A.C.E. Bauer's Blog, page 5

October 11, 2012

To my Minnesotan readers (and Maine, and Washington, and wherever you live)

This week my daughter and I are volunteering at Minnesotans United for All Families in Minneapolis, to work against an amendment to the Minnesota constitution that would ban gay marriage. It has been an exhausting but extremely rewarding experience.

Why, you may ask, would someone from Connecticut, someone from a state where gay marriage is legal, fly halfway around the country to volunteer? After all, how does it affect me?

The simplest answer is that I come from a large extended family. We have settled everywhere in the U.S., from the Northeast, to the South, the Midwest, the Rockies, the Southwest, the West Coast, and everywhere in between.

And yes, I have family in Minnesota, too. And one of my children studies here.

If she loves a woman, then I will embrace her partner--I will love whom she loves. That's how families are built.

And if she decides to marry a woman, I'd love to have her come home and get married in Connecticut. But she shouldn't have to. She should be able, like every married person in our large family, to chose a wonderful spot that has meaning to her and her spouse to be. And once she is married, regardless of whom she marries, the marriage should be recognized, everywhere.

This last week I heard a heart-wrenching story. A man told me how he had been with his partner for over 30 years. They had signed one contract and legal document after another to make sure that in case of illness or death, they could each take care of each other as they would have wished. Despite that, despite every care and foresight, when his partner died, he wasn't permitted to move his partner's body: they had to get his partner's elderly mother to give approval. This is recently. In Minnesota.

No one should have to face that. No one in my family should have to face that. None of the children in my family should have to even think about that.

Wherever you may live, think about how banning gay marriage hurts people. Real people.

I am here because I will love whomever my children love. And I want them to be able to do so freely.

Why, you may ask, would someone from Connecticut, someone from a state where gay marriage is legal, fly halfway around the country to volunteer? After all, how does it affect me?

The simplest answer is that I come from a large extended family. We have settled everywhere in the U.S., from the Northeast, to the South, the Midwest, the Rockies, the Southwest, the West Coast, and everywhere in between.

And yes, I have family in Minnesota, too. And one of my children studies here.

If she loves a woman, then I will embrace her partner--I will love whom she loves. That's how families are built.

And if she decides to marry a woman, I'd love to have her come home and get married in Connecticut. But she shouldn't have to. She should be able, like every married person in our large family, to chose a wonderful spot that has meaning to her and her spouse to be. And once she is married, regardless of whom she marries, the marriage should be recognized, everywhere.

This last week I heard a heart-wrenching story. A man told me how he had been with his partner for over 30 years. They had signed one contract and legal document after another to make sure that in case of illness or death, they could each take care of each other as they would have wished. Despite that, despite every care and foresight, when his partner died, he wasn't permitted to move his partner's body: they had to get his partner's elderly mother to give approval. This is recently. In Minnesota.

No one should have to face that. No one in my family should have to face that. None of the children in my family should have to even think about that.

Wherever you may live, think about how banning gay marriage hurts people. Real people.

I am here because I will love whomever my children love. And I want them to be able to do so freely.

Published on October 11, 2012 09:23

October 3, 2012

I just call them comics

Yesterday, I managed to catch the Colin McEnroe Show on my local NPR station where he interviewed Nathan Englander (of What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank fame), and graphic novelist Marc Siegel. As aficionados of the show know, one of the things not to be missed is Chion (pronounced "cayonne") Wolf's introductions. Yesterday's was no exception.

You can hear her entire 30-second introduction by playing the beginning of the interview found on this page.

I will never think of graphic novels in quite the same way again.

You can hear her entire 30-second introduction by playing the beginning of the interview found on this page.

I will never think of graphic novels in quite the same way again.

Published on October 03, 2012 08:54

September 28, 2012

Because earworms are meant to be shared

Published on September 28, 2012 11:16

September 15, 2012

I feel like a deity

Published on September 15, 2012 16:51

September 14, 2012

Branford Reads

On Saturday September 15 I'll be at the BranfordReads festival from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. on the Branford Green, in Branford, Connecticut. The celebration includes presentations by a host of authors (I present at 12:30), book signings, puzzle contests, a Brainquest challenge, a silent auction, food, music, and at 2 p.m. there will be an award ceremony honoring the top summer readers from Branford public schools. Come join the fun!

Published on September 14, 2012 05:53

August 14, 2012

Hello, blogging again

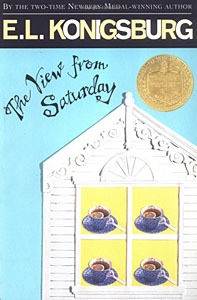

It's still warm out, and I can't promise that I'll be prolific around here. (Plus I'm chugging away at the rough draft of a new novel, which is eating up filling up my precious writing time.) But I did post on Write Up Our Alley about one of my favorite books, The View from Saturday, and about its author E. L. Konigsburg, who happens to be one of my literary heroes. You can read the entire post here.

It's still warm out, and I can't promise that I'll be prolific around here. (Plus I'm chugging away at the rough draft of a new novel, which is eating up filling up my precious writing time.) But I did post on Write Up Our Alley about one of my favorite books, The View from Saturday, and about its author E. L. Konigsburg, who happens to be one of my literary heroes. You can read the entire post here.

Published on August 14, 2012 12:14

July 20, 2012

Summer doldrums

It's that time of year again.

It's hot. It's nice out. I'm not on the computer.

It's all good though. I'm working and reading. But it'll be quiet here for awhile longer.

Catch up with you later, around mid-August.

Hope you are all having a good summer.

It's hot. It's nice out. I'm not on the computer.

It's all good though. I'm working and reading. But it'll be quiet here for awhile longer.

Catch up with you later, around mid-August.

Hope you are all having a good summer.

Published on July 20, 2012 05:43

July 2, 2012

Sticking to it

I sat on the porch of our cabin in Quebec, admiring the view with my father.

He was an old man, then, ailing. Although we did not know it at the time, this would be his last visit to the lake. Professionally, it had been a trying, depressing time for me. I had been submitting manuscripts to editors for years, and other than one short story for Ladybug Magazine, no one seemed interested in what I was writing. But on that sunny afternoon, we were happy, quiet company, glad to sit and breathe and spend time with each other.

“Alice,” he said, “did I ever tell you what it was like when I first started working in Montreal?”

Papa was poor: he had arrived as an immigrant with almost nothing. There were days when he survived on a single meal. He took up a job selling tools to hardware stores. He was given samples by the company, and he went around Montreal, from store to store, hoping to make a sale. Every day he’d make sure to visit as many stores as he could fit in, show his wares, and move on the next one.

“I didn’t sell anything. But as long as I was going from store to store, I was doing my job.”

One day, he arrived at a store he had visited a few times before, and spoke to the owner.

“You know,” the owner said, “I won’t buy what you’re selling. I get my tools from another manufacturer, and I like what they make. But you’re a nice man. So let me tell you about the store a few blocks that way. They’ll be interested in what you have to show.”

My father thanked him and went to the store the owner had told him about. He made his first sale that day.

“After that, I didn’t make lots of sales right away. But I made more. And I stuck with it because that was my job. I think I did okay in the end.”

We each have our heroes. Papa was one of mine.

He was an old man, then, ailing. Although we did not know it at the time, this would be his last visit to the lake. Professionally, it had been a trying, depressing time for me. I had been submitting manuscripts to editors for years, and other than one short story for Ladybug Magazine, no one seemed interested in what I was writing. But on that sunny afternoon, we were happy, quiet company, glad to sit and breathe and spend time with each other.

“Alice,” he said, “did I ever tell you what it was like when I first started working in Montreal?”

Papa was poor: he had arrived as an immigrant with almost nothing. There were days when he survived on a single meal. He took up a job selling tools to hardware stores. He was given samples by the company, and he went around Montreal, from store to store, hoping to make a sale. Every day he’d make sure to visit as many stores as he could fit in, show his wares, and move on the next one.

“I didn’t sell anything. But as long as I was going from store to store, I was doing my job.”

One day, he arrived at a store he had visited a few times before, and spoke to the owner.

“You know,” the owner said, “I won’t buy what you’re selling. I get my tools from another manufacturer, and I like what they make. But you’re a nice man. So let me tell you about the store a few blocks that way. They’ll be interested in what you have to show.”

My father thanked him and went to the store the owner had told him about. He made his first sale that day.

“After that, I didn’t make lots of sales right away. But I made more. And I stuck with it because that was my job. I think I did okay in the end.”

We each have our heroes. Papa was one of mine.

Published on July 02, 2012 10:34

June 14, 2012

Snow, vodka, and the nature of stories

My great-uncle Muniu was a barrel of a man. He was the kind of person who filled a room just by walking into it—maybe because he spoke so loud; maybe because he was such a storyteller; maybe because he was rock solid, in all the ways you want someone to be. He lived in Poland until the Germans invaded and shipped his family and village off to Sorbibor.

Muniu managed to avoid the transport. I don’t know how. But his escape from the Germans only landed him in the Soviet army. He was press-ganged, along with any hale young Pole the Russians could capture, and put into service driving a truck.

I was a kid when Muniu died, but I still can recall the description of the hardships. At one point, stationed at a siege, all they had to eat was shoe leather—that, and snow.

Years later my aunt told me a story. Apparently, while in the Soviet army, Muniu got a raging toothache. In agony, he stole a pair of plyers, took a swig of alcohol, and yanked his own tooth out.

When the officer in charge found out, he threatened to court-martial him. “This is treason! First, you engaged in a medical procedure without getting the permission of the Committee. And second, worse, you hid from the Committee the fact that you have medical training!” Of course, Muniu had never had any medical training.

Rather than punish him, the commander handed him a pair of plyers and a bottle of vodka, and assigned him to the position of troop dentist. Muniu spent the remainder of the war pulling Soviet soldiers’ teeth, when not manning the truck.

Fast forward to the 1950s in Montreal, Quebec. My aunt, a girl, had a toothache. It was Sunday and everything in Montreal had shut down, as it always did. But Muniu took my aunt in his car and went in search of a dentist. As he drove around and around on this thankless errand, my aunt, in pain, heard him mutter, “All I need is a pair of plyers.”

A couple of years ago, I told these two related stories to a dear friend. Katherine's family hails from Russia, and she is fluent in Russian. As any storyteller would, I took what I knew of Muniu, and what I had heard in childhood and from my aunt, and embellished. I placed his toothache at the time of the siege—Leningrad, I said, although I acknowledged it could have been Stalingrad. The rest I kept more or less as I remembered.

Katherine's eyes danced. “It should be the Leningrad siege,” she told me. “Because that was St. Petersburg, named after Peter the Great. And you know that Peter the Great was an amateur dentist, and a patron of dentistry for the Russian army." Where else should my uncle have been assigned the job?

Tickled, in my next letter to my aunt I relayed what Katherine had told me. My aunt was thoroughly amused, not only by Katherine’s take on it, but in how the story had mutated in my telling.

You see, she did not recollect any siege: she thought the episode had been “in the middle of the vast Russian nowhere.” And Muniu didn’t have a bottle of vodka, since none was to be had at the time—he had numbed his mouth with snow. The officer gave him his own pair of plyers and told him to take care of the soldiers’ teeth. “You can use as much snow as you like!”

The storyteller in me is thrilled. The punch line is much better with snow than with vodka. The Leningrad/Peter the Great connection, however, has to stay at least in some way---it's too wonderful to ignore.

I think my uncle Muniu would approve.

Muniu managed to avoid the transport. I don’t know how. But his escape from the Germans only landed him in the Soviet army. He was press-ganged, along with any hale young Pole the Russians could capture, and put into service driving a truck.

I was a kid when Muniu died, but I still can recall the description of the hardships. At one point, stationed at a siege, all they had to eat was shoe leather—that, and snow.

Years later my aunt told me a story. Apparently, while in the Soviet army, Muniu got a raging toothache. In agony, he stole a pair of plyers, took a swig of alcohol, and yanked his own tooth out.

When the officer in charge found out, he threatened to court-martial him. “This is treason! First, you engaged in a medical procedure without getting the permission of the Committee. And second, worse, you hid from the Committee the fact that you have medical training!” Of course, Muniu had never had any medical training.

Rather than punish him, the commander handed him a pair of plyers and a bottle of vodka, and assigned him to the position of troop dentist. Muniu spent the remainder of the war pulling Soviet soldiers’ teeth, when not manning the truck.

Fast forward to the 1950s in Montreal, Quebec. My aunt, a girl, had a toothache. It was Sunday and everything in Montreal had shut down, as it always did. But Muniu took my aunt in his car and went in search of a dentist. As he drove around and around on this thankless errand, my aunt, in pain, heard him mutter, “All I need is a pair of plyers.”

A couple of years ago, I told these two related stories to a dear friend. Katherine's family hails from Russia, and she is fluent in Russian. As any storyteller would, I took what I knew of Muniu, and what I had heard in childhood and from my aunt, and embellished. I placed his toothache at the time of the siege—Leningrad, I said, although I acknowledged it could have been Stalingrad. The rest I kept more or less as I remembered.

Katherine's eyes danced. “It should be the Leningrad siege,” she told me. “Because that was St. Petersburg, named after Peter the Great. And you know that Peter the Great was an amateur dentist, and a patron of dentistry for the Russian army." Where else should my uncle have been assigned the job?

Tickled, in my next letter to my aunt I relayed what Katherine had told me. My aunt was thoroughly amused, not only by Katherine’s take on it, but in how the story had mutated in my telling.

You see, she did not recollect any siege: she thought the episode had been “in the middle of the vast Russian nowhere.” And Muniu didn’t have a bottle of vodka, since none was to be had at the time—he had numbed his mouth with snow. The officer gave him his own pair of plyers and told him to take care of the soldiers’ teeth. “You can use as much snow as you like!”

The storyteller in me is thrilled. The punch line is much better with snow than with vodka. The Leningrad/Peter the Great connection, however, has to stay at least in some way---it's too wonderful to ignore.

I think my uncle Muniu would approve.

Published on June 14, 2012 10:24

June 13, 2012

10 (subjective) rules to survive waiting rooms

Rule #1: The book shouldn’t be depressing.

Reading is my number one occupation in waiting rooms. Something riveting and escapist is best. If not, research for something I’m working on is also good.

Rule #2: Always bring a pen and notebook.

Because I’ll need to take notes on that research. Or, if not doing research, maybe I’ll have the presence of mind to work on my most recent project, or a blog piece.

Rule #3: Sleeping is an option.

No one cares if you fall asleep in a waiting room. Most people wish they could do the same. Snoring, however, is bad form.

Rule #4: Don’t hog.

If the waiting room is busy, use one chair.

Rule #5: The receptionist will let you use a bathroom, if you ask.

This comes in handy, especially if the wait is long.

Rule #6: You don’t have to carry a conversation.

People in waiting rooms tend not to be happy people. No one expects you to be conversational. Don’t be rude, of course, but if you’d rather not talk, an acknowledgment, small smile and return to your reading of choice usually is signal enough that you’d rather not talk.

Corollary: If you want to talk, you might not find welcome listeners.

Rule #7: Eat your lunch elsewhere.

Seriously. That’s why hospitals have cafeterias. Bad enough you have to wait. Worse is smelling someone’s meal while you're hungry. Worst is being sick and having to smell food that increases your nausea.

Rule #8: If you like to people watch, be discreet.

This is where listening is better than looking. But really. Is it any of your business?

Rule #9: It’ll smell funny.

There’s nothing you can do about it.

Rule #10: The wait will come to an end.

I find this especially useful to remember if I didn’t follow rules 1 and 2, and can’t sleep. There are just so many times I’ll want to read the posted notices. Magazines get boring. And I really, really, REALLY dislike the noise from TVs. But sitting back and working out a problem about a novel, daydreaming about what else I could be doing, or just relaxing is infinitely better than obsessively checking my watch and wondering, how much longer do I have to wait?

Reading is my number one occupation in waiting rooms. Something riveting and escapist is best. If not, research for something I’m working on is also good.

Rule #2: Always bring a pen and notebook.

Because I’ll need to take notes on that research. Or, if not doing research, maybe I’ll have the presence of mind to work on my most recent project, or a blog piece.

Rule #3: Sleeping is an option.

No one cares if you fall asleep in a waiting room. Most people wish they could do the same. Snoring, however, is bad form.

Rule #4: Don’t hog.

If the waiting room is busy, use one chair.

Rule #5: The receptionist will let you use a bathroom, if you ask.

This comes in handy, especially if the wait is long.

Rule #6: You don’t have to carry a conversation.

People in waiting rooms tend not to be happy people. No one expects you to be conversational. Don’t be rude, of course, but if you’d rather not talk, an acknowledgment, small smile and return to your reading of choice usually is signal enough that you’d rather not talk.

Corollary: If you want to talk, you might not find welcome listeners.

Rule #7: Eat your lunch elsewhere.

Seriously. That’s why hospitals have cafeterias. Bad enough you have to wait. Worse is smelling someone’s meal while you're hungry. Worst is being sick and having to smell food that increases your nausea.

Rule #8: If you like to people watch, be discreet.

This is where listening is better than looking. But really. Is it any of your business?

Rule #9: It’ll smell funny.

There’s nothing you can do about it.

Rule #10: The wait will come to an end.

I find this especially useful to remember if I didn’t follow rules 1 and 2, and can’t sleep. There are just so many times I’ll want to read the posted notices. Magazines get boring. And I really, really, REALLY dislike the noise from TVs. But sitting back and working out a problem about a novel, daydreaming about what else I could be doing, or just relaxing is infinitely better than obsessively checking my watch and wondering, how much longer do I have to wait?

Published on June 13, 2012 09:57