Eric C. Sheninger's Blog, page 37

May 20, 2018

Digital Leadership is Not Optional

“Leadership has less to do with position than it does disposition.” – John Maxwell

I am currently working on a new edition of Digital Leadership for Corwin and I am very excited, as it will be in color. There are many changes I intend to make, but the most significant will be creating a book that is more “evergreen,” a book with less focus on tools and more on the dispositions of digital leaders. I would love your feedback after reading this post. What would you like to see emphasized in this new edition? What should be removed?

A great deal has changed since Digital Leadership was published in 2014. For starters, I have now been going on four years since transitioning from high school principal to Senior Fellow with the International Center for Leadership in Education (ICLE). Society is now in the midst of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which was in its infancy as I began writing this book. Personalized and blended learning pathways were proclaimed to be the future of education. More and more schools have gone 1:1 thanks to the cost-effectiveness of the Chromebook and cloud-based tools. Makerspaces have moved from fringe initiatives to vibrant components of school culture. Emerging technologies such as augmented reality, virtual reality, open education resources (OER), coding, and adaptive learning tools are moving more into the mainstream in some schools. Twitter chats have increased from a handful to now hundreds happening on a weekly basis.

What I have described above only accounts for a small subset of the changes we have seen since 2014. Change isn’t coming; it is already on our doorstep and about to knock down the front door. The need for digital leadership now is more urgent than a few years ago. Our learners will need to thrive and survive in a world that is almost impossible to predict thanks to exponential advances in technology. Automation and robotics are already disrupting the world of work, as we know it. The Internet of Things (IoT) impacts virtually all of us. Have you heard of it? Perhaps not, but once you know what it is you can see how it connects to your life. Wikipedia defines IoT as a network of physical devices, vehicles, home appliances and other items embedded with electronics, software, sensors, actuators, and connectivity which enables these objects to connect and exchange data. How are we preparing learners for this world? How are we adapting and evolving?

Image credit

Image credit

Expectations are also changing in a knowledge and information-based society where information can easily be accessed from virtually anywhere. The World Wide Web has transformed how we access, consume, create, and share information. From a growth perspective, the Personal Learning Network (PLN) concept has dramatically impacted countless educators across the globe. People craving more than a drive-by event, traditional school professional development day, or mandated training have an authentic outlet that caters to their interests. As educators lust for knowledge, parents and other stakeholders desire more information about schools and how the needs of learners are being met. Engagement using a multifaceted, two-way approach seems to be a no-brainer at a time when email has lost some luster. Providing pertinent information in a timely fashion helps to build powerful relationships and is a more substantial component of working smarter, not harder.

There is so much more than I can say, but to sum it all up digital leadership in our classrooms, schools, districts, and organizations is needed now more than ever. Research has shown how crucial digital leadership is to organizations. Here is a little bit that Josh Bersin shared in an article titled Digital Leadership is Not an Optional Part of Being a CEO:

Definitions of digital leadership vary and have pretty much become a semantic issue. Leadership is leadership ladies and gentlemen. The same general tenets that embody all great leaders we have come to respect and admire over time still apply. With this being said, I am slightly biased towards my definition created years ago that aligns well with Josh Bersin’s thinking.

Image credit

I now turn to all of you. Even though I think I know where I want to go with this edition the fact is that I am not writing a book for me – I am writing it for all of you! Please use the comment section below to share your insights and ideas on what should be included as well as de-emphasized. I am also looking to add great images that align to each of the seven pillars with credit. Thanks in advance!

I am currently working on a new edition of Digital Leadership for Corwin and I am very excited, as it will be in color. There are many changes I intend to make, but the most significant will be creating a book that is more “evergreen,” a book with less focus on tools and more on the dispositions of digital leaders. I would love your feedback after reading this post. What would you like to see emphasized in this new edition? What should be removed?

A great deal has changed since Digital Leadership was published in 2014. For starters, I have now been going on four years since transitioning from high school principal to Senior Fellow with the International Center for Leadership in Education (ICLE). Society is now in the midst of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, which was in its infancy as I began writing this book. Personalized and blended learning pathways were proclaimed to be the future of education. More and more schools have gone 1:1 thanks to the cost-effectiveness of the Chromebook and cloud-based tools. Makerspaces have moved from fringe initiatives to vibrant components of school culture. Emerging technologies such as augmented reality, virtual reality, open education resources (OER), coding, and adaptive learning tools are moving more into the mainstream in some schools. Twitter chats have increased from a handful to now hundreds happening on a weekly basis.

What I have described above only accounts for a small subset of the changes we have seen since 2014. Change isn’t coming; it is already on our doorstep and about to knock down the front door. The need for digital leadership now is more urgent than a few years ago. Our learners will need to thrive and survive in a world that is almost impossible to predict thanks to exponential advances in technology. Automation and robotics are already disrupting the world of work, as we know it. The Internet of Things (IoT) impacts virtually all of us. Have you heard of it? Perhaps not, but once you know what it is you can see how it connects to your life. Wikipedia defines IoT as a network of physical devices, vehicles, home appliances and other items embedded with electronics, software, sensors, actuators, and connectivity which enables these objects to connect and exchange data. How are we preparing learners for this world? How are we adapting and evolving?

Image credit

Image creditExpectations are also changing in a knowledge and information-based society where information can easily be accessed from virtually anywhere. The World Wide Web has transformed how we access, consume, create, and share information. From a growth perspective, the Personal Learning Network (PLN) concept has dramatically impacted countless educators across the globe. People craving more than a drive-by event, traditional school professional development day, or mandated training have an authentic outlet that caters to their interests. As educators lust for knowledge, parents and other stakeholders desire more information about schools and how the needs of learners are being met. Engagement using a multifaceted, two-way approach seems to be a no-brainer at a time when email has lost some luster. Providing pertinent information in a timely fashion helps to build powerful relationships and is a more substantial component of working smarter, not harder.

There is so much more than I can say, but to sum it all up digital leadership in our classrooms, schools, districts, and organizations is needed now more than ever. Research has shown how crucial digital leadership is to organizations. Here is a little bit that Josh Bersin shared in an article titled Digital Leadership is Not an Optional Part of Being a CEO:

Culture is key. Success is mostly dependent on people sharing information with each other, partnering, and continuously educating themselves. This can happen when you build a collective, transparent, and profoundly shared culture. CEOs who are digital leaders are continuously reinforcing the culture, communicating values, and aligning people around the culture whenever something goes wrong.The importance outlined above extends well beyond the private sector and into the field of education. As times change, so must the practice of leaders to establish a culture of learning that is relevant, research-based, and rooted in relationships. Digital leadership is all about people and how their collective actions aligned with new thinking, ideas, and tools can help to build cultures primed for success.

Definitions of digital leadership vary and have pretty much become a semantic issue. Leadership is leadership ladies and gentlemen. The same general tenets that embody all great leaders we have come to respect and admire over time still apply. With this being said, I am slightly biased towards my definition created years ago that aligns well with Josh Bersin’s thinking.

Digital leadership is a strategic mindset and set of behaviors that leverage resources to create a meaningful, transparent, and engaging school culture.The digital before leadership implies how mindsets and behaviours must change to harness current and emerging resources to set the stage for improving outcomes and professional practice. The Pillars of Digital Leadership provide a focus that can move us from talk to implementation and eventually evidence of improved outcomes. These guiding elements are embedded throughout all school cultures, which compel us in many cases to do what we already do better. I hope to flesh out each of these pillars more than I did the first time while also including many more strategies to aid in practical implementation. As for other significant inclusions, efficacy will be a substantial component of this edition as it was reasonably absent the first go around.

Image credit

I now turn to all of you. Even though I think I know where I want to go with this edition the fact is that I am not writing a book for me – I am writing it for all of you! Please use the comment section below to share your insights and ideas on what should be included as well as de-emphasized. I am also looking to add great images that align to each of the seven pillars with credit. Thanks in advance!

Published on May 20, 2018 05:39

May 13, 2018

Finding Comfort in Growth

"Comfort is the enemy of progress." - Hugh Jackman, The Greatest Showman

Have you ever been complacent when it comes to undertaking or performing a task? Of course, you have, as this is just a part of human nature. In our personal lives, complacency can result if we are happy or content with where we are. Maybe we don’t change our work out routines because we have gotten used to doing the same thing day in and day out. I know I love using the elliptical for cardio, but rarely use any setting beside manual. Or perhaps our diet doesn’t change as we have an affinity for the same types of foods, which might or might not be that good for us. So, what’s my point with all of this? It is hard to grow and improve if one is complacent. This is why we must always be open to finding comfort in growth. If we don’t, then things might very well never change.

The issue described above is not just prevalent in our personal lives. Complacency plagues many organizations as well. When we are in a state of relative comfort with our professional practice, it is often difficult to move beyond that zone of stability and dare I say, “easy” sailing. If it isn’t broke, then why fix it, right? Maybe we aren’t pushed to take on new projects or embrace innovative ideas. Or perhaps there is no external accountability to improve really. Herein lies the inherent challenge of taking on the status quo in districts, schools, and organizations.

There are many lenses through which we can take a more in-depth look to gain more context on the impact complacency has on growth and improvement. Take test scores for example. If a district or school traditionally has high achievement and continues to do so the rule of thumb is that no significant change is needed. Just because a school or educator might be “good” at something doesn’t equate to the fact that change isn’t required in other areas. It is also important to realize that someone else can view one’s perception of something being good in an entirely different light. Growth in all aspects of school culture is something that has to be the standard. It begins with getting out of actual and perceived comfort zones to truly start the process of improving school culture.

Image credit

Image credit

In a recent article Joani Junkala shares some great thoughts on the importance of stepping outside our comfort zones.

Are you comfortable where you are at professionally? What about your school, district, or organization? Where are opportunities for growth? By consistently reflecting on these questions a continual path to improvement can be paved. Questions lay the path forward. Actions are what get you to where you want to be.

Have you ever been complacent when it comes to undertaking or performing a task? Of course, you have, as this is just a part of human nature. In our personal lives, complacency can result if we are happy or content with where we are. Maybe we don’t change our work out routines because we have gotten used to doing the same thing day in and day out. I know I love using the elliptical for cardio, but rarely use any setting beside manual. Or perhaps our diet doesn’t change as we have an affinity for the same types of foods, which might or might not be that good for us. So, what’s my point with all of this? It is hard to grow and improve if one is complacent. This is why we must always be open to finding comfort in growth. If we don’t, then things might very well never change.

The issue described above is not just prevalent in our personal lives. Complacency plagues many organizations as well. When we are in a state of relative comfort with our professional practice, it is often difficult to move beyond that zone of stability and dare I say, “easy” sailing. If it isn’t broke, then why fix it, right? Maybe we aren’t pushed to take on new projects or embrace innovative ideas. Or perhaps there is no external accountability to improve really. Herein lies the inherent challenge of taking on the status quo in districts, schools, and organizations.

There are many lenses through which we can take a more in-depth look to gain more context on the impact complacency has on growth and improvement. Take test scores for example. If a district or school traditionally has high achievement and continues to do so the rule of thumb is that no significant change is needed. Just because a school or educator might be “good” at something doesn’t equate to the fact that change isn’t required in other areas. It is also important to realize that someone else can view one’s perception of something being good in an entirely different light. Growth in all aspects of school culture is something that has to be the standard. It begins with getting out of actual and perceived comfort zones to truly start the process of improving school culture.

Image credit

Image creditIn a recent article Joani Junkala shares some great thoughts on the importance of stepping outside our comfort zones.

Stepping out of our comfort zone requires us to step outside of ourselves. If we are going to strive for progress, whether professionally or personally, we have to get comfortable with the idea of being uncomfortable. This isn’t easy for everyone. For someone like me, who is a self-prescribed introvert, this can be difficult. Stepping out of our comfort zone requires extra effort, energy, and sometimes forced experiences. It requires us to set aside our fear and be vulnerable. We have to be willing to try something new, different, difficult, or even something that’s never been done before. We have to put ourselves out there — trusting in ourselves and trusting others with our most vulnerable self. It’s a frightening thought. What if we get it wrong? What if we look silly? Will it be worth it in the end? Will I stand alone? What if I fail? Oh but, what if I succeed and evolve?Change begins with each and every one of us and spreads from there. Finding comfort in growth and ultimately improvement begins with being honest with ourselves. Let me be blunt for a minute. The truth is that there is no perfect lesson, project, classroom, school, district, teacher, or administrator. There is, however, the opportunity every day to get better. This is not to say that great things are not happening in education. They most definitely are. My point is that we can never let complacency detract us from continually pursuing a path to where our learners need us to be.

Are you comfortable where you are at professionally? What about your school, district, or organization? Where are opportunities for growth? By consistently reflecting on these questions a continual path to improvement can be paved. Questions lay the path forward. Actions are what get you to where you want to be.

Published on May 13, 2018 05:12

May 6, 2018

Tic Tack Toe in the Blended Classroom

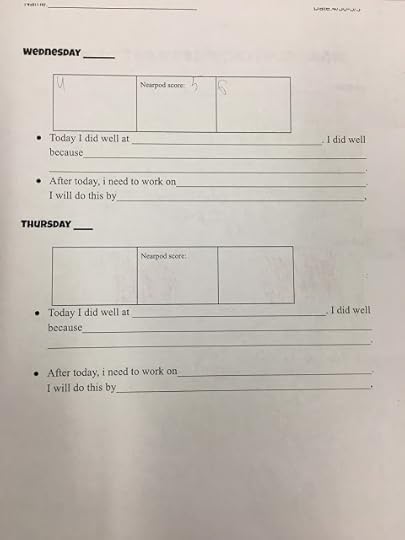

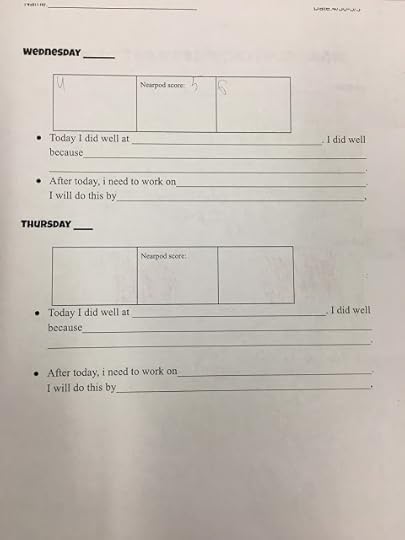

The other day I was conducting some learning walks with the administrative team at Wells Elementary School in the Cypress-Fairbanks Independent School District (CFISD). Throughout the school year, I have been assisting them with digital pedagogy as it relates to blended learning and the use of flex spaces. The primary goal has been to take a critical lens to instructional design with a focus on increasing the level of questioning, imparting relevance through authentic contexts and interdisciplinary connections, creating rigorous performance tasks, innovating assessment, and improving learner feedback. I cannot overstate the importance of getting the instructional design right first before throwing technology into the mix.

A secondary goal has been facilitating a transition from blended instruction to blended learning. This is not to say that the former is bad or ineffective, but it can be depending on whether or not the technology is just a direct substitute for low-level tasks or use is more passive as opposed to active. With this aside, there is a difference between the two, and it all has to with how the technology is being used and by whom. Blended instruction is what the teacher does with technology. Blended learning is where students use tech to have control over path, place, and pace. Herein lies the key to the practical use of flex spaces in education. The dynamic combination of pedagogically-sound blended learning and choice in either seating or moving around in flex spaces results in an environment where all kids can flourish and want to learn.

Over the course of the year, I have seen some much growth and improvement since the work began in August. My visits to this school have been inspiring as I have seen the future of education in the present. This is one of the main reasons that my daughter loves being a student here. Unlike our learning walks in the past, the teachers at Wells Elementary did not know I was going to be in the building on this particular day. The idea was to see if the goals for digital pedagogy and blended learning in flex spaces were well on their way to being accomplished.

I saw so many activities that warmed my heart where kids were authentically engaged in meaningful learning. However, stepping into Zaina Hussein’s 4th-grade classroom provided a perfect example of how the entire Wells community has evolved together to deliver fantastic learning opportunities for kids. As we walked in a Tic Tac Toe grid was displayed on the interactive whiteboard. Word on the street is that she “borrowed” this idea from Kendre Millburn, my daughter’s 5th-grade science teacher. If you are not familiar with this type of learning activity here is a description from the IRIS Center out of Vanderbilt University:

I was so mesmerized by the structure of the lesson and the engagement of the learners that I almost missed what possibly could have been the best part of the class – an opportunity to reflect. Costa & Kallick (2008) share why reflection is a critical component of the learning process:

It is important to understand the convergence of so many elements present in the examples above that align with sound instructional design and real blended learning. Learners had a certain amount of control over path, pace, and place thanks to using flex spaces and the Tic Tac Toe activity that incorporated blended elements. Student agency was also evident. This is a hallmark of a well-structured blended learning activity, which is why I was so pleased to see choice (Tic Tac Toe activity, flex seating) and voice (reflection) incorporated.

Over the course of the school year, I have seen so many exemplary blended learning activities implemented by Wells Elementary teachers across all grade levels during my time there as an instructional and leadership coach. I cannot commend their progress and success enough, but I would be remiss if I did not add how helpful the entire administrative team has been. They all have provided unwavering support to their teachers while also learning alongside them. When an entire school believes in different and better, takes collective action, grows together, and has the evidence to show improvement the result is efficacy.

Follow the learning adventures at Wells Elementary on Twitter at #ExploreWells.

A secondary goal has been facilitating a transition from blended instruction to blended learning. This is not to say that the former is bad or ineffective, but it can be depending on whether or not the technology is just a direct substitute for low-level tasks or use is more passive as opposed to active. With this aside, there is a difference between the two, and it all has to with how the technology is being used and by whom. Blended instruction is what the teacher does with technology. Blended learning is where students use tech to have control over path, place, and pace. Herein lies the key to the practical use of flex spaces in education. The dynamic combination of pedagogically-sound blended learning and choice in either seating or moving around in flex spaces results in an environment where all kids can flourish and want to learn.

Over the course of the year, I have seen some much growth and improvement since the work began in August. My visits to this school have been inspiring as I have seen the future of education in the present. This is one of the main reasons that my daughter loves being a student here. Unlike our learning walks in the past, the teachers at Wells Elementary did not know I was going to be in the building on this particular day. The idea was to see if the goals for digital pedagogy and blended learning in flex spaces were well on their way to being accomplished.

I saw so many activities that warmed my heart where kids were authentically engaged in meaningful learning. However, stepping into Zaina Hussein’s 4th-grade classroom provided a perfect example of how the entire Wells community has evolved together to deliver fantastic learning opportunities for kids. As we walked in a Tic Tac Toe grid was displayed on the interactive whiteboard. Word on the street is that she “borrowed” this idea from Kendre Millburn, my daughter’s 5th-grade science teacher. If you are not familiar with this type of learning activity here is a description from the IRIS Center out of Vanderbilt University:

Tic-tac-toe sometimes referred to as Think-tac-toe, is a method of offering students choices in the type of products they complete to demonstrate their knowledge. As in a traditional tic-tac-toe game, students are presented with a nine-cell table of options. The teacher should make sure that all options address the key concept or skill being learned. There are several variations on this method: 1. Students choose three product options that form a horizontal, vertical, or diagonal line. 2. Students choose one product choice from each row or from each column (without forming a straight line). 3. The teacher can create two or more versions to address the different readiness levels. To learn how to create an acnhor activity using a Tic Tack Toe board click HERE.I loved this activity for so many reasons. It incorporated choice, formative assessment, purposeful use of technology, and differentiation. All learners had to complete the middle box with the gold star emoji. The flame icons represented activities that were more difficult.

I was so mesmerized by the structure of the lesson and the engagement of the learners that I almost missed what possibly could have been the best part of the class – an opportunity to reflect. Costa & Kallick (2008) share why reflection is a critical component of the learning process:

Reflection has many facets. For example, reflecting on work enhances its meaning. Reflecting on experiences encourages insight and complex learning. We foster our growth when we control our learning, so some reflection is best done alone. Reflection is also enhanced, however, when we ponder our learning with others.

Reflection involves linking a current experience to previous learnings (a process called scaffolding). Reflection also involves drawing forth cognitive and emotional information from several sources: visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile. To reflect, we must act upon and process the information, synthesizing and evaluating the data. In the end, reflecting also means applying what we've learned to contexts beyond the original situations in which we learned something.

It is important to understand the convergence of so many elements present in the examples above that align with sound instructional design and real blended learning. Learners had a certain amount of control over path, pace, and place thanks to using flex spaces and the Tic Tac Toe activity that incorporated blended elements. Student agency was also evident. This is a hallmark of a well-structured blended learning activity, which is why I was so pleased to see choice (Tic Tac Toe activity, flex seating) and voice (reflection) incorporated.

Over the course of the school year, I have seen so many exemplary blended learning activities implemented by Wells Elementary teachers across all grade levels during my time there as an instructional and leadership coach. I cannot commend their progress and success enough, but I would be remiss if I did not add how helpful the entire administrative team has been. They all have provided unwavering support to their teachers while also learning alongside them. When an entire school believes in different and better, takes collective action, grows together, and has the evidence to show improvement the result is efficacy.

Follow the learning adventures at Wells Elementary on Twitter at #ExploreWells.

Published on May 06, 2018 03:11

April 29, 2018

Preparing Learners for the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Do you like change? If you do, then living in the present is an exhilarating experience. For those who don’t, buckle up as we are only going to see unprecedented innovations at exponential rates involving technology. You can’t run or hide from it. The revolution, or evolution depending on your respective lens, of our world, will transform everything as we know it. We must adapt, but more importantly, prepare our learners for a bold new world that is totally unpredictable. Welcome to the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

In Learning Transformed, my co-author Tom Murray and I looked in detail at the disruptive changes we are all seeing currently, but also those that are yet to come. Below provides a synopsis of the book:

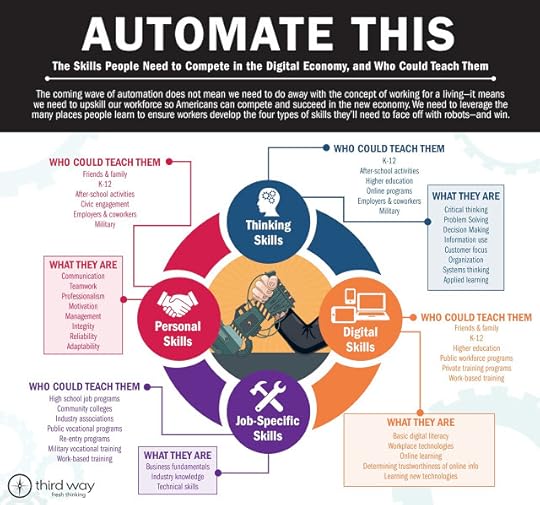

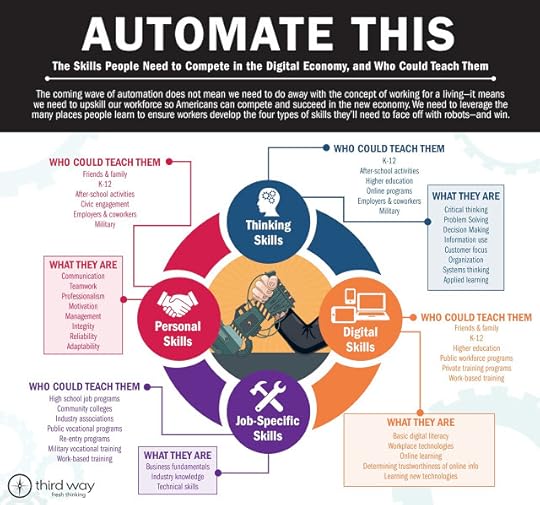

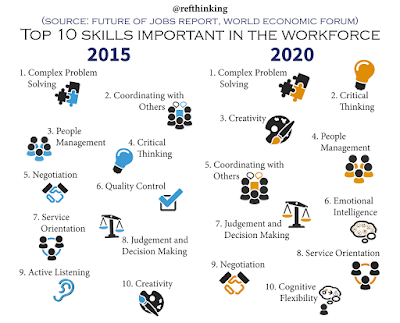

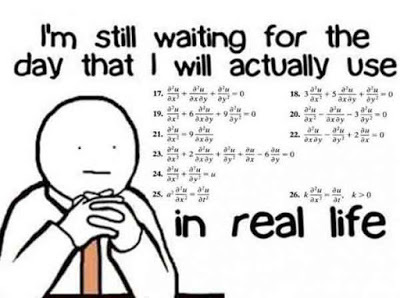

There are two images that come to mind that represent the need to reflect on where education is at in order to move to where it needs to be. The first one below pulled from an article titled Automate This: Building the Perfect 21st-Century Worker, represents the skills our learners will need to compete in a more automated world.

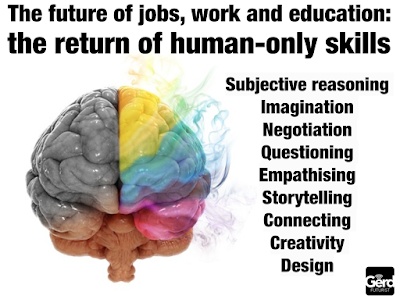

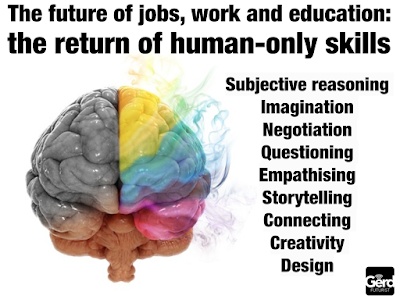

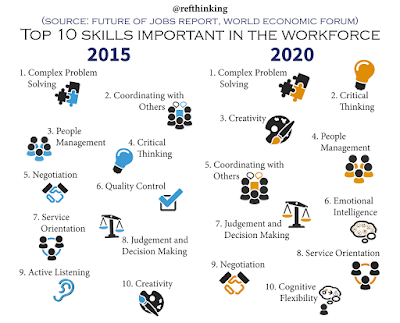

The second image comes courtesy of futurist Gerd Leonhard. This image is a simple, yet powerful reminder of the critical role soft skills and qualities that cannot be measured with traditional metrics will play in preparing learners for success during the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

As Tom and I state in Learning Transformed, “To prepare students for their world of work tomorrow, we must transform their learning today.” Skills are important, but we need to nurture competent learners who can think divergently, exhibit empathy, ask more questions than seek answers, and empower them to own their learning. It begins with taking a critical lens to our work followed by active reflection to determine if we are on the right path. However, it is important to understand that paths can and should readily change and that there might be multiple paths taken to get our kids to where they need to be. Are your learners prepared for the Fourth Industrial Revolution?

In Learning Transformed, my co-author Tom Murray and I looked in detail at the disruptive changes we are all seeing currently, but also those that are yet to come. Below provides a synopsis of the book:

Today’s pace of technological change is staggering, and the speed of current breakthroughs has no historical precedent. Consumers may seem well-versed with the latest personal gadgets, yet growth in artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, autonomous vehicles, the Internet of Things (IoT), and nanotechnology remains hardly known except to technology gurus who live and breathe ones and zeros. The coming interplay of such technologies from both physical and virtual worlds will make the once unthinkable, possible.

We believe that we are in the first few days of the next Industrial Revolution and that the coming age will systematically shift the way we live, work, and connect to and with one another. It will affect the very essence of the way humans experience the world. Although the 2000s brought with them significant change in how we utilize technology to interact with the world around us, the coming transformational change will be unlike anything mankind has ever experienced (Schwab, 2016).

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, toward which we are facing as a society, is still in its infancy but growing exponentially. Advances in technology are disrupting almost every industry and in almost every country. No longer do natural or political borders significantly reduce the acceleration of change.

Today, we are taking our first steps into the Fourth Industrial Revolution, created by the fusion of technologies that overlap physical, biological, and digital ecosystems. Known to some as Industry 4.0, these possibilities have been defined as “the next phase in the digitization of the manufacturing sector, driven by four disruptions: the astonishing rise in data volumes, computational power, and connectivity; the emergence of analytics and business-intelligence capabilities; new forms of human-machine interaction such as touch interfaces and augmented-reality systems; and improvements in transferring digital instructions to the physical world, such as advanced robotics and 3-D printing” (Baur & Wee, 2015). Such systems of automation enable intelligence to monitor the physical world, replicate it virtually, and make decisions about the process moving forward. In essence, machines now have the ability to think, problem solve, and make critical decisions. In this era, the notion of big data and data analytics will drive decision-making.To prepare learners for success during the fourth, or even fifth, industrial revolution the notion of education has to change at scale. If all of the change we are seeing has taught us one major lesson it is that schools must prepare kids to do anything, not something. Having current and future generations go through the motions and “do” school just won’t cut it. Just because it worked for us as adults, does not mean it works or even serves, well for our learners. The transition to the Fourth Industrial Revolution does not spell doom and gloom for society as we know it. The idea here is to be proactive, not reactive, and to understand where opportunities lie for growth and improvement in education systems across the globe.

There are two images that come to mind that represent the need to reflect on where education is at in order to move to where it needs to be. The first one below pulled from an article titled Automate This: Building the Perfect 21st-Century Worker, represents the skills our learners will need to compete in a more automated world.

The second image comes courtesy of futurist Gerd Leonhard. This image is a simple, yet powerful reminder of the critical role soft skills and qualities that cannot be measured with traditional metrics will play in preparing learners for success during the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

As Tom and I state in Learning Transformed, “To prepare students for their world of work tomorrow, we must transform their learning today.” Skills are important, but we need to nurture competent learners who can think divergently, exhibit empathy, ask more questions than seek answers, and empower them to own their learning. It begins with taking a critical lens to our work followed by active reflection to determine if we are on the right path. However, it is important to understand that paths can and should readily change and that there might be multiple paths taken to get our kids to where they need to be. Are your learners prepared for the Fourth Industrial Revolution?

Published on April 29, 2018 05:59

April 22, 2018

Cognitive Flexibility: Paving the Way For Learner Success

A few years back the World Economic Forum came out with an article titled The 10 skills you need to thrive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The opening two paragraphs sum up the point of the piece nicely:

The image above shows the skills that will be most in demand in 2020 and probably well beyond. After reading this article I was extremely interested in how schools and educators provide opportunities for learners to not only acquire these skills but also illustrate competence in how they are applied. Some of the skills and how leaners can demonstrate competency are self-explanatory. Others are not. This led me to focus on one skill in particular that crept onto the list at number 10 – cognitive flexibility. What does this skill entail? Below is a good definition from the University of Miami:

Design learning activities the support divergent thinking where learners demonstrate understanding in creative and non-conventional ways.Empower students to identify a solution and then come up with a workable solution in a makerspace.Allow students to explore a topic of interest in OpenCourseware and then demonstrate what they have learned in non-traditional ways (see IOCS).Implement personalized learning opportunities where students think critically, openly explore, and then do using their own intuitive ideas to learn in powerful ways.Engage students in a real-world application in unanticipated situations where they use their knowledge to tackle problems that have more than one solution. Provide pathways for students to transfer learning to a new context.

How we prepare our learners for the new world of work has to be a uniform focus for all schools. The key to future-proofing education and learning is to get kids to think by engaging them in tasks that develop cognitive flexibility.

By 2020, the Fourth Industrial Revolution will have brought us advanced robotics and autonomous transport, artificial intelligence and machine learning, advanced materials, biotechnology, and genomics.

These developments will transform the way we live, and the way we work. Some jobs will disappear, others will grow and jobs that don’t even exist today will become commonplace. What is certain is that the future workforce will need to align its skillset to keep pace.

The image above shows the skills that will be most in demand in 2020 and probably well beyond. After reading this article I was extremely interested in how schools and educators provide opportunities for learners to not only acquire these skills but also illustrate competence in how they are applied. Some of the skills and how leaners can demonstrate competency are self-explanatory. Others are not. This led me to focus on one skill in particular that crept onto the list at number 10 – cognitive flexibility. What does this skill entail? Below is a good definition from the University of Miami:

Cognitive flexibility is the ability to shift our thoughts and adapt our behavior to the changing environment. In other words, it’s one’s ability to disengage from a previous task and respond effectively to a new one. It’s a faculty that most of us take for granted, yet an essential skill to navigate life.Spiro & Jehn (1990, P. 65) provide another look at the skill:

By cognitive flexibility, we mean the ability to spontaneously restructure one’s knowledge, in many ways, in adaptive response to radically changing situational demands.Both definitions seamlessly align with Quad D learning based on the Rigor Relevance Framework as described below:

Students have the competence to think in complex ways and to apply their knowledge and skills they have acquired. Even when confronted with perplexing unknowns, students are able to use extensive knowledge and skill to create solutions and take action that further develops their skills and knowledge.In my mind, cognitive flexibility might be the most important skill on the list as it incorporates so many of the others in some form or another. Below are a few ideas and strategies on how to help learners develop this important skill:

Design learning activities the support divergent thinking where learners demonstrate understanding in creative and non-conventional ways.Empower students to identify a solution and then come up with a workable solution in a makerspace.Allow students to explore a topic of interest in OpenCourseware and then demonstrate what they have learned in non-traditional ways (see IOCS).Implement personalized learning opportunities where students think critically, openly explore, and then do using their own intuitive ideas to learn in powerful ways.Engage students in a real-world application in unanticipated situations where they use their knowledge to tackle problems that have more than one solution. Provide pathways for students to transfer learning to a new context.

How we prepare our learners for the new world of work has to be a uniform focus for all schools. The key to future-proofing education and learning is to get kids to think by engaging them in tasks that develop cognitive flexibility.

Published on April 22, 2018 10:05

April 15, 2018

Shifting from Passive to Active Learning

“Nothing could be more absurd than an experiment in which computers are placed in a classroom where nothing else is changed.” - Seymour Papert

When it comes to improving outcomes in the digital age, efficacy matters more than ever. Billions of dollars are spent across the world on technology with the hopes that it will lead to better results. Tom Murray and I shared this thought in Learning Transformed:

As I have said for years, pedagogy trumps technology. This simple concept can be readily applied to how devices are being used in classrooms. In Learning Transformed my co-author Tom Murray and I discussed in detail how technology can be an accelerant for learning. There was a specific reason that this was a focus near the end of our book and not in the beginning. Going back to the sage advice of William Horton we stressed the need to improve pedagogy first and foremost. Improvement lies in our ability as schools and educators to move away from broad claims and opinions to showing actual evidence aligned to good research. This is why efficacy through a Return on Instruction (ROI) is equally as important.

As technology continues to change so must instructional techniques, especially assessment. A robust pedagogical foundation compels us to ensure there is a shift from passive to active learning when it comes to devices in the classroom. Passive learning with devices involves the consumption of information and low-level and engagement instructional techniques such as taking notes, reading, and digital worksheets. On the other hand, active learning empowers students through meaningful activities where they actively apply what has been learned in authentic ways. Are learners in your school(s) using devices passively or actively?

There is a vast amount of research to support why learners should actively use devices. Below is a summary curated by Jay Lynch:

Passive learning, as well as digital drill and kill, will not improve outcomes. Additionally, our learners need opportunities to develop digital competencies to thrive in a rapidly changing world. Investing in devices only matters if they are used in powerful ways that represent an improvement on what has been done in the past. Knowing is important, but being able to show understanding is what we need to empower our learners to do, especially when it comes to technology.

When it comes to improving outcomes in the digital age, efficacy matters more than ever. Billions of dollars are spent across the world on technology with the hopes that it will lead to better results. Tom Murray and I shared this thought in Learning Transformed:

Educational technology is not a silver bullet. Yet year after year, districts purchase large quantities of devices, deploy them on a large scale, and are left hoping the technology will have an impact. Quite often, they’re left wondering why there was no change in student engagement or achievement after large financial investments in devices. Today’s devices are powerful tools. At the cost of only a few hundred dollars, it’s almost possible to get more technological capacity than was required to put people on the moon. Nevertheless, the devices in tomorrow’s schools will be even more robust. With that in mind, it’s important to understand that the technology our students are currently using in their classrooms is the worst technology they will ever use moving forward. As the technology continues to evolve, the conversation must remain focused on learning and pedagogy—not on devices.Unfortunately, technology is not a magic wand that will automatically empower learners to think critically, solve complex problems, or close achievement gaps. These outcomes rely on taking a critical lens to pedagogical techniques to ensure that they evolve so that technology can begin to support and ultimately enhance instruction. If the former (pedagogy) isn’t solid, then all the technology in the world won’t make a difference. As William Horton states, “Unless you get the instructional design right, technology can only increase the speed and certainty of failure.”

As I have said for years, pedagogy trumps technology. This simple concept can be readily applied to how devices are being used in classrooms. In Learning Transformed my co-author Tom Murray and I discussed in detail how technology can be an accelerant for learning. There was a specific reason that this was a focus near the end of our book and not in the beginning. Going back to the sage advice of William Horton we stressed the need to improve pedagogy first and foremost. Improvement lies in our ability as schools and educators to move away from broad claims and opinions to showing actual evidence aligned to good research. This is why efficacy through a Return on Instruction (ROI) is equally as important.

As technology continues to change so must instructional techniques, especially assessment. A robust pedagogical foundation compels us to ensure there is a shift from passive to active learning when it comes to devices in the classroom. Passive learning with devices involves the consumption of information and low-level and engagement instructional techniques such as taking notes, reading, and digital worksheets. On the other hand, active learning empowers students through meaningful activities where they actively apply what has been learned in authentic ways. Are learners in your school(s) using devices passively or actively?

There is a vast amount of research to support why learners should actively use devices. Below is a summary curated by Jay Lynch:

Robust research has found that learning is more durable and lasting when students are cognitively engaged in the learning process. Long-term retention, understanding, and transfer are the result of mental work on the part of learners who are engaged in active sense-making and knowledge construction. Accordingly, learning environments are most effective when they elicit effortful cognitive processing from learners and guide them in constructing meaningful relationships between ideas rather than encouraging passive recording of information (deWinstanley et al., 2003; Clark & Mayer, 2008; Mayer, 2011).

Researchers have consistently found that higher student achievement and engagement are associated with instructional methods involving active learning techniques (Freeman et al., 2004 and McDermott et al., 2014).

The primary takeaway from research on active learning is that student learning success depends much less on what instructors do than what they ask their students to do (Halpern & Hakel, 2003).The natural shift when it comes to device use by students is more active than passive learning. Here is a great guiding question - How are students empowered to learn with technology in ways that they couldn’t without it? It is really about how students use devices to create artifacts of learning that demonstrate conceptual mastery through relevant application and evaluation. What might this look like you ask? Give kids challenging problems to solve that have more than one right answer and let them use technology to show that they understand. When doing so let them select the right tool for the task at hand. This is the epitome of active learning in my opinion.

Passive learning, as well as digital drill and kill, will not improve outcomes. Additionally, our learners need opportunities to develop digital competencies to thrive in a rapidly changing world. Investing in devices only matters if they are used in powerful ways that represent an improvement on what has been done in the past. Knowing is important, but being able to show understanding is what we need to empower our learners to do, especially when it comes to technology.

Published on April 15, 2018 06:03

April 8, 2018

Relevance is the Fuel of Learning

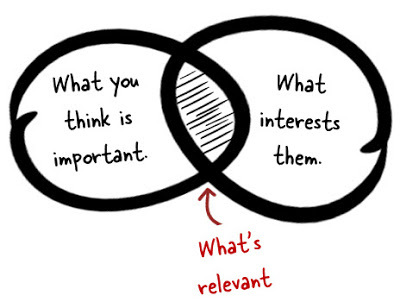

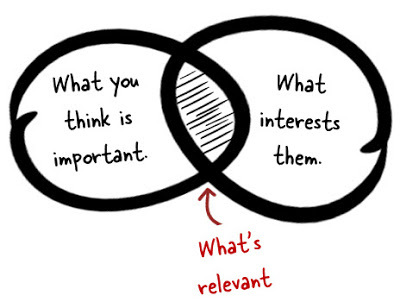

In a previous blog post, I wrote about the importance of focusing on the why as it relates to learning. Here is a piece of my thinking that I shared:

Image credit

Image credit

Diverse Learners respond well to relevant and contextual learning. This improves memory, both short-term, and long-term, which is all backed by science. Sara Briggs sums it up nicely:

Image credit

Image credit

When it is all said and done, if a lesson or project is relevant students will be able to tell you:

What they learnedWhy they learned itHow they will use it

Without relevance, learning many concepts don’t make sense to students. The many benefits speak for themselves, which compels all of us to ensure that this becomes a mainstay in daily pedagogy.

The why matters more than ever in the context of schools and education. What all one must do is step into the shoes of a student. If he or she does not truly understand why they are learning what is being taught, the chances of improving outcomes and success diminish significantly. Each lesson should squarely address the why. What and how we assess carries little to no weight in the eyes of our students if they don’t understand and appreciate the value of the learning experience.The paragraph above represents the importance of making the educational experience relevant. In a nutshell, relevance is the purpose of learning. If it is absent from any activity or lesson, many, if not all, students are less motivated to learn and ultimately achieve. Research on the underlying elements that drive student motivation validates how essential it is to establish relevant contexts. Kember et al. (2008) conducted a study where 36 students were interviewed about aspects of the teaching and learning environment that motivated or demotivated their learning. They found the following:

"One of the most important means of motivating student learning was to establish relevance. It was a critical factor in providing a learning context in which students construct their understanding of the course material. The interviewees found that teaching abstract theory alone was demotivating. Relevance could be established through showing how theory can be applied in practice, creating relevance to local cases, relating the material to everyday applications, or finding applications in current newsworthy issues."Getting kids to think is excellent, but if they don’t truly understand how this thinking will help them, do they value learning? The obvious answer is no. However, not much legwork is needed to add meaning to any lesson, project, or assignment. Relevance begins with students acquiring knowledge and applying it to multiple disciplines to see how it connects to the bigger picture. It becomes even more embedded in the learning process when students apply what has been learned to real-world predictable and ultimately unpredictable situations, resulting in the construction of new knowledge. Thus, a relevant lesson or task empowers learners to use their knowledge to tackle real-world problems that have more than one solution.

Image credit

Image creditDiverse Learners respond well to relevant and contextual learning. This improves memory, both short-term, and long-term, which is all backed by science. Sara Briggs sums it up nicely:

"Research shows that relevant learning means effective learning and that alone should be enough to get us rethinking our lesson plans (and school culture for that matter). The old drill-and-kill method is neurologically useless, as it turns out. Relevant, meaningful activities that both engage students emotionally and connect with what they already know are what help build neural connections and long-term memory storage."In the words of Will Durant based on Aristotle’s work,” “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” The point here is that consistent efforts must be made to integrate interdisciplinary connections and authentic contexts to impart value to our learners. Relevance must be student based: the student’s life, the student’s family, and friends, the student’s community, the world today, current events, etc.

Image credit

Image creditWhen it is all said and done, if a lesson or project is relevant students will be able to tell you:

What they learnedWhy they learned itHow they will use it

Without relevance, learning many concepts don’t make sense to students. The many benefits speak for themselves, which compels all of us to ensure that this becomes a mainstay in daily pedagogy.

Published on April 08, 2018 05:54

April 1, 2018

Ownership Through Inquiry

As a child, I was enamored by nature. My twin brother and I were always observing and collecting any and all types of critters we could get our hands on. Growing up in a rural area of Northwestern New Jersey made it quite easy to seek out and find different plants and animals on a daily basis. We would spend countless hours roaming around the woods, corn fields, ponds, and streams in our quest to study as much local life as possible. It’s no wonder that I eventually became a science teacher as my surroundings growing up played a major role in my eventual decision to go into the field of education.

To this day I still can’t believe how my mother tolerated us bringing an array of animals into the house. For years my brother and I were particularly interested in caterpillars. We would use encyclopedias and field guides to identify certain species that were native to our area. Through our research, we determined what each caterpillar ate and subsequently scoured trees, bushes, and other plants in our quest to collect, observe, and compare the differences between different species. We even kept journals with notes and sketches. When we were successful in locating these insects we then collected them in jars. Our research ensured that each species had the correct type of food as well as appropriate physical requirements to either make a chrysalis (butterflies) or cocoon (moths).

In the case of moths, some were in their cocoons for months. Hence, my brother and I stored these jars under our beds. At times we forgot that we had these living creatures under our beds until at night we heard sounds of them flapping their wings and moving around the jars after emerging from their cocoons. I can only imagine what my parents thought of this but am so thankful that they supported our inquiry in many ways from having encyclopedias available for research to providing us with the autonomy to harness our intrinsic motivation to learn. Through it all our observations led to questions and together with my brother and I worked to find answers. Even though we were not always successful in this endeavor, the journey was worth it. Questions and even more questions drove the inquiry process for both of us and from there we leveraged available resources and synthesized what we had learned.

Image credit

Image credit

The story above is a great example of how my brother and I embarked on an informal learning process driven by inquiry. We owned the process from start to finish and our parents acted as indirect facilities through their support and encouragement. Both inquiry and ownership of learning are not new concepts, although they are both thrown around interchangeably as of late, especially ownership. Deborah Voltz and Margaret Damiano-Lantz came up with this description in 1993:

To this day I still can’t believe how my mother tolerated us bringing an array of animals into the house. For years my brother and I were particularly interested in caterpillars. We would use encyclopedias and field guides to identify certain species that were native to our area. Through our research, we determined what each caterpillar ate and subsequently scoured trees, bushes, and other plants in our quest to collect, observe, and compare the differences between different species. We even kept journals with notes and sketches. When we were successful in locating these insects we then collected them in jars. Our research ensured that each species had the correct type of food as well as appropriate physical requirements to either make a chrysalis (butterflies) or cocoon (moths).

In the case of moths, some were in their cocoons for months. Hence, my brother and I stored these jars under our beds. At times we forgot that we had these living creatures under our beds until at night we heard sounds of them flapping their wings and moving around the jars after emerging from their cocoons. I can only imagine what my parents thought of this but am so thankful that they supported our inquiry in many ways from having encyclopedias available for research to providing us with the autonomy to harness our intrinsic motivation to learn. Through it all our observations led to questions and together with my brother and I worked to find answers. Even though we were not always successful in this endeavor, the journey was worth it. Questions and even more questions drove the inquiry process for both of us and from there we leveraged available resources and synthesized what we had learned.

Image credit

Image creditThe story above is a great example of how my brother and I embarked on an informal learning process driven by inquiry. We owned the process from start to finish and our parents acted as indirect facilities through their support and encouragement. Both inquiry and ownership of learning are not new concepts, although they are both thrown around interchangeably as of late, especially ownership. Deborah Voltz and Margaret Damiano-Lantz came up with this description in 1993:

Ownership of learning refers to the development of a sense of connectedness, active involvement, and personal investment in the learning process. This is important for all learners in that it facilitates understanding and retention and promotes a desire to learn.After reading this description I can’t help but see the alignment to the story I shared above. We learned not because we had to, but because we wanted to. Herein lies a potential issue in schools. Are kids learning because they are intrinsically empowered to or are they compelled to through compliance and conformity? The former results when learners have a real sense of ownership. There are many ways to empower kids to own their learning. All the rage as of late is how technology can be such a catalyst. In many cases this is true, but ownership can result if the conditions are established where kids inquire by way of their own observations and questions. WNET Education describes inquiry as follows:

"Inquiry" is defined as "a seeking for truth, information, or knowledge -- seeking information by questioning." Individuals carry on the process of inquiry from the time they are born until they die. Through the process of inquiry, individuals construct much of their understanding of the natural and human-designed worlds. Inquiry implies a "need or wants to know" premise. Inquiry is not so much seeking the right answer -- because often there is none -- but rather seeking appropriate resolutions to questions and issues.The first sentence ties in directly to the concept of ownership, but we also see how important are questions. This is why empowering learners to develop their own questions and then use an array of resources to process and share new knowledge or demonstrating an understanding of concepts are critical if ownership is the goal. The article from WNET explains why this is so important:

Effective inquiry is more than just asking questions. A complex process is involved when individuals attempt to convert information and data into useful knowledge. A useful application of inquiry learning involves several factors: a context for questions, a framework for questions, a focus on questions, and different levels of questions. Well-designed inquiry learning produces knowledge formation that can be widely applied.Ownership through inquiry is not as difficult as you might think if there is a common vision, language, expectation, and a commitment to student agency. The Rigor Relevance Framework represents a simple process to help educators and learners scaffold questions as part of the inquiry process while empowering kids to demonstrate understanding aligned with relevant contexts. By taking a critical lens to instructional design, improvement can happen now. Curiosity and passion reside in all learners. Inquiry can be used to tap into both of these elements and in the process, students will be empowered to own their learning.

Published on April 01, 2018 05:51

March 25, 2018

The Journey to Becoming an Author

I never imagined I would have authored or co-authored a book, let alone six. My unexpected journey began with a decision to give Twitter a try in 2009. This should never have happened either as I was convinced that any and all social media tools were a complete waste of my time and would not lead to any improvement in professional practice. Apparently, I was dead wrong on this assumption and quickly learned that Twitter in itself wasn’t a powerful tool, but instead, it was the conversations, ideas, resources, and passionate educators that connected with me. The rest is history.

As my mindset began to shift from one that focused on the “what ifs” instead of the “yeah buts,” my staff and I started to transform learning in our school to better meet the needs of our students. Social media not only gave us the inspiration but also empowered us to take action. It is important to note that we weren’t doing a bad job per se. The fact for us, like every other school on the planet, was that we could be better. In the beginning, we really weren’t sure what we were doing or whether it would lead to improved outcomes, but we did our best to align every innovative idea with research and sound pedagogy. Thanks to my amazing teachers, innovative changes began to take hold and outcomes improved in the process.

My essential role in the transformation efforts focused on helping to clarify a shared vision, supporting my teachers, showing efficacy, and celebrating success. Sharing why we were innovating coupled with how we were doing it and what the results were, gathered a great deal of attention that was unexpected at first. To this day I still remember sitting in a district administrator meeting in November 2009 when my secretary called to tell me that CBS New York City wanted to come to the high school and feature how we were using Twitter in the classroom to support learning. To say that I was floored by the interest from the largest media market in the world would be putting it mildly. This point in time was a catalyst for the eventual brandED strategy that evolved. I learned that social media was an incredible tool to tell our story, praise staff, and acknowledge the great work of my students.

Image credit

Image credit

Little did I know, or plan for that matter, that sharing our transformation efforts would lead to me becoming an author. This was not my intent or even a goal. One day in 2010 I received a Twitter message from Bill Ferriter asking if I would be interested in co-authoring a book with him and Jason Ramsden titled Communicating and Connecting with Social Media. My first thought was, “Heck no! I am no author.” Bill, the master teacher he is, reassured me that I could do this and would guide me through the writing process. Through his tutelage and many hours spent writing over weekends and breaks, the book took form. Thus, my author journey began all because of the consistent efforts to share the work of my teachers.

Shortly after this book came out, Solution Tree asked if I would work on another project. This one focused on a book for principals about teaching science, as this was where my experience was in the classroom. I agreed to take this on only if one of my teachers could co-author the book with me. This was just a small way of paying it forward since I would not have been in a position to author any books had it not been for the willingness of my teachers to embrace change and have the results to show efficacy.

My teachers and students, as well as the support I received from the district, helped me evolve into the unlikeliest of authors. Not only was I supported in writing books, but I was also encouraged to share our work at local and national events. I cannot even begin to explain the sense of pride I felt by being asked to present on the work occurring at my school. It was during one of these presentations at the National Association of Secondary School Principals Conference that I was asked by Corwin to consider writing Digital Leadership. At first, I said no as I really did not have the time needed to write a book all on my own. After some persistence on behalf of my acquisition editor, I later agreed and scheduled the majority of the writing during the summer months when my students and staff were off.

The publication of Digital Leadership in 2014 changed everything for me as the book performed exceptionally well and continues to do so. As a result, I was flooded with speaking requests and asked to write even more books, including Uncommon Learning. To this day I still can’t believe that anyone asks me to write a book. The time then came that I knew a decision on my future had to be made. Even though I was fully supported by my district and dedicated myself 100% to the school, I came to the conclusion that I was not going to be fair to my students, staff, or community shortly. It was at this time that I made the painful decision to leave the principalship.

You might be wondering what the actual point of this post was. As of late people have taken to social media to attack or discredit other educators who have written books while working in schools. My take on it is this. I am all for practitioners utilizing their time outside of classrooms and schools to write books that use research as a foundation while showing how their work and that of colleagues has improved teaching, learning, and leadership. There is nothing more inspiring, and practical for that matter, to read about what actually works in the face of the myriad of challenges that educators endure on a daily basis. There will never be enough books that lay out how efficacy can be achieved in the pursuit of providing all kids with an awesome learning experience.

There is a fine line here though. Authoring books should never conflict with, or have a negative impact on, professional responsibilities. It goes without saying that all writing and sharing of books by practitioners should happen outside of regular school hours or on weekends and breaks. My schedule as both a teacher and principal were jam packed so there was never aforethought about putting aside time to work on a book (or blog) that would take away from my contractual duties. Sharing during the school day also sends a potentially negative message to colleagues and staff.

Many people, like myself, never intended on becoming authors. It was an unintended consequence of sharing successes of others who are in the trenches every day. To this day I can’t thank my teachers, students, and district enough for not only believing in me but also empowering me to share the ideas and strategies that we put into practice. I hope more and more educators contribute to the field by authoring books that will add to the vast knowledge base already available while providing practical solutions to transform education.

As my mindset began to shift from one that focused on the “what ifs” instead of the “yeah buts,” my staff and I started to transform learning in our school to better meet the needs of our students. Social media not only gave us the inspiration but also empowered us to take action. It is important to note that we weren’t doing a bad job per se. The fact for us, like every other school on the planet, was that we could be better. In the beginning, we really weren’t sure what we were doing or whether it would lead to improved outcomes, but we did our best to align every innovative idea with research and sound pedagogy. Thanks to my amazing teachers, innovative changes began to take hold and outcomes improved in the process.

My essential role in the transformation efforts focused on helping to clarify a shared vision, supporting my teachers, showing efficacy, and celebrating success. Sharing why we were innovating coupled with how we were doing it and what the results were, gathered a great deal of attention that was unexpected at first. To this day I still remember sitting in a district administrator meeting in November 2009 when my secretary called to tell me that CBS New York City wanted to come to the high school and feature how we were using Twitter in the classroom to support learning. To say that I was floored by the interest from the largest media market in the world would be putting it mildly. This point in time was a catalyst for the eventual brandED strategy that evolved. I learned that social media was an incredible tool to tell our story, praise staff, and acknowledge the great work of my students.

Image credit

Image creditLittle did I know, or plan for that matter, that sharing our transformation efforts would lead to me becoming an author. This was not my intent or even a goal. One day in 2010 I received a Twitter message from Bill Ferriter asking if I would be interested in co-authoring a book with him and Jason Ramsden titled Communicating and Connecting with Social Media. My first thought was, “Heck no! I am no author.” Bill, the master teacher he is, reassured me that I could do this and would guide me through the writing process. Through his tutelage and many hours spent writing over weekends and breaks, the book took form. Thus, my author journey began all because of the consistent efforts to share the work of my teachers.

Shortly after this book came out, Solution Tree asked if I would work on another project. This one focused on a book for principals about teaching science, as this was where my experience was in the classroom. I agreed to take this on only if one of my teachers could co-author the book with me. This was just a small way of paying it forward since I would not have been in a position to author any books had it not been for the willingness of my teachers to embrace change and have the results to show efficacy.

My teachers and students, as well as the support I received from the district, helped me evolve into the unlikeliest of authors. Not only was I supported in writing books, but I was also encouraged to share our work at local and national events. I cannot even begin to explain the sense of pride I felt by being asked to present on the work occurring at my school. It was during one of these presentations at the National Association of Secondary School Principals Conference that I was asked by Corwin to consider writing Digital Leadership. At first, I said no as I really did not have the time needed to write a book all on my own. After some persistence on behalf of my acquisition editor, I later agreed and scheduled the majority of the writing during the summer months when my students and staff were off.

The publication of Digital Leadership in 2014 changed everything for me as the book performed exceptionally well and continues to do so. As a result, I was flooded with speaking requests and asked to write even more books, including Uncommon Learning. To this day I still can’t believe that anyone asks me to write a book. The time then came that I knew a decision on my future had to be made. Even though I was fully supported by my district and dedicated myself 100% to the school, I came to the conclusion that I was not going to be fair to my students, staff, or community shortly. It was at this time that I made the painful decision to leave the principalship.

You might be wondering what the actual point of this post was. As of late people have taken to social media to attack or discredit other educators who have written books while working in schools. My take on it is this. I am all for practitioners utilizing their time outside of classrooms and schools to write books that use research as a foundation while showing how their work and that of colleagues has improved teaching, learning, and leadership. There is nothing more inspiring, and practical for that matter, to read about what actually works in the face of the myriad of challenges that educators endure on a daily basis. There will never be enough books that lay out how efficacy can be achieved in the pursuit of providing all kids with an awesome learning experience.

There is a fine line here though. Authoring books should never conflict with, or have a negative impact on, professional responsibilities. It goes without saying that all writing and sharing of books by practitioners should happen outside of regular school hours or on weekends and breaks. My schedule as both a teacher and principal were jam packed so there was never aforethought about putting aside time to work on a book (or blog) that would take away from my contractual duties. Sharing during the school day also sends a potentially negative message to colleagues and staff.

Many people, like myself, never intended on becoming authors. It was an unintended consequence of sharing successes of others who are in the trenches every day. To this day I can’t thank my teachers, students, and district enough for not only believing in me but also empowering me to share the ideas and strategies that we put into practice. I hope more and more educators contribute to the field by authoring books that will add to the vast knowledge base already available while providing practical solutions to transform education.

Published on March 25, 2018 05:59

March 18, 2018

Teachers are the Driving Force of Change

During virtually every keynote, presentation, or workshop that I give, the topic of change is very much a part of it. Leading the effort to uproot the status quo and prepare kids for anything as opposed to something is easier said than done. As Tom Murray and I state in Learning Transformed, "To prepare students for their world of work tomorrow, we must transform their learning today." Great progress is being made in classrooms and schools across the world. As technology has continued to evolve at an exponential rate we have seen passionate educators begin to embrace and implement innovative strategies to better meet the needs of learners today.

As a result, isolated pockets of excellence have emerged in virtually every school. Don't get me wrong, this is great. I am all for progress and a move from business as usual to unusual in pursuit of learning that will prepare kids with the critical competencies to excel in a disruptive world. However, we cannot be satisfied with just a few pockets as every student deserves an amazing learning experience. Change at scale is a collective effort where we must leverage the unique assets embedded in every position and at all levels. As the saying goes, there is no "I" in team.

Now granted, building and district leaders play a huge role in supporting change and ensuring success. Their role is to build on these successes while removing obstacles, establishing a shared vision, developing parameters for accountability around growth, evaluating if efficacy has been achieved, and reflecting on the entire process. Reflection could very well be the most important aspect of the change process as there will either be validation or the identification of needed elements to ensure success. Since there is always room for improvement in the education profession these leaders need to take action on the broader issues to improve the culture of learning at scale.

The most important group, however, rarely gets the credit they rightfully deserve. The most impactful change doesn't come from people with a title, power, or authoritative position in education. It happens at the ground level with our teachers as it is they who have to implement ideas for the direct betterment of students. Think about this for a second. If it weren't for our teachers embracing broader ideas and putting them into practice would any change in schools actually occur? The simple answer is no.

Image credit

Image credit

When I think back to all of the success that we had at my school it wasn't because of me or the fact that I was the principal. Sure, I played my part as described previously in this post, but my role in the bigger picture was a small one. It was because my teachers believed we could be better for our learners and as a result, they embraced innovative ideas. This brings me to a critical point. We must celebrate the invaluable leadership of our teachers while also working tirelessly to create the conditions where they are empowered to be the change that is needed.

Never say you are "just a teacher." Let your actions, not a role, define you. The change our schools need at scale can only be ushered in by our teachers. If you are in a typical administrative position to make that happen then become a beacon of support, not a roadblock to progress. We need bold administrators to enlighten others who are unwilling or scared to embrace innovative ideas that go against the status quo. Only by working together can both groups transform learning for all kids now and well into the future.

As a result, isolated pockets of excellence have emerged in virtually every school. Don't get me wrong, this is great. I am all for progress and a move from business as usual to unusual in pursuit of learning that will prepare kids with the critical competencies to excel in a disruptive world. However, we cannot be satisfied with just a few pockets as every student deserves an amazing learning experience. Change at scale is a collective effort where we must leverage the unique assets embedded in every position and at all levels. As the saying goes, there is no "I" in team.

Now granted, building and district leaders play a huge role in supporting change and ensuring success. Their role is to build on these successes while removing obstacles, establishing a shared vision, developing parameters for accountability around growth, evaluating if efficacy has been achieved, and reflecting on the entire process. Reflection could very well be the most important aspect of the change process as there will either be validation or the identification of needed elements to ensure success. Since there is always room for improvement in the education profession these leaders need to take action on the broader issues to improve the culture of learning at scale.

The most important group, however, rarely gets the credit they rightfully deserve. The most impactful change doesn't come from people with a title, power, or authoritative position in education. It happens at the ground level with our teachers as it is they who have to implement ideas for the direct betterment of students. Think about this for a second. If it weren't for our teachers embracing broader ideas and putting them into practice would any change in schools actually occur? The simple answer is no.

Image credit