A.C.E. Bauer's Blog, page 8

February 27, 2012

Happy birthday!

Today is Gil Marsh 's official release date, which is both very exciting and, well, boring. It’s exciting because, after months and months of build-up, the book is finally available on shelves and folks can purchase it. (Yay!) The boring part is that nothing else happens. (Ho hum.)

Which is why authors have release parties—someone has to celebrate!

Come join me and other celebrants at the Alphabet Garden Bookstore in Cheshire, Connecticut on Saturday March 10 at 11:30 a.m. I’ll read some from the new book, answer questions, and we’ll generally have fun. (Yippee!)

Published on February 27, 2012 21:07

February 14, 2012

Meeting Gilgamesh

The tablets were so small.

The tablets were so small.I recently went to an exhibit at the Sterling Memorial Library at Yale entitled “Monarchs of Mesopotamia.” On display were cuneiform tablets* spanning over one thousand years, including one of the tablets from the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The tablets’ minute size surprised me more than anything else. The Gilgamesh tablet, one of the largest, measures about about 7 1/8 inches by 6 ½ inches—similar in size to a trade paperback book. Most of the others on display were much smaller. The cuneiform script was tiny and cramped.

But each tablet was filled with information.

One describes how a king who had a great deal of difficulty conceiving a child, bemoaned the lack of filial devotion once he has children. “You may have six, or seven, or eight children. They are not worth it!” In another tablet, a king administering justice orders that a murderer be put death in the same way he killed his victim, by being thrown into an oven. A minuscule tablet announces the beginning of the harvest season couched in terms of the magnificence of the king.

The one from the Epic of Gilgamesh kept me the longest. The third tablet of twelve, it concerns the episode where Gilgamesh has decided to kill the giant Humbaba despite his friend Enkidu’s warnings. The bulk of the tablet relates advice given by the elders of Uruk, Gilgamesh's plea to his mother (a goddess) to intervene with the sun god on his behalf, and her decision to adopt Enkidu as her own son.

This is not the most riveting moment of the story, yet seeing this over-three-thousand-year-old document, broken and incomplete as it was, I was awestruck. How often do you get to meet one of your heroes?

* Ancient Sumerian scribes wrote on clay. They used a wedged-shaped stylus that they pushed into the soft clay to create symbols. On occasion, when a permanent record was needed, the clay might be fired.

Published on February 14, 2012 07:23

February 11, 2012

Real men and pink suits

Charles M. Blow, the New York Times visual Op-Ed columnist, wrote an excellent column today about Americans' perceptions of masculinity, and the corrosive effect it can have on individuals.

Anyone perceived as not fitting this ideal, an impossible one to attain, is liable to be labeled as other. Men in pink suits are to be laughed at, or beaten. Anyone perceived as fitting a homosexual stereotype is a walking target--to which a third of school-aged boys can attest.

The whole column is worth reading. It's called Real Men and Pink Suits.

[M]asculinity is wide enough and deep enough for all [men] to fit in it. But society in general, and male culture in particular, is constantly working to render it narrow and shallow. We have shaved the idea of manhood down to an unrealistic definition that few can fit it in with the whole of who they are, not without severe constriction or self-denial.

Anyone perceived as not fitting this ideal, an impossible one to attain, is liable to be labeled as other. Men in pink suits are to be laughed at, or beaten. Anyone perceived as fitting a homosexual stereotype is a walking target--to which a third of school-aged boys can attest.

Start with this fact: The truest measure of a man, indeed of a person, is not whom he lies down with but what he stands up for. If we must be judged, let it be in this way.

The whole column is worth reading. It's called Real Men and Pink Suits.

Published on February 11, 2012 07:10

February 4, 2012

When-I'm-Going-To-Be-Too-Busy-To-Cook-Later Stew

When the weather gets cold, and I want something hearty and tasty for dinner but can't hang around the kitchen all day, I sometimes make this stew.

The idea is simple: meat, root vegetables, plenty of liquid, and a long, slow cook---there are as many variations as there are cooks. The version I use has many virtues, not the least being that once you’ve assembled all the ingredients in one pot, you don’t have to attend to it, except to turn down the oven heat once. It’s the kind of thing I make before I leave for a busy afternoon when I won’t be home until just around when we want to eat. This will feed 4 to 5 hungry people.

1 lb veal stew meat (or other stew meat), cut into chunks

12-16 oz aromatic sausage (sweet Italian; chicken with mushrooms; whatever you like), cut into chunks

2 onions, peeled, halved lengthwise, and sliced into lengths

2 cloves garlic, peeled and quartered

1 lb baby carrots

5 potatoes, peeled and quartered

Salt and pepper to taste

1 tsp coriander seeds (optional)

1 bay leaf (optional)

2-3 cups chicken or other soup stock (canned will work just fine)

Preheat oven to 300 F.

In a large oven-proof pot with a well-fitting lid, layer the onion, garlic, veal, sausage, carrots and last potatoes. Sprinkle with salt, pepper, and coriander seeds. Put in bay leaf. Pour in enough stock so that everything is at least partially submerged. (The onions and carrots will release liquid, too.) Cover and place pot on center rack of oven.

After 1 hour, turn oven heat down to 220 F. Cook for several hours more—at least 1, as many as 5 or 6 or whenever you finally can get to the pot. The flavors will only intensify with time. It’ll make a fair amount of liquid which I store in a jar and use as leftover broth, really delicious with leftover rice or noodles.

Note: If you don’t have broth, use 2 to 3 medium onions per lb. of meat plus 1/4 cup of water (to prevent sticking at the beginning), and you should produce more than enough liquid as it cooks.

The idea is simple: meat, root vegetables, plenty of liquid, and a long, slow cook---there are as many variations as there are cooks. The version I use has many virtues, not the least being that once you’ve assembled all the ingredients in one pot, you don’t have to attend to it, except to turn down the oven heat once. It’s the kind of thing I make before I leave for a busy afternoon when I won’t be home until just around when we want to eat. This will feed 4 to 5 hungry people.

1 lb veal stew meat (or other stew meat), cut into chunks

12-16 oz aromatic sausage (sweet Italian; chicken with mushrooms; whatever you like), cut into chunks

2 onions, peeled, halved lengthwise, and sliced into lengths

2 cloves garlic, peeled and quartered

1 lb baby carrots

5 potatoes, peeled and quartered

Salt and pepper to taste

1 tsp coriander seeds (optional)

1 bay leaf (optional)

2-3 cups chicken or other soup stock (canned will work just fine)

Preheat oven to 300 F.

In a large oven-proof pot with a well-fitting lid, layer the onion, garlic, veal, sausage, carrots and last potatoes. Sprinkle with salt, pepper, and coriander seeds. Put in bay leaf. Pour in enough stock so that everything is at least partially submerged. (The onions and carrots will release liquid, too.) Cover and place pot on center rack of oven.

After 1 hour, turn oven heat down to 220 F. Cook for several hours more—at least 1, as many as 5 or 6 or whenever you finally can get to the pot. The flavors will only intensify with time. It’ll make a fair amount of liquid which I store in a jar and use as leftover broth, really delicious with leftover rice or noodles.

Note: If you don’t have broth, use 2 to 3 medium onions per lb. of meat plus 1/4 cup of water (to prevent sticking at the beginning), and you should produce more than enough liquid as it cooks.

Published on February 04, 2012 11:28

February 2, 2012

Gil Marsh on Facebook

Published on February 02, 2012 12:50

February 1, 2012

School Library Journal weighs in

School Library Journal reviewed Gil Marsh and had some nice things to say.

If the strange names, the story of male friendship, and mythological quest sound familiar, it’s because Bauer is retelling the epic of Gilgamesh, supposedly the oldest story every written. This contemporary version is loosely based on the legend, with names, places, and elements throughout that echo the original. The novel is plot-driven and retains a mythlike quality. A worthy addition.

Thank you SLJ!

Published on February 01, 2012 09:48

January 19, 2012

Ooh. Pretty!

Published on January 19, 2012 11:58

January 16, 2012

Losing this reader's trust

I read Habibi by Craig Thompson eagerly. It had received incredible buzz. The cover was stunning. Leafing through, I was enchanted by the gorgeous calligraphy. The setting was a fictional Middle East—a region I have mainly read about in the context of war, political upheaval, or dead civilizations. I was intrigued.

I read Habibi by Craig Thompson eagerly. It had received incredible buzz. The cover was stunning. Leafing through, I was enchanted by the gorgeous calligraphy. The setting was a fictional Middle East—a region I have mainly read about in the context of war, political upheaval, or dead civilizations. I was intrigued.At first, the art and clever storytelling (of which the art is integral) swept me up. The narrative occurs on many levels. At its base is the love story of a girl and a boy who escape slavery only to be recaptured in cruel ways. Woven in are stories from the Qur’an, the Old and New Testament, and from the Thousand and One Nights; an exploration of numerology and Arabic calligraphy; an indictment of the ecological destruction wrought on water systems and on the desert; and a swipe at racism and the dismal status of women.

Something nagged at me, though.

I know precious little about Arabic culture, close to nothing about the Qur’an, and am equally uneducated about desert ecology. But I do know that all Arab men are not brutes. All Arab women are not sex objects. Parents love their children—in all cultures.

Granted, storytelling would be boring if protagonists only came from happy homes, had caring parents, and lived in a just world. Dystopia is a popular genre, after all. But Habibi promises something else: a view into another culture and another world.

And much of the book feels real. Although at first it isn’t clear when this tale takes place, we are clued in early that this is not the ancient past: there are car parts and a boat’s engine room. It's plausible to start the story with a child bride and slavery---unfortunately both still exist. As more of the narrative gets woven in, we encounter Mohammed in a respectful portrayal, and find Bible and Qur’an stories laid out with thought. The forays into the power of writing and numbers seem to be based on extensive research.

I am led to believe that there is truth here—the story may be fictitious, but the details are taken from life.

But they aren’t.

Women are repeatedly defined by their sexuality, with an almost pin-up fascination. Rape is portrayed as a turn-on. Characters are one stereotype after another (the Arab brute, the soulless soldier, the lustful black servant, the rapacious sultan, the fisherman-fool)---too much of the cast comes from central casting. Which makes me wonder, what does the author know about the culture he is depicting? How much of the set is false? And if the set isn't quite right, how can I trust his depiction of what is happening to the desert? Or trust that there aren’t errors in his researched sacred stories and calligraphy?

It’s not enough to get a culture’s art right. Culture is more than a people’s art. If you want me to trust that you are telling me something true, you have to get the people right, too.

Published on January 16, 2012 19:12

January 9, 2012

Archives

Over at Write Up Our Alley I blog about how I keep archives of my work on paper, and why. You can read the post here.

Published on January 09, 2012 17:35

January 6, 2012

Why I don't give review stars

I joined Goodreads* a while ago and only recently have begun posting reviews on the site. Though I can give each book 1 to 5 stars, I decided early on that I wouldn’t give any. I write what I think, but I leave off ranking the books.

Why?

I do have strong opinions about what I like or don’t like. But I find star-ranking reviews to be misleading.

Let me give some examples—three books that I have recently finished (“finished” being a term of art since I only read, from beginning to end, two of the books).

I have tried and failed to read A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin several times now. I’ve picked it up, made my way through the first chapter, put it down vowing to continue reading, but then I was invariably distracted by something else on my shelves and didn’t get back to it. This time I made it part way into the second chapter—it took me three sittings. On the fourth, I read half a page and wondered why I was forcing myself to read something I was clearly not enjoying. That’s when I decided I had finished with the book.

I have tried and failed to read A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin several times now. I’ve picked it up, made my way through the first chapter, put it down vowing to continue reading, but then I was invariably distracted by something else on my shelves and didn’t get back to it. This time I made it part way into the second chapter—it took me three sittings. On the fourth, I read half a page and wondered why I was forcing myself to read something I was clearly not enjoying. That’s when I decided I had finished with the book.

I view this as a personal defeat. There are many people, whose reading tastes I respect, who consider the book to be one of the best stories of their young adult lives—a book, for a few, that drew them into the fantasy genre. And Ursula Le Guin is the grande dame of SF & F. There is much I can learn from her work. Unfortunately, what I learned is that there’s something about the voice in that story that totally turned me off—it prevented me from connecting with any of the characters. As a result, each new plot development became glaring: I could see a fall being set up and all I wanted to do was cringe.

If I were to rank the book among the ones in my library, I’d probably give it one star. Yet, in the greater scheme, I know that so many people have loved the tale that it has become a classic. Clearly the story has captured people’s imaginations—and the book’s voice is far less important to them. In fact, folks may like it, or love it, even.

My ranking would be an outlier—i.e., on the extreme of the scale. And my problem with the book is entirely idiosyncratic. I might have thoroughly enjoyed the plot if I hadn’t been so turned off by the voice. A single star would not convey any of this information—and might mislead a reader who has a different taste for voices.

But it’s not only that the stars don’t convey important information. Stars mean different things to different people.

Two Hot Dogs with Everything by Paul Haven is a middle grade novel aimed squarely for the middle grade reader. It is filled with amusing baseball lore, quirky characters, a satisfyingly evil villain, and a dollop of magic. Now, although I like baseball well enough, I do not love the sport, and I find game play-by-plays tedious. My review for Goodreads: “A fun book for those who love baseball.”

Two Hot Dogs with Everything by Paul Haven is a middle grade novel aimed squarely for the middle grade reader. It is filled with amusing baseball lore, quirky characters, a satisfyingly evil villain, and a dollop of magic. Now, although I like baseball well enough, I do not love the sport, and I find game play-by-plays tedious. My review for Goodreads: “A fun book for those who love baseball.”

In fact, for those who love baseball, this book might be worth four or five stars. On my shelves, it’d probably get three. And if I gave it three, would it convey how wonderful I think the book would be to a baseball fan? I need separate star ratings: 5 stars for the baseball lover; 3 stars for those with only a passing interest in the sport; 1 star for people who dislike sports.

And what about the books that I wholeheartedly love? The very things that please me might leave someone else indifferent, or be distasteful to others.

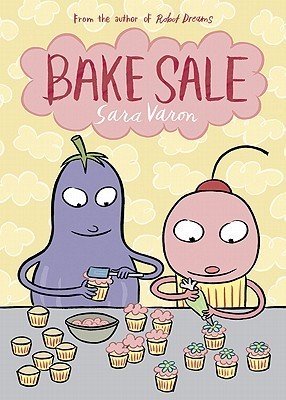

Bake Sale by Sara Varon is the example here. It’s a graphic novel set in a Brooklyn populated by food items that live human lives. The main character is a cupcake who owns a bakery. His best friend is an eggplant who paints (buildings and such). Both play in a band with a doughnut, an egg, a pear, and an avocado.

Bake Sale by Sara Varon is the example here. It’s a graphic novel set in a Brooklyn populated by food items that live human lives. The main character is a cupcake who owns a bakery. His best friend is an eggplant who paints (buildings and such). Both play in a band with a doughnut, an egg, a pear, and an avocado.

What follows is an affecting story about friendship. We get to tour some of the memorable if less famous wonders of Brooklyn and NYC while learning a great deal about baking. The art is simple and colorful but cleverly detailed. The only (non-food) human characters appear on a handbill advertising a boxing match. There are plenty of animals—who remain animals—which leads to the wonderful incongruity of a giant cooked turkey leg walking a dog in the park.

The gentle story will please children, and adults who revel in graphic novels (or yummy recipes). If I were to grant stars, the book would get five.

But hold on. I am a fan of naive art. I am amused by the idea of a bag of sugar eating a brownie, but someone else might be turned off by food eating food. The point for me is to revel in the absurdity while capturing the human story portrayed by the characters. My five stars would mislead a reader who might view the book as a bizarre paean to cannibalism.

My point in all of this is that what affects my likes and dislikes is personal. Though others may agree with me, it’s just as possible that what matters to me may not matter to anyone else. No star can convey personal quirks—and so I prefer to leave them out entirely.

*For those unfamiliar with Goodreads, it’s a social site where members post information about books they read.

Why?

I do have strong opinions about what I like or don’t like. But I find star-ranking reviews to be misleading.

Let me give some examples—three books that I have recently finished (“finished” being a term of art since I only read, from beginning to end, two of the books).

I have tried and failed to read A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin several times now. I’ve picked it up, made my way through the first chapter, put it down vowing to continue reading, but then I was invariably distracted by something else on my shelves and didn’t get back to it. This time I made it part way into the second chapter—it took me three sittings. On the fourth, I read half a page and wondered why I was forcing myself to read something I was clearly not enjoying. That’s when I decided I had finished with the book.

I have tried and failed to read A Wizard of Earthsea by Ursula Le Guin several times now. I’ve picked it up, made my way through the first chapter, put it down vowing to continue reading, but then I was invariably distracted by something else on my shelves and didn’t get back to it. This time I made it part way into the second chapter—it took me three sittings. On the fourth, I read half a page and wondered why I was forcing myself to read something I was clearly not enjoying. That’s when I decided I had finished with the book.I view this as a personal defeat. There are many people, whose reading tastes I respect, who consider the book to be one of the best stories of their young adult lives—a book, for a few, that drew them into the fantasy genre. And Ursula Le Guin is the grande dame of SF & F. There is much I can learn from her work. Unfortunately, what I learned is that there’s something about the voice in that story that totally turned me off—it prevented me from connecting with any of the characters. As a result, each new plot development became glaring: I could see a fall being set up and all I wanted to do was cringe.

If I were to rank the book among the ones in my library, I’d probably give it one star. Yet, in the greater scheme, I know that so many people have loved the tale that it has become a classic. Clearly the story has captured people’s imaginations—and the book’s voice is far less important to them. In fact, folks may like it, or love it, even.

My ranking would be an outlier—i.e., on the extreme of the scale. And my problem with the book is entirely idiosyncratic. I might have thoroughly enjoyed the plot if I hadn’t been so turned off by the voice. A single star would not convey any of this information—and might mislead a reader who has a different taste for voices.

But it’s not only that the stars don’t convey important information. Stars mean different things to different people.

Two Hot Dogs with Everything by Paul Haven is a middle grade novel aimed squarely for the middle grade reader. It is filled with amusing baseball lore, quirky characters, a satisfyingly evil villain, and a dollop of magic. Now, although I like baseball well enough, I do not love the sport, and I find game play-by-plays tedious. My review for Goodreads: “A fun book for those who love baseball.”

Two Hot Dogs with Everything by Paul Haven is a middle grade novel aimed squarely for the middle grade reader. It is filled with amusing baseball lore, quirky characters, a satisfyingly evil villain, and a dollop of magic. Now, although I like baseball well enough, I do not love the sport, and I find game play-by-plays tedious. My review for Goodreads: “A fun book for those who love baseball.”In fact, for those who love baseball, this book might be worth four or five stars. On my shelves, it’d probably get three. And if I gave it three, would it convey how wonderful I think the book would be to a baseball fan? I need separate star ratings: 5 stars for the baseball lover; 3 stars for those with only a passing interest in the sport; 1 star for people who dislike sports.

And what about the books that I wholeheartedly love? The very things that please me might leave someone else indifferent, or be distasteful to others.

Bake Sale by Sara Varon is the example here. It’s a graphic novel set in a Brooklyn populated by food items that live human lives. The main character is a cupcake who owns a bakery. His best friend is an eggplant who paints (buildings and such). Both play in a band with a doughnut, an egg, a pear, and an avocado.

Bake Sale by Sara Varon is the example here. It’s a graphic novel set in a Brooklyn populated by food items that live human lives. The main character is a cupcake who owns a bakery. His best friend is an eggplant who paints (buildings and such). Both play in a band with a doughnut, an egg, a pear, and an avocado.What follows is an affecting story about friendship. We get to tour some of the memorable if less famous wonders of Brooklyn and NYC while learning a great deal about baking. The art is simple and colorful but cleverly detailed. The only (non-food) human characters appear on a handbill advertising a boxing match. There are plenty of animals—who remain animals—which leads to the wonderful incongruity of a giant cooked turkey leg walking a dog in the park.

The gentle story will please children, and adults who revel in graphic novels (or yummy recipes). If I were to grant stars, the book would get five.

But hold on. I am a fan of naive art. I am amused by the idea of a bag of sugar eating a brownie, but someone else might be turned off by food eating food. The point for me is to revel in the absurdity while capturing the human story portrayed by the characters. My five stars would mislead a reader who might view the book as a bizarre paean to cannibalism.

My point in all of this is that what affects my likes and dislikes is personal. Though others may agree with me, it’s just as possible that what matters to me may not matter to anyone else. No star can convey personal quirks—and so I prefer to leave them out entirely.

*For those unfamiliar with Goodreads, it’s a social site where members post information about books they read.

Published on January 06, 2012 14:10