John Ironmonger's Blog, page 12

February 19, 2021

My Map Pins (3) Tsavo East National Park, Kenya

I was sixteen when I first went to Tsavo East. I went as a hanger-on/assistant to a zoologist from the University of Nairobi, and what we were supposed to be doing there was helping to measure the elephant population. How is that for a holiday job? From my memory, I can tell you there were an estimated 30,000 elephants in Tsavo at the time, but someone had apparently decided that a more accurate count was needed. The plan was for light aircraft to ‘bomb’ groups of elephant with white-wash and then for spotters in Landrovers (us) to criss-cross the park trying to spot and count those elephants with white spots. We stayed at the Tsavo Research Station and we spent every day in the park counting elephants. Tsavo East is larger than Yorkshire. We covered a lot of miles and counted a lot of elephants. One night we were invited to dinner with the park director – an ancient colonial character who shared stories of exploring Kenya on foot as a young man, and who told us of his encounters with the Ghost and the Darkness, the man-eating lions of Tsavo. Dinner concluded with a huge stilton cheese hollowed out and filled with port. Could you get more colonial than that? This was when I decided I wanted to be a zoologist.

I've been back to Tsavo with Sue. These pictures are from our visit in 2008. #tsavo What3Words: bookmaking.noted.fumbles

My Map Pins (1) Nairobi, Kenya

I've been doing that thing on Google Maps where you create a map of your life; you drop a pin into all the places you've been, and before long you have a world map dotted with your memories. No use to anyone of course, except as a rather fun exercise; but I had this idea to turn a few of my pins into blog posts. After all, I have been a rubbish blogger, and it is time I posted some more. So here we are, and I'm starting with Nairobi. This is where I was born - at the Princess Elizabeth Hospital (now the Kenyatta National Hospital). My dad was a civil servant, and we moved around a lot, but the house I remember most was the one Dad built - the home I grew up in. The address used to be Westfield Close, Lavington which is a terribly British address. Today it is Naushad Merali Drive. (See the What3Words link below). I used to know every inch of this neighbourhood. I explored it on my bike, and on foot with my best friend Bruce Bulley. In those days it was on the very edge of town, and you could set off on the Kikuyu paths into wild Kenya - watching out for snakes - and we regularly did. In my novel, 'The Notable Brain of Maximilian Ponder', this is where the early chapters are set. Adam Last, the voice of the book, lives conveniently in the very house where I did, and he explores the same paths.

I still miss Nairobi. To me it still feels like home. I still hope, one day, to go back.

WHAT3WORDS: returns.paddock.shame #thenotablebrainofmaximilianponder #nairobi

December 30, 2020

Why I shall always be a Remainer ...

That’s it. We’ve left the EU. We’ve swapped membership of a great international club for a sort of handwritten visitor’s-pass. We’ve done it to appease a motley and dubious crowd of braying nationalists. I don’t know, by the way, if this will make us richer, or if it will make us poorer. Neither do you. Neither does anyone. Both sides wheel-out their tame economic think-tanks to make contradictory forecasts. Yet even when Brexit has become old news, let’s say in ten years’ time, when all the dust has settled and economists have done their sums, do you know what? We still won’t know. We’ll still be arguing. Because who knows what the alternative future might have been? Remainers will say it would have been rosier. Leavers will say it would have been bleaker. Jacob Rees-Mogg will be telling us it will take fifty more years before we know. Well, good luck with that.

Here’s where I stand on the whole sorry argument. I’m a Remainer. I shall still be a Remainer even if Britain’s economy booms spectacularly after Brexit as Boris Johnson promises us it will, or equally, if it fails, as many economists and the Financial Times choose to believe. My argument, you see, has nothing to do with the economy, or trade deals, or customs unions, or tariffs. I’m not worried about the colour of our passports, or the plight of farmers in Northern Ireland, or lorries parking up on the M2 at Dover. Or fish. I am concerned however, about our belligerent desire to build barriers between peoples, as if somehow we are different, as if we breathe different air or have different numbers of legs. We are all related, the Brits, and the Belgians, and the Bulgars, and the Bolivians and every other label we can choose to hang around the necks of people, but we have lost sight of this. Let me demonstrate this. Consider your cousins. If your first cousin is someone who shares one (or usually two) of your grandparents, and your second cousin shares one of your great grandparents, it turns out that almost no one on the planet is more distant from you than a 27th cousin. Most people are a whole lot closer. We are all related. We have been fooled by ephemeral things like skin colour or language to imagine that humans belong in races or nationalities, but genetically we’re all pretty much the same. There is more genetic difference between a chimpanzee in Senegal and another in Uganda than there is between an Inuit and a Maori, or a Yorkshireman and a Chinaman. It really doesn’t help us to define ourselves by the patch of land where we happen to have been born (or the island we happen to think of as home). We are one human family, and if the world belongs to anyone, it belongs to all of us equally. Understanding this, and treating the world as our common responsibility, is the best (and possibly only) hope for our species. We only have one planet. It is the cradle and home of our species. Whether you were born in Ruislip or Rio, whether you’re a Briton or a Breton, a Ghanian or a Guyanian, we all have a right to live and breathe the same air, to grow up, to raise families, and to pursue happiness or whatever it is we want to pursue (within reason of course). And it seems to me that the biggest barrier we have to this great ideal is our almost religious devotion to the idea of the nation state with its precious little borders and its pretentions of autonomy. I like to think that one day, probably long after you and I are dust, the squabble of little nations and precious egos and tiny minded bigotries that infect our planet and keep us all at arm’s length will dissolve and we will come together as a people to manage, and curate this precious planet, and its tribes, and its wildlife, in a way we simply don’t do today. And in that regard I saw the European Union as one small, tentative, local, step in the right direction.

OK. So perhaps I’m a fantasist. But bear with me a little longer. The EU wasn’t (and isn’t) a perfect organisation. We agree on that. But it can (and does) legislate on environmental issues across a whole continent. That’s important. The EU has some of the world’s highest environmental standards, and laws passed in Brussels help protect natural habitats, keep air and water clean, ensure proper waste disposal, and help businesses move toward sustainable economies. Tin-pot nations that don’t belong to a global bloc like the EU don’t bother making these kinds of rules. Why should they? Only a big club like the EU can do this.

And the EU is growing. Or it was growing until Britain decided to take its ball away. It was nine countries. Now it’s 28. One day it might absorb countries in the Middle East, in Central Asia, and North Africa and who knows, it could, one day become a global union. I hope it does. I hope Brexit doesn’t put the brakes on this. And I hope, when it does finally reach a critical mass, it won’t be too late to save our planet from greedy, feuding, nation states.

Nation states are the problem. They’re not the solution. Not even Britain. Nation states like to think they can do whatever they want. They can make their own rules. And they do. But a world of competing nation states is a world that rapes the planet of its resources, that stifles the freedom of its people to travel, that overlooks famines and disasters in other countries. Nations go to war with other nations. Nations can’t manage the oceans. They can’t manage the climate. They can’t halt deforestation. They can’t stop mass extinctions.

Yet the idea of the nation state is so deeply embedded in our collective view of the world that it is a difficult shibboleth to topple. All around the world children learn about the glorious histories of their own nations. Every other country is a potential enemy. That’s the lesson we all grow up believing. Brexit was driven by a whole basket of grievances, but more than this, it was driven by a nationalistic belief in British exceptionalism, the idea that we are somehow better than the Poles and Hungarians, that the sun that shines on Britain is our sun, that the fish in the sea are ours, that Queen still rules an empire, and the map is still pink. But none of this is true.

The EU isn’t a global talking-shop like the UN. It’s a pragmatic single market with free trade and free movement and regulations and regulatory oversight and a court. It is an organisation that survives by respecting its members, celebrating their differences, and trying to find consensus. Imagine a world run like that. Is it such a bad idea? Really?

This is why I want to stay part of the club. I don’t expect Britain to rejoin for a generation at least – but I will support any campaign to rejoin. I’m a remainer. I will always be a remainer. And I’m proud of that.

Why I shall always be a Remainer That’s it. We’ve left t...

Why I shall always be a Remainer

That’s it. We’ve left the EU. We’ve swapped membership of a great international club for a sort of handwritten visitor’s-pass. We’ve done it to appease a motley and dubious crowd of braying nationalists. I don’t know, by the way, if this will make us richer, or if it will make us poorer. Neither do you. Neither does anyone. Both sides wheel-out their tame economic think-tanks to make contradictory forecasts. Yet even when Brexit has become old news, let’s say in ten years’ time, when all the dust has settled and economists have done their sums, do you know what? We still won’t know. We’ll still be arguing. Because who knows what the alternative future might have been? Remainers will say it would have been rosier. Leavers will say it would have been bleaker. Jacob Rees-Mogg will be telling us it will take fifty more years before we know. Well, good luck with that.

Here’s where I stand on the whole sorry argument. I’m a Remainer. I shall still be a Remainer even if Britain’s economy booms spectacularly after Brexit as Boris Johnson promises us it will, or equally, if it fails, as many economists and the Financial Times choose to believe. My argument, you see, has nothing to do with the economy, or trade deals, or customs unions, or tariffs. I’m not worried about the colour of our passports, or the plight of farmers in Northern Ireland, or lorries parking up on the M2 at Dover. Or fish. I am concerned however, about our belligerent desire to build barriers between peoples, as if somehow we are different, as if we breathe different air or have different numbers of legs. We are all related, us, and the Germans, and the Greeks, and the Georgians and every other label we can choose to hang around the necks of people, but we have lost sight of this. Let me demonstrate this. Consider your cousins. If your first cousin is someone who shares one (or usually two) of your grandparents, and your second cousin shares one of your great grandparents, it turns out that almost no one on the planet is more distant from you than a 20th cousin. Most people are a whole lot closer. We are all related. We have been fooled by ephemeral things like skin colour or language to imagine that humans belong in races or nationalities, but genetically we’re all pretty much the same. There is more genetic difference between a chimpanzee in Senegal and another in Uganda than there is between an Inuit and a Maori, or a Yorkshireman and a Chinaman. It really doesn’t help us to define ourselves by the patch of land where we happen to have been born (or the island we happen to think of as home). We are one human family, and if the world belongs to anyone, it belongs to all of us equally. Understanding this, and treating the world as our common responsibility, is the best (and possibly only) hope for our species. We only have one planet. It is the cradle and home of our species. Whether you were born in Ruislip or Rio, whether you’re a Briton or a Breton, a Ghanian or a Guyanian, we all have a right to live and breathe the same air, to grow up, to raise families, and to pursue happiness or whatever it is we want to pursue (within reason of course). And it seems to me that the biggest barrier we have to this great ideal is our almost religious devotion to the idea of the nation state with its precious little borders and its pretentions of autonomy. I like to think that one day, probably long after you and I are dust, the squabble of little nations and precious egos and tiny minded bigotries that infect our planet and keep us all at arm’s length will dissolve and we will come together as a people to manage, and curate this precious planet, and its tribes, and its wildlife, in a way we simply don’t do today. And in that regard I saw the European Union as one small, tentative, local, step in the right direction.

OK. So perhaps I’m a fantasist. But bear with me a little longer. The EU wasn’t (and isn’t) a perfect organisation. We agree on that. But it can (and does) legislate on environmental issues across a whole continent. That’s important. The EU has some of the world’s highest environmental standards, and laws passed in Brussels help protect natural habitats, keep air and water clean, ensure proper waste disposal, and help businesses move toward sustainable economies. Tin-pot nations that don’t belong to a global bloc like the EU don’t bother making these kinds of rules. Why should they? Only a big club like the EU can do this.

And the EU is growing. Or it was growing until Britain decided to take its ball away. It was nine countries. Now it’s 28. One day it might absorb countries in the Middle East, in Central Asia, and North Africa and who knows, it could, one day become a global union. I hope it does. I hope Brexit doesn’t put the brakes on this. And I hope, when it does finally reach a critical mass, it won’t be too late to save our planet from greedy, feuding, nation states.

Nation states are the problem. They’re not the solution. Not even Britain. Nation states like to think they can do whatever they want. They can make their own rules. And they do. But a world of competing nation states is a world that rapes the planet of its resources, that stifles the freedom of its people to travel, that overlooks famines and disasters in other countries. Nations go to war with other nations. Nations can’t manage the oceans. They can’t manage the climate. They can’t halt deforestation. They can’t stop mass extinctions.

Yet the idea of the nation state is so deeply embedded in our collective view of the world that it is a difficult shibboleth to topple. All around the world children learn about the glorious histories of their own nations. Every other country is a potential enemy. That’s the lesson we all grow up believing. Brexit was driven by a whole basket of grievances, but more than this, it was driven by a nationalistic belief in British exceptionalism, the idea that we are somehow better than the Poles and Hungarians, that the sun that shines on Britain is our sun, that the fish in the sea are ours, that Queen still rules an empire, and the map is still pink. But none of this is true.

The EU isn’t a global talking-shop like the UN. It’s a pragmatic single market with free trade and free movement and regulations and regulatory oversight and a court. It is an organisation that survives by respecting its members, celebrating their differences, and trying to find consensus. Imagine a world run like that. Is it such a bad idea? Really?

This is why I want to stay part of the club. I don’t expect Britain to rejoin for a generation at least – but I will support any campaign to rejoin. I’m a remainer. I will always be a remainer. And I’m proud of that.

April 14, 2020

How do we lift the COVID lock-down?

But now, because of Social Distancing, we are told the R-Zero has fallen to 0.65. This is a cause for some celebration. Well done us. But here comes the maths. So far in Britain, 88,000 people have tested positive. That’s probably a huge under-estimate, but let’s go with it. Let’s assume just 10,000 people are infectious today. These people will infect 6,500 people, who in turn will infect 4,225, and we will all get excited because we will see new cases dropping; but when will it be safe to go back to normal? At this rate, the maths tells us, after two months there will still be 319 infected people out in the community and given the way this whole thing kicked off with just one super-spreader it still won’t be safe to let us all out. On these figures it would take 22 weeks before we eliminate the virus. That takes us to mid-September. If the starting figure in our calculation is not 10,000 infectious people, but say, 1 million infectious people (not entirely unrealistic) then we would need to be in lockdown until December.

Nobody believes the economy could stand that. Or our frayed nerves.

So what we will probably see is a relaxing of lockdown with the aim of keeping R-Zero to less than one. (By the way an R-Zero of 0.9 with a starting point of 10,000 sick people would take us until November 2021 to eliminate the virus – 20 months instead of 6, so we do need to keep the figure as low as we can). Anyway, here are my humble suggestions for how we do it.

1) Re-open shops and businesses but enforce social distancing. This would mean the return of bookshops, shoe-shops, high streets, and retail parks. We could visit museums and galleries and zoos and gardens. They would operate Tesco-style rules for distancing, and they would need to provide hand sanitiser and employ cleaners to disinfect surfaces regularly – but we’re getting used to these things. Bars and restaurants might be trickier – but with fewer tables and table-service and beer gardens we could see some of these too. Construction work should restart.

2) Ask people to wear facemasks away from home.Of course facemasks aren’t perfect and of course we need to be taught how to use them safely – but they would surely help shave a few decimal points off the R-Zero by helping to stop infected people passing the virus onto others. The difference between R-Zero of 0.9 and R-Zero of 0.8 is nine months and a lot of lives saved. So it must be worth doing.

3) Open up parks and beaches and public places. Lift restrictions on travel for leisureIt’s nearly summer. We need places to walk, to run, to play frisbee, to paddle. We shouldn’t be closing these places down. We should be encouraging people to go to beaches so long as the social distancing rules can be observed. We should encourage farms to open up fields for ramblers. We should get people back onto golf courses and tennis courts. If you want to drive an hour to Snowdonia to walk – then why not? Sunbathe if you want to. We need to ask people to be sensible. If the car park is packed, maybe look for somewhere else to walk.

4) Allow larger groups to congregate.At the moment we cannot meet in groups larger than two. But if you and your friends or family have been diligently social distancing for four weeks then it is very low risk for you to meet up – say for a meal or a walk. The rules should say any group with mutual trust (ie everyone trusts that all others have been vigilant) can now meet socially.

5) Develop small-unit schools.If a school has 500 kids tearing around in the playground then it is a potential virus risk. So when kids go back to school we need to keep them, so far as we can, in class groups where they only mix with a limited number of others. Schools should look at spreading classes around in church halls, community centres and other closed venues to reduce the risks.

6) Track us allHang the social liberties concerns – let’s all agree to carry tracking apps until this pandemic is defeated. Then if anyone anywhere tests positive for Covid – a dozen phones will ping to let people know they might have been infected and they should get themselves into quarantine. Lets get the NHS app out there as soon as possible.

That’s it. Those are my thoughts. What about you?

February 12, 2020

Covid-19 / Corona Virus and Not Forgetting the Whale

First an apology. I’m a rubbish blogger. This is my first post since my sixtieth birthday blog, and that was, ahem, five and a bit years ago. My blog history has skipped right past my third novel, ‘Not Forgetting the Whale,’ as if it never happened, and I probably ought to be thinking about blogging ahead of my next book, ‘The Many Lives of Heloise Starchild.’ But events of recent weeks (I’m thinking now about the Covid-19 Corona Virus) have reminded me of Not Forgetting the Whale, so maybe it is time, at last, for a blog.

Not Forgetting the Whale (if you haven’t read it) is a whimsical and slightly allegorical tale about the collapse of civilisation following a worldwide flu pandemic. If that sounds a little heavy, it might help to add that the story is told almost entirely from the perspective of a tiny Cornish fishing community. The fictional village of St Piran was a familiar environment for me to write about. I was seventeen when my family left Nairobi and reinvented themselves as shopkeepers in Mevagissey, a village on the Cornish coast. My mother had grown up there, and she longed to go back. My parents bought a general store in the square, right by the harbour, and I worked there, during school and university holidays, stacking shelves, slicing bacon, and delivering groceries to houses around the village. One of my regular deliveries was to the writer Colin Wilson who lived a short way out of town in a rambling old farmhouse. It was a real writer’s home – filled with books. ‘I should love to be a writer,’ I told him once, after I had carried a box of groceries into his kitchen. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘if you want to be a writer, then you will be. You won’t have any choice.’

I thought, at first, I would hate Mevagissey. My friends were far away, and this little town (especially in winter) was desperately quiet and remote. But, like Joe, the protagonist of Whale, I discovered instead a most extraordinary community. Within weeks I had learned the names and faces of dozens of villagers, I had made new friends, and I had started to understand the support network that every villager seemed to be part of. It was unexpected. It was a joy.

I wanted to write about this for a long time. What I needed was a story. On a train from London to Liverpool I found myself reading a magazine article by the science writer Debora Mackenzie. The title of the article was, ‘Could a Pandemic bring down Western Civilisation?’ The idea was simple, yet terrifying. Complexity theory suggests that once a society develops beyond a certain level, it becomes dangerously fragile. It reaches a point where even a minor disturbance can bring everything crashing down. A pandemic flu – for example. I had my story. I became fascinated by arcane things like … supply chains. The whole way our civilisation works – even the systems involved in putting food onto our tables - has become labyrinthine in its complexity, involving high-tech farm machinery, refrigerated warehouses, networks of specialist distributors, and complicated packaging. It relies on the availability of fuel, spare parts for all the machines, the health and reliability of drivers and packers and dozens of other trades, the electronic exchange of currency, good road, rail, and other transport networks, and who knows how easy it would be for any one of these systems to fail. The fact that it all works amazingly well means we don’t tend to think of it as a risky process. And yet it is. A small disruption could grind the whole machine to a halt.

This is the central thesis behind Not Forgetting the Whale. A pandemic flu, originating in the Far East, is brought unwittingly to Britain by passengers on a long distance flight, and after that, public fear takes over. Oil imports stop. Key workers stay home. Power stations grind to a halt. Shops are raided and shelves are emptied of produce. I had a quotation in my mind, ‘Civilisation is only three square meals away from anarchy.’ This quotation (from the TV Series Red Dwarf) drove the story.

And now, here we are facing Covid-19. It’s a flu-like virus from China that threatens to explode into a pandemic. Could it lead to the same situation that faces St Piran in The Whale?

And I suppose the answer has to be … yes.

But there is a glimmer of hope. In Not Forgetting the Whale the forecast for humanity is grim. But humankind (in general) and St Piran (in particular) defy the pundits and bounce back. They do this by, well, … pulling together and sharing things, and generally being nice to one another. They overturn all the assumptions of apocalyptic fiction that see us hunkering down with shotguns and fighting over the last scrap of bread. The flu virus, far from destroying us, ends up bringing us closer together. Maybe that should give us hope.

Although the villagers of St Piran do have the help of a whale, of course. Let’s not forget that.

Corvid-19 / Corona Virus and Not Forgetting the Whale

First an apology. I’m a rubbish blogger. This is my first post since my sixtieth birthday blog, and that was, ahem, five and a bit years ago. My blog history has skipped right past my third novel, ‘Not Forgetting the Whale,’ as if it never happened, and I probably ought to be thinking about blogging ahead of my next book, ‘The Many Lives of Heloise Starchild.’ But events of recent weeks (I’m thinking now about the Corvid-19 Corona Virus) have reminded me of Not Forgetting the Whale, so maybe it is time, at last, for a blog.

Not Forgetting the Whale (if you haven’t read it) is a whimsical and slightly allegorical tale about the collapse of civilisation following a worldwide flu pandemic. If that sounds a little heavy, it might help to add that the story is told almost entirely from the perspective of a tiny Cornish fishing community. The fictional village of St Piran was a familiar environment for me to write about. I was seventeen when my family left Nairobi and reinvented themselves as shopkeepers in Mevagissey, a village on the Cornish coast. My mother had grown up there, and she longed to go back. My parents bought a general store in the square, right by the harbour, and I worked there, during school and university holidays, stacking shelves, slicing bacon, and delivering groceries to houses around the village. One of my regular deliveries was to the writer Colin Wilson who lived a short way out of town in a rambling old farmhouse. It was a real writer’s home – filled with books. ‘I should love to be a writer,’ I told him once, after I had carried a box of groceries into his kitchen. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘if you want to be a writer, then you will be. You won’t have any choice.’

I thought, at first, I would hate Mevagissey. My friends were far away, and this little town (especially in winter) was desperately quiet and remote. But, like Joe, the protagonist of Whale, I discovered instead a most extraordinary community. Within weeks I had learned the names and faces of dozens of villagers, I had made new friends, and I had started to understand the support network that every villager seemed to be part of. It was unexpected. It was a joy.

I wanted to write about this for a long time. What I needed was a story. On a train from London to Liverpool I found myself reading a magazine article by the science writer Debora Mackenzie. The title of the article was, ‘Could a Pandemic bring down Western Civilisation?’ The idea was simple, yet terrifying. Complexity theory suggests that once a society develops beyond a certain level, it becomes dangerously fragile. It reaches a point where even a minor disturbance can bring everything crashing down. A pandemic flu – for example. I had my story. I became fascinated by arcane things like … supply chains. The whole way our civilisation works – even the systems involved in putting food onto our tables - has become labyrinthine in its complexity, involving high-tech farm machinery, refrigerated warehouses, networks of specialist distributors, and complicated packaging. It relies on the availability of fuel, spare parts for all the machines, the health and reliability of drivers and packers and dozens of other trades, the electronic exchange of currency, good road, rail, and other transport networks, and who knows how easy it would be for any one of these systems to fail. The fact that it all works amazingly well means we don’t tend to think of it as a risky process. And yet it is. A small disruption could grind the whole machine to a halt.

This is the central thesis behind Not Forgetting the Whale. A pandemic flu, originating in the Far East, is brought unwittingly to Britain by passengers on a long distance flight, and after that, public fear takes over. Oil imports stop. Key workers stay home. Power stations grind to a halt. Shops are raided and shelves are emptied of produce. I had a quotation in my mind, ‘Civilisation is only three square meals away from anarchy.’ This quotation (from the TV Series Red Dwarf) drove the story.

And now, here we are facing Corvid-19. It’s a flu-like virus from China that threatens to explode into a pandemic. Could it lead to the same situation that faces St Piran in The Whale?

And I suppose the answer has to be … yes.

But there is a glimmer of hope. In Not Forgetting the Whale the forecast for humanity is grim. But humankind (in general) and St Piran (in particular) defy the pundits and bounce back. They do this by, well, … pulling together and sharing things, and generally being nice to one another. They overturn all the assumptions of apocalyptic fiction that see us hunkering down with shotguns and fighting over the last scrap of bread. The flu virus, far from destroying us, ends up bringing us closer together. Maybe that should give us hope.

Although the villagers of St Piran do have the help of a whale, of course. Let’s not forget that.

July 4, 2014

Glastonbarby ... and the significance of sixty

Deep breath.

Here goes ...

... in four days time I shall be sixty.

Ouch!

It might be easier if the birthday cards were kinder. Instead the convention seems to be a comical card with a sting inside. 'At your age it's a good idea to test your hearing,' reads one. 'So I bought you this musical card.' (Hint: It isn't a musical card.) 'You're at a wise age,' headlines another. And inside, 'wise my hair falling out? Wise my memory going?'

Oh well.

We had a fabulous party, (Glastonbarby) with sixty (natch) wonderful guests. We set up our mini-marquee and my brilliant son-in-law Ian fixed up a live link to the Glastonbury Festival on a colossal screen and we all ate hog roast, and drank Pimms and countless bottles of wine to the sounds of Metallica and Brian Ferry and we all partied ridiculously late into the night. Mike (Plymouth to Banjul) Taylor set off the biggest firework display I've seen for ages. Sue made an amazing cake. And our kids showed an embarrassing surprise video montage (Sixty Years in the Making) with photographs of me from childhood to bloated old age (including a picture of me in a frock as Mariana of the Moated Grange in a school production of Measure for Measure - not the sort of family photo I'd normally choose to share.) There were surprise guests. There were balloons. There was bunting with my face and age. There was an awful lot of hugging. Actually it was just about the best barbecue night I could imagine. Twenty one people stayed the night and the next morning we barbecued bacon and sausages and black pudding and Sue made a huge trough of scrambled eggs and the sun shone. Thank you to everyone who came, who helped with food and tents and loads of other stuff. It was awesome. You were awesome.

And here's the thing. I don't feel sixty. Really I don't. I've figured out that it isn't a milestone at all. It isn't this big deal. It's just a day, and hey, tomorrow will be another one. Two of our best friends bought me a T-shirt that reads 'Old Guy,' on the front. 'It fits perfectly,' I've told them. 'But I've put it in the drawer. I'm keeping it for when I get old.'

May 15, 2014

A New Cover Revealed

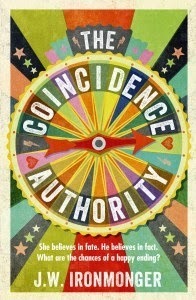

I don’t imagine Dickens lost an awful lot of sleep worrying about the cover designs for his novels. ‘Bleak House,’ he might have thought, ‘let’s go for a plain cover, in brown leather, with the title embossed in gold.’ ‘Ah Charles,’ the publisher might have said, ‘we’re toying with a plain red cover with a silver embossed title.’ Controversial. But these days - covers matter. They matter a lot. It can be irksome for a writer who has spent two years working on a novel to discover that the cover is the main topic of interest for the local book group. But publishers too, get very exercised by cover designs. Of course they do. A good cover can sell a lot of books. A poor cover can consign a book to the remainders store. Enter one of the most important people in the business - the cover designer. The cover designer has to be an artist, an alchemist, and a magician. He or she has to capture the essence of a novel in a single image, has to make it striking, compelling, and simultaneously unique. It has to be a cover you wouldn’t be embarrassed to be hiding behind on the tube, but a cover that will catch your eye on a book shelf. It has to scatter hints on genre and location and mood. It has to be serious. It has to be light. Who, I wonder, would be a cover designer? I love the hardback cover for ‘The Coincidence Authority.’ The plain image of the seagull and the sharp blue of the background seem to capture the whimsical essence of the story in a clear, eye-catching way. I also love the dreamy, faraway qualities of the US cover So I was a little surprised when Orion’s brilliant paperback editor Gail Paten told me that she was commissioning a redesign. Did it need one? ‘Yes,’ she told me. And she was pretty emphatic. Paperbacks are different creatures to hardbacks. The rules change. We talked about some of the ideas. Should it reflect the African themes of the story? Or something else?Today W&N have revealed the new cover, and Gail has blogged about the hard work that went into the design. You can read her blog here: http://www.wnblog.co.uk/2014/05/the-art-of-reinvention/It is humbling to discover just how many people and how many ideas and how much talent went into the new cover. But for me it is perfect. It captures, with the wheel of fortune, the essential mystery of chance that lies at the heart of the book, with echoes of the fairground where the young Azalea is abandoned, and hints of a buried romance; and it does all this in a brilliantly colourful way. The tag line if perfect (She believes in fate. He believes in fact. What are the chances of a happy ending?) It is so good, I wish I’d written it myself. So thank you Gail, and Steve and Edward and everyone else who contributed. I absolutely love the cover.

I don’t imagine Dickens lost an awful lot of sleep worrying about the cover designs for his novels. ‘Bleak House,’ he might have thought, ‘let’s go for a plain cover, in brown leather, with the title embossed in gold.’ ‘Ah Charles,’ the publisher might have said, ‘we’re toying with a plain red cover with a silver embossed title.’ Controversial. But these days - covers matter. They matter a lot. It can be irksome for a writer who has spent two years working on a novel to discover that the cover is the main topic of interest for the local book group. But publishers too, get very exercised by cover designs. Of course they do. A good cover can sell a lot of books. A poor cover can consign a book to the remainders store. Enter one of the most important people in the business - the cover designer. The cover designer has to be an artist, an alchemist, and a magician. He or she has to capture the essence of a novel in a single image, has to make it striking, compelling, and simultaneously unique. It has to be a cover you wouldn’t be embarrassed to be hiding behind on the tube, but a cover that will catch your eye on a book shelf. It has to scatter hints on genre and location and mood. It has to be serious. It has to be light. Who, I wonder, would be a cover designer? I love the hardback cover for ‘The Coincidence Authority.’ The plain image of the seagull and the sharp blue of the background seem to capture the whimsical essence of the story in a clear, eye-catching way. I also love the dreamy, faraway qualities of the US cover So I was a little surprised when Orion’s brilliant paperback editor Gail Paten told me that she was commissioning a redesign. Did it need one? ‘Yes,’ she told me. And she was pretty emphatic. Paperbacks are different creatures to hardbacks. The rules change. We talked about some of the ideas. Should it reflect the African themes of the story? Or something else?Today W&N have revealed the new cover, and Gail has blogged about the hard work that went into the design. You can read her blog here: http://www.wnblog.co.uk/2014/05/the-art-of-reinvention/It is humbling to discover just how many people and how many ideas and how much talent went into the new cover. But for me it is perfect. It captures, with the wheel of fortune, the essential mystery of chance that lies at the heart of the book, with echoes of the fairground where the young Azalea is abandoned, and hints of a buried romance; and it does all this in a brilliantly colourful way. The tag line if perfect (She believes in fate. He believes in fact. What are the chances of a happy ending?) It is so good, I wish I’d written it myself. So thank you Gail, and Steve and Edward and everyone else who contributed. I absolutely love the cover. What do you think? Please let me know …

February 13, 2014

Father of the Bride ...

I hadn’t expected to be quite so emotional. I know I’d written a teary speech, and I’d joked to one and all that I’d be welling up, but deep inside I thought I’d sail through with my usual jolly demeanour. And then, five minutes before collecting my beautiful daughter, Zoe, from her room, one of the bridesmaids brought me a gift. It was from Zoe. A watch. On the back was engraved, ‘Dad – Forever your little girl.’

I hadn’t expected to be quite so emotional. I know I’d written a teary speech, and I’d joked to one and all that I’d be welling up, but deep inside I thought I’d sail through with my usual jolly demeanour. And then, five minutes before collecting my beautiful daughter, Zoe, from her room, one of the bridesmaids brought me a gift. It was from Zoe. A watch. On the back was engraved, ‘Dad – Forever your little girl.’ And that was it. I was in bits.

I went to collect Zoe and when she emerged, like a butterfly from a chrysalis, she was so beautiful I was crying like a baby.

Giving a daughter away should be the hardest thing in the world, but it’s the easiest. I’ve never seen Zoe looking so lovely, or so happy. My hand was shaking when I walked her up the aisle. I’m so happy for her, and I’m happy for my wonderful new son-in-law Ian (whom we all love).

It was a spectacular wedding. We took over the Wordsworth Hotel in Grasmere right in the heart of the English Lakes. In practice we seemed to take over the whole village. This was February. No one else was there. Every time I crossed the square I bumped into wedding guests. It should have rained – but it didn’t. The sun shone. The Prosecco flowed. We had a brilliant cartoonist (Christopher Murphy), a stunning band (Superfreak), an amazing cake (Val Cooper), heart-stopping floral displays (Gill Maxim) and a whole load of wonderful guests. I only left the dance floor once in three hours. So thank you to my lovely wife Sue (who also looked gorgeous), to all our friends and relations, and to everyone who helped make the day go so well – the bridesmaids were fabulous – the best man was hilarious – the fireworks were awesome – the photographer was a genius - the flowers were spectacular; but thank you most of all to my stunningly beautiful daughter. I will never forget the day I gave you away. Forever your Dad.