David McRaney's Blog, page 31

November 24, 2014

YANSS 037 – Drive, Motivation, and Crowd Control with Daniel Pink

The Topic: Motivation

The Guest: Daniel Pink

The Episode: Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

A scene from Office Space – 20th Century Fox

This episode is brought to you by Lynda, an easy and affordable way to help individuals and organizations learn. Try Lynda free for 7 days.

This episode also brought to you by Squarespace. For a free trial and 10% off enter offer code LESSDUMB at checkout.

Why do you work where you work? I mean, specifically, why do you do whatever it is that you do for a living?

I’m pretty sure that you can answer this question. The average person, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, spends between 11 and 15 years of his or her life at work. On the high end, that’s about a fifth of your time on Earth as a person capable of enjoying pumpkin pie and movies about robots. That’s a lot of time spent doing something for reasons unknown, so I doubt you would lift your shoulders and offer up open palms of confusion when it comes to this question. I’m just not so sure that the answer you come up with will be correct.

You probably know all about intrinsic versus extrinsic rewards and the other behavioral motivations like your basic drives for food, sex, and social acceptance as well as the pursuit of pleasure over pain and the quest for your other emotional needs. You know that intrinsic rewards satisfy these desires directly, while extrinsic rewards are usually tokens you can later trade for satisfaction. So, knowing all of this, it’s likely very easy for you to explain your motivations for attending all those meetings and answering all those emails before putting on all those shoes after shaving all the those places before commuting all those miles. Still, I’m not sure I believe you.

Two of my favorite studies in psychology illustrate why I’m a bit skeptical about your justification for your actions – the story you tell yourself and others when wondering why you do what you do.

In one experiment, Leon Festinger and his colleagues brought college students into a room where those students, one at a time, sat across from a scientist in a lab coat who took notes while holding a stopwatch. The researcher asked these students to place wooden spools on a serving tray until it could hold no more, and then take them all back off again. After a while, the same people moved on to a second task in which they rotated a wooden peg round and round a quarter-turn at a time. Altogether, the students spent one incredibly boring hour doing mindless tasks, and after it was all over the scientist asked if the student in each run of the experiment would, before leaving, tell the next person waiting to do those same tasks that the experiment overall was fun and interesting. Every student did, and then, as a final task, each student was asked to write a brief essay explaining how he truly felt. The students didn’t know they had been divided into two groups. Some students had received the equivalent of about $8 before the experiment began, and the others received what would be about $150 in today’s money. Even though every other part of the experiment was identical, the difference in pay completely changed what the students wrote in those essays. The $150 group said the experiment was awful and tedious, something they would rather not do again. The $8 group said it was actually kind of neat, meditative and relaxing, and kind of fun when you think about it. Why the difference? Festinger said the two groups looked back on their actions and felt icky about lying. There was no congruence between what they had done and what they had said to the stranger, so to come into congruence they needed some sort of justification they could plug into their narratives. One group had $150 as justification, and so they were free to be honest with themselves. They did it for the money. They lied. The task was terrible. The other group didn’t have such an easy way out of those bad feelings, so they reframed the experience. I wouldn’t lie for a measly $8, each one thought. It was sort of pleasant really, so actually I didn’t lie after all. Two realities formed in two groups of people, and the only difference was how much compensation they received.

The other experiment was conducted by Mark Lepper, Daniel Greene and Richard Nisbett. They went to a preschool and observed children playing during free time. They noted which children tended to be most interested in art supplies – drawing, coloring, and painting – and then divided those children into three groups. Group A was told that over the next three days every time they chose an art activity during free time they would receive a heap of praise and a certificate of achievement. Group B wasn’t told this ahead of time, but when they chose to draw, paint, or color, they were surprised with the award and the praise just like group A. Group C was allowed to just keep playing as usual, no rewards. After the observation the scientists waited three weeks and then returned to measure how often each of the children in the three groups were now choosing art activities on his or her own. Upon return, they found that groups B and C were no different than before, but children in Group A were now significantly less likely to play with the art supplies than they were before the experiment began. The researchers explained that even though the activities were exactly the same for all three groups both before and after, only group A had reframed the experience to now be about rewards. They saw themselves as painting for praise, drawing for the sake of a payment. It was work. Even with those incentives no longer in place, the story some preschoolers told themselves had been tainted while the story for the children in the other groups had not.

Psychologists call these two phenomenon insufficient justification and overjustification, two extremes on the spectrum of internal storytelling. In one scenario a lack of an extrinsic reward, cash for lying, led to the invention of an intrinsic one that rewrote the entire experience. In the other scenario, a new way of looking at a beloved activity robbed children of an intrinsic reward, the joy of creation, and replaced it with an extrinsic one, pay for play. In both experiments, the brains of the people involved adopted new behaviors and perspectives without them knowing it.

That’s why I’m not sure you know why you do the work that you do. Rewards, both intrinsic and extrinsic, can scramble our narratives and justifications, and so the stories we tell ourselves can become weird fictions that keep us going, not that this is a bad thing. It’s just that we tend to believe we have access to the motivations behind our actions, and we tend to believe we know the source of our emotions and drives, but the truth is that we often do not have access to this information despite how easy it seems to come up with rational explanations as if we did.

This presents a problem for employers who want to build better workplaces and employees who want to enjoy their 11 to 15 years of life working in those workplaces. If people don’t know what drives them, and employers don’t know how to incentivize people to be more engaged, and overall we have a terrible grasp of how to be fulfilled and happy in our work, yet everyone kind of thinks they know what they are doing even though they don’t, then what should we be doing instead? Well, the good news is that this whole system of rewards, incentives, motivations, and related phenomena has been studied for long enough that psychology and neuroscience have some practical, actionable advice for workplaces and individuals when it comes to harnessing our motivations and drives.

Our guest in this episode of the You Are Not So Smart podcast is Daniel Pink, author of the book “Drive” and the host of the new National Geographic show “Crowd Control.” In Drive, Pink writes about how many businesses and institutions depend on folklore instead of science to encourage people to come to work and be creative. He explains that the greatest incentives, once people are paid a decent wage, are autonomy, mastery, and purpose – intrinsic rewards that workplaces can easily offer if they choose to change the way they incentivize employees. In Crowd Control, Pink explores how, by paying attention to what science tells us truly motivates people, we can change the way we do things from giving out speeding tickets to managing baggage claims at airports so that we alter people’s behavior for the benefit of everyone. In the interview Pink details what he’s learned from both projects when it comes to what truly motivates us.

Our guest in this episode of the You Are Not So Smart podcast is Daniel Pink, author of the book “Drive” and the host of the new National Geographic show “Crowd Control.” In Drive, Pink writes about how many businesses and institutions depend on folklore instead of science to encourage people to come to work and be creative. He explains that the greatest incentives, once people are paid a decent wage, are autonomy, mastery, and purpose – intrinsic rewards that workplaces can easily offer if they choose to change the way they incentivize employees. In Crowd Control, Pink explores how, by paying attention to what science tells us truly motivates people, we can change the way we do things from giving out speeding tickets to managing baggage claims at airports so that we alter people’s behavior for the benefit of everyone. In the interview Pink details what he’s learned from both projects when it comes to what truly motivates us.

After the interview, I discuss a news story about delayed acting out to changes in the workplace.

In every episode, before I read a bit of self delusion news, I taste a cookie baked from a recipe sent in by a listener/reader. That listener/reader wins a signed copy of my new book, “You Are Now Less Dumb,” and I post the recipe on the YANSS Pinterest page. This episode’s winner is Marshall Schott who submitted a recipe for pumpkin pie snickerdoodles. Send your own recipes to david {at} youarenotsosmart.com.

Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

Office stress? Workers may wait before acting out

November 10, 2014

YANSS Podcast 036 – Why We Are Unaware that We Lack the Skill to Tell How Unskilled and Unaware We Are

The Topic: The Dunning-Kruger Effect

The Guest: David Dunning

The Episode: Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

A scene from NBC’s “The Office”

This episode is brought to you by Stamps.com – where is the fun in living in the future if you still have to go to the post office? Click on the microphone and enter “smart” for a $110 special offer.

This episode is also brought to you by Lynda, an easy and affordable way to help individuals and organizations learn. Try Lynda free for 7 days.

Here’s a fun word to add to your vocabulary: nescience. I ran across it a few months back and kind of fell in love with it.

It’s related to the word prescience, which is a kind of knowing. Prescience is a state of mind, an awareness, that grants you knowledge of the future – about something that has yet to happen or is not yet in existence. It’s a strange idea isn’t it, that knowledge is a thing, a possession, that it stands alone and in proxy for something else out there in reality that has yet to actually…be? Then, the time comes, and the knowledge is no longer alone. Foreknowledge becomes knowledge and now corresponds to a real thing that is true. It is no longer pre-science but just science.

I first learned the word nescience from the book Ignorance and Surprise by Matthias Gross. That book revealed to me that, philosophically speaking, ignorance is a complicated matter. You can describe it in many ways. In that book Gross talks about the difficulties of translating a sociologist named Georg Simmel who often used the word “nichtwissen” in his writing. Gross says that some translations changed that word to nescience and some just replaced it with “not knowing.” It’s a difficult to term to translate, he explains, because it can mean a few different things. If you stick to the Latin ins and outs of the word, nescience means non-knowledge, or what we would probably just call ignorance. But Gross writes that in some circles it has a special meaning. He says it can mean something you can’t know in advance, or an unknown unknown, or something that no human being can ever hope to know, something a theologian might express as a thought in the mind of God. For some people, as Gross points out, everything is in the mind of God, so therefore nothing is actually knowable. To those people nescience is the natural state of all creatures and nothing can ever truly be known, not for sure. Like I said, ignorance is a complex concept.

It’s that last meaning of nescience that I think is most fun. Take away the religious aspect and nescience is prescience in negative. It is the state of not knowing, but stronger than that. It’s not knowing something that can’t be known. It’s not even knowing that you can’t know it. For instance, your cat can never read or understand the latest terms and conditions for iTunes, thus if she clicked on “I Agree,” we wouldn’t consider that binding. There are vast expanses of ignorance that your cat can’t even imagine, much less gain the knowledge about those things required to rid herself of that ignorance. That’s the definition of nescience I prefer.

I love this word, because once you accept this definition you start to wonder about a few things. Are there some things that, just like my cat, I can never know that I can never know? Are there things that maybe no one can ever know that no one can ever know? It’s a fun, frustrating, dorm-room-bong-hit-whoa-dude loop of weirdness that real philosophers and sociologists seriously ponder and continue to write about in books you can buy on Amazon.

I think I like this idea because I often look back at my former self and imagine what sort of advice I would offer that person. It seems like I’m always in a position to do that, no matter how old I am or how old the former me is in my imagination. I was always more ignorant than I am now, even though I didn’t feel all that ignorant then. That means that it’s probably also true that right now I’m sitting here in a state of total ignorance concerning things that my future self wishes he could shout back at me through time. Yet here I sit, unaware. Nescient.

The evidence gathered so far by psychologists and neuroscientists seems to suggest that each one of us has a relationship with our own ignorance, a dishonest, complicated relationship, and that dishonesty keeps us sane, happy, and willing to get out of bed in the morning. Part of that ignorance is a blind spot we each possess that obscures both our competence and incompetence.

Psychologists David Dunning and Joyce Ehrlinger once conducted an experiment investigating how bad people are at judging their own competence. Specifically, they were interested in people’s self-assessment of a single performance. They wrote in the study that they already knew from previous research that people seemed to be especially prone to making mistakes when they judged the accuracy of their own perceptions if those perceptions were of themselves and not others. To investigate why, they created a ruse.

In the study, Dunning and Ehrlinger describe how they gathered college students together who agreed to take a test. All the participants took the exact same test – same font, same order, same words, everything – but the scientists told one group that it was a test that measured abstract reasoning ability. They told another group it measured computer programming ability. Two groups of people took the same exam, but each batch of subjects believed it was measuring something unique to that group. When asked to evaluate their own performances, the people who believed they had taken a test that measured reasoning skills reported back that they felt they did really well. The other group, however, the ones who believed they had taken a test that measured computer programming prowess, weren’t so sure. They guessed that they did much poorer on the test than did the other group – even though they took the same test. The real results actually showed both groups did about the same. The only difference was how they judged their own performances. The scientists said that it seemed as though the subjects weren’t truly judging how well they had done based on any ease or difficulty they may have experienced during the test itself, but they were inferring how well they had performed based on the kind of people they believed themselves to be.

Dunning and Ehrlinger knew that most college students tend to hold very high opinions of themselves when it comes to abstract reasoning. It’s part of what they call a “chronic self view.” You have an idea of who you are in your mind, and it is kind of like a character in a story, the protagonist in the tale of your life. Some aspects of that character are chronic, traits that are always there that you feel are essential and evident, beliefs about your level of skill that are consistent across all situations. For most college students, being great at abstract reasoning is one of those traits, but being great at computer programming is not.

Dunning and Ehrlinger write that the way you view your past performances can greatly affect your future decisions, behaviors, judgments, and choices. They bring up the example of a first date. How you judge your contribution to the experience might motivate you to keep calling someone who doesn’t want to ever see you again, or it might cause you to miss out on something wonderful because you mistakenly think the other person hated every minute of the night. In every aspect of our lives, they write, we are evaluating how well we performed and using that analysis to decide when to continue and when to quit, when to try harder and work longer and when we can sit back and rest because everything is going just fine. Yet, the problem with this is that we are really, really bad at this kind of analysis. We are nescient. The reality of our own abilities, the level of our own skills, both when lacking and when excelling, is often something we don’t know that we don’t know.

Dunning and Ehrlinger put it like this, “In general, the perceptions people hold, of either their overall ability or specific performance, tend to be correlated only modestly with their actual performance.” We must manage our own ignorance when reflecting on any performance – a test, an athletic event, a speech, or even a conversation. Whether modest or confident, you often depend on the image you maintain of yourself as a guide for how well you did more than actual feedback. To make matters worse, you often don’t get any feedback, or you get a bad version of it.

In the case of singing, you might get all the way to an audition on X-Factor on national television before someone finally provides you with an accurate appraisal. Dunning says that the shock that some people feel when Simon Cowell cruelly explains to them that they suck is often the result of living for years in an environment filled with mediocrity enablers. Friends and family, peers and coworkers, they don’t want to be mean or impolite. They encourage you to keep going until you end up in front of millions reeling from your first experience with honest feedback.

When you are unskilled yet unaware, you often experience what is now known in psychology as the Dunning-Kruger effect, a psychological phenomenon that arises sometimes in your life because you are generally very bad at self-assessment. If you have ever been confronted with the fact that you were in over your head, or that you had no idea what you were doing, or that you thought you were more skilled at something than you actually were – then you may have experienced this effect. It is very easy to be both unskilled and unaware of it, and in this episode we explore why that is with professor David Dunning, one of the researchers who coined the term and a scientist who continues to add to our understanding of the phenomenon.

When you are unskilled yet unaware, you often experience what is now known in psychology as the Dunning-Kruger effect, a psychological phenomenon that arises sometimes in your life because you are generally very bad at self-assessment. If you have ever been confronted with the fact that you were in over your head, or that you had no idea what you were doing, or that you thought you were more skilled at something than you actually were – then you may have experienced this effect. It is very easy to be both unskilled and unaware of it, and in this episode we explore why that is with professor David Dunning, one of the researchers who coined the term and a scientist who continues to add to our understanding of the phenomenon.

After the interview, I discuss a news story about how people overestimate how awesome they look when bragging and underestimate how much people hate hearing you toot your own horn.

In every episode, before I read a bit of self delusion news, I taste a cookie baked from a recipe sent in by a listener/reader. That listener/reader wins a signed copy of my new book, “You Are Now Less Dumb,” and I post the recipe on the YANSS Pinterest page. This episode’s winner is Janelle Robichaud who submitted a recipe for sunshine cookies. Send your own recipes to david {at} youarenotsosmart.com.

Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

Scientific Evidence That Self-Promoters Underestimate How Annoying They Are

20 Minutes of X-Factor Auditions

November 3, 2014

YANSS Podcast 035 – Sunk Costs and the Pain of Vain

The Topic: The Sunk Cost Fallacy

The Episode: Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

This episode is brought to you by Lynda, an easy and affordable way to help individuals and organizations learn. Try Lynda free for 7 days.

Every once in a while you will ask yourself, “I wonder if I should quit?”

Should you quit your job? Should you end your relationship? Should you abandon your degree? Should you shut down this project?

These are difficult questions to answer. If you are like me, every time you’ve heard one of those questions emerge in your mind, it lingered. It began to echo right as you woke up and just as pulled the covers over your shoulders. In the shower, waiting in line, in all your quiet moments – a question like that will appear behind your eyes, pulsating like a giant neon billboard until you can work out your decision.

Oddly enough, as a human being, that decision is often not made any easier when quitting is the most logical course of action. Even if it is obvious that it is no longer worth your time to keep going, your desire to plod on and your reluctance to quit are both muddled by an argumentative loop inside which you and many others easily get stuck.

The same psychological hooks that cost companies millions of dollars to produce products obviously destined to fail can also keep troops in harm’s way long past the point when the whole war effort should be brought to an end. It’s a universal human tendency, the same one that influences you to keep watching a bad movie instead of walking out of the theater in time to catch another or that keeps you planted in your seat at a restaurant after you’ve been waiting thirty minutes for your drinks. If you reach the end of the quest, you think, then you haven’t truly lost anything, and that is sometimes a motivation so strong it prolongs horrific, bloody wars and enormously expensive projects well past the point when most people involved in efforts like those have felt a strong intuition that no matter the outcome, at this point, total losses will exceed any potential gains.

In this episode of the You Are Not So Smart Podcast, we explore the sunk cost fallacy, a strangely twisted bit of logic that seems to pop into the human mind once a person has experienced the pain of loss or the ickiness of waste on his or her way toward a concrete goal. It’s illogical, irrational, unreasonable – and as a perfectly normal human being, you act under its influence all the time.

LINKS

Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

Liberal or conservative? Brain responses to disgusting images help reveal political leanings

SOURCES

Ariely, D. (2009). Predictably irrational, revised and expanded edition: The hidden forces that shape our decisions. Harper. (Amazon link)

Arkes, Hal R., and Peter Ayton. “The Sunk Cost and Concorde Effects: Are Humans Less Rational than Lower Animals?” Psychological Bulletin 125.5 (1999): 591-600. Print. (pdf)

Burthold, G. R. (2008). Psychology of decision making in legal, health care and science settings. Gardners Books. (Google Books link)

Busch, Jack. “Travel Zen: How to Avoid Making Your Vacation Seem Like Work.” Primer Magazine. Primer Magazine, Jan. 2009. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Gaming Can Make a Better World. By Jane McGonigal. TED Talks. TED Conferences, LLC, Feb. 2010. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Godin, Seth. “Ignore Sunk Costs.” Seth’s Blog. Typepad, Inc., 12 May 2009. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Höffler, Felix. “Why Humans Care About Sunk Costs While (Lower) Animals Don’t.” The Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods, 31 Mar. 2008. Web. Mar. 2011. (pdf)

Indvik, Lauren. “FarmVille” Interruption Cited in Baby’s Murder.” Mashable. Mashable Inc., 28 Oct. 2010. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. (Amazon link)

Kushner, David. “Games: Why Zynga’s Success Makes Game Designers Gloomy.” Wired. Conde Nast Digital, 27 Sept. 2010. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Lehrer, Jonah. “Loss Aversion.” ScienceBlogs. ScienceBlogs LLC, 10 Feb. 2010. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Schwartz, Barry. “The Sunk-Cost Fallacy Bush Falls Victim to a Bad New Argument for the Iraq War.” Slate. The Slate Group, 09 Sept. 2005. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Shambora, Jessica. “‘FarmVille’ Gamemaker Zynga Sees Dollar Signs.” CNN Money. Cable News Network, 26 Oct. 2009. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Vidyarthi, Neil. “City Council Member Booted For Playing Farmville.” SocialTimes. Web Media Brands Inc., 30 Mar. 2010. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Walker, Tim. “Welcome to FarmVille: Population 80 Million.” Independent. Independent Digital News and Media, 22 Feb. 2010. Web. Mar. 2011.

“Why Zynga’s Success Makes Game Designers Gloomy | Discussion at Hacker News.” Hacker News. Y Combinator, 7 Oct. 2010. Web. Mar. 2011 (link)

Wittmershaus, Eric. “Facebook Game’s Cautionary Tale.” GameWit. Press Democrat Media Co., 04 Aug. 2010. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

Yang, Sizhao Zao. “How Did FarmVille Take over FarmTown, When It Was Just a Exact Duplicate of FarmTown and FarmTown Was Released Much Earlier?” Quora. Quora, Inc., 01 Jan. 2011. Web. Mar. 2011. (link)

October 14, 2014

YANSS Podcast 034 – After This, Therefore Because of This: Your Weird Relationship with Cause and Effect

The Topic: The Post Hoc Fallacy

The Episode: Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

This episode brought to you by Squarespace. For a free trial and 10% off enter offer code LESSDUMB at checkout.

And by Lynda, an easy and affordable way to help individuals and organizations learn. Try Lynda free for 7 days.

When I was a boy, I spent my summers with my grandparents. They, like many Southerners, had a farm populated with animals to eat and animals to help. It was everywhere alive with edible plants – fields of corn and cucumbers and peas and butterbeans and peanuts, and throngs of mysterious life from stumps claimed by beds of ants to mushroom fairy rings, living things tending to business without our influence.

Remembering it now, I can see the symmetry of the rows, and the order of the barns, the arrangement of tools, the stockpiles of feed. I remember the care my grandmother took with tomatoes, nudging them along from the soil to the Ball jars she boiled, sealing up the red, seedy swirls under lids surrounded by brass-colored shrink bands. I remember my grandfather erecting dried and gutted gourds on polls so Martins would come and create families above us and we wouldn’t suffer as many mosquito bites when shelling peas under the giant pecan tree we all used for shade.

For me, the wonder of that life, even then, was in how so much was understood about cause and effect, about what was to come if you prepared, took care, made a particular kind of effort. It was as if they borrowed the momentum of the natural world instead of trying to force it one way or the other, like grabbing a passing trolley and hoisting yourself on the back.

This relationship with cause and effect was not perfect, not that I knew that then. In fact, my grandparents had a collection of books about cause and effect that I adored called Foxfire. They looked like encyclopedias, and they were numbered. Foxfire 1, 2, 3, etc. Looking them up just before writing this, I discovered they were actually anthologies of an old Appalachian magazine. An article in the Christian Science Monitor from 1983 and an entry at the Georgia Encyclopedia website both say the contents of the magazines came from interviews with people who were already old in the 1960s, people from around the South who shared folktales and folk knowledge and folk remedies and methods of borrowing that same momentum that my grandparents busied themselves pursuing.

My grandparents considered the Foxfire books correct and accurate and worthy of study, reference, and reverence. They were second only to the Bibles resting beside the beds in several rooms. They only had one worn copy of each of the Foxfire books, but as a whole they had their own shelf, just outside the kitchen. What could you find inside them? Rural tips and tricks to tackle the harsh wilderness. What you would call life hacks today, except concerning moonshine and planting crops. Some advice was great, passed down for generations and finally captured in an interview for the magazine right at the end of other people’s grandparents’ lives. A lot of the advice wasn’t so great, though as a boy I never noticed any suspicion or skepticism among my family. A hacking cough, said one Foxfire book, could be cured by swallowing a wad of local spiderwebs. That one I remembered. Others I didn’t, but they came hurtling back to me once I looked at the contents on Amazon today. I saw entries on “Snake Lore” and faith healing but also sections on how to make soap and butter, and how to build sturdy log cabins. It’s a mix of things that seemed to work. Some of it true wisdom, and a lot of it completely wrong. Those Foxfire books, and the life my grandparents led, was prescientific and irrational, but most of the time it produced results. The bits that are wrong, and downright bizarre, make me smirk while I push up my glasses from behind this computer, but then I remember that the only time my grandparents visited the grocery store was to buy things like milk, beef, and cheese since they no longer had the energy to deal with cattle. Other than that, well until their 70s, they very nearly lived completely off the land, which is something I couldn’t do today.

The Foxfire books, and the lives of the sort of people whose knowledge is captured within, are another testament to how we have always depended on good-enough solutions to the complexities of decisions, judgments, and reasoning. Whether or not the people practicing these techniques for decades and longer knew for sure they had pinpointed the causes to the effects they were seeking, things tended to work out anyway. Do spider webs cure coughs? No. Does your cough get better after you eat them? Yes. It’s no different than the zillions of remedies I see floating on the web right now from wine to chocolate to gluten abstinence and paleolithic dining. We mess up all the time when it comes to cause and effect, but it usually doesn’t lead to enough harm to notice. In general, over many generations, we’ve gotten by because more often than not the system works well. It might not get you to the moon, but it will keep you alive and full of butterbeans. Also, you might be burned as a witch.

In modern times, when the system hasn’t worked out well, it once led to one of my favorite mental pratfalls of all time. A few years ago, Bill Clinton bought and wore in public a magical amulet.

That’s right, magical amulet. There isn’t a single entry in those Foxfire books, not a solitary nugget of folk wisdom my grandparents could have offered up that is any less wacky than the Power Balance Bracelet. A band of silicone with a tiny hologram affixed to the side that, according to the manufacturer, enhances natural energy fields and provides balance to the wearer as he or she comes into resonance with the hologram. The result? Better athletic performance. Well, that’s what the company used to claim, but that was before they lost a $67 million lawsuit and had to publicly state, “We admit that there is no credible scientific evidence that supports our claims and therefore we engaged in misleading conduct…” Now the company makes ambiguous claims about “Eastern philosophies.” You can find Drew Brees of the New Orleans Saints endorsing the enchanted bracelets of power at the company’s website right now. He prefers the black collection made with “surgical grade silicone.”

The Power Balance bracelets were debunked thanks to scientific research, much of it conducted in Australia and Wales. The results showed that they had no more power than any other bracelet charged with meaning and supported by belief. No doubt, most of the contents of the Foxfire collection have yet to receive a similar level of scrutiny.

Who wore the power bracelets in their heyday? At least one former president, a slew of professional athletes, and one third of my uncles. Enough people to make the company more than $30 million in 2011, according to the Associated Press. Presumably, all of them intelligent, reasonable people who had no problem with the idea of a factory that employs wizards.

Still, the Power Balance bracelet is just another in a long line of magical items and alternative cures that people have fallen for since there have been people, and there will be many more thanks to the post hoc fallacy. After this, therefore because of this – that’s the fallacy. It’s a rule of thumb, a heuristic, that guided my grandparent’s farm, filled the Foxfire books, and for the most part got human beings out of the nomadic lifestyle and into yoga, but it isn’t perfect. Whether you go to the doctor for your cold, or you decide to eat a ball of cobwebs, or eat nothing but grapefruit for a week, your cold will get better. Which one then is the true cure? Maybe all of them. Maybe none. That’s our predicament. We are stuck with this weird brain that’s so bad at pinpointing cause and effect that one of us can run an entire country, give rousing speeches that change the world, yet not possess the skepticism required to prevent him from handing over $30 for a hologram with a magic spell inside.

On this episode of the You Are Not So Smart Podcast, you’ll learn a lot more about the Power Balance Bracelet as we explore the post hoc fallacy, and how it leads to all sorts of things from pressing disconnected crosswalk buttons to rubbing your nipples with frozen cabbage.

At the end of the episode we discuss a recent study that suggests men drink so that their smiles become contagious.

NOTE: Some of this content is material researched for and written about in a chapter in my second book You Are Now Less Dumb.

Links

Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

Alcohol Makes Smiles More “Contagious,” but Only for Men

Sources

• Arabe, Katrina C. “”Dummy” Thermostats Cool Down Tempers, Not Temperatures.” ThomasNet News. Thomas Publishing Company, 11 Apr. 2003. Web. Sept. 2012.

•Associated Press. “Power Balance: Bracelets Don’t Work.” ESPN. ESPN Internet Ventures., 04 Jan. 2011. Web. Sept. 2012. Bathe, Carrlyn. “The Ice Crew’s Lucky Charms.” FOX Sports West. FOX Sports Interactive Media, LLC., 08 Mar. 2012. Web. Sept. 2012.

• Brice, S. R., B. S. Jarosz, R. A. Ames, J. Baglin, and C. Da Costa. “The Effect of Close Proximity Holographic Wristbands on Human Balance and Limits of Stability: A Randomised, Placebo-controlled Trial.” Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 15.3 (2011): 298-303. Print.

• Callahan, Gerry. “Cheers Wade’s World Back in Town.” Boston Herald 21 May 1993, Sports sec.: 112. Print. Damisch, L., B. Stoberock, and T. Mussweiler. “Keep Your Fingers Crossed!: How Superstition Improves Performance.” Psychological Science 21.7 (2010): 1014-020. Print.

• “Goran Ivanisevic Quotes.” Goran Online. Web. Sept. 2012. Hutson, Matthew. “In Defense of Superstition.” The New York Times 08 Apr. 2012: SR5. NYTimes. The New York Times Company, 06 Apr. 2012 Web.

•Kaptchuk, Ted J., Elizabeth Friedlander, John M. Kelley, M. Norma Sanchez, Efi Kokkotou, Joyce P. Singer, Magda Kowalczykowski, Franklin G. Miller, Irving Kirsch, and Anthony J. Lembo. “Placebos without Deception: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Irritable Bowel Syndrome.” PLoS One 5.12 (2010): E15591. Print.

• Lockton, Dan. “Placebo Buttons, False Affordances and Habit-forming.” Design with Intent. WordPress, 10 Jan. 2008. Web. Sept. 2012.

• Luo, Michael. “For Exercise in New York Futility, Push Button.” NYTimes. The New York Times Company, 27 Feb. 2004. Web. Sept. 2012.

• Murdoch, Jason. “Superstitious Athletes.” CBC Sports. CBC, 10 May 2005. Web. Sept. 2012. “Power Balance Band Is Placebo, Say Experts.” BBC News Wales. BBC, 22 Nov. 2010. Web. Sept. 2012.

• “Power Balance Endorsers, Athletes Who Wear Power Balance Bands.” Athlete Promotions. Web. Sept. 2012.

• Sandberg, Jared. “Employees Only Think They Control Thermostat.” WSJ. Dow Jones & Company, Inc., 15 Jan. 2003. Web. Sept. 2012.

• Stech, Katy. “Power Balance Sold to Chinese Manufacturer.” WSJ Blogs Bankruptcy Beat. Dow Jones & Company, Inc., 11 Jan. 2012. Web. Sept. 2012.

• Tritrakarn, Thara, Jariya Lertakyamanee, Pisamorn Koompong, Suchai Soontrapa, Pradit Somprakit, Anupan Tantiwong, and Sunee Jittapapai.”Both EMLA and Placebo Cream Reduced Pain during Extracorporeal Piezoelectric Shock Wave Lithotripsy with the Piezolith 2300.” Anesthesiology 92.4 (2000): 1049-054. Print.

• “Wade Boggs.” Baseball Library. Ed. Richard Lally. The Idea Logical Company, Inc. Web. Sept. 2012.

September 30, 2014

YANSS Podcast 033 – The psychology of forming, keeping, and sometimes changing our beliefs

The Topic: Belief

The Guests: Will Storr, Margaret Maitland, and Jim Alcock

The Episode: Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

Put your right hand on your head. Unless you are near a mirror, you can no longer see your hand, but you know where it is, right? You know what position it is in. You know how far away it is from most of the other things around you. I’m using the word “know,” but that’s just for convenience, because you don’t actually know those things. That is, you can’t be 100 percent certain your hand is on your head. You assume it is, and that’s as good as it is going to get – a best guess. We’ll come back to that. You can put your hand down now.

I once interviewed the great neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran, and asked him about a condition known as anosognosia. This is the term for a disorder that causes the sufferer to deny another disorder. Blind people will sometimes believe they are not, for example. I asked him about this because I had learned that he once treated a patient with paralysis of one arm who denied that the arm was paralyzed even though she couldn’t move it when asked. She could no longer make an emotional connection to her arm. She denied that the arm was even a part of her. That biological connection, that feeling of ownership, was missing from her mind, and when asked whose arm it was she would say it was her mother’s or her brother’s. She said someone was playing a prank on her from under the table. Patients like this will explain away obvious things, but never seem to come out and say something like “it is my arm but I can’t feel ownership of it.” If she looked at her arm she could see the facts of the matter, but facts couldn’t alter her narrative. This is a form of anosognosia, and in these cases family and friends who are on one side of reality have a difficult time understanding how those on the other can continue to believe as they do. Inside the head of the sufferer, it’s not an easy thing to realize they are wrong. One of the defining features of anosognosia is that facts often don’t work on those who suffer under its terrible spell. I asked Ramachandran how that could that be possible.

Ramachandran said I should imagine a general on a battlefield, about to give the command to attack when an advisor approaches. The advisor tells the general that one of their scouts now says the enemy is stronger than initially believed, and that the attack should be postponed. The general decides that the chance of this one scout being right isn’t worth the cost of delaying the attack, and decides to ignore him. Ramachandran then said to imagine that the scout instead says he saw that the enemy had nuclear weapons, and believes as soon as the battle starts the enemy will launch them. Now, in this scenario, the general decides it would be a bad idea to continue, and decides to believe the scout. In a typical brain, he said, the general is careful not to overreact to reports coming in from the field; many of your strange psychological mechanisms serve to keep you on-task in this way, phenomena like denial and rationalization. But if a report is serious and reliable, the general puts all that aside, suppresses it, and responds appropriately. Except in some people the general inside their heads doesn’t do that. Damage to the right parietal seems to make it so the brain can’t properly gauge when a situation has become too serious to depend on rationalization and denial. Those sorts of brains keep on confabulating, and that’s why people who are blind can somehow continue to believe they are not despite what seems like irrefutable evidence to those of us on the outside of their skulls. That’s how come a person can deny her arm belongs to her even though it is physically attached at the shoulder.

V.S. Ramachandran also writes about treating patients who have lost limbs, often an arm, but the maps of their bodies do not get updated after the loss. The brain continues to generate a virtual arm, a representation that was once grafted onto flesh. That’s what you felt when you put your hand on your head. That’s the difficult truth to accept, that there never was a real arm in the first place, at least, not in the brain…it was always virtual, it was always a model, the only difference with those who have lost a limb is that the model represents something that no longer exists, and it can’t be updated. The sensory organs that used to provide the information that updated the model have been lost, yet the model remains.

To borrow from Ramachandran’s battlefield, the agencies of your mind are kind of like a general surrounded by lieutenants, all receiving news of the world by messengers, but the whole group is trapped in a war room and only able to interact with a map of the battlefield populated by models of tanks and little toy soldiers. That’s what it is like to be a brain. You are trapped in a skull, unable to actually interact with the world outside. You depend on messages from sense organs written in code. When you decode the messages, you alter the map and the models, but that’s all you can ever hope to know about the outside world – that map and those models. The evidence gathered so far suggests that one of the most important discoveries in neuroscience and psychology is that you often mistake your interactions with the world to be direct and intimate, and your sensations to be perfect replicas of the elements of the world that your senses perceive. In other words, you sometimes believe that the map in your war room isn’t a map at all, that it doesn’t represent anything outside of itself, but that it actually IS the real world.

Once you understand that the brain generates a model that is a representation of a more complex and nuanced reality, you can see that your interactions are broad and blunt, approximate and presumptuous, and probably wrong in many ways but in the end, good enough. That’s as much as neuroscience is willing to give you – good enough. Your narratives and strategies and memories and actions and decisions and judgments, they are good enough.

All you can ever know about your own body, or the world outside of it, is what your brain tells you, and your brain doesn’t tell you the truth. It just makes an approximation, it makes a model of the world. This is where belief begins. If you drill all the way down. If you dig until you reach the rock, your original faith, your central belief, is in your model of reality, the one generated by your brain. That is your terminal dogma: your faith in your internal representations of the world around you. It isn’t limited to ownership of your limbs or the belief that your hand is on your head when you place it there. Who is right, you ask, when your messengers arrive, the people telling you vaccines are harmful or those telling you that they are harmless? Who is right, the climate scientists or the politicians who distrust them? Locked in the skull, its only interaction with the world based on models and maps, your brain can only make best guesses that are good enough.

Our guest for this episode, Will Storr, wrote a book called The Unpersuadables. In that book, Storr spends time with Holocaust deniers, young Earth creationists, people who believe they’ve lived past lives as famous figures, people who believe they’ve been abducted by aliens, people who stake their lives on the power of homeopathy, and many more – people who believe things that most of us do not. Storr explains in the book that after spending so much time with these people it started to become clear to him that it all goes back to that model of reality we all are forced to generate and then interact with. We are all forced to believe what that model tells us, and it is no different for people who are convinced that dinosaurs and human beings used to live together, or that you can be cured of an illness by an incantation delivered over the telephone. For some people, that lines up with their models of reality in a way that’s good enough. It’s a best guess.

Our guest for this episode, Will Storr, wrote a book called The Unpersuadables. In that book, Storr spends time with Holocaust deniers, young Earth creationists, people who believe they’ve lived past lives as famous figures, people who believe they’ve been abducted by aliens, people who stake their lives on the power of homeopathy, and many more – people who believe things that most of us do not. Storr explains in the book that after spending so much time with these people it started to become clear to him that it all goes back to that model of reality we all are forced to generate and then interact with. We are all forced to believe what that model tells us, and it is no different for people who are convinced that dinosaurs and human beings used to live together, or that you can be cured of an illness by an incantation delivered over the telephone. For some people, that lines up with their models of reality in a way that’s good enough. It’s a best guess.

Storr proposes you try this thought experiment. First, answer this question: Are you right about everything you believe? Now, if you are like most people, the answer is no. Of course not. As he says, that would mean you are a godlike and perfect human being. You’ve been wrong enough times to know it can’t be true. You are wrong about some things, maybe many things. That leads to a second question – what are you are wrong about? Storr says when he asked himself this second question, he started listing all the things he believed and checked them off one at a time as being true, he couldn’t think of anything about which he was wrong.

Storr says once you realize how difficult it is to identify your own incorrect beliefs you can better empathize with people on the fringe, because they are stuck in the same predicament. They are just as trapped in their own war rooms, most of the time unaware that the map they use is, as psychologist Daniel Gilbert once said, a representation and not a replica. They are judging the evidence presented to them based on a model of reality, a map that they’ve used their entire lives, and you can’t just tell someone that his or her map is of a fantasy realm that doesn’t exist and expect them to respond positively. You can’t just ask a person like that to throw away that map and start over, especially if they’ve yet to realize it is just a map, and their beliefs are only models.

In this episode we ask experts where do our beliefs come from, how do we know where we should place our doubt, and why don’t facts seem to work on people? We explore the psychology of belief through interviews with Margaret Maitland, an Egyptologist, who settles once and for all whether or not aliens built the pyramids. We also speak with Jim Alcock, a psychologist who studies belief itself who explains how emotions and rationality combine to form our concepts of reality.

In this episode we ask experts where do our beliefs come from, how do we know where we should place our doubt, and why don’t facts seem to work on people? We explore the psychology of belief through interviews with Margaret Maitland, an Egyptologist, who settles once and for all whether or not aliens built the pyramids. We also speak with Jim Alcock, a psychologist who studies belief itself who explains how emotions and rationality combine to form our concepts of reality.

In every episode, before I read a bit of self delusion news, I taste a cookie baked from a recipe sent in by a listener/reader. That listener/reader wins a signed copy of my new book, “You Are Now Less Dumb,” and I post the recipe on the YANSS Pinterest page. This episode’s winner is Heather Clarkson who submitted a recipe for Strawberry Cheesecake Sandwich Cookies. Send your own recipes to david {at} youarenotsosmart.com.

NOTE: I originally wrote about some of this, specifically the Ramachandran interview, in my second book, You Are Now Less Dumb.

Links and Sources

Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

My Interview with Ramachandran

September 15, 2014

YANSS Podcast 032 – Seeing willpower as powered by a battery that must be recharged

The Topic: Ego Depletion

The Episode: Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

Stains the dog abstains from cupcakes on “It’s Me or The Dog” on Animal Planet

One of my favorite tropes in fiction is the idea of the perfect thinker – the person who has shed all the baggage of being an emotional human being and could enjoy the freedom and glory of pure logic, if only he or she could feel joy.

Spock, Data, Seven of Nine, Sherlock Holmes, Mordin Solus, Austin James, The T-1000 – there are so many variations of the idea. In each fictional world, these beings accomplish amazing feats thanks to possessing cold reason devoid of all those squishy feelings. Not being very good at telling jokes or hanging out at parties are among their only weaknesses.

It’s a nice fantasy, to imagine without emotions one could become super-rational and thus achieve things other people could not. It suggests that we often see emotion as a weakness, that many people wish they could be more Spockish. But the work of neuroscientists like Antonio Damasio suggests that such a thing would be a nightmare. In his book, “Decarte’s Error” he describes patients who, because of an accident or a disorder, are no longer able to feel silly or annoyed or hateful or anything else. If they can, those feelings just graze them, never taking hold. Damasio explains that these patients, emotionally barren, are rendered powerless to choose a path in life. They can’t ascribe value to anything. Their world is flat. Despite remaining very intelligent and able to carry on conversations, they no longer make good decisions. Former business owners will lose all their money on bad investments. People who used to work from home will become lost in constantly reorganizing their shelves. Not only are their decisions flawed, but reaching conclusions becomes an excruciating process. When Damasio handed one of these patients two pens, one red and one blue, and asked him to fill out a questionnaire, the man was lost. To choose red over blue using logic alone took about half an hour. Every pro and con was listed, every branching possibility of future outcomes considered. Damasio wrote that “when emotion is entirely left out of the reasoning picture, as happens in certain neurological conditions, reason turns out to be even more flawed than when emotion plays bad tricks on our decisions.” Judgments and decisions corrupted by bias and passion are the only way we ever get anything done.

Choosing a blue pen instead of a red pen takes most people only a moment because the decision is driven by emotion alone. Try it now. Ask yourself which color ink you would prefer to use for the rest of this year. Why did you pick that color? The research suggests you feel your answer first, before you even know you’ve chosen, and then begin the work of rationally explaining yourself to yourself.

Psychology over the last 40 years or so has developed a model of the human mind in which our older and mostly unconscious system of emotions and hunches stands apart from our newer and mostly conscious system of rational, deliberate contemplation. Daniel Kahneman calls them system one and system two, fast and slow. Jonathan Haidt calls them the elephant and rider, and sometimes the master and the servant. Walter Mischel calls the interplay of these two complexes the hot/cool system. Every psychologist who supports the model has a favorite way of describing the two major branches of our minds – intuition and reason.

Not only have psychologists reframed how we see the collaboration of reason and intuition, but they’ve learned that the part of us that deliberates and contemplates, the part of us that Freud would have called the ego, can become exhausted. There is a body of evidence that reveals the conscious and rational system – the slow one, the rider of the elephant – gets tired very easily and eventually goes passive. Every deliberate act seems to weaken the ability to perform another. Eventually, you begin to give up earlier, to rush to conclusions sooner, and to eat things that you shouldn’t. You watch movies on cable that you already own, censored and full of commercials, even though you could watch your own copy with minimal effort. You do things that seem very un-Spock-like.

If you think of these two systems as id and ego, the work of psychologist Roy Baumeister suggests that the ego sort of runs on an internal battery, one that can be drained after heavy use, but recharges after rest and reward. If you don’t recharge it, you will find it difficult to keep your hand out of the cookie jar. He says that all sorts of things can lead to ego depletion, a state of mind in which your ego leaves its post and takes a nap, allowing the id and its emotions to take over. Depleted, you have poor willpower, self-control, volition, prosocial behavior, etc. Judges will even be less likely to grant parole until they’ve taken a break and eaten a sandwich.

In this episode we explore ego depletion and all the things that can cause it from feeling rejection to holding back tears to avoiding the temptation of cookies. Speaking of cookies…we also explore in this episode how psychologists have used cookies in novel ways to uncover the secrets of our minds. We examine the importance of cookies in psychological research from the work of Mischel to recent experiments that can cause normal people to steal confections and munch them like Cookie Monster in front of strangers.

In every episode, before I read a bit of self delusion news, I taste a cookie baked from a recipe sent in by a listener/reader. That listener/reader wins a signed copy of my new book, “You Are Now Less Dumb,” and I post the recipe on the YANSS Pinterest page. This episode’s winner is Jenne Bergstrom who submitted a recipe for Meyrick Cookies. Send your own recipes to david {at} youarenotsosmart.com.

LINKS

Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

SOURCES

Banja, John D. Medical Errors and Medical Narcissism. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett, 2004. Print.

Baumeister, Roy, and John Tierney. “The Authors of Willpower Answer Your Questions.” Interview. Freakonomics. Freakonomics, LLC., 22 Sept. 2011. Web. Apr. 2012.

Baumeister, Roy F., and John Tierney. Willpower: Rediscovering the Greatest Human Strength. New York: Penguin, 2011. Print.

Baumeister, Roy F., C. Nathan DeWall, Natalie J. Ciarocco, and Jean M. Twenge. “Social Exclusion Impairs Self-Regulation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 88.4 (2005): 589-604. Print.

Baumeister, Roy F., Ellen Bratslavsky, Mark Muraven, and Dianne M. Tice. “Ego Depletion: Is the Active Self a Limited Resource?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74.5 (1998): 1252-265. Print.

Carey, Benedict. “Analyze These.” NY Times. The New York Times Company, 25 Apr. 2006. Web. Apr. 2012.

Danziger, Shai, Jonathan Levav, and Liora Avnaim-Pesso. “Extraneous Factors in Judicial Decisions.” Ed. Daniel Kahneman. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108.17 (2011): 6889-892. Print.

Damasio, Antonio R. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. New York: Putnam, 1994. Print.

Floyd, Barbara. From Quackery to Bacteriology: The Emergence of Modern Medicine in 19th Century America. The University of Toledo, Feb. 1995. Web. Apr. 2012.

Gailliot, Matthew T., Roy F. Baumeister, C. Nathan DeWall, Jon K. Maner, E. Ashby Plant, Dianne M. Tice, Lauren E. Brewer, and Brandon J. Schmeichel. “Self-control Relies on Glucose as a Limited Energy Source: Willpower Is More than a Metaphor.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92.2 (2007): 325-36. Print.

Goodall, J. “Social Rejection, Exclusion, and Shunning among the Gombe Chimpanzees.” Ethology and Sociobiology 7.3-4 (1986): 227-36. Print.

Gorlick, Adam. “Need a Study Break to Refresh? Maybe Not, Say Stanford Researchers.” Stanford News Service. Stanford University, 14 Oct. 2010. Web. Apr. 2012.

Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon, 2012. Print.

Hagger, Martin S., Chantelle Wood, Chris Stiff, and Nikos L. D. Chatzisarantis. “Ego Depletion and the Strength Model of Self-control: A Meta-analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 136.4 (2010): 495-525. Print.

Holmes, Oliver Wendell. Medical Essays, 1842-1882. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and, 1891. Print.

Job, V., C. S. Dweck, and G. M. Walton. “Ego Depletion–Is It All in Your Head?: Implicit Theories About Willpower Affect Self-Regulation.” Psychological Science 21.11 (2010): 1686-693. Print.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011. Print.

Leher, Jonah. “The Willpower Trick.” Wired Science. Condé Nast, 09 Jan. 2012. Web. Apr. 2012.

Medical Class of 1889. University of Pennsylvania University Archives and Records Center. Web. Apr. 2012. http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/1800s/1889med/med1889entry.html.

Muraven, Mark, and Owen Flanagan. Lecture. The Mechanisms of Self-Control: Lessons from Addiction. The Oxford Centre for Neuroethics, University of Oxford. 13 May 2010. The Science Network. 13 May 2010. Web. Apr. 2012.

Muraven, Mark, and Roy F. Baumeister. “Self-regulation and Depletion of Limited Resources: Does Self-control Resemble a Muscle?” Psychological Bulletin 126.2 (2000): 247-59. Print.

Muraven, Mark, Dianne M. Tice, and Roy F. Baumeister. “Self-control as a Limited Resource: Regulatory Depletion Patterns.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 74.3 (1998): 774-89. Print.

Metcalfe, J., & Mischel, W. (n.d.). A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review, 3-19.

“Overview: Medicine 1800-1899.” BookRags. Web. Apr. 2012. http://www.bookrags.com/research/overview-medicine-1800-1899-scit-051234.

Tice, Dianne M., Roy F. Baumeister, Dikla Shmueli, and Mark Muraven. “Restoring the Self: Positive Affect Helps Improve Self-regulation following Ego Depletion.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43.3 (2007): 379-84. Print.

Tierney, John. “Do You Suffer From Decision Fatigue?” NY Times. The New York Times Company, 21 Aug. 2011. Web. Apr. 2012. A version of this article appeared in print on August 21, 2011, on page MM33 of the Sunday Magazine with the headline: “To Choose is to Lose.”

TV Tropes. The Spock. http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php...

Vohs, Kathleen D., Brian D. Glass,, W. Todd Maddox, and Arthur B. Markman. “Ego Depletion Is Not Just Fatigue : Evidence From a Total Sleep Deprivation Experiment.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 2.2 (2011): 166-73. Print.

Wegner, Daniel M., David J. Schneider, Samuel R. Carter, and Teri L. White. “Paradoxical Effects of Thought Suppression.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53.1 (1987): 5-13. Print.

Wootton, David. Bad Medicine: Doctors Doing Harm since Hippocrates. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006. Print.

Wrangham, Richard W. Chimpanzee Cultures. Cambridge, MA: Published by Harvard UP in Cooperation with the Chicago Academy of Sciences, 1996. Print.

August 28, 2014

YANSS Podcast 031 – Why do you sabotage yourself when trying to break bad habits?

The Topic: Extinction Bursts

The Episode: Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

Source: Corie Howell

Why do you so often fail at removing bad habits from your life?

You try to diet, to exercise, to stop smoking, to stop staying up until 2 a.m. stuck in a hamster wheel of internet diversions, and right when you seem to be doing well, right when it seems like your bad habit is dead, you lose control. It seems all to easy for one transgression, one tiny cheating bite of pizza or puff of smoke, and then it’s all over. You binge, calm down, and the habit returns, reanimated and stronger than ever.

You ask yourself, how is it possible I can be so good at so many things, so clever in so many ways, and still fail at outsmarting my own vice-ridden brain? The answer has to do with conditioning, classical like Pavlov and operant like Skinner, and a psychological phenomenon that’s waiting in the future for every person who tries to twist shut the spigot of reward and pleasure – the extinction burst, and in this episode we explore how it works, why it happens, and how you can overcome it.

Links

Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

People Think Experiences Bring Happiness, Still Opt for Things

People do not accurately forecast the economic benefits of experiential purchases

The original article on extinction bursts

Sources

“Three Dogs and Two Babies: So You’re Having a Baby…is Your Dog Prepared? – Canine University.” Three Dogs and Two Babies: So You’re Having a Baby…is Your Dog Prepared? – Canine University. Canine University. Web. 26 July 2010. (http://bit.ly/VPXA8T)

“Behavior: Skinner’s Utopia: Panacea, or Path to Hell?” Time. Time Inc., 20 Sept. 1971. Web. 26 July 2010.

Biederman, Jim. “Conditioning Examples with Answers.” Conditioning Examples with Answers. Anoka-Ramsey Community College. Web. 26 July 2010. (http://bit.ly/VPXe1O)

“Classical Conditioning.” Classical Conditioning. Changing Minds. Web. 26 July 2010. (http://bit.ly/VPXa2n)

“Extinction.” Extinction. Changing Minds. Web. 26 July 2010. (http://bit.ly/VPWVEg)

“Operant Conditioning.” Operant Conditioning. Changing Minds. Web. 26 July 2010. (http://bit.ly/VPX22D)

Operant Conditioning. YouTube. Web. 26 Aug. 2010. (http://bit.ly/YWId0p)

“Operant Conditioning Chamber.” Operant Conditioning Chamber. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 26 July. 2010. (http://bit.ly/YWJ0i6)

Webb, Matt. “Interconnected.” Two Kinds of Training ( 3 Jul., 2008). Interconnected. Web. 26 Aug. 2014. (http://bit.ly/YWJ3dK)

August 14, 2014

YANSS Podcast 030 – How practice changes the brain and exceptions to the 10,000 hour rule with David Epstein

The Topic: Practice

The Guest: David Epstein

The Episode: Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

Photo by Glenda S. Lynchard – Source: http://bit.ly/1rmH627

You live in the past.

You don’t know this because your brain lies to you and then covers up the lies, which is a good thing. If your brain didn’t fudge reality, you wouldn’t be able to hit a baseball, drive a car, or even carry on a conversation.

You may have already noticed this through its absence. Sounds that come from very far away don’t get edited. Maybe you’ve been high in the bleachers at a sporting event and saw the crack of a bat or the crunch of a tackle, but the sound seemed to arrive in your head just a tiny bit later than when it should have. Sometimes there is a delay, like reality is out of sync. You can see this in videos too. If you see a big explosion or a gun shot from far away, the sound will arrive after the camera has already recorded the images so that there is gap between seeing the boom and hearing it.

The reason this occurs, of course, is because sound waves travel much more slowly than light waves. But if that’s true, why isn’t there always a lag between seeing and hearing? How come you can carry on a conversation with someone at the end of a long hallway even though the light that’s allowing you to see her mouth is arriving well before the sound of her voice?

You can talk to people across a distance because your brain holds on to light info, waits for the sound info to arrive, edits them so that they line up, and then it releases the combined information to your consciousness. But that all takes time, and that’s why sometimes you catch the brain in a lie.

It takes about 80 milliseconds for the brain to generate consciousness, to take all the information flowing in and construct a model of reality from moment to moment. You interact with that 80-millisecond-old model, the afterglow. Everything you think is happening now already happened 80 milliseconds ago, and you are just now becoming aware of it over and over again. Sounds that occur more than 30 meters away take longer than 80 milliseconds to get to your ears, and so those sounds don’t arrive in time to get stitched together with the visual information. It’s called the 80-millisecond rule. That’s why you usually see the lightning well before you hear the thunder. You live in the center of a sphere about 60 meters in diameter. In the center, sounds and sights line up perfectly. Anything farther out does not. It’s also why you can snap your fingers and it seems like the sound waves are moving at the same speed as the light waves. They aren’t. It’s a lie, a representation of reality that’s more useful than the truth.

Since you live in the past, it should be impossible to do things like hit a baseball or duck a punch, yet athletes do these sorts of things all the time. As our guest David Epstein explains in the latest YANSS Podcast, professional baseball players and boxers don’t have faster reaction times than the average human being. No human being can make the circuit from eyes to brain to muscles fast enough to hit a ball in midflight or avoid an oncoming fist. You can’t change those natural limits with any amount of practice. So how do they do it?

Epstein explain that practice strengthens intuition, not reaction times. Even among chess players, practice builds up a cognitive database that nonconsciously informs our decisions and reactions. Experience and mastery are demonstrations of a robust, well-trained unconscious mind that senses tiny cues in the environment and then prepares an action that will occur later, syncing up reality the way you stitch together sounds and sights. All sports are a display of brains predicting the future based on intuition built up by practice – brains compensating for lag by seeing what is happening now, before the ball is thrown, before the punch is launched, and making a best guess on what will happen later. We also talk about the 10,000-hour-rule, nature vs. nurture, and how come the best athletes seem to come from the smallest towns.

Epstein explain that practice strengthens intuition, not reaction times. Even among chess players, practice builds up a cognitive database that nonconsciously informs our decisions and reactions. Experience and mastery are demonstrations of a robust, well-trained unconscious mind that senses tiny cues in the environment and then prepares an action that will occur later, syncing up reality the way you stitch together sounds and sights. All sports are a display of brains predicting the future based on intuition built up by practice – brains compensating for lag by seeing what is happening now, before the ball is thrown, before the punch is launched, and making a best guess on what will happen later. We also talk about the 10,000-hour-rule, nature vs. nurture, and how come the best athletes seem to come from the smallest towns.

After the interview, I discuss a news story about the psychology behind trying to get children to eat their vegetables.

In every episode, before I read a bit of self delusion news, I taste a cookie baked from a recipe sent in by a listener/reader. That listener/reader wins a signed copy of my new book, “You Are Now Less Dumb,” and I post the recipe on the YANSS Pinterest page. This episode’s winner is Chris Leslie who submitted a recipe for macaroon kisses. Send your own recipes to david {at} youarenotsosmart.com.

Links and Sources

Download – iTunes – Stitcher – RSS – Soundcloud

August 5, 2014

You Are Now Less Dumb now out in paperback!

Here are just a few of the hundreds of new ideas you’ll stuff in your head while reading You Are Now Less Dumb:

Here are just a few of the hundreds of new ideas you’ll stuff in your head while reading You Are Now Less Dumb:

* You’ll learn about a scientist’s bizarre experiment that tested what would happen if multiple messiahs lived together for several years and how you can use what he learned to debunk your own delusions.

* You’ll see how Bill Clinton, Gerard Butler, and Robert DeNiro are all equally ignorant in one very silly way that you can easily avoid.

*You’ll learn why the same person’s accent can be irritating in some situations and charming in others and how that relates to poor hiring choices as well as avoidable mistakes in education.

*You’ll finally understand why people wait in line to walk into unlocked rooms and how that same behavior slows progress and social change.

*You’ll learn why people who die and come back tend to return with similar stories, and you’ll see how the explanation can help you avoid arguments on the internet. You’ll discover the connection between salads, football, and consciousness.

LINKS TO BUY

Amazon - IB – B&N – BAM – Powell’s – iTunes – Audible – Google

EXCERPTS

An excerpt at Boing Boing from a chapter about: Pluralistic Ignorance

An excerpt at Big Think from a chapter about: The Common Belief Fallacy

Several nice excerpts at Brainpickings concerning: Self-Enchancement Bias

A video at PBS Digital Studios all about: Blowing Into Nintendo Games

Some tidbits at The Huffington Post: 7 Ways You Are Not So Smart

TRAILERS

THE STORY BEHIND THE GOOSE TREES

Before I explain where the idea came from, I’d like to endorse the people who did the hardest work. If you need a video, please contact Plus3. They made the trailers above, and they are great to work with. You can visit their website at http://www.plus3video.com.

It’s true. People educated and not so educated believed that geese grew on trees for at least 700 years.

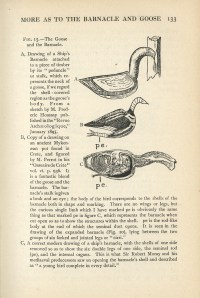

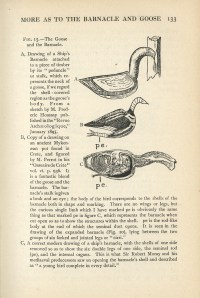

A certain type of barnacle often found floating on driftwood was thought to be a goose egg case because it kind of, sort of, looked like a goose that lived in the same area. According to the naturalist Sir Ray Lankester, nature texts going back to the 1100s described trees with odd fruits from which geese would hatch, and there is evidence to suggest the belief goes back 2,000 years earlier.

Images from goose transformations from Diversions of a Naturalist by Sir Ray Lankester

There was a particular breed of goose that lived along the marshes in Britain, and this goose migrated to breed and lay its eggs. The geese seemed to sometimes suddenly appear in large numbers in the same places where, while the geese were missing for long stretches, the barnacles tended to wash ashore. Wise, learned monks explained to the people of the day that the barnacles were the geese in their early stages of development. Lankester wrote that the belief was further solidified by those same monks who also claimed you could eat a barnacle goose during Lent because, well, it wasn’t a bird. Apparently the belief was well-established and quite popular because in 1215 Pope Innocent III announced that, although everyone knew they grew on trees, the eating of barnacle geese was still strictly prohibited by the church, effectively closing the loophole created by those wily monks.

“They do not breed and lay eggs like other birds; nor do they ever hatch any eggs nor build nests anywhere. Hence clergymen in some parts of Ireland do not scruple to dine off these birds at the time of fasting, because they arre not flesh nor born of flesh!” – Gerald of Wales, medieval historian, writing as royal clerk to Henry II in Topographia Hibernica

The idea wasn’t difficult to accept to minds of that era because spontaneous generation was already an accepted truth yet to be torn apart by scientists using scientific methods. People still believed that rotting meat gave birth to flies all by itself and that piles of dirty rags could transform into mice and that most everything else came from slime or mud. A tree that sprouted bird buds seemed reasonable, especially if after 500 years you had never once caught two of the adults mating.

Sometime in the 1600s the myth began to fade because explorers in Greenland discovered the birds’ nesting sites. The second blow came when people finally started poking around inside the weird buds. Lankester writes in his 1915 book, Diversions of a Naturalist, “The belief in the story seems to have died out at the beginning of the seventeenth century when the structure of the barnacle lying within its shell was examined without prejudice, and it was seen to have only the most remote resemblance to a bird.”

You don’t believe in goose trees today not because it’s a silly idea, but because scientists discovered evidence to the contrary and then passed that information around. The lesson here is that silly ideas don’t just go away because they are silly. You need a system to test them.

Science can be difficult to define without explaining a lot of explanations of explanations, but physicist Sean Carroll recently wrote on his blog that science can pretty much be boiled down to three principles (the following is a direct quote):

“Think of every possible way the world could be. Label each way an ‘hypothesis.'”

“Look at how the world actually is. Call what you see ‘data’ (or ‘evidence’).”

“Where possible, choose the hypothesis that provides the best fit to the data.”

Think about how you might apply those same principles in your own life – shopping, eating bagels, discussing politics, choosing a career, and so on.

Remember, without an agreed-upon system for making sense of reality and a network of observers questioning each other’s data and methods, goose trees remained common knowledge for hundreds of years. Imagine what weird, untested things might be floating around in your aquarium of beliefs.

I write about this in You Are Now Less Dumb because you should understand that your natural way of understanding the world is no better than the people who used to believe geese grew on trees. Just like them, you’re pretty terrible at being skeptical. Just like them, you prefer to confirm your beliefs instead of disconfirming them. It’s just the way brains work. You are less dumb because you were born after science became an institution. People have done science for long enough to falsify a lot of old myths.

The scientific method is a tool human beings use to prevent themselves from doing what comes naturally. Without it, you prefer to explain what you observe in reverse: you start with a conclusion and use motivated reasoning to defend an assumption formed through the lens of confirmation bias while committing the post hoc fallacy as you argue for your an explanation couched in narrative supported by hindsight bias and a mixed bag of other self delusions.

Science forces you to see your conclusions as what they usually are – hypotheses. It then makes a zillion other hypotheses and starts smashing them all to pieces with data. Eventually, the hypotheses that survive are more likely than the ones that perish. It’s a method you should borrow. Try it sometime, and after you’ve subjected your own hypotheses to abuse notice how that forces you to draw new conclusions about this strange, beautiful, complicated experience of being a person.

Diversions of a Naturalist by Sir Ray Lankester

Sources:

Carroll, S. (2013) What is Science? http://www.preposterousuniverse.com – http://www.preposterousuniverse.com/b...

Hancock, A. (2012). Weird Myths About Gooseneck Barnacles. http://www.ucluelet.travel/ – http://www.ucluelet.travel/blog/weird-facts-about-gooseneck-barnacles

Heron-Allen, E. (1928). Barnacles in Nature and in Myth 1928.

White, B. (1945, July). Whale-Hunting, the Barnacle Goose, and the Date of the “Ancrene Riwle.” The Modern Language Review Vl. 40, No. 3

Wilkins, J. S. (2006). Tales of the barnacle goose. Evolving Thoughts. http://scienceblogs.com/evolvingthoughts/2006/08/15/tales-of-the-barnacle-goose/

You Are Now Less Dumb out in paperback today!

Here are just a few of the hundreds of new ideas you’ll stuff in your head while reading You Are Now Less Dumb: