John Ironmonger's Blog, page 2

June 17, 2024

Announcing the Polish edition of 'The Whale at the End of the World' 17 June 2024

I'm excited to announce that my novel 'Not Forgetting the Whale' will launch today in Poland as 'Wieloryb i Koniec Swiata.' Thanks to the great team at Relacja. We've had fun this week filming bits for the trailer. Thanks to Sue who did some of the filming, and to Jenny and Graham who helped us find a great beach, and to Jon who filmed the pub scenes and stitched it all together. Here's the trailer ...

April 22, 2024

How many giraffes were on the ark? (and other musings) [22nd April 2024]

So how many giraffes do you thinkthere were on Noah’s ark? (By the way you don’t have to believe in Noah or his ark to answer this. It is a theoretical question. You only need some familiarity with the mythology.) I’masking because this is a question that pops up in my novella ‘The Year of theDugong’ and the answer sheds an interesting light on our knowledge (or lack ofit) of the natural world. Stay with me …

Start, if you can, by imagining an illustration ofNoah’s Ark – the kind you might find in a children’s book. Like the one I’musing here. An artist with this commission is ridiculously spoiled for choice. There are a millionor so animals available to populate the picture. But since most of those millioncreatures would be rather inappropriate for an ark – including fish, bugs,worms, and myriads of sea-creatures, let’s limit the scope to land mammals, reptiles,and flightless birds. This would offer around fifteen thousand pairs of animalsfor our illustrator to choose for the ark. Yet despite this, you may havenoticed, one pair of animals nearly always makes an appearance – giraffes. Norespectable ark is complete without them. Just two of them. But here is the thing. Two giraffes arenot enough. There are, you see, depending upon whom you ask, either four, six,or eight, or even nine different giraffes. Noah would have been remiss in hisduties if he didn’t take eighteen. You don’t often see eighteengiraffes on Noah Ark. But perhaps you should.

It might surprise you to learn that a giraffe is not alwaysa giraffe – or rather that two giraffes randomly admitted onto an ark might notnecessarily be the same. We are used to using the one word, ‘giraffe’ todescribe them all. But that’s our laziness or our ignorance, not a recognitionof reality. The four species most zoologists agree upon are the Masai giraffe, thenorthern giraffe, the reticulated giraffe (sometimes called the Somali giraffe),and the southern giraffe. It isn’t all that difficult to tell them apart. Thereticulated giraffe, for example, has a rather distinctive pattern. It doesn’thave spots. It has a kind of continuous, smooth, white line on a nutty brown, almostorange background, creating large and slightly irregular polygons, likesomething drawn by a graphic designer during a coffee break. The Masai giraffeis a whole lot darker, and its pattern is blotchy. It has smaller markings thatare sometimes described as ‘star shaped’ but are more like the kinds ofexplosion-shapes you get in comic books. The northern giraffe looks something likethe reticulated giraffe, but with smaller markings and a wider white line. Youcan spot a northern giraffe because its pattern ends at the knee (which is notstrictly a knee, but you know what I mean). The southern giraffe is lighter –often very pale – with spots on the lower legs.

And there could be more. There are zoologists out there whoinsist that the northern giraffe is not one species, but three; these peopleare cheerleaders for the Kordofan giraffe which lives in hard-to-get-to placeslike Chad and the Central African Republic, the Western giraffe (mostlyconfined to Niger), and the Nubian giraffe which lives in East Africa but isn’treally happy there. Equally the southern giraffe might be two species –theAngolan giraffe, and the South African giraffe. Which would give us eight.

This is all rather confusing, and somewhat unexpected. Thisis the Twenty First Century after all. Surely, we know how many species ofgiraffe there are? But no. It seems we don’t. The fact is, while zoologists canget very worked up about identifying species, giving them names, describingthem in guide-books and so on, nature itself tends to get on with things in amuch more messy way, content to leave the cataloguing up to us. Mostdictionaries define a ‘species’ broadly,or approximately, as ‘a group of livingorganisms consisting of similar individuals capable of interbreeding,’ andthis is an important definition because the idea of a species is a fundamentalconcept in biology, in the same way, perhaps, as an element is in chemistry, ora date is in history. A species should be something with hard boundaries, aboutwhich we can all agree. But take a look again at that definition. ‘Similar’ is a rather vague word to havein a dictionary definition. Is a reticulated giraffe similar to a Masai giraffe? Well yes. Tourists might see both inparts of Kenya and not be aware they’ve seen two different giraffes. But canthey interbreed? Now this is harder to establish. We know from studies of giraffegenes that the four species described above have not exchanged genetic materialfor over a million years. But this doesn’t mean they couldn’t. Maybe they havebeen separated geographically for so long they haven’t had the opportunity totry. Perhaps if Noah found two frisky, fecund giraffes – one reticulated andthe other, say, a Nubian – they might be persuaded to breed. This isn’t anexperiment we can readily carry out, and even if we could, there are powerfulethical arguments that would (and should) prevent us. But even if we were,somehow, to cross a Masai and a Nubian giraffe, it wouldn’t necessarily meanthey were the same species.

Consider the lion and the tiger. No one would dispute theseare different, very distinct species. Yet there exists an animal known as a‘liger’ which is the offspring of a female tiger and a male lion. (A ‘tigon’ isa similar thing where the parents are the other way around). Ligers and tigonsonly exist in captivity, and no evidence has ever been found that lions andtigers have ever interbred in the wild (even though their ranges cross in partsof India). We know from genetic studies that lions don’t have tiger genes, orvice versa. There was once an assumption that these liger and tigon hybrids wouldalways be infertile in the way that mules are (a mule is a cross between ahorse and a donkey), but this doesn’t seem to be the case. In 2012 a Siberianzoo successfully bred a ‘liliger’ which is the offspring of a lion and a liger.

So where does this leave us? Are lions and tigers the samespecies or not?

On 11th July 1978, shortly after nine in themorning, a 22 year old Asian elephant called Sheba, who had been behavingrather strangely, surprised her keepers at Chester Zoo in the north of England bydelivering a calf. The only bull elephant Sheba had encountered for well overtwo years had been a rather temperamental African elephant known as Jumbolinoor ‘Bubbles.’ No one had expected an Asian elephant and an African elephant tobe able to interbreed. The calf, called ‘Motty’ (after George Mottershead thefounder of Chester Zoo), had ears like an African elephant, but just one ‘trunkfinger’ like an Asian elephant. A day later the baby elephant was on his feetand bottle feeding, and within four days Sheba was feeding him normally. Sadlyhe didn’t survive very much longer. He died of septicaemia aged just ten days,but there is no reason to think he couldn’t have lived for very much longer –perhaps even a full elephant lifespan.

As you’d expect, these are by no means the only animalhybrids, or even the best known. The world of hybrid animals is characterisedby an apparent desire to mangle a name for the new creature out of the names ofthe parents. So we have zeedonks(zebra and donkey), jaglions (jaguarand lion … although surely jagonswould be more conventional), grolar bears(grizzly bear and polar bear), and even camas(camel and llama). There was once a fashion for creating such animals, althoughmost zoos would look dimly on such an idea these days.

But perhaps the real surprise should not be that someanimals can be persuaded to interbreed, but rather that so few do, andespecially that this hardly ever happens without our encouragement. It seemsthat the word species might need abit more definition. Perhaps we should redefine it as ‘a group of living organisms consisting of similar individuals capableof interbreeding, and generally disinclined to breed with any other species.’

This is important because the whole idea of the species isso fundamental to zoology. So while we are about it, shall we dispose of someof the other words people often use when they try to talk about a species?Let’s kick off with breed. I can’ttell you how irritated it makes me when I hear someone call, say, a chimpanzee,a breed of monkey. To begin with achimp isn’t a monkey – it’s an ape. More importantly a breed is something we humanscreate. We breed dogs for hunting or for fetching or for pampering and theresulting specimens we call a breed – cocker spaniels, German shepherds, Frenchpoodles – these are all breeds. Throw them together and they would have nohesitation in creating all manner of cross breeds, and these are breeds toowhether or not they are recognised and named by the Kennel Club or anyone elsefor that matter. We have breeds of sheep, of cattle, of domestic cats, but wedon’t have breeds of giraffe or chimpanzees. While we’re on the subject ofbreeds, we could throw in varieties.I have heard this word used too when the speaker clearly meant species. You canhave varieties within a species. Some people have red hair, others are dark.Some giraffes are taller than others. Variety is the motor for evolution, butvarieties are not taxonomically significant – which is to say they don’t affectthe way we classify or name animals or plants. Variety is often used by breeders to describe variations within abreed, and they can be given names of their own – especially with plants. Anycompetent horticulturalist can create new varieties of say, roses, by selectingseeds with the characteristics they would like to see. Mix and match, and acouple of generations later, hey presto, a rose named after your grandmother.That’s a variety.

So having cleared that one up, let’s turn our attention to amuch more slippery word. In a park in Williamstown, Kentucky, about an hour’sdrive south of Cincinnati, you will find a very curious tourist attraction. Ark Encounter is a building designed tolook like … well, an ark, albeit an ark on land. Apparently built to thedimensions provided in the book of Genesis, it’s aim is to convince us thatNoah was a real historical figure and his ark was a proper boat, and that,guess what, he did indeed sail away in a flood with two of every kind ofanimal, and there on board to help prove the point are models of hundreds ofanimals including dinosaurs and even a couple of unicorns. But did you noticethe contentious word? Kind. This isthe word that enables Ark Encounter to get away without providing sixteen or eighteen giraffes, or six thousand snakes, or seven hundred thousand beetles. Theirwebsite explains it like this: “Speciesis a term used in the modern classification system. The Bible uses the term“kind.” The created kind was a much broader category than the modern term ofclassification, species.”

There. With a single judicious use of an ambiguous wordtranslated roughly by seventeenth century scholars in England from a seventhcentury Greek translation of a bronze age Hebrew manuscript, Ark Encounter areable to sweep away a thousand years of biological science. This is veryconvenient for creationists. They no longer have to house loads of giraffes onthe ark. Two will do. A website called ‘Answers in Genesis’ goes evenfurther; it argues that the giraffes on the ark not only became the ancestorsof all of today’s giraffes, but also of okapis, and a host of now extinctcreatures. (That sounds suspiciously like evolution to me but let’s not be tooprovocative.) The Answers in Genesis site goes as far as proving us with apicture of what the giraffes on the ark might have looked like. They label thepicture ‘Shansitherium.’

There is no point really trying to argue with this. Creationistswill believe what they want to believe. But can the rest of us please agreethat the word ‘kind’ does not belong in any discussion of taxonomy. And whilewe’re about it, can we dispose of another contentious word: race. Racemight once have been a useful (but informal) term in biology to describe agenetically distinct populations of individuals within the same species, but theword has become hijacked by disagreements within our own species, so I wouldsuggest we set it aside completely. Along with the word ‘strain.’ Theremay be races and strains of giraffes – there probably are – but I don’t imagineeven God expected Noah to collect every variation or every strain of giraffe onthe ark. If he had there wouldn’t have been room for anything else.

Now here’s another tricky word. Subspecies. The idea ofthe subspecies can feel like a rather helpful way for zoologists to avoidtoo many disagreements. We tend to call a group of animals a subspecies when wefind them in a different area with particular differences in size, shape, orother characteristics, even though we might suspect that the different subspeciescan probably interbreed. You might have read about the imminent extinction ofthe Northern white rhino. There are only two known individuals of thissubspecies still alive. Both are female, so sadly this is almost certainly the end for theNorthern white rhino. The two rhinos are called Najin and Fatu. They live in the OlPejeta Conservancy in Kenya where they are protected by armed guards. When theygo it will undoubtedly be a great loss. But there is a sense that the loss of asubspecies is less of a tragedy than the loss of a species. Northern andSouthern white rhinos have been living separately for at least half a millionyears, but the differences that are visible to us are subtle, and you wouldneed to be an expert in rhino morphology to confidently tell them apart. Theremay be other differences, of course, that are not visible, andthis might lead us to wonder if there are more rhino subspecies than the oneswe know. This could also be true of giraffes. Noah would surely have had quitea challenge to untangle this. But the key point for us, and for Noah is this: if you have two subspecies that haven't interbred for half a million years, you do need to put both on the ark. Sorry. Remember that according to Bishop Ussher the flood that floated the ark was in 2,349 BC, just 4,373 years ago - a blink of an eye in evolutionary terms. (Not really long enough by the way for a giraffe to evolve into an okapi.) The IUCN (the International Union for theConservation of Nature) who are the arbiters of these things, officially recognises nine subspecies of giraffe. Herethey are in the illustration below (happily a royalty-free image: thank youAlamy).

So the answer to our original question (memo to Mr Noah) appearsto be eighteen giraffes. We have to hope the ceilings on the ark were high.

But there is afollow-on question. Why don’t we all know this? Why don't illustrators of the ark know this? Why isn’t this taught in schools?How is it that we can identify soccer strips and car marques and fashion logos but we canonly collectively identify one giraffe? We knowledgeably and assertively distinguishgrape varieties and wine labels and cheeses and breeds of dog, but if you ask one hundred peoplewhat species of rhinos still walk the earth, most, I fear, wouldn’t know. (There arefive, white rhinos, black rhinos, Indian rhinos, Javan rhinos, and Sumatranrhinos). Why does this matter? Well if we can’t tell animals apart, we won’t mourn them when we lose them. That is why this matters. As Toby Markham says in 'The Year of the Dugong:'

"Do you know how many moths there are in Suffolk? Howmany species? Probably over two thousand. And how many people do you thinkcould identify a single moth? Just one species?’ Toby raised a finger. Hepaused to look at the silent crowd. ‘I doubt if one person in a hundred coulddo that. So, if no one can identify even a single moth, how many people aregoing to notice if two thousand species of moths become one thousand? Or onehundred? How many people are really going to care?’

Natural history is becoming a dying art. That’s sad. I don't expect people to identify two thousand moths. But more people ought to know how many moths there are. Because if we don't care, then one by one they will surely go. And so will the Northern white rhino. And one day there may really only be a single species of giraffe. That's heartbreaking.

Check out my website: www.johnironmonger.com

February 29, 2024

The Wager and the Bear [Posted 29th Feb 2024]

It's leap-year day so I have an announcement. My climate-crisis novel, 'The Wager and the Bear,' is to be published by Fly on the Wall Books, a northern based publisher-with-a-conscience who specialise in books that might raise awareness of political or climate issues. I love this publisher very much and I can't think of a better home for 'The Wager and the Bear.' Do please follow me on social media for announcements closer to publication date, or check out my website https://www.johnironmonger.com/ and I'll let you know when it is ready to pre-order.

It isn't a heavy polemical novel. It's simply a good old adventure yarn and a romance but it is quite clearly set against the backdrop of a slow, unfolding global crisis. Oh ... and there is a bear ...

January 21, 2024

SOON TO BE A MAJOR MOTION PICTURE 21 Jan 2024

I don't want to jinx this because I know a lot of water has to flow under the bridge between the day you sign up with a studio and the day you buy a cinema ticket to see the finished film ... but all the same I can't resist this little teaser. This is probably all I'm allowed to reveal. Apart from saying that the team behind the movie are utterly awesome. But I will post updates whenever I can. Watch this space ...

November 20, 2023

One Step away from the Precipice: Climate Change in Fiction [Posted 20 Nov 2023]

This was my article yesterday in La Repubblica - Italy's biggest newspaper. The title translates as 'One Step from the Cliff' - and it is an artcle about climate change in fiction, and about my novel 'The Wager and the Bear' (Soon to be published in English I hope).

Here is the translation of the text:

David Bowie had a remarkabletalent for writing songs that could conjure up a story. It is impossible tolisten to ‘Space Oddity’ without imagining Major Tom, sitting in atin-can, drifting forever into space. But the Bowie song that stays with me most is ‘Five Years’. It tellsa very simple story. News has reached us that the earth has only five yearsleft. The planet is dying. In the song, the newsreader weeps. All around themarket square people lose their minds.

What would it be like, I haveoften wondered, if we really were told this news? If a solemn news report,backed by all the world’s serious scientists, was to tell us we were runningout of time? How would we react?

Well we now know theanswer to this question. Newsreaders wouldn’t weep. No one would go crazy. Wewould ignore the danger and carry on with our lives as if nothing had changed. Weknow this because this is what we do. Every few months the IntergovernmentalPanel on Climate Change (IPCC) produces a new report telling us the planet isrunning out of time. Every year the COP climate change conference makes direpredictions. Every year we learn that the previous year was the hottest onrecord. We watch forest fires in Canada and Brazil. We see dramatic floods,powerful storms, devastating droughts. We watch the collapse of animalpopulations. World leaders fly in and out of conferences. They make vaguepromises. But very little changes. And the world continues to die.

The challenge seems to bea failure of human imagination. Perhaps it is the timescale. If the world wasdoomed in just five years, we might be more alarmed. If it was an asteroid hurtlingtowards us, we might make a real global effort to find a solution. But climatechange seems to be a long unfolding tragedy. We are like passengers in aslow-motion train crash. The train is heading for a precipice, and all thepieces are in place for a terrible disaster, but everything is moving so slowlywe stop worrying.

All this presents aparticular problem for story tellers. Climate change is the biggest story ofour time, yet very few novelists are ready to grapple with this. Ten centuriesfrom now, if humanity is still around, I suspect historians will only beinterested in one story from our generation - how we responded (or failed torespond) to this existential threat to the planet. Science fiction, in general,has done us rather a disservice here. Writers have sold us either Mad Max-styledesert dystopias, or impossible tales of starships taking survivors to newgreen planets. What we don’t have are real world stories that could help us toimagine the kind of earth we are creating. And that is a shame, because imagination iswhat we need, now more than ever.

Once again, timescales seemto be the challenge. Novelists need a central protagonist with whom readers canidentify. This character needs to have a story arc, and human dramas aretypically too short for climate change to feature very much. There is a secondproblem too. It is hard to imagine anycharacter playing anything but a very minor role in what is a huge globaldrama. No one is going to step forward like Bruce Willis and save the world. Fora writer, that is an unhelpful backdrop. We do not like to set up a jeopardyfor our characters, without giving them some way to fight back. But how do youfight back against a warming planet?

In ‘L’Orso Polare e unaScomessa Chiamata Futuro’ (The Wager and the Bear) I hope I may have founda way to navigate a little around these two problems. The narrative unfoldsover a whole human lifetime, and the central characters are front-seatobservers of the climate disaster. The story involves two young men. One,Monty, is a politician. He is a climate change-denier. He lives in a grand houseon the beach in Cornwall. He has a splendid lifestyle, and like so many of usin the slow-motion train crash, he doesn’t see the precipice approaching. Thesecond man, Tom, is a climate scientist and campaigner. One drunken night, overtoo many glasses of cider in the local inn, the two men get into a quarrel. Itends with a deadly wager. In fifty years, either the sea will rise enough todrown Monty in his home, or Tom will accept the jeopardy himself, and will walkinto the sea and drown. A video of the wager, posted online, goes viral. Howwill it all work out?

Well we have fifty yearsfor the story to unfold. The lives of the two men cross several times, leadingthem both onto a melting glacier, and ultimately onto an iceberg floating downthe coast of Greenland where their only companion is a hungry bear.

The story is not entirelywithout hope. It is set against the backdrop of a campaign to restore some ofwhat the world has lost. Neither Monty nor Tom can save the world. But there isat least hope, as well as despair.

Climate change doesn’thave to be front and centre in contemporary fiction. But we shouldn’t beignoring it either. As writers we have a responsibility, sometimes, to make thefuture seem real. We are hurtling towards a world of human-made disasters, ofdying oceans, of rising seas, of failing harvests, of droughts, of economiccollapse, and of climate-driven conflicts. We cannot ignore these things. Ifthese aren’t part of our fictional landscape now, then they need to be. Otherwise one day we may find we have justfive years left. And it won’t just be the news readers weeping.

Check out my website: www.johnironmonger.com

October 25, 2023

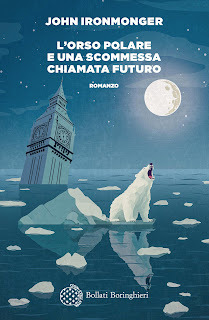

A brilliant but rather scary Italian cover for 'The Wager and the Bear.'

I thought I'd share this rather terrifying cover. A brilliant piece of art. Thanks to the great team at Bollati Boringheiri

I thought I'd share this rather terrifying cover. A brilliant piece of art. Thanks to the great team at Bollati Boringheiri

Check out my website www.johnironmonger.com

April 27, 2023

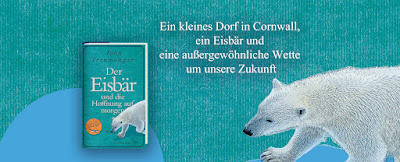

The Wager and the Bear (Der Eisbär und die Hoffnung auf morgen). [Posted: 27 April 2023]

The original idea for the story camefrom my brilliant agent, Stan. I told him I wanted to write a climate-changenovel, and he sent me an email in February 2021, describing a scenario he describedas a cross between Not Forgetting the Whale and Local Hero. Hecalled it ‘Not Forgetting the Iceberg.’ I rarely (normally) pick up on story-suggestionspeople give me but this was a rather compelling idea, and I found myselfsitting down and writing an experimental first chapter. Then of course I had towrite a second, and a third … and this is how novels get written. Stan wantedthe story to be set in Scotland. I wanted it back in Cornwall – in my fictionalvillage of St Piran. Stan saw the iceberg as the central threat. I saw theiceberg as a harbinger of a greater threat. And so I set about ignoring all Stan’sadvice, and now not much remains of his original story, alas, except for theiceberg. But the iceberg (as you will see if ever you read the novel) does playa very central part. It is a story still very rooted in St Piran, and both thehero, Tom, and the anti-hero, Monty, are St Piran boys. It is an action story,a love story, a story with real, terrifying jeopardy … and a story with a bear.

The challenge with any story aboutclimate change is to accommodate the long timescales. The climate catastropheis something that might be almost instantaneous in geological terms, but measuredagainst human lifespans it is ponderously snail-like. (See my last blog post https://notablebrain.blogspot.com/2023/04/climate-change-cats-and-spaghetti-essay.html)So unlike ‘Not Forgetting the Whale’ (Der Wal und das Ende der Welt) this storyunravels over a whole human lifetime. And during this lifetime we will come todiscover if Tom really is the hero and Monty the anti-hero. Or is it morenuanced?

Ido hope, if you can read German, you will discover this book. If you do, pleasewrite to let me know your reactions. You can message me through this blog. If,like me, you are limited to reading in English you might have to wait a littlelonger. I suspect UK publishers want to wait to see how well it does in Europe –and this is because my last novel, ‘The Many Lives of Heloise Starchild’ didn’tsell all that well in Britain. My counter to this is to explain that ‘Heloise’hit the bookshops in hardback when shops were closed due to Covid, and thepaperback launched when bookshops were closed again. It launched with virtuallyno publicity. There was, I suppose, very little point publicising a book whenthe shops were all shut. So it goes. It had a beautiful cover – but (in mymind) the title was wrong. My original title was, ‘Katya’s Gift,’ and I can’tshake off the feeling that it would have done better with that title. Heloiseis still my favourite novel by the way. And it is still out there if ever you’re lookingfor something new to read.

Anyway – all that aside, I can’t wait to see ‘TheWager and the Bear’ in print. Here again is that beautiful cover. And thank youonce again to the wonderful people at S.Fischer Verlag for having faith in me.

The Wager and the Bear (Der Eisbär und die Hoffnung auf morgen).

The original idea for the story camefrom my brilliant agent, Stan. I told him I wanted to write a climate-changenovel, and he sent me an email in February 2021, describing a scenario he describedas a cross between Not Forgetting the Whale and Local Hero. Hecalled it ‘Not Forgetting the Iceberg.’ I rarely (normally) pick up on story-suggestionspeople give me but this was a rather compelling idea, and I found myselfsitting down and writing an experimental first chapter. Then of course I had towrite a second, and a third … and this is how novels get written. Stan wantedthe story to be set in Scotland. I wanted it back in Cornwall – in my fictionalvillage of St Piran. Stan saw the iceberg as the central threat. I saw theiceberg as a harbinger of a greater threat. And so I set about ignoring all Stan’sadvice, and now not much remains of his original story, alas, except for theiceberg. But the iceberg (as you will see if ever you read the novel) does playa very central part. It is a story still very rooted in St Piran, and both thehero, Tom, and the anti-hero, Monty, are St Piran boys. It is an action story,a love story, a story with real, terrifying jeopardy … and a story with a bear.

The challenge with any story aboutclimate change is to accommodate the long timescales. The climate catastropheis something that might be almost instantaneous in geological terms, but measuredagainst human lifespans it is ponderously snail-like. (See my last blog post https://notablebrain.blogspot.com/2023/04/climate-change-cats-and-spaghetti-essay.html)So unlike ‘Not Forgetting the Whale’ (Der Wal und das Ende der Welt) this storyunravels over a whole human lifetime. And during this lifetime we will come todiscover if Tom really is the hero and Monty the anti-hero. Or is it morenuanced?

Ido hope, if you can read German, you will discover this book. If you do, pleasewrite to let me know your reactions. You can message me through this blog. If,like me, you are limited to reading in English you might have to wait a littlelonger. I suspect UK publishers want to wait to see how well it does in Europe –and this is because my last novel, ‘The Many Lives of Heloise Starchild’ didn’tsell all that well in Britain. My counter to this is to explain that ‘Heloise’hit the bookshops in hardback when shops were closed due to Covid, and thepaperback launched when bookshops were closed again. It launched with virtuallyno publicity. There was, I suppose, very little point publicising a book whenthe shops were all shut. So it goes. It had a beautiful cover – but (in mymind) the title was wrong. My original title was, ‘Katya’s Gift,’ and I can’tshake off the feeling that it would have done better with that title. Heloiseis still my favourite novel by the way. And it is still out there if ever you’re lookingfor something new to read.

Anyway – all that aside, I can’t wait to see ‘TheWager and the Bear’ in print. Here again is that beautiful cover. And thank youonce again to the wonderful people at S.Fischer Verlag for having faith in me.

April 13, 2023

Cats, and Spaghetti, and Climate Change [13 April 2023]

I can’t remember when (or where) I first heard the expression,‘herding cats.’ I don’t think this idiom was around when I was young. Sofar as I can tell, it was invented sometime in the 1980s and it took off. Sooneveryone was using it. It’s a great little saying because we all know enoughabout cats to understand right away what it means. ‘I did my best, but itwas like herding cats.’ At once we appreciate the futility, the complexity,and the sheer absence of co-operation from everyone concerned. You don’t getherds of cats. They are too bloody-minded.

My father had a saying that meant almost the same thing. Butnot quite. He would say, ‘it was like trying to organise spaghetti.’Somehow, for me, organising spaghetti feels like an enterprise even more doomedto failure than herding cats. The cats may not want to be herded, but there isat least the possibility that they might eventually succumb. Spaghetti on the otherhand will never submit to organisation. And unlike the cats this isn’t due to wilfulnessor contrariness. Disorganisation is a property of the spaghetti itself.

Efforts to resolve the climate-change crisis are oftencompared to herding cats. In this metaphor the ‘cats’ are the 195 countries on theplanet, across 7 continents, where no two countries think alike, or act alike,or have the same priorities, or enjoy similar political systems, or possess thesame resources, or have the same levels of understanding. How do we ever herdthese slippery belligerent cats into the same box? Even so, I worry that the problem is more likeorganising spaghetti. There is no way to do this. We’ll never get everyone onboard. Perhaps we ought to accept this and find a different way.

There is, by the way, a rather clever online tool called ‘GoogleNGram Viewer.’ It can help you to figure out when (but not necessarily where) aword or an expression arose. It searches millions of books over the past twocenturies, and if the words you’ve entered appear in 40 books or more in any calendaryear, it counts them and plots a graph to show how the frequency has changedwith time. Forty books feels like quitea high bar to me. If you enter ‘herding cats’ you won’t find any use ofthis expression until 1938. In 1942 the phrase disappears, and it doesn’treappear until 1987. After that the frequency graph rises meteorically, likethe lift-off of a space rocket. It is as if there was something that happenedin the Eighties that made this expression useful.

If, by the way, you try ‘organised spaghetti’ in NGramViewer you don’t get any results at all. Maybe this expression was exclusivelymy dad’s.

If I look up from my keyboard, and glance out of my window,I can see a storm coming. The clouds gathering over the estuary look as grey andheavy as gunmetal.

And now, in the time it has taken me to type that lastsentence, the storm is upon us. The rain is driving against my window. I nolonger have a view. Funny how the weathercan do that, and we all accept it. We look at the forecasts and we plan ourdays around them. Let’s do the beach on Sunday when the rain stops. Butif we’re told the whole global climate is changing, we go into a complex formof denial. We don’t really know how to plan.We hope that tomorrow will be much the same as today, and on the whole it is,and that gives us comfort. It makes us think this is nothing to worry about. Yet.

One metaphor I have heard used about climate change is ‘aslow-motion car crash.’ I used this myself in a novel, ‘The Wager andthe Bear.’ The image I wanted was ofan impending catastrophe where the parts are all in motion, where no one is yethurt, but where terrible death and destruction await if no one acts to stop it.A slow-motion car crash seems to tick all of those boxes. But all thesame, I’m not altogether happy with this metaphor. For a start it seems tooprosaic. (I’m using the word prosaic to mean lacking in poetry – but alsoto mean lacking in purpose.) I’ve tried to think of a better image. A traincrash is better perhaps, because it involves more people. But slow-motion isinsufficient to describe the slow and gradual increments of change that theclimate crisis delivers. Sea levels are rising by around four and a halfmillimetres a year. In ten years, at this rate, they will rise four and a halfcentimetres. And the sea, as we know, moves up and down, sometimes quiteerratically so that doesn’t feel like a threat. Not really. In a century thesea might rise forty five centimetres. About knee high. And none of us likes tothink forward more than a century. Do we?

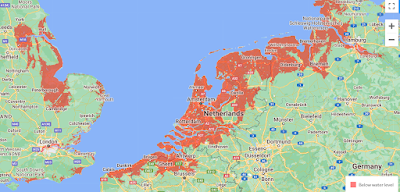

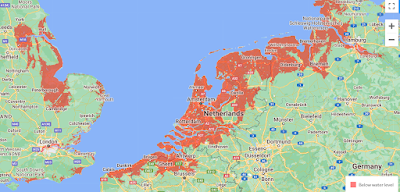

Isn’t that odd? We don’t have this blind spot with history.We’re fascinated by the lives of the Tudors (Henry VIII was on the throne 500years ago). We love stories about the Romans (2,000 years ago). And yet we don’tspeculate much on where our descendants might be in 500 or 2,000 years – what kindof world they will inhabit. Or what (since we chose this measurement) the sealevels might be. So let’s speculate then. Assume that sea levels keep on risingat 4.5mm a year (in reality the rate will almost certainly accelerate but let’signore that for a moment.) Our descendants in 2000 years will inherit seas 9metres higher than today. The map of the world will have been alteredirreversibly. Britain will have lost most of East and Central London, and greatswathes of the Thames Valley including towns like Dartford, and Kingston.Hundreds of seaside towns will have been wholly lost to the rising waters -places like Portsmouth, Southampton, Middlesborough and Blackpool, Cardiff andNewport, and Gloucester. Lincoln (now 38 miles from the sea) will be a seasidetown. So will whatever remains of Cambridge. So will York. So willTaunton. Across The Channel most of theNetherlands and much of Belgium will be underwater. So will huge tracts of Northern Germany.America will lose thousands of communities down the Eastern seaboard. China will lose Shanghai and Guangzhou. Bangkok and Kolkata and Ho Chi Minh City will be gone. And Basra, Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

And here’s the thing. The water will still be rising. Itstill has a way to go. If all the ice melts (and it probably will if globaltemperature rises by 4 degrees) then sea levels rise seventy metres or so.

9 metres of sea level rise puts the Netherlands underwater

9 metres of sea level rise puts the Netherlands underwaterAnd sea level changes are, perhaps, the least of ourworries. A 4 degree rise would make most of the world between the tropics practicallyuninhabitable. It would certainly make agriculture almost impossible. It will causecatastrophic drought . And the Northern farmlands which will now be warmer willnot take up the slack. Celestial mechanics will still restrict sunlight inwinter, and the soils are anyway very unproductive. And anyway a weird sideeffect of climate change might mean that as the world gets hotter (and sealevels keep rising) Europe curiously will get colder as ocean currents slowdown.

Finally there is a terrifying threat. This is how it might be in, 'The Year of the Dugong.' If atmospheric CO2levels exceed 1,200 parts per million (ppm) (and they could) it could push the Earth’s climateover a tipping point. This would see clouds start to break up, and, a cloudlessworld will reflect away less sunlight. According to research published in thejournal Nature Geoscience, this could trigger another 8°C rise in globalaverage temperatures. Game Over.

So slow-motion train crash doesn’t work, does it? ‘Ultra-slowmotion asteroid-collision,’ might be better. A disaster movie that runs atone frame a year. But the disaster is still going to happen. And it is inevitableunless we can herd the unruly cats who govern us and get them to startorganising the spaghetti. Now.

Cats, and Spaghetti, and Climate Change

I can’t remember when (or where) I first heard the expression,‘herding cats.’ I don’t think this idiom was around when I was young. Sofar as I can tell, it was invented sometime in the 1980s and it took off. Sooneveryone was using it. It’s a great little saying because we all know enoughabout cats to understand right away what it means. ‘I did my best, but itwas like herding cats.’ At once we appreciate the futility, the complexity,and the sheer absence of co-operation from everyone concerned. You don’t getherds of cats. They are too bloody-minded.

My father had a saying that meant almost the same thing. Butnot quite. He would say, ‘it was like trying to organise spaghetti.’Somehow, for me, organising spaghetti feels like an enterprise even more doomedto failure than herding cats. The cats may not want to be herded, but there isat least the possibility that they might eventually succumb. Spaghetti on the otherhand will never submit to organisation. And unlike the cats this isn’t due to wilfulnessor contrariness. Disorganisation is a property of the spaghetti itself.

Efforts to resolve the climate-change crisis are oftencompared to herding cats. In this metaphor the ‘cats’ are the 195 countries on theplanet, across 7 continents, where no two countries think alike, or act alike,or have the same priorities, or enjoy similar political systems, or possess thesame resources, or have the same levels of understanding. How do we ever herdthese slippery belligerent cats into the same box? Even so, I worry that the problem is more likeorganising spaghetti. There is no way to do this. We’ll never get everyone onboard. Perhaps we ought to accept this and find a different way.

There is, by the way, a rather clever online tool called ‘GoogleNGram Viewer.’ It can help you to figure out when (but not necessarily where) aword or an expression arose. It searches millions of books over the past twocenturies, and if the words you’ve entered appear in 40 books or more in any calendaryear, it counts them and plots a graph to show how the frequency has changedwith time. Forty books feels like quitea high bar to me. If you enter ‘herding cats’ you won’t find any use ofthis expression until 1938. In 1942 the phrase disappears, and it doesn’treappear until 1987. After that the frequency graph rises meteorically, likethe lift-off of a space rocket. It is as if there was something that happenedin the Eighties that made this expression useful.

If, by the way, you try ‘organised spaghetti’ in NGramViewer you don’t get any results at all. Maybe this expression was exclusivelymy dad’s.

If I look up from my keyboard, and glance out of my window,I can see a storm coming. The clouds gathering over the estuary look as grey andheavy as gunmetal.

And now, in the time it has taken me to type that lastsentence, the storm is upon us. The rain is driving against my window. I nolonger have a view. Funny how the weathercan do that, and we all accept it. We look at the forecasts and we plan ourdays around them. Let’s do the beach on Sunday when the rain stops. Butif we’re told the whole global climate is changing, we go into a complex formof denial. We don’t really know how to plan.We hope that tomorrow will be much the same as today, and on the whole it is,and that gives us comfort. It makes us think this is nothing to worry about. Yet.

One metaphor I have heard used about climate change is ‘aslow-motion car crash.’ I used this myself in a novel, ‘The Wager andthe Bear.’ The image I wanted was ofan impending catastrophe where the parts are all in motion, where no one is yethurt, but where terrible death and destruction await if no one acts to stop it.A slow-motion car crash seems to tick all of those boxes. But all thesame, I’m not altogether happy with this metaphor. For a start it seems tooprosaic. (I’m using the word prosaic to mean lacking in poetry – but alsoto mean lacking in purpose.) I’ve tried to think of a better image. A traincrash is better perhaps, because it involves more people. But slow-motion isinsufficient to describe the slow and gradual increments of change that theclimate crisis delivers. Sea levels are rising by around four and a halfmillimetres a year. In ten years, at this rate, they will rise four and a halfcentimetres. And the sea, as we know, moves up and down, sometimes quiteerratically so that doesn’t feel like a threat. Not really. In a century thesea might rise forty five centimetres. About knee high. And none of us likes tothink forward more than a century. Do we?

Isn’t that odd? We don’t have this blind spot with history.We’re fascinated by the lives of the Tudors (Henry VIII was on the throne 500years ago). We love stories about the Romans (2,000 years ago). And yet we don’tspeculate much on where our descendants might be in 500 or 2,000 years – what kindof world they will inhabit. Or what (since we chose this measurement) the sealevels might be. So let’s speculate then. Assume that sea levels keep on risingat 4.5mm a year (in reality the rate will almost certainly accelerate but let’signore that for a moment.) Our descendants in 2000 years will inherit seas 9metres higher than today. The map of the world will have been alteredirreversibly. Britain will have lost most of East and Central London, and greatswathes of the Thames Valley including towns like Dartford, and Kingston.Hundreds of seaside towns will have been wholly lost to the rising waters -places like Portsmouth, Southampton, Middlesborough and Blackpool, Cardiff andNewport, and Gloucester. Lincoln (now 38 miles from the sea) will be a seasidetown. So will whatever remains of Cambridge. So will York. So willTaunton. Across The Channel most of theNetherlands and much of Belgium will be underwater. So will huge tracts of Northern Germany.America will lose thousands of communities down the Eastern seaboard. China will lose Shanghai and Guangzhou. Bangkok and Kolkata and Ho Chi Minh City will be gone. And Basra, Abu Dhabi and Dubai.

And here’s the thing. The water will still be rising. Itstill has a way to go. If all the ice melts (and it probably will if globaltemperature rises by 4 degrees) then sea levels rise seventy metres or so.

9 metres of sea level rise puts the Netherlands underwater

9 metres of sea level rise puts the Netherlands underwaterAnd sea level changes are, perhaps, the least of ourworries. A 4 degree rise would make most of the world between the tropics practicallyuninhabitable. It would certainly make agriculture almost impossible. It will causecatastrophic drought . And the Northern farmlands which will now be warmer willnot take up the slack. Celestial mechanics will still restrict sunlight inwinter, and the soils are anyway very unproductive. And anyway a weird sideeffect of climate change might mean that as the world gets hotter (and sealevels keep rising) Europe curiously will get colder as ocean currents slowdown.

Finally there is a terrifying threat. This is how it might be in, 'The Year of the Dugong.' If atmospheric CO2levels exceed 1,200 parts per million (ppm) (and they could) it could push the Earth’s climateover a tipping point. This would see clouds start to break up, and, a cloudlessworld will reflect away less sunlight. According to research published in thejournal Nature Geoscience, this could trigger another 8°C rise in globalaverage temperatures. Game Over.

So slow-motion train crash doesn’t work, does it? ‘Ultra-slowmotion asteroid-collision,’ might be better. A disaster movie that runs atone frame a year. But the disaster is still going to happen. And it is inevitableunless we can herd the unruly cats who govern us and get them to startorganising the spaghetti. Now.