David McRaney's Blog, page 37

September 7, 2011

You Are Not So Smart – The Official Movie Trailer (for the book)

This is the first of two trailers for the book. I wanted the first video released to be something which could stand alone, something which would keep the tone and approach of the book. I also wanted it to be worth watching even if it wasn’t promoting something. I love it so much.

I hired Plus3 Productions to make it. From the beginning, I knew I wanted kenetic typography, and they delivered. Thank you! You should hire them to make something cool.

The trailer is all about procrastination, one of the most popular posts on the blog.

I hope you enjoy it, and if you do, please share it.

August 21, 2011

The Illusion of Asymmetric Insight

The Misconception: You celebrate diversity and respect others’ points of view.

The Truth: You are driven to create and form groups and then believe others are wrong just because they are others.

Source: "Lord of the Flies," 1963, Two Arts Ltd.

In 1954, in eastern Oklahoma, two tribes of children nearly killed each other.

The neighboring tribes were unaware of each other’s existence. Separately, they lived among nature, played games, constructed shelters, prepared food – they knew peace. Each culture developed its own norms and rules of conduct. Each culture arrived at novel solutions to survival-critical problems. Each culture named the creeks and rocks and dangerous places, and those names were known to all. They helped each other and watched out for the well-being of the tribal members.

Scientists stood by, watchful, scribbling notes and whispering. Much nodding and squinting took place as the tribes granted to anthropology and psychology a wealth of data about how people build and maintain groups, how hierarchies are established and preserved. They wondered, the scientists, what would happen if these two groups were to meet.

These two tribes consisted of 22 boys, ages 11 and 12, whom psychologist Muzafer Sherif brought together at Oklahoma’s Robber’s Cave State Park. He and his team placed the two groups on separate buses and drove them to a Boy Scout Camp inside the park – the sort with cabins and caves and thick wilderness. At the park, the scientists put the boys into separate sides of the camp about a half-mile apart and kept secret the existence and location of the other group. The boys didn’t know each other beforehand, and Sherif believed putting them into a new environment away from their familiar cultures would encourage them to create a new culture from scratch.

He was right, but as those cultures formed and met something sinister presented itself. One of the behaviors which pushed and shoved its way to the top of the boys’ minds is also something you are fending off at this very moment, something which is making your life harder than it ought to be. We’ll get to all that it in a minute. First, let’s get back to one of the most telling and frightening experiments in the history of psychology.

Sherif and his colleagues pretended to be staff members at the camp so they could record, without interfering, the natural human drive to form tribes. Right away, social hierarchies began to emerge in which the boys established leaders and followers and special roles for everyone in between. Norms spontaneously generated. For instance, when one boy hurt his foot but didn’t tell anyone until bedtime, it became expected among the group that Rattlers didn’t complain. From then on members waited until the day’s work was finished to reveal injuries. When a boy cried, the others ignored him until he got over it. Regulations and rituals sprouted just as quickly. For instance, the high-status members, the natural leaders, in both groups came up with guidelines for saying grace during meals and correct rotations for the ritual. Within a few days their initially arbitrary suggestions became the way things were done, and no one had to be prompted or reprimanded. They made up games and settled on rules of play. They embarked on projects to clean up certain areas and established chains of command. Slackers were punished. Over achievers were praised. Flags were created. Signs erected.

Soon, the two groups began to suspect they weren’t alone. They would find evidence of others. They found cups and other signs of civilization in places they didn’t remember visiting. This strengthened their resolve and encouraged the two groups to hold tighter to their new norms, values, rituals and all the other elements of the shared culture. At the end of the first week, the Rattlers discovered the others on the camp’s baseball diamond. From this point forward both groups spent most of their time thinking about how to deal with their new-found adversaries. The group with no name asked about the outsiders. When told the other group called themselves the Rattlers, they elected a baseball captain and asked the camp staff if they could face off in a game with the enemy. They named their baseball team the Eagles after an animal they thought ate snakes.

From the study, the boys face each other for the first time

Sherif and his colleagues had already planned on pitting the groups against each other in competitive sports. They weren’t just researching how groups formed but also how they acted when in competition for resources. The fact the boys were already becoming incensed over the baseball field seemed to fall right in line with their research. So, the scientists proceeded with stage two. The two tribes were overjoyed to learn they would not only play baseball, but compete in tug-of-war, touch football, treasure hunts and other summer-camp-themed rivalry. The scientists revealed a finite number of prizes. Winners would receive one of a handful of medals or knives. When the boys won the knives, some would kiss them before rushing to hide the weapons from the other group.

Sherif noted the two groups spent a lot of time talking about how dumb and uncouth the other side was. They called them names, lots of names, and they seemed to be preoccupied every night with defining the essence of their enemies. Sherif was fascinated by this display. The two groups needed the other side to be inferior once the competition for limited resources became a factor, so they began defining them as such. It strengthened their identity to assume the identity of the enemy was a far cry from their own. Everything they learned about the other side became an example of how not to be, and if they did happen to see similarities they tended to be ignored.

The researchers collected data and discussed findings while planning the next series of activities, but the boys made other plans. The experiment was about to spiral out of control, and it started with the Eagles.

Some of the Eagles boys discovered the Rattlers’ flag standing unguarded on the baseball field. They discussed what to do and decided it should be ripped from the ground. Once they had it, a possession of the enemy, a symbol of their tribe, they decided to burn it. They then put its scorched remains back in place and sang Taps. Later, the Rattlers saw the atrocity and organized a raid in which they stole the Eagles’ flag and burned it as payback. When the Eagles discovered the revenge burning, the leader issued a challenge – a face off. The two leaders then met with their followers watching and prepared to fight, but the scientists intervened. That night, the Rattlers dressed in war paint and raided the Eagles’ cabins, turning over beds and tearing apart mosquito netting. The staff again intervened when the two groups started circling and gathering rocks. The next day, the Rattlers painted one of the Eagle boy’s stolen blue jeans with insults and paraded it in front of the enemy’s camp like a flag. The Eagles waited until the Rattlers were eating and conducted a retaliatory raid and then ran back to their cabin to set up defenses. They filled socks with rocks and waited. The camp staff, once again, intervened and convinced the Rattlers not to counterattack. The raids continued, and the interventions too, and eventually the Rattlers stole the Eagles knives and medals. The Eagles, determined to retrieve them, formed an organized war party with assigned roles and planned tactical maneuvers. The two groups finally fought in open combat. The scientists broke up the fights. Fearing the two tribes might murder someone, they moved the groups’ camps away from each other.

You probably suspected this was where the story was headed. You know it is possible in the right conditions that people, even children, might revert to savages. You know about the instant-coffee-version of cultures too. You remember high school. You’ve worked in a cubicle farm. You’ve watched Stephen King movies. People in new situations instinctively form groups. Those groups develop their own language quirks, in-jokes, norms, values and so on. You’ve probably suspected zombies, or bombs, or economic collapse would lead to a battle over who runs Bartertown. In this study, all they had to do was introduce competition for resources and summer camp became Lord of the Flies.

What you may not have noticed though is how much of this behavior is gurgling right below the surface of your consciousness day-to-day. You aren’t sharpening spears, but at some level you are contemplating your place in society, contemplating your allegiances and your opponents. You see yourself as part of some groups and not others, and like those boys you spend a lot of time defining outsiders. The way you see others is deeply affected by something psychologists call the illusion of asymmetric insight, but to understand it let’s first consider how groups, like people, have identities – and like people, those identities aren’t exactly real.

Source: "The Breakfast Club," 1985, Universal

Hopefully by now you’ve had one of those late-night conversations fueled by exhaustion, elation, fear or drugs in which you and your friends finally admit you are all bullshitting each other. If you haven’t, go watch The Breakfast Club and come back. The idea is this: You put on a mask and uniform before leaving for work. You put on another set for school. You have costume for friends of different persuasions and one just for family. Who you are alone is not who you are with a lover or a friend. You quick-change like Superman in a phone booth when you bump into old friends from high school at the grocery store, or the ex in line for the movie. When you part, you quick-change back and tell the person you are with why you appeared so strange for a moment. They understand, after all, they are also in disguise. It’s not a new or novel concept, the idea of multiple identities for multiple occasions, but it’s also not something you talk about often. The idea is old enough that the word person derives from persona – a Latin word for the masks Greek actors sometimes wore so people in the back rows of a performance could see who was on stage. This concept – actors and performance, persona and masks – has been intertwined and adopted throughout history. Shakespeare said, “all the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” William James said a person “has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him.” Carl Jung was particularly fond of the concept of the persona saying it was “that which in reality one is not, but which oneself as well as others think one is.” It’s an old idea, but you and everyone else seems to stumble onto it anew in adolescence, forget about it for a while, and suddenly remember again from time to time when you feel like an impostor or a fraud. It’s ok, that’s a natural feeling, and if you don’t step back occasionally and feel funky about how you are wearing a socially constructed mask and uniform you are probably a psychopath.

Social media confounds the issue. You are a public relations masterpiece. Not only are you free to create alternate selves for forums, websites and digital watering holes, but from one social media service to the next you control the output of your persona. The clever tweets, the photos of your delectable triumphs with the oven and mixing bowl, the funny meme you send out into the firmament that you check back on for comments, the new thing you own, the new place you visited – they tell a story of who you want to be, who you ought to be. They satisfy something. Is anyone clicking on all these links? Is anyone smirking at this video? Are my responses being scoured for grammatical infractions? You ask these questions and others, even if they don’t rise to the surface.

Source: www.ravenwoodmasks.com

The recent fuss over the over-sharing, over the loss of privacy is just noisy ignorance. You know, as a citizen of the Internet, you obfuscate the truth of your character. You hide your fears and transgressions and vulnerable yearnings for meaning, for purpose, for connection. In a world where you can control everything presented to an audience both domestic or imaginary, what is laid bare depends on who you believe is on the other side of the screen. You fret over your father or your aunt asking to be your Facebook friend. What will they think of that version of you? In flesh or photons, it seems built-in, this desire to conceal some aspects of yourself in one group while exposing them in others. You can be vulnerable in many different ways but not all at once it seems.

So, you don social masks just like every human going back to the first campfires. You seem rather confident in them, in their ability to communicate and conceal that which you want on display and that which you wish was not. Groups too don these masks. Political parties establish platforms, companies give employees handbooks, countries write out constitutions, tree houses post club rules. Every human gathering and institution from the Gay Pride Parade to the KKK works to remain connected by developing a set a norms and values which signals to members when they are dealing with members of the in-group and help identify others as part of the out-group. The peculiar thing though is that once you feel this, once you feel included in a human institution or ideology, you can’t help but see outsiders through a warped lens called the illusion of asymmetric insight.

How well do you know your friends? Pick one out of the bunch, someone you interact with often. Do you see the little ways they lie to themselves and others? Do you secretly know what is holding them back, but also recognize the beautiful talents they don’t appreciate? Do you know what they want, what they are likely to do in most situations, what they will argue about and what they let slide? Do you notice when they are posturing and when they are vulnerable? Do you know the perfect gift? Do you wish they had never went out with so-and-so? Do you sometimes say with confidence, “You should have been there. You would have loved it,” about things you enjoyed for them, by proxy? Research shows you probably feel all these things and more. You see your friends, your family, your coworkers and peers as semipermeable beings. You label them with ease. You see them as the artist, the grouch, the slacker and the overachiever. “They did what? Oh, that’s no surprise.” You know who will watch the meteor shower with you and who will pass. You know who to ask about spark plugs and who to ask about planting a vegetable garden. You can, you believe, put yourself in their shoes and predict their behavior in just about any situation. You believe every person not you is an open book. Of course, the research shows they believe the same thing about you.

In 2001, Emily Pronin and Lee Ross at Stanford along with Justin Kruger at the University of Illinois and Kenneth Savitsky at Williams College conducted a series of experiments exploring why you see people this way.

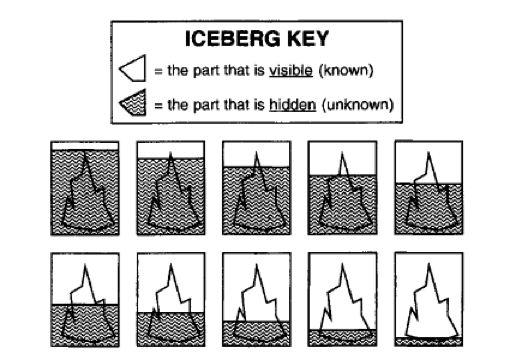

In the first experiment they had people fill out a questionnaire asking them to think of a best friend and rate how well they believed they knew him or her. They showed the subjects a series of photos showing an iceberg submerged in varying levels of water and asked them to circle the one which corresponded to how much of the “essential nature” they felt they could see of their friends. How much, they asked, of your friend’s true self is visible and much is hidden below the surface? They then had the subjects take a second questionnaire which turned the questions around asking them to put themselves in the minds of their friends. How much of their own iceberg did they think their friends could see? Most people rated their insight into their best friend as keen. They saw more of the iceberg floating above the water line. In the other direction they felt the insight their friend’s possessed of them was lacking, most of their own self was submerged.

In the first experiment they had people fill out a questionnaire asking them to think of a best friend and rate how well they believed they knew him or her. They showed the subjects a series of photos showing an iceberg submerged in varying levels of water and asked them to circle the one which corresponded to how much of the “essential nature” they felt they could see of their friends. How much, they asked, of your friend’s true self is visible and much is hidden below the surface? They then had the subjects take a second questionnaire which turned the questions around asking them to put themselves in the minds of their friends. How much of their own iceberg did they think their friends could see? Most people rated their insight into their best friend as keen. They saw more of the iceberg floating above the water line. In the other direction they felt the insight their friend’s possessed of them was lacking, most of their own self was submerged.

This and many other studies show you believe you see more of other people’s icebergs than they see of yours; meanwhile, they think the same thing about you.

The same researchers asked people to describe a time when they feel most like themselves. Most subjects, 78 percent, described something internal and unobservable like the feeling of seeing their child excel or the rush of applause after playing for an audience. When asked to describe when they believed friends or relatives were most illustrative of their personalities, they described internal feelings only 28 percent of the time. Instead, they tended to describe actions. Tom is most like Tom when he is telling a dirty joke. Jill is most like Jill when she is rock climbing. You can’t see internal states of others, so you generally don’t use those states to describe their personalities.

When they had subjects complete words with some letters missing (like g–l which could be goal, girl, gall, gill, etc.) and then ask how much the subjects believed those word completion tasks revealed about their true selves, most people said they revealed nothing at all. When the same people looked at other people’s word completions they said things like, “I get the feeling that whoever did this is pretty vain, but basically a nice guy.” They looked at the words and said the people who filled them in were nature lovers, or on their periods, or were positive thinkers or needed more sleep. When the words were their own, they meant nothing. When they were others’, they pulled back a curtain.

When Pronin, Ross, Kruger and Savitsky moved from individuals to groups, they found an even more troubling version of the illusion of asymmetric insight. They had subjects identify themselves as either liberals or conservatives and in a separate run of the experiment as either pro-abortion and anti-abortion. The groups filled out questionnaires about their own beliefs and how they interpreted the beliefs of their opposition. They then rated how much insight their opponents possessed. The results showed liberals believed they knew more about conservatives than conservatives knew about liberals. The conservatives believed they knew more about liberals than liberals knew about conservatives. Both groups thought they knew more about their opponents than their opponents knew about themselves. The same was true of the pro-abortion rights and anti-abortion groups.

The illusion of asymmetric insight makes it seem as though you know everyone else far better than they know you, and not only that, but you know them better than they know themselves. You believe the same thing about groups of which you are a member. As a whole, your group understands outsiders better than outsiders understand your group, and you understand the group better than its members know the group to which they belong.

The researchers explained this is how one eventually arrives at the illusion of naive realism, or believing your thoughts and perceptions are true, accurate and correct, therefore if someone sees things differently than you or disagrees with you in some way it is the result of a bias or an influence or a shortcoming. You feel like the other person must have been tainted in some way, otherwise they would see the world the way you do – the right way. The illusion of asymmetrical insight clouds your ability to see the people you disagree with as nuanced and complex. You tend to see your self and the groups you belong to in shades of gray, but others and their groups as solid and defined primary colors lacking nuance or complexity.

“Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself; (I am large, I contain multitudes.)”

-Walt Whitman from Song of Myself, Leaves of Grass

The two tribes of children in Oklahoma formed because groups are how human beings escaped the Serengeti and built pyramids and invented Laffy Taffy. All primates depend on groups to survive and thrive, and human groups thrive most of all. It is in your nature to form them. Sherif’s experiment with the boys at Robber’s Cave showed how quickly and easily you do so, how your innate drive to develop and observe norms and rituals will express itself even in a cultural vacuum, but there is a dark side to this behavior. As psychologist Jonathan Haidt says, our minds “unite us into teams, divide us against other teams, and blind us to the truth.” It’s that last part that keeps getting you into trouble. Just as you don a self, a persona, and believe it to be thicker and harder to see through than those of your friends, family and peers, you too believe the groups to which you belong are more complex, more diverse and granular than are groups of which you could never imagine yourself a member. When you feel the warm comfort of belonging to a team, a tribe, a group – to a party, an ideology, a religion or a nation – you instinctively turn others into members of outgroups, into outsiders. Just as soldiers come up with derogatory names for enemies, every culture and sub-culture has a collection of terms for outsiders so as to better see them as a single-minded collective. You are prone to forming and joining groups and then believing your groups are more diverse than outside groups.

In a political debate you feel like the other side just doesn’t get your point of view, and if they could only see things with your clarity, they would understand and fall naturally in line with what you believe. They must not understand, because if they did they wouldn’t think the things they think. By contrast, you believe you totally get their point of view and you reject it. You see it in all its detail and understand it for what it is – stupid. You don’t need to hear them elaborate. So, each side believes they understand the other side better than the other side understands both their opponents and themselves.

In a political debate you feel like the other side just doesn’t get your point of view, and if they could only see things with your clarity, they would understand and fall naturally in line with what you believe. They must not understand, because if they did they wouldn’t think the things they think. By contrast, you believe you totally get their point of view and you reject it. You see it in all its detail and understand it for what it is – stupid. You don’t need to hear them elaborate. So, each side believes they understand the other side better than the other side understands both their opponents and themselves.

The research suggests you and rest of humanity will continue to churn into groups, banding and disbanding, and the beautiful collective species-wide macromonoculture imagined by the most Utopian of dreams might just be impossible unless alien warships lay siege to our cities. In Sherif’s study, he was able to somewhat reintegrate the boys of the Robber’s Cave experiment by telling them the water supply had been sabotaged by vandals. The two groups were able to come together and repair it as one. Later he staged a problem with one of the camp trucks and was able to get the boys to work together to pull it with a rope until it started. They never fully joined into one group, but the hostilities eased enough for both groups to ride the same bus together back home. It seems peace is possible when we face shared problems, but for now we need to be in our tribes. It just feels right.

So, you pick a team, and like the boys at Robber’s Cave, you spend a lot of time a lot of time talking about how dumb and uncouth the other side is. You too can become preoccupied with defining the essence of your enemies. You too need the other side to be inferior, so you define them as such. You start to believe your persona is actually your identity, and the identity of your enemy is actually their persona. You see yourself in a game of self-deluded poker and assume you are impossible to read while everyone else has obvious tells.

The truth is, you are succumbing to the illusion of asymmetric insight, and as part of a flatter, more-connected, always-on world, you will be tasked with seeing through this illusion more and more often as you are presented with more opportunities than ever to confront and define those who you feel are not in your tribe. Your ancestors rarely made any contact with people of opposing views with anything other than the end of a weapon, so your natural instinct is to assume anyone not in your group is wrong just because they are not in your group. Remember, you are not so smart, and what seems like an insight is often an illusion.

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

If you buy one book this year…well, I suppose you should get something you’ve had your eye on for a while. But, if you buy two or more books this year, might I recommend one of them be a celebration of self delusion? Give the gift of humility (to yourself or someone else you love). Watch the trailer.

Order now: Amazon - Barnes and Noble - iTunes - Books A Million

Links:

Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass

The Illusion of Asymmetric Insight Study

July 6, 2011

Misattribution of Arousal

The Misconception: You always know why you feel the way you feel.

The Truth: You can experience emotional states without knowing why, even if you believe you can pinpoint the source.

Source: capbridge.com

The bridge is still in British Columbia, still long and scary, still sagging across the Capilano Canyon daring people to traverse it.

If you were to place the Statue of Liberty underneath the bridge, base and all, it would lightly drape across her copper shoulders. It is about as wide as a park bench for its entire suspended length, and when you try to cross, feeling it sway and rock in the wind, hearing it creak and buckle, it is difficult to take your eyes off of the rocks and roaring water two-hundred and thirty feet below – far enough for you feel in your stomach the distance between you and a messy, crumpled death. Not everyone makes it across.

In 1974, psychologists Art Aron and Donald Dutton hired a woman to stand in the middle of this suspension bridge. As men passed her on their way across, she asked them if they would be willing to fill out a questionnaire. At the end of the questions, she asked them to examine an illustration of a lady covering her face and then make up a back story to explain it. She then told each man she would be more than happy to discuss the study further if he wanted to call her that night, and tore off a portion of the paper, wrote down her number, and handed it over.

The scientists knew the fear in the men’s bellies would be impossible to ignore, and they wanted to know how a brain soaking in anxiety juices would make sense of what just happened. To do this, they needed another bridge to serve as a control, one which wouldn’t produce terror, so they had their assistant go through the same routine on a wide, sturdy, wooden bridge standing fixed just a few feet off of the ground.

After running the experiment at both locations, they compared the results and found 50 percent of the men who got them digits on the dangerous suspension bridge picked up a phone and called looking for the lady of the canyon. Of the men questioned on the secure bridge, the percentage who came calling dropped to 12.5. That wasn’t the only significant difference. When they compared the stories the subjects made up about the illustration, they found the men on the scary bridge were almost twice as likely to come up with sexually suggestive narratives.

What was going on here? One bridge made men flirty and eager to follow up with female interviewers, and one did not. To make sense of it, you must understand something psychologists call arousal and how easy it is to falsely identify its source. Mistaken emotional origins can save relationships, create amorous mirages and lead you into behaviors and attitudes both sublime and hypocritical.

Courtesy: Matthew Field

Arousal, in the psychological sense, is not limited to sexual situations. It can envelop you in a number of ways. You’ve felt it: increased heart rate, focused attention, sweaty palms, dry mouth, big breaths followed by bigger sighs. It is that wide-eyed, electricity in your veins feeling you get when the wind picks up and the rain begins to pour. It is a state of wakefulness, more alert and aware than normal, in which your mind is paying full attention to the moment. This isn’t the action-roll-out-of bed-feeling you get when a fire alarm snaps you out of a deep sleep. No, arousal is prolonged and total, it builds and saturates. Arousal comes from deep inside the brain, in those primal regions of the autonomic nervous system where ingoing and outgoing signals are monitored and the glass over the big fight-or-flight button waits to be smashed. You feel it as a soldier waiting to see if the next mortar has your name on it, as a musician walking on stage inside a sold-out stadium, as a crowd member elevated by a powerful speech, in a group circling a fire and singing and drumming, as a member of a congregation swimming in the Gospel and swaying with hands raised, in a couple at the center of a packed dance floor. Your eyes water with ease. You want to weep and laugh simultaneously. You could just explode.

The men on the bridge experienced this heightened state of clarity, fear, anxiety and dread, and when they met an attractive woman those feelings continued to flow into their hearts and heads, but the source got scrambled. Was it the bridge or the lady? Was she being nice, or was she interested? Why did she pick me? My heart is pounding – is she making me feel this way? When Aron and Dutton ran the bridge experiment with a male interviewer (and male subjects), the lopsided results disappeared. The men no longer considered the interviewer as a possible cause, or if they did they suppressed it. The misattribution of arousal also went away when they ran the experiment on a safe bridge. No heightened state, no need to explain it. On a hunch, Aron and Dutton decided to move the experiment away from the real world with all its uncontrollable variables and attack the puzzle from another direction in the lab.

In the lab experiment male college students entered a room full of scientific-looking electrical equipment where a researcher greeted them asking if they had seen another student wandering around. When the men said they hadn’t, the scientists pretended to go looking for the other subject and left behind reading material for the men to look over concerning learning and painful electric shocks. When the scientists felt like enough time had passed, they brought in an actress who pretended to be another student who had also volunteered for the study. The men, one at a time, would then sit beside the woman and listen as the scientists explained the subjects would soon be shocked with either a terrible, bowel-loosening megablast or a “mere tingle.” After all of this, the psychologists flipped a coin to determine who would be getting what. They weren’t actually going to shock anyone, they just wanted to scare the bejeezus out of the men. The researchers then handed over a questionnaire similar to the one from the bridge experiment, complete with the illustration interpretation portion, and told the men to work on it while they prepared the electrocution machines.

The questionnaire asked the men to rate their anxiety and their attraction to the other subject. As the scientists suspected, the results matched the bridge. The men who expected a terrible, painful future rated their anxiety and their attraction to the ladies as significantly higher than those expecting mild tingles. When it came to those narratives explaining the pictures, once again the more anxious the men, the more sexual imagery they produced.

Aron and Dutton showed when you feel aroused, you naturally look for context, an explanation as to why you feel so alive. This search for meaning happens automatically and unconsciously, and whatever answer you come up with is rarely questioned because you don’t realize you are asking. Like the men on the bridge, you sometimes make up a reason for why you feel the way you do, and then you believe your own narrative and move on. It is easy to pinpoint the source of your contorted face and toothy grin if you took peyote at Burning Man and are twirling glow sticks to the beat of a pulsating lizard-faced bassoon quartet. The source of your coursing blood is more ambiguous if you just drank a Red Bull before heading into a darkened theater to watch an action movie. You can’t know for sure it if it is the explosions or the caffeinated taurine water, but damn if this movie doesn’t rock. In many situations you either can’t know or fail to notice what got you physiologically amped, and you mistakenly attribute the source to something in your immediate environment. People, it seems, are your favorite explanations as studies show you prefer to see other human beings as the source of your heightened state of arousal when given the option. The men expecting to get electrocuted misattributed a portion of their pulse’s pace to the ladies by their sides. Aron and Dutton focused on fear and anxiety, but in the years since, research has revealed just about any emotional state can be misattributed, and this has led to important findings on how to keep a marriage together.

Source; www.shesknows.com

In 2008, psychologist James Graham at the University of North Carolina conducted a study to see what sort of activities kept partners bonded. He had 20 couples who lived together carry around digital devices while conducting their normal daily activities. Whenever the device went off, they had to use it to text back to the researchers and tell them what they were up to. They then answered a few questions about their mood and how they felt toward their partners. After over a thousand of these buzz-report-introspect-text moments, he looked over the data and found couples who routinely performed difficult tasks together as partners were also more likely to like each other. Over the course of his experiments, he found partners tended to feel closer, more attracted to and more in love with each other when their skills were routinely challenged. He reasoned the buzz you get when you break through a frustrating trial and succeed, what Graham called flow, was directly tied to bonding. Just spending time together is not enough, he said. The sort of activities you engage in are vital. Graham concluded you are driven to grow, to expand, to add to your abilities and knowledge. When you satisfy this motivation for self-expansion by incorporating aspects of your romantic partner or friend into your own skills, philosophies and self, it does more to strengthen your bond than any other act of love. This opens the door to one of the best things about misattribution of emotion. If, like those in the study, you persevere through a challenge – be it remodeling a kitchen yourself or learning how to Dougie – that glowing feeling of becoming more wise, that buoyant sense of self-expansion will be partially misattributed to the presence of the other person. You become conditioned over time to see the relationship itself as a source for those sorts of emotions, and you will become less likely to want to sever your bond with the other party. In the beginning, just learning how to relate to the other person and interpret their non-verbal cues, emotional swings and strange food aversions is an exercise in self-expansion. The frequency of novelty can diminish as the relationship ages and you settle into routines. The bond can seem to weaken. To build it up again you need adversity, even if simulated. Taking ballroom dancing lessons or teaming up against friends in Trivial Pursuit are more likely to keep the flame flickering than wine and Marvin Gaye.

I think falling in love occurs under the right circumstances and it is not a rational process, but it’s a predictable process.

- Psychologist Art Aron

The arousal you are prone to misattributing can also come from within, especially if you find yourself on questionable moral ground. Mark Zanna and Joel Cooper in 1978 gave placebo pills to a group of subjects. They told half of the pill takers the drug would make them feel relaxed, and they told the other half it would make them feel tense. They then asked the subjects to write an essay explaining why free speech should be banned. Most people were reluctant and felt terrible about expressing an opinion counter to their true beliefs. When the researchers gave all the participants a chance to go back and change their papers, the ones who thought they had taken a downer were far more likely to take them up on the offer. The ones who thought they took a speedy pill assumed the heat under their collars was from the drug instead of their own cognitive dissonance, so they didn’t feel the need to change their positions. The other group had no scapegoat for their emotional states, so they wanted to rewrite the paper because they suspected it would ease their minds and bring their arousal back down to normal. Cognitive dissonance, behaving in a way which seems to run counter to your beliefs, cranks up arousal in a way that feels awful. The subjects in the Zanna and Cooper experiment wanted to alleviate this, but only those who thought they took the downer could pinpoint the source of their mental discomfort. For the other group, the fake upper served as a red herring throwing them off the trail back to their own negative emotions.

Source: www.PsychNet.com

Misattribution of arousal falls under the self-perception theory. This theory goes back as far as William James, one of the founders of psychology. It posits your attitudes are shaped by observing your own behavior and trying to make sense of it. For instance, James would say if you saw a cricket on your arm and then flailed about rubbing your body up and down while screaming incoherently, you would later assume you had experienced fear and might then believe you were afraid of crickets. Self-perception theory says you look back on a situation like this as if in an audience trying to understand your own motivations. Sometimes, you jump to conclusions without all the facts. As with many theories, there is much research left to be done and plenty of debate, but in many ways James was right. You often do act as observer of your actions, a witness to your thoughts, and you form beliefs about your self based on those observations. Psychologist Fritz Strack devised a simple experiment in 1988 in which he had subjects hold a pen straight out between their incisors and bare their teeth as they read cartoon strips. The subjects tended to find the cartoons funnier than when they held the pen between their lips instead. Between the teeth, some of the muscles used for smiling were contracted, and between the lips they contracted some of the muscles used for frowning. He concluded the subjects felt themselves smiling and decided somewhere deep in their minds they must be enjoying the comics. When they felt themselves frowning, they assumed they thought the comics were dull. In a similar experiment in 1980 by Gary Wells and Richard Petty at the University of Alberta subjects were asked to test out headphones by either nodding or shaking their heads while listening to a pundit delivering an editorial. Sure enough, when questioned later the nodders tended to agree with the opinion of the speaker more than the shakers. In 2003, Jens Förster at International University Bremen asked volunteers to rate food items as they moved across a large screen. Sometimes the food names moved up and down, and sometimes side to side, thus producing unconscious nodding or head shaking. As in the pundit study, people tended to say they preferred the foods which made them nod unless they were gross. In Förster’s and other similar studies, positive and negative opinions became stronger, but if a person hated broccoli, for example, no amount of head nodding would change their mind.

Arousal can fill up the spaces in your brain when you least expect it. It could be a rousing movie trailer or a plea for mercy from a distant person reaching out over YouTube. Like a coterie of prairie dogs standing alert as if living periscopes, your ancestors were built to pay attention when it mattered, but with cognition comes pattern recognition and all the silly ways you misinterpret your inputs. The source of your emotional states is often difficult or impossible to detect. The time to pay attention can pass, or the details become lodged in a place underneath consciousness. In those instances you feel, but you know not why. When you find yourself in this situation you tend to lock onto a target, especially if there is another person who fits with the narrative you are about to spin. It feels good to assume you’ve discovered what is causing you to feel happy, to feel rejected, to feel angry or lovesick. It helps you move forward. Why question it?

Source: http://www.dailymail.co.uk

The research into arousal says you are bad at explaining yourself to yourself, but it sheds light on why so many successful dates include roller-coasters, horror films and conversations over coffee. If you want to get things rolling with a romantic interest you would be better served by bungee jumping or scuba diving, ice skating or rock climbing than candlelit dinners. No doubt, trapeze artists must have complicated and compelling love lives.

There is a reason playful wrestling can lead to passionate kissing, why a great friend can turn a heaving cry into a belly laugh. There is a reason why great struggle brings you closer to friends, family and lovers. There is a reason why Rice Krispies commercials show moms teaching children how to make treats in crisp black-and-white while Israel Kamakawiwo’ole sings Somewhere Over the Rainbow. When you want to know why you feel the way you do but are denied the correct answer, you don’t stop searching. You settle on something – the person beside you, the product in front of you, the drug in your brain. You don’t always know the right answer, but when you are flirting over a latte don’t point it out.

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

If you buy one book this year…well, I suppose you should get something you’ve had your eye on for a while. But, if you buy two or more books this year, might I recommend one of them be a celebration of self delusion? Give the gift of humility (to yourself or someone else you love). Watch the trailer.

Order now: Amazon - Barnes and Noble - iTunes - Books A Million

Links:

Video of Aron discussing bridge experiment

A followup to the pen in the mouth study

The food and head nodding study

The adversity and bonding study

The cognitive dissonance study

A meta-analysis of the Schachter theory of emotion

Where the body goes, the mind follows

Isreal Kamakawiwo’ole’s Somewhere Over the Rainbow

June 10, 2011

The Backfire Effect

The Misconception: When your beliefs are challenged with facts, you alter your opinions and incorporate the new information into your thinking.

The Truth: When your deepest convictions are challenged by contradictory evidence, your beliefs get stronger.

Wired, The New York Times, Backyard Poultry Magazine – they all do it. Sometimes, they screw up and get the facts wrong. In ink or in electrons, a reputable news source takes the time to say “my bad.”

Wired, The New York Times, Backyard Poultry Magazine – they all do it. Sometimes, they screw up and get the facts wrong. In ink or in electrons, a reputable news source takes the time to say “my bad.”

If you are in the news business and want to maintain your reputation for accuracy, you publish corrections. For most topics this works just fine, but what most news organizations don’t realize is a correction can further push readers away from the facts if the issue at hand is close to the heart. In fact, those pithy blurbs hidden on a deep page in every newspaper point to one of the most powerful forces shaping the way you think, feel and decide – a behavior keeping you from accepting the truth.

In 2006, Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler at The University of Michigan and Georgia State University created fake newspaper articles about polarizing political issues. The articles were written in a way which would confirm a widespread misconception about certain ideas in American politics. As soon as a person read a fake article, researchers then handed over a true article which corrected the first. For instance, one article suggested the United States found weapons of mass destruction in Iraq. The next said the U.S. never found them, which was the truth. Those opposed to the war or who had strong liberal leanings tended to disagree with the original article and accept the second. Those who supported the war and leaned more toward the conservative camp tended to agree with the first article and strongly disagree with the second. These reactions shouldn’t surprise you. What should give you pause though is how conservatives felt about the correction. After reading that there were no WMDs, they reported being even more certain than before there actually were WMDs and their original beliefs were correct.

They repeated the experiment with other wedge issues like stem cell research and tax reform, and once again, they found corrections tended to increase the strength of the participants’ misconceptions if those corrections contradicted their ideologies. People on opposing sides of the political spectrum read the same articles and then the same corrections, and when new evidence was interpreted as threatening to their beliefs, they doubled down. The corrections backfired.

They repeated the experiment with other wedge issues like stem cell research and tax reform, and once again, they found corrections tended to increase the strength of the participants’ misconceptions if those corrections contradicted their ideologies. People on opposing sides of the political spectrum read the same articles and then the same corrections, and when new evidence was interpreted as threatening to their beliefs, they doubled down. The corrections backfired.

Once something is added to your collection of beliefs, you protect it from harm. You do it instinctively and unconsciously when confronted with attitude-inconsistent information. Just as confirmation bias shields you when you actively seek information, the backfire effect defends you when the information seeks you, when it blindsides you. Coming or going, you stick to your beliefs instead of questioning them. When someone tries to correct you, tries to dilute your misconceptions, it backfires and strengthens them instead. Over time, the backfire effect helps make you less skeptical of those things which allow you to continue seeing your beliefs and attitudes as true and proper.

In 1976, when Ronald Reagan was running for president of the United States, he often told a story about a Chicago woman who was scamming the welfare system to earn her income.

Reagan said the woman had 80 names, 30 addresses and 12 Social Security cards which she used to get food stamps along with more than her share of money from Medicaid and other welfare entitlements. He said she drove a Cadillac, didn’t work and didn’t pay taxes. He talked about this woman, who he never named, in just about every small town he visited, and it tended to infuriate his audiences. The story solidified the term “Welfare Queen” in American political discourse and influenced not only the national conversation for the next 30 years, but public policy as well. It also wasn’t true.

Source: www.freerepublic.com

Sure, there have always been people who scam the government, but no one who fit Reagan’s description ever existed. The woman most historians believe Reagan’s anecdote was based on was a con artist with four aliases who moved from place to place wearing disguises, not some stay-at-home mom surrounded by mewling children.

Despite the debunking and the passage of time, the story is still alive. The imaginary lady who Scrooge McDives into a vault of foodstamps between naps while hardworking Americans struggle down the street still appears every day on the Internet. The memetic staying power of the narrative is impressive. Some version of it continues to turn up every week in stories and blog posts about entitlements even though the truth is a click away.

Psychologists call stories like these narrative scripts, stories that tell you what you want to hear, stories which confirm your beliefs and give you permission to continue feeling as you already do. If believing in welfare queens protects your ideology, you accept it and move on. You might find Reagan’s anecdote repugnant or risible, but you’ve accepted without question a similar anecdote about pharmaceutical companies blocking research, or unwarranted police searches, or the health benefits of chocolate. You’ve watched a documentary about the evils of…something you disliked, and you probably loved it. For every Michael Moore documentary passed around as the truth there is an anti-Michael Moore counter documentary with its own proponents trying to convince you their version of the truth is the better choice.

A great example of selective skepticism is the website literallyunbelievable.org. They collect Facebook comments of people who believe articles from the satire newspaper The Onion are real. Articles about Oprah offering a select few the chance to be buried with her in an ornate tomb, or the construction of a multi-billion dollar abortion supercenter, or NASCAR awarding money to drivers who make homophobic remarks are all commented on with the same sort of “yeah, that figures” outrage. As the psychologist Thomas Gilovich said, “”When examining evidence relevant to a given belief, people are inclined to see what they expect to see, and conclude what they expect to conclude…for desired conclusions, we ask ourselves, ‘Can I believe this?,’ but for unpalatable conclusions we ask, ‘Must I believe this?’”

This is why hardcore doubters who believe Barack Obama was not born in the United States will never be satisfied with any amount of evidence put forth suggesting otherwise. When the Obama administration released his long-form birth certificate in April of 2011, the reaction from birthers was as the backfire effect predicts. They scrutinized the timing, the appearance, the format – they gathered together online and mocked it. They became even more certain of their beliefs than before. The same has been and will forever be true for any conspiracy theory or fringe belief. Contradictory evidence strengthens the position of the believer. It is seen as part of the conspiracy, and missing evidence is dismissed as part of the coverup.

This helps explain how strange, ancient and kooky beliefs resist science, reason and reportage. It goes deeper though, because you don’t see yourself as a kook. You don’t think thunder is a deity going for a 7-10 split. You don’t need special underwear to shield your libido from the gaze of the moon. Your beliefs are rational, logical and fact-based, right?

Well…consider a topic like spanking. Is it right or wrong? Is it harmless or harmful? Is it lazy parenting or tough love? Science has an answer, but let’s get to that later. For now, savor your emotional reaction to the issue and realize you are willing to be swayed, willing to be edified on a great many things, but you keep a special set of topics separate.

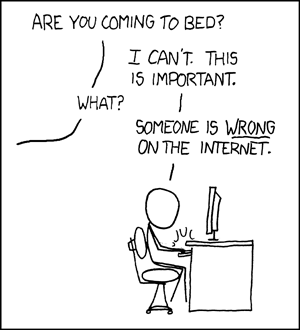

Source: www.xkcd.com

The last time you got into, or sat on the sidelines of, an argument online with someone who thought they knew all there was to know about health care reform, gun control, gay marriage, climate change, sex education, the drug war, Joss Whedon or whether or not 0.9999 repeated to infinity was equal to one – how did it go?

Did you teach the other party a valuable lesson? Did they thank you for edifying them on the intricacies of the issue after cursing their heretofore ignorance, doffing their virtual hat as they parted from the keyboard a better person?

No, probably not. Most online battles follow a similar pattern, each side launching attacks and pulling evidence from deep inside the web to back up their positions until, out of frustration, one party resorts to an all-out ad hominem nuclear strike. If you are lucky, the comment thread will get derailed in time for you to keep your dignity, or a neighboring commenter will help initiate a text-based dogpile on your opponent.

What should be evident from the studies on the backfire effect is you can never win an argument online. When you start to pull out facts and figures, hyperlinks and quotes, you are actually making the opponent feel as though they are even more sure of their position than before you started the debate. As they match your fervor, the same thing happens in your skull. The backfire effect pushes both of you deeper into your original beliefs.

Have you ever noticed the peculiar tendency you have to let praise pass through you, but feel crushed by criticism? A thousand positive remarks can slip by unnoticed, but one “you suck” can linger in your head for days. One hypothesis as to why this and the backfire effect happens is that you spend much more time considering information you disagree with than you do information you accept. Information which lines up with what you already believe passes through the mind like a vapor, but when you come across something which threatens your beliefs, something which conflicts with your preconceived notions of how the world works, you seize up and take notice. Some psychologists speculate there is an evolutionary explanation. Your ancestors paid more attention and spent more time thinking about negative stimuli than positive because bad things required a response. Those who failed to address negative stimuli failed to keep breathing.

In 1992, Peter Ditto and David Lopez conducted a study in which subjects dipped little strips of paper into cups filled with saliva. The paper wasn’t special, but the psychologists told half the subjects the strips would turn green if he or she had a terrible pancreatic disorder and told the other half it would turn green if they were free and clear. For both groups, they said the reaction would take about 20 seconds. The people who were told the strip would turn green if they were safe tended to wait much longer to see the results, far past the time they were told it would take. When it didn’t change colors, 52 percent retested themselves. The other group, the ones for whom a green strip would be very bad news, tended to wait the 20 seconds and move on. Only 18 percent retested.

When you read a negative comment, when someone shits on what you love, when your beliefs are challenged, you pore over the data, picking it apart, searching for weakness. The cognitive dissonance locks up the gears of your mind until you deal with it. In the process you form more neural connections, build new memories and put out effort – once you finally move on, your original convictions are stronger than ever.

When our bathroom scale delivers bad news, we hop off and then on again, just to make sure we didn’t misread the display or put too much pressure on one foot. When our scale delivers good news, we smile and head for the shower. By uncritically accepting evidence when it pleases us, and insisting on more when it doesn’t, we subtly tip the scales in our favor.

- Psychologist Dan Gilbert in The New York Times

The backfire effect is constantly shaping your beliefs and memory, keeping you consistently leaning one way or the other through a process psychologists call biased assimilation. Decades of research into a variety of cognitive biases shows you tend to see the world through thick, horn-rimmed glasses forged of belief and smudged with attitudes and ideologies. When scientists had people watch Bob Dole debate Bill Clinton in 1996, they found supporters before the debate tended to believe their preferred candidate won. In 2000, when psychologists studied Clinton lovers and haters throughout the Lewinsky scandal, they found Clinton lovers tended to see Lewinsky as an untrustworthy homewrecker and found it difficult to believe Clinton lied under oath. The haters, of course, felt quite the opposite. Flash forward to 2011, and you have Fox News and MSNBC battling for cable journalism territory, both promising a viewpoint which will never challenge the beliefs of a certain portion of the audience. Biased assimilation guaranteed.

Biased assimilation doesn’t only happen in the presence of current events. Michael Hulsizer of Webster University, Geoffrey Munro at Towson, Angela Fagerlin at the University of Michigan, and Stuart Taylor at Kent State conducted a study in 2004 in which they asked liberals and conservatives to opine on the 1970 shootings at Kent State where National Guard soldiers fired on Vietnam War demonstrators killing four and injuring nine.

As with any historical event, the details of what happened at Kent State began to blur within hours. In the years since, books and articles and documentaries and songs have plotted a dense map of causes and motivations, conclusions and suppositions with points of interest in every quadrant. In the weeks immediately after the shooting, psychologists surveyed the students at Kent State who witnessed the event and found that 6 percent of the liberals and 45 percent of the conservatives thought the National Guard was provoked. Twenty-five years later, they asked current students what they thought. In 1995, 62 percent of liberals said the soldiers committed murder, but only 37 percent of conservatives agreed. Five years later, they asked the students again and found conservatives were still more likely to believe the protesters overran the National Guard while liberals were more likely to see the soldiers as the aggressors. What is astonishing, is they found the beliefs were stronger the more the participants said they knew about the event. The bias for the National Guard or the protesters was stronger the more knowledgeable the subject. The people who only had a basic understanding experienced a weak backfire effect when considering the evidence. The backfire effect pushed those who had put more thought into the matter farther from the gray areas.

Geoffrey Munro at the University of California and Peter Ditto at Kent State University concocted a series of fake scientific studies in 1997. One set of studies said homosexuality was probably a mental illness. The other set suggested homosexuality was normal and natural. They then separated subjects into two groups; one group said they believed homosexuality was a mental illness and one did not. Each group then read the fake studies full of pretend facts and figures suggesting their worldview was wrong. On either side of the issue, after reading studies which did not support their beliefs, most people didn’t report an epiphany, a realization they’ve been wrong all these years. Instead, they said the issue was something science couldn’t understand. When asked about other topics later on, like spanking or astrology, these same people said they no longer trusted research to determine the truth. Rather than shed their belief and face facts, they rejected science altogether.

The human understanding when it has once adopted an opinion draws all things else to support and agree with it. And though there be a greater number and weight of instances to be found on the other side, yet these it either neglects and despises, or else-by some distinction sets aside and rejects, in order that by this great and pernicious predetermination the authority of its former conclusion may remain inviolate

- Francis Bacon

Science and fiction once imagined the future in which you now live. Books and films and graphic novels of yore featured cyberpunks surfing data streams and personal communicators joining a chorus of beeps and tones all around you. Short stories and late-night pocket-protected gabfests portended a time when the combined knowledge and artistic output of your entire species would be instantly available at your command, and billions of human lives would be connected and visible to all who wished to be seen.

So, here you are, in the future surrounded by computers which can deliver to you just about every fact humans know, the instructions for any task, the steps to any skill, the explanation for every single thing your species has figured out so far. This once imaginary place is now your daily life.

So, if the future we were promised is now here, why isn’t it the ultimate triumph of science and reason? Why don’t you live in a social and political technotopia, an empirical nirvana, an Asgard of analytical thought minus the jumpsuits and neon headbands where the truth is known to all?

Source: Irrational Studios/Looking Glass Studios

Among the many biases and delusions in between you and your microprocessor-rich, skinny-jeaned Arcadia is a great big psychological beast called the backfire effect. It’s always been there, meddling with the way you and your ancestors understood the world, but the Internet unchained its potential, elevated its expression, and you’ve been none the wiser for years.

As social media and advertising progresses, confirmation bias and the backfire effect will become more and more difficult to overcome. You will have more opportunities to pick and choose the kind of information which gets into your head along with the kinds of outlets you trust to give you that information. In addition, advertisers will continue to adapt, not only generating ads based on what they know about you, but creating advertising strategies on the fly based on what has and has not worked on you so far. The media of the future may be delivered based not only on your preferences, but on how you vote, where you grew up, your mood, the time of day or year – every element of you which can be quantified. In a world where everything comes to you on demand, your beliefs may never be challenged.

Three thousand spoilers per second rippled away from Twitter in the hours before Barack Obama walked up to his presidential lectern and told the world Osama bin Laden was dead.

Novelty Facebook pages, get-rich-quick websites and millions of emails, texts and instant messages related to the event preceded the official announcement on May 1, 2011. Stories went up, comments poured in, search engines burned white hot. Between 7:30 and 8:30 p.m. on the first day, Google searches for bin Laden saw a 1 million percent increase from the number the day before. Youtube videos of Toby Keith and Lee Greenwood started trending. Unprepared news sites sputtered and strained to deliver up page after page of updates to a ravenous public.

It was a dazzling display of how much the world of information exchange changed in the years since September of 2001 except in one predictable and probably immutable way. Within minutes of learning about Seal Team Six, the headshot tweeted around the world and the swift burial at sea, conspiracy theories began to bounce against the walls of our infinitely voluminous echo chamber. Days later, when the world learned they would be denied photographic proof, the conspiracy theories grew legs, left the ocean and evolved into self-sustaining undebunkable life forms.

As information technology progresses, the behaviors you are most likely to engage in when it comes to belief, dogma, politics and ideology seem to remain fixed. In a world blossoming with new knowledge, burgeoning with scientific insights into every element of the human experience, like most people, you still pick and choose what to accept even when it comes out of a lab and is based on 100 years of research.

So, how about spanking? After reading all of this, do you think you are ready to know what science has to say about the issue? Here’s the skinny - psychologists are still studying the matter, but the current thinking says spanking generates compliance in children under seven if done infrequently, in private and using only the hands. Now, here’s a slight correction: other methods of behavior modification like positive reinforcement, token economies, time out and so on are also quite effective and don’t require any violence.

Reading those words, you probably had a strong emotional response. Now that you know the truth, have your opinions changed?

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

If you buy one book this year…well, I suppose you should get something you’ve had your eye on for a while. But, if you buy two or more books this year, might I recommend one of them be a celebration of self delusion? Give the gift of humility (to yourself or someone else you love). Watch the trailer.

Order now: Amazon - Barnes and Noble - iTunes - Books A Million

Links:

The study on corrections and the backfire effect

The study on interpreting Kent State

Harvard Journalism school on narrative scripts

Obama’s birth certificate sways some, but not all skeptics

The study on biased assimilation

Dan Gilbert on motivated reasoning

When the Internet thinks it knows you

Paul Krugman on the Welfare Queen myth

A New York Times article on Reagan’s Welfare Queen story

A Welfare-Queen activism website

Osama Bin Laden conspiracy theories race around the world

0.9999 repeated to infinity is 1

David McRaney's Blog

- David McRaney's profile

- 582 followers