Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 114

September 8, 2022

A French corner in London

A COLOURFUL FABRIC artwork, a tapestry, by the artist Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979) hangs on a wall overlooking the grand staircase at the Institut français (‘IF’) in London’s South Kensington. Born in Odessa (Russian Empire) as Sarah Elievna Shtern, she spent most of her working life in Paris (France) after having studied art in both Russia and Germany.

Sonia Delaunay at Institut Francais in London

Sonia Delaunay at Institut Francais in LondonThe stairs lead from the ground floor to the first. It is at this level that the IF’s main and biggest cinema, the Ciné Lumière 1, is located. This airy cinema has rows of comfortable seats each with enough legroom to satisfy even the tallest person. We had come (on the 3rd of September 2022) to watch a Spanish film called “Official Competition”, starring amongst others Penelope Cruz. Frankly, I found this much-hyped film dull, disappointing, and somewhat puerile. The plot revolves around filmmaking and competing egos. The audience is treated to too much philosophising (actually, navel contemplating) about acting and moviemaking, the content of which would be considered almost infantile by high school children. However, the cinema’s comfortable seating made watching the film almost bearable. In the past, we have seen far better films at the Lumière, to which we will return to see other films in the future.

Apart from the poor film, the visit to the IF was fun. It was great seeing the Delaunay and we enjoyed cool drinks in the pleasant Café Tangerine on the ground floor.

September 7, 2022

A pretty perambulation

LONDON’S KENSINGTON GARDENS is bounded to the north by Bayswater Road and to the south by Kensington Gore (overlooked by the Royal Albert Hall and the Albert Memorial), which becomes Kensington Road. Within the park and running almost parallel with its southern boundary is the South Flower Walk (also known as The Flower Walk). The Northern Flower Walk, which runs near and parallel to Bayswater Road was once used by royalty. According to a document published on the Royal Parks website, this was:

“… a delicious and appealing place to stroll for the monarch on the way to … the site of the Bayswater ‘Breakfasting House’…”

The breakfasting house no longer exists. I am not sure whether the South Flower Walk can boast of such an illustrious past. However, when it is in full bloom, it outdoes its northern counterpart in colourfulness and variety of its flora.

Although the whole of Kensington Gardens makes for a pleasant place to stroll, a walk along the South Flower Walk provides and exceedingly pretty perambulation.

September 6, 2022

Macchiavelli and spicy masala meat dishes

RAAVI KEBAB BEGAN serving Pakistani and Punjabi food in the mid-1970s. It is located on Drummond Street, close to London’s Euston Station. This unpretentious eatery with barely any internal decoration except some mirrors with Koranic verses engraved on them in Urdu script, is next door to the Diwana Bhel Poori House. It was at the latter that we used to enjoy Indian vegetarian dishes when we were undergraduate students at nearby University College London during the first years of the 1970s. In those days, Raavi, named after the river that flows through the now Pakistani city of Lahore, did not yet exist. It was only in the early 1990s that a friend visiting from Bombay suggested that we ate with him at Raavi’s. When the grilled kebabs arrived at our table, it was love at first bite. We have been returning to Raavi’s ever since.

Raavi’s with Diwana in the backround

Raavi’s with Diwana in the backroundYesterday (1st of September 2022), we made yet another visit to Raavi’s. As we sat down, I noticed a thick wad of photocopies held together with a bulldog clip. They were resting on top of a neatly folded shawl. Out of curiosity, I looked at the top sheet, which was a page copied from a book with annotations added in red ink. I looked more carefully and noticed that the printed text was in Italian. The page was headed “ Joanni Folci Niccolaus Maclavellus”. It is a chapter (‘The ingratitude of Joanni Folci’) from a book by Niccolò Machiavelli (aka Maclavellus), who lived from 1469 to 1527. The rest of the text on the photocopied page appeared to be a learned commentary on Macchiavelli’s chapter.

I do not know why, but I felt that Raavi’s was the last place I would expect to find scholarly papers lying about so casually. I associate the place, as do most of its many customers, with grilled meat and spicy masalas. I asked the waiter about the papers. He shrugged his shoulders and said that someone must have left them behind after eating, and that he had no idea whether anyone would return to retrieve them.

September 5, 2022

Victorian gothic

September 4, 2022

Surprising Art Deco in a north London suburb

HAMPSTEAD GARDEN SUBURB (‘HGS’) in north London, where I spent my childhood and early adulthood, is a conservation area containing residential buildings designed in a wide variety of architectural styles. It first buildings were finished in about 1904/5. Despite this, many of the suburb’s houses and blocks of flats were designed to evoke traditional village architecture. Much of HGS contains buildings that do not reflect the modern trends being developed during the early 20th century, However, there are a few exceptions. These include some houses built in the ‘moderne’ form of the Art Deco style, which had its heyday between the two World Wars.

In Lytton Close

In Lytton CloseA few Art Deco houses can be found in Kingsley Close near the Market Place (see https://adam-yamey-writes.com/2022/02/07/art-deco-in-a-north-london-suburb/), and there is a larger number of them in the area through which the following roads run: Neville Drive, Spencer Drive, Carlyle Close, Holne Chase, Rowan Walk, and Lytton Close. The part of HGS in which these roads run was developed from about 1927 onwards, mainly between 1935 and 1938. So, it is unsurprising that examples of what was then fashionable in architecture can be found in this part of the suburb. According to an informative document (www.hgstrust.org/documents/area-13-holne-chase-norrice-lea.pdf) about this part of HGS:

“… A relatively restricted group of established architects undertook much development such as M. De Metz, G. B. Drury and F. Reekie, Welch, Cachemaille-Day and Lander, and J. Oliphant. H. Meckhonik was a developer/builder and architects in his office may have designed houses attributed to him.”

Most of the Art Deco houses on Spencer Drive and Carlyle Close leading off from it are unexceptional buildings, whose principal Art Deco features are the metal framed windows (made by the Crittall company) with some curved panes of glass. Fitted with any other design of windows, these houses would lose their Art Deco appearances. Number 1, Neville Drive displays more features of the style than the houses in Spencer Drive and Carlyle Close. There is, however, one house on Spencer Drive that is unmistakably ‘moderne’: it is number 28 built in 1934 without reference to tradition. It is an adventurous design compared with the other buildings in the street.

Numbers 13 and 24 Rowan Walk, a pair of almost identical buildings which stand on either side of the northern end of the street, where it meets Linden Lea, stand out from the crowd. They have flat roofs and ‘moderne’ style Crittall Windows. Built in the 1930s, they are cubic in form: unusual rather than elegant.

I have saved the best for last: Lytton Close. This short cul-de-sac is a wonderful ensemble of Art Deco houses with balconies that resemble the deck railings of oceanic liners, flat roofs that serve as sun decks, curved Crittall windows, and glazed towers housing staircases. Built in 1935, they were designed by CG Winburne. I have to admit that although I lived for almost three decades in HGS, and used to walk around it a great deal, somehow I missed seeing Lytton Close (until August 2022) and what is surely one of London’s finer examples of modern domestic architecture constructed between the two world wars. Although most of the Art Deco buildings in HGS are not as spectacular as edifices made in this style in Lytton Close and further afield in, say, Bombay, the employment of this distinctive style injects a little modernity in an area populated with 20th century buildings that attempt to create a village atmosphere typical of earlier times. The architects, who adopted backward-looking styles, did this to create the illusion that dwellers in the HGS would not be living on the doorstep of a big city but instead far away in a rural arcadia.

September 3, 2022

Walter and the woodlice at Whiteleys

Painted by Walter Sickert

Painted by Walter SickertAT THE TATE Britain, I visited the exhibition of paintings and drawings by the artist Walter Sickert (1860-1942). Amongst these, I was interested to see one which depicts a stretch of the platform at what is now Bayswater Underground station. In Sickert’s time, this station was called ‘Queens Road (Bayswater)’. Painted in 1914-15, this station was the closest one to his then home in Kildare Gardens (off Westbourne Grove). In the painting there is a man seated on a bench beneath an advertisement for Whiteleys. This was a department store, whose history I have described in my book “Beyond Marylebone and Mayfair: Exploring West London”*. Here is a shortened extract:

“Queensway was the home of a large department store called Whiteleys. Created in nearby Westbourne Grove by William Whiteley (1831-1907) in 1863, it moved into its large home on Queensway in 1911. After going through various transformations over the years, eventually becoming a shopping mall with restaurants and a cinema, it closed in 2018 … Since 2018, developers have removed the building’s innards whilst preserving its outer walls. The aim is to create a new shopping area along with a hotel and residential units. The final product might be interesting as its architects are from the team led by Norman Foster.”

Between 1968 and 1970, I was at north London’s Highgate School studying in preparation for my A-Levels (examinations to gain admission to university). One of my subjects was biology. I decided to enter the school’s Bodkin Prize biology essay competition. For some long-forgotten reason, I chose as my essay topic the life of woodlice. Seeing the above-mentioned painting by Sickert, reminded me of this essay. Being a keen researcher, even in my late teens, I discovered that there was a detailed book on my chosen subject, and this was available for perusal in a science library (the National Reference Library for Science and Invention), which was part of what has now become known as The British Library. In the late 1960s, when I required the book, the library’s collection was housed in a part of what had been the former Whiteleys department store on Queensway. It was a peculiar place: the bookshelves and readers’ desks were arranged on several layers of curved galleries surrounding a circular open space on the ground floor. Above the circular space, there was a spectacular, circular, large diameter, glazed skylight. The book I consulted was in French, and I spent a whole day laboriously translating it and making notes for use later. ‘cloporte’ is the French for ‘woodlouse’, just in case you are wondering. I believe that one visit was sufficient for me to collect what information I needed.

In December 1967, there was a debate about the state of the British Museum Library (now British Library) in the House of Lords. During a long speech, Viscount Eccles (1904-1999) mentioned the library where I had read about woodlice:

“Learned societies and famous men in the arts and the sciences have been shocked by the substance and the manner of the Government’s decision concerning the Library … An example of how the Act works can be seen in what has happened to the National Reference Library for Science and Invention. For years the former Trustees were frustrated by the delays and niggardliness of previous Governments in finding accommodation for this growing section of scientific material, not to mention the disgraceful shilly-shallying over the Patent Office Library. The position grew so desperate that the Trustees decided to gather together part of the material in temporary premises in Bayswater—admittedly very unsatisfactory…” (https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1967/dec/13/british-museum-library)

I visited the library a year or so after that speech. As for my essay, I won 2nd prize: 15 shillings (75pence) to spend on books, which was reasonably generous at that time. 2nd prize might impress you for a moment until I reveal that I was one of only two entrants. The 1st prize was won by my classmate Timothy Clarke. His older brother, Charles Clarke, not only became Head of School but later served as British Home Secretary between 2004 and 2006.

Returning to Whiteleys, I began visiting it regularly after 1993, when I began living nearby. Then, as described already, it had become a shopping mall. The galleries, which had once served as a library, were lined with shops and eateries, as well as a cinema. But that is all in the past, and what was once Whiteleys is now a building site. I doubt that Sickert would have been pleased if he were able to see it today.

* My book is available from Amazon:

September 2, 2022

Throwing light into the darkness and shadows

FOR UNKNOWN REASONS, we were initially reluctant to bother with viewing the exhibition (at London’s Tate Britain until the 18th of September 2022) of paintings and drawings by Walter Sickert (1862-1942). However, I am glad that we did because we got to know and appreciate an artist, of whom I had heard but knew little about. That little which I did know was that for a brief while Sickert had one of the Mall Studios in Hampstead, where years later the sculptor Barbara Hepworth worked and resided with one husband, and then another. Later, Sickert moved from Hampstead to Camden Town.

Sickert was born in Munich (Germany). He and his family moved to Britain when he was 8 years old. His father, Oswald Sickert (1828-1885), an artist, introduced him to the works of important British and French artists, but Walter’s inclinations led him to study acting. However, in 1882 he entered London’s Slade School of Art (at UCL) and he became a student and assistant of the artist James Abbott McNeil Whistler (1834-1903). Soon, he began spending a lot of time in France, where he met Edgar Degas (1834-1917), whose work was to have a great influence on his style.

The exhibition at Tate Britain successfully demonstrates that Sickert was a highly competent artist. His topographical paintings (notably of Dieppe and Venice) are superb, as are the many of his portraits, some of which verge on being impressionistic, on display. His depictions of scenes within theatre show his great ability to portray light and shade. A series of paintings of nude women, some of whom are shown being in the company of often disinterested-looking men in far from elegant clothing, throw light on the shady world of the poor in places such as Camden Town and its environs.

Although some of Sickert’s paintings show features that later would become associated with artists such as the impressionists, Lucien Freud, and Francis Bacon, he is not one of the first artists that springs to mind when thinking about the great artists of the late 19th and early 20th century. Why is this the case? Despite hinting at what was to become common in the works of the Abstractionists, he never broke through the barrier into Modernism as did painters such as Braque, Picasso, Miro, Kandinsky, Matisse, and Mondrian. In no way does this detract from the brilliance seen in Sickert’s work. In a way, he was born too late to be considered as distinguished as those I have mentioned. Considered alongside 19th century artists, he shines. But, although he received many commissions, he was painting during an era when the more adventurous and innovative artists were in their heyday. That said, I can strongly recommend the exhibition at the Tate, which demonstrated to me that Sickert, a master of light and shade, was an artist who deserves much more attention than he gets today.

September 1, 2022

No park like this in New York City

MOUNT STREET GARDENS in London’s Mayfair was formerly the burial ground of St George’s Church in Hanover Square. Its name derives from Mount Field, where there had been some fortifications during the English Civil War. The burial ground was closed in 1854 for reasons of protecting public health. St George’s Church moved its burials to a location on Bayswater Road, St Georges Fields, which is described in my book “Beyond Marylebone and Mayfair: Exploring West London”. In 1889-90, part of the land in which the former burial garden was located became developed as the slender park known as Mount Street Gardens (‘MSG’- not to be confused with a certain food additive). Small as it is and almost entirely enclosed by nearby buildings, it is a lovely, peaceful open space with plenty of trees and other plants.

The garden is literally filled with wooden benches. Unlike in other London parks where there is often plenty of space between neighbouring benches, there are no gaps more than a few inches between the neighbouring benches in MSG. The ends of neighbouring benches almost touch each other. The result is that MSG contains an enormous number of benches given its small area. And they are much appreciated by the people who come into the park and rest upon them.

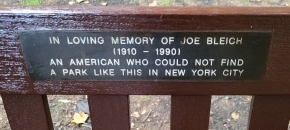

Each bench bears a memorial plaque. Many of these memorials commemorate people from the USA, who have enjoyed experiencing the MSG. And most of these having touching messages written on them. Here are just a few examples: “For my children Philippa and Richard, young Americans who may one day come to know this place. Richard L Feigen. 8th August 1987”; “Seymour Augenbraun – a New Yorker and artist for whom this spot in London is his oasis of beauty. From his wife Arlene and family on July 15th 1986”; “To honour a dear brother and sister Ira and Nancy Koger of Jacksonville Florida”; “This seat was given by Leonora Hornblow, an American, who loves this quiet garden”; “In memory of Frances Reiley Bochroch, a Philadelphia lady who found these gardens a pleasant pace”; and “In loving memory of Joe Bleich (1910-1990). An American who could not find a park like this in New York City,”

There are plenty of other similar memorials to Americans on the benches. All of them interested me, but one of them particularly stood out: “To commemorate Alfred Clark, pioneer of the development of the gramophone. A friend of Britain, who lived in Mount Street”. Clark (1873-1950) was a pioneer in both cinematography and sound recording. Eventually, he became Chairman of EMI. A keen collector of antique ceramics, he donated some of his pieces to London’s British Museum.

Not all of the benches are memorials to Americans. There are others to Brits and people from other countries, but the Americans outnumber the rest. Had it not been for the extraordinarily large number of benches in this tiny gem of a park, I doubt that my eye would have been drawn to the commemorative plaques, but having seen the one in memory of Joe Bleich, who was unable to find a park like it in NYC, I was drawn to examine many of the others.

August 31, 2022

Americans in Mayfair

MY UNCLE SVEN Rindl (1921-2007) was a structural engineer. He was involved in the construction of the building on the west side of Mayfair’s Grosvenor Square, which used to house the Embassy of the USA until recently. About yards south of the former embassy building, there is another place associated with the USA on South Audley Street. Far older than the embassy, this is the Grosvenor Chapel, whose foundation stone was laid in 1730 by Sir Richard Grosvenor (1689-1732), the local landowner. The relatively simple brick and stone church with some neo-classical features was ready for use in 1731. When the church’s 99-year lease ran out in 1829, it became adopted as a chapel-of-ease (i.e., a chapel or church within a parish, other than the parish church) to St George’s Hanover Square.

Until very recently, I had often passed the Grosvenor Chapel when going to and from The Nehru Centre, also on South Audley Street, but had never entered it. Yesterday (26th of August 2022), the doors were open and, being early for a dance performance at the Nehru Centre, I looked inside the chapel. Its interior is simply decorated. The wide nave lies below a barrel-vaulted, plastered ceiling. Galleries supported by columns with Ionic capitals flank the north and south sides of the nave. The chancel is separated from the nave by a screen with openings, each of which is flanked by pairs of Ionic columns. The screen was added by the architect John Ninian Comper (1864-1960) when he remodelled the church’s interior in 1912.Ionic columns with their bases on the gallery support the ceiling of the nave. Windows (with plain glass panes) on two levels, both below and above the galleries, give the chapel good natural illumination. In summary, the simple, white-painted chapel, though not large, feels spacious. Its simplicity is a complete contrast to its neighbour, the flamboyant Gothic Revival style Catholic Church of the Immaculate Conception.

An inscribed stone plaque on the west front of the chapel records its American connection. The words on it are:

“In this chapel the Armed Forces of the United States of America held Divine Service during the Great War of 1939 to 1945 and gave thanks to God for the Victory of the Allies”

The American General Dwight David Eisenhower (1890-1969) was amongst those who worshipped there during WW2. Many years before that, another person connected with the USA, John Wilkes (1725-1797) was buried in the chapel. Wilkes, a radical journalist and politician, was a supporter of the American rebels during the American War of Independence.

America (i.e., the USA) has been associated with Mayfair since it gained independence from the British. Its first embassy was in a house in Mayfair belonging to John Adams (1735-1786), who was the first US Minister to the Court of St James (between 1785 and 1788). The embassy’s Chancery moved several times before 1938, when it was housed in 1 Grosvenor Square, now the home of the Canadian High Commission. Thus, during WW2, it was close to the Grosvenor Chapel. The embassy building, in whose construction my uncle was involved, was designed by the architect Eero Saarinen (1910-1961), and completed in 1960. By January 2018, the embassy had shifted from Grosvenor Square to a newly constructed edifice across the Thames at Nine Elms.

Returning to the small chapel, a small note about its name. The place’s website (www.grosvenorchapel.org.uk) explained:

“It retains its title of Chapel because it is not, and never has been a parish church, and its continuing existence is entirely dependent upon the generosity of those who worship here regularly or visit from time to time.”