Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 50

June 2, 2024

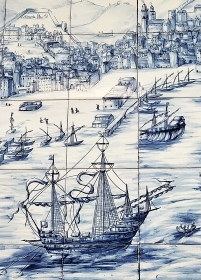

Portuguese tiling

June 1, 2024

The conqueror’s ruined castle in north Wales

THESE DAYS WE ARE so preoccupied with the Russian invasion of Ukraine that the English invasion of Wales is not in the forefront of our minds. In the 13th century, King Edward I of England (reigned 1272-1307) decided to conquer Wales. To do this, he built a series of castles from which his armies could enter Wales. One of these was built at Flint on the left bank of the River Dee not far from Chester, from which supplies could be easily carried either by land or by water (sea and river).

The castle at Flint was designed by Richard L’engenour and built between 1277 and 1278. Its form was based on Savoyard models. One of its circular towers was built larger than the others and separated from the rest of the castle – it served as the ‘donjon’ or keep.

Many of those who constructed the castle – English people – stayed on in the area to become the inhabitants of the new fortified, walled town of Flint. They felt safe within the town’s walls, but this sense of security was soon to be disturbed. For in 1294, the Welshman Madog ap Llywelyn led a revolt of the Welsh against their English rulers, and attacked Flint. Rather than letting the town fall into the hands of the Welsh, the Constable of Flint Castle ordered that the town be burned to the ground so that the Welsh rebels would be denied shelter and food.

The castle remained functional until the Civil War, when it, along with other strongholds, was destroyed following orders issued by Oliver Cromwell, soon after 1647.

Today, the impressive ruins are open to the public and well maintained by CADW, a Welsh Government body that looks after sites of historic interest. In 1838, JMW Turner created a watercolour painting showing the castle with a beautiful sunset behind it. We visited it on a rainy day in May 2024. Despite the inclement weather, seeing the castle gave us great pleasure.

May 31, 2024

Cotton and Abraham Lincoln and Mahatma Gandhi and Lancashire

LANCASHIRE USED TO be the centre of the cotton processing industry in the UK. Cotton grown in the southern USA and in India’s Gujarat was shipped to Lancashire, where the cotton mills used it to manufacture textiles.

In the heart of the city of Manchester, we were surprised to find a huge bronze statue of the former President of the USA, Abraham Lincoln (in office from 1861 to 1865). Lincoln played a significant role in the abolition of slavery in his country. Many of the slaves worked to grow and harvest cotton, much of which was sent to Lancashire. The processing of the cotton grown by the slaves provided employment for the workers of Lancashire. The statue was created by the American artist George Grey Barnard (1863-1938) in 1919, and is one of three castings – the others being in Louisville, Kentucky and in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Beneath the statue in Manchester and carved in the plinth, there is the wording of a letter sent by Lincoln to the working people of Manchester. Written on the 19th of January 1863, Lincoln thanked the workers of Manchester, who were supporting the abolition of slavery and at the same time suffering because of the blockade that prevented cotton reaching Lancashire from the southern states of the USA. According to one website (https://manchesterhistory.net/manchester/statues/lincoln.html), Lincoln’s blockade of the cotton exporting ports was not universally welcomed:

“To what degree the people of Lancashire gave this support willingly is questionable. Lincoln’s Union Army blockaded the southern ports preventing the Confederate supporters from trading their cotton and causing what was known as the Cotton Famine in the UK. By November 1862, three fifths of the labour force, 331,000 men and women, were idle. The British Government was encouraged to take action to overturn the blockade and riots broke out because of the hardship suffered by the workers. The Confederate Flag flew on some Lancashire mills.”

The American Civil War was not the only time that the Lancashire cotton workers had to suffer because of a freedom struggle taking place many thousands of miles away. In addition to the USA, British India was a supplier of cotton to the mills of Lancashire. Indian cotton was sent to Lancashire, and processed to make textiles that were then sold in India. Because of this, a vast number of weavers in India, who could have made the textiles, were made unemployed and impoverished.

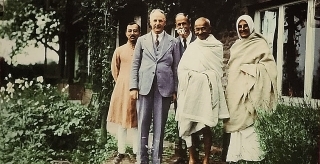

As part of Mahatma Gandhi’s attempt to free India from British rule, he initiated a boycott of cloth and clothing made with textiles manufactured in England. This was sufficiently successful to render a great number of Lancashire textile workers unemployed – at a time when the Great Depression was hitting the country. On the 25th of September 1931, Gandhi travelled from London to Darwen, a small town (with textile factories) north of Manchester. He spent the following days speaking to people of all walks of life, explaining the purpose of his Khadi movement – the boycotting of imported textiles and the encouraging of homespun Indian textile production. Both of my wife’s grandmothers chose to wear only khadi cloth because they supportrd the freedom struggle. James Hunt described Gandhi’s visit to Lancashire in his book “Gandhi in London”, and noted that:

“Everywhere Gandhi explained that whatever the effect of his khaddar movement and boycott might have on Lancashire’s unemployment was a result of his prior concern with the greater sufferings in India. While Britain had 3,000,000 unemployed. India had 300,000.000 villagers idle every year. The average Indian income was a tenth of what the British unemployed worker received from the dole …”

Overall, despite the effects that his boycott was having, the workers of Lancashire welcomed him warmly and supported his cause.

Until we visited the Manchester Museum, which is about 1.3 miles south of Lincoln’s statue, I was unaware of Gandhi’s visit to Lancashire. The museum has a gallery dedicated to the South Asian diaspora, despite being called “the South Asia Gallery”. One of its showcases concentrates on the Mahatma’s brief visit to Darwen.

We visited Manchester in May 2024 to see an art installation curated by our daughter. We also wandered around the city, sightseeing. Little did we expect to discover connections between this vibrant city and both Abraham Lincoln and Mahatma Gandhi.

May 30, 2024

An almost abandoned dock by the River Dee

WHEN I WAS A child, I had a jigsaw puzzle, whose pieces were shaped like the counties of England and Wales, as they were in the 1960s. When you put the pieces together correctly, you ended up with a map of England and Wales. The county of Flintshire always fascinated me because it was then divided into two separated parts. Today, the 27th of May 2024, we made our first ever visit to Flintshire. Amongst the places we looked at was Connahs Quay, which is on the Welsh bank of the River Dee.

In the early 18th century, the Dee silted up. This put an end to Chester being used as a port. Instead, Connahs Quay, which is close to the mouth of the Dee became an important port and a place where ships were built. The place was also an important fishing port. You can still see fishing vessels at Connahs Quay. We watched two of them setting out to catch shellfish as the tide came rushing furiously up the river.

The advent of the railway in the 19th century, brought industry and prosperity to the area, and the town grew. In recent years, industry has declined in the district, and Connahs Quay has lost its former prosperity. However, there is still a large power station nearby and the Shotton steelworks, now owned by the Tata company, provide some employment.

With a fine view of the recently constructed (1998), elegant suspension bridge over the mouth of the Dee and a promenade along the river Bank, Connahs Quay is a pleasant place to linger.

May 29, 2024

Maharajah and a dispute over fees at a tollgate

IN 1872 THE BELLE-VUE zoo in Manchester purchased an elephant from a travelling zoo in Scotland. The elephant was called Maharaja. It was decided to transport the creature by train from Edinburgh. Maharaja was not keen on that plan, and tore the roof off the railway wagon in which he was to travel.

It was decided to travel by road. Maharaja and his human companions walked from Scotland to Manchester. Many tales have been told about this journey. One of them relates that when the party reached a certain tollgate, there was a dispute about the amount that needed to be paid to allow an elephant through the gate. It is said that while the keepers were discussing the matter with the man at the tollgate, Maharaja solved the problem by using his trunk to open the gate.

This tale, which might or might not be true, has been illustrated in a painting that hangs in the Manchester Museum. Entitled “The Disputed Toll”, it was painted in 1875 by Heywood Hardy.

Maharaja lived at Belle-vue zoo for 10 years before succumbing to a fatal illness. He was then about 18 years old. This is a young age – many elephants live for more than 40 years. Maharajah’s skeleton now stands alongside Hardy’s painting in the entrance hall of the museum.

May 28, 2024

An artist from Vienna who lived in Hampstead (north London)

HAMPSTEAD HAS BEEN home to many artists – both painters and sculptors. Some of these are well-known, such as John Constable, George Romney, Stanley Spencer, Henry Moore, and Barbara Hepworth – to name but a few. Others are less widely known. Amongst the lesser-known is the late Marie-Louise von Motesiczky (1906-1996), some of whose paintings are on display in a special exhibition in Hampstead’s Burgh House until the 15th of December 2024. In addition to the works in the temporary exhibition, Burgh House’s permanent collection includes a few of her paintings.

Marie-Louise was born in Vienna (see: www.motesiczky.org/biography/). Her mother’s family were well-connected with Vienna’s flourishing intellectual circles in the early 20th century. Her grandmother, Anna Von Lieben, was one of Freud’s first psychoanalytical patients. At the age of 13, Marie-Louise left school, and began studying art in Vienna, The Hague, Frankfurt, Paris, and Berlin. In 1927, she joined the master classes held by the artist Max Beckmann (1884-1950) in Frankfurt-am-Main. This painter became an important influence in her life and work.

After the Anschluss (the Nazi annexation of Austria) in March 1938, Marie-Louise and her mother, Henriette, left Vienna. They went to Holland, where, in 1939, Marie-Louise had her first solo exhibition. Soon after this, she and her mother left for England, and settled in Amersham. There, she met the Bulgarian writer Elias Canetti (1905-1994) and his wife. Canetti was to become an extremely close friend of Marie-Louise. At Burgh House, we saw her portrait of him on display.

When WW2 was over, Marie-Louise and her mother moved into a flat in West Hampstead, which they rented until 1960. Then, they purchased a large house in Hampstead, number 6 Chesterford Gardens (a short road linking Frognal and Redington Road). While living there, she painted many portraits of her ageing mother. Some of these were on display at Burgh House.

Marie-Louise is now highly acclaimed as a 20th century artist in the country where she was born. Although the paintings I saw today at Burgh House are often imaginative and pleasant enough, I began to understand why she has not become as well-known as some of the many other artists who lived in Hampstead. However, everyone has different tastes in art. So, a good way to judge this artist’s work would be to pay a visit to Hampstead’s lovely early 18th century Burgh House.

May 27, 2024

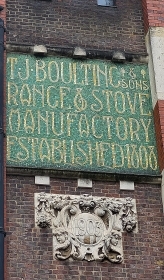

The writing on the wall

It’s on the wall

In small tiles so clearly written

So we won’t forget

The notice is on a building in Riding House Street, London

May 26, 2024

Women with many heads on canvases at an art gallery in central London

TODAY, WE VIEWED an exhibition of paintings by an artist born in India, who spent most of her life in the British Isles. The artist is Gurminder Sikand (1960-2021), who was born in Jamshedpur, but moved to the Rhondda Valley in South Wales with her parents in 1970. Her artistic training was first at the Cardiff College of Art and Design (in 1979-80) and then at the City of Birmingham Polytechnic (now Birmingham City University), where she was awarded a fine art degree. In 1983, she and her husband moved to Nottingham. Her work began to attract wide attention after one of her pieces was selected as the winner of the East Midlands Art Prize by the South African artist Gavin Jantjes.

In an obituary written by her husband, published in thegauardian.com on the 14th of February 2022, it was noted that her work:

“… was characterised by images of strong women. This was true of her many self-portraits, her paintings influenced by Indian folk art, her watercolours of women hugging trees (inspired by the Chipko anti-deforestation movement), and latterly her drawings of muscular female figures whose physiques reflected Gurminder’s workouts at her city-centre gym in Nottingham.”

The paintings we saw today (22nd of May 2024) at the Maximillian William gallery in London’s Fitzrovia were some of Gurminder’s earlier works, created between 1986 and 1992. Most of the 19 works include depictions of women. All of them are slightly mysterious, but also eye-catching. Many of them include women with several heads. I wondered whether in creating these she was thinking about Hindu deities that are often shown as having many arms. As far as I am aware few, if any, Hindu deities are shown in images as having more than one head, but seeing Gurminder’s women with many heads made me think about the multi-limbed deities in Hindu imagery.

Trees also figure prominently in many of the paintings we saw. Regarding this and her painting style, the gallery’s press release has this to say:

“Images of women drawn from Indian mythology recur throughout Sikand’s work. Her interest in the figure of the goddess – particularly the Hindu goddess Kali, who both destroys and creates the world anew, and is often pictured with a garland of human heads – is evident in her depictions of women metamorphosing into nature. In Sikand’s paintings, women are seeds buried in soil, hang on tree branches to provide shelter, or are even the earth and sky themselves. These amorphous relationships between the figure and nature were further inspired by the Chipko environmental movement, which began in north India during the 1970s, when villagers – mostly women – embraced trees at risk of deforestation, a protest that also highlighted their primary role as caregivers. Sikand’s female figures are often portrayed as strong: appearing resolute with multiple heads or acting as protectors over her landscapes.”

Although Gurminder left India when she was only 10 years old, and was then immersed in British life, culture, and education, her Indian heritage never deserted her, and is expressed in her wonderful paintings. I enjoyed viewing this well-displayed exhibition, and I recommend seeing it before it ends on the 29th of June 2024.

May 25, 2024

Modernist architecture on a popular shopping street in central London

AT GROUND LEVEL, London’s Oxford Street is lined with numerous retail outlets, many of which can be seen on shopping streets and in malls all over England. Raise your eyes above ground level, and you will notice that the shops are beneath buildings designed in a bewilderingly wide range of styles. Today (the 22nd of May 2024), I spotted a Modernist style building, number 219 Oxford Street, which is on the corner of Oxford Street and Hill Street. Its ground floor has become part of a Zara shop’s showroom.

The upper floors of the five-storeyed number 219 retain their 20th century Modernist style architectural features, and its Oxford Street facade is adorned with three bas-relief plaques. One of them, at the fourth-floor level bears the date ‘1951’ and a logo. Despite its date, the building has remarkably clean lines and an elegant simplicity. There is much information on the Internet about this edifice, but even though I have walked past it many times, it was only today that it caught my attention.

The Historic England website (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1352668?section=official-list-entry) revealed that the building:

“… was designed by Ronald Ward and Partners in 1950 for the landlord Jack Salmon, who took the second-floor suite for himself. The scheme was revised in February 1951, but was not built until after August 1951 (explaining the plaques celebrating the Festival of Britain – an event which was held in the summer of that year), and appears not to have been completed until 1952, as evidenced by the dated tile near the door to the upper floors. Despite the delay in its construction the building was among the very earliest post-war commercial buildings to be put up in the capital.”

Another website (https://lookup.london/219-oxford-street-history/) provided some detail about what is depicted on the plaques. The plaque with the date 1951 also contains the (1951) Festival of Britain logo. Above this, the top plaque shows the Royal Festival Hall and next to it the Shot Tower from Lambeth Lead Works, which stood close to the Hall, but was demolished in 1962 to make way for the Queen Elizabeth Hall. The lowest plaque depicts the Skylon, which was also part of the Festival of Britain complex of structures (on the South Bank), but no longer exists.

Number 219 was threatened with demolition in 2004, but luckily for us it escaped this fate, and is now protected as a Grade II Listed Building.

May 24, 2024

Houses in England built with money made in India

DURING A VISIT TO Basildon Park near Reading, I spotted a display of photographs of “Nabob houses in the Indian Style”. A ‘nabob’ was someone who was conspicuously rich, having made his fortune in India. These were buildings constructed by people who had made their fortunes while working in India. for the British East India Company. Some, but not all of these, buildings incorporate architectural features derived from the architectural styles that the British found when they visited India.

Late 18th century Basildon Park, which was built by a Brit who had made his money in India, is a Nabob’s house, but without any features borrowed from the Indian subcontinent. It is a Palladian-style building. It was one of about 30 houses built in Berkshire for the nouveau-riche British ‘nabobs’, who had enriched themselves in India.