Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 167

March 20, 2021

King Richard III and more

SEEN FROM ACROSS THE THAMES at Battersea Park, it looks like a Tudor palace in immaculate condition on the opposite bank of the river. But do not be fooled because much of Crosby Hall, the edifice you can see from the riverside at Battersea, was built between 1910 and about 1926. Part of the building is far older, dating back to mediaeval times and it was moved from the heart of the City to its present location in Chelsea in 1910. Let me explain, please.

In 1466, Sir John Crosby, alderman and a sheriff of London, built his mansion, Crosby Place, on land just east of Bishopsgate, leased to him by the Prioress St Helens Bishopsgate, a church nearby. After Crosby died in 1475/6, Crosby Place was owned by the Duke of Gloucester (1452-1485), who was to become King Richard III, of Shakespearian fame. John Timbs in his “Curiosities of London” (published in 1855) suggests that in 1598, Shakespeare had lodgings close to Crosby Place. In Act 1, scene 2 of his play, Richard, Duke of Gloucester says:

“And presently repair to Crosby House;

Where (after I have solemnly interr’d

At Chertsey monast’ry this noble king,

And wet his grave with my repentant tears)

I will with all expedient duty see you.

For diverse unknown reasons, I beseech you,

Grant me this boon.”

Writing in 1603 in his “The Survey of London”, John Stow (1524/25-1605) noted:

“Then you have one great house called Crosby place, because the same was built by Sir John Crosby, grocer and Woolman … This house he built of stone and timber, very large and beautiful, and the highest at that time in London … he was buried in St Helen’s, the parish church…”

Stow also recorded that in the late 16th century several ambassadors lived in the house.

The fourth owner of Crosby Place was the senior government official, Sir Thomas More (1478-1535), whose head was removed at the Tower of London after disagreements with his ‘boss’, King Henry VIII. It has been suggested by Timbs that More wrote his books “Utopia” (1516) and “History of Richard the Third” (1512-1519) whilst residing at Crosby Place. In 1523, More sold Crosby Place to his friend, the banker and merchant Antonio Bonvisi (died 1558) from Lucca in Italy. Interestingly, More moved to his house in Chelsea after leaving Crosby Place. His riverside home, the former Beaufort House was a few yards away from the present Crosby Hall.

The ownership of Crosby Place changed several times after More sold it. Sir Walter Raleigh lived there in 1601. Between 1621 and 1638, the Place was home to the East India Company (founded 1600). Soon after 1642, fire struck the property, and it was never again used as a residence. The conflagration spared the great hall, which became known as Crosby Hall. During the Civil War, it was used as a prison for Royalists. In 1672, it was converted into a Presbyterian meeting house, and was used as such until 1769. Next, the hall was used as a packer’s warehouse. The packer’s lease expired in 1831. Following that and public concern about its condition, the hall was restored in about 1836. Timbs noted that it was:

“… the finest example in the metropolis of the domestic mansion Perpendicular work … The glory of the place is, however, the roof which is an elaborate architectural study, and decidedly one of the finest examples of timber-work in existence. It differs from many other examples in being an inner roof…”

From Timbs’s detailed description, it sounds as if it was a spectacular creation.

Following its restoration, Crosby Hall became used for musical performances and as a meeting place for literary societies. In 1868, Crosby Hall became a restaurant. The Hall was sold to the Chartered Bank of India, Australia, and China in 1907. The bank wanted to destroy what was one of the oldest buildings in the City of London, one of the few survivors of the Great Fire of 1666. These plans caused a public outcry. In 1910, the Hall was dismantled and moved stone by stone to its present site in Chelsea, opposite Battersea Park. There, it was reassembled and Tudor-style additions, designed by the architect Walter Godfrey (1881-1961) were constructed.

During WW1, the relocated and enlarged Crosby Hall was used to house refugees from war-torn Belgium. Between 1925 and 1968, the Hall was leased by the British Federation of University Women. Following the anti-Jewish laws passed by the Nazis in 1933, Crosby Hall provided residential fellowships for Jewish women academics who had fled from Hitler’s Germany. After 1988, Crosby Hall became a private residence (www.christophermoran.org/news/crosby-hall-the-most-important-surviving-domestic-medieval-building-in-london/).

Close to the relocated Crosby Hall there is a statue of Sir Thomas More, seated and looking across the Thames. This statue is appropriately located between what is left of his old home, which used to be in Bishopsgate, and the land on which his Chelsea mansion used to stand. One day, I hope that I will be able to see the superb hammer beam roof in Crosby Hall. I wonder how it compares with the wonderful example that can be seen in Middle Temple Hall, in which Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night” was first performed in 1602.

March 19, 2021

Beef, mutton, and martyrs

COPENHAGEN FIELDS WAS an open space north of the Barnsbury district of London’s Islington. In the 17th century, the place was beyond the northern edge of London. As with other open spaces in 17th century Islington, it was an area where people whose homes had been destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 congregated with what belongings they managed to salvage. By the 18th century, Copenhagen Fields had become a place where large numbers of Londoners used to gather for political meetings.

Animals being led to Caledonian Market

Animals being led to Caledonian MarketAccording to William Howitt writing in his “The Northern Heights of London” (published in 1869), the fields acquired its name following a visit of the King of Denmark to his relative King James I (reigned over England, Scotland and Ireland from 1603 to 1625). A Dane built a house on the open space, Copenhagen House. The name ‘Copenhagen’ appears on a map published in 1695. Howitt reveals that Copenhagen Fields and its house became a place of recreation for Londoners:

“It became a great tea house and resort of the Londoners to play skittles and Dutch-pins. It commanded a splendid view over the metropolis, the heights of Highgate and Hampstead …”

As mentioned, Copenhagen Fields was connected with political activity; it was a place of mass protests. Not long after the French Revolution, there was a meeting in the open space:

“On the 12th of November 1795 a public meeting was summoned by the London Corresponding Society in Copenhagen Fields which was attended by more than a hundred thousand persons. Five rostra or tribunes were erected, and Mr. Ashley, the secretary, informed the meeting that it at each of them petitions to the King, Lords and Commons against the Bill for preventing seditious meetings would be offered to their consideration.” (www.historyhome.co.uk/c-eight/france/copenhagen.htm).

The best remembered protest that occurred in Copenhagen Fields was on the 21st of April 1834. Thousands of people commenced marching from there to central London in support of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, who lived in Dorset:

“In 1834, farm workers in west Dorset formed a trade union. Unions were lawful and growing fast but six leaders of the union were arrested and sentenced to seven years’ transportation for taking an oath of secrecy. A massive protest swept across the country. Thousands of people marched through London and many more organised petitions and protest meetings to demand their freedom.” (www.tolpuddlemartyrs.org.uk/).

Many of those marchers began their procession from Copenhagen Fields:

“Up to 100,000 people assembled in Copenhagen Fields near King’s Cross. Fearing disorder, the Government took extraordinary precautions. Lifeguards, the Household Cavalry, detachments of Lancers, two troops of Dragoons, eight battalions of infantry and 29 pieces of ordnance or cannon were mustered. More than 5,000 special constables were sworn in. The city looked like an armed camp.

By 7am the protesters began to gather marshalled by trade union stewards on horseback. Robert Owen, the leader of the Grand Consolidated Union and the father of the Co-operative Movement arrived.

The grand procession with banners flying marched to Parliament in strict discipline. Loud cheers came from spectators lining the streets and crowding the roof tops. At Whitehall the petition, borne on the shoulders of twelve unionists, was taken to the office of the Home Secretary, Lord Melbourne. He hid behind his curtains and refused to accept the massive petition.” (www.tolpuddlemartyrs.org.uk/story/mounting-protest)

In June 1855, Queen Victoria’s Consort, Prince Albert, opened the Metropolitan Cattle Market (later known as ‘Caledonian Market’). This market occupied most of the area of Copenhagen Fields. It was built to ease the congestion caused by driving live animals into the more centrally located Smithfield Market. Although at first many animals walked to the market from the fields where they were raised, the market was built close to the goods yards of the recently built Great Northern and North London railways (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metropolitan_Cattle_Market).

Cattle travelled (under their own ‘steam’) two hundred miles from Devon at two miles per hour, walking twelve hours a day. Sheep from Wales, also two hundred miles from Copenhagen Fields, would be trotting across England to London for twenty days. Some cattle travelled even further: over five hundred miles from Scotland. These fascinating figures can be seen on a sign located in the park that stands where the cattle market stood between 1855 and the early 20th century, when trade in live animals began to decrease. Later, the market area was used for selling antiques and bric-a-brac. The Caledonian Market finally closed in 1963.

Much of the old market area is now used for recreation. On the south side of Market Road, there are enclosed sporting areas. The northern side is an attractive little park. All that remains of the market are the Victorian cast-iron railings, which are in various states of decay, and the market’s clock tower, which has been beautifully restored. The tower is 151 feet tall. It used to stand amidst the now-demolished dealers’ offices and close to the also demolished abattoirs.

Just north of the tower, there is a small café which is named in honour of the Tolpuddle Martyrs. Within it, there is a wall facing the serving counter. This has two murals commemorating mass protest. One of them, painted in a style reminiscent of social realism depicts people of many different ethnicities marching beneath a banner of The Islington Trades Union Council. This bears the words:

“Reclaim our past. Organise our future”.

The other mural commemorates the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

Panels on the walls of the café and around the north entrance to the park are decorated with scenes from the history of the area in the form of silhouettes. Some of them show animals being driven through the countryside. Others depict market scenes and the shops in which the meat was sold. Circular panels mounted on the walls of the tower show old photographs of the market in its heyday.

Although the park is not as spectacular as many other London parks, it is worth visiting to see the magnificently restored market clock tower and the several plaques and illustrations that provide clear explanations of the area’s historical importance. In addition, the small café and surrounding buildings within the park are good examples of contemporary architecture. The Caledonian Park, the former Copenhagen Fields, is yet another fascinating feature that contributes to what is wonderful about London.

March 18, 2021

Huguenots and Catholics in London’s Soho

SOHO SQUARE IN London’s West End contains two places for Christian worship: St Patricks Church (Roman Catholic); and The French Protestant Church. After Henry VIII came to the throne, life in Britain began to become awkward and sometimes dangerous for Roman Catholics. At around the same time, the same was the case for French Protestants (the Huguenots) across the English Channel in France. Life for the Huguenots was perilous in their native land. For example, in 1545 several hundred Waldensians, people who questioned the truth of the teachings of the Catholic Church, were massacred in Provence, and about ten years before that, more than 35 Lutherans were burnt elsewhere in France. Things got worse for the French Protestants during The Eight Wars of Religion (1562-1598; https://museeprotestant.org/en/notice/the-eight-wars-of-religion-1562-1598/). Even before the war broke out, Huguenots began fleeing to places where Protestantism was either tolerated or encouraged. England was one of these. Under the Tudors, the country became home to Huguenot refugees from France and Holland.

[image error]When the Huguenots began arriving in London, that is during the 16th century, the metropolis covered mainly what is now the City of London and areas just east of it such as Spitalfields. So, it was in what is now the City and East End that the Huguenots settled and added significantly to the richness of London life. Fournier Street in Spitalfields is one of several streets where they worked and lived. As the centuries passed, London expanded westwards and what some now call the West End began to be developed. Soho Square was built in the 1670s. As increasing numbers of Protestant refugees arrived in England, some of them settled in the newly developed western parts of London. Writing in his “Huguenot Heritage” Robin D Gwynn noted:

“If Huguenot taste made an impression in the cramped quarters of Spitalfields, it was stamped more deeply on the life of the nation through the work of the refugee settlement in Westminster and Soho. Here was the centre of French fashion, cuisine and high society in England, located conveniently near Court and Parliament.”

The churches used by the Huguenots in London were mainly in Spitalfields before the West End was built. By the 18th century, there about 14 in Westminster and Soho. By the 18th century, there were 31 Huguenot churches and their number increased to such an extent that the Anglican Church began to feel that its churches were becoming outnumbered in London. A version of the Marriage Act that was in force between 1753 and 1856:

“…required marriages other than those of Jews and Quakers to take place in a Church of England church, and led to the demise of some French churches. Some Huguenots of Spitalfields chose Christ Church as their place of worship. It was also the case that Huguenots gradually assimilated and intermarried into English society during the century since their arrival, eliminating the need for separate French churches.” (www.thehistoryoflondon.co.uk/huguenots/2/)

By the latter part of the 19th century:

“Soho was London’s major French neighbourhood and was therefore the obvious setting to build a new church …” (www.egliseprotestantelondres.org.uk/e...)

The church that was constructed is that which is located on the west side of the northern edge of Soho Square and was completed in 1893. It was designed by Aston Webb (1849-1930), who also designed a façade on the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington. The ornamental details on the mainly red stone façade were created by William Aumonier (1841-1914), a sculptor with some Huguenot ancestry. A bas-relief in the demi-lune above the main entrance attracted my attention. On the left, there is a depiction of a crowded sailing ship. On the right, there is a man holding a document, which is being signed by a man (a king) holding a quill pen. Both panels are surmounted by angels. The base of the sculpted demi-lune has the following inscription:

“To the glory of God & in grateful memory of HM King Edward VI who by his charter of 1550 granted asylum to the Huguenots of France.”

Edward the Sixth (lived 1537-1553) was only nine years old when he succeeded his father King Henry VIII, yet even at this tender age he was an ardent promoter of Protestantism as the state religion. Following the visits to London by Protestant leaders such as John Laski (Jan Łaski or Johannes à Lasco (1499 – 1560), King Edward VI issued Letters Patent, which permitted the establishment of the (protestant) Dutch and French churches of London. Robin Gwynn wrote that:

“The nature of the letters patent was most unusual. In an age which set great store on stringent religious conformity, they allowed foreigners in London to worship … freed even from the jurisdiction of the Bishop of London.”

A reason that Edward VI might well have sanctioned these foreign Protestant churches was because he hoped that they would be, to quote Gwynn:

“… the model, the blueprint, for a pure, reformed Church of England. The twin refugee churches [i.e. French and Dutch*] offer us a window into the future envisaged by Edward, a future in which there might be superintendents but not bishops.”

Laski had been a superintendent in Emden before he came to England. As such, he:

“… instituted the first example in England of fully-fledged reformed Protestant discipline, based on elected, ordained ‘elders’.”

At the end of Edward’s short reign and his successor Lady Jane Grey’s even shorter one, Queen Mary, a committed Catholic, temporarily put the brakes on the advancement of Protestantism in Britain, and Laski fled to the European mainland with some of his congregation.

The Roman Catholic Church of St Patricks that stands close to the French church was designed by John Kelly (1840-1904) and built between 1891 and 1893 on the site of one of the first Catholic buildings to be allowed in England after the Reformation (which countered Catholicism). It is interesting to note that many of the Catholics who came to London (from, for example Italy and Ireland) over the centuries were economic refugees rather than religious fugitives, as were the Huguenots.

Despite the passage of time, Soho remains a richly cosmopolitan district of London. Although there are fewer than in than in the past, the area is still home to some fine purveyors of imported foods, notably delicious ingredients from Italy. Back in the 1960s, when I was a child, my mother used to do much our food shopping in these stores as well as in French and Belgian shops, which have long since closed. The disappearance of shops such as these is probably partly a reflection of the migration of members of communities such as the Huguenots out from the centre of town to the suburbs.

*Note: the Dutch Church is currently in Austin Friars in the City. It was first established in 1550.

March 17, 2021

A pyramid at Glastonbury

THE FIRST PYRAMIDICAL STAGE at the site of the annual music festival at Glastonbury was built in 1971. It was designed by Bill Harkin, who died on the 11th of March 2021, aged 83. He was inspired by a dream he had back in 1970. The story goes as follows (https://www.avalonianaeon.com/content/bookextracts_content_text.html):

“The contents of ‘The View Over Atlantis’ hung in the air, like an esoteric energy transmission, around the inception of the 1971 Pilton festival. Powerful forces were at work. The story of the famous pyramid stage is a good example. In 1970 Bill Harkin was camping with a friend on the south coast of England. One night, gazing at the stars over the sea, he experienced an intense feeling of light. He decided to allow himself to be guided by it and they set off in his car, navigating solely through the vibe, with no sense whatever of any destination. Eventually they saw a road-sign for Glastonbury and arrived at the Tor. The synchronisation beam got them there in time to meet a group of extravagantly dressed hippie characters descending from the summit. One of them was Andrew Kerr. He and his friends were on their way to meet Michael Eavis to discuss the possibilities of a solstice festival the following year. Harkin fed them with tea, honey and oatcakes. They exchanged phone numbers. The next Wednesday, Harkin was out driving when he saw a vision of Andrew Kerr’s face on an upcoming phone-box. He immediately stopped and rang him. The news was that the festival had been given the go-ahead and that Kerr and his associates were moving into Worthy Farm to begin the preparations. Harkin offered to help them that weekend. On the Thursday night he dreamt of a stage with two beams of light forming a pyramid … Within a few days he arrived on the festival site. Kerr showed him a location he had dowsed as being auspicious for the stage to be constructed upon. Harkin recognised his dream landscape. Before long, his model was on a table at the farm and a phone call was being made to John Michell for advice on the sacred dimensions for the pyramid stage.”

Bill Harkin

Bill HarkinThose of you who are kind enough to read the daily essays, which I post on Facebook, or, after a short delay, on my blog (http://www.adam-yamey-writes.com), might recall that recently I wrote (https://www.facebook.com/YAMEY/posts/10224916932141143) about John Michell, who lived in Notting Hill, west London. This is the same John Michell as that mentioned in the long quote above. “The View over Atlantis” was one of Michell’s most successful books. Michell was deeply involved with the mathematics and geometry of esoterica (in my opinion) such as ley-lines and unexplained phenomena that he believed to be the basis of civilisation, which he believed had been introduced to mankind by visiting extra-terrestrial aliens.

The stage was:

“… conceived by Kerr and the designer Bill Harkin as a one-10th scale replica of the Great Pyramid at Giza. Harkin told me, “I had a dream about standing at the back of a stage and seeing two beams of light forming a pyramid and took that as a message. Andrew gave me John Michell’s number and we spent some hours discussing it…” (www.independent.co.uk/news/people/andrew-kerr-writer-and-festival-organiser-man-who-helped-make-glastonbury-festival-stunning-success-9783179.html)

In his book “The View over Atlantis”, published in 1969, Michell had:

“… recently elucidated the spiritual engineering which, he says, was known over the ancient world.”

According to Michell:

“…All bodies in the universe , according to Michell, give off natural energy. The combinations of these energies , existing when a man is born , makes up one quarter of his character. At the summer solstice, energies from the planets, the sun and the constellation are at their height. The earth gives of[f] energies through certain values in its surface, called blind springs. The Great Pyramid in Egypt, Stonehenge itself and the great pre-reformation Gothic churches were designed to accumulate this terrestrial current, to conduct the solar spark and to fuse the two.”

(both quotes from www.ukrockfestivals.com/glasmenu.html)

Andrew Kerr, the creator of the festival, hoped that the pyramid designed by Harkin to the measurements that Michell had based on celestial geometry would on one of the days of the festival:

“… concentrate the celestial fire and pump it into the planet to stimulate growth.”

Whether or not it did so, I cannot say, but the Glastonbury Festival has thrived since 1971, but it had to be cancelled in 2020 because of the covid19 pandemic.

Was it pure coincidence that I happened to write about Michell and ideas, which are usually way off my radar, a few days before Harkin died? Or were my thoughts conveyed mysteriously along an invisible ley line that happened to intersect with that along which Harkin was travelling? Just because strange phenomena that fascinated the brilliant mind of John Michell cannot be pinned down by conventional scientific method, it is best to keep an open mind about their existence or non-existence.

March 16, 2021

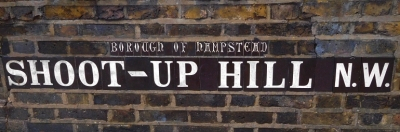

Shoot up in north London

THE ROMANS BUILT straight roads when they occupied Britain. Watling Street, which linked Dover (in Kent) and Wroxeter (in Shropshire) via London, was no exception. London’s Edgware Road, part of the A5 main road, follows the course of Watling Street. It connects Marble Arch with Edgware. A short section of this road travels over a hill between Kilburn Underground station and the start of Cricklewood Broadway, about 840 yards away. This aesthetically unremarkable stretch of the former Watling street is called Shoot Up Hill. Although it is hard to imagine by looking at this non-descript portion of one of London’s main thoroughfares, its name is associated with the history of the area of northwest London known as Hampstead.

Also known in the past as ‘Shuttop’ or ‘Shot-up’, Shoot Up was the name of a mediaeval manor or an estate, which was part of the Manor of Hampstead. The land with the name Shoot Up (or its variants) was part of the Temple Estate, which was granted to the Knights Templars in the 12th century (https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol9/pp91-111). In 1312, the Pope dissolved the Order of the Templars and transferred its possessions to the Knights Hospitallers of St. John of Jerusalem. By the 14th century, the Watling Street marked the estate’s western boundary, as well as that of the Manor of Hampstead. The Hospitallers were dissolved in 1540 by King Henry VIII.

One of the king’s officials involved in the dissolution of religious orders such as the Hospitallers was Sir Roger de Cholmeley (c1485-1565), the man who founded Highgate School in 1565, the school where I completed my secondary (‘high school’) education. One of his recent biographers, Benjamin Dabby, relates in his “Loyal to The Crown. The Extraordinary Life of Sir Roger Cholmeley” that in 1546, Sir Roger was granted the:

“… the lordship and manor of Hampstead Midd. [i.e. Middlesex], and lands in the parishes of Wyllesden and Hendon, Midd. …”

He was granted these lands which he helped to take from the Hospitallers. Dabby wrote that his newly acquired estate was known as ‘Shut Up Hill’ or ‘Shoot Up Hill’ Manor and that it consisted of:

“… some two hundred acres of arable land, fifty acres of meadow, two hundred of pasture, one hundred and forty of wood, and one hundred of waste, in the parishes of Hampstead, Willesden, and Hendon.”

It was a valuable estate, and being a landowner gave him enhanced status in Court circles. Income from this estate helped finance the school that Sir Roger created shortly before his death. Unlike others of his status, Sir Roger was uneasy about the signing of the document that brought the unfortunate Lady Jane Grey to the throne. This allowed him to escape execution when Queen Mary succeeded her as monarch. Instead, he was imprisoned briefly and fined.

The Shoot Up Manor (or Estate), which remained in the northwest corner of Hampstead Parish, passed through various owners after the death of Sir Roger. Until the 19th century when most of it was developed for building, there was little in the way of buildings on the land. A history of the area (https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol9/pp91-111#p41) revealed:

“There is unlikely to have been a dwelling house on the Temple estate earlier than the one which the prior of the Hospitallers was said in 1522 to have made at his own expense, a substantial dwelling house with a barn, stable, and tilehouse. It was probably on the site of the later Shoot Up Hill Farm, which certainly existed by the 1580s, on Edgware Road just south of its junction with Shoot Up Hill Lane. The farm buildings remained until the early 20th century.”

A map surveyed in 1866 shows that what is now Edgware Road was built-up as far as the railway bridges where Kilburn station is located, but north of this, Shoot Up Hill ran through open country, passing a flour mill (‘Kilburn Mill’) where the current Mill Lane meets the Hill, on the west side of the road.

Today, Shoot Up Hill is lined on its eastern side by large dwelling houses, mostly divided into flats. The western side is occupied mainly by large purpose-built blocks of flats. One of these architecturally undistinguished blocks is appropriately named Watling Gardens. As for origin of the name Shoot Up Hill, this is unknown. It is extremely unlikely that it has anything to do with firing weapons. If the traffic is heavy, you will have plenty of time to meditate on its possible origin, otherwise you will hardly notice it as you speed along it.

March 15, 2021

Accident in Orange

ONE EASTER DURING the late 1990s, we drove to Provence in the south of France. There, we hired a lovely rural cottage (a ‘gîte rural’) located on the edge of a village next to an orchard of trees overladen with ripe cherries. That year, there was a heatwave in the south of France, daytime temperatures reaching and staying at 37 degrees Celsius. We were pleased that our Saab saloon car had built-in air-conditioning and that our gite had a large garden and a shady terrace.

Roman amphitheatre, Orange, France

Roman amphitheatre, Orange, FranceDespite the high daytime temperatures, we managed to do plenty of sight-seeing. One day, we decided to explore the delights of the city of Orange, which was not far from our gite. The city is rich in Roman remains including a magnificent open-air theatre with steps, on which the audience perched, arranged in a circle.

In the 12th century, Orange and its surroundings became a principality within the Holy Roman Empire. In 1554, William the Silent, Count of Nassau, who had possessions in the Netherlands and became a Protestant, inherited the title ‘Prince of Orange’. The Principality of Orange was incorporated into what became the House of Orange-Nassau, whose royal family continues to rule the Netherlands today. One member of the family became King William III of England in 1689. Orange remained a Dutch possession more or less continuously until the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, under whose terms it was ceded to France.

So much history and clambering around the Roman ruins made us ready for lunch. We had no idea which restaurant to choose in the centre of Orange. My wife had the bright idea of entering one of the local shops, a shoe store, to ask where its workers went to eat their midday meal. They told us about a small restaurant around the corner. This busy eatery had a name which brought to mind associations with the American Wild West, ‘Le Buffalo West’, or something similar. It was a good recommendation and the food it served was excellent quality, reasonably priced French fare.

After a decent meal, we drove to a parking plot near a Roman triumphal arch. To enter the parking area, one had to drive below an arch designed to keep out large vehicles, and then down a steep ramp. Unfortunately, I turned the steering well before the car was fully off the ramp. We became grounded on a large concrete rock. The engine cut-out. I could not restart it. The car was well and truly stuck on the rock. Some people nearby saw our plight and told us that there was a repair garage a few yards away. We walked there.

The garage people sent out a team with a tow truck. Sadly, the truck was too high to pass beneath the height-restricting arch. Seeing the problem, three garage employees set to work with spades to dig around the rock on which our Saab was marooned. After at least an hour and a half’s hard toil in the baking afternoon heat, they removed the boulder and thus freed the car. Then, they pushed it beneath the arch so that it could be attached to the towing truck.

Raised on a ramp, it was easy to see where the rock had ruptured the Saab’s fuel line. It did not take the engineers long to replace the fractured section. Luckily, little other damage was visible beneath our car. Finally, we were ready to leave. It was with some anticipation that I asked to settle the bill. Imagining how expensive this labour-intensive episode would have been in the UK, I was expecting a bill of at least £300. So, I was not surprised when I was asked for about 300 French Francs. Then, a moment later, I could not believe my luck. A quick calculation had revealed that I was being asked not for £300, but for the Franc equivalent of about one tenth of this amount.

We returned to our gite, highly relieved that the car was back in service so quickly. That evening, as the sun set, we sat outdoors and enjoyed glasses of the local rosé wine whilst the charcoal on our barbecue began to reach the glowing stage that is best for grilling the meat that we had bought in one of the local markets.

The Saab remained in use for several more years but, to the surprise of our local dealer who serviced it annually, it began developing ominous cracks in its chassis. It was providential that these did not develop immediately after my driving misjudgement in that car park in Orange.

March 14, 2021

Philosopher’s stone and UFOs

A SCULPTED STONE stands in a small garden on the north side of All Saints Church in London’s Notting Hill. We have walked past it often during the various ‘lockdowns’ and over many years before these were deemed necessary, always remarking on its satisfying appearance but without questioning its significance. Yesterday, the 8th of March 2021, we entered the garden and examined the abstract stone artwork. It stands on a circular stone base inscribed with the words we had never noticed before:

“JOHN MICHELL 1933 _ 2009 WRITER GEOMETER NATURAL PHILOSOPHER”

By chance, the church was open, and we entered. There, we met one of its clerics and asked him whether the word ‘geometer’ meant anything to him. Like us, he had no idea about that or about Mitchell. My curiosity was aroused. There is plenty about John Michell on the Internet, but to a simple-minded chap like me, it is mostly rather weird, but that will not prevent me having a stab at trying to unravel why he was worth commemorating with a stone in Notting Hill.

Michell’s early life was conventional (www.john-michell-network.org/index.php/about-john-michell): educated at Eton and Trinity College Cambridge, where studied languages but missed examinations by oversleeping; trained as a Russian interpreter for the Royal Navy; painted and exhibited his works; and worked briefly as an estate agent and chartered surveyor. In 1966, by which time he had moved into one of the properties he managed in Notting Hill, its basement became the London Free School, an alternative community action education project (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Free_School). Around this time, Michell began publishing works on unidentified flying objects (‘UFOs’) and many other unexplained phenomena. His first book, “The Flying Saucer Vision”, published in 1967, was probably:

“… “the catalyst and helmsman” for the growing interest in UFOs among the hippie sector of the counter-culture.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Michell_(writer)).

This work introduced links between UFOs and ley lines, proposed by Alfred Watkins, (1855-1935), which some believe criss-cross the countryside and act as markers for extra-terrestrial spacecraft crewed by aliens who assisted human society early in the history of mankind. Along with two subsequent books, notably his “The View over Atlantis”, and other publications, Michell became an influential figure who believed in the:

“ “sacred geometry” of the Great Pyramid. Alfred Watkins’s ‘The Old Straight Track’ had come up with the concept of ley lines in 1925. John took it much further, believing that these alignments of traditional sites were a kind of feng shui of the landscape. They made up a sort of Druids’ transport system, he said, which harnessed a mysterious power that whisked large rocks across the countryside.” (www.theguardian.com/books/2009/may/06/john-michell-obituary)

As time went on, Michell delved deeper and deeper into phenomena like these. His knowledge of the hidden forces was used to help design the pyramid stage used at the Glastonbury Festival in 1971. It was because of him that Glastonbury an epicentre of New Age ideas and events (www.nytimes.com/2009/05/03/books/03mi...).

Unfamiliar as many of his ideas and theories are Michell was a serious thinker:

“His approach uniquely combined the thought of Plato and of Charles Fort. Blending scholarship and deep intuition, John often returned to his favourite subjects: Platonic idealism, sacred geometry, ancient metrology, leys and alignments, megaliths, astro-archaeology, strange phenomena, simulacra, crop circles, UFOs, the Shakespeare authorship controversy, and the nature of human belief.” (www.john-michell-network.org/index.php/about-john-michell)

You have heard of Plato, but Charles Fort (1874-1932) might be less familiar. This self-taught American researcher and writer, a contrarian, specialised in discovering and considering the many examples of phenomena that defied explanation by conventional (accepted) scientific methods and theories. When Michel wrote an introduction to one of Fort’s books, “Lo!”, he remarked:

“Fort, of course, made no attempt at defining a world-view, but the evidence he uncovered gave him an ‘acceptance’ of reality as something far more magical and subtly organized than is considered proper today.” (quoted in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Fort).

Not being inclined to philosophy, it would be unwise for me to attempt to explain how Michell’s ideas display the influences of both Plato and Fort.

Michell felt it necessary to question orthodoxy. His book on the identity of the true author(s) of Shakespeare’s plays, “Who Wrote Shakespeare?” examined this question thoroughly but received mixed reviews. Several of his other publications questioned the commonly accepted archaeologists’ interpretations of their findings, suggesting that their refusal to take ideas about ley lines seriously was a grave error. In the 1980s, two academic archaeologists investigated his ideas and found that he had erroneously included natural rocks and monuments that were created far later than during the prehistoric era as markers for his supposed ley lines. When the replacement of feet and inches by the Metric metre was introduced, Michell objected strongly to the abandonment of a measurement that he believed dated back to earliest times and established an Anti-Metrication Board to oppose the change.

Michell had one son, Jason Goodwin, born in 1964. His mother was the writer Jocasta Innes (1934-2013), who was married twice to Richard B Goodwin. Jason, a Byzantine scholar, is a well-known, prize-winning author, whose books my wife has enjoyed greatly.

Michell became a cult figure in Notting Hill, associated with the ‘local vibe’ and The Rolling Stones. He took members of the group to Stonehenge to scan the heavens for saucers (https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/03/books/03michell.html). He smoked marijuana regularly, publicly encouraged the use of mind-altering drugs, and, surprisingly, his favourite newspaper was the right-wing oriented “The Telegraph”. At Notting Hill, he lived at number 11 Powis Gardens, within easy reach of All Saints Church, where the stone monument to his memory can be found. It was sculpted by John de Pauley, who explained (www.constructingtheuniverse.com/JM%20...

“’The idea for the sculpture comes from Neolithic stone spheres. Their purpose remains a mystery. The geometrical construction is of a Platonic solid, 12 projecting tumescence making an icosahedron.”

Knowing this and a little about Michell, it seems an entirely suitable memorial to a bold and original thinker.

Finally, that word ‘geometer’: it is simply the name given to a mathematician, who studies geometry. One of Michell’s may paintings has the title “The Geometer’s Breakfast”.

March 13, 2021

Worlds apart

SOME ‘POSHER’ JEWISH people in west London tended to live around Bayswater. These prosperous members of the Jewish community arrived in Bayswater in the 19th century as the district began to be urbanised. Many of them had drifted westwards from Bloomsbury and the City (www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol9/pp264-265). This migration placed them at an inconvenient distance from the synagogues they had been used to attending. So, in 1863, Bayswater Synagogue (at corner of Chichester Place and Harrow Road) was consecrated. This new place of worship was a branch of both the of the Great Synagogue (in the City north of Aldgate) and the New Synagogue (originally near Leadenhall Street, and then later in Great St Helens Street). Like so many Jewish buildings in mainland Europe, this synagogue was destroyed by the forces of Nazi Germany, during WW2.

New West London Synagogue

New West London Synagogue In 1879, an offshoot of the now demolished Bayswater Synagogue was consecrated in St Petersburg Place, a short distance from the main road known as Bayswater. This, The New West End Synagogue, is now one of the oldest surviving functioning synagogues in Great Britain. At first sight, you might easily be mistaken for thinking that the huge red brick building with Victorian gothic architectural features, a rose window, and twin bell towers, is a church. And maybe that was the intention of the community that commissioned the building. Upwardly mobile Jewish people in Victorian England might well have preferred not to advertise their religious beliefs too much in a society that then had many prejudices against Judaism and other non-Christian religions. The synagogue in St Petersburg Place looks no more exotic or out of place than the Church of St Matthew a few yards north on the same street. In fact, it is another building to the north of these two and within sight of them that is unashamedly exotic in appearance, Aghia Sofia, the Greek Orthodox cathedral on Moscow Road, which was consecrated only three years after the synagogue.

The desire of some Jewish people to ‘meld’ seamlessly with British ‘high society’ was not confined to England. Amos Elon writes about this in his inciteful book about the ‘emancipation’ of Jews in Germany, “The Pity of it All”, and what a dreadful fate it led to. It is my impression that amongst the few Jewish people, mostly of British and German origin, living in Victorian South Africa, there was the belief that economic and social advancement was not hindered by being somewhat discreet about their religious beliefs. This changed during the final few decades of the 19th century when many Jewish people began arriving from parts of the former Russian Empire, many from what is now Lithuania. Often much poorer than their co-religionists, who were already well-established in South Africa, they were far less reticent about expressing their religious beliefs and critical of the ‘established’ Anglo-German Jewish community, who had, in their eyes, become rather too lax about Jewish religious observance.

Returning to Bayswater and its mainly prosperous Jewish families, we can now travel less than a mile northwest to reach the northern end of Kensington Park Road, close to Portobello Road, in nearby Notting Hill, to reach the site of another, now disused, synagogue. This building, still standing but now repurposed, was not designed to mislead the onlooker into believing it was a church. As was the case in South Africa during the last few decades of the Victorian era, large numbers of Jewish people began arriving in London from Eastern Europe, and many of them settled in the crowded East End. In 1902, A Jewish Dispersion Committee, set up by the (Jewish) banker and philanthropist Sir Samuel Montagu (1832-1911), tried to attract some of these new arrivals to settle in areas away from the East End, like Notting Hill (www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol1/pp149-151).

The former Notting Hill Synagogue at numbers 206/208 Kensington Park Road was opened in 1900 (www.jewishgen.org/jcr-uk/london/notting_fed/Index.htm), a little ahead of the formation of the above-mentioned committee. Presumably, it was worth opening because there must have been sufficient Jewish presence in the neighbourhood. By 1905, it had 281 members and ten years later, there were 250. Its ritual was Ashkenazi Orthodox, the same as that at the New West End Synagogue, but the congregants were less wealthy than those who attended the latter. Many of them were market stallholders or artisans, such as tailors and shoemakers (http://www.ladbrokeassociation.info/Churchesandotherreligiousbuildings.htm#Synagogue). They lived in what were at the beginning of the 20th century far less salubrious dwellings than many of those, who worshipped in St Peterburg Place. Although I do not know for certain, I doubt there was much socialising between the Jewish communities of Bayswater and Notting Hill.

The Notting Hill Synagogue was housed in a former church hall. Its memorial stone dated the 27th of January 1900 was laid by Sir Samuel Montagu. Although it was a discreet building externally, its interior with galleries for the women and girls was elaborate and attractive as can be seen in old photographs (www.jewishgen.org/jcr-uk/london/notti...). We have walked past it many times without realising it was once a place of worship until a friend told us recently about its former incarnation.

During WW2, the synagogue was severely damaged by a German bomb. It was restored and reconstructed. During the Notting Hill race riots in the late 1950’s, during the time that the fascist Oswald Mosely (1896-1980) was campaigning as a candidate in the election for the parliamentary seat of the local constituency, Kensington North, he set up his office close to the synagogue. On the 31st of January 1959, one of his supporters daubed the synagogue with the words used by the Nazis: “Juden raus”. Despite these traumatic events, the synagogue continued to thrive until the 1990s, when the size of the local Jewish population had declined. Rabbi Pini Dunner (born 1970), who had been invited to help in performing the ritual in 1992, when the synagogue, under the leadership of its charismatic Stuart Schama, was falling into decline, wrote:

“Notting Hill Synagogue was nothing like any shul I had ever seen. The congregants consisted of a motley group of mainly octogenarian men, characters out of some East End Jewish sit-com, each with his own catchphrase, many of them not quite sure why they were there week after week.”

(https://rabbidunner.com/memories-of-stuart-schama/).

The synagogue then closed, and amalgamated with the Shepherd’s Bush, Fulham & District Synagogue. Since its closure, the synagogue has been used as a ‘health club’. Currently (March 2021), the building bears the name ‘Teresa Tarmey’, a company that supplies various treatments (www.teresatarmey.com/).

The transformation of the former synagogue into a trendy beauty salon reflects that of Notting Hill from a relatively impoverished area into a prosperous area with high property prices, which is beginning to make Bayswater seem less attractive in comparison. The synagogue in St Petersburg Place continues to thrive. One of my cousins, who lives many miles from it, told me that it was well worth travelling to because its congregation is vibrant and life-enhancing, which is good to know because the mainly residential area surrounding the synagogue is usually rather sleepy.

March 12, 2021

Hampstead, Highgate, and the Indian freedom struggle

A MOTHER OF FAMILY-planning and women’s rights, Marie Stopes (1880-1958) lived at number 14 in Hampstead’s Well Walk between 1909 and 1916. I remember seeing a plaque recording her residence in Hampstead. However, I do not recall seeing the plaque to one of her neighbours, the socialist Henry Hyndman (1842-1921) on number 14. It was only when I acquired a copy of an excellent guide to Hampstead, “Hampstead: London Hill Town” by Ian Norrie, the owner of the former Hampstead book shop, ‘High Hill Books’ and Doris Bohm that I discovered that Hyndman had lived and died in Well Walk. Hyndman, a politician, lawyer, and skilled cricketer, was initially of conservative persuasion but moved over to socialism after reading “The Communist Manifesto”, written by Karl Marx in 1848. Although anti-Semitic, he was amongst the first to promote the writings of the (Jewish) Marx in England.

Replica of Highgate’s former India House in Mandvi, India

Replica of Highgate’s former India House in Mandvi, IndiaIt is an extremely pleasant walk from Well Walk, across Hampstead Heath, Kenwood, and through Highgate village to Highgate Wood, opposite which the Indian born barrister Shyamji Krishnavarma (1857-1930) lived in self-imposed exile with his wife Banumati. Born during the year when The Indian Rebellion of 1857 (First Indian War of Independence or ‘Indian Mutiny’) commenced, it seems that it was appropriate that he was a keen promoter of India being liberated from the British Empire. Krishnavarma, in common with Hyndman, believed that it was wrong that the British should control and exploit the inhabitants of India. They corresponded and most probably met each other.

In 1905, responding to events in India such as the unpopular partition of Bengal, Krishnavarma, a wealthy man, decided it was time to do something about bringing down the British in India. He did three main things. He began publishing a virulently anti-colonial newspaper, “The Indian Sociologist”; he gave money to create scholarships for Indian graduates to study in England; he bought a large house in Cromwell Avenue, Highgate. He was also one of the founders of the Indian Home Rule Society, whose views were in stark contrast to those of the Indian National Congress, which at that time, put great faith in the supposed benevolence of the British Empire towards its Indian subjects.

The scholarships had several conditions attached. The most important of these was that the recipients had to promise that they would never ever work for, or accept posts from, the British Empire. The candidates for these scholarships were usually recommended by people in India, such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who were working actively to end British Rule.

Krishnavarma, recognising that many Indian students faced considerable hostility in Britain at the start of the 20th century, used the house he bought in Cromwell Avenue to create both student accommodation and a community centre, a home away from home for Indian students in England. He called the building ‘India House’, which should not be confused with the better-known India House in Aldwych, the Indian High Commission.

The grand opening of India House in Highgate was on the 1st of July 1905. The inauguration speech was given by Henry Hyndman. I do not know whether he was already living at Well Walk when he opened the student centre in Cromwell Avenue.

Soon after it opened, India House became an important centre of anti-British activity. Under Krishnavarma’s leadership, and given his anti-colonialist views, India House became of increasing interest to the British police and intelligence agencies. In 1906. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar (1883-1966), a law student and leader of a secret revolutionary society, became a recipient of one of Krishnavarma’s scholarships. He lived in India House, where he wrote a couple of anti-British books, which were banned in British India. In brief, believing in armed revolution, Savarkar became one of the most dangerously anti-British activists in Europe. When Krishnavarma and his wife shifted to Paris in 1907, Savarkar became the ‘head’ of India House. Under his watch, smuggling of arms and proscribed literature to India was carried out. He encouraged experimentation in bomb-making, and was not dismayed when one of his fellow house-mates, Madan Lal Dhingra, assassinated a top colonial official in South Kensington in 1909. The assassination led to increased police surveillance and India House, which had been opened by Hyndman, closed by 1910.

I have introduced you to this lesser-known aspect of the history of the Indian Freedom Movement for two reasons. One is to explain my delight in discovering that I must have walked many times past the house in Well Walk where Hyndman lived (and died). For me, Hyndman has assumed greater interest than his deservedly far better-known neighbour Marie Stopes. The reason for this is that about five years ago I was in the town of Mandvi in Kutch (part of India’s Gujarat State). Krishnvarma was born in Mandvi and is now commemorated there. Apart from the modest house in which he was born, there is an unexpected surprise on the edge of the town. It is a modern replica of the Victorian house in Cromwell Avenue (Highgate), which was briefly home to Krishnavarma’s India House. Seeing this extraordinary replica of the house inaugurated by Hyndman in a flat desert setting got me into researching its story. In the end, I published a book about the Indian freedom fighters in Edwardian London, “Indian Freedom Fighters in London (1905-1910)”, which explores the story I have outlined in far more detail.

[“Indian Freedom Fighters in London (1905-1910)” by Adam Yamey is available from amazon, bookdepository.com, lulu.com, and on kindle. Or specially ordered from a bookshop: ISBN 9780244270711]

March 11, 2021

Stepping on history

INDUSTRIAL ACTIVITY IS NOT what one would associate with present-day Notting Hill Gate in London’s Kensington district. About the only thing that is made on a large scale in the ‘Gate’ is food, which currently is only available on a take-away basis. Yet, walking along the pavements in the area, you can see evidence that once upon a time the area was not devoid of industry. This is in the form of circular cast-iron coalhole covers. These metal discs that are almost flush with the pavement could be removed to provide an orifice through which coal could be supplied to the coal cellars beneath the pavement. Using these holes, the coal deliverers, usually covered with coal dust, could avoid entering the house. Many stretches of pavement have been re-paved, omitting the covers, because many of the former coal cellars have been converted to usable living space. The covers that remain – and there are still plenty of them – are often covered with patterns in bas-relief and bear the names and locations of the companies that manufactured them.

I was intrigued by one company, which made many of the covers in Notting Hill Gate, ‘RH & J Pearsons’ whose covers bear the words “Automatic Action” and the information that company was in Notting Hill Gate. I wondered where their factory was in the area, which is no longer associated with trades such as casting iron coalhole covers. I thought that there would be little information about this, but I was wrong. I shall try to condense some of the sea of informative material about these metal discs, over which we walk often without noticing them.

The company Robert Henry and Jonathan Pearson, which operated between the 1840s and 1940, was located at the following places at various times:

“Nos. 141 and 143, High-street, Notting-hill, Middlesex (1871) …and 91, 95, and 97 Camden Hill Road; Iron, Steel & Metal Warehouses, 21, 22, & 23 Upper Uxbridge St.; Manufactory & Workshops, 14, Durham Place, Notting Hill Gate, W. (1879) 141, 143, 145, High Street, Notting Hill Gate, London, W. (1901)” (https://glassian.org/Prism/Pearson/index.html)

All of these places are in Notting hill Gate.

In addition to coalhole covers, the company, which described itself as ‘manufacturing and retail ironmongers’, manufactured a wide range of ironmongery for domestic use including, for example, kitchen ranges, grates, fireplaces, railings, gates. They also produced electrical fittings (for lighting and cooking) and gas fittings. In addition, they supplied a wide selection of plumbing material and sanitary appliances.

Robert Pearson lived between about 1821 and 1893. His brother Jonathan lived between about 1831 and 1898. Both died in Newcastle-on-Tyne, where they were born (https://glassian.org/Prism/Pearson/index.html). Their father, William, was a hardware manufacturer. According to the 1861 England Census, both brothers were living in Kensington. The 1871 Census entry for Robert reveals a little about the size of the firm:

“Ironmonger, Senior Partner in the firm of R. H. & J. Pearson … employing 66 men”

So, Pearson’s was a large local business.

A document published by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea gives an insight to the manufacturing of coalhole covers (‘plates’):

“Skilled artisans were employed to design and carve wooden patterns of the required shape and size. From these an endless number of moulds were produced by ramming sand around them in a box called a flask. The pattern was then removed and molten metal was poured into the cavity. Sadly many examples of Victorian cast iron work has disappeared with the exception of street furniture, in particular coal plates.”

(file:///C:/Users/adama/Downloads/07%20-%20Grouped%20Pieces%20and%20Miscellaneous.pdf).

Of Pearson’s, the document adds:

“R H & J Pearson and Sons in Notting Hill Gate was one of the largest wholesale and retail ironmongers in the area and their name appears on countless plates. Robert Henry Pearson established his business in the 1840s and by the year of his death in 1893, 200 people were employed by the firm.”

One other bit of information about Pearson’s relates to one of its employees, John Henry Mills (1880-1942), who was born in Notting Hill Gate. On the 11th of November 1895, he was ‘bound’ to Pearson’s to serve an apprenticeship for five years. By late January1899, he had already run away and enrolled with 5th Rifle Brigade (London). For committing some now unknown felony, John was discharged on the 21st of March 1899. Soon after this the Second Anglo-Boer War broke out in South Africa. John served with the Imperial Yeomanry during this conflict. After the war, his movements are unknown, but he is known to have served in WW1. After marrying in 1918, he and his wife lived in London, where by 1939, he was recorded on an official register as a “housekeeper”. (www.bansteadhistory.com/BEECHHOLME/Beechholme%20Boer%20War/Boer_War_M.html)

Clearly, ironmongery had little appeal for young Mills.

Pearson’s made many of the coalhole covers in Notting Hill Gate, but by no means all of them. It is worth glancing occasionally at the pavement to see the variety of coalhole covers still in existence. It appears that some of these once mundane items are stolen, to be sold to collectors. Some of the stolen covers have been replaced by artistic modern covers. A good example is one with poetry on it near The Gate Cinema. Now redundant because coal is hardly used for domestic purposes in London, these metal discs are remnants of an era now fading ever further into history.