Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 165

April 9, 2021

Beat the enemy

April 8, 2021

A Venezuelan in London

KARL MARX, MAHATMA GANDHI, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Ho Chi Minh, Benjamin Franklin, Simon Bolivar, Giuseppe Mazzini, and many other figures, who have caused major changes either in their own countries or in the wider world, have spent time living in London. Now I will introduce you to yet another man who lived in London and is celebrated as a liberator of the country in which he was born.

Despite having spent twelve years studying at University College London, I have not bothered to explore nearby Fitzroy Square until this year, 2021. The only part that I knew about while I was at college was the Indian YMCA, located in a building that was built the 1950s, where one can still enjoy Indian cuisine at below average prices. I shall write about this establishment in the future, as I will about Fitzroy Square. But now I will concentrate on a person, whose statue stands at the south east corner of the square, facing the Indian YMCA at the north end of Fitzroy Street.

Francisco Miranda

Francisco MirandaThe statue, dressed in 18th century attire, depicts Francisco de Miranda (1750-1816), standing with his left leg forward and a scroll in his right hand. Bare headed, his left hand is over his chest above his heart. Born in Caracas in the Venezuela Province of the Spanish colony of New Grenada, his full name was Sebastián Francisco de Miranda y Rodríguez de Espinoza. He was born into a wealthy family and educated at the best schools. Following a clash between his father and the aristocratic elite, Francisco travelled to Spain in 1771. Francisco studied in Madrid and in 1773 his father bought him a captaincy in the Spanish Army. He took part in military actions in North Africa, but his superiors considered that he devoted too much of his attention to reading and was also involved in various abuses of authority (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_de_Miranda).

Miranda was next sent to the Americas and was involved with the Spanish in the American War of Independence. In 1782, he was involved in the Capture of the Bahamas. His superior, Galvez, was upset that this had begun without his permission and arrested Miranda. It might have been this clash with Spanish officialdom that made Miranda begin to consider being involved in the quest for independence of the Spanish colonies in Latin America. With his involvement in the failure of the Spanish invasion of Jamaica in about 1782, the Spanish authorities wanted to arrest Miranda and take him to Spain. Fearing that he would not be tried fairly, he fled to the British colonies in North America in July 1783. In what was to become the USA, he met with, and became acquainted with the ideas of, leaders of the American independence struggle, such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Samuel Adams.

Between 1785 and 1780, Miranda stayed in Europe, first landing in London in February 1785. In London, the Spanish authorities kept a close watch on him. Between 1802 and 1810, he lived near to Fitzroy Square at number 58 Grafton Way, to which a commemorative plaque is attached. The building is next door to the current home of the Consulate of Venezuela (“Republica Bolivariana de Venezuela”). It was in number 58 that Miranda met the great liberator of Latin America, Simon Bolivar (1783-1830) in 1810. It was also in 1810 that the Venezuelan patriot, philologist, jurist, and poet, Andres Bello (1781-1865) lived in this house. Bello had arrived in England with Bolivar as part of an expedition to raise funds for revolutionary activities in Latin America.

Miranda travelled around Europe and took an active part in the French Revolution between 1791 and 1798, when, disillusioned with the revolutionary movement, he returned to London. Back in London, at Grafton Street, Miranda had two children, Leandro (1803-1886) and Francisco (1806-1831). Their mother was his housekeeper Sarah Andrews, who became his wife.

From 1804 onwards, Miranda became actively involved with freedom struggles against the Spanish in the Caribbean and in what was to become Venezuela. He returned to Venezuela, along with Bello and Bolivar, when the First Venezuelan Republic was proclaimed in April 1810. It was short-lived. Miranda, who was briefly Dictator of Venezuela, was arrested, along with Bolivar, by the Spanish in mid-1812. Bolivar was released, but Miranda was shipped to Spain, where he died in prison in Cadiz in 1816.

Miranda’s statue next to Fitzroy Square was erected in 1990. It is a copy of one made by the Venezuelan sculptor Rafael de la Cova (c1850-c1896) in 1895 (www.londonremembers.com/memorials/francisco-de-miranda-statue). As the statue was erected in 1990, eight years after I finally completed my studies at University College and I had not been near Fitzroy Square since 1982, it was hardly surprising that it was only this year that I first saw it, one of several statues depicting liberators of Latin America, which are dotted around in London.

April 7, 2021

Three pubs and a hero

LESS THAN 580 FEET long, Rathbone Street runs parallel to part of London’s Charlotte Street. Short though it is, it is not lacking in interest. The quiet thoroughfare was originally named ‘Glanville Street’, before being renamed Upper Rathbone Place, and then its present name (www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol21/pt3/p12). Rathbone after whom Rathbone Place and Street were named was a carpenter and builder, Thomas Rathbone (died 1722), who lived in a house on the Place around 1684. Rathbone Street was laid out 1764-65 (www.ucl.ac.uk/bartlett/architecture/sites/bartlett/files/chapter31_hanway_street_and_rathbone_place.pdf). During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Rathbone Street was occupied by various artists including the sculptor M Bordier and the painter John Rubens Smith. Today, various vestiges of the past can be seen on the short street.

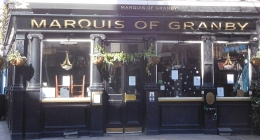

The Marquis of Granby pub at the southern end of Rathbone Street was named in honour of Lieutenant-General John Manners, Marquess of Granby (1721-1770), who fought heroically at the Battle of Warburg (1760) during The Seven Years War (1756-1763). He became Commander of the British Army in 1766. There are many pubs named after him because, it is said, he set up many of his soldiers as publicans when they retired from military service. The pub bears old boundary markers marking the demarcation line between the parishes of St Pancras and St Marylebone. The pub now stands in both the Boroughs of Camden and Westminster. In the past, the pub’s customers have included Dylan Thomas and TS Eliot. The building housing the pub was already built by 1765.

There are two other pubs in Rathbone Street. One of them halfway along it is The Newman Arms, another haunt of Dylan Thomas and also frequented by George Orwell. Established in the 1730s, this pub features in two of Orwell’s novels: “1984” and “Keep the Aspidistra Flying”. Once upon a time, the pub was a brothel. A painting depicting a prostitute in period costume covers a bricked in upper storey window. Across the road from the pub there is a plaque on a building that bears the words: “Hearts of Oak Benefit Society” and the date 1888. This marked the rear entrance to the offices of the Society. Its main entrance was 15-17 Charlotte Street (www.londonremembers.com/memorials/hea...). At the north end of the street, there is a third pub, The Duke of York. Bearing the date 1791, it was where the author Anthony Burgess was drinking when he witnessed an attack by a gang bearing razors (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Duke_of_York,_Fitzrovia). The pub’s sign bears a portrait of someone who is far younger than the pub, the current Prince Andrew. This pub is the only one with the name The Duke of York which has a pub sign depicting the current Duke of York. The pub was originally named to honour an earlier Duke of York.

Rathbone Street, short as it is, contains three pubs. Its continuation southwards towards Oxford Street, Rathbone Place, contains two pubs and another drinking place, once a pub but now named The Liquorette, in a stretch of road even shorter than Rathbone Street. Thus, there used to be 6 pubs within a stretch of roadway 364 yards in length.

Returning to the south end of Rathbone Street, its southwestern corner, we reach what first got me interested in this short lane. During WW2, there was a London Auxiliary Fire Station, Sub Fire Station 72Z, on this spot. During the night of the 17th of September 1940, it was hit by a bomb dropped by the German Luftwaffe. The building burst into flames. Seven firemen lost their lives. However, two men were saved by the brave actions of Fireman Harry Errington, who was later awarded a George Cross to recognise his bravery. He rescued two of his comrades from the flaming ruins. Harry Errington (formerly ‘Ehrengott’) was son of Jewish immigrants living in Soho. Harry, son of Baila and Shepsel Ehrengott who arrived in London from Poland in 1908, was born in Soho in 1910 (https://british-jewry.org.uk/New%20Member%20Area/BJ%20News/100806/Microsoft%20Word-B-JNews8final.pdf).

After training to become an engraver, he had to abandon this because his lungs became affected by nitric acid fumes. Then, he joined a relative, a tailor in the Savile Row firm of Errington and Whyte. He became a master tailor. Then, WW2 broke out. Mike Joseph wrote in the “B-J News” of August 2006:

“It was in 1940 that Harry earned true celebrity status. Having joined the Auxiliary Fire Service at the outbreak of the Second World War a year earlier, he was one of several firemen on duty in a basement rest-room during an air raid, when the building collapsed. An enemy bomb had scored a direct hit, and twenty people died, including six firemen; Harry was lucky: he was only knocked out! When he came round, the building was on fire. He could have escaped with little difficulty, but two of his comrades were trapped under rubble: how could he leave them? He wrapped a blanket round his head against the flames and, digging with his bare hands, managed to free one of the men. He dragged him to safety, upstairs into the street, and then, although he was already badly burned, went back and rescued the other man.”

Harry was true to the words quoted from the Book of Joshua, which are written on one of the two commemorative plaques marking the former fire station in Rathbone Street:

“Be strong and of good courage.”

Harry returned to tailoring when the War was over but remained in touch with the London Fire Brigade. When he died in 2004, he was the last surviving Jewish holder of the George Cross.

Though less lively than nearby Charlotte Street in ‘normal’ times, Rathbone Street is worth a detour, if only to quench your thirst in one of its three pubs. I wonder whether Harry Ehrengott and his colleagues made use of any of these drinking holes during the odd quiet moments between their brave firefighting tasks.

April 6, 2021

Life begins again

April 5, 2021

A small village near Cambridge

THE TINY VILLAGE of Madingley is just under 3 ½ miles west of Kings College Chapel in Cambridge, yet it feels a long way from anywhere. The settlement was recorded as ‘Matingeleia’ in about 1080, as ‘Mading(e)lei’ in the Domesday Book, and ‘Maddingelea’ in 1193. The name means ‘the leah of Mada’s people’, a ‘leah’ being a glade where mowing was done, in other words, a clearing. What became of Mada and his or her people, I have no idea. In 1086, there were 28 peasants in Madingley but by 1279, there were 90 people in the village (www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/cambs/vol9/pp165-166). The population in the 18th century reached about 150 and increased to over 200 in the 19th century. In 2011, there were 210 people living in the civil parish of Madingley (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madingley). Whenever I have visited the village, where my cousin lives, I have never seen many people out and about.

The earliest record of a church in Madingley was in 1092. Much of the present, attractive church (St Mary Magdalene), which was closed when we last visited, contains structures that date back to the 13th and 14th centuries (www.madingleychurch.org/history/). The building has a square tower topped with a tall steeple. The north side of the exterior of the nave of the church is brickwork made of irregularly shaped and equally irregularly arranged stones and mortar. The south side looks plain because the stonework is covered with plaster rendering. A church official who was passing by while I was taking photographs explained that the rendering, which protects the wall from penetration of rainfall, is probably original and that the church authorities are currently trying to decide whether to cover the north side with rendering.

The church stands next to the entrance to the grounds of Madingley Hall. A long drive climbs sinuously up a slope to the hall, whose construction was begun by Sir John Hynde (died 1550) who acquired the Madingley estate in 1543 (https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1000627). Hynde, who had studied at Cambridge University, was an important judge. He was called to the Bar at Grays Inn and became Recorder of Cambridge in 1520. In 1539, as a result of the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536-1541) ordered by King Henry VIII, he was granted the Cambridgeshire estate now known as Anglesey Abbey and in 1542-43, he came to possess lands at Madingley (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Hynde). The construction of the Hall was continued by John’s son, Sir Francis Hynde (c1532-1596). In 1756, Sir John Hynde-Cotton, employed Lancelot (‘Capability’) Brown (1716-1783) to landscape the Hall’s grounds. I do not know how much of the landscaping seen today was that created by Brown but the lovely pond at the bottom of the lawns sweeping down from the front of the house looks like one of his typical features. The property remained in the Hynde family until 1858. A descendant of the family, Maria Cotton, married Sir Richard King, who obtained the part of the estate that included the Hall. In 1861, Maria rented the Hall to Queen Victoria for use by the Prince of Wales, the future Edward VII, whilst he studied at Trinity College, Cambridge University. Currently, the Hall is home to the University’s Institute of Continuing Education and has sleeping accommodation both for those attending courses and also for visitors to the area.

In 1871, the Hall was sold to Mr Hurrell and then later to Colonel Walter Harding, who completely renovated the Hall. His heirs sold it to the University of Cambridge in 1948 (www.madingleyhall.co.uk/). Harding’s granddaughter Rosamund gave 30 acres of land on which the American Military Cemetery now stands beside the village of Madingley. The graves in this cemetery, mostly Christian and a few Jewish, are arranged neatly with military precision.

A half-timbered thatched lodge stands by the entrance to the drive next to the church. The former was built in about 1908 by Colonel Harding. The driveway crosses a bridge at one end of the lake or pond. This fake bridge was one of Lancelot Browns landscaping features. Sadly, when we last visited, most of the Hall was covered with scaffolding. Despite that, we were able to admire the mainly 16th century architecture of the building. One particularly interesting feature is the ogival gothic archway that leads into a courtyard behind the original Hall. Decorated with heraldic and other mouldings, this brick and limestone archway was originally part of the Old Schools in Cambridge. Sir John Hynde-Cotton brought the archway to Madingley Hall in 1758. It is worth passing beneath the archway, which bears the date ‘1758’, and entering the walled kitchen garden on the left of it. This area contains a lovely variety of well-tended plants and shrubs.

Tiny Madingley, dwarfed by the Hall and its gardens, has one pub, the Three Horseshoes. It has been in existence since 1765, if not before. Attractively thatched, as is the village hall nearby, the pub we see today was built in 1975, following destruction of an earlier building by fire. I have eaten at the pub once. My impression was that it is a place to which most of its customers drive from elsewhere. It is more of a restaurant than a typical pub. I am curious to know how many of the villagers use it to enjoy a pint or two. On our recent visit in April 2021, the establishment looked sad, being closed on account of the covid19 lockdown.

Peaceful Madingley is home to a private nursery school, housed in a building dated 1844 as well as a discreet complex of University of Cambridge animal behaviour laboratories. Apart from these attractions, there is a disused telephone box that now serves as a library where anyone can take books for free so long as they replace them with others. It is a pity that there is no village shop, often a focus of village life, but given the small population of the place, maybe its absence is not surprising.

Little Madingley is now a suburb of Cambridge yet it has not merged with the city physically. It remains at heart a picturesque and charming example of ‘village England’ – a place to take refuge from the stresses and strains of modern life.

April 4, 2021

He criticised Charles Darwin

IT AMAZES ME that one can walk along the same route many times and miss features that turn out to be fascinating. I do not know how many times we have walked past Leinster Square near Bayswater and missed seeing a small information plaque attached to the cast-iron railings that keep the public out of the lovely private Leinster Square Gardens. Today, the 1st of April 2021, we saw it for the first time. Apart from providing a short history of this London square, it also mentions a person, about whom I have been curious for a while, since seeing a memorial to him near Portobello Road during our first covid19 ‘lockdown’.

Leinster Square was laid out by a property developer, George Wyatt, between 1856 and 1864 on land that was once used for market gardening and plant nurseries (http://www.lsga.org.uk/LSGA_Histories.html#:~:text=Building%20began%20in%201856%20and,character%20soon%20grew%20rather%20mixed.) The first inhabitants of the square were wealthy but soon the square became surrounded by hotels, flats, and lodging houses. Since then, this has remained the case. The buildings surround a beautifully maintained private garden, accessible mainly to people living around the square.

An article in Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leinster_Square) lists the following ‘notable residents’ of the square: the suffragette Georgina Fanny Cheffins (1863-1932); the musician Sting; and the architect Sir Charles Locke Eastlake (1836-1906). The article does not mention the naturalist William Henry Hudson (1841-1922), who lived at both numbers 11 and 16 Leinster Square.

William Henry Hudson

William Henry HudsonHudson was born in Quilmes, Argentina, son of parents of English and Irish origin, settlers from the USA. His father Daniel was son of a Devon man and an Irish mother. William’s mother was born in Maine (USA), a descendant of one of the Pilgrim Fathers. During his youth in Argentina, William made many observations about the local flora and fauna as well as human activity. Some of his findings, mainly ornithological, were published in the prestigious “Proceedings of the Royal Zoological Society” and were communicated to the Smithsonian Institute in the USA. His life, his works, his travels, and his extensive writings, have been described in detail in “WH Hudson. A Biography” by Ruth Tomalin.

On the 1st of April 1874, William departed from Argentina on board the “Ebro”, bound for Southampton in England, a journey that lasted 33 days. One of the first places Hudson visited was Clyst Hydon in Devon, where his father had lived. By the 22nd of December 1875, he had received his ticket for the reading room at the British Museum. It gave his address as 40 St Lukes Road, Bayswater. Known as the Tower House, this was a boarding house run by Miss Wingrave. The house, which still stands is at the corner of St Luke’s Road and Tavistock Road, close to Portobello Road. It bears two plaques commemorating the life of Hudson. It was in this house that he died. However, in between first arriving at this address and his final days, he lived in Leinster Square for a while.

Hudson’s hopes of gaining recognition in the scientific circles in London were disappointed. His romantic and artistic approach to natural history did not chime well with the London’s scientific elite with its more purely objective approach and its disdain for amateurs, however diligent they might be. And also, as Tomalin explained, Hudson did not:

“…belong to the right public school and university background.”

Unable and unwilling to join London’s somewhat dry academic community, Hudson, often short of money, wrote and published a great deal: fiction, non-fiction, natural history, travel, and poetry. On the 18th of May 1876, he married his landlady Emily Wingrave, once a professional singer (a soprano). His wife gave ‘no profession’ on the wedding certificate. She and William moved into number 16 Leinster Square, where she let out some of its rooms to paying guests. Although she claimed to be two years older than her husband, it was not for many years that he learned that she was 11 years older than him.

By 1878, the couple had moved into number 16 Leinster Square. Tomalin wrote of Emily:

“She gave him [i.e. Hudson] a home, companionship…, and a chance to devote himself to the slow unfolding of his gifts; something of the security of the mother and child relationship which, as his writings show, was often in his thoughts.”

After the Tower House came into the possession of Emily when her sister died, the Hudsons moved back there from Leinster Square, where the letting business had failed. Hudson was a keen opponent of cruelty to animal life and killing birds for collections. He was in touch with some women in Manchester, who founded the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Birds (‘RSPB’) in 1889. From the start he was a keen supporter of the RSPB and became the Chairman of its Committee in 1894.

In the summer of 1911, Emily became seriously ill and increasingly dependent of William’s assistance. After this, she suffered more bouts of illness. She died in March 1921. After her death, William rewrote his will, leaving much to the RSPB. Hudson died a year later in bed at Tower House, having just put the finishing touches on his last book, “A Hind in Richmond Park”.

This brief essay hardly does justice to the life of a remarkable naturalist, who criticised Charles Darwin in 1870, claiming, in connection with the great man’s fleeting observations a particular type of bird:

“… so great a deviation from the truth in this instance might give opponents of his book a reason for considering other statements in it erroneous or exaggerated…

…The perusal of the passage I have quoted from, to one acquainted with the bird referred to, and its habitat, might induce him to believe that the author purposely wrested the truths of Nature to prove his theory…”

The book referred to was Darwin’s “Origin of Species”. Hudson’s letter evoked a long and detailed response from Darwin, which was published in the “Proceedings of the Zoological Society”, which had also published Hudson’s criticisms. Although Hudson exonerated Darwin of having “wrested the truths of Nature … etc”, Darwin wrote in response:

“… I should be loath to think that there are many naturalists who, without any evidence, would accuse a fellow worker of telling a deliberate falsehood to prove his theory.”

Tomalin points out that Hudson’s criticism of Darwin was not surprising because he was not a believer in evolution as formulated by Darwin. Hudson believed in the theories of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829). Putting it extremely simply, Lamarck believed that, for example, giraffes developed long necks so that they could reach the highest of leaves, whereas as Darwin believed that variants of giraffes that grew long necks had a better chance of survival and propagation than variants which did not and were therefore less able to survive and multiply.

Hudson would have appreciated Leinster Square and its lovely garden, a haven for birds and plants, had he been able to see it today. He would have easily recognised Tower House in St Luke’s Road, which has apparently changed little since he lived there. Once again, keeping one’s eyes open even when walking somewhere familiar can often lead to exciting discoveries. It would take more than a lifetime of visiting the same place repeatedly to become familiar with each and every one of its varied aspects.

April 3, 2021

Gifts from India to an English village

LIFE DEPENDS ON WATER. A few days ago, at the end of March 2021, we drove to a village in Oxfordshire to see two old wells. They are no ordinary wells: they were gifts from India while it was still part of the British Empire.

Maharajah’s Well at Stoke Row

Maharajah’s Well at Stoke RowEdward Anderton Reade (1807-1886) was a British civil servant in India between 1826 and 1860. Brother of the novelist Charles Read (author of “The Cloister and the Hearth”), Edward was born in Ipsden, a village in Oxfordshire (www.oxforddnb.com/). He entered the East India Company in 1823. In 1832, he was transferred to Kanpur (Cawnpore), where he introduced opium cultivation to the district. In 1846, he became Commissioner to the Benares Division, a position he held until 1853 when he was moved to Agra.

Edward encouraged genial relations with the local Indian gentry and aristocracy. One of his Indian acquaintances, who became his good friend, was Ishri Prasad Narayan Singh (1822-1889), the Maharajah of Benares, who reigned from 1835 to 1889. During the years before the Indian Rebellion of 1857 (aka ‘First War of Independence’ or ‘The Indian Mutiny’), Reade and the Maharajah discussed much about England including the shortage of water that existed in Ipsden, the part of Oxfordshire where his family lived. Apparently, the villagers in this part of the Chiltern Hills had little or no access to clean drinking water, much as must have been the case for many villagers in India.

During the Rebellion of 1857, the Maharajah remained loyal to the British. In June 1857, the town of Kanpur was besieged by Nana Sahib and his forces. After 3 weeks, the British garrison surrendered under condition that the British inhabitants would be given safe passage out of the town. However, Nana Sahib decided to hold about 120 women and children and kept them housed in a house known as the ‘Bibighar’. This ended badly when some of the hostages were killed. Some of them tried to escape their grizzly end by jumping into a well at the Bibighar. This well became one of the most powerful images of the Rebellion in the minds of those who lived in Britain.

I do not know whether or not it was the tragedy at Bibighar that brought the conversations he had with Reade to the forefront of the mind of the Maharajah of Benares after the Rebellion was over, but in 1862, after his loyalty to the British had been formally recognised, he consulted Reade as to making a charitable gift to the poor people of Ipsden, whose plight he recalled. The Maharajah financed the construction of a well at Stoke Row, not far from Ipsden. It is also possible that the Maharajah remembered the help that Reade had given him when constructing a well in Azamgarh (now in Uttar Pradesh) back in 1831.

Work commenced on the well in March 1863. The well shaft was dug by hand, a perilous job for the labourers as they removed earth from the depths of an unlit and unventilated shaft, bucket by bucket. The shaft, 4 feet in diameter, was 368 feet in depth, greater than the height of St Pauls Cathedral in London, for this is depth of the water table at Stoke Row. Special winding machinery constructed by Wilder, an engineering firm in Wallingford, was installed. It is topped with a model elephant. The mechanism and the well stand beneath an octagonal canopy topped with a magnificent metal dome with circular glazed windows to allow better illumination. It resembles a ‘chhatri’ or architectural umbrella such as can be seen at war memorials on London’s Constitution Hill and on the South Downs near Hove. The structure, restored in recent times, looks almost new today. Reade, who helped plan the Maharajah’s well, planted a cherry orchard nearby; dug a fish-shaped pond (the fish was part of the Maharajah’s coat-of-arms); and constructed an octagonal well-keeper’s bungalow next to the well. The profits from the cherries harvested from the orchard were supposed to help to finance the well, for whose water the villagers were not charged anything. The Maharajah’s well at Stoke Row was the first of many such gifts given by wealthy Indians to Britain. Other examples include the Readymoney drinking fountain in Regents Park and a now demolished drinking fountain in Hyde Park, close to Marble Arch. According to the Dictionary of National Biography:

“Reade was wryly amused that an Indian prince should thus give a lesson in charity to the English gentry.”

The well at Stoke Row provided the locals with fresh water until the beginning of WW2, when, eventually, piped water reached the area. It provided 600 to 700 gallons of water every day. The Maharajah’s Well at Stoke Row is relatively well-known compared to another Indian-financed well next to the parish church at Ipsden, where Reade’s grave is located. The well, whose winding mechanism is similar to that installed at Stoke Row, is not covered by a canopy. It stands by a cottage next to the entrance to the churchyard. It was presented to Ipsden in 1865 by ‘Rajah Sir Deon Narayun Singh of Seidpor Bittree’ (I am not sure where this is: these are the words on the well), who had, like the Maharajah of Benares, remained loyal to the British during the 1857 Rebellion.

The Ipsden well is deep but not nearly as deep as that at Stoke Row. A lady, who lives in the cottage beside the well, told us that she had tasted water from the well and it was ice cold, deliciously clean, and tasted pure, having been filtered by many feet of chalk through which it has seeped. She said that once a year, the local water board opens the well and takes a sample of its water to check its purity.

Both wells are worth visiting. We parked in Benares Road in Stoke Row close to the Maharajah’s gift. After viewing the well head and its surroundings, we bought hot drinks at the village’s shop-cum-café, which his run by a couple of friendly people from Zimbabwe. I am grateful to Dr Peter U for bringing the existence of this unusual well to my attention.

April 2, 2021

A castle, a bridge, and the law

RIVER CROSSINGS HAVE often had great historical significance. The small town of Wallingford in Oxfordshire has been a place for crossing the River Thames since Roman times or maybe even before. According to “The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names” by someone with an interesting name: Eilert Ekwall, a fascinating book that I picked up for next to nothing at a local charity shop, the town was known as ‘Waelingaford’ in 821 AD, as ‘Welengaford’ in c893 AD, and ‘Walingeford’ in the Domesday Book. The meaning of the name is ‘The ford of Wealh’s people’, clearly referring to a river crossing place. It is said the William the Conqueror used the ford. Today, a fine bridge with many arches crosses the river.

Wallingford Castle

Wallingford CastleThere has been a bridge at Wallingford since 1141, or before. The construction of the first stone bridge was probably constructed for Richard, the first Earl of Cornwall (1209-1272), a son of King John, who became King of Germany (Holy Roman Empire) in 1256, a title he held until his death. Some of the arches of the bridge may contain stonework from the 13th century structure. Much of the present bridge dates from a rebuilding done between 1810 and 1812 to the designs of John Treacher (1760-1836). During the Civil War (1642-1651), four arches were removed and replaced by a drawbridge to help defend the besieged Wallingford Castle.

The huge castle was built on a hill overlooking the town; the river – an artery for water transport in the past; and, more importantly, the bridge, which was an important crossing place on the road leading from London to Oxford via Henley-on-Thames. Between the 11th and the 16th centuries, the castle was used a great deal, being used as a royal residence until Henry VIII abandoned it. During the Civil War, the castle was restored and re-fortified and used as a stronghold by the Royalists. It was of great importance to them as their headquarters were at nearby Oxford. To simplify matters, the Parliamentarians began laying siege to Wallingford Castle in 1645. This initial attempt was unsuccessful because the besiegers had underestimated the strength of the castle’s fortifications. After the Royalists were defeated at the Battle of Naseby (14th June 1645), Wallingford was one of only three strongholds in Berkshire (now in Oxfordshire) still loyal to King Charles I. A second siege of Wallingford commenced on the 14th of May 1646, shortly after the Parliamentarians had laid siege to Oxford. The latter fell on the 24th of June 1646, but Wallingford held out until the 22nd of July 1646 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wallingford,_Oxfordshire). The castle was demolished in November 1652.

The castle grounds are open to the public. Here and there, few and far between, there are ruins of what must have once been a spectacular castle. Within the grounds of the former castle, there are several informative notices that give the visitor some idea of which part of the castle used to stand near the signs. From the grassy areas that formed the motte and bailey of the castle, there are fine views of the river below and some of the town.

Although our first visit to Wallingford was brief, I learnt that the judge Sir William Blackstone (1723-1780) had presided as the Recorder at Wallingford from 1749 to 1770. “So, what?”, I hear you asking. At first, I hoped that he was something to do with the road, where we lived in Chicago (Illinois) in 1963: South Blackstone Avenue (number 5608). But I think that thoroughfare was more likely named after the American politician and railway entrepreneur Timothy Blackstone (1829-1900). The Wallingford Blackstone, who lived in the 18th century, was most probably a distant cousin of Timothy’s father (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timothy_Blackstone). Related or not, Sir William Blackstone had an extremely important influence the legal affairs of the USA.

Having studied at the University of Oxford and the Middle Temple, where he was called to the Bar, Sir William taught law at Oxford for a few years. Just before resigning his prestigious academic position in 1766, he published the first volume of what was to become a best-seller, a real money-spinner, “Commentaries on the Laws of England”. Eventually, this work was completed in four volumes. They contain:

“… first methodical treatise on the common law suitable for a lay readership since at least the Middle Ages. The common law of England has relied on precedent more than statute and codifications and has been far less amenable than the civil law, developed from the Roman law, to the needs of a treatise. The Commentaries were influential largely because they were in fact readable, and because they met a need.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commentaries_on_the_Laws_of_England)

The “Commentaries” are widely regarded as being the definitive sources of common law in America before the American Revolution. Blackstone’s writings were influential in the formulation of the American Constitution. His words embodied his vision of English law as a method of protecting people, their possessions, and their freedom. Blackstone’s ideas are well exemplified by this quotation from the “Commentaries”:

“It is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.”

This is known as ‘Blackstone’s Ratio’.

Leaders of the American Revolution recycled the idea with words such as:

“It is of more importance to the community that innocence should be protected, than it is, that guilt should be punished; for guilt and crimes are so frequent in this world, that all of them cannot be punished…” (John Adams; 1735-1826), and:

“…it is better 100 guilty Persons should escape than that one innocent Person should suffer…” (Benjamin Franklin; 1706-1790)

As already mentioned, Sir William presided in the court in Wallingford from 1749 onwards, three years after being called to the Bar. During his career, he served as a Tory Member of Parliament a couple of times: for Hindon (1761-68) and for Westbury (1768-70). In the House of Commons, he was:

“…an infrequent and ‘an indifferent speaker’: during the seven years 1761-8 only 14 speeches by him are recorded, mostly on subjects of secondary importance. Very learned and original, over-subtle and ingenious, in major debates he showed a lack of political common sense.” (www.historyofparliamentonline.org/vol...)

The Blackstone family owned a large estate at Wallingford including 120 acres of land by the River Thames. He died in Wallingford and was buried inside St Peter’s Church, which is close to the bridge over the river.

What little we saw of Wallingford, its castle, its riverside including the Thames towpath, its attractive market square, and streets rich in historic buildings, during our brief visit recently, we saw enough to whet our appetites for a future and lengthier visit.

April 1, 2021

In the footsteps of a great Indian politician

DURING THE FIRST ‘LOCKDOWN’, we spent a lot of time walking within two miles of our home. Despite having lived in Kensington for about 30 years, we wandered along many streets, which we had never visited until after March 2020. One of these many streets, which we ‘discovered’, is Aldridge Road Villas, a few yards south of Westbourne Park Underground station. On our first walk along this road, we met a man, who was repairing or restoring an old model of a Volkswagen parked near his home. Amongst his collection of old restored cars was an old Chevrolet truck, which we admired. We chatted with him and hoping to meet him again, we revisited Aldridge Road Villas several more times, sometimes meeting whilst he was working on one of his vehicles. Because we tended to walk along this road hoping to meet him, we managed to miss something else of great interest to us. It was only recently, that I spotted what we had been walking past without noticing it.

Statue of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel in Gujarat, India

Statue of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel in Gujarat, IndiaAldridge Road Villas is probably named after the Aldridge family, who had owned land beside the Harrow Road at Westbourne Park since 1743 or before. The barrister, member of Lincoln’s Inn, John Clater Aldridge (c1737-1795), who became MP for Queensborough between 1780 and 1790 and then for Shoreham between 1790 and 1795, married Henrietta Tomlinson, widow of William Busby and a wealthy landowner, in 1765 (www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/aldridge-john-clater-1737-95). Through this marriage, John came into possession of more land around Westbourne as well as some near Bayswater. It is on this land that Aldridge Villas Road was built (www.theundergroundmap.com/article.html?id=10787). The oldest houses on the street date from the middle of Queen Victoria’s reign. A map surveyed in 1865 shows that the road was already lined with houses by that date.

One former resident of Aldridge Villas Road, at number 1, was the surgeon George Borlase Childs (1816-1888), who was born in Liskeard, Cornwall. A biography (https://livesonline.rcseng.ac.uk/) reveals that he was:

“…connected with the Metropolitan Free Hospital for many years, but is perhaps best remembered as Surgeon-in-Chief to the City of London Police, and to the Great Northern Railway. He took, indeed, a large share in organizing the medical departments of these institutions, displaying on a wider field the characteristic forethought and ingenuity of his work as an operator. The sanitary and physical well-being of the City policeman was one of his prime interests. He devoted much thought and care to the process of selection of members of the force, to their housing and their dress. The last-mentioned is, in fact, his creation, for he introduced the helmet as we now know it, the gaiters, and so forth. He also established the City Police Hospital…”

Celebrated as he should be, it is not Childs who was the best-known resident of the short road near Westbourne Park station. Although he did not live for a long time in the street, the most famous inhabitant of Aldridge Road Villas must be Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel (1875-1950). It was the plaque affixed to a five-storey terrace house, number 23, which had avoided our attention the first few times that we walked along the road.

Like many other Indians living under British rule in India, who became involved in political activity, including Mahatma Gandhi, Shyamji Krishnavarma, Bhimrao Ambedkar, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Patel decided to sail to England to study. Vallabhbhai set sail from Bombay in July 1910. On arrival in London, he stayed briefly at the then luxurious Hotel Cecil in the Strand. After that, he stayed in a series of ‘digs’ in different parts of London while he completed his legal training. One of these was for several months at 23 Aldridge Road Villas, the address that appears in his records following his admission to The Middle Temple to become a barrister on the 14th of October 1910 (https://middletemplelibrary.wordpress.com/2020/04/08/famous-middle-templars-3/), the same year as that in which Jawaharlal Nehru joined Inner Temple. Patel was called to the Bar on the 27th of January 1913 (www.telegraphindia.com/india/alma-mat...). Incidentally, many years later my wife was also called to the Bar at Middle Temple, as had also been the case, many years earlier, for my wife’s great grandfather and his father-in-law.

Patel was hard up as a student in London:

“After his arrival in England, he joined Middle Temple and allegedly studied at least 11 hours a day. Because he was not able to afford books, he used the services of the Middle Temple Library where he spent most of his days.” (https://middletemplelibrary.wordpress.com/2020/04/08/famous-middle-templars-3/).

This shortage of money might well have been the reason that he walked between his digs and the library every day. His biographer, Rajmohan Gandhi, a grandson of Mahatma Gandhi, wrote in “Patel. A life”:

“His twice daily walk between Aldridge Villas Road, Bayswater and the Middle Temple – 4 ¾ miles each way – took him past parks and edifices of great charm or magnificence, including Kensington Gardens, Buckingham Palace, St James Park, Cleopatra’s Needle and Waterloo Bridge. When he moved digs his walks were as long or longer but not less scenic.”

Gandhi lists Patel’s other London digs as 62 Oxford Terrace, 2 South Hill Park Gardens, 57 Adelaide Road, and 5 Eton Road. With the exception of Oxford Terrace, the other did were near Belsize Park and Swiss Cottage.

Back in India, Patel became involved in the struggle for Indian Independence, joining Mahatma Gandhi and the Indian National Congress Party. Like many other freedom fighters Patel served several terms in prison. After WW2, he was significantly associated with negotiations with the British regarding transfer of power to the Indians. In 1947, when India became independent, the country consisted of areas that were directly under British rule and well over 800 Princely States that were allowed some independence providing that their rulers did not do anything to challenge the overriding authority of the British Empire. Sardar Patel oversaw and encouraged the rulers of these Princely States to give up their supposed sovereignty and to become part of a new unified India. This was no easy task because some of the larger states, notably Junagarh, Kashmir, and Hyderabad, wished to become part of the recently created Pakistan instead of India. Some considerable persuasion was required to get these places to merge with India. Patel’s achievement at unifying India must surely rival that of Otto Von Bismarck, who unified the myriad German states to become one country by 1871.

The plaque in Aldridge Road Villas is a modest and almost discreet memorial to the great Patel. If you wish to see a more spectacular monument to this remarkable man, you will need to travel to Gujarat in western India, where an enormous statue of him, almost 600 feet high, was completed in 2018. Called ‘The Statue of Unity’, its bronze plates and cladding were cast in the Peoples Republic of China.

Usually, we walk south along Aldridge Road Villas. Until we spotted the plaque commemorating Patel’s residence in the road, we had not realised that we were likely to have been following in the footsteps of one of India’s greatest politicians, which he made when he set out for Middle Temple every morning. And, the idea that one is often walking where famous figures of the past have trod is yet another thing that makes London so wonderful for both residents and visitors alike.

March 31, 2021

Grahame Greene got married here

DURING THE COVID19 ‘lockdowns’, it is often impossible to venture within a church. On several occasions, especially when there are builders at work within a church, we have been lucky enough to be able to enter it. Otherwise, they are usually locked up. Not too long ago, I wrote about General De Gaulle’s brief period of residence in Hampstead and mentioned that he attended mass at Hampstead’s Roman Catholic St Mary’s Church (https://adam-yamey-writes.com/2021/03/22/french-connections/). Oddly, given how often we have visited Hampstead, I had never seen St Mary’s until we visited it in late March 2021. The church is located on Holly Walk about 180 yards north of Hampstead’s Anglican Parish Church.

St Mary’s is set back from the road and its tall narrow façade is wedged between two terraced Georgian houses. The white painted façade with neo-classical ornamentation and a niche containing a large sculpture of the Virgin and Child, and a belfry with a single bell, has a Mediterranean or southern European look to it. It adds an exotic touch to its otherwise British surroundings. The façade was designed by the architect William Wardell (1823-1899), many of whose creations are in Australia. Born a Protestant, he was influenced by his friend the great Victorian architect Augustus Pugin (1812-1852), who converted to Roman Catholicism. Wardell followed in Pugin’s footsteps and became a Catholic, building several Catholic churches in England, including St Mary’s in Hampstead, before he moved to Australia in about 1858 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Wardell). In the 1840s, after becoming a Catholic, he became a parishioner at St Mary’s.

Prior to the construction of St Mary’s, the Roman Catholics in Hampstead worshipped in Oriel House in Little Church Row. When this became too small to accommodate the congregation, the present church was constructed in under a year and was ready for use in August 1816. At that time, the congregation was led by a French refugee, the Abbé Jean-Jacques Morel, whom I described in the article to which I referred above. While he was still officiating at St Marys, a Papal Bull, the “Restoration of the Hierarchy to England and Wales”, was issued in 1850. Included in this document was permission for bells to be rung from Catholic churches in England for the first time since the Reformation. It was this that led to the creation of the façade, designed by Wardell, which we see today.

Fortunately for us the door to the church was open when we arrived. A couple of workmen were doing some repairs and did not mind us entering the small church. According to Nikolaus Pevsner and Bridget Cherry in their “London 4: North” architectural guide, the interior was altered in 1878, and a sanctuary as well as two side chapels were added in 1907. The nave faces a baldachino supported by four pillars coloured black with gold-coloured decoration. The baldachino was designed by Adrian Gilbert Scott (1882-1963) in 1935. His family were parishioners of St Mary’s. Adrian lived in Frognal Way in a neo-Georgian house called Shepherd’s Well. Sir George Gilbert Scott (1811-1872), Adrian’s grandfather, also lived in Hampstead, at Admirals House close to Fenton House. There is a painting above the high altar that depicts the Assumption of the Virgin. This was painted by a student of Bartolomé Murillo (1617-1682) and presented to the church by one of its founders Mr George Armstrong.

There is a stone effigy in the northern side chapel, the Lady Chapel. It depicts a figure with hands together as in prayer, with a lion at his feet. Although Abbé Morel had requested to be buried under a simple marble slab, this effigy of him was commissioned by the architect Wardell. The lion at the feet of the cleric indicates that he died outside the country of his birth.

Although the interior of the church is not so old, it evokes the feeling of much older churches I have seen in Italy. As with the façade, the inside of St Mary’s feels as if it is in a country close to the Mediterranean. While visiting its interior, I popped a donation into a box in exchange for a copy of a booklet about the church, from which much of my information has been gleaned. The booklet includes information about some notable members of the church’s congregation, including General De Gaulle, the Duchess of Angouleme, William Wardell, the Gilbert-Scott family, the landscape artist Thomas Clarkson Stansfield (who lived on Hampstead High Street), the novelist Grahame Greene (1904-1991), and Baron Friedrich Von Hugel (1852-1925).

Greene, an agnostic, became converted to Catholicism and was baptised in February 1926, partly because of the influence of Vivien Dayrell-Browning, whom he married in October 1927 in the Church of St Mary’s in Hampstead.

Von Hugel, who lived in Holford Road, which runs east of Heath Street, was, like Greene, a convert to Catholicism. He was born in Florence, Italy, and moved to England when he was 15 years old. He was an influential religious historian and philosopher both inside and beyond the Roman Catholic Church. He was a leading proponent of Catholic Modernism, which:

“…is neither a system, school, or doctrine, but refers to a number of individual attempts to reconcile Roman Catholicism with modern culture.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modernism_in_the_Catholic_Church).

Less cerebral than Von Hugel, but greatly skilled was Gino Masera (1915-1996), who worshipped at St Mary’s. The booklet describing the church notes that when working at London’s Savoy Hotel:

“His artistic talent was revealed when he was asked to carve a block of salt for table decoration. He regarded the commission to carve the Stations of the Cross [in St Mary’s] as a turning point in his career and went on to carve the statue of Christ the King which stands above the High Altar in St Paul’s Cathedral.”

St Mary’s Church stands above a large burial ground that lines the east side of most of Holly Walk. Less picturesque than St Mary’s, this cemetery contains some interesting gravestones including those of the actor Anton Wohlbrueck (Walbrook) who died in Germany but whose ashes are buried in Hampstead; the cartoonist George du Maurier; and the Labour politician Hugh Gaitskell.

Once again, visiting Hampstead, a district with a rich history has proved interesting. Each time we make a trip to the area, we see things we had not noticed before and this has resulted in gradually expanding our knowledge of a place that has attracted fascinating people as residents over several centuries.