the first time — and we are also given a transition directly to the next chapter. But what the description also does is set up the contrast with what’s about to happen — the indomitable warrior-king will at first be rendered helpless, then he’ll be stripped of his kingship. The promise of Conan’s “reverting to type,” a theme that underlies the story, is established twice in lines that show him to be more warrior than aristocrat:

…but the great sword at his side seemed more natural to him than the regal accouterments…His dark, scarred, almost sinister face was that of a fighting-man, and his velvet garments could not conceal the hard, dangerous lines of his limbs.

Reading this, we understand the man in Chapter III who, paralyzed and weakened, makes an impossible stand against his foes, leaning against his tent pole and still summoning the strength to wield his sword. We could have been given this description in Chapter II, say from the point of view of the civilized Pallantides, but instead we get a more intense effect when we see Conan through the eyes of his enemies. Xaltotun, newly resurrected after three thousand years, immediately remarks that this Conan, clearly no Hyborian, is of a people he remembers all too clearly. A people that had never been conquered in his age as well.

Reading this, we understand the man in Chapter III who, paralyzed and weakened, makes an impossible stand against his foes, leaning against his tent pole and still summoning the strength to wield his sword. We could have been given this description in Chapter II, say from the point of view of the civilized Pallantides, but instead we get a more intense effect when we see Conan through the eyes of his enemies. Xaltotun, newly resurrected after three thousand years, immediately remarks that this Conan, clearly no Hyborian, is of a people he remembers all too clearly. A people that had never been conquered in his age as well.

Howard: It’s a fine moment in chapters that are rich with fine moments. You remarked to me how clever it was that the squire relates the battle that Conan can’t see. Much as of Shakespeare’s characters might tell us something that happened (or is happening) off stage, it’s done so skillfully that we’re held spellbound trying to imagine it, especially as we see Conan’s reaction. I’d actually forgotten poor Valannus perished, although you’d think after reading it twice before such a moment would have been indelibly etched in my brain.

Bill: It’s a smart way to not only save space — a full description of the battle could take another chapter — but it also keeps the attention firmly on Conan and builds toward the moment of his capture.

Bill: It’s a smart way to not only save space — a full description of the battle could take another chapter — but it also keeps the attention firmly on Conan and builds toward the moment of his capture.

Thematically, a story of King Conan allows an even greater layer of meaning to creep into the ongoing dialog REH is having about civilization and barbarism. Conan is shown to be a good king because of what kind of man he is, the son of a blacksmith without a drop of royal blood, a man whose moral code was forged in wild and savage lands. When the king, on the run from his captors, pursued by a spying raven, sees an old woman — one of his subjects — being led to a noose by four armored soldiers he does not hesitate to intervene. Indeed, the sight enrages him, for this woman, like all his subjects, is owed his protection as king. Had the woman herself not been a witch with her own ferocious lupine bodyguard, Conan would possibly not have survived the encounter. But the point of course is that Conan understands the reciprocal duties of command, lessons he learned as a pirate, bandit, and raider chieftain. But now that loyalty is not just extended to men who have bled by his side, but to an entire kingdom — Aquilonia and all of its people are his, but not as some mere possession, it and they are his responsibility. Contrast this to the conspirators and, in particular, to the Aquilonain usurper Valerius, and you can see that the self-contained honor of the barbarian (or, at least, this particular barbarian) forges a man of character worthy of the weighty responsibilities of the crown.

Howard: Indeed, and we later see that because Conan values his people, they return their loyalty. He expected nothing of the kind and was doing his duty to a subject when he saves the old woman, but he has “paid it forward,” for we later see how instrumental the witch is in turning the tide against the invaders. She also happens to point Conan toward his next objective. And let me step aside to discuss meta issues here: writers should pay close attention to the through line. At no point do we NOT KNOW why Conan is taking any of his actions. We always know exactly what Conan is doing, where he’s going, and why. There’s almost constant forward momentum, such that when it’s restrained (such as when Conan is held in the dungeon) we feel the same frustration as our protagonist to return to that forward progress.

Howard: Indeed, and we later see that because Conan values his people, they return their loyalty. He expected nothing of the kind and was doing his duty to a subject when he saves the old woman, but he has “paid it forward,” for we later see how instrumental the witch is in turning the tide against the invaders. She also happens to point Conan toward his next objective. And let me step aside to discuss meta issues here: writers should pay close attention to the through line. At no point do we NOT KNOW why Conan is taking any of his actions. We always know exactly what Conan is doing, where he’s going, and why. There’s almost constant forward momentum, such that when it’s restrained (such as when Conan is held in the dungeon) we feel the same frustration as our protagonist to return to that forward progress.

But returning to your point, I think Howard clearly shows us time and again Conan’s capability as both a king and general. His questions about the enemy forces were sharp and insightful, as you’d expect an experienced military leader would be, but then any intelligent tyrant could have noticed these things. Conan, in interacting with his subjects, demonstrates the compulsion toward duty and responsibility of the very best of rulers.

Bill: And, of course, Conan does not flee his endangered Kingdom even when he has the chance, just as a captive Conan refused earlier to cooperate with the men who took his crown away from him. Instead he rushes off to rescue yet another of his subjects, this time the beautiful Countess Albiona, a woman who refuses to be the lover of the usurper and is being held in the Iron Tower of Tarantia, Aquilonia’s capital. Conan demonstrates some of those roguish skills of his early adventuring days by infiltrating both city and tower in disguise. The scene of the rescue, where Conan doffs the executioner’s hood of his disguise and sets about to do an executioner’s work on the men holding the countess hostage, is a satisfying and bloody culmination to the first nine chapters of the novel.

Bill: And, of course, Conan does not flee his endangered Kingdom even when he has the chance, just as a captive Conan refused earlier to cooperate with the men who took his crown away from him. Instead he rushes off to rescue yet another of his subjects, this time the beautiful Countess Albiona, a woman who refuses to be the lover of the usurper and is being held in the Iron Tower of Tarantia, Aquilonia’s capital. Conan demonstrates some of those roguish skills of his early adventuring days by infiltrating both city and tower in disguise. The scene of the rescue, where Conan doffs the executioner’s hood of his disguise and sets about to do an executioner’s work on the men holding the countess hostage, is a satisfying and bloody culmination to the first nine chapters of the novel.

Howard: I loved that entire sequence. It’s immensely satisfying to see Conan triumph at that moment even though he has so many obstacles ahead of him still, and even though all of his foes yet remain alive.

As a final observation for the week, Zenobia is made of awesome. She could have been a weak throwaway character, especially with Howard introducing her as a woman who became enamored of Conan from afar. Left alone after meeting her, Conan shrugs, because beautiful women have risked their lives to aid him before. Yet, isolated as she is, and seeing only lesser men, is it really so strange that she should become fascinated with Conan when she hears about the same escapades that have thrilled all of us? She’s not a star-struck damsel in distress, she’s brave and possessed of “practical intelligence” as we see when she’s managed to sneak a useful dagger to Conan, rather than a pointless stiletto. She went to great pains to engineer an escape, complete with key and horse. Yes, she’s a looker, but it’s her bravery, intelligence, and resourcefulness on the fly that captures Conan’s loyalty, such that he’ll return to claim her as his bride by novel’s end. She has to alter her plans several times once things go awry, and still manages to get him out of Tarascus’ clutches.

As a final observation for the week, Zenobia is made of awesome. She could have been a weak throwaway character, especially with Howard introducing her as a woman who became enamored of Conan from afar. Left alone after meeting her, Conan shrugs, because beautiful women have risked their lives to aid him before. Yet, isolated as she is, and seeing only lesser men, is it really so strange that she should become fascinated with Conan when she hears about the same escapades that have thrilled all of us? She’s not a star-struck damsel in distress, she’s brave and possessed of “practical intelligence” as we see when she’s managed to sneak a useful dagger to Conan, rather than a pointless stiletto. She went to great pains to engineer an escape, complete with key and horse. Yes, she’s a looker, but it’s her bravery, intelligence, and resourcefulness on the fly that captures Conan’s loyalty, such that he’ll return to claim her as his bride by novel’s end. She has to alter her plans several times once things go awry, and still manages to get him out of Tarascus’ clutches.

Bill: She’s great — had she picked a prettier dagger, Conan would have been ape food. And she, as Conan’s future bride, also reminds me of my final point, the obverse of Conan’s barbarian roots supplying his strength as a king, and that’s Conan’s weakness as a dynast. Several times it is mentioned that Conan’s lack of an heir has undermined his position, for there is no one to rally behind after his apparant death. Conan’s conversation with his loyal supporter Servius brings up very realistic points about the usurper’s ability to rule the country, how Conan’s potential army is too dispersed to be of use, and the importance of royal blood. Indeed, Conan realizes that no amount of power of his is equal to Valerius’s nobility and birth in this instance, and I think it’s the final lesson he has to learn to be a true king. His self-contained, wandering spirit must instead lay a solid foundation if he is to serve his people, his sword alone can never be enough to hold a country together.

Bill: She’s great — had she picked a prettier dagger, Conan would have been ape food. And she, as Conan’s future bride, also reminds me of my final point, the obverse of Conan’s barbarian roots supplying his strength as a king, and that’s Conan’s weakness as a dynast. Several times it is mentioned that Conan’s lack of an heir has undermined his position, for there is no one to rally behind after his apparant death. Conan’s conversation with his loyal supporter Servius brings up very realistic points about the usurper’s ability to rule the country, how Conan’s potential army is too dispersed to be of use, and the importance of royal blood. Indeed, Conan realizes that no amount of power of his is equal to Valerius’s nobility and birth in this instance, and I think it’s the final lesson he has to learn to be a true king. His self-contained, wandering spirit must instead lay a solid foundation if he is to serve his people, his sword alone can never be enough to hold a country together.

Howard: Nicely reasoned! Well, we could probably go on for another few thousands words — we just touched on the ape fight — but that leftover turkey’s not going to eat itself. Next week we’ll finish our read through of The Hour of the Dragon, starting with chapter 10. Hope to see you here!

November 20, 2015

Conan Re-Read: “The People of the Black Circle”

Bill Ward and I are starting our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The People of the Black Circle.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are starting our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Bloody Crown of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The People of the Black Circle.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill: It’s easy to see why “The People of the Black Circle” is a Conan fan-favorite: plot-twists and action galore, great supporting characters, an exotic but plausibly constructed setting, and fabulous villains using a host of inventive magic. Conan is the adventurer and rogue we’ve come to know over the last dozen or so stories, this time commanding a tribe of Afghuli raiders on the borders of Vedhya, the Hyborian Age equivalent of India. There are a few elements in the story that may recall others in the Conan saga, but this time around there is nothing that feels recycled or borrowed, indeed the whole story feels fresh and something of a departure from what has come before.

Bill: It’s easy to see why “The People of the Black Circle” is a Conan fan-favorite: plot-twists and action galore, great supporting characters, an exotic but plausibly constructed setting, and fabulous villains using a host of inventive magic. Conan is the adventurer and rogue we’ve come to know over the last dozen or so stories, this time commanding a tribe of Afghuli raiders on the borders of Vedhya, the Hyborian Age equivalent of India. There are a few elements in the story that may recall others in the Conan saga, but this time around there is nothing that feels recycled or borrowed, indeed the whole story feels fresh and something of a departure from what has come before.

Howard: It was a grand adventure and a very different feel from the last little parcel of tales. I’m glad REH decided to vary his theme, and I’m scratching my head wondering why this story didn’t serve more often as a sword-and-sorcery template. Probably because its unique character made it far more difficult to imitate.

Bill: “The People of the Black Circle” is a true novella in structure, and at no point does it feel stretched or thinned-out just to pad the length. Patrice Louinet states, in his second installment of the Hyborian Genesis essay in The Bloody Crown of Conan, that much has been made over REH being inspired by Talbot Mundy for this particular story, though no real evidence supports this. To me, this novella feels somewhat like Harold Lamb’s longer works of adventure fiction, a writer REH was clearly influenced by — possibly in a very direct and recent sense, given (our) Howard’s suspicion last week over the word ‘shagreen’ being used in “The Devil In Iron.” Could REH have been re-reading some Lamb and using him for inspiration during this phase of his Conan chronicling?

Bill: “The People of the Black Circle” is a true novella in structure, and at no point does it feel stretched or thinned-out just to pad the length. Patrice Louinet states, in his second installment of the Hyborian Genesis essay in The Bloody Crown of Conan, that much has been made over REH being inspired by Talbot Mundy for this particular story, though no real evidence supports this. To me, this novella feels somewhat like Harold Lamb’s longer works of adventure fiction, a writer REH was clearly influenced by — possibly in a very direct and recent sense, given (our) Howard’s suspicion last week over the word ‘shagreen’ being used in “The Devil In Iron.” Could REH have been re-reading some Lamb and using him for inspiration during this phase of his Conan chronicling?

Howard: At this point REH was enough of his own man that very little of another author’s style is obvious in his fiction. A few of his earlier histories bear an obvious Lamb imprint, but after that, it’s just surface details or atmosphere that he’s pulled from another writer (like “shagreen” last week). The idea that this story is inspired in part by Mundy has to do an awful lot with Mundy’s fiction in Adventure magazine, which dealt with the Khaiber pass, and Afghans, and daring deeds. Mundy and Lamb are generally regarded as the best writers Adventure magazine printed, although naturally there are some who would disagree, and that’s not to say that there weren’t some other quite excellent writers who appeared in its pages. It was chock full of great stories and I bet almost all of our regular readers would have been eagerly reading it every couple of weeks had we been alive back in its day.

REH actually mentioned Mundy in his correspondence more often than he mentioned Lamb. (If you’re curious about Lamb, Mundy, and Adventure, I discuss them in detail here, and of course Lamb in greater detail in all kinds of places, most recently here, which includes some excerpts.)

REH actually mentioned Mundy in his correspondence more often than he mentioned Lamb. (If you’re curious about Lamb, Mundy, and Adventure, I discuss them in detail here, and of course Lamb in greater detail in all kinds of places, most recently here, which includes some excerpts.)