A.C.E. Bauer's Blog, page 9

January 3, 2012

Star Wars, flying snowmen, and suspension of disbelief

I grew up during the Apollo space missions. I can remember clearly the day Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped on the moon. The event riveted our attention—and all matters of space flight became fascinating. As I followed one amazing trip after another, one of the many cool things I learned was that sound does not carry in the void of space.

I grew up during the Apollo space missions. I can remember clearly the day Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped on the moon. The event riveted our attention—and all matters of space flight became fascinating. As I followed one amazing trip after another, one of the many cool things I learned was that sound does not carry in the void of space.Fast forward to 1977. I went to see Star Wars with anticipation. The characters, the plot, the setting, the many creatures somehow both strange yet familiar, engaged me. But as the story took us into space, each and every ship could be heard in the void. Explosions were loud. And I spent the whole time screaming (in my head), “There’s no sound in space!”

Don’t get me wrong. I liked the movie well enough to see the two sequels—but the sounds in space continued to bother me. It threw me out of the story each and every time.

John Scalzi calls this a flying snowman moment

—named after a moment when his spouse was thrown from a children’s book’s story when a snowman flew. It’s the moment when you tell yourself, “I’ll buy into the world of this story, but this here just doesn’t make sense.”

John Scalzi calls this a flying snowman moment

—named after a moment when his spouse was thrown from a children’s book’s story when a snowman flew. It’s the moment when you tell yourself, “I’ll buy into the world of this story, but this here just doesn’t make sense.”The thing about flying snowmen moments is that they are as varied as people—a flying snowman might bother one person, me it’s seeing a snowman eat soup (which, in the book, he does sometime before he flies). Whatever the trigger, the reader (or watcher or listener) is no longer in the story.

My role as a writer is to try and prevent flying snowmen moments from occurring in my stories. After all, I create worlds where fairy godmothers are real, where crows are friends of fairies, where an immortal man lives in the Quebec Laurentians. And so I develop characters, settings and plot, as convincingly as I can, so that readers won’t see the leap into the new and strange that I present. I lead them into a suspension of disbelief, and I do my best to keep them there by making my worlds whole and consistent.

Yet something may jar a reader. Even if, before publication, my story is read by trusted readers, editors and copy editors who make it their jobs to find those flying snowmen, no one can catch every trigger of disbelief. My goal has to be to get readers to roll with it.

Think of the recent Muppets movie. From the get-go, the audience knows that the Muppets’ world is impossible, yet we roll with each and every absurdity because the movie revels in them. It’s the point of the show. And we agree to suspend disbelief not because the Muppets’ world becomes any more believable as the movie progresses, but because we are invested in a cast of characters whose actions and roles we love.

Think of the recent Muppets movie. From the get-go, the audience knows that the Muppets’ world is impossible, yet we roll with each and every absurdity because the movie revels in them. It’s the point of the show. And we agree to suspend disbelief not because the Muppets’ world becomes any more believable as the movie progresses, but because we are invested in a cast of characters whose actions and roles we love.It’s why I watch Star Trek even while the Enterprise hums in space. Or why we believe Wily Coyote isn’t dead despite explosions, being crushed by anvils, and repeated falls from deadly heights. Or why we agree to let Harry Potter survive (or revive) even when he shouldn’t.

We want a riveting story to reach a satisfying conclusion. And so an audience will suspend disbelief, even through flying snowmen moments, if the plot, setting and characters carry us through. No small task.

Published on January 03, 2012 09:31

December 31, 2011

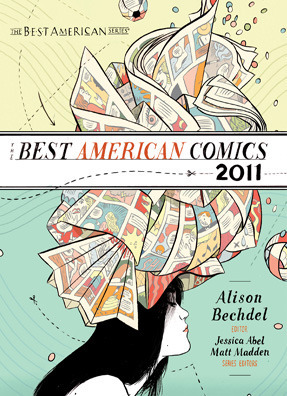

The Best American Comics 2011

The cover got me. I spent as much time admiring Jillian Tamaki’s illustrations of people wearing gorgeous hats made from comics pages as I did any of the pieces in The Best American Comics 2011. And the pieces are a revelation.

The cover got me. I spent as much time admiring Jillian Tamaki’s illustrations of people wearing gorgeous hats made from comics pages as I did any of the pieces in The Best American Comics 2011. And the pieces are a revelation.The title of the anthology is misleading. It’s not the best comics of 2011 (where’s Marzi?): the entries are chosen from graphic novels, pamphlet comics, newspapers, magazines, mini-comics and webcomics published between September 1, 2009 and August 31, 2010. But never mind. The book provides a window into what Alison Bechdel (of Fun Home and Dykes to Watch Out For fame) views as the best comics for that period, as sent to her by the series editors, Jessica Abel and Matt Madden. Her choices are idiosyncratic but are truly the best—from her point of view.

A word of warning for those not familiar with the format: despite the fact that these are called comics, they aren’t the funny pages. The stories are about adult matters for an adult audience. And Bechdel’s selections do lean towards the darker side.

The subject matter can be dark enough to make some stories hard to read—Joe Sacco covers a massacre of Palestinian men in 1956; Chris Ware follows the consequences of a parent physically abusing his child; Jaime Hernandez describes repeated sexual abuse between children; Julia Gfrörer portrays a man in love with a dead woman who wants to be killed by a witch. The art, too, can be unsettling—in Michael DeForge’s fantastic world an imaginary beast gives up its teeth and skin to transform a creature into a parody of a pin-up girl.

But there is plenty of humor as well. Kevin Mutch explores the meaning of quantum mechanics in a bar/diner filled with zombies. Joey Alison Sayers follows the misadventures of a syndicated comic strip over time. Kate Beaton tells you probably everything you want to know about the Great Gatsby—if you paid attention. David Sayers gives the funniest rendition of comics tropes in six succinct panels.

And in between the tough subjects and hilarity, there are love stories, psychedelic wonders, art and feminism, science fiction, history, fantasy, memoirs, all the oddities that come when writers and artists explore the human condition.

No one will like all the selections. That’s only to be expected. (I was less than fond of Dash Shaw’s off-kilter world.) But the overall effect of the compilation is to give a sense of the richness of the comics realm. As Alison Bechdel explains in her introduction:

Most of these cartoonists are looking just a little beyond the horizon. It doesn’t take anything away from comics to recognize that some of what you read here is also great literature.

Indeed.

Published on December 31, 2011 10:22

December 21, 2011

It only takes a girl

Published on December 21, 2011 10:58

December 13, 2011

There really is no difference between men and women's math abilities

[image error]

This article in io9 describes an in-depth study about the longstanding myth that there is a biological difference in how the men and women approach math. The conclusion:

"None of our findings suggest that an innate biological difference

between the sexes is the primary reason for a gender gap in math

performance at any level. Rather, these major international studies

strongly suggest that the math-gender gap, where it occurs, is due to

sociocultural factors that differ among countries, and that these

factors can be changed."

Essentially, as the study illustrates, the solution to any gender gap is to "increase the number of math teachers in middle and high schools, decrease the number of children currently living in poverty, and take greater steps to reduce gender inequity."

This article in io9 describes an in-depth study about the longstanding myth that there is a biological difference in how the men and women approach math. The conclusion:

"None of our findings suggest that an innate biological difference

between the sexes is the primary reason for a gender gap in math

performance at any level. Rather, these major international studies

strongly suggest that the math-gender gap, where it occurs, is due to

sociocultural factors that differ among countries, and that these

factors can be changed."

Essentially, as the study illustrates, the solution to any gender gap is to "increase the number of math teachers in middle and high schools, decrease the number of children currently living in poverty, and take greater steps to reduce gender inequity."

Published on December 13, 2011 14:04

December 11, 2011

Poor Norway. (Go butter!)

This sounds like something the Onion would have thought up: apparently, Norway has eaten through it's entire stock of butter. The funniest sad news I've read in a while.

Thanks to Patrick Nielsen Hayden for the link.

Thanks to Patrick Nielsen Hayden for the link.

Published on December 11, 2011 08:35

December 6, 2011

Book giveaway

For those of you who have joined Goodreads, I have posted a giveaway. Anyone indicating an interest between now and February 28, 2012 will have a chance to receive one of two signed hardcover copies of my new YA novel GIL MARSH. There's more information here.

Good luck!

Published on December 06, 2011 05:43

November 28, 2011

Pie

This Thanksgiving, I offered to bring several pies from a local orchard.

"Would you like apple-caramel with walnuts?" I asked.

"Mmm," my niece said. "Apple, walnut, caramel!"

When I picked up the pies, they were still warm.

"Leave the boxes open to avoid condensation," I was instructed.

They smelled so good! I put them on the bottom shelf of our cupboard---safe from unwanted jostles or unintentional spills. Too safe.

Thanksgiving morning, an hour from home with another three and a half hours of driving to go, my spouse asked, "Did we ever pack the pies?"

Turning around wasn't an option. We stopped at a rest area, and I frantically placed one phone call after another. A friendly grocer answered. "We're open till four. And yes, we have plenty of pies."

We bought three---an apple-walnut, a pumpkin, and a coconut cream.

The food at my niece's was several shades of awesome---who knew turkey could be smoky, moist and wonderful? And there was more than enough dessert to go around. When I explained to her why the promised apple-caramel with walnuts wasn't there, she laughed.

"You're not fooling me. You just wanted to keep it for yourselves!"

I laughed, too. Because, you know. Apple, walnut, caramel. . . Mmmm.

"Would you like apple-caramel with walnuts?" I asked.

"Mmm," my niece said. "Apple, walnut, caramel!"

When I picked up the pies, they were still warm.

"Leave the boxes open to avoid condensation," I was instructed.

They smelled so good! I put them on the bottom shelf of our cupboard---safe from unwanted jostles or unintentional spills. Too safe.

Thanksgiving morning, an hour from home with another three and a half hours of driving to go, my spouse asked, "Did we ever pack the pies?"

Turning around wasn't an option. We stopped at a rest area, and I frantically placed one phone call after another. A friendly grocer answered. "We're open till four. And yes, we have plenty of pies."

We bought three---an apple-walnut, a pumpkin, and a coconut cream.

The food at my niece's was several shades of awesome---who knew turkey could be smoky, moist and wonderful? And there was more than enough dessert to go around. When I explained to her why the promised apple-caramel with walnuts wasn't there, she laughed.

"You're not fooling me. You just wanted to keep it for yourselves!"

I laughed, too. Because, you know. Apple, walnut, caramel. . . Mmmm.

Published on November 28, 2011 11:40

November 22, 2011

Theft, a time-honored tradition

Over at Write Up Our Alley I explain where I get ideas for my books. You can read the post here.

Published on November 22, 2011 10:00

November 21, 2011

November 18, 2011

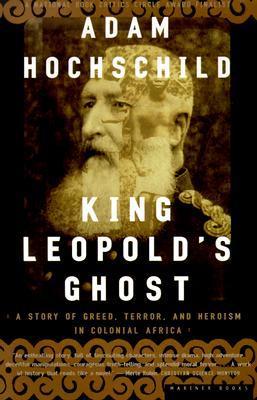

Tintin and King Leopold's Ghost

I read Adam Hochschild’s excellently written book, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, with fascination and dread. Here was a story I had only recently become aware of, the death of 10 million people at the hands of rapacious colonialists in the Congo.

I read Adam Hochschild’s excellently written book, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, with fascination and dread. Here was a story I had only recently become aware of, the death of 10 million people at the hands of rapacious colonialists in the Congo.King Leopold II of the Belgians appropriated the Congo basin as his own private property and exploited it for ivory and then rubber. Between 1885 and 1908, this vast region of Africa (77 times the size of Belgium) became killing fields while turning a profit for the king, conservatively estimated at 220 million francs of the time, or 1.1 billion in 1998 dollars.*

The terror he instituted (copied by other European powers in Africa) was based on forced labor. Native-born people were conscripted into a local army called “Force Publique,” run by white leaders using brutal treatment and terror. Garrisons of this army were marched from village to village with demands for “volunteers” (to work as porters, frequently in chains) and later for quotas of rubber. If they met resistance, they killed entire villages outright, or held women, elder leaders and children as hostages. The Force Publique conscripts were issued bullets, but were not permitted to hunt with them. They could only be used to kill people. So for each bullet issued, conscripts had to deliver a severed hand (usually smoked, to preserve it) to prove that it had been used for its intended purpose.

With a novel-like ear for storytelling, the book talks about the rise and end of Leopold’s rule, the many people involved in the fight against his brutality, and the experience of the Congolese people.

The colony was turned over to Belgium in 1908, but the story did not end there. Eventually, although not immediately, the Belgian colony became less brutal. But only marginally so, since until the 1950s its principal goal was to exploit the region’s riches, and it continued to use forced labor to do so. As late as the 1920s, missionaries reported continued depopulation and low birth rates as a result of the conscription of miners, the continued appropriation of land by colonists and companies, and the requirement that villagers plant specific, exportable, cash crops which never benefited the Congolese.**

So let’s talk about Tintin.

Hergé wrote Tintin in the Congo in 1931. It was reissued with new art and some editing in 1946. (Which is the version I read, in French, as a child.) In later years, Hergé would disavow the book as being an immature work of someone taught the racist and paternalistic view that Africans were like uncivilized children, and who lived at a time when big game hunting was popular.

Hergé wrote Tintin in the Congo in 1931. It was reissued with new art and some editing in 1946. (Which is the version I read, in French, as a child.) In later years, Hergé would disavow the book as being an immature work of someone taught the racist and paternalistic view that Africans were like uncivilized children, and who lived at a time when big game hunting was popular.The popularity of Tintin has been hard to resist, however. And eventually, publishers have reissued Tintin in the Congo, even over justified protests about its racism. Most recently they have put a sleeve on it explaining the times in which it was written, and have placed the volume in the adult graphic novel section.

But racism is only a part of the book’s problem. What Tintin in the Congo does is more insidious. It takes the view that Belgian colonialism was beneficial for the Congolese, and that white rulers were there to “civilize,” by word and action. Tintin (when not killing off animals) stops warring chiefs (with great derring-do) and shows the way for peace between the two villages. (He also stops an American gangster from stealing the diamonds from a mine, which, of course, belong to the white authorities.)

This paean to Belgian colonialism is galling. Later in Congo’s colonial history, Belgium would build more schools and work to improve health care (having marked success in dealing with sleeping sickness). It realized, belatedly, that the Congolese never benefitted from the colony’s vast riches, but the improvements were much too little, way too late. In 1960, after a rising tide of protests and unrest, Belgium officially ceded the colony to its people.

Tintin admirers will say that despite its flaws, the book still represents a work of Hergé’s genius, and it should be admired for its artistry, if not for its racist and colonialist content.

I cringe at this argument. It’s the one used for Birth of a Nation, a movie used by the Ku Klux Klan as a recruitment vehicle into the 1970s. It is a way of placing form over content, as if one were divorced from the other. If there is anything that a lifetime of reading comics has taught me, it is that the art and the text are inextricably linked. The content cannot be removed from the art.

King Leopold II was a master of deception and redirection. Tintin in the Congo would have served him well.

* The exact figure is unknown. When the international outcry at King Leopold II’s administration forced him to turn the Congo over to Belgium, he destroyed all the state records of his rule. The effort kept furnaces burning in Brussels for eight days. The monetary estimate is based on the deflated reports he made to the Belgian government; those shipping records that were not destroyed; and the Congo profits he used to build a large number of public buildings, monuments, personal villas and castles, to finance his lavish lifestyle, and to pay retainers and bribes both in Belgium and abroad.

** Ironically, the Great Depression had a beneficial effect for Congo’s people: with oversupply and the precipitous drop in commodity prices, labor demands dropped, and many Congolese were allowed to return to their homes.

[Thanks to Mitali Perkins for noting the re-issuance of Tintin in the Congo.]

Published on November 18, 2011 13:15