David McRaney's Blog, page 36

October 8, 2012

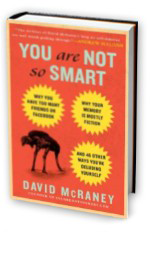

Book News – YANSS Now Available in the UK

The You Are Not So Smart book is now available in the UK and all the places that can get things shipped from Amazon.co.uk. Here is a link.

The video above is the launch trailer we used for the US edition, but the cover has been changed to match the absolutely spot-on UK version.

Also, the US edition will soon be available in paperback. I’ll post a tiny reminder when that happens. Look for versions in Brazil, Thailand, Korea, Germany, China, Hungary, Turkey, and Poland as well.

Finally, as I mentioned at the YANSS Facebook page, a second YANSS book is done and that’s all I can say about it right now other than it will probably find its way into bookstores sometime in 2013.

Thank you for being awesome. I will now post the latest episode of the podcast. Thanks so much for all the support. You are the best.

July 3, 2012

YANSS Podcast – Episode Four

The Topic: The Self

The Guest: Bruce Hood

The Episode: Download - iTunes - Stitcher - RSS - Soundcloud

Russian Dwarf Hamster – Photo by cdrussorusso

You are a pile of atoms.

When you eat vanilla pudding, which is also a pile of atoms, you are really just putting those atoms next to your atoms and waiting for some of them trade places.

If things had turned out differently back when your mom had that second glass of wine while your dad told that story about when he sat on a jellyfish while skinny dipping, the same atoms that glommed together to make your bones and your skin, your tongue and your brain could have been been rearranged to make other things. Carbon, oxygen, hydrogen – the whole collection of elements that make up your body right down to the vanadium, molybdenum and arsenic could be popped off of you, collected, and reused to make something else – if such a seemingly impossible technology existed.

Like a cosmic box of Legos, the building blocks of matter can take the shape of every form we know of from mountains to monkeys.

If you think about this long enough, you might stumble into the same odd questions scientists and philosophers ask from time to time. If we had an atom-exchanging machine, and traded one atom at a time from your body with an atom from the body of Edward James Olmos, at what point would you cease to be you and Olmos cease to be Edward James? During that process, would you lose your mind and gain his? At some point would each person’s thoughts and dreams and memories change hands?

The weird feeling produced by this thought experiment reveals something about the way you see yourself and others. You have an innate sense that there is something special within living things, especially people, and most especially yourself. Even if you are a hardcore materialist, you can’t prevent the little tug in your gut that makes you feel something might exist beyond the flesh, something not made of atoms. To you, living things seem to have an essence that is more than the sum of their parts. According to Bruce Hood, this is an illusion.

He created an experiment in which scientists introduced a hamster to a group of 6-year-olds. The researchers told the children that the hamster had a marble in its belly, a missing tooth, and a blue heart. They also showed the hamster a picture, tickled him, and whispered in his ear – these events, the children believed, would be remembered by the hamster. Everything the kids learned about the furball was an invisible trait. The difference was some things were physical aspects and other things were mental states.

He created an experiment in which scientists introduced a hamster to a group of 6-year-olds. The researchers told the children that the hamster had a marble in its belly, a missing tooth, and a blue heart. They also showed the hamster a picture, tickled him, and whispered in his ear – these events, the children believed, would be remembered by the hamster. Everything the kids learned about the furball was an invisible trait. The difference was some things were physical aspects and other things were mental states.

Next, they told the children that the scientists had invented a duplicating machine, and revealed two boxes. They then put the hamster in the first box, pretended to copy it, and opened both boxes revealing two identical hamsters. Unbeknownst to the kids, the second box already contained a twin. They asked the dazzled tikes if the copied hamster had all of the same qualities as the original. About a third said it had all, and a third said it had none, but the remaining third said that only the physical properties had been copied. The memories, they assumed, were impossible to duplicate. When they repeated the experiment with digital cameras, telling the kids the cameras had photos inside in addition to blue batteries. The kids saw no problems. The majority assumed everything in the camera could be copied, including the photos.

Hood’s experiment produced evidence to support the notion that at a certain age you begin to see minds and bodies as different things. As you grow up, you grow into believing in selves, in identities that are intangible and can’t be exchanged or copied at the atomic level. The problem, says Hood and other materialists, is that the self is generated by the mind, and the mind is generated by the brain, and the brain is just a sack of atoms, and atoms can be exchanged and rearranged, and maybe, one day, copied.

In this episode of the podcast, Bruce Hood talks about his book The Self Illusion and how ideas of materialism and dualism are being explored by modern science. Hood is a superstar of psychology and the Director of the Bristol Cognitive Development Centre in the Experimental Psychology Department at the University of Bristol. I love this interview, especially the part where he talks about consciousness within an artificial intelligence.

After the interview, as in every episode, I read a bit of self delusion news and taste a cookie baked from a recipe sent in by a listener/reader. That listener/reader wins a signed copy of the YANSS book, and I post the recipe on the YANSS Pinterest page. This episode’s winners are Andrea Niosi and Michael Burke who submitted a recipe for Crispy and Chewy Chocolate Oatmeal Cookies. You can see the recipe at their website here. Send your recipes to david {at} youarenotsosmart.com.

LINKS:

Download - iTunes - Stitcher - RSS - Soundcloud

Bruce Hood discusses essentialism

May 30, 2012

YANSS Podcast – Episode Three

The Topic: Confabulation

The Guest: V.S. Ramachandran

The Episode: iTunes – Download – Stitcher – RSS - Soundcloud

Caden Cotard in Synecdoche, New York. Source: Sony Pictures Classics

As a motto for the sapient, “cogito ergo sum” is pretty fantastic. Every time I’m reminded of it, a twinge of pride flows through my veins. It makes me want to stand up straight and pronounce proudly to my cat, “I think, therefore I am,” and then take his blank stare and plaintive meow as confirmation of my vitality. To be human is to know you exist. It is to know you are, and to know you are you.

It’s fitting that Jules Cotard, a man who was a close friend of the philosopher Auguste Comte, would find a way to dull the edge of Descartes’ famous proclamation. In an era preceding automobiles and airplanes, Cotard transferred his interest in the philosophy of being into the medicine of being – neurology – and after serving as a military surgeon in 1870, Cotard joined a clinic that did what it could with the knowledge of the day. Cotard and others at the clinic treated those with what one lecturer at the time called “madness in all its forms.”

Cotard was one of the pioneers of neuroscience, connecting behavior to the physical locations in the brain. As he progressed in his career he became particularly interested in patients who exhibited aphasia, or difficulties with language. He would follow those patients past death to the autopsy table in search of the cause of their maladies, and he encouraged other doctors to do the same. Considering his background in philosophy, it must have been astonishing when he found a patient devoid of a sense of self. In 1880, Cotard introduced a newly identified medical condition to the world. He called it “delire des negations,” or negation delirium. Essentially, he had discovered a condition in which a person thought, “I think, therefore I’m not.”

He told an audience in Paris that sometimes when a person’s brain was injured in the just the right way that person could become convinced he or she was dead. No amount of reason, no amount of cajolative acrobatics could talk a person out of the fantasy. In addition, the condition wasn’t purely psychological. It originated from a physiological problem in the brain. That is, this is a state of mind you too could suffer should you receive a strong enough blow to the head.

There are about 100 accounts in the medical literature of people displaying what is now known as Cotard’s delusion. It is also sometimes known, unsettlingly, as walking corpse syndrome. If you were to develop Cotard’s delusion you might look in the mirror and find your reflection suspicious, or you may cease to feel as through the heartbeat in your chest is yours, or you may think parts of your body are rotting away. In the most extreme cases, you may think you’ve become a ghost and decide you no longer need food. One of Cotard’s patients died of starvation.

Cotard’s syndrome and its delusions are part of a family of symptoms found in other disorders that all share the same central theme – the loss of your ability to emotionally connect with others. It is possible for something to go very wrong inside your skull so that your brain can no longer feel a difference between a stranger and a lover. The emotional flutter of recognition no longer comes, not for your dog, your mother, or your own voice. If you were to see a loved one and not feel the love, you would scramble to make sense of the situation. Sans emotion, those things become impostors or robots or dopplegangers. If the connection is severed to your own image, it becomes reasonable to assume you are an illusion. Faced with such a horrifying perception, you will invent a way to deal with it.

What this reveals is your remarkable penchant for making shit up. For all of existence, there is an internal narrative upon which you cling, a story you construct minute-by-minute to assure yourself that you understand what is happening. Sufferers of conditions like Cotard’s delusion invent weird, nonsensical explanations for their reality because they are experiencing weird, nonsensical input. The only difference between these patients’ explanations and your own explanations is the degree to which they are obviously, verifiably false. Whatever explanations you manufacture at any given moment to explain your state of mind and body could be similarly muddled, but you don’t have fact checkers constantly doting over your mental health. Whether or not your brain is damaged, your mind is always trying to explain itself to itself, and the degree of accuracy varies moment to moment.

What this reveals is your remarkable penchant for making shit up. For all of existence, there is an internal narrative upon which you cling, a story you construct minute-by-minute to assure yourself that you understand what is happening. Sufferers of conditions like Cotard’s delusion invent weird, nonsensical explanations for their reality because they are experiencing weird, nonsensical input. The only difference between these patients’ explanations and your own explanations is the degree to which they are obviously, verifiably false. Whatever explanations you manufacture at any given moment to explain your state of mind and body could be similarly muddled, but you don’t have fact checkers constantly doting over your mental health. Whether or not your brain is damaged, your mind is always trying to explain itself to itself, and the degree of accuracy varies moment to moment.

We call these false accounts confabulations – unintentional lies. Confabulations aren’t true, but the person making the claims doesn’t realize it. Neuroscience now knows that confabulations are common and continuous in the both the healthy and the afflicted, but in the case of Cotard’s delusion they are magnified to grotesque proportions.

One of the leading neuroscientists in our era, maybe the leading neuroscientist, is V.S. Ramachandran, and he is the guest in this episode of the You Are Not So Smart Podcast. I’ve included a transcript in the links, since the interview took place in a noisy room. It’s also in the lyrics section of the iTunes track. Ramachandran has written extensively about phantom limbs and paralysis as well as the confabulations often conjured by those who experience such problems. His research includes everything from mirror neurons to synesthesia, and you can find dozens of his fascinating lectures online. He is the director of the University of San Diego’s Center for Brain and Cognition, and he is the author of The Tell-Tale Brain and co-author of Phantoms in the Brain.

After the interview, as in every episode, I taste a cookie baked from a recipe sent in by a listener/reader. That listener/reader wins a signed copy of the book, and I post the recipe on the YANSS Pinterest page. This week’s winner is Stef Marcinkowski of Ontario, Canada. Her recipe for kickass cranberry chocolate cookies included a piece of art based on the last episode. This is her website. You can see the image and the cookies below.

Links/Sources:

The Podcast: iTunes – Download – Stitcher – RSS - Soundcloud

Center for Brain and Cognition

The study mentioned in the episode about self affirmation

The paper from which I learned about Cotard’s life

May 9, 2012

YANSS Podcast – Episode Two

The Topic: The Illusion of Knowledge

The Guest: Christopher Chabris

The Episode: iTunes – Download – Stitcher – RSS

Remember when the United States stock market crashed a few years back? You know, the implosion famously featuring credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations? Does it seem strange to you that all those experts who couldn’t predict the economic collapse are still on television giving advice and offering predictions?

The people who were wrong continue to work because they provide you with an illusion of knowledge, a belief that the market can be understood by one person, and that person’s understanding can become your understanding. They continue to claim insight into chaotic, impossibly complex nebulae of shifting data, and they continue to profess powers of divination even though research shows they are slightly less reliable than a coin toss. They can still get paid to squawk because they continue to make their claims with confidence. No one wants a sage who deals in maybes.

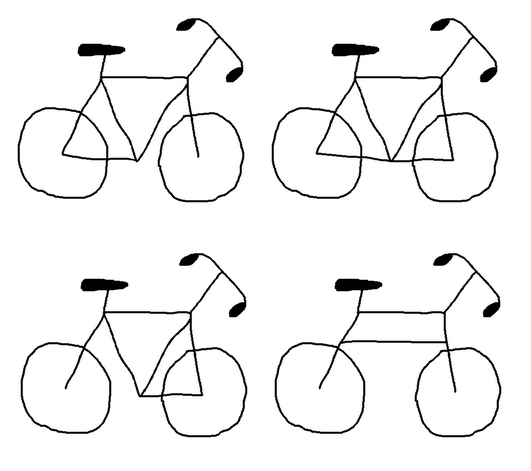

Take a look at those bicycles at the top of this post. Which one would you say is the most accurate portrayal of a real bike? Psychologist Rebecca Lawson once put together a study that revealed even though most people are very familiar with bicycles and know how to ride them, they can’t draw one to save their lives, and they can’t even pick a proper one out of a lineup. Despite this, most people rate their knowledge of how a bicycle works as being very good. Remember that when someone claims to understand something a bit more complicated, like a sub-prime mortgage. (This is a picture of a real bicycle.)

The illusion of knowledge is believing familiarity is the same as wisdom. You’ve probably felt it when trying to do something like fix a sink or explain to a child how taco shells are made. Just because you’ve become familiar with the operation and function of a thing doesn’t mean you truly understand how it works. For most of life, your understanding is only of the surface, the visible aspects that allow for a reasonable level of prediction. If you were teleported back to medieval times and placed outside a castle, what understanding could you offer those people from your own time?

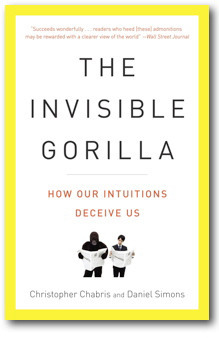

This episode of the You Are Not So Smart Podcast is all about the illusion of knowledge, something this episode’s guest, Union College psychologist Christopher Chabris, wrote about extensively in The Invisible Gorilla which he co-authored with psychologist Daniel Simons. Their book not only covers the many ways you miss what is going on around you, but it also discusses how overly confident you become when reflecting on your own memories, perceptions, and understanding. The bit about Lawson’s bicycles is in there, and much more.

Each episode of the podcast features a cookie tasting while I read and explain a bit of psychology or self-delusion news. The cookies come from the recipes you send in, and if I (or my wife) bake your recipe you receive a signed copy of the YANSS book. (Send those recipes to david [at] youarenotsosmart.com) This week’s winner is Gigi Greene who originally posted her recipe for her famous triple-ginger molasses cookies at her blog. You can find the recipe for this and all future cookies sent my way at the YANSS cookie recipe Pinterest page.

Oh, and everyone keeps asking about the theme music. The opening is by Caravan Palace, and the song is Clash. The beds are by www.blackguardsmg.com.

April 28, 2012

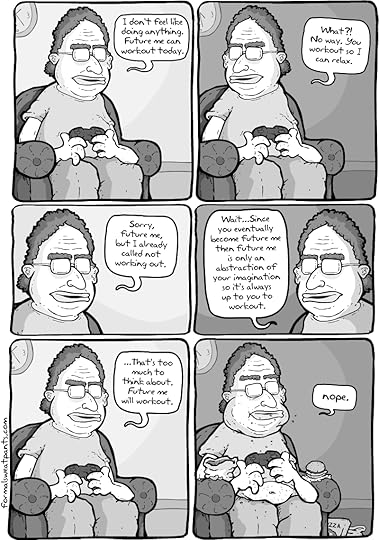

Formal Sweatpants Procrastination Comic

Josh Mecouch over at Formal Sweatpants created a new comic based on a YANSS post a while back on procrastination. Thanks, Josh. This is great. That post discussed the concept of future self vs. present self, and how present bias affects your ability to predict how you will behave and make choices over time.

You may see some future collaborations between YANSS and FS, stay tuned. Until then, here is the comic:

Links:

April 24, 2012

YANSS Podcast – Episode One

The Topic: Attention

The Guest: Daniel Simons

The Episode: iTunes – Download - RSS

The video above demonstrates the Monkey Business Illusion. It’s designed to fool both people who have and have not seen the selective attention test, a video on YouTube with over 5 million views.

The first post at You Are Not So Smart was about inattentional blindness. I had seen the selective attention test and the Test Your Awareness videos that were making the rounds on YouTube, and I knew inattentional blindness would make a great first topic. It is astounding to realize you’ve been lying to yourself about what gets into your brain through your eyeballs.

What is inattentional blindness? It’s missing something right in front of your eyes because you are paying attention to something else. What makes that a great topic for You Are Not So Smart is that this blindness is always part of experience, but you can spend a lifetime without ever knowing it happens. You tend to have an intuition and a belief that you see everything you are facing, and if something out of the ordinary was to happen, it would instantly grab your attention. Not so. Science has revealed you are basically blind to that which you are not attentive, yet your conscious experience and your memories don’t reflect this. That’s the epiphany that slams into your brain when you watch the original invisible gorilla video.

So, when I decided experiment with a You Are Not So Smart podcast, I knew I wanted to interview the scientists behind the invisible gorilla video, study, and book.

So, when I decided experiment with a You Are Not So Smart podcast, I knew I wanted to interview the scientists behind the invisible gorilla video, study, and book.

Their book covers the many ways you miss what is going on around you thanks to your imperfect senses, and it also breaks down your unrealistic confidence in both those senses and the memories they form.

The book is co-written by two psychologists, so I broke the interviews into two episodes. In episode one, I interview Daniel Simons. He is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Illinois.

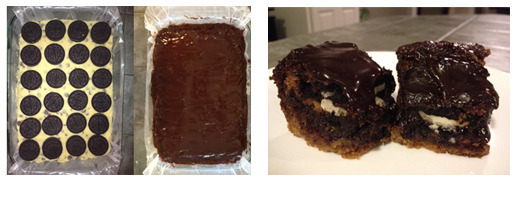

Also, as promised, each episode will feature a cookie tasting while I read and explain a bit of psychology or self-delusion news. The cookies come from the recipes you send in, and if I (or my wife) bake your recipe you receive a signed copy of the YANSS book. (Send those to david [at] youarenotsosmart.com) This week’s winner is Joe Frayer of Indianapolis. He sent in a recipe for chocolate-chip cookie and Oreo fudge brownie bars. His sister made them first and posted about them on her blog. She found the original recipe on this site. You can find the recipe for this and all future cookies recipes sent my way at the YANSS cookie recipe Pinterest page.

Photo of our first baking:

Links:

YANSS Cookie Recipe Pinterest Page

The Cocktail Party Effect Identified in the Brain

April 17, 2012

Ego Depletion

The Misconception: Willpower is just a metaphor.

The Truth: Willpower is a finite resource.

Forever Alone by Lysgaard

(Source: Lysgaard)

In 2005, a team of psychologists made a group of college students feel like scum.

The researchers invited the undergraduates into their lab and asked the students to just hang out for a while and get to know each other. The setting was designed to simulate a casual meet-and-greet atmosphere, you know, like a reception or an office Christmas party – the sort of thing that never really feels all that casual?

The students divided into same-sex clusters of about six people each and chatted for 20 minutes using conversation starters provided by the researchers. They asked things like “Where are you from?” and “What is your major?” and “If you could travel anywhere in the world, where would you go?” Researchers asked the students beforehand to make an effort to learn each other’s names during the hang-out period, which was important, because the next task was to move into a room, sit alone, and write down the names of two people from the fake party with whom the subjects would most like to be partnered for the next part of the study. The researchers noted the responses and asked the students to wait to be called. Unbeknownst to the subjects, their choices were tossed aside while they waited.

The researchers – Roy F. Baumeister, C. Nathan DeWall, Natalie J. Ciarocco and Jean M. Twenge of Florida State, Florida Atlantic, and San Diego State universities – then asked the young men and women to proceed to the next stage of the activity in which the subjects would learn, based on their social skills at the party, what sort of impression they had made on their new acquaintances. This is where it got funky.

The scientists individually told the members of one group of randomly selected people, “everyone chose you as someone they’d like to work with.” To keep each person in the wanted group isolated, the researchers also told each person the groups were already too big and he or she would have to work alone. Students in the wanted group proceeded to the next task with a spring in their step, their hearts filled with moonbeams and fireworks. The scientists individually told each member of another group of randomly selected people, “I hate to tell you this, but no one chose you as someone they wanted to work with.” Believing absolutely no one wanted to hang out with them, people in this group then learned they would have to work by themselves. Punched in the soul, their self-esteem dripping with inky sludge, the people in the unwanted group proceeded to the main task.

The task, the whole point of going through all of this as far as the students knew, was to sit in front of a bowl containing 35 mini chocolate-chip cookies and judge those cookies on taste, smell, and texture. The subjects learned they could eat as many as they wanted while filling out a form commonly used in corporate taste tests. The researchers left them alone with the cookies for 10 minutes.

This was the actual experiment – measuring cookie consumption based on social acceptance. How many cookies would the wanted people eat, and how would their behavior differ from the unwanted? Well, if you’ve had much contact with human beings, and especially if you’ve ever felt the icy embrace of being left-out of the party or getting picked last in kickball, your hypothesis is probably the same as the one put forth by the psychologists. They predicted the rejects would gorge themselves, and so they did. On average the rejects ate twice as many cookies as the popular people. To an outside observer, nothing was different – same setting, same work, similar students sitting alone in front of scrumptious cookies. In their heads though, they were on different planets. For those on the sunny planet with the double-rainbow sky, the cookies were easy to resist. Those on the rocky, lifeless world where the forgotten go to fade away found it more difficult to stay their hands when their desire to reach into the bowl surfaced.

Why did the rejected group feel motivated to keep mushing cookies into their sad faces? Why is it, as explained by the scientists in this study, that social exclusion impairs self-regulation? The answer has to do with something psychologists now call ego depletion, and you would be surprised to learn how many things can cause it, how often you feel it, and how much in life depends on it. Before we get into all of that, let’s briefly discuss the ego.

Freud in 1885

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

So, there was this guy named Sigismund Schlomo Freud. He was born in 1856, the oldest of eight children. He grew up and became a doctor. He loved cocaine and cigars. He escaped the Nazis but lost his sisters to concentration camps, and in 1939, an old man in great pain from mouth cancer, he used assisted suicide to shuffle off his mortal coil. Time Magazine once named him one of the most important thinkers of the 20th century. He is why the word “ego” is part of everyday language, and he is probably the first face you imagine when someone says “psychology.”

Despite his fame, the late 1800s wasn’t a good time to be in need of mental or physical care. Medical school was mostly about anatomy, physiology and the classics. You drew the insides of things and wondered what they did. You learned where the heart was, how to amputate a leg, and what Plato had to say about his cave. Pretty much everything useful that doctors know today was yet to be discovered or understood. Sore throat? No problem. Tie some peppered bacon around your neck. Hernia? Lie down so you can anally absorb a little tobacco smoke. The wild west of science and medicine was only just becoming tamed, so in many places there was still debate over things like washing your hands after dealing with a fetid corpse before sticking them still sticky into the body of a woman giving birth.

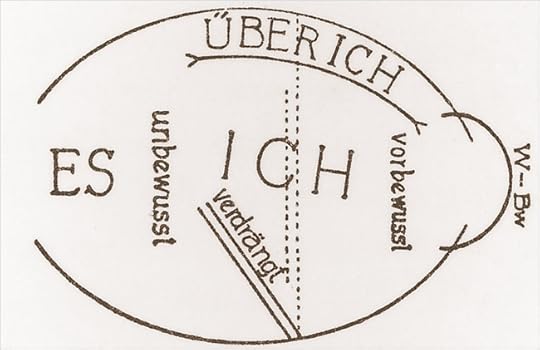

Near the end of his studies, Freud set himself to the squishy, messy task of slicing apart eels. He dissected 400 of them looking for testicles, a feature of the animal still unknown to science at the time. It was thoroughly disgusting and unfulfilling work, and it went nowhere. If he had found testes, his name might appear in different textbooks today. Instead, he earned his medical degree and went to work in a hospital where he spent years studying the brain, drawing neurons, and searching in that gelatinous goop much as he had the innards of the eels. But, as it does for so many of us, money became a central concern, and to pay the bills he abandoned the laboratory to set up his own medical practice. He remained the same intense, obsessive Freud though, and as he searched for the source of nervous disorders by going farther and farther back into the childhoods and histories of his patients he began to sketch out the geography and anatomy of the mind. This is how he came to produce his model of the psyche. Freud imagined behavior and thought, neurosis and malady, were all the result of an interplay and communication between mental agencies each with their own functions. He called those agencies “das Es,” “das Ich,” and “das Über-Ich” or “the it,” “the I,” and the “over-I,” – what would famously become known to English speakers as the id, the ego and the superego. In Freud’s view, the id was the primal part of the mind residing in the unconscious, always seeking pleasure while avoiding uncomfortable situations. The ego was the realistic part of the mind that considered the consequences of punching people in the face or stealing their french fries. When the ego lost a battle with the id over control of the mind, the super-ego would tower over the whole system and shake its metaphorical head in disgust. This, Freud thought, forced the ego to take control or hide behind denial or rationalization or any one of many defense mechanisms so as to avoid the harsh judgment of the super-ego from which morals and cultural norms exerted their influence. Of course, none of this is actually true. It was just the speculation of a well-educated man at about the same time penicillin was discovered.

Freud's Model of the Psyche

(Source: UNH)

Doctors like Freud could hypothesize whatever they wished, and if they were charismatic enough in person and on paper, they would lead the conversation in science. Once, Freud treated a female patient who complained of menstrual cramps. He sent her to an ear, nose, and throat doctor he knew who had this hypothesis that runny noses and menstruation were connected. During recovery, after her nasal cavity had received a proper chiseling, she complained of a growing pain in her sinuses that not even morphine could abate, and one night she produced two bowls of pus before horking out a piece of bone the size of a water chestnut. Freud concluded the hemorrhage was the result of a hysterical episode fueled by repressed sexual longings. A return trip to the surgeon determined it was actually a leftover piece of gauze. Freud remained unconvinced, claiming her relief came from psychoanalysis.

The point here is that science has come a long way since then, and although Freud’s work is still a big part of pop culture and everyday language – Freudian slips, repression, anal retentiveness, etc. – it’s mostly bunk, and you know this because psychology became a proper science over the last century with rigorous lab work published in peer reviewed journals. Today, scientists are still slicing away at the problem of consciousness and the ego, or what we now call the self, and that brings us back to Roy F. Baumeister and his bowl of cookies.

In the 1990s, Baumeister and his colleagues spent a lot of time researching self-regulation through the careful application of chocolate. Self-regulation is an important part of being a person. You are the central character in the story of your life, the unreliable narrator in the epic tale of your past, present, and future. You have a sense there is boundary between you and all the other atoms pulsating nearby, a sense of being a separate entity and not just a bag of organs and cells and molecules scooped out of the sea 530 million years ago. That sense of self cascades into a variety of other notions about your body and your mind called volition – the feeling of free will that provides you with the belief that you are in control of your decisions and choices. Volition makes you feel responsible for your actions both before and after they occur. There are a few thousand years of debate over what this actually means and whether or not it is an illusion through and through, but Baumeister’s research over the last decade or so has been about learning how that sense of self-control can be manipulated.

In 1998, Baumeister and his colleagues Ellen Bratlavsky, Mark Muraven, and Dianne M. Tice at Case Western Reserve University gathered subjects for a study. They told the participants the research was on taste perception, and thus each person was to skip a meal before the experiment and arrive with an empty stomach. The scientists led the subjects one at a time into a room with an oven that had just finished baking chocolate-chip cookies and had each person sit down in front of a selection of two foods – chocolate-chip cookies stacked high and a lone bowl of radishes. They asked a third of the participants to eat only the radishes and to take note of the sensations for follow up questions the next day. Another third were to eat only the cookies. A final third skipped all of this. The psychologists then left the room for five minutes and returned with a questionnaire about mood. According to Baumeister’s book on his research, Willpower, written with the help of John Tierney, the typical radish eater stared the cookies down like a gunfighter on main street. Some even went so far as to grab the cookies and put them to their noses. If they couldn’t have the taste, they could at least take a long, deep drag on the aroma. Still, the radish group stuck to the rules, not one of them ate a cookie, but not without some anguish. Next, the subjects moved on to a second experiment along with the group that skipped the food completely. The next task was to sit and solve puzzles. All each subject had to do was trace a geometric figure without lifting his or her pencil or retracing any lines. They were told they could take as long as they wanted, but they weren’t told that the puzzles were impossible to solve. For the next 30 minutes, the scientists watched and recorded the behavior of the participants, eager to see how long it would take each one to give up.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

On average, the people left out of the room with the radishes and the cookies worked for about 20 minutes before admitting defeat. The people allowed cookies persevered for about 19 minutes. The people who got stuck with the radishes, and had to fight off their impulse to gobble up a delicious confection in a room saturated with chocolate fumes, quit after approximately 8 minutes. Baumeister said of this, “Resisting temptation seems to have produced a psychic cost.” Somehow, the evidence suggested the more you restrain that which Freud would have called your id, the more difficult it becomes to restrain it. Freud would have probably have said the more your ego fought the id, the more it held it down, the more tired, exhausted, and weak your ego became. Baumeister named this process ego depletion with a nod and wink.

Baumeister and his colleagues soon discovered many other ways to get people to give up early. In one study, college students divided into three groups. One group had to give a speech supporting raising tuition at their college. A second group chose between a speech for or against tuition hikes. A third group proceeded directly to the second stage – those devious, unsolvable puzzles. This time, the no-speech group and the group that gave the speech with which they likely disagreed both lasted about twice as long as the people who got to choose what they spoke about. The results suggested it wasn’t just restraint in the face of desire that could deplete your ego, but any choice at all. The subjects who didn’t have to choose a topic were able to allow their volition to take a break, and their ego energy reserves remained intact. Another study had participants attempt to show and feel no emotion while watching video of either stand-up comedy or an actor pretending to die from cancer. They then tried to solve word puzzles along with people who watched the same videos with the freedom to feel whatever they wished. This time, the people who exerted emotional restraint subsequently solved fewer puzzles than those who let their feelings flow.

In a study about active and passive choices, subjects had to find all instances of the letter e on a piece of paper filled with nonsense text. Another group had to find every e that was at least two letters distant from a vowel. Try it yourself in this paragraph and you’ll notice the first group’s task was way easier and required little effort. The e finders who had to adhere to the vowel rule took much longer as they had to examine every word and double-check themselves. Next, people in each group individually watched a video of a blank wall while holding a remote control. For some people pressing a button would end the video. For others pressing down kept the video running. The subjects then had to watch the boring video until they believed they had seen enough to answer a questionnaire about it. Nothing ever happened in the video, but something might have happened at any moment as far as the subjects knew. Each person was also told as soon as he or she ended the video they would get to watch a clip from Saturday Night Live. The people who first performed the easy task and then had to press a button to end the boring video did so much sooner than the depleted group. They also held the button down longer when letting it go meant ending the clip. The depleted group just went with whatever was the most passive option in either case. If it was to press a button, they procrastinated. If it was to hold a button down, they gave up sooner. The results suggested that focused concentration later made people less eager to make active choices.

A great deal of your thoughts and behaviors are automatic and unconscious. Blinking and breathing, for example, need no help from the conscious part of you. Much of your behavior, like driving to work or toweling off after a shower, just happens while your conscious mind drifts off to think about Game of Thrones or how you’ll approach your boss for a raise. If you touch a stove you recoil without thought. Your desire to avoid dark alleys and approach embraces occurs without your input. When moved by a song or a painting or a kitten, the emotional rush comes without volition. Much of your mental life is simply not under your conscious control, and Baumeister’s research suggests once you take the helm every act of volition diminishes the next.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

It is as if the mind is a terribly designed airplane. As long as the plane flies in a straight line, it burns very little fuel, but as soon as the pilot takes over in any way, to dive or bank or climb, the plane burns fuel at an alarming rate making it more difficult to steer in the future. At some point, you must return the plane to autopilot until it can refuel or else it crashes. In this analogy, taking control of the human mind includes making choices, avoiding temptation, suppressing emotions and thoughts, and acting in a way deemed appropriate by your culture. Saying no to every naughty impulse from raiding the refrigerator to skipping class requires a little bit of willpower fuel, and once you spend that fuel it becomes harder to say no the next time. All of Baumeister’s research suggests self-control is a strenuous act. As your ego depletes, your automatic processes get louder, and each successive attempt to take control of your impulses is less successful than the last. Yet, ego depletion is not just the effects of fatigue. Being sleepy, drunk, or in the middle of a meth binge will certainly diminish your ability to resist pie, but what makes ego depletion so weird is that the research suggests the system affected by lack of sleep and excess of drink can get worn out just from regular use. Inhibiting and redirecting your own behavior in any way makes it more difficult to delay gratification and persevere in the face of adversity or boredom in the future.

So, why is it then that the students hit by the rejection bus, the ones told that no one picked them after listening to them prattle at the fake party, couldn’t keep the cookies out of their mouths? It seems as though ego depletion can go both ways. Getting along with others requires effort, and thus much of what we call prosocial behavior involves the sort of things that deplete the ego. The results of the social exclusion study suggest that when you’ve been rejected by society it’s as if somewhere deep inside you ask, “Why keep regulating my behavior if no one cares what I do?”

You may have felt the urge to shut down your computer, shed your clothes, and walk naked into the woods, but you don’t do it. With differing motivations, many people have famously exited society to be alone: Ted Kaczynski, Henry David Thoreau, Christopher McCandless to name a few. As with these three, most don’t go so far as to shed all remnants of the tools and trappings of modern living. You may decide one day to throw middle fingers at the material world and head into the wild, but you’ll probably keep your shoes on and take a pocket knife at the very least. Just in case of, you know, bears. It’s a compelling idea nonetheless – leaving society with no company. You enjoy watching shows like Survivorman and Man vs. Wild. You revisit tales like Castaway and Robinson Crusoe and Life of Pi. It’s in our shared experience, a curiosity and a fear, the idea of total expulsion from the rest of your kin.

Ostracism is a potent and painful experience. The word comes from a form of serious punishment in ancient Athens and other large cities. The Greeks often expelled those who broke the trust of their society. Shards of pottery, ostracon, were used as voting tokens when a person’s fate was on the ballot. Primates like you survive and thrive because they stick together and form groups, keeping up with those prickly social variables like status and alliance, temperament and skill, political affiliation and sexual disposition prevent ostracism. For a primate, banishment is death. Even among your cousins the chimps, banishment is rare. The only lone chimps are usually ex-alpha males defeated in power takeovers. Chimpanzees will stop hanging out, stop grooming, but they rarely banish. It is likely this has been true of your kind going back for many millennia. A person on their own usually doesn’t make it very long. Your ancestors probably survived not only by keeping away from spiders, snakes, and lions, but also by making friends and not rocking the boat too much back at the village. It makes sense then that you feel an intense, deep pain when rejected socially. You have an innate system for considering that which might get you ostracized. When you get down to it, most of what you know others will consider socially unacceptable are behaviors that would demonstrate selfishness. People who are unreliable, who don’t pitch in, or share, or consider the feelings of others get pushed to the fringe. In the big picture, stealing, raping, murdering, fraud and so on harm others while sating some selfish desire of an individual or a splinter group. Baumeister and his group wrote in the social exclusion paper that being part of society means accepting a bargain between you and others. If you will self-regulate and not be selfish then you get to stay and enjoy the rewards of having a circle of friends and society as a whole, but if you break that bargain society will break its promise and reject you. Your friend groups will stop inviting you to parties, unfollow you on Twitter. If you are too selfish in your larger social group, it might reject you by sending you to jail or worse.

Source: www.unfriendfinder.fr

The researchers in the “no one chose you” study proposed that since self-regulation is required to be prosocial, you expect some sort of reward for regulating your behavior. People in the unwanted group felt the sting of ostracism, and that reframed their self-regulation as being wasteful. It was as if they thought, “Why play by the rules if no one cares?” It poked a hole in their willpower fuel tanks, and when they sat in front of the cookies they couldn’t control their impulses as well as the others. Other studies show when you feel ostracized and unwanted, you can’t solve puzzles as well, you become less likely to cooperate, less motivated to work, more likely to drink and smoke and do other self-destructive things. Rejection obliterates self control, and thus it seems it’s one of the many avenues toward a state of ego depletion.

So, looking back on all of this, what about the nutty propositions put forth by Freud? All of this talk about mental energy, impulses, and cultural judgement sounds a lot like we are validating the ideas of the id, ego, and superego, right? Well, that’s why psychologists have been working so hard to pinpoint what is being depleted when we speak of ego depletion, and it may just be glucose.

A study published in 2010 conducted by Jonathan Leval, Shai Danziger, and Liora Avniam-Pesso of of Columbia and Ben-Guron Universities looked at 1,112 judicial ruling over the course of 10 months concerning prisoner paroles. They found that right after breakfast and lunch, your chances of getting paroled were at their highest. On average, the judges granted parole to around 60 percent of prisoners right after the judge had eaten a meal. The rate of approval crept down after that. Right before a meal, the judges granted parole to about 20 percent of those appearing before them. The less glucose in judges’ bodies, the less willing they were to make the active choice of setting a person free and accepting the consequences and the more likely they were to go with the passive choice to put the fate of the prisoner off until a future date.

The glucose correlation is made stronger by another study by Baumeister in 2007 in which he had people watch a silent video of a woman talking while words flashed in the lower right-hand corner. The subjects’ task was to try as best they could to ignore the words. The scientists tested blood glucose levels before and after the video and compared them to a control group who watched the video without special instructions. Sure enough, the people who avoided the words had lower blood glucose levels after the video than the control group. In subsequent experiments the subjects drank either Kool-aid with sugar or Kool-aid with Splenda right after the video and then proceeded to the sorts of things that tend to reveal ego-depletion in the lab – word puzzles, geometric line tracing puzzles, tests of emotional restraint, tests of suppression of prejudicial attitudes, tests of altruism, etc. The people who thought they got an energy boost tended to perform worse than those who actually got their glucose replenished. Thus, it seems as though you are more able to exert willpower and control, to make decisions and suppress naughtiness by eating and drinking beforehand, which sucks of course if the thing over which you need willpower are food and drink.

It is important to note that this research into what is now being called the resource model of self control is still new and incomplete. In some experiments subjects are able to stave off ego depletion after receiving a gift, a swish of sugar water, or a chance to engage in non-boring tasks, which leads some researchers to believe the reward system of the brain plays a significant role in ego depletion and that glucose is not the only factor. As a wink and a nod to Freud, the idea of ego depletion is still a metaphor for something more complex and nuanced that has yet to be fully understood.

Source: www.publicdomainpictures.net

The current understanding of this is that all brain functions require fuel, but the executive functions seem to require the most. Or, if you prefer, the executive branch of the mind has the most expensive operating costs. Studies show that when low on glucose, those executive functions suffer, and the result is a state of mind called ego depletion. That mental state harkens back to the way Freud and his contemporaries saw the psyche, as a battle between dumb primal desires and the contemplative self. The early psychologists would have said when your ego is weak, your id runs amok. We now know it may just be your prefrontal cortex dealing with a lack of glucose.

Remember, no matter what the self-help books say, the research suggests that willpower isn’t a skill. If it was, there would be some consistency from one task to the next. Instead, every time you exert control over the giant system that is you, that control gets weaker. If you hold back laughter in a church or classroom, every subsequent silly notion is that much funnier until you run the risk of bursting into snorts.

The only way to avoid this state of mind is to predict what might cause it in your own daily life and to avoid those things when you need the most volition. Modern life requires more self control than ever. Just knowing Reddit is out there beckoning your browser, or your iPad is waiting for your caress, or your smart phone is full of status updates, requires a level of impulse control unique to the human mind. Each abstained vagary strengthens the pull of the next. Remember too that you can dampen your executive functions in many ways, like by staying up all night for a few days, or downing a few alcoholic beverages, or holding your tongue at a family gathering, or resisting the pleas of a child for the umpteenth time. Having an important job can lead to decision fatigue which may lead to ego depletion simply because big decisions require lots of energy, literally, and when you slump you go passive. A long day of dealing with bullshit often leads to an evening of no-decision television in which you don’t even feel like switching the channel to get Kim Kardashian’s face out of your television, or sitting and watching a censored Jurassic Park between commercials even though you own a copy of the movie five feet away. If so, no big deal, but if you find yourself in control of someone’s parole or air traffic, or you need to lose 200 pounds, that’s when it’s time to plan ahead. If you want the most control over your own mind so that you can alter your responses to the world instead of giving in and doing what comes naturally, stay fresh. Take breaks. And until we understand just what ego depletion really is, don’t make important decisions on an empty stomach.

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

If you buy one book this year…well, I suppose you should get something you’ve had your eye on for a while. But, if you buy two or more books this year, might I recommend one of them be a celebration of self delusion? Give the gift of humility (to yourself or someone else you love). Watch the trailer.

Order now: Amazon - Barnes and Noble – iTunes – Books A Million

Links and Sources:

The original ego depletion study

A meta-analysis of ego depletion studies

A video of a lecture on ego depletion at New York State University

A study into regulatory depletion patterns

A study asking is self control resembles a muscle

A study attacking the resource model

Restoring the self with with rewards

Study suggesting ego depletion is not just fatigue

The study on social exclusion and self regulation

The study that connected glucose to willpower

An article about quackery in early medicine

Freud and the lady with the runny nose

Oliver Wendell Holmes writes about the early days of medical schools

Bad Medicine: Doctors Doing Harm Since Hippocrates

An 1889 medical school curriculum

A study on rejection among chimpanzees

A New York Times article mentioning Freud’s eels

The study of judges and how meals affect parole

The study of how glucose affects self control

A Wired article on ego depletion by Jonah Leher

A New York Times article on decision fatigue

Baumeister and Tierney answer questions at the Freakonomics blog

December 14, 2011

The Overjustification Effect

The Misconception: There is nothing better in the world than getting paid to do what you love.

The Truth: Getting paid for doing what you already enjoy will sometimes cause your love for the task to wane because you attribute your motivation as coming from the reward, not your internal feelings.

Office Space - Courtesy Twentieth Century Fox

Money isn’t everything. Money can’t buy happiness. Don’t live someone else’s dream. Figure out what you love and then figure out how to get paid doing it.

Maxims like these often find their way into your social media; they arrive in your electronic mailbox at the ends of dense chains of forwards. They bubble up from the collective sighs of well-paid boredom around the world and get routinely polished for presentation in graduation speeches and church sermons.

Money, fame, and prestige – they dangle just outside your reach it seems, encouraging you to lean farther and farther over the edge, to study longer and longer, to work harder and harder. When someone reminds you that acquiring currency while ignoring all else shouldn’t be your primary goal in life, it feels good. You retweet it. You post it on your wall. You forward it, and then you go back to work.

If only science had something concrete to say about the whole thing, you know? All these living greeting cards dispensing wisdom are great and all, but what about really putting money to the test? Does money buy happiness? In 2010, scientists published the results of a study looking into that very question.

The research by Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, analyzed the lives and incomes of nearly half-a-million randomly selected U.S. citizens. They dug through the subjects’ lives searching for indicators of something psychologists call “emotional well being,” a clinical term for how often you feel peaks and valleys like “joy, stress, sadness, anger and affection” and to what degree you feel those things daily. In other words, they measured how happy or sad people were over time compared to how much cash they brought home. They did this by checking if the subjects were consistently able to experience the richness of existence, by whether they were tasting the poetic marrow of life.

The researchers discovered money is indeed a major factor in day-to-day happiness. No surprise there. You need to make a certain amount, on average, to be able to afford food, shelter, clothing, entertainment and the occasional Apple product, but what spun top hats around the country was their finding that beyond a certain point your happiness levels off. The happiness money offers doesn’t keep getting more and more potent – it plateaus. The research showed that a lack of money brings unhappiness, but an overabundance does not have the opposite effect.

According to the research, in modern America the average income required to be happy day-to-day, to experience “emotional well being” is about $75,000 a year. According to the researchers, past that point adding more to your income “does nothing for happiness, enjoyment, sadness, or stress.” A person who makes, on average, $250,000 a year has no greater emotional well-being, no extra day-to-day happiness, than a person making $75,000 a year. In Mississippi it is a bit less, in Chicago a bit more, but the point is there is evidence for the existence of a financiohappiness ceiling. The super-wealthy may believe they are happier, and you may agree, but you both share a delusion.

If you don’t already have it, money can improve your life and make you happier, but once you have enough to go to Red Lobster on Tuesday night without worrying about paying the water bill that month, you’re good to go. Or, as Henry David Thoreau once said, “A man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.” In the modern United States the ability to let most things alone, according to Kahneman and Deaton’s research, costs about $75,000 a year.

If you find that hard to believe, you aren’t alone. A study in 2011 at Cornell asked Americans which they would rather have, more money or more sleep. Most people said more money. In a choice between either $80,000 a year, normal work hours, and about eight hours of sleep a night versus $140,000 a year, routine overtime, and six hours of nightly dreams – the majority of people went with the cash. It’s unfortunate, because although it looks good on paper and feels right in your gut, the research has never agreed. No matter how you turn it, the science says once your basic needs are taken care of, money and other rewards don’t make you happier, and you can appreciate why after examining a psychological jewel called the overjustification effect. To understand it, we must travel to 1973 when a group of psychologists poisoned a few children’s love of drawing in the name of science.

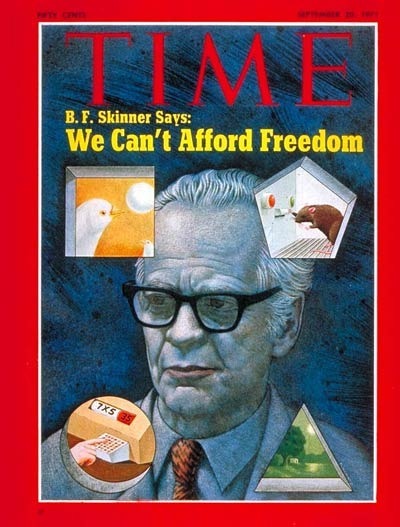

Time Magazine in 1971

Throughout the 20th century, as psychology came into its own as a scientific discipline, many psychologists emerged from the halls of academia and ascended to the rank of celebrity after delivering open-palmed scientific slaps to the face of mankind. Sigmund Freud got people talking about the unconscious and the malleable, hidden world of desires and fears. Carl Jung put the ideas of archetypes, introversion, and extroversion into our vocabulary. Abraham Maslow gave us a hierarchy of needs including hugs and sex. Timothy Leary fed Harvard students psychedelic mushrooms and advocated that an entire generation should use LSD to “turn on, tune in, and drop out.” There are many more, but in the 1970s, B.F. Skinner was the rock star of psychology.

Skinner and his boxes made the cover of Time magazine in 1971 underneath the ominous proclamation, “We Can’t Afford Freedom.” His research into behaviorism had made its way into the public consciousness, and he was intent on using his celebrity to convince all of humanity there was no such thing as free will. You’ve seen his findings in practice. The Supernanny and The Dog Whisperer reward desired behavior and either punish or ignore undesired behavior – and they get impressive results. Skinner could make birds do figure eights on his command, or train them to pilot guided missiles. He invented climate-controlled baby boxes in which infants never cried. He created teaching machines that still influence user interfaces today. But, he also scared a romantic generation of freedom seekers into thinking freedom might be an illusion.

Skinner said all human thoughts and behaviors were just reactions to stimuli – conditioned responses. To believe as Skinner did is to believe everything you do is part of seeking a reward or avoiding a punishment. Your entire life is just a stack of evolutionarily selected against quirks and desires seasoned with programmed interests and fears. There is no self. There is no one in control. Those things are illusions, side effects of a complex nervous system observing its own actions and cognitions. In light of this, Skinner advocated we build a society through setting goals and then condition people toward those goals through positive reinforcement. Skinner didn’t trust human beings not to be lazy, greedy, and violent. Humans, he said, were inclined to seek and reinforce status through institutions, class warfare, and bloodshed. People can’t be trusted with freedom, he told the world. Psychology could instead design systems to condition people toward positive goals that ensure the best possible quality of life for all.

As you might imagine, the proclamation humans have no soul, or at least no special spark, caused a great deal of mental indigestion. Many psychologists resisted the idea that you are nothing more than chemical reactions on top of physical laws playing themselves out no differently than a rock slide crashing down the side of a mountain or a tree converting sunlight and carbon dioxide into wood. Skinner claimed what goes on inside your head is irrelevant, that the environment, the stuff outside your skull determines behavior, thoughts, emotions, beliefs and so on. It was a bold and terrifying claim to many, so science set about the task of picking it apart.

Among those who wanted to know if the mind was just a pile of reactions to rewards and punishments were psychologists Mark Lepper, Daniel Greene and Richard Nisbett. They wondered if thinking about thinking played a bigger role than the behaviorists suggested. In their book, The Hidden Costs of Reward, they detail one experiment in particular which helped pull psychology out from under what they called Skinner’s “long shadow.”

In 1973, Lepper, Greene and Nisbett met with teachers of a preschool class, the sort that generates a steady output of macaroni art and paper-bag vests. They arranged for the children to have a period of free time in which the tots could choose from a variety of different fun activities. Meanwhile, the psychologists would watch from behind a one-way mirror and take notes. The teachers agreed, and the psychologists watched. To proceed, they needed children with a natural affinity for art. So as the kids played, the scientists searched for the ones who gravitated toward drawing and coloring activities. Once they identified the artists of the group, the scientists watched them during free time and measured their participation and interest in drawing for later comparison.

They then divided the children into three groups. They offered Group A a glittering certificate of awesomeness if the artists drew during the next fun time. They offered Group B nothing, but if the kids in Group B happened to draw they received an unexpected certificate of awesomeness identical to the one received by Group A. The experimenters told Group C nothing ahead of time, and later the scientists didn’t award a prize if those children went for the colored pencils and markers. The scientists then watched to see how the kids performed during a series of playtimes over three days. They awarded the prizes, stopped observations, and waited two weeks. When they returned, the researchers watched as the children faced the same the choice as before the experiment began. Three groups, three experiences, many fun activities – how do you think their feelings changed?

Source: Benedikte on Flikr

Well, Group B and Group C didn’t change at all. They went to the art supplies and created monsters and mountains and houses with curly-cue smoke streams crawling out of rectangular chimneys with just as much joy as they had before they met the psychologists. Group A, though, did not. They were different people now. The children in Group A “spent significantly less time” drawing than did the others, and they “showed a significant decrease in interest in the activity” as compared to before the experiment. Why?

The children in Group A were swept up, overpowered, their joy perverted by the overjustification effect. The story they told themselves wasn’t the same story the other groups were telling. That’s how the effect works.

Self-perception theory says you observe your own behavior and then, after the fact, make up a story to explain it. That story is sometimes close to the truth, and sometimes it is just something nice that makes you feel better about being a person. For instance, researchers at Stanford University once divided students into two groups. One received a small cash payment for turning wooden knobs round and round for an hour. The other group received a generous payment for the same task. After the hour, a researcher asked students in each group to tell the next person after them who was about to perform the same boring task that turning knobs was fun and interesting. After that, everyone filled out a survey in which they were asked to say how they truly felt. The people paid a pittance reported the study was a blast. The people paid well reported it was awful. Subjects in both groups lied to the person after them, but the people paid well had a justification, an extrinsic reward to fall back on. The other group had no safety net, no outside justification, so they invented one inside. To keep from feeling icky, they found solace in an internal justification – they thought, “you know, it really was fun when you think about.” That’s called the insufficient justification effect, the yang to overjustification’s yin. In telling themselves the story, the only difference was the size of the reward and whether or not they felt extrinsically or intrinsically motivated. You are driven at the fundamental level in most everything you choose to do by either intrinsic or extrinsic goals.

Intrinsic motivations come from within. As Daniel Pink explained in his excellent book, Drive, those motivations often include mastery, autonomy, and purpose. There are some things you do just because they fulfill you, or they make you feel like you are becoming better at a task, or that you are a master of your destiny, or that you play a role in the grand scheme of things, or that you are helping society in some way. Intrinsic rewards demonstrate to yourself and others the value of being you. They are blurry and difficult to quantify. Charted on a graph, they form long slopes stretching into infinity. You strive to become an amazing cellist, or you volunteer in the campaign of an inspiring politician, or you build the starship Enterprise in Minecraft.

Extrinsic motivations come from without. They are tangible baubles handed over for tangible deeds. They usually exist outside of you before you begin a task. These sorts of motivations include money, prizes and grades, or in the case of punishment, the promise of losing something you like or gaining something you do not. Extrinsic motivations are easy to quantify, and can be demonstrated in bar graphs or tallied on a calculator. You work a double shift for the overtime pay so you can make rent. You put in the hours to become a doctor hoping your father will finally deliver the praise for which you long. You say no to the cheesecake so you can fit into those pants at the Christmas party. If you can admit to yourself that the reward is the only reason you are doing what you are doing – the situps, the spreadsheet, the speed limit – it is probably extrinsic.

Whether a reward is intrinsic or extrinsic helps determine the setting of your narrative – the marketplace or the heart. As Dan Ariely writes in his book, Predictably Irrational, you tend to unconsciously evaluate your behavior and that of others in terms of social norms or market norms. Helping a friend move for free doesn’t feel the same as helping a friend move for $50. It feels wonderful to slip into the same bed with your date after getting to know them and staying up one night making key lime cupcakes and talking about the differences and similarities between Breaking Bad and The Wire, but if after all of that the other person tosses you a $100 bill and says, “Thanks, that was awesome,” you will feel crushed by the terrible weight of market norms. Payments in terms of social norms are intrinsic, and thus your narrative remains impervious to the overjustification effect. Those sorts of payments come as praise and respect, a feeling of mastery or camaraderie or love. Payments in terms of market norms are extrinsic, and your story becomes vulnerable to overjustification. Marketplace payments come as something measurable, and in turn they make your motivation measurable when before it was nebulous, up for interpretation and easy to rationalize.

The deal the children struck with the experimenters ruined their love of art during playtime, not because they received a reward. After all, Group B got the same reward and kept their desire to draw. No, it wasn’t the prize but the story they told themselves about why they chose what they chose, why they did what they did. During the experiment, Group C thought, “I just drew this picture because I love to draw!” Group B thought, “I just got rewarded for doing something I love to do!” Group A thought, “I just drew this to win an award!” When all three groups were faced with the same activity, Group A was faced with a metacognition, a question, a burden unknown to the other groups. The scientists in the knob-turning study and the child artists study showed Skinner’s view was too narrow. Thinking about thinking changes things. Extrinsic rewards can steal your narrative.

As Lepper, Greene and Nisbett wrote, “engagement in an activity of initial interest under conditions that make salient to the person the instrumentality of engagement in that activity as a means to some ulterior end may lead to decrements in subsequent, intrinsic interest in the activity.” In other words, if you are offered a reward to do something you love and then agree, you will later question whether you continue to do it for love or for the reward.

Source: www.trollandtoad.com

In 1980, David Rosenfield, Robert Folger and Harold Adelman at Southern Methodist University revealed a way you can defeat the overjustification effect. Seek employers who dole out reward – paychecks, bonuses, promotions, etc. – based not on quotas or task completions but instead based on competence. They ran an experiment in which they told subjects the goal was to find fun and interesting ways to improve vocabulary skills in schools. They placed participants in two categories and two groups per category. In one category, subjects would be paid for being good at their task. In the other category, the subjects would be paid for completing a task. The subjects received 26 dice with letters on their faces instead of dots and a stack of index cards each with 13 random letters. The subjects hit a timer and used their dice to make words from the letters on the cards. Once they had used nine letters or spent a minute-and-a-half trying, they moved on to the next index card and kept repeating until the experiment ended. It was difficult but fun, and as the players kept going they started to improve in their abilities.

In the payment for competence category, Group A was told they were being payed based on how well they did compared to the average score. In Group B, the subjects were told the same thing, but there was no mention of any reward. In the payment for completion category, the scientists told Group C each completed puzzle would increase their payout, and Group D was told they would be paid by the hour.

After the games, the experimenters pretended to tally up the subjects’ scores and showed Groups A and B how well they did. No matter how they actually performed, the scientists told half of Groups A and B they did poorly and half they were amazing at the game. Groups C and D, the ones who were paid for completions, were also split. Half got low pay and half high pay. The subjects then filled out a questionnaire and sat alone in the room with the dice and cards for three minutes. During that alone time the real study began. The scientists wanted to see who would keep playing the game for fun and for how long.

The people in Groups A and B, the ones who were paid for being better than average, they picked up the game and played it for over two minutes, but slightly less than that if they were told they weren’t that good. The people in groups C and D, the ones paid for completions, didn’t play it for fun for as long as did the people in the competency groups, and they tended to play longer the less they were paid.

The results of the study suggested when you get rewarded based on how well you perform a task, as long as those reasons are made perfectly clear, rewards will generate that electric exuberance of intrinsic validation, and the higher the reward, the better the feeling and the more likely you will try harder in the future. On the other hand, if you are getting rewarded just for being a warm body, no matter how well you do your job, no matter what you achieve, the electric feeling is absent. In those conditions greater rewards don’t lead to more output, don’t encourage you to strive for greatness. Overall, the study suggested rewards don’t have motivational power unless they make you feel competent. Money alone doesn’t do that. With money, when you explain to yourself why you worked so hard, all you can come up with is, “to get paid.” You come to believe you are being coerced, paid off, bought out. In the absence of what the scientists called “competency feedback” there is no story to tell yourself that paints you as a badass. Quotas and overtime and hourly pay don’t offer such indications of competency. Bonuses based on a reaching a specific number of completions or reaching a quantified goal make you feel like a machine.

If you pay people to complete puzzles instead of paying them for being smart, they lose interest in the game. If you pay children to draw, fun becomes work. Payment on top of compliments and other praise and feeling good about personal achievement are powerful motivators, but only if they are unexpected. Only then can you continue to tell the story that keeps you going; only then can you still explain your motivation as coming from within.

Consider the story you tell yourself about why you do what you do for a living. How vulnerable is that tale to these effects?

Maybe your story goes like this: Work is just a means to an end. You go to work; you get paid. You exchange effort for survival tokens and the occasional steampunk thong from Etsy. Work is not fun. Work pays bills. Fun happens at places that are not work. Your story is in no danger if that’s how you see things. In an environment like that Skinner’s assumptions hold true, you will only work as hard as is necessary to keep getting paychecks. If offered greater rewards, you’ll work harder for them.

Maybe your story goes like this though: I love what I do. It changes lives. It makes the world a better place. I am slowly becoming a master in my field, and I get to choose how I solve problems. My bosses value my efforts, depend on me, and offer praise. In that scenario, rewards just get in the way of your job. As Kahneman’s and Deaton’s study about happiness showed, once you earn enough to be happy day-to-day, motivation must come from something else. As Kahneman and Deaton’s research into happiness and money showed, the only material reward worth seeking once you have a bed, running water and access to microwave popcorn, are tributes, symbols to all of your merit, stuff that demonstrates your effectance to yourself and others. Ranks, degrees, gold stars, trophies, Nobel Prizes and Academy Awards – these are shorthand indicators of your competence. Those rewards amplify your internal motivations; they build your self-esteem and strengthen your feelings of self-efficacy. They show you’ve leveled up in the real world. Achievement unlocked. They help you construct a personal narrative you enjoy telling.

The overjustification effect threatens your fragile narratives, especially if you haven’t figured out what to do with your life. You run the risk of seeing your behavior as motivated by profit instead of interest if you agree to get paid for something you would probably do for free. Conditioning will not only fail, it will pollute you. You run the risk of believing the reward, not your passion, was responsible for your effort, and in the future it will be a challenge to generate enthusiasm. It becomes more and more difficult to look back on your actions and describe them in terms of internal motivations. The thing you love can become drudgery if that which can’t be measured is transmuted into something you can plug into TurboTax.

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

Give the gift of humility (to yourself or someone else you love). Y ou can bring You Are Not So Smart into meatspace by transmuting its electrons and photons into ink and paper. Just exchange some survival tokens with a trusted merchant and you’ll own a celebration of self delusion – and you’ll help keep this website going.

Learn more about the book | Watch the trailer | Watch the other trailer

Order now: Amazon - Barnes and Noble - iTunes - Books A Million - IndieBound - Audible

Links:

The Starship Enterprise in Minecraft

The WSJ’s Writeup on the Happiness Study

Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being

The Official Website of B.F. Skinner

RSA Animate: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us

Steve Jobs’ Commencement Speech at Stanford

A Meta-Analysis of The Overjustification Effect

November 2, 2011

Free Signed Bookplates – Free Kindlegraphs

Concerning the book – the bookplate offer has been a great success (as evidenced by those beautiful faces up there), so now you can get a free, signed bookplate just by sending a self-addressed, stamped envelope to…

Signed Bookplate

P.O. Box 15792

Hattiesburg, MS 39404

…and I’ll send you back one of these with my scribbles on it. Sorry, U.S.A. only.

If you would like a free chapter, Kindle owners can download a free sample chapter from the Kindle store at Amazon.

If you would like your Kindle copy of YANSS signed, just head to this link.

You can also read excerpts at Boing Boing, The Atlantic, Gawker, and the New York Post. If you want a review, check out this one at Brain Pickings or this one at the Onion A.V. Club. Lastly, I’m partnering with the awesome and popular Now I Know newsletter – subscribers will now be getting fresh YANSS content in addition to the other cool stuff Dan Lewis puts out.

October 5, 2011

The Benjamin Franklin Effect

The Misconception: You do nice things for the people you like and bad things to the people you hate.

The Truth: You grow to like people for whom you do nice things and hate people you harm.

Benjamin Franklin knew how to deal with haters.

Benjamin Franklin knew how to deal with haters.

Born in 1706 as the eighth of 17 children to a Massachusetts soap and candlestick maker, the chances Benjamin would go on to become a gentleman, scholar, scientist, statesman, musician, author, publisher and all-around general bad-ass were astronomically low, yet he did just that and more because he was a master of the game of personal politics.

Like many people full of drive and intelligence born into a low station, Franklin developed strong people skills and social powers. All else denied, the analytical mind will pick apart behavior, and Franklin became adroit at human relations. From an early age, he was a talker and a schemer – a man capable of guile, cunning and persuasive charm. He stockpiled a cache of cajolative secret weapons, one of which was the Benjamin Franklin Effect, a tool as useful today as it was in the 1730s and still just as counterintuitive. To understand it, let’s first rewind back to 1706.

Franklin’s prospects were dim. With 17 children, Josiah and Abiah Franklin could only afford two years of schooling for Benjamin. Instead, they made him work, and when he was 12 he became an apprentice to his brother James who was a printer in Boston. The printing business gave Benjamin the opportunity to read books and pamphlets. It was as if Ben Franklin was the one kid in the neighborhood who had access to the Internet. He read everything, and taught himself every skill and discipline one could absorb from text.