Howard Andrew Jones's Blog, page 38

November 11, 2015

Podcast Guest

Last week I dropped by The Once and Future Podcast to talk writing, gaming, Harold Lamb and other assorted fiction and nerd stuff with the incomparable Anton Stout. We had a great chat, and it’s a shame that Patrick Rothfuss has a hit out on him, because I’d like to get to know him better.

Last week I dropped by The Once and Future Podcast to talk writing, gaming, Harold Lamb and other assorted fiction and nerd stuff with the incomparable Anton Stout. We had a great chat, and it’s a shame that Patrick Rothfuss has a hit out on him, because I’d like to get to know him better.

Anyway, the podcast is here. Hopefully I didn’t ramble too much. I talked a little about Dabir and Asim and my new Pathfinder novel, and a little about my writing process, and a little about my upcoming new series, and other things about gaming. And maybe I talked too much. Sometimes you give me a mic and I just won’t shut up…

November 9, 2015

Hard Writing Lessons 3

I’m moving some older posts over from my original LiveJournal blog to this one, and ran across a long list of Hard Writing Lessons from 2007! Apparently I’d just turned over a manuscript to some beta readers and came back from the experience slapping my forehead. They found all kinds of problems. I don’t remember what they were, but I remember my profound sense of shame.

I’m moving some older posts over from my original LiveJournal blog to this one, and ran across a long list of Hard Writing Lessons from 2007! Apparently I’d just turned over a manuscript to some beta readers and came back from the experience slapping my forehead. They found all kinds of problems. I don’t remember what they were, but I remember my profound sense of shame.

I THINK it was probably a novel that’s no longer in circulation, because 2007 pre-dates The Desert of Souls. Anyway, here’s a long note from younger Howard that still reads like good advice. I was pretty disappointed in myself when I wrote it! Clearly I hadn’t learned that other lesson yet, which is to be kind to yourself.

I’ve included a little bit of the preamble:

… I realize that all writers have different strengths and weaknesses, so a lot of this may not apply to you. It’s a list I wrote for me, and the issues I’m dealing with in my novel-in-progress at this time. I’ll post it here in the hope someone else can find my hard lessons instructive. I hope that I have the wisdom to do so myself!

Get lemons, make lemonade. Get tribble?

Know what every character in the scene wants before you start writing.

Your longer works need DETAILED outlining. Always. You can work out plot problems, motivation, etc. in a rich outline so you don’t waste time writing, and rewriting, and rewriting just to get the structure right. As you’ve been doing… Have you noticed how painful that is yet?

If you have to start inventing scenes for a POV character you probably don’t NEED that POV character… refer to point 2, because if you’d outlined properly before writing you’d probably have noticed you had nothing for that POV character to do later on.

Remember how you’re supposed to give your story a clear through line? Really? Then write that way. The character HAS to have a driving goal that both she and the reader know. And it should be one that can be easily summarized: Indy’s looking for the headpiece to the staff of Ra so he can find the Ark of the Covenant.

Don’t coast. When revising, what was once the best scene in the earlier draft may not hold up any more. Look at it critically.

Puny Banner poses beside Hulk’s Car.

If you find a flaw and try to excuse it through character dialogue just so you can leave some scenes the way they are… you’re going to regret it. You need to look at that flaw from another angle. It will probably entail changing some scenes, threads, character arcs, or other painful things. Suck it up and make the changes.

Sometimes it is more important to spend all of a day’s writing time contemplating the story than worrying about how many words you get down – remembering this will help you overcome point 6. Quality, not quantity. You do NOT work best to set word counts. Remember that.

Remember those episodes of The Next Generationyou hated because it felt like they would have a moment of character interaction that had NOTHING to do with the rest of the story? It drove you nuts that it wasn’t interwoven with the plot. NEVER do that. If you feel like the reader needs to know something about the character, don’t jam it in, just keep it in mind and it should come out, eventually, if your characters are well-envisioned. Refer again to point 2.

It’s great that you know what happened during the entire boring scene, but you can summarize it. More likely you’re doing number 8, though, which seems to be your new secret weakness, and means that the scene doesn’t need to be summarized so much as completely freakin’ REMOVED.

You tend to think that once you understand something that you’ve learned it. By this time you should know better. Continue to refer to this list, because if you’d really learned all this stuff you wouldn’t have had to write this list in the first place.

November 6, 2015

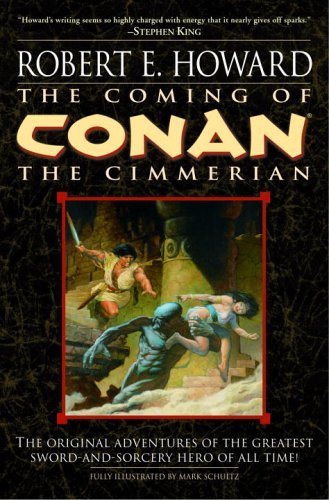

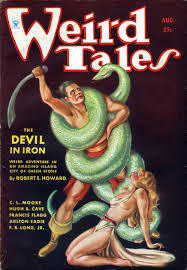

The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “The Devil in Iron”

Bill Ward and I are finishing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The Devil in Iron.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are finishing our read through of the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The Devil in Iron.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill: One thing that struck me as fresh with “The Devil In Iron,” a story that reprises many familiar elements from the last handful of Conan stories, is that an antagonist’s plan to kill Conan is what sets the plot in motion. We haven’t seen that in a story since “The Phoenix on the Sword” and “The Scarlet Citadel,” two King Conan yarns where his importance to the larger Hyborian world is undeniable.

Howard: I ended up liking this one more than I was afraid I was, because I’d recalled that it was sort of a fix-up of elements we’d seen before. I do wish we saw more of Conan being a Kozak and having Kozak adventures, but, alas, we only hear about it and see his outfit.

Harold Lamb was one of Robert E. Howard’s favorite writers and you can see his influence upon Howard, most especially in his historicals (I wrote about this extensively in the concluding essay in the Del Rey historical volume of Robert E. Howard fiction, Sword Woman). But you usually don’t see Lamb influence in the Conan stories… except for here. Did you notice the word “shagreen?” It hasn’t appeared in any Conan stories until this one, where it crops up at least three times. It’s a word Lamb employed to describe a kind of boot texture his Cossack characters wore.

Harold Lamb was one of Robert E. Howard’s favorite writers and you can see his influence upon Howard, most especially in his historicals (I wrote about this extensively in the concluding essay in the Del Rey historical volume of Robert E. Howard fiction, Sword Woman). But you usually don’t see Lamb influence in the Conan stories… except for here. Did you notice the word “shagreen?” It hasn’t appeared in any Conan stories until this one, where it crops up at least three times. It’s a word Lamb employed to describe a kind of boot texture his Cossack characters wore.

Note also the name Jehungir and, of course, the word kozak, and the description of the kozak camp on the river and other cossack terminology. All of these are likely, though not definitively, from Lamb (Howard might have been reading about Cossacks and an emperor named Jehangir from other source, although both were beloved by Lamb). It’s rather a superficial influence compared to some of that found in the historicals, but it’s there.

Bill: Very cool, I hadn’t made the connection but it’s obvious now. We’ve heard mention of Conan as a kozak in previous tales, but in “The Devil In Iron” Conan is actually the commander of the freebooters, and could be said to be a kind of king and an important player in the region of Hyrkania and Turan. In “The Scarlet Citadel” King Conan is trapped and captured because of a betrayal of alliances. In this story, pirate Conan is lured into a trap on a remote island in the Vilayet Sea, drawn there by the promise of a buxom beauty.

Bill: Very cool, I hadn’t made the connection but it’s obvious now. We’ve heard mention of Conan as a kozak in previous tales, but in “The Devil In Iron” Conan is actually the commander of the freebooters, and could be said to be a kind of king and an important player in the region of Hyrkania and Turan. In “The Scarlet Citadel” King Conan is trapped and captured because of a betrayal of alliances. In this story, pirate Conan is lured into a trap on a remote island in the Vilayet Sea, drawn there by the promise of a buxom beauty.

After an opening in which the supernatural juggernaut of the title is teased, we are treated to an outline of the plot to catch Conan on the very same island where we’ve just seen an ancient evil reborn. “The Devil in Iron” is heavily reminiscent of “Iron Shadows in the Moon” and “Xuthal of the Dusk,” but most especially the former of those two recent stories. Patrice Louinet, in his “Hyborian Genesis” essay at the back of The Coming of Conan, mentions the fairly large time gap between the writing of “The Vale of Lost Women” and this story, with “The Devil in Iron” serving as a way for REH to get back up to speed with the Cimmerian. The story is a fitting capstone to this collection of the first Conan tales, being one more of the ‘formula’ stories, but also one of the best of those.

Howard: I think it’s definitely a tick up, even with some repeated themes. I thought that the history conveyed in a dream called back to “Queen of the Black Coast” and that the opening of the lone man awakening a powerful being of pre-history was similar to the opening to “Black Colossus.”

Howard: I think it’s definitely a tick up, even with some repeated themes. I thought that the history conveyed in a dream called back to “Queen of the Black Coast” and that the opening of the lone man awakening a powerful being of pre-history was similar to the opening to “Black Colossus.”

Bill: Absolutely, there is a lot of revisiting tried and true elements in this story. Like in “Iron Shadows,” here Conan explores the ruins of a mysterious island in the Vilayet Sea while a supernatural evil bides its time. But the ruins Conan finds on Xapur have been newly rebuilt, the entire city and its people reborn in the dream of an awakened demi-god from the dawn of time — and, as in “Xuthal,” which the story mentions directly in comparison, the city dreams its ancient dream at the whim of a malign master.

Howard: I liked that reference to Xuthal. It’s something we don’t often see in the Conan stories. It’s neat when Conan himself refers to things that have happened before.

Bill: Me too, I was pleased to see it and would have liked to see more references like that between the stories. Despite recycling some elements, “Devil In Iron” works just fine as its own story, especially once we get all the set-up out of the way and Conan is tearing through the dreaming city with an indestructible god on his heels. In some ways many of those reused elements from other stories are used to better effect here — the “iron devil” himself, Khostal Kel, is much more interesting and integrated into the story than the “iron shadows” of a previous tale. The use of a special or magical weapon to defeat him is something I don’t think we’ve seen before, though it is of course a very common trope in modern fantasy.

Bill: Me too, I was pleased to see it and would have liked to see more references like that between the stories. Despite recycling some elements, “Devil In Iron” works just fine as its own story, especially once we get all the set-up out of the way and Conan is tearing through the dreaming city with an indestructible god on his heels. In some ways many of those reused elements from other stories are used to better effect here — the “iron devil” himself, Khostal Kel, is much more interesting and integrated into the story than the “iron shadows” of a previous tale. The use of a special or magical weapon to defeat him is something I don’t think we’ve seen before, though it is of course a very common trope in modern fantasy.

And while “The Devil In Iron” doesn’t give us too much in the way of REH’s barbarian versus civilization debate, it does posses some interesting elements and themes that tie in with it. One thing I noticed was that Conan was twice nearly overwhelmed by Khostal Kel’s strange visions of the past — and both times it was Octavia that pulled him out. Once it was her weeping that snapped the Cimmerian out of the black-lotus-like vision of the past that was destroying his sanity, and the second time it was her shouting in fear after Conan defeated the demi-god but was, again, in danger of losing his mind. Whether intentional or not, it certainly seems fitting that the very real charms of a lovely young woman, something as rooted in the reality of the physical self as is possible to be, is what drives the Lovecraftian madness away from our hero’s mind.

Overall “The Devil In Iron” feels in some ways like the remix of a favorite song, it’s old familiar territory that’s well worth traipsing through again, and a welcome return to form after last week’s “The Vale of Lost Women.” From this point on the stories get much longer, the plots more involved, and REH’s inspirations shift in new directions. It’s a fitting place to end the first of Del Rey’s Conan collections, The Coming of Conan.

Overall “The Devil In Iron” feels in some ways like the remix of a favorite song, it’s old familiar territory that’s well worth traipsing through again, and a welcome return to form after last week’s “The Vale of Lost Women.” From this point on the stories get much longer, the plots more involved, and REH’s inspirations shift in new directions. It’s a fitting place to end the first of Del Rey’s Conan collections, The Coming of Conan.

Howard: All fairly said. Maybe it’s lighter Conan, but it’s still pretty tasty and delivers some fine moments.

Next week we’ll talk a little about what lies ahead and before too much longer we’ll plunge into the rest of the Conan stories, most of which, as Bill pointed out, are longer than what’s come before. Hope to see you here.

November 4, 2015

Hard Writing Lessons 2

If it bores you, it’s probably going to bore your readers.

If it bores you, it’s probably going to bore your readers.

While this is absolutely true in my experience, I’ve only recently developed a good strategy to fight this particular problem. (And no, I don’t usually hear that my books are stuffed full of boring scenes — I’ve just cut them, painfully, after lavishing attention on them.)

The trick is knowing when you’re having trouble because you just don’t feel like writing and when you’re having trouble because you’re bored with the scene. Unfortunately, when I was just beginning to develop the discipline to write I sometimes had to force myself to work even when I didn’t feel like it.

I really don’t have to do that anymore, yet I still get to scenes sometimes that are excruciating to draft. They look good on my outline and they SEEM like they’re going to be interesting, but when I get to them I find I’m constantly distracted or thinking about something else. When that happens, the writing doesn’t flow and my word count drops precipitously.

I really don’t have to do that anymore, yet I still get to scenes sometimes that are excruciating to draft. They look good on my outline and they SEEM like they’re going to be interesting, but when I get to them I find I’m constantly distracted or thinking about something else. When that happens, the writing doesn’t flow and my word count drops precipitously.

The problem is further exasperated because every now and then I think most writers have bad writing days that just need to be worked through. Just last week I spent the better part of a day digging into a scene I thought I needed. Having just taken a long trip, I thought I was feeling tired and having trouble focusing, which was especially frustrating because I had extra time to write all week long.

After working one afternoon and then most of a morning with the scene I suddenly realized how much more I was looking forward to the one that came after and, tired though I was, when I switched, the next bit was fun and flowed.

So how do you tell?

That’s the tricky part, because when you’re still apprenticing you may need to make yourself write or stick with a scene to the end. I used to skip around the prose and never finish anything.

If you routinely finish things and don’t have to struggle to get your scenes and chapters done, then consider the following.

Ask yourself what’s absolutely vital in the scene. If nothing is, don’t bother with it.

If there ARE vital bits, then you can either re-envision the scene until you find it interesting OR find a way to get that information into other scenes.

Try writing the scene you’re really interested in. You can always come back to the problem scene later, maybe with better perspective on how to handle it.

Elmore Leonard once wrote that “I try to leave out the scenes that people skip.” Do that.

November 2, 2015

Hard Writing Lessons 1

This being the first full week of National Novel Writing Month, I thought I’d start posting some of my hard learned writing lessons. One of these years I hope to join in, but once again I’m actually wrapping one up (last year I was feverishly revising one, and I think that was the case for the two years prior).

This being the first full week of National Novel Writing Month, I thought I’d start posting some of my hard learned writing lessons. One of these years I hope to join in, but once again I’m actually wrapping one up (last year I was feverishly revising one, and I think that was the case for the two years prior).

Regular visitors to the site, or any who’ve heard me speak in public, know that I like to repeat the lesson I found hardest to learn: know what every character wants before you start writing the scene. I still remind myself of that before I ever get to work.

There’s more to it than what I’ve usually said, but for those of you who’ve not read my previous comments before, let me first explain. Imagine you’re a film or stage director. Before you send your players out to give their lines you have to provide them with motivation. A good actor will want to know their background and their goals and why they’re in their particular emotional state. I find that if I remind myself of this rule before every scene it saves me a lot of headache and means a lot less rewriting — and means I throw out a lot fewer scenes.

But there’s more, as my astute wife recently pointed out to me. She’s been reading the rough draft of my newest and had several suggestions for fleshing it out. It all boil down to knowing the environment the characters were living in, because it informs their actions. If, for example, your characters are avoiding the main trade route for fear of being found by other travelers, it’s not enough to know how often patrols are supposed to turn up. Who else travels the road? What goods do they bear? What important cities are there along the way?

Sure, its just window dressing unless said cities at the end of the road are crucial to the plot. But that knowledge makes the world more real. Your characters are apt to be thinking of these things as they travel to contemplate their best moves.

Of course, don’t use these details for info dumping. It might be that the info YOU know about the background will never come to light. But it will inform the behavior of your characters, hence its connection to knowing what your characters want.

October 30, 2015

The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “The Vale of Lost Women”

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The Vale of Lost Women.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “The Vale of Lost Women.” We hope you’ll join in!

Howard: In the essay that concludes the book, “Hyborian Genesis,” Robert E. Howard scholar Patrice Louinet gives the probable background of this tale, recounting how Howard had grown more and more interested in tales of the American Southwest. Apparently at about the time he wrote this he’d begun to exchange tales with writer August Derleth, and recounted to him the story of the abduction of Cythia Ana Parker by the Commanche. Louinet speculates that this story was the inspiration behind “Vale.”

Last week I wrote that “Vale” was a rejected Conan story, but in actuality there’s no record that it was ever submitted. It might be that REH himself understood it wasn’t up to snuff and never bothered to turn it over for consideration.

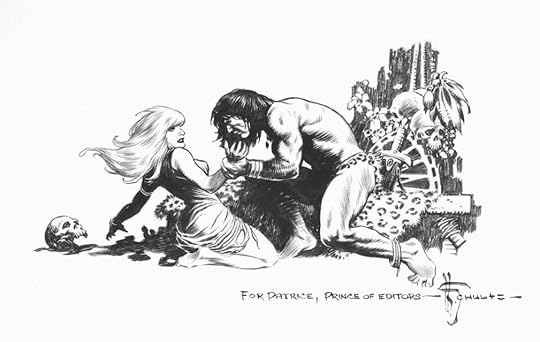

Conan & Livia by Mark Schultz

Bill: That would not surprise me.

Howard: It starts strongly enough, or at least, as strong as these lesser Conan tales that have dominated the last few we’ve read. Once again we see Conan through the eye of a woman from civilized lands. Louinet wrote that “As to the racial overtones of the story, while the violent ethnocentrism of the tale is understandable when we recognize its origin in the nineteenth-century Anglo-Saxon settler viewpoint, with the blacks standing in for Indians, it makes for unsettling reading for the modern audience.”

Indeed it does. Those references aren’t so onerous in the first section, and the story was promising enough that I lived in hope that I had mis-remembered my feelings. Conan at least is in fine form in the opening, and REH once again sets the stage and the situation before Conan strides into view. It’s understandable he might be motivated by a beautiful woman who looks more like someone from his background than those who surround him, but some of the white/black discussion is cringe inducing.

Robert E. Howard

Bill: It is indeed. This is most definitely not the story to hand to a Conan virgin, and it almost doesn’t even seem like the Conan we’ve grown to know in the last dozen stories.

Howard: Still, I could look past that and name those issues of the story simply as a product of its time if the rest of the tale were enjoyable, but it swiftly goes downhill after Livia’s discussion with Conan. In section III we witness Conan leading a brutal massacre of those hosting him and his warriors. And that might be expected of him, but I really don’t want to read about that. Following is the afterthought of a supernatural menace.

It’s just… tacked on. We don’t learn about the Vale of Lost Women until the section/chapter when Livia wanders off, and then she’s put into a sort of trance by the flowers and the brown women with glowing eyes as a bat-winged thing from cosmic gulfs that “lurk as thick as fleas outside the belt of light which surrounds this world” descends to transform or ravish or devour her. Fortunately Conan rides up and dispatches it in about two paragraphs. He’s more bothered by an ape than this thing of horror from beyond ken. He’s so jaded to horrors from beyond time that he mentally shrugs at them, which definitely weakens any feel of dread or tension.

Bill: I think “Vale” fails on most fronts, beyond providing interest for the REH enthusiast, and I almost think my favorite thing about it was Conan again using a beefbone to clean someone’s clock. There isn’t much said here about civilization and barbarism, beyond maybe the sentiment that some barbarians are worse than others and, of course, that Conan can find use for his talent for violence anywhere he goes. Structurally the whole story is kind of lopsided, and the second half, the actual Ovidian Vale of Lost Women, is disappointing: especially, as you say, in the nonchalant way Conan views the “rather common” Devil of the Outer Dark. I think the whole story really feels like REH running some ideas up the old flagpole to see how they work. Eventually those ideas, themes drawn from the American West, do work, just not here.

Bill: I think “Vale” fails on most fronts, beyond providing interest for the REH enthusiast, and I almost think my favorite thing about it was Conan again using a beefbone to clean someone’s clock. There isn’t much said here about civilization and barbarism, beyond maybe the sentiment that some barbarians are worse than others and, of course, that Conan can find use for his talent for violence anywhere he goes. Structurally the whole story is kind of lopsided, and the second half, the actual Ovidian Vale of Lost Women, is disappointing: especially, as you say, in the nonchalant way Conan views the “rather common” Devil of the Outer Dark. I think the whole story really feels like REH running some ideas up the old flagpole to see how they work. Eventually those ideas, themes drawn from the American West, do work, just not here.

Howard: I’ll turn a last time to Louinet’s analysis, which pretty much sums up my own impression. Howard might have been inspired by that tale from the American Southwest, but that inspiration was diluted “between the unconvincing supernatural threat and Livia’s penchant for nakedness.” If you have that comment in mind while you’re reading you can’t help but smile wryly. The word “naked” is used a lot to describe Livia, sometimes twice in the span of a couple of sentences, and she’s constantly disrobing or having clothes ripped from her. Maybe it should have been submitted to that lost pulp mag, Spicy Conan Stories.

Bill: I found the descriptions of her mounting hysteria more odious, very purple and over-the-top. It is a case in which having a female point of view character as foil to Conan backfired a bit on REH, who had been doing it so well in previous tales. Livia is the worst of these characters — oddly, she’s only one letter shy of Olivia, who is one of the best.

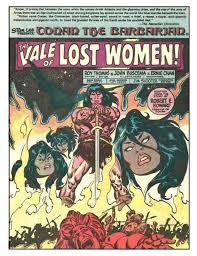

Howard: Interestingly enough, when it was adapted into a Conan comic during the original Roy Thomas Marvel run, it works fairly well, probably because some of the most egregious lines can be cut and the fight lengthened.

Howard: Interestingly enough, when it was adapted into a Conan comic during the original Roy Thomas Marvel run, it works fairly well, probably because some of the most egregious lines can be cut and the fight lengthened.

Bill: I can see how that would work; with a few tweaks you have an entertaining adventure. As it stands, though I think “The Vale of Lost Women” is of more worth for its reflection of REH’s evolving inspirations and methods than as an exciting chapter in Conan’s life.

Howard: I don’t think we’re alone in our opinions. Unlike all the other Conan stories we’ve revisited, even art was a challenge to find for this recap.

Next week we’ll take a look at “The Devil in Iron.” I have this one confused in my memory with “Iron Shadows in the Moon,” and it’s one I haven’t re-read before. I’m looking forward to seeing how it holds up.

October 28, 2015

Editing Harold Lamb

Bill Ward, Ryan Harvey, & Howard Andrew Jones, World Fantasy 2010.

In February of 2011 Bill Ward interviewed me for Black Gate magazine. Back then three things I’d been involved in were coming to life within a few months of each other — my first two novels (The Desert of Souls and Plague of Shadows) and the second wave of the Harold Lamb books I assembled for Bison Books/University of Nebraska Press.

You can find the other portions of the interview at Black Gate, but given that I’m often asked how I got involved in editing the Harold Lamb books, I thought it high time to move this portion of the interview to my own site.

I’d like to thank Bill for asking such great questions. I think it was only the year before that we’d finally met in person, at Dragoncon. In the picture here we’re standing with old friend Ryan Harvey, another brilliant essayist and writer. I have a slightly glazed look because I’ve been up late at the con for several days, and we all have red eyes because we’re vampires. Ryan’s holding an anthology that one of Bill’s stories had just been printed in, Desolate Places.

Anyway, all questions are from Bill. Take it away, old friend:

In part one of Black Gate’s interview with Howard Andrew Jones we heard about one of Howard’s new novels, The Desert of Souls, and the joys and pitfalls of writing fantasy stories set in an historical milieu. In our second installment we talk about Howard’s reverence for the greatly under-appreciated historical adventure writer Harold Lamb, and the massive project Howard undertook to collect and republish Lamb’s fiction to preserve it for new audiences.

All this talk about historical fiction naturally brings us around to Harold Lamb. When and where did you first encounter his work?

All this talk about historical fiction naturally brings us around to Harold Lamb. When and where did you first encounter his work?

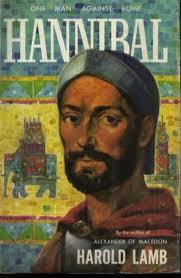

I first found him as a high school sophomore. I had to write a short history paper on a famous historical figure, and I happened to find Lamb’s biography of Hannibal on the library shelves. I loved that book. I had reread books in the past, but they were always novels or short story collections. Hannibal was the first non-fiction text I revisited again and again. Lamb presented what was almost a Shakespearean drama about a man blessed by the gods with brilliance and charisma, doomed never to achieve the one thing he truly fought for, which was the preservation of his homeland, the citystate of Carthage. A military genius, Hannibal won battles employing tactics that are still studied today, but no matter how clever he was he could not win the war. He had luck in abundance, but it was almost a curse, for while he continued to survive, all those closest to him fell. When he returned home to Carthage after the war he turned his intellect to reforming the state. He eliminated graft and corruption and overhauled the elective system so that senators, appointed to lifetime power, had to be elected every two years by the people. Though beloved by the commoners his sweeping changes drew only ire from the ruling elite, who lied to Rome, saying Hannibal was still plotting against them. He had to flee his city and wander for the rest of his life, taking employment with more and more distant places as a military adviser while the Romans expanded their holdings. Hunted to the end by Rome, he finally died by his own hand rather than permitting them to capture him alive.

It certainly wasn’t an uplifting tale, but it was a story about a man of integrity and honor who strove the whole of his life for what he believed in, and I deeply admired him for that, as well as his inspiring leadership and military brilliance. Those few surviving personal anecdotes about him revealed a dry, modern sense of humor. Lamb’s presentation of the information made a lifelong Hannibal fan of me (I don’t mention this in casual conversation anymore, as I have grown tired of having to say NOT Hannibal Lecter). I was old enough to understand part of the reason I loved the book was because of the writing, so I looked up other books by Harold Lamb and discovered the first collection of Khlit the Cossack stories. That was the most exciting fiction I’d read since Fritz Leiber’s tales of Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, and I recognized that I’d found a gifted author.

From fan to editor — how did you make the transition from admiring Lamb to actively working to preserve his legacy? The eight volumes of collected shorts from Bison Books must have been a great deal of work — did you realize what a huge undertaking it would be when you started?

From fan to editor — how did you make the transition from admiring Lamb to actively working to preserve his legacy? The eight volumes of collected shorts from Bison Books must have been a great deal of work — did you realize what a huge undertaking it would be when you started?

When I started I had no idea that there would even be an undertaking. I was just curious about all the stories he’d written that hadn’t ever been reprinted. There were a lot of them. One day while hunting used book search sites I saw two titles offered by the same seller. At that point I knew what all the names of Lamb’s published books were, yet these were unknown to me. I looked into the matter and discovered that these were some complete stories removed from pulp magazines and sewn into hardback covers by the late Dr. John Drury Clark for his personal reading. He had a box full of additional unreprinted Lamb stories, unbound, that Dr. Clark’s widow hadn’t put on the market because, she said, they were in pretty bad shape, though intact. I bought them, and as a result soon owned the bulk of Lamb’s uncollected fiction. It truly was like a treasure trove to me.

What a joy reading those stories proved to be; I savored every moment. I’ve talked elsewhere about the expectation that uncollected works are usually lesser stories — forgettable or early stuff — and how these grand novels, novellas, and short stories within defied that common wisdom. Unfortunately, they were all on dry, flaking pulp paper, and I decided that if I really wanted to preserve these, I’d best scan them, because some were disintegrating every time I turned a page. Those in the worst shape had letters and entire words dropping off from the margins.

That’s how it started. I bought a scanner and optical character recognition software and started preparing the manuscripts in worst shape first. What can I say? It took years, for the OCR process was time consuming, though far faster than typing the texts. I continued to track down other rare stories, assisted by family and friends in my search, and eventually found all of Lamb’s work for Adventure, where he did almost all of his best work. I got to exchanging notes with other Lamb fans, and we daydreamed about how great it would be to have these old texts between covers, and to have the serial stories collected in order, and by and by I started approaching publishers about reprinting the work. Because I’d been a professional editor for many years at that point, it wasn’t that intimidating to talk to another editor on the other end of the phone. What I didn’t know was that even though I’d already put in years and years of work that it would take years more! But the result was worth it, and a lot of good people helped me make it happen. Lamb’s work is too good to be forgotten, and it is my fondest wish that it not only stays in print, but that it will be rediscovered and enjoyed by a widening circle of readers.

It was most definitely worth it, and I share your hope that Lamb’s fiction will enjoy a justly-deserved renaissance. For anyone unfamiliar with Lamb’s extraordinary output, where would you recommend they start?

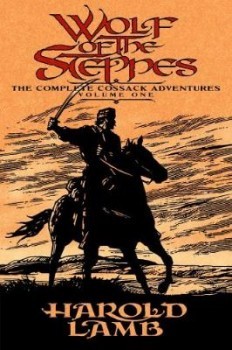

Readers who don’t know his work seem most responsive when they start with Swords from the West. It’s a fantastic collection of Crusader stories, showing the fall of kingdoms and the dooms of men, desperate battles and brave comrades, shrewd maids and scheming nobles. If you’re already a fan of the Conan stories and Fritz Leiber’s Lankhmar cycle, or love heroic fiction short stories in general, you might start with Wolf of the Steppes, the first of four books collecting the ongoing stories of Lamb’s Cossack adventurers. They’re from earlier in Lamb’s career, but Lamb was so accomplished that after the first short tales in Wolf, Lamb hit his stride and drafted some truly fantastic adventures, sending his character into lost cities, forbidden temples, and some of the most desolate and fascinating places on earth. I fell in love with his fiction because of these tales, and I love them still.

What would you say are the things you’ve learned from Lamb, as an author?

What would you say are the things you’ve learned from Lamb, as an author?

I’m still learning! I certainly try to emulate a command of the historical period I’m writing about, as he did, but I can’t help feeling that I’m building with smoke and mirrors while he was fashioning real structures. The man spoke at least a half dozen languages! I love how he never bothered taking you anywhere that wasn’t interesting to see, and the way he would place his characters in situations that required great cleverness to survive. I have to say that, much as I love rogues and “gray” characters like Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser, I also love the honor of Lamb’s heroes, most of whom would rather die than break their word or betray their convictions. I think those kind of protagonists have become unseasonably out of favor, and their outlooks mocked for being naïve or unrealistic, but I honestly wish that we saw more characters like them. Lamb was ahead of his time in understanding that good or evil didn’t reside only with people across the border, or folk with different religion. In Lamb’s writing, your most loyal friend might be someone who would have been a natural enemy. He wrote with, as John Miller said, “an honest multiculturalism.” Lamb’s women might not usually have been warriors, but they were vitally intelligent and shapers of events very different from female characters in the work of his contemporaries. I could go on and on about what’s great about Lamb. I guess you could say that I strive to follow his lead on all of these things. Most certainly I admire his skill at plotting. Things click together like puzzle pieces assembled by a master craftsman, but his plots aren’t usually predictable; events in the stories rise from the collision of motivations between characters. That’s certainly something I strive to achieve with my own fiction.

Next week brings the third and final installment of our interview, in which we talk about a variety of subjects including gaming and Howard’s newly released Pathfinder novel, Plague of Shadows.

__________

BILL WARD is a genre writer, editor, and blogger wanted across the Outer Colonies for crimes against the written word. His fiction has appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, as well as gaming supplements and websites. He is a Contributing Editor and reviewer for Black Gate Magazine, and 23rd in line for the throne of Lost Lemuria. Read more at BILL’s blog, DEEP DOWN GENRE HOUND.

October 26, 2015

Heroes of the Steppes: The Historicals of Harold Lamb

This article I wrote some years back has been floating around on the inter web in a couple of places, and I thought it past time for me to bring it back to my own site. So — here you go!

This article I wrote some years back has been floating around on the inter web in a couple of places, and I thought it past time for me to bring it back to my own site. So — here you go!

Before Stormbringer keened in Elric’s hand, before the Gray Mouser prowled Lankhmar’s foggy streets—before even Conan trod jeweled thrones under his sandaled feet, Khlit the Cossack rode the steppe. He isn’t the earliest serial adventure character, but his adventures are among the earliest that can still be read for sheer pleasure.

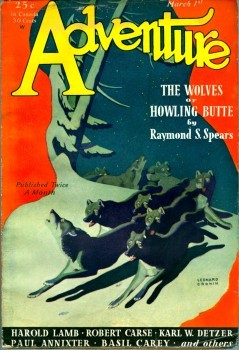

He was created in 1917 by Harold Lamb, in a time when “costume pieces” provided the same kinds of thrills that fantasy and science fiction adventure stories deliver today, and he appeared in the pulp magazines.

The best remembered of these magazines today are probably those devoted to the adventures of single characters—like Doc Savage or The Shadow—or the early magazines of the fantastic wherein those we now recognize as giants were published—Weird Tales, and, later, Unknown, Planet Stories, and other science fiction magazines.

Shortly after World War I, though, there was very little to be found in the realm of the fantastic. For all their fame, the later science fiction magazines and Weird Tales were hardly representative of the content found in most pulps. The most popular of magazines tended to be devoted to westerns and detective tales. Aside from the occasional Verne reprint and a few innovators—like the fellow who’d written of a civil war soldier transported to Mars—adventure was found in more recognizable places.

And then came Lamb.

About forty loosely linked novelettes in Adventure narrated the adventures of several Cossack heroes in the early seventeenth century… They are tales of wild adventure, full of swordplay, plots, treachery, startling surprises, mayhem, and massacre, laid in the most exotic setting that one can imagine and still stay in a known historical period on this planet.[1]

About forty loosely linked novelettes in Adventure narrated the adventures of several Cossack heroes in the early seventeenth century… They are tales of wild adventure, full of swordplay, plots, treachery, startling surprises, mayhem, and massacre, laid in the most exotic setting that one can imagine and still stay in a known historical period on this planet.[1]

Lamb’s fiction exploded with cinematic pacing. Expect slow spots when you’re reading even the best historicals from Lamb’s time, but don’t look for them in his work. It drove forward at breakneck pace, paused briefly to gather a breath, then plunged the reader back into suspense. It rang with the shouts of battle and the clang of swords. It swam in an atmosphere as heady and exotic to western eyes as Burroughs’ Mars. Consider this passage, composed in 1921. Khlit the Cossack is leading a small army of Tartars into battle against an army of the Mogul’s, many of whom ride massive war elephants, raining death from the howdahs perched upon the backs of the mighty beasts:

Khlit pointed to the howdah of the Northern Lord, glittering with its costly trimmings.

“Chagan, take a score of followers and slay me that chief.”

By now the arrows from the howdahs were flying among the Tatar riders, and their own arrows were deflected off the armored coverings of the beasts. Khlit rose to a standing position in his saddle and surveyed the masses of fighting men. He rode swiftly from clan to clan, bidding them draw away from the riverbank. In so doing they passed near the elephant of Paluwan Khan.

By now the arrows from the howdahs were flying among the Tatar riders, and their own arrows were deflected off the armored coverings of the beasts. Khlit rose to a standing position in his saddle and surveyed the masses of fighting men. He rode swiftly from clan to clan, bidding them draw away from the riverbank. In so doing they passed near the elephant of Paluwan Khan.

Chagan had driven his horse at the head of the giant beast, clearing a path for himself with his sword. He swung at the black trunk that swayed above him, missed his stroke, and went down as his horse fell with an arrow in its throat.

“Bid your elephant kneel, cowardly lord,” he bellowed, springing to his feet and avoiding the impact of the great tusks, “and fight as a man should!”

His companions being for the most part slain, Chagan seized a fresh mount that went by riderless and rode against the elephant’s side. Gripping the canopy that overhung the elephant’s back, with teeth and clutching fingers he drew himself up, heedless of blows delivered upon his steel headpiece and mailed chest.

“Ho!” he cried from between set teeth. “I will come to you, Northern Lord!”

“Ho!” he cried from between set teeth. “I will come to you, Northern Lord!”

An arrow seared his cheek and a knife in the hand of an archer bit into the muscles of a massive arm. Chagan’s free hand seized the mahout and jerked him from behind the ears of the elephant as ripe fruit is plucked from a tree. At this the beast swayed and shivered, and for an instant the occupants of the howdah were flung back upon themselves and Chagan was nearly cast to earth.

Kneeling, holding on the howdah edge with a bleeding hand, he smote twice with his heavy sword, smashing the skull of an archer and knocking another to the ground. The remaining native thrust his shield before Paluwan Khan.

But the Northern Lord, no coward, pushed his servant aside and sprang at Chagan, scimitar in hand.

The Tatar sword-bearer, kneeling, wounded, was at a disadvantage. Swiftly he let fall his own weapon and closed with Paluwan Khan, taking the latter’s stroke upon his shoulder. A clutching hand gripped the throat of the Northern Lord above the mail and Chagan roared in triumph.

Pulling his foe free of the howdah, the Tatar lifted Paluwan Khan to his shoulder and leaped from the back of the elephant.

Pulling his foe free of the howdah, the Tatar lifted Paluwan Khan to his shoulder and leaped from the back of the elephant.

The two mailed bodies struck the earth heavily, Paluwan Khan underneath; and it was a long moment before Chagan rose, reeling. In his bleeding hand he clasped the head of the Northern Lord. And, reeling, he made his way to Khlit, through the watchers who had halted to view the struggle upon the elephant.

“Kha Khan, look upon your foe!”

And Chagan tossed the head aside, to run, staggering, at Khlit’s stirrup as the Tatars swept athwart the Mogul’s line, away from the river.[2]

Prior to creating Khlit, Lamb had worked steadily in the pulps for a number of years, cracking the prestigious Argosy and a number of other magazines. His early stories are sometimes entertaining but rarely remarkable. Anyone familiar only with these pieces, set at the time of their composition, probably wonders what all the fuss is about.

The fuss began shortly after Lamb broke into Adventure, later christened the “dean of pulp magazines” by Newsweek. It was, as Bob Weinberg has written, “the very best the pulps had to offer.”[3]

The fuss began shortly after Lamb broke into Adventure, later christened the “dean of pulp magazines” by Newsweek. It was, as Bob Weinberg has written, “the very best the pulps had to offer.”[3]

Arthur Sullivant Hoffman, Adventure’s editor, gave Lamb leave to write about what he liked best, and what Lamb liked best were stories set in the East. He had discovered histories of Asia while in the libraries of Columbia, prior to the war, and described them as “gorgeous and new.” Born with what he later described as damaged eyes, ears and speech—though he wrote that those defects had mostly righted themselves by the time he was an adult–Lamb alternated his time growing up between his grandfather’s library and the outdoors. Hoffman described him as a compulsive scholar, but Lamb seemed to prefer studying those subjects which interested him rather than those required for school, for he nearly flunked out of Columbia, where he was to be found on the tennis court when he was not in the book stacks.

Lamb’s writing hit its stride when he drafted a tale set in a Cossack camp in the 16thcentury. “Khlit” is short and relatively slight compared to what came after, but there is potential in the work; reading it is like glimpsing the embers in a fireplace as they begin to glow red. No longer writing of the West and familiar settings, Lamb shed conventions and stereotypes and dove headlong into storytelling. He wrote a longer sequel to “Khlit” and the potential glimpsed in the first story brightened into flame. This tale was followed by another, at which point Lamb’s creation blazed like a roaring bonfire.

Lamb had found a setting that allowed him to write to his strengths and minimize his weaknesses. He had immersed himself in the times and places and brought them vividly to life, though he never bogged the reader down with detail. David Drake touches on this in an introduction to Volume 2 of Lamb’s Cossack stories, Warriors of the Steppes: “The author keeps the real historical background a shadowy presence enveloping his stories instead of trotting it out to prove his erudition; but the more a reader knows of that background, the more certain he becomes that Lamb had all the details at his fingertips.”

Lamb had found a setting that allowed him to write to his strengths and minimize his weaknesses. He had immersed himself in the times and places and brought them vividly to life, though he never bogged the reader down with detail. David Drake touches on this in an introduction to Volume 2 of Lamb’s Cossack stories, Warriors of the Steppes: “The author keeps the real historical background a shadowy presence enveloping his stories instead of trotting it out to prove his erudition; but the more a reader knows of that background, the more certain he becomes that Lamb had all the details at his fingertips.”

Lamb placed his emphasis on conveying the story rather than conveying his scholarship, and he made each tale unique. In adventure fiction we are used to and often make excuses for the fact that certain elements appear and re-appear time and again. We may even see the same plot redressed by the same author–as Edgar Rice Burroughs so often did with his tales of Tarzan or John Carter–or have a good sense of how it will all turn out after the first few pages. Not so with Lamb. Even a jaded reader, even one familiar with Lamb’s work, is unlikely to anticipate the turns his plots will take. His characters do not remain static–they change, they age, and some of them die.

The Cossack frontier and the steppe were an inspired choice for an adventure series, and the 16th century the perfect period for it. Empires were dying and a-borning, and in that chaos a single man could make his own destiny, carving it out of the wreck with a saber. Christian and Muslim, Buddhist and shamanist, hunter and herder and farmer and city-man met and connived and struggled over half a world.[4]

Harold Lamb sent Khlit adventuring into the dangerous, shifting border between Russia and lands to the east and south. His hero was a Cossack, one of that breed who lived in picked war camps along the frontier–self appointed protectors who had all the independence and skilled horsemanship of an American cowboy, the camaraderie of The Three Musketeers, and a reputation a little like a cross between the famed French Foreign Legion and pirates. Tricksters, daredevils, vagabonds, the Cossacks lived a dangerous and exciting existence. “For weapons, the free Cossacks were forced to rely on what they could take from the Moslems, who were the best armed troops in Europe at that time. No one received any pay… Only two conditions were made to a newcomer; he must be able to use weapons, ride and take care of himself, and he must be a believer in God and Christ. Every new arrival was expected to perform some feat to show his worth. A good many died in attempting to shoot the cataracts of the Dneiper, or in jumping their horses over the palisade around the camp.”[5]

Harold Lamb sent Khlit adventuring into the dangerous, shifting border between Russia and lands to the east and south. His hero was a Cossack, one of that breed who lived in picked war camps along the frontier–self appointed protectors who had all the independence and skilled horsemanship of an American cowboy, the camaraderie of The Three Musketeers, and a reputation a little like a cross between the famed French Foreign Legion and pirates. Tricksters, daredevils, vagabonds, the Cossacks lived a dangerous and exciting existence. “For weapons, the free Cossacks were forced to rely on what they could take from the Moslems, who were the best armed troops in Europe at that time. No one received any pay… Only two conditions were made to a newcomer; he must be able to use weapons, ride and take care of himself, and he must be a believer in God and Christ. Every new arrival was expected to perform some feat to show his worth. A good many died in attempting to shoot the cataracts of the Dneiper, or in jumping their horses over the palisade around the camp.”[5]

Khlit, also known as the Wolf, is owner of a curious sword which has earned him the additional sobriquet of Khlit of the curved saber. Contrary to current trends in popular fiction, where the hero is a stripling coming into his own (a la Luke Skywalker, Frodo Baggins, or uncounted numbers of stable boys destined to be kings), or a grown man seasoned with experience but still in the prime of life (Indiana Jones, James Bond), Khlit is an older man from his first adventure. He is one of a very few Cossacks who has survived into his middle-years. This is no accident, and while we soon see that Khlit is a fine horseman and sword wielder, it is his keen intellect which sees him through so many escapades. Archetypally he is not Achilles, Luke Skywalker, or Superman–he is modeled from wily Odysseus.

Lamb didn’t leave Khlit in the Cossack camp for long. When enemies try to force Khlit into “retirement” (meaning into a monastery) at the opening of the third tale, Khlit will have none of it, and gallops off into the wilds of Asia, China, and India. It’s a glorious ride. With him we infiltrate the hidden fortress of assassins, Alamut, track down the tomb of Genghis Khan, flee the vengeance of a dead emperor, lead the Mongol horde against impossible odds, safeguard a stunning Mogul queen through the lands of her enemies, stamp out a cult of stranglers, and much more. His nineteen tales, some of them short novels, are adventure writing at its very finest, awash with ancient tombs, gleaming treasure, and thrilling landscapes. Khlit matches wits with deadly swordsmen, scheming priests, and evil cults; he rescues lovely damsels, rides with bold comrades, and hazards everything on his brains, skill, and luck.

Lamb didn’t leave Khlit in the Cossack camp for long. When enemies try to force Khlit into “retirement” (meaning into a monastery) at the opening of the third tale, Khlit will have none of it, and gallops off into the wilds of Asia, China, and India. It’s a glorious ride. With him we infiltrate the hidden fortress of assassins, Alamut, track down the tomb of Genghis Khan, flee the vengeance of a dead emperor, lead the Mongol horde against impossible odds, safeguard a stunning Mogul queen through the lands of her enemies, stamp out a cult of stranglers, and much more. His nineteen tales, some of them short novels, are adventure writing at its very finest, awash with ancient tombs, gleaming treasure, and thrilling landscapes. Khlit matches wits with deadly swordsmen, scheming priests, and evil cults; he rescues lovely damsels, rides with bold comrades, and hazards everything on his brains, skill, and luck.

Gruff and taciturn, Khlit is a firm believer in justice. He is the friend and protector of many women, but he leaves romance to his sidekicks and allies. He rides alongside heroes from many different nationalities, with varied beliefs-—among them a heroic Afghan swordsman, a Manchu Archer, a Hindu warrior, and daring Mongol horsemen. And not all of his allies are men:

Weakly Chepé Buga staggered out into the hall. His companion closed the door behind him. Then the khan sank down beside Atagon. For the first time he saw his companion by the firelight. Even to his dimmed eyes the figure did not seem like Chagan’s bulk. The firelight gleamed on the small shield of Atagon which the other carried.

Weakly Chepé Buga staggered out into the hall. His companion closed the door behind him. Then the khan sank down beside Atagon. For the first time he saw his companion by the firelight. Even to his dimmed eyes the figure did not seem like Chagan’s bulk. The firelight gleamed on the small shield of Atagon which the other carried.

Above the shield was a white, anxious face and a tangle of gold hair.

“ Chinsi!” he gasped. “ How–”

“ Chagan could not leave the tower,” she said softly, “they are hard beset. I took Atagon’s sword and shield, to help you if I could.” The girl laid down her shield and knelt beside him.

“ They have gone from the door,” she said eagerly, “I heard them.”

Her glance fell on the dark stain that covered the khan’s mail, and she gave a cry of dismay.

Chepé Buga shook his head in mute protest as she tried to draw off his heavy mail.

“The spear,” he whispered, “went deep. Your sword killed the man that did it. Brave Chinsi, the golden-haired!“

Chepé Buga’s dark head sank back on the floor, and his sword fell from his fingers. The watching girl saw a gray hue steal into his stern face. Chepé Buga, she knew, was dying.

Chepé Buga’s dark head sank back on the floor, and his sword fell from his fingers. The watching girl saw a gray hue steal into his stern face. Chepé Buga, she knew, was dying.

“Harken,“ she whispered, pointing to Atagon who lay beside them, conscious. “Let the presbyter bless you, Chepé Buga. The priest will save your soul, for heaven.”

The Tatar moved his head weakly until he could see Atagon. Something like a smile touched his drawn lips. The girl bent her head close to his to hear what he was trying to say.

“Nay, Chinsi. Do you bless me. Heaven is—-where you are.”

Raising one hand, Chepé Buga caught a strand of the girl‘s hair which lay across his face. The girl, who had stretched out her hand to Atagon, sighed regretfully. Yet she did not move her head away.

Chepé Buga’s hand was still fast in her hair. But its weight hung upon the strand, and the Tatar’s eyes were closed when Khlit and Chagan ran from the tower stairs into the hall a moment later.[6]

Over the course of his journeys Khlit may bear some of his own prejudices with him, but his perceptions grow and change: the Cossack first views Tatars as hereditary enemies, then embraces their culture as his own. And then there is the devoted friendship shared between Khlit and Abdul Dost, who teams up with the Cossack in four stories of the saga; an Eastern Orthodox Christian and a Muslim. Both are devout in faiths that have lost little love for one another, yet the men are brothers of the sword. Lamb has no theological or philosophical axe to grind–he aims only to present a cracking good story, and he almost always succeeds.

Over the course of his journeys Khlit may bear some of his own prejudices with him, but his perceptions grow and change: the Cossack first views Tatars as hereditary enemies, then embraces their culture as his own. And then there is the devoted friendship shared between Khlit and Abdul Dost, who teams up with the Cossack in four stories of the saga; an Eastern Orthodox Christian and a Muslim. Both are devout in faiths that have lost little love for one another, yet the men are brothers of the sword. Lamb has no theological or philosophical axe to grind–he aims only to present a cracking good story, and he almost always succeeds.

Lamb never wrote overtly of the fantastic or the supernatural like Robert E. Howard, keeping his historical fiction grounded in reality, but he did play around its edges, frequently exposing his characters to the strange and macabre. Some of his villains masquerade as sorcerors and miracle workers of great power. Here Khlit and his Tatar friend Chagan follow a ghostly noise arising from ruins near a desert mound in “Roof of the World:

The hair had not descended to its normal position on the back of Chagan’s head when Khlit joined him. The Cossack had heard the voice. The two men gazed at the mound curiously.

“Said I not the place was rife with evil spirits?” growled the sword-bearer. “That is the song I heard in the night.”

“Said I not the place was rife with evil spirits?” growled the sword-bearer. “That is the song I heard in the night.”

The voice dwindled and was silent. Khlit inspected the stone ruins which showed through the sand. Then he motioned to Chagan.

“Here is no sand dune,” he growled. “The sand has covered up a building, and one of size. Some parts of the walls show through the sand. If we look we will find a woman in the ruins.”

“Nay, then she must eat rock and drink from the Jallat Kum[7],” protested the Tatar. “If there was a house here, even a palace, the sand has filled it up–”

Nevertheless he followed Khlit as the Cossack climbed over the debris of rock that littered the sides of the mound. They went as far as they could, stopping at the edge of the basin which the mound adjoined. There was no sign of a person among the remnants of walls. But Khlit pointed to the tower on the summit of the mound.

Chagan objected that there were no footsteps to be seen leading to the ruined tower. Khlit, however, solved this difficulty by scrambling up the slope. The shifting sand, dislodged by his progress, fell into place again behind him, erasing all mark of his footsteps. He vanished into the pile of masonry. Presently he reappeared and directed Chagan to bind together a torch of dead tamarisk branches and to light it at their fire.

When the sword-bearer had done this, Khlit assisted him to the summit of the hillock. There he pointed to the stone tower. Its walls had crumbled into piles of stones, projecting from the sand no more than the height of a man, but in the center of the walls a black opening led downward.[8]

When the sword-bearer had done this, Khlit assisted him to the summit of the hillock. There he pointed to the stone tower. Its walls had crumbled into piles of stones, projecting from the sand no more than the height of a man, but in the center of the walls a black opening led downward.[8]

A private man, details about Lamb’s home life are scarce. He married Ruth Barbour in 1917, and by all accounts their marriage was a long and happy one. They had two children, Frederick and Cary. He served in both world wars–as an infantry man in World War I (though he saw no action) and as an O.S.S. operative overseas in World War II. Lamb knew many languages: by his own account, French, Latin, ancient Persian, some Arabic, a smattering of Turkish, and a bit of Manchu-Tartar and medieval Ukranian. He traveled throughout Asia, visiting most of the places he wrote about.

As the pulp magazine market dried up, Lamb moved on to write well regarded histories and biographies, and co-wrote numerous screenplays for Cecil B. Demille. Because of his expertise in the Middle-East, he was sometimes consulted by the stated department. His pulp work was mostly forgotten until the very end of his life, when Lamb was asked to select a handful of Cossack stories for reprint by Doubleday. He did not live to see the collection printed, and most of his adventure stories have languished in obscurity until 2006, when they were collected in trade paperback by the University of Nebraska Press’s Bison Books imprint.

The volumes feature appendices with never-before-reprinted letters from Lamb about his stories, introductions from fantasy and science fiction luminaries like David Drake, S.M. Stirling, and E.E. Knight, and a gorgeous interior map detailing Khlit’s travels.

The Cossack stories have never been available in a complete set, in order, and some have never seen print since their Adventure days. It is my sincere hope that they will now, at last, be discovered and celebrated and enjoyed by legions of heroic fiction fans familiar with authors and works that might never have existed without Lamb to lead the way.

[1] de Camp, L. Sprague. Marching Sands. “Harold Lamb.” New York: Hyperion, 1974.

[2] Lamb, Harold. “The Curved Sword.” Adventure. November 1, 1920.

[3] In his introduction to Swords from the West.

[4] Stirling, S.M. “Introduction.” Wolf of the Steppes. Bison Books, 2006.

[5] Lamb, Harold. Letter to Adventure, published in 10/20/1923 “The Camp-Fire” letter column.

[6] Lamb, Harold. “Changa Nor.” Adventure. Feb. 1, 1919.

[7] Quicksand.

[8] Lamb, Harold. “Roof of the World.” Adventure. April 15, 1919.

October 23, 2015

The Coming of Conan Re-Read: “Rogues in the House”

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “Rogues in the House.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill Ward and I are reading our way through the Del Rey Robert E. Howard collection The Coming of Conan. This week we’re discussing “Rogues in the House.” We hope you’ll join in!

Bill: “Rogues in the House” is a welcome return to form after a few lesser Conan stories, and once again it sees Conan run afoul of civilization’s ways. The story reprises elements of “The God in the Bowl” and “The Tower of the Elephant” to give us Conan as a rogue and outlander — indeed the story begins with his incarceration for the murder of a priest. The priest in question was a thoroughly corrupt fence of stolen goods and police informer and, like the Red Priest at the center of this story or Kallian Publico or Yara from the aforementioned yarns, a prime example of the height of civilized hypocrisy and self-interest. A distrustful Conan says later in the story “When did a priest keep an oath?” and is proven correct in his distrust. The priestly class seems singled out as a prime exemplar of REH’s critique of civilized ways.

That conflict between barbarian and civilized man has been only a minor note in the last few stories, but in “Rogues in the House” it seems to inform everything. The story begins with the introduction of the Red Priest and the nobleman Murilo, the man that would get Conan into this adventure, in a very civilized, affected atmosphere. The threat made against Murilo is silent, unspoken, almost polite — its brutal image of a severed ear is housed, almost softened, by the decadent trappings of a golden box. Murilo, like his predecessor in “The God in the Bowl,” realizes he needs a stranger to dare the house of his priestly rival but, unlike in that earlier story, Murilo proves himself to be an honorable man, despite also qualifying as one of the “Rogues in the House” of the title.

Howard: Honorable in his personal dealings at least, but a traitor to his country! The story is so economical we never learn the reasons for Murilo’s selling state secrets, but we do see his personal bravery even in the face of danger, and he holds off trying to attack Thak — until he has a clear shot –for fear of hitting Conan. He’s a man of his word, so one wonders how he ends up as a traitor. It’s not really important to the tale, though. It’s a point of character complexity.

Howard: Honorable in his personal dealings at least, but a traitor to his country! The story is so economical we never learn the reasons for Murilo’s selling state secrets, but we do see his personal bravery even in the face of danger, and he holds off trying to attack Thak — until he has a clear shot –for fear of hitting Conan. He’s a man of his word, so one wonders how he ends up as a traitor. It’s not really important to the tale, though. It’s a point of character complexity.

Bill: We learn this early in the story, after Murilo’s plan to free Conan from prison goes awry, he himself goes to do the task he hired Conan to do — kill Nabonides, the Red Priest. That alone elevates him well above the schemer that betrayed Conan in “The God in the Bowl” and, once the Cimmerian joins him in the pits below the Red Priest’s abode, the two work well and honestly together to resolve the chaos storming around the Red Priest and his escaped creature, Thak the man-ape. Murilo might have perfumed locks (by which Conan’s heightened senses recognize him in the dark), but he’s also got courage and decency, two traits in short supply in REH’s civilized characters.

Howard: Very true. We can’t imagine Conan swooning at sight of the ape man, but Murilo does. We can’t imagine Murilo trying to jump on Thak’s back and wrestling him. Yet he’s brave and resourceful and honorable at a personal level. He is, in short, a decent civilized man, which allows a different juxtaposition from that we usually see between Conan and cultured people.

Howard: Very true. We can’t imagine Conan swooning at sight of the ape man, but Murilo does. We can’t imagine Murilo trying to jump on Thak’s back and wrestling him. Yet he’s brave and resourceful and honorable at a personal level. He is, in short, a decent civilized man, which allows a different juxtaposition from that we usually see between Conan and cultured people.

Bill: The Red Priest himself is one of the eponymous “rogues” of the title, a man described by Murilo as a plunderer and exploiter who sacrifices the future of his people for his own naked ambition. Indeed, Murilo cites Conan as the most honest rogue of them all, because he does what he does openly, even if it is theft and murder. Murilo and Conan are there to kill the Red Priest (and they aren’t the only ones!), but the three briefly join forces to survive the greater danger of the amok man-ape. In the end, of course, the treacherous priest betrays Conan and Murilo, though he adheres to the letter of their agreement and gleefully boasts of the technicality that allows him to keep his word — an oath made by a priest to the highest Hyborian god no less — just like you’d expect from a parasite of civilization.

The Red Priest is a manipulator, but he’s no magician like Yara. I thought it said interesting things about his character that he is a master of technology, that most civilized of things — his house is rigged with traps and he has a clever surveillance system that utilizes mirrors. Conan dismisses it all as witchery, but it is of course the opposite — what seems supernatural about the priest is really just more manipulation. This control extends even to living things, from the King of the city to lowly Thak, enslaved and abused man-ape of the far east.

Howard: And it’s strange that Murilo trusts him, but I suppose that points again to Murilo’s innate decency. And folly. He, unlike Conan, can’t really stand on his own. He doesn’t have the sense to trust his instincts. He’s right when he says Nabonides would never betray the oath he swore, but doesn’t reckon that the Red Priest will find another way to achieve his aim. Conan, more versed now to the kind of trickery that civilized man practices than he was in “The Tower of the Elephant,” doesn’t trust Nabonides no matter what he promises. He may not understand civilization, but he understands men and their behavior.

Howard: And it’s strange that Murilo trusts him, but I suppose that points again to Murilo’s innate decency. And folly. He, unlike Conan, can’t really stand on his own. He doesn’t have the sense to trust his instincts. He’s right when he says Nabonides would never betray the oath he swore, but doesn’t reckon that the Red Priest will find another way to achieve his aim. Conan, more versed now to the kind of trickery that civilized man practices than he was in “The Tower of the Elephant,” doesn’t trust Nabonides no matter what he promises. He may not understand civilization, but he understands men and their behavior.

Bill: If the Red Priest represents civilization at its worst, Thak is savagery at its most dangerous. It is no accident that the massive man-ape clads himself in the red mantle of his master. Certainly it allows for a brief moment of confusion as to what sort of were-sorceries the Red Priest gets up to, but much more to the point it shows a powerful innocent wholly corrupted by the civilization around him. Thak does nothing that his master has not already done, his simple imitative behavior is bloodthirsty, but it is learned. It is the Red Priest that has raised Thak to be a monster — a monster in his own image.

Howard: That’s a really good point, and one that isn’t stated explicitly in the plot. There’s more going on in these stories than is apparent from a simple surface reading, although it’s quite possible to just enjoy Conan tales as grand adventures.

Howard: That’s a really good point, and one that isn’t stated explicitly in the plot. There’s more going on in these stories than is apparent from a simple surface reading, although it’s quite possible to just enjoy Conan tales as grand adventures.

On re-reading it I was surprised that I haven’t visited this one more often. It gallops along. A lot happens in a short time because it’s told with such economy. And it’s very different from what has come before. I’ve been reading a lot of Conan pastiche in my downtime via The Savage Sword of Conan reprints recently, and so many of those writers model a Conan story off of the formula we saw in the last stories — monster, half-naked damsel, evil wizard/trap, escape. “Rogues in the House” breaks the formula and for this reason is even more of a pleasure.

Stepping back you can see how it’s a strange beast inspired from multiple sources — weird death traps out of Fu Manchu stories, a system of mirrors set to emulate a modern mastermind’s hidden cameras, and an ape servant who’s rebelled against his master. If someone had come and babbled the various story elements to me I would have rolled my eyes. Yet it works very well, in part because once it starts rolling it just never lets up.

You could say that about stories that catch you up and then realize upon re-examination that some of the elements didn’t make sense. That, however, can’t be said about “Rogues.” In retrospect it’s one fine scene after another, although my favorite moment may well be the conclusion.

Bill: In the end Thak has an honorable death at the hands of a fellow outsider, and Conan honors his opponent by confirming that he was indeed a man, and a mighty one, and Conan’s victory over him is worthy of song. The Red Priest, on the other hand, gets his head bashed in by a thrown stool in mid-sentence. The contrast couldn’t be more clear, nor the meaning more eloquently expressed. One wonders if Conan himself couldn’t have turned out to be something like Thak had his life gone another way, or if his spirit had proven less indomitable.

Bill: In the end Thak has an honorable death at the hands of a fellow outsider, and Conan honors his opponent by confirming that he was indeed a man, and a mighty one, and Conan’s victory over him is worthy of song. The Red Priest, on the other hand, gets his head bashed in by a thrown stool in mid-sentence. The contrast couldn’t be more clear, nor the meaning more eloquently expressed. One wonders if Conan himself couldn’t have turned out to be something like Thak had his life gone another way, or if his spirit had proven less indomitable.

Howard: “His blood was red after all.” I love that. Anyone who thinks Conan has no sense of humor needs to take another look at these stories. He aims the traitorous woman for the cesspool to take his revenge, then laughs, and there’s this quip here… although Conan might simply have been making an observation. I’m inclined toward the former though, because Conan’s not so dense to believe that the red priest’s blood might be a different color, not based on the word of some rumor.

Bill: “Rogues in the House” does what the best Conan stories do, weaving character and theme together with strands of fierce adventure and sense of wonder, and I happily list it among my favorites.

Howard: I now list it among my favorites as well, and scratch my head a little that it wasn’t already there. Next week: “The Vale of Lost Women.” I’m not sure that Conan story’s a favorite of any fan. It’s one of the rejected Conan stories, found among Robert E. Howard’s papers long after his death.

October 21, 2015

Swinging Along

I’m still swinging through a number of sites on my tour promoting the new novel. Over the last few days I’ve appeared at two sites, answering some of the most detailed questions I’ve yet been asked over the course of the tour.

I’m still swinging through a number of sites on my tour promoting the new novel. Over the last few days I’ve appeared at two sites, answering some of the most detailed questions I’ve yet been asked over the course of the tour.

Over at My Bookish Ways I talked about a whole range of topics, including how I researched the novel and what I’m currently reading (or looking forward to reading) who my all-time favorite writers are. My laudatory comments about Leigh Brackett were cut for space, but regular site visitors can find my musings on her in other spots on the web, and even in a prior blog tour post.

GeekDad’s Ryan Hiller is a diver and asked a lot of great questions about how I approached the underwater scenes in the book. He also took a pretty thorough look at this web site prior to the interview so he could ask questions based on what he found. For instance, he got me to talk a little bit more about some of my writing techniques and my favorite role-playing games, even a little about some of my favorite characters. That interview is here.

GeekDad’s Ryan Hiller is a diver and asked a lot of great questions about how I approached the underwater scenes in the book. He also took a pretty thorough look at this web site prior to the interview so he could ask questions based on what he found. For instance, he got me to talk a little bit more about some of my writing techniques and my favorite role-playing games, even a little about some of my favorite characters. That interview is here.

So, have you bought your copy yet?

Howard Andrew Jones's Blog

- Howard Andrew Jones's profile

- 368 followers