Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 49

June 11, 2024

A teacher at school and a painting at Sotheby’s auction house

This painting on display at Sotheby’s in New Bond Street was created by Sir John Kyffin Williams (1918-2006). He was born in Wales on the island of Anglesey.

When I was a pupil at London’s Highgate School (between 1965 and 1970), Kyffin Williams taught art at the school. He was the senior art master between 1944 and 1973. I was fortunate to have attended a few of the painting sessions He supervised.

In 1968, Kyffin visited the Welsh settlement in Patagonia. After his return to England, he gave a fascinating talk about his trip to us at the school. I attended this, and still remember some if what he related.

A few years ago, we drive to Anglesey to see his work at the Oriel Mon gallery near his birthplace, Llangefni.

Seeing this painting at Sotheby’s brought back happy memories.

June 10, 2024

No longer can you travel overland from this station to Leipzig or Marseilles

THE FIRST BLACKFRIARS railway station was opened in 1886. This station has been replaced by a 21st century station that now serves trains of the Thameslink network, which connects places north of London with places south of the city – no further north than Peterborough, and no further south than Brighton. Originally, when it first began serving passengers in the 19th century, trains carried people to overseas destinations including Leipzig, Naples, St Petersburg, and Marseilles.

The ticket hall of the current Blackfriars Thameslink station contains a reminder of the days when passengers departed for places much further afield than Brighton and Peterborough. It is a section of the original station’s facade, on which a list of destinations once reachable from the station is inscribed . The list includes many places on the European mainland as well as places in southeast London and Kent, through which travellers heading towards foreign lands had to pass.

I do not recall the old Blackfriars station, but the current one is an elegant example of modern architecture. What is particularly nice is that the platforms are on a bridge spanning the Thames. While waiting for a train, passengers can enjoy splendid views up and down the river.

June 9, 2024

A deserted abbey in ruins close to the River Dee in North Wales

WE USED TO make long trips by car in France. Amongst the many sights we visited were various Cistercian abbeys, such as those at Citeaux and Clairvaux. Later, during trips to Wales, we often visited the ruins of the Cistercian Abbeys at Strata Florida and at Tintern on the River Wye. I do not know what drew us to these Cistercian places, but we went out of our way to see them. So, when we were staying near Warrington in Lancashire and I noticed that we were not far from yet another Cistercian site, we made a bee line for it. Overlooking the River Dee, the ruins of Basingwerk Abbey are located near the town of Flint in the county of Flint.

Though not as extensive as the ruins at Tintern, there is plenty to see at Basingwerk. Dedicated to the Virgin Mary, the abbey was founded in 1132 by Ranulf de Gernon, 4th Earl of Chester. Being on the border between England and Wales:

“Basingwerk was patronised by both the Welsh and Anglo-Norman nobility. Royal benefactors included Henry II, Prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth (d. 1240), Prince Dafydd ap Llywelyn (d. 1246) and Edward I.” (https://www.monasticwales.org/browsedb.php?func=showsite&siteID=24).

Originally founded as part of the Order of Savigny, it joined the Cistercian Order in 1147. In about 1355, it was reported that the abbey was in a devastated condition. During the early 15th century, Basingwerk tried to encourage pilgrims to visit its shrine, hoping that this would raise funds to repair the place. Between 1481 and 1522, Abbot Thomas Pennant restored the abbey and improved its fortunes. Sadly, by 1537, the institution had been suppressed by order of King Henry VIII. In 1540, the site of the former monastery was sold. After changing hands a couple of times, it became the property of the Mostyns of Talacre.

In 1923, the ruins of the abbey were taken over by the government, and now they are well-maintained by CADW – the historic environment service of the Welsh Government. Despite the appallingly bad weather prevailing when we visited the remains of the Cistercian abbey, we were able to enjoy wandering around the ruins. To recover from the inclement conditions, we took refreshments in the nearby café/restaurant in Basingwerk House.

June 8, 2024

A small but important relic on an island in Essex

THE AVAILABILITY OF water is essential for human life. Since 8400 BC, or even earlier, mankind has been digging wells to access sources of groundwater. In England today, usable wells are few and far between because water is supplied by various other means. Occasionally, one comes across wellheads of now disused wells. One of these has become a minor visitors’ attraction on the lovely small island of Mersea, which is south of Colchester on the north side of the mouth of the Blackwater River.

The well head, which in in West Mersea and has been recently restored looks like a square wooden crate. It has a commemorative bronze plate on its square covering. Known as St Peter’s Well, it was an important source of water from ancient times until the early 20th century. It may have been associated for a while with a West Mersea Priory (founded 1046, dissolved 1542) that once stood nearby.

In April 1884, Mersea Island was struck by an earthquake. A crack in the ground opened near St Peters Well, and for a short time the water in it:

“… turned white, as if mixed with lime, and was quite warm, but the day after had resumed its pellucid qualities.” (www.merseamuseum.org.uk/mmphoto.php?pid=SS050030&hit=631&tot=642&typ=cat&syn=all)

Today, there is little to see but the restored wooden wellhead that stands on a slope overlooking the wide sandy beach, which appears when the tide is out, The metal plate contains quotations from the Bible and the information that the well, which had served the people for over 1000 years, was one of the main sources of fresh water for the islanders, and had never run dry.

Judging from the contents of rubbish bins awaiting collection from the street entrances of houses in West Mersea, an important source of fluid intake is nowadays bottles and cans obtained from the booze shelves of off-licenses and supermarkets.

June 7, 2024

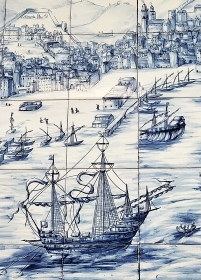

Sailing boats at rest

June 6, 2024

A Nigerian artist near London’s Edgware Road

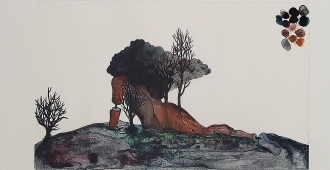

OTOBONG NKANGA WAS born in Kano (Nigeria) in 1974. Her artistic training was carried out in Ile Ife (Nigeria), then in Paris (France). Now, she lives and works in Antwerp (Belgium). I doubt that I would have come across her work had we not visited the Lisson Gallery near London’s Edgware Road, where some of her artworks are on display until the 3rd of August 2024.

The exhibition contains sculptures, two attractive tapestries, and several framed works on paper. The sculptures, which are pleasant enough, are made with materials including clay, glass, and fibres. A leaflet with a text written by the artist describes how she is portraying her connections with nature. Without this text, I would have been hard pressed to realise what she described.

What impressed me most in the exhibition were Nkanga’s delicately executed framed works on paper. These, more than the other exhibits, convinced me that she is a highly talented artist. As I compared them to the sculptural works, I was remined of my thoughts about the artist Damien Hirst. At first, I thought that his works were interesting although often gimmicky, and did not display his deepest artistic feelings. I changed my mind about his inherent talents when, some years ago, I saw an exhibition of his paintings at the White Cube Gallery in Bermondsey. Great artists like Picasso and David Hockney, who are known for their experimental exploration of artistic expression, were, in their younger days, highly skilled exponents of what might be considered ‘traditional’ composition style. This was what I felt about the framed works on paper by Nkanga – although she clearly enjoys experimenting with a variety of media (including with recorded sounds – a soundscape, which is included in the exhibition), she is clearly able to express herself beautifully in the traditional art of sketching and painting.

Had we enough wall space and sufficient spare cash, I would have happily bought several of Nkanga’s lovely works on paper.

June 5, 2024

No arms and legs but she was a competent painter of portraits

THE EXHIBITION WE saw today (the 3rd of June 2024) at London’s Tate Britain exceeded our expectations. Called “Now You See Us”, it consists of about 150 artworks created by over 100 women, working between the years 1520 and 1920. Apart from their gender, these artists shared at least one other thing in common: they were professional artists who worked in Britain, rather than talented amateurs. The earliest works on display are by women working in the Tudor Courts during the 16th century. They include Susanna Horenbout (1503–1554) and Levina Teerlinc (c.1510s–1576), some of whose exquisite paintings can be seen in the exhibition.

There were too many artists to be able to describe them all in this short essay. Some of them (for example: Angelica Kauffman, Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Beale, Mary Moser, Laura Knight, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Elizabeth Forbes) are now well-known, but others whose works are exhibited are somewhat obscure. One notable artist, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), who lived (and painted a little) in England for about three years, is not exhibited in the show, which is a pity because from what I have seen of her work (at Ickworth House in Suffolk), she was a highly competent artist. Next, I will highlight several things that particularly interested me in this superb exhibition.

There are several small paintings created on sheets of ivory. They reminded me of the glass paintings I have seen in India. One of these is a beautifully executed self-portrait by Sarah Biffin (1784-1850). She was born without arms or legs, yet learned to sew, write, and paint using her mouth. Early in her career, she worked at country fairs, where people used to pay to watch her draw and paint. Later, she established herself as a professional portraitist.

There were three photographs by the Victorian photographer, Julia Margaret Cameron, about whom I have written a short book. I am glad that her works are included in the exhibition because her skill was creating painterly works of art, rather than accurate images, with photography. Here work was greatly admired by the pre-Raphaelites.

I was interested to see a painting by Frances Reynolds (1729-1807), who was the sister of the famous artist Sir Joshua Reynolds. Although the painting is not a great work of art, its presence in the exhibition exemplifies the situation for women artists before they were first admitted to art schools in the second half of the 18th century. Before that time, several of the artists, whose work is on display, had to learn to paint from male artists in their family – fathers, husbands, and so on.

For a very personal reason, I was interested to see a painting by the poet and painter Anne Killigrew (1660-1685). Her father was the playwright Henry Killigrew (1613-1700). The reason that this Killigrew family is of interest to me is that their coat of arms includes the double-headed eagle, indicating the family’s connection with the mediaeval Earls of Cornwall. Sadly, Anne, whose works are attractive, died young following a smallpox infection.

One room of the exhibition contained works by women artists working in the Victorian era. These, often sentimental, works did not appeal to me. However, the final room, which contains works created in the first two decades of the 20th century, is spectacular. Many of the exhibits in this room demonstrate how artists were abandoning tradition, and exploring new techniques. This period coincided with the gradual improvement in women’s rights in Britain.

The exhibition continues until the 13th of October 2024, and is well worth visiting.

June 4, 2024

Sister Lizzie in a street in London’s Hammersmith

MACBETH STREET IS a short thoroughfare in Hammersmith. It runs from Kings Street to the A4 dual carriageway. We often walk along it to reach the pedestrian subway beneath the busy A4. There is an architecturally unexciting building on Macbeth Street, which I would not have stopped to look at had I not noticed two memorial plaques affixed to it.

One of the plaques bears the words:

“This stone was laid To the Glory of God on June 28th 1930 on behalf of the South Street Mission by Mrs Alfred Goodman. Mission superintendent Sister Lizzie”

The other plaque reads:

“To the Glory of God on June 28th 1930 on behalf of the Shaftesbury Society by Sir Charles JO Sanders KBE. Treasurer L(?) Goodman Esq”

The South Street Mission was founded in 1901 by Sister Lizzie, who died in 1949. In 1909, the South Street Mission brass band was formed, and was active until the mid-1950s. According to a website about streets in Hammersmith (https://edithsstreets.blogspot.com/2016/11/riverside-north-of-river-and-west-of.html):

“South Street Mission Hall. This was run by Sister Lizzie as a women’s refuge. South Street Mission Brass Band was active from around 1910s through to the 1950s. The building now appears to be operated as a church centre probably through St.Paul’s church. It also appears to have links with the Shaftesbury Society and the St.Barnabas movement operating as a centre for the homeless and a night shelter for street sleepers.”

As for the Shaftesbury Society, according to Wikipedia:

“In 1872 the social reformer Lord Shaftesbury established the Emily Loan Fund to enable young women flower sellers to support themselves. Later, in 1914, the Ragged School Union merged into the Shaftesbury Society, becoming fully subsumed under the title of the Shaftesbury Society in 1944.”

“Whos Who 1938” has an entry for Sir Charles JO Sanders. He was an important civil servant involved in shipbuilding matters. The reference to him includes his philanthropic work:

“… a well known worker amongst the poor in all kinds of religious, social, and philanthropic work, Chairman of Council of Shaftesbury Society and Ragged School Union, 1918, 1919,1929, 1930, 1936 and 1937, Treasurer since 1933.”

As for Sister Lizzie, I have not been able to discover more about her.

Today, the building is used by various religious groups including the ‘House of Worship’ and the ‘Sword of the Spirit – Int. Prophetic Ministries’.

I guess that the memorial plaques, which caught my eye, were placed when the present building was built to replace an earlier version.

June 3, 2024

Son of missionaries at the Camden Art Centre in Hampstead

MATTHEW KRISHANU WAS born in Bradford (UK) in 1980. His parents were Christian missionaries. His father was British, and his mother Indian. Their work took them to Bangladesh, where Matthew and his brother spent some of their childhood years. Matthew’s formal education in art took place at Exeter University, and then at London’s Central St Martin. Today, the 1st of June 2024, we viewed a superb exhibition of his paintings at the Camden Art Centre in Hampstead’s Arkwright Road. The exhibition continues until the 23rd of June 2024.

Many of the paintings on display include depictions of two young boys – the artist and his brother – often in a tropical setting that brings to mind places on the Indian Subcontinent. The paintings vary in size, but all of them are both pleasing to the eye and full of interest. His paintings of trees and other plants are impressionistic. Like many of the other pictures, they were inspired by the artist’s childhood in Bangladesh and later visits to India.

One room with several paintings contains works that must have been inspired by the artist’s memories of being brought up in a missionary family. The paintings in this gallery are depictions of the colonial legacy of Christianity in the Indian Subcontinent. Another indication of the artist’s upbringing in a Christian religious family setting is the appearance of small images of the Last Supper in several of the paintings, including those which are not specifically portrayals of religious environments.

Although, there is no doubt much that can be read into his paintings, Krishanu’s works are both approachable and engaging. I liked them immediately – as soon as I saw them. It is worth a visit to Arkwright Road to see this well laid-out exhibition.