Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 97

July 9, 2013

Army officer: I think I know why those departing Marine LTs wrote anonymously

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Jan. 7, 2013.

By Lt. Roxanne Bras, US Army

Best Defense office of JO issues

Speaking

authoritatively for a cohort is difficult and dangerous, but what's been said

in the two Marine JO's blog posts resonates with much of

what my peers say daily. That's not to

say that their ideas are correct; perhaps junior officers always feel

marginalized and hostile to the senior officer promotion system. But I'd

argue that the spirit of the posts is accurate, both as perceived by JOs and as

demonstrated by the military's HR system.

But

first, to the anonymity and its ensuing controversy, I'll bet that the Marines

didn't use their real names for precisely the same reason that I hesitated to

write this. Instead of engaging with an idea on its own merits, many

quickly look to the author to discredit him. Detractors love any evidence of

inexperience as an excuse to ignore the substance. The chorus of critics cry,

"He only served like 6 months. Never saw real combat." Or "he's

not infantry/isn't tabbed." Or "he's such a self-promoter and only

wrote that for attention." The ideas are forgotten and what remains is

slander. So why attach your name to something if it will only detract from the

argument? Until the military community becomes more idea and less

individual/ORB/ribbons focused, people will hesitate to participate in open

forums.

As to

the ideas, identifying the top 20 percent of JOs isn't easy. There are late

bloomers, people who are academically talented but are poor leaders, etc. But

just because talent identification is hard, doesn't mean the Army shouldn't

make incremental steps toward improving it

Just

one example: The first experience JO's have with Army promotions systems is

with the Order of Merit List, used to determine branch and first assignment.

The OML weights PT, academics, and military proficiency. It also sends a huge

message: academics is about checking the block. While GPA is weighted as

something like 40% of the OML, there are no adjustments for rigor of

institution or major. A 2.0 at MIT is the same as a 2.0 at any other school.

That only makes sense if the army thinks there is zero correlation between the

standing of the institution, or the relevance of the major to a specific

branch, and a JOs performance. And if that's the case, why care about GPA at

all? Just make the Army an institution that promotes PT and other metrics of

proficiency.

Improvements

don't have to be complicated. Many institutions and businesses identify,

incentivize, and promote talent. How to tailor these existing solutions to the

unique nature of the military? That would

be a conversation worth having.

And

even small improvements in the military's HR system would be significant to JOs

because they're symbolic. Instead of the mantra, "a degree's a

degree," something countless officers have told me, the Army could have the

mantra, "we are a profession and so value education." That doesn't

mean that we are a profession that gives extraordinary weight to eggheads, just

that we acknowledge that education, self-improvement, and rigor are real things

and might eventually impact the way an officer conducts a war.

Seeing

incompetents and careerists advance is frustrating, but is something I imagine

I'd see even if I left the military. But the inevitabilities of bureaucracies

shouldn't excuse the specificities of the military's talent retention

problems.

(For

what it is worth: I am not getting out, am not infantry, do not claim to be a

bad ass or an expert in anything, and am always interested in learning how to

better think about these issues.)

Roxanne

Bras is a 1LT in the U.S. Army, serving at Fort Bragg, NC. She is a graduate of

Harvard College and Oxford University. The views expressed here are her

own and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Army, the Department of

Defense, or the U.S. government.

July 8, 2013

We're getting out of the Marines because we wanted to be part of an elite force

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Jan. 4, 2013.

By "yet another Marine LT"

Best Defense department of the JO exodus

Why are

we getting out? It's about the low standards.

We

joined because we wanted to be part of an elite organization dedicated to doing

amazing things in defense of our nation. We wanted to make a contribution to

something great, to be able to look back at a decisive chapter in American

history and say "yeah, I was part of that." We joined the Corps because if we

were going in to the fight, we wanted to serve with the best. We wanted the

kind of job that would make our friends who took soulless, high-paying

corporate jobs feel pangs of jealousy because we went to work every day with a

purpose.

It

causes a deep, bitter pain to acknowledge that I don't think this is the

organization in which I currently serve. The reason we're getting out is

because the Marine Corps imposes a high degree of stress, yet accepts Mission

Failure so long as all the boxes on the list are checked.

I'm

talking about the Field Grade Intelligence Officer in Afghanistan who didn't

know who Mullah Omar was. I'm talking about a senior Staff NCO in the

intelligence community who could not produce a legible paragraph. I'm talking

about a Battalion Commander who took pride in the fact that he had done zero

research on Afghanistan, because it allowed him to approach his deployment with

"an open mind." I'm talking about contractors, some of whom were literally paid

ten-fold the salary of my junior Marines, who were incapable of performing

basic tasks and functionally illiterate. The problem is not so much that these

individuals pop up every now and then, as every organization has its bad eggs,

but rather that we see them passed on through the system, promoted and

rewarded. If we are truly the elite

organization we claim to be, how do we justify the fact that we allow these

individuals to retain positions of immense influence, much less promote through

the ranks? How do we justify this endemic tolerance for mediocrity or

outright incompetence?

If you

really want to know what an institution values, don't look at its mottos or

mission statements. Look at how it spends its resources, especially its human

capital. Economists call this "Revealed Preference." When I was in the midst of a time-critical

project aimed at mapping insurgent networks in Helmand, I was told to put the

project on hiatus so I could organize a visit from General Allen. The implicit

message was that a smooth itinerary and content General were more important

than catching an insurgent cell before they left for Pakistan. How else was I

supposed to interpret this? In my opinion, it's not so much that the Marine

Corps doesn't value ideas, but that -- when the chips are down and careers are

at stake -- it values appearance and conformity more than winning. The implicit

message -- what the Marine Corps reveals by its actions -- is that it's okay to

fail to provide any added value, so long as the PowerPoint slides are free of

typos, no serialized gear is lost, and everyone attends the Sexual Harassment

Prevention training

The

biggest issue is that few are willing to acknowledge Mission Failure because

doing so is considered "unprofessional," especially for a lieutenant. As an

Army Special Forces veteran I worked with was fond of saying, "you get what you

incentivize." As it currently stands, there is an overwhelming incentive for

officers at all levels to simply keep their units looking sharp, turn in rosy,

optimistic assessments, keep off the XO's radar and, above all else, keep from

rocking the boat. No matter what becomes of your battlespace, eventually the

deployment will end and you can go home. Why risk casualties, a tongue lashing

or missed PT time when the reward might not come for years down the road? Why

point out that the emperor has no clothes when everyone one involved is going

to get their Navy Comms and Bronze Stars if we just let him keep on walking

down the road.

We

should be better than this. I have found several of the comments and reviews of

your latest book baffling. We can quibble about the merits of Marshall's

management techniques or the specific metrics by which we should measure

officer performance. But can't we unanimously agree that sub-par commanders

should be weeded out, especially in an organization that calls itself "the

finest fighting force on the face of the earth?" The practice of actively

relieving (and eventually separating) leaders for under-performance is no

panacea, but shouldn't it at least be a starting point?

I don't

want to be misunderstood. The most

extraordinary and talented people I've ever met are still serving in the Corps.

I live in a wonderful area, I'm well-paid and generally like the people I work

with. Given the chance, I would happily deploy again. But looking down the road

at what the billet of a Field Grade officer entails, I have to wonder whether

the sacrifices will be worth it. Maybe they will. I've seen some Field Grade

officers who love their jobs and feel like they're serving a purpose. But I'm

not sure I'm willing to take the gamble.

I was told at The Basic School that the most

important role as a leader is to say, when everyone is tired and ready to

declare victory and just go home, "guys, this isn't good enough, we have to do

better." I simply don't see enough leaders willing to say, regarding the things

that really matter, "guys, the last

eleven years weren't good enough, the nation needs us to do better."

July 3, 2013

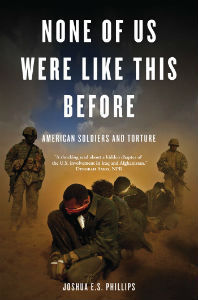

'None of Us Were Like This Before': Why hasn’t the U.S. military done a better job of addressing torture by our soldiers?

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on January 2, 2013.

That was the question that kept on coming back to me as I

read Joshua Phillips' None of Us Were Like

This Before. It is not a perfect book but it is an

important one.

Yes, there are ethical and moral reasons for conducting a

comprehensive review of instances of torture of Iraqis, Afghans and others by

American soldiers over the last 10 years.

But there also are practical reasons:

1. The damage torture does to those who inflict it. (Two of the

soldiers in the unit Phillips examines killed themselves after coming home.)

2. The damage torture does to our war efforts-both in the host

populations, and in world opinion.

3. The effect on the current force.

The questions I would like to see addressed include:

--Who tortured?

--Why?

--Who stopped torture?

--What were the characteristics of units that indulged in

torture? And of those that didn't?

--How can we better train soldiers to deal with this?

--Are there continuing effects on the force that need to be

addressed?

One final note: Phillips writes that, "I rarely met a

detainee who had received an apology, or any acknowledgement at all, for the

harsh treatment he had endured during U.S. captivity."

July 2, 2013

A Marine officer: I'm leaving the Corps because it doesn't much value ideas

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on December 14, 2012.

By Anonymous

Best Defense department of junior

officer retention

I'm

an infantry officer in the Marine Corps. I deployed last year to Helmand

Province on an embedded training team with the Afghan National Army. It was an

incredible experience, and I'm proud of what we accomplished together, but now

I'm in my last month of active duty and I'll be getting out as a first

lieutenant. I decided to leave the Marines a few months ago. (I was career

designated, which I say not to brag, but so you don't think I'm some

disgruntled jarhead.)

I've been closely following the discussion that you kicked off with your book,

your piece

in The Atlantic, and on Best

Defense. I want to weigh in on one point about which I feel strongly -- it

is that firing certain generals will send a message to junior officers about the

value of adaptability and critical thinking. I don't know that it will, but you

are absolutely correct that such a message is necessary.

The conclusions you fear people may draw regarding Petraeus's departure -- "critical

thinking and ideas are overrated" -- were

particularly poignant. I know you're talking Army. Sadly, it applies to the

Marine Corps, too.

An example: As the wars draw to a close, the Marine Corps is preaching a return

to its roots. This is all well and good. But it seems as if everyone is holding

up the 1990s as an idyllic time in the Marine Corps's history, as if the past

decade with all of its lessons and changes was an aberration. My fear is we

will learn very little from it.

In my battalion's after action report from the deployment, there are more than

fifty topics discussed. Just three of them relate to partnering, the main

effort in Helmand and our primary mission. The rest are tactical prescriptions

with a few operational suggestions thrown in -- not the sort of analysis you

want from a battalion staff.

If you've read Rajiv

Chandrasekaran's new book, you know how General Larry Nicholson is

portrayed. He isn't perfect, but he at least "gets it." My

impression, having endured dozens of empty speeches from generals these past

few years, is that men like him are few and far between. What concerns me much

more, though, is that among my peers, the ones with ideas are the ones getting

out, because they just don't feel the organization values them.

During the summer of 2011, the

author served in Helmand Province as a Tolai Advisor to the

Afghan National Army's 215th Corps. The views presented here are his

own.

July 1, 2013

What a good senior NCO does: Move around, keep an ear open, turn over rocks

During the summer, the Best Defense is carrying

re-runs of good items that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This one originally ran

on 6 December 2012.

One

of the things a good senior leader does is move around his or her unit. Don't

wait for bad news to come to you. Often, it won't be allowed to.

The

new issue of Army Times has a good

piece by Michelle Tan about a predatory drill sergeant who in one

10 day period earlier this year had various forms of sex with one female

recruit, oral sex with another, a groping and kissing session with a third, and

indecent language with some others.

The

first

woman to complain was a 20-year-old victim who found the

chain of command unresponsive. She went to one drill sergeant, who told her,

"You don't want to open that can of worms, Private. . . . That's my battle

buddy's career you're trying to fuck up." Her first sergeant didn't believe

her. The company commander said he would launch an inquiry, which, she said, led

nowhere, and wasn't reported to superiors. The woman said that other trainees

who had been assaulted were afraid to come forward, especially after they saw

how the drill sergeants ganged up on her and accused her of lacking integrity.

Then

she ran into the battalion command sergeant major as he was moving around the

unit. He listened to her, then called a meeting of all the females in the

company. It lasted about 90 minutes. "That's when the others came forward," the

woman said.

The

abusive drill sergeant, Luis Corral, has been found guilty. He was busted to

private, sentenced to five years in the brig, and will get a bad conduct

discharge when he gets out. Then he must register as a sex offender.

C U in September

As of today, Best

Defense is going into summer re-runs. I

may surface occasionally with news or guest columns that just can't wait for "when the summer's through."

Is terrorism getting boring? (II)

My friend, retired

Army Col. Bob Killebrew, in response to my question (above) of the other day, writes:

The answer is, it is

as 'terrorism' per se, but it's not

when you consider what it's becoming. Terrorism is becoming part, perhaps the

major part, of a mix of terrorism, crime and illicit states that will challenge the rule of law and

international order in the 21st century.

June 28, 2013

Did the regimental system optimize the British army for small wars? And what does that all mean for today's U.S. Army?

Those, little grasshoppers, are the two

questions that occurred to me as I read Max Hastings's comment (in Winston's War) that during World War II, "German,

American and Russian professional soldiers thought in divisions; the British

always thought of the regiment, the cherished ‘military family.' Until the end

of the war, the dead hand of centralized, top-down command methods, together

with lack of a fighting doctrine common to the entire army, hampered operations

in the field."

This was, Hastings goes on to write, one

reason that the Germans were better at everything from combined arms attacks to

mundane but essential tasks such as recovering disabled tanks and trucks from

the battlefield.

Yet that same small, cohesive structure

might have been good for fighting small wars, with units able to carry on

quietly for years without getting much attention, getting to know one area

well.

So: What, if anything, does this

suggest for how the U.S. Army should be organized for the future? (Or should the small war mission be sent back to the Marines?)

Fix the U.S. government by networking

By Julia L. Stern

Best Defense guest

columnist

People say government is broken, that no matter how many interagency

working groups or strategy documents are produced, the stovepipes that have

been long-entrenched among government offices will inevitably remain.

As an idealistic 20-something at the outset of my career in Washington,

I of course believed that my peers and I would break down the walls of

bureaucracy and effect change from the inside out. And while there was certainly

momentum to integrate efforts across agencies, particularly within the

intelligence community in the wake of 9/11, I now understand the reality of

implementing information sharing and integration ideas to be more nuanced than

adhering to the mandates of the 9/11 Commission Report. And while the

millennial generation -- increasingly populating the workforce -- is

characterized as über-connected networkers knowing no barriers, communication

and info sharing at all levels occurs based on personal relationships and is ad

hoc at best.

Retired general Stanley McChrystal recently sent me an e-mail sharing

his thoughts on the issue, from the perspective of a leader well-versed in

innovative organization:

The speed and complexity of how we operate now means that we need to be

able to operate across organizational lines earlier in careers, and at more

junior levels. That means you can't afford to have people toiling within their

respective ‘guilds' developing journeyman-like technical proficiency -- yet

largely not needing to understand or comfortably work across organizational

lines. Senior people had that responsibility.

Second, we've found that during the years of isolated service building

internally focused skills and experience, individuals tend to internalize

strong organizational cultures that encourage, reward, and sometimes even

prevent, working effectively with other agencies or organizations.

While institutional change takes a long time to stick, there are three

key steps we can take as a government to foster greater collaboration both at

the individual and at the institutional level:

1. Develop a U.S. government-wide interagency

academy.

Just as each of the military services has its own academy to train and

prepare future officers in the operating forces, there should be a comparable

opportunity for junior U.S. government personnel -- both military and civilian

-- to level the playing field of knowledge across all agencies and job

functions at the outset of their careers.

A program to teach young action officers about their counterparts across

Defense, State, USAID, Treasury, Congress, Justice, the intelligence community,

and law enforcement elements would raise awareness of capabilities and

authorities outside our own agencies, and of the value inherent in

collaborating with partners. Additionally, the curriculum should follow a

standardized USG planning process (and accompanying vocabulary) that can

actually be understood and implemented across agencies. Participants would end

up with the same understanding and interpretation of USG policy in the

classroom, and therefore be much better equipped to work together once on the

ground, whether in Washington or downrange in a combat zone.

2. Make available more interagency rotations

for junior personnel.

Given the integrated nature of future security operations, Defense

officials have acknowledged the need to increase engagement with other services

and civilian agencies such as the Department of State and USAID -- both from a

high-level policy planning perspective in Washington, as well as on the ground

within country teams and joint organizations.

A prime example of institutional efforts toward integration can be taken

from the Marine Corps's Junior Officer Strategic Intelligence Program. Junior

level officers are immersed in the work and culture of an intelligence agency

office, creating lasting professional connections and exposing them to data and

tools that they would have otherwise not known to exist -- resources that these

officers will take back with them to the Marine Corps. Similarly, the presence

of Marine officers in these civilian agencies serves as a constant reminder to

policymakers and policy informers of Marines in the field and how these

policies impact troops. Beyond the Marine Corps, the Department of Defense and

intelligence community offer similar joint duty and educational opportunities

for military and civilian personnel to gain exposure outside of their home

agency.

These types of cross-sector experiences are crucial as we face a set of

interconnected, complex global challenges that will require innovative

approaches and resources to address. The key is making these opportunities

known to personnel across military and civilian agencies early enough in their

careers, so that they can leverage the training, education, and other

prerequisites necessary to pursue the joint, interagency experiences that will

broaden their skills and strategic perspectives. The existing Presidential

Management Fellows program -- the mission of which is to foster a cadre of

future government leaders -- exemplifies this opportunity by exposing fellows

to several interagency rotations over two years. This model should be embraced

across government.

3. Ensure implementation of interagency

experiences throughout one's career, and tie

promotion and professional incentives to interagency rotations.

Experience from interagency rotations and exposure to counterparts at a U.S.

government academy, no matter how productive at the time, will be far less

worthwhile for the individuals and institutions involved if not directly

implemented throughout the participant's career.

It is often simply easier not

to reach out to another office and get another opinion on the issue at hand,

particularly when a deadline is fast approaching. This is human nature. There

must be a mechanism to ensure accountability at the institutional level.

Further, senior leaders across agencies and services must equally endorse

promotion of personnel with interagency experience, acknowledging not only the

value but the necessity of these experiences to bolster the future of the USG

workforce. Individual institutions have much to gain -- a better informed workforce

and the ability to influence partners -- from a program of earnest engagement

with the interagency, particularly if the resulting relationships and exchange

of best practices are infused back into U.S. government channels.

Since this legion of young professionals will inevitably assume the

ranks and decision-making responsibility of U.S. policymakers, we must start

the process of earnest collaboration now. This is not to say by any means that

GenY/millennials' networking instincts are right and our predecessors are

wrong. It all comes down to the individuals involved, and turf wars and

hoarding of information certainly exist throughout the ranks. We are not

necessarily more curious about our peers' perspectives than are our

supervisors, nor are we adequately incentivized to seek out counterparts on a

more-than-ad-hoc basis. But the technological and intellectual foundations of

borderless communication have been laid -- those entering the workforce in 2013

have never known a world where instantaneous virtual contact is not the norm --

and in a world where geographic and sectoral lines are increasingly blurring,

it has never been more critical (or possible) to actually embrace our networks.

Ultimately, institutions have to become networked and not just the

people inside them. However, by developing robust training, education, and

exchange opportunities for junior personnel -- and ensuring these experiences

are strategically managed throughout their careers -- the next generation of

our government will naturally mirror its people.

Julia

L. Stern is a senior consultant with Booz Allen

Hamilton, where she has worked on Afghanistan, national

security, and intelligence issues for the Department of Defense, as well as

security cooperation policy for the Marine Corps. She plans to pursue a master's

degree in public policy at the Kennedy School this autumn.

Gellman vs. Lewis on leaks vs. security

By Tsion Hiletework

Best Defense guest reporter

What was

most striking about a discussion of government surveillance programs at CSIS on

Tuesday was the width of the gap between cyber-experts focusing on national

security and journalists focusing on constitutional rights.

Bart

Gellman of the Washington

Post called for more media scrutiny of the "so-called spy programs." James Lewis, a CSIS cybersecurity expert, responded, rather

dismissively, "There aren't enough people in analysis to make investigating

your private sex life priority number one."

On the

other hand, Lewis recognized the need for more transparency, while Gellman

conceded that publicly admitting to PRISM is difficult for the

government because its contents often contain private databases and warrant-based

information.

What to

take away? Well, even with the questionable intent and conduct of what Lewis

called the "NSA's free backup service," Gellman also noted that the

program has been treated as constitutional by the three branches of the federal

government. In other words, the line between terrorism protection and individual intrusion remains hazy.

Gellman

and Lewis may have contrasting opinions, but despite their differing points of

origin, they sat down at the table to talk directly. Whether the government

will be as direct in discussing its clandestine

programs seems unlikely.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 437 followers