Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 95

August 2, 2013

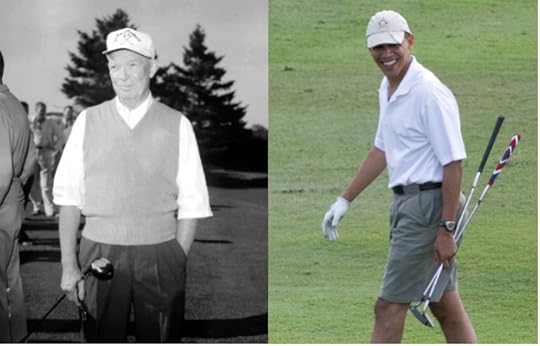

Ike and Obama: Is crisis avoidance the dominant foreign policy trait of both?

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Feb. 18, 2013.

I was in a

discussion the other day of the Obama administration's foreign policy. The more

I listened, the more President Obama began to remind me of President

Eisenhower.

There is indeed a

long list of foreign crises pending right now:

getting out of

Afghanistan

Syria

Iran/nukes

Af/Pak

Pakistan vs.

India

China vs. Japan

slow collapse

of North Korea

global warming

European

economic situation

advent of

cyber-warfare

But as I listened

to the discussion, I thought of President Eisenhower, who took office and set

to getting us out of the Korean War, as Obama did with Iraq. He also worked

hard to keep us out of the French war in Vietnam, overriding the Joint Chiefs'

desire to use nukes to help the French. He also rejected pleas of many to

intervene in the Hungarian Revolution. And he had the Suez Crisis, with the

French and British. Then there were issues of Stalin's successors in the Soviet

Union, which was rapidly building its nuclear arsenal.

I suspect that

Obama's dominant impulse is to keep us out of the problems he sees overseas,

just as Ike sought to keep us out of Vietnam and Hungary. Many people disagreed

with his decisions. But he was a successful president.

August 1, 2013

The many ways in which the French gov't is dead wrong to pay ransom for hostages

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Feb. 11, 2013.

Vicki

Huddleston, a former U.S. ambassador to Mali, says that the French government paid

$17 million to ransom French nationals in recent years. She further alleges

that these payments funded al Qaeda-linked operations in Africa.

The

French are wrong to do this. Not just mildly wrong, but massively wrong. Not

only are they funding terrorism, they are increasing the chances that their

people will be nabbed.

I say

this as someone who feared getting kidnapped in Baghdad. This was at a time

when Iraqi criminals supposedly were nabbing people and then selling them to al

Qaeda. I was once in a group of reporters summoned to the Green Zone for a

briefing from an American security official. He informed us that Baghdad was

the most dangerous city in the world, that we were the most lucrative targets

in the city, and that he thought we were nuts. Thanks fella!

Bottom

line: I felt that my best defense was the U.S. government policy of not paying

kidnappers. I still do.

July 31, 2013

Comment of the day: A father discusses the marker for his son in the backyard

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Feb. 8, 2013.

From "Gold Star Father":

The government marker (VA supplied) is (illegally) in my

backyard bolted to a flat stone that I found and it lies under a Weeping Willow

that friends of my wife gave to her. I make it a point to look at it nearly

daily, christen it with splatterings of whatever cocktail I may have in hand,

and have a conversation with my son. The marker is mine, its for me. My son's

ashes were returned to the sea. The marker is my place to go. It's illegal that

I have it, but I know/knew ways to make it happen to be in my possession. I

defy the VA cemetery police to come and get it. There will be blood if they

show up in my driveway.

July 30, 2013

Do we dishonor the dead with 'Operation Iraqi Freedom' on their tombstones?

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Feb. 7, 2013.

By Charles Krohn

Best Defense department of second

thoughts

Is it an honor or a cruel joke to read "Operation Iraqi

Freedom" on the headstone of a fallen soldier?

Given the irony of OIF in a historic

context, the question is

not irreverent, but it is relevant. This wouldn't be true, of course, if our

invasion had yielded results intended and predicted, however imperfectly.

As an old soldier who has carried

one too many body bags out of the battlefield, I feel a great kinship with the

next of kin of the fallen. Few memories hold greater pain.

I wouldn't even ask this

question if I didn't wonder if some in the Gold Star community weren't also

asking it, even to themselves. And if any read this, please accept my reverence

for you and the deceased. I know your loved one answered

the call of the nation, understanding great risk was necessary to protect

our country and help spread freedom among the oppressed. What could

be more noble?

Is it not just as honorable now to

recognize the prospect of freedom in Iraq as originally postulated is remote?

As others have written, there is still great confusion about who will lead

Iraq. The only thing most agree upon is that Iran, once held in check by Iraq,

is now spreading its virulent reach deeper into the region, with a nuclear

threat just around the corner.

Simply stated, the inspiration for

Operation Iraqi Freedom was a dream. Does it honor or dishonor those who fell

to perpetuate this myth on their headstones?

Should the matter be swept under the rug as an incidental

slip of history or should next-of-kin have the option of a new headstone,

marking sacrifice without promoting an idea whose time has passed?

Charles A. Krohn

is the author of

The Lost Battalion of Tet

. Now chilling in Panama City Beach, Florida,

he

served in Iraq in 2003-2004 as public affairs adviser to the

director of the Infrastructure Reconstruction Program, and later as public

affairs officer for the American Battle Monuments Commission.

July 29, 2013

Ten questions about the future of counterinsurgency and stabilization ops (I)

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Feb. 6, 2013.

By Major Tom Mcilwaine,

Queen's Royal Hussars

Best Defense guest columnist

There

appears to be a growing sense that the era of COIN that began on 9/11 is

drawing to a close. The chief prophets of the philosophy are, for various

reasons ranging from the personal to the professional, no longer quite the

force they once were, or are not needed quite as urgently by politicians who

have accepted the drawdown from Afghanistan as the end of the era of nation-building

through COIN. Nations are growing tired of seemingly endless wars that rumble

on, without a positive conclusion. There is a belief that we, the West, cannot

afford to fight these campaigns anymore, not in an age of austerity and fiscal

cliffs, which seems to be the one thing on which economic commenters and

treasury secretaries across the political spectrum and across the West can

agree. Perhaps more interestingly there is also a growing belief that we can

opt out of fighting such wars in the future. The trend in staff colleges around

the world is to return to the proper business of

soldiering

-- major combat operations. This trend is bolstered by a belief that our skills

in this area have atrophied over the last decade or so of constant patrolling

in the deserts, towns, and mountains of obscure foreign countries of which we

never really knew much about, or cared much for.

Notwithstanding

the wishes of senior commanders, who make much of the fact that the we in

Western militaries must not simply press the reset button and dump our

experiences of the last decade, it seems probable that the need to train for "old

school" major combat operations will probably lead to this happening in

practice -- because people train to be good at what they are going to be

assessed on, which in the near future is going to be old fashioned warfighting,

however it is currently described. And at the moment we lack experience in this

area. A personal example illustrates this. I will take command of a cavalry

squadron in September; I have not been employed on tanks since 2005 and the sum

total of my armored experience amounts to a little less than two months. If you

were my regimental commander, in a post-Afghan conflict world, would you be

more worried about training me to do my core skills -- armored warfare -- or

ensuring I retained more esoteric knowledge that is no longer in vogue -- COIN?

As

this belief grows stronger (and it will -- especially after 2014) there will be

a tendency to put away the lessons of the period of 2001-2014, in a part of our

brain that we do not choose to look at very often. And then, when in years to

come we find ourselves fighting another similar campaign in another part of the

world that we also know little of and care even less for, we will find

ourselves having to go through the same painful process of learning and

adaption that we have experienced over the last decade. At the risk of naming

the elephant in the room, we run the risk of repeating the mistakes of the

post-Vietnam era.

There

is an even more frightening prospect than this, however. What if we don't

actually learn the correct lessons at all from our experiences? What if, in the

hurry to put away the experiences of the last decade, we find ourselves failing

correctly to identify what it is we have been doing, and so when the time comes

to bring forth the knowledge so painfully earned, we bring forth the wrong

solution? Put bluntly -- will we actually learn any lessons at all, let alone

the correct ones, or will we simply repeat the platitudes of today in the

future, while ignoring the hard facts? If we avoid the Vietnam syndrome, will

we fall victim to the Northern Ireland syndrome?

This

is an urgent point that needs to be addressed. Now. Not when we next find

ourselves doing COIN. To try and ensure that this is not the case I have drawn

up a list of 10 questions which I believe it might prove profitable to answer,

or at least discuss. I have no particular answers in mind for them, because I

myself was a distinctly average COIN practitioner, full of zeal but lacking

tact and understanding. With these limitations in mind I present my questions

for better minds than mine to answer.

Question One -- Have we really been fighting counterinsurgency

campaigns at all? The simple answer to this question is, "Yes. That is what the

manual is called, idiot." But before the idea that we haven't been fighting

counterinsurgency campaigns at all is dismissed out of hand, consider the

following supplemental questions. Is it possible to fight expeditionary COIN? Can

you fight a COIN campaign when you first have to remove the legitimate

government of another country? Can you fight a COIN campaign when you are seeking

to radically alter the fundamental nature of a society? Or, taken together, do

these factors make you a better fit for the role of the insurgent (albeit one

so well-equipped with iPads and bottled water that we could pass for the Occupy

Movement) than counterinsurgent? This links back to the fundamental question

asked by Clausewitz -- what sort of war are you fighting? It is critical to

acknowledge that we are not likely to deploy deliberately to fight a COIN war; we

deploy to do something else -- e.g. foreign internal defense or regime change

-- and then our stabilization operation goes wrong and we are forced to fight a

COIN war. Being able to recognize this (the nature of the war we are fighting)

is the first step in being able to adapt and win.

Major Tom

Mcilwaine is a British Army officer who is currently a student at the

School of

Advanced Military Studies at Ft. Leavenworth. He has deployed to Iraq as

a platoon commander and battalion operations and intelligence officer,

to Bosnia

as aide to the commander of European forces and to Afghanistan as a

plans officer with I MEF (Fwd). The views here are his own and do not

necessarily

reflect those of the School of Advanced Military Studies, the U.S. Army,

the

U.S. Department of Defense, nor perhaps even those of

the

Sussex

County Cricket Club

.

July 26, 2013

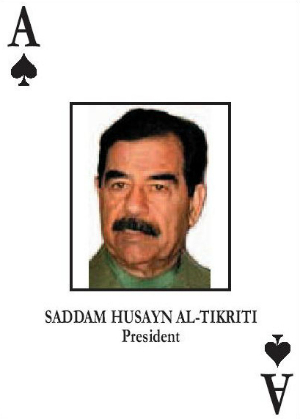

Question of the day: Was removing Saddam Hussein in fact a good thing?

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Feb. 5, 2013.

Recently I was at a foreign policy discussion in which a

participant said that everybody agrees that the removal of Saddam Hussein was a

good thing, despite everything else that went wrong with the boneheaded

invasion of Iraq.

I didn't question that assertion at the time, but found

myself mulling it. Recently I had a chance to have a beer

with Toby Dodge, one of the best strategic thinkers

about Iraq. He said something like this: Well, you used to have an oppressive

dictator who at least was a bulwark against Iranian power expanding westward.

Now you have an increasingly authoritarian and abusive leader of Iraq who

appears to be enabling Iranian arms transfers to Syria.

And remember: We still don't know how this ends yet. Hence

rumors in the Middle East along the lines that all along we planned to create a

"Sunnistan" out of western Iraq, Syria, and Jordan.

Meanwhile, the Iraq war, which we left just over a year ago,

continues. Someone bombed police headquarters in Kirkuk over the weekend, killing 33. And

about 60 Awakening fighters getting their paychecks were blown up in Taji. As my friend Anthony Shadid used to

say, "The mud is getting wetter."

July 25, 2013

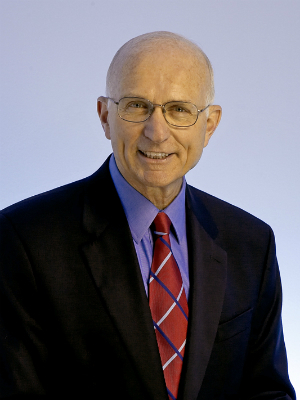

McMaster, Korb, and Iraq: Here is what Tom Ricks missed about my NYT letter

By Lawrence Korb

Best Defense guest

respondent

Like

Tom, I have written many things about Iraq, including outlining the strategic

redeployment (with my colleague Brian Katulis) which became the basis for President

Obama's plan to end our involvement in that mindless, needless, senseless

war. But for reasons of space (letters are limited to 200 words), I could

not include all these points in my letter to the New York Times.

I

do agree with Tom that the military also made huge mistakes in Iraq and needs

to address the two major problems that Tom correctly claims it had in

Iraq. But these problems also were not completely of their own

making. As I have written over and over, the all-volunteer force was

never intended to fight protracted, large-scale wars, and its reserve component

was never intended to be an operational (as opposed to a strategic)

reserve. When the Bush administration decided to invade Iraq while the

nation was still engaged in Afghanistan, it should have activated the selective

service system. Had selective service been activated, the military would

not have had to lower its recruiting standards so drastically (between 2003 and

2007, the ground forces gave 100,000 moral waivers to meet its recruiting goals),

invoke stop loss, soften the criteria for promotion, shorten the time troops

were given between deployments (the standard my office employed when I was in

government was two years at home for every year in a war zone), and hire so

many private contractors with dubious backgrounds who were so difficult to

control.

Also,

I would argue that Tom misses two other big failings of the military.

First,

by publicly supporting the Bush administration's failing strategy, the military

ignored the evidence and extended the conflict. See, for example, then-Lieutenant

General David Petraeus's op-ed in the Washington

Post shortly before the

2004 presidential election,

which painted a bright picture of the situation on the ground in Iraq.

Second,

the military remained silent as manpower and resources were diverted to Iraq

from Afghanistan before the job was finished. Had we not done that, we

would not still be bogged down in that graveyard of empires, and our military leaders were remiss

not to object to such poor strategic decision-making.

Lawrence J.

Korb

is a senior fellow at the

Center for American

Progress

. He is also a senior advisor to the

Center for Defense Information and an adjunct professor at Georgetown

University. Prior to joining American Progress, he was a senior fellow and

director of national security studies at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Lawrence Korb's unhelpful letter today to the editor of the New York Times

Today's

New York Times carries this letter from

Lawrence Korb, who in the early 1980s was an assistant secretary of defense for

manpower, reserve affairs, installations and logistics:

I disagree with Gen. H. R.

McMaster ("The Pipe Dream of Easy War," Sunday Review, July

21) when he attributes our failures in Iraq and Afghanistan to an overreliance

on new technology, which clouded our understanding of the conflicts.

The problems in both wars

were created primarily because President George W. Bush and his advisers

ignored the advice of the Army chief of staff about how many troops to send

into Iraq and the on-the-ground commanders' warnings about disbanding the Iraqi

Army and civil service. Similarly, in Afghanistan they snatched defeat from the

jaws of victory in 2003 by ignoring our military commanders and diverting

manpower and resources to the unnecessary war in Iraq.

This

is the problem I have with Dr. Korb's letter: I worry that it helps enable the

U.S military to go on blaming the civilians for everything that went wrong in

Iraq. Yes, I know the Bush administration made huge mistakes -- like invading

Iraq in the first place, not having a plan for what to do once it got there,

and operating on bizarre assumptions rather than a realistic assessment of the

way forward. In fact, I wrote a book about

all that.

That

said, the U.S. military made huge mistakes as well, but has not had to confront

them nearly as much. The fact of the matter is that our military was badly

unprepared for the tasks facing it in Iraq, especially at the general officer

level. Had the Bush administration listened to General Shinseki and sent twice

as many troops, we likely would have had our poorly commanded troops simply

pissing off twice as many Iraqis. Good strategy will fix bad tactics, but good

tactics will not fix bad strategy, or take the place of no strategy.

Why

do I think the U.S. military has failed to heed the lessons of Iraq? Because I

think that, among other things, it has never addressed two major problems it

had there. The first is torture, the second is the effect of troop rotations on

the conduct of the war. (For example, why did some units torture, and others

didn't? And what was the effect of rotating all but the four stars out every

year?) Korb's letter, and similar expressions, simply make it easier for the

military to go on whistling past the graveyard.

July 24, 2013

How a rogue pilot misbehaved for years in a B-52 squadron, and so killed 4 people

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Feb. 1, 2013.

Of all

the military services, the one I know least about is the Air Force, which

doesn't get a lot of electrons on this blog. So I was especially intrigued to

finally sit down and go through a study sent to me months ago by a Best Defense

reader. "Darker Shades of Blue: A Case Study of

Failed Leadership"

is a thorough, careful study of how leadership lapses over the course of

several years ultimately led to disaster in an Air Force bomber wing. It's also

a beautiful if horrifying exploration of how bad shit can happen despite

volumes of rules and regulations aimed at ensuring safe practices are followed.

Even if

you care nothing about the Air Force, it is a fascinating study of leadership,

and applicable to many different situations. Basically, it is the tale of how

an out-of-control pilot managed to consistently break the rules, but did so

with a clever understanding of how to manipulate the system. So, for example,

he would push the limits until his commander sat him down and gave him an oral

warning. But these were not recorded. So the pilot, who had a reputation as

perhaps the best B-52 pilot in the Air Force, would lay low a bit and then,

when the next commander came in, the pattern would repeat itself. The rogue

pilot got by on a series of these "last chance" reprimands. Subordinates knew

what was going on, and found themselves in the position of either risking their

lives by flying with him, or risking their careers by refusing to do so.

When a

senior officer was told about video evidence showing a recent instance of

flight indiscipline by the free-styling pilot, he responded, "Okay, I don't

want to know anything about that."

Eventually,

on June 24, 1994, a B-52 with the rogue pilot at the controls went down at Fairchild

Air Force Base while attempting a tight 360 degree left turn around the control

tower at 250 feet above the ground. It "banked past 90 degrees, stalled,

clipped a power line with the left wing and crashed," killing four crew members

-- three lieutenant colonels and a colonel.

The key

thing to watch, warns the author, Tony Kern, is "incongruity between senior

leadership words and actions." That is a very important lesson for any

organization.

(A big tip of the official BD baseball

cap to the person who sent me the link a couple of months ago -- I searched all

four of my e-mail accounts and couldn't find who it was, but I appreciate it.)

July 23, 2013

Is there a natural rate of relief of about 9 percent for commanders in combat?

During the summer, the Best Defense is in

re-runs. Here are some favorites that ran in late 2012 and in 2013. This item originally

ran on Jan. 29, 2013.

That's the question

that occurred to me as I read Douglas Allen's fine essay on how the Royal

Navy managed its skippers -- and provided incentives for aggressive approaches

-- during the age of fighting sail. I was struck by his passing observation

that in the mid-18th century, 8.5 percent of its captains were

dismissed or court-martialed.

That's not far from

the rate of relief of 16 out of 155 U.S. Army generals who commanded divisions

in combat in World War II -- the point of departure in my latest book. So I wondered: In organizations determined to enforce standards and

insist on aggressive competence, is there a natural rate of relief of roughly 9

or 10 percent? Business is not the same as military operations, but I also

remember that three decades ago, when I was a Wall Street Journal reporter based in Florida, one of the better

banks in the state, Barnett, had an annual branch manager relief rate of 10

percent. A couple of people also have reminded me that GE, under Jack Lynch,

had a policy of easing out the bottom 10 percent of its managers every year.

But the piece on the

Royal Navy is much more far-ranging. It essentially is a study of how the Navy

leadership of the 18th century addressed the important question of how

to run a large organization with global reach but iffy communications. (The

person who sent it to me was thinking about how one might organize command and

control of a future U.S. space fleet.) It was also a successful organization,

in which, despite being "constantly outnumbered in terms of ships or guns,...still

managed to win most of the time." Professor Allen outlines what he calls "the

critical rules of the captains and admirals" that ensured that commanders would

operate more or less in the interest of the nation rather than in their own.

"The entire governance structure encouraged British captains to fight rather

than run" -- and so also to have crews trained to fight.

Prize money was

especially important. Some senior officers grew rich off the capture of enemy

ships. "At a time when an admiral of the fleet might earn 3,000 pounds a year,

some admirals amassed 300,000 pounds of prize money." The awards also trickled

down: In 1799, when three frigates captured two Spanish ships, each seaman in

the three crews received 182 pounds -- the equivalent of 13 years of annual

pay.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers