Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 50

April 14, 2014

General Mundy in his obituary deserved more than the back of the Post's hand

By Col. Butch Bracknell, USMC (Ret.)

Best Defense guest columnist

The Washington Post's obituary following the passing of General Carl E. Mundy, Jr., the 30th commandant

of the Marine Corps, could have benefited from some balance, perspective, and a

dose of journalistic ethics. The Post

can even make an obituary sensational. Writer Matt Schudel replows old dirt by

resurfacing controversies surrounding certain of General Mundy's public

statements. General Mundy, as a public figure, was of course not immune from

criticism, and this writer would even wager that, if asked, General Mundy would

want a do-over for certain public stances he took as commandant. Even so,

Schudel's research appears to have been Wikipedia deep, as a mere cursory

examination of the historical record might have led him also to note monumental

successes on General Mundy's watch.

Rather than dance on

the grave of an American icon, Schudel might have considered writing a more balanced

account of this gentleman-patriot's life. Over the history of the Corps, some commandants

have been divisive figures, but General Mundy is held in virtually universal

high regard. A warrior who fought in Vietnam at Khe Sanh and Con Thien, with a

gentleman's manner, General Mundy was revered by enlisted Marines, officers,

and his general officers. This author remembers seeing him at Camp Lejeune in

June 2012 at 0530 in the morning as he visited the base to attend the high

school graduation of one of his granddaughters (everyone knows when a

commandant is aboard your base) -- as trim as when on active duty, impeccably

dressed in pressed khakis, a collared golf shirt, clean-shaven with his hair

perfectly combed, returning from a vigorous morning walk. This was

quintessential Mundy -- the epitome of the image that Marine officers work to

project through appearance, carriage, and demeanor.

Schudel's portrait

of this deeply respected Marine leader was inappropriately one-sided. It

painted him with tones of bigotry, reciting his out-of-context comments

regarding African-American Marines's military skills without noting the

enormous progress in the Corps recruiting and retaining minority officers

during his watch. He recited in detail the controversy surrounding his comments

on proposing to limit Marines's right to marry until reaching the rank of sergeant

and women in combat, hinting at an anachronism, out of touch with modern times.

Schudel failed to touch General Mundy's deft guiding of the Corps through force

reductions that saw the Corps emerge from Desert Storm relatively healthier

than the other forces.

Foreseeing the

transition of conflict from state-on-state battles to irregular warfare against

shape-changing, unknown, and unpredictable state and non-state actors, often in

the global littorals, General Mundy steered the Corps in a direction that would

pay dividends for years to come. His tenure as a three- and four-star general

included manning, training, and equipping Marines to fight as a member of the

joint team that demolished the Iraqi Army in Desert Storm, provided

desperately-needed humanitarian relief in Somalia, accomplished the

perfectly-executed rescue of Air Force Captain Scott O'Grady in Bosnia, and

saved thousands of Kurdish lives in Operation Provide Comfort. As America

sought to reap an elusive "peace dividend" with shrinking defense budgets and

uncertain force structure, he guided the Corps through a period of

reorganization with a premium on adequate force levels and readiness that would

yield dividends in Afghanistan and Iraq after 9/11.

General Mundy was

the perfect commandant to follow General Al Gray. General Gray successfully

refocused the Marine Corps on its warrior ethos, and General Mundy carried the

baton forward to even greater levels of maturity, dignity, and professionalism.

Finally, General Mundy's dedication to the men and women of the armed forces transcended

his tenure as commandant, as he presided over the USO and the Marine Corps

University Foundation in retirement. Schudel could have learned all these facts

about General Mundy's successes as a general officer and as the 30th commandant

by picking up a phone and calling Headquarters, Marine Corps, or any Marine

over the age of 35. Instead, in America's paper of record, he elected to rely

on a handful of tired old saws about this fine American, with nary a nod toward

his true excellence in the art of generalship.

Articles like this

deepen the rift between America's warrior class and the self-styled Washington

elite. Marines are a tribe, one that endures valid, even-handed criticism with

a cheerful heart, so long as it is fair and objective. Attacking an icon like

General Mundy by surfacing the controversies of his tenure without placing them

in the context of his enormous strategic successes, on the other hand, raises

our hackles and reinforces the perhaps unwise and unhealthy perception of a

"we/they" split . "We" are the band of brothers, a fraternity forged in the

fire of combat, sacrifice, and service. "They" are Washington's comfortable

privileged class -- on Capitol Hill, in the administration, in the ivory tower

of the academy, and in the media. Most students of wholesome civil-military

relations know well that the split should not, and cannot, be so stark, and

that healthy civil-military relations require outreach and genuine

understandings from both sides. Yet offensive articles such as Schudel's

confirm some Marines's worst suspicions: Rather than take the time to author a

fair retrospective of General Mundy, including his monumental successes and

highly-visible gaffes, the Washington media would rather simply focus on the

latter, at the expense of a fair representation of his achievements.

The Corps does not

expect the media the handle its legacy with kid gloves. We expect to be held

accountable to the American people through several mechanisms -- civilian

control by the president and secretary of defense, congressional oversight, and

the occasionally harsh light of public scrutiny. We only demand that it be

fair, and that any institutional and individual failures be placed in proper

context. Matt Schudel felt no such need to be fair to General Mundy's legacy. This

author cannot speak for all Marines, but this Marine will never forget it.

Butch Bracknell

is a retired career Marine officer and member of the Truman National Security

Project's Defense Council.

Warning to military officers: Don't diss the cops in Monterey, CA, even in your home

They busted an Air

Force captain, a student at the Naval Postgraduate School, after he asked them why they were in his yard.

They later put a

warrant out on him, which may mess up his military career. It seems to me he is

owed a formal apology. This seems like one of those situations where a cop

arrested someone for not being fully respectful -- forgetting that respect is

earned by one's behavior, not owed.

And the cop was on

his property. In America, that counts for something. On the other hand, to

compound his alleged crime, the AF officer was wearing a hoodie.

April 11, 2014

FoW (24): The seven key ingredients of highly adaptive (and effective) militaries

By Col. Keith Nightingale, U.S. Army (Ret.)

Best Defense future of war entry

The there are two

great truths about the future of war.

The first is that it

will consist of identifying and killing the enemy and either prevailing or not.

We can surmise all sorts of new bells and whistles and technologies yet

unknown, but, ultimately, it comes down to killing people. It doesn't always

have to happen, but you always have to prepare to make it happen, and have the

other guy know that.

The other great

truth is that whatever we think today regarding the form, type, and location of

our next conflict, will be wrong. Our history demonstrates this with great

clarity.

Well then, how do we

appropriately organize for the next conflict if both these things are true? There

are a number of historical verities that should serve as guides for both our

resourcing and our management. In no particular order, but with the whole in

mind, here are some key points to consider that have proven historically very

valuable in times of war. The historic degree of support for any one or all

within the service structures usually indicated the strengths and shortfalls of

our prior leadership vision, preparation, and battlefield successes or failures

at the time.

TECHNOLOGY. This

should be heavily invested so our military is on the leading, not trailing edge

of warfare and its tools. It is a given that bad people and bad nations look to

new and unknown elements to provide a leading edge. It was only because of

FDR's instincts that we got a nuclear program ahead of the Germans. Conversely,

had they made earlier investments in jets and long-range submarines, we may

never have had a chance to use our newfound technology. Research &

Development is often shorted for budgetary reasons and is largely unseen and unappreciated

until the other guy's R&D work is demonstrated on the battlefield against

our people. Think IED and cyberwarfare.

INTELLIGENCE. There

can never be enough in enough different ways. Enough is never enough in this

area. This is especially true now with so many bright people, bright ways, and

asymmetric environments. Crucial to all this is HUMINT -- often a dirty word

because it involves risk and judgment -- but usually the only really truly

confirming data point a field commander has. The Iran rescue attempt would

probably have had a far different outcome had quality HUMINT been available.

QUALITY PEOPLE. From

the lowest to the highest grade, quality or lack thereof emerges with great

visibility in the opening period of any conflict. Ineffective organizations

from squad to corps and ships and planes are usually the result of a

disinterest in the stocking, training and education of those personnel and

things. In times of peace, military organizations tend to rest, be selective in

the workloads and if pinched for people, lower entrance standards or excuse

poor performance. People, especially quality people with societal options, cost

money. Within our system, cutting personnel and their costs is usually the

quickest way to achieve savings and the least politically dangerous. It is

always a proven false economy when warfare begins.

ECCENTRIC THOUGHT. Military

institutions traditionally abhor the eccentric. But in times of war, it is the

eccentric that shows the light to seemingly insurmountable problems and

provides field elements a priceless edge. Consider the World War II Higgins

Boat and ULTRA programs -- both were the brainchildren of people thought beyond

the pale by the conventional military of the time. All the services have

schools and "future think" programs that could harbor the unusual mind. There

are people within the population that seem to be in another universe and viewed

as distasteful by the system. But they may also hold the only flashlight for a

dark room problem besetting a combat zone. The services should create a small

place in their structure for these people and encourage their play. It has

always paid dividends.

LANGUAGE &

CULTURE. It's more than likely that our next war will be fought in a place we

don't now know where there is a language and culture we may not fully

understand. We will lose people because of that. There is also a distinct

possibility that the nature of that future fight will encompass civilians and

the necessity of convincing them as to our quality. The services need to

encourage and build on an internal knowledge base of great diversity, expertise,

and cultural flexibility. Some small node of that base will be priceless at a

critical moment. The crucial need is always at the cutting edge of human interface

-- a place where this sort of education is historically not taught in favor of

rote tactics. How much money did DOD have to spend to allow small units to

effectively work in our latest wars for translators and cultural support

personnel?

DEPLOYABILITY. The

most effective unit in our inventory is irrelevant if it can't get someplace in

time to make a difference. Historically, this is an area beset with specific service

agendas and is non-glamorous from a funding perspective. Amphibious lift and

air deployability have been traditional tail-end budget items for services

enamored with big ships and fast planes. It is highly likely that wherever our

next conflict is, it won't be in the United States. Getting there will be

important. Consider the heroic and somewhat amusing efforts it took to get land

combat units to Kuwait -- think Liberty Ships. If Saddam had been more

aggressive, our initial elements would have been speed bumps and their members

memorialized. We can do a lot better but it takes visionary discipline and

resources.

LEADERSHIP. Someone

will always be "in charge" at all levels. This is an oft-used phrase within the

military but not often truly defined or nurtured. Whatever the state of quality

our forces have at a moment of conflict, the existing leadership will make the

decisions and we will live with the results. McClellan or Marshall -- you get

what you got with what you developed. Truly defining this quality, determining

how to select quality and educating quality will be crucial. Leadership puts

all the above aspects into qualitative action -- or doesn't. Our success or

lack thereof will be determined by the quality of leadership at all levels at

the moment of commitment. Even without desired resources, future quality

leaders at all levels and tasks can have the vision and mindset to effectively

overcome issues, determine the most effective solutions, and inspire success. This

is the one area, above all, that cannot be neglected. Nor should we be

dependent on a momentary find of a personality that "doesn't fit the mold." Quality

will be demanded at all levels -- especially at the very top and bottom.

Leading in peace has

always been the greatest challenge for the services. The usual lodestones for

success do not exist. Proving the necessity for existence is always a major

budgetary challenge. The senior leadership is constantly trying to find the

Philosopher's Stone that turns a little into a lot. Leadership is further

hampered by both internal service pet rocks as well as congressional

proclivities. History indicates that the successful military Philosopher's

Stone can rarely be identified in the whole, but we do know some of the parts.

Col. (Ret.) Keith Nightingale commanded Airborne and

Ranger/SOF infantry forces from company through brigade. He participated in the

combat spectrum from the Dominican Republic through the Iran rescue attempt to

Afghanistan, as well as in drug interdiction operations in Latin America. He

annually conducts Normandy terrain walks for U.S. military participants in the

anniversary period.

Tom note: Got

your own list o f long-held truths about the future of war?

Consider submitting an essay

. The contest ends soon. Try to keep it short -- no more than

750 words, if possible. And please! no footnotes or recycled war college

papers.

One of the best military reading lists ever: Direct to you from the Australian army

It's been awhile

since I've seen a reading list this good, and so comprehensive. An education itself. One

thing I especially like about it is that it doesn't just list books, it tells

you why you might want to read each one.

It also has some

very helpful introductory essays. For example, there is this comment on how to

read an official history:

Learn

to read between the lines, particularly the lines of the official histories.

Official historians expect their professional readers to be able to read

between the lines. For example in speaking of Singapore, the War Office history

says, 'Many stragglers were collected in the town and sent back to their

units.'

What

does this statement suggest? In an advance stragglers are to be expected. Men

become detached from their units for quite legitimate reasons. We provide for

them by establishing stragglers' posts to collect them and direct them back

towards their units. But when we get large numbers of stragglers behind a

defensive position, and a long

way back at that, it suggests that units have been broken up or that there has

been a breakdown of discipline somewhere. And that in turn suggests that the

general situation had reached the stage when a lot of people had lost

confidence, when morale was at least beginning to break down.

Also, General Paul

Van Riper's essay on his own professional education is worth an evening all by

itself.

April 10, 2014

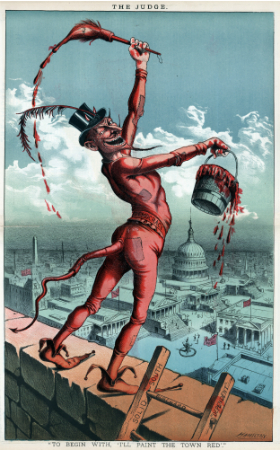

Sherman's (VII) pet peeves: He loathed reporters, DC, politicians, and even JAGs

Everyone

knows that Sherman didn't want to run for

president, but I didn't realize how deep his loathing of politics overall ran.

This was despite his being the brother of a lifelong politician, John Sherman, who was a senator and

also secretary of the treasury and secretary of state.

In

April 1861, as the Civil War was getting under way, he was offered the post of

assistant secretary of war. He declined, responding, "I wish the Administration

all success in its almost impossible task of governing this distracted and

anarchical people."

In

1868, when President Andrew Johnson tried to transfer Sherman east from St.

Louis to Washington, Sherman said he'd rather retire from the Army. He

explained that he found the idea of moving to Washington "highly objectionable,

especially because it is the political capital of the country, and focus of

intrigue, gossip and slander."

Underscoring

his objection, he wrote to Grant that if the president and Congress would just

shut up and go to sleep, "the country would ... recover far faster."

Another

pet peeve was reporters. "Newspaper correspondents with an army, as a rule, are

mischievous. They are the world's gossips, pick up and retail the camp scandal,

and gradually drift to the headquarters of some general, who finds it easier to

make reputation at home than with his own corps or division."

As

for JAGs: "The presence of one of our regular civilian judge-advocates in an

army in the field would be a first-class nuisance, for technical courts always

work mischief."

By

the way, the general is tweeting his march through Georgia at @TecumsehSays. Typical tweet: "Went well, had some fun, burned

some stuff, you know, the usual."

The top 10 lies Pakistani officials tell

From

the tell-it-like-it-is Prof. Christine Fair. No. 1 is, "Our

relationship should be strategic rather than transactional." Second is that it

is us, not them, that has been an unreliable ally.

Here

is a link to the rest.

What stolen valor incidents tell us about frayed ties between military and society

By Maj.

Brad Hardy, U.S. Army

Best

Defense guest columnist

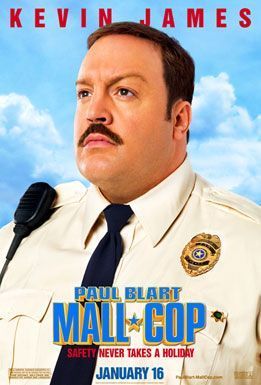

A recent news story by KSL-TV in Salt

Lake City linked to by the Stolen

Valor Facebook page reported on a military

fraud named Kenneth Crocheron. With kindness in his heart, Crocheron posed as a

Special Forces officer in an attempt to bring comfort to a local boy stricken

with a rare disease. It was a touching intent, but with a misguided method. Crocheron's

lie about current military service grew and his backstory expanded to a

breaking point. The ill boy's family investigated and outed Crocheron as a

fake.

At least one has to admire

Crocheron's boldness. Just one look at his broad, goofy smile belies anything

but a man convinced no one would call him on it. Maybe he assumed the veterans

in his midst were too timid to say anything and his Gaddafi-esque collection of awards would dazzle the uninformed civilian. Crocheron's

pictures are hilarious and tragic at the same time, and they should make the soldiers

laugh and cringe at the absurdity. Further, his story of stolen valor and many

others like it show a disconnection between trust in the military and an

understanding society.

Crocheron's story went on for some

time, at least since 2007. And cases of stolen valor are nothing new. But, for something like this to go on as long

as it did says two things about our society. First, it indicates that the Army

remains a trusted and admired profession, but almost to a fault. The Army's

manual on the Profession of Arms, Army Doctrine Reference Publication (ADRP) 1,

states that "trust reflects the confidence and faith that the American people

have in the Army to effectively and ethically serve the Nation, while resting

assured that the Army poses no threat to them." A broad assumption is that

civilians will tend to defer to the military to do the right thing. Maybe it's

the professed values, generally honorable conduct in war, authoritative tone,

uniform, haircuts, or heroic portrayal in movies. But jokers like Crocheron,

even if unaffiliated with the Army, erode that earned trust. Society may start

to second-guess the confidence and question their faith that ADRP 1 touts. The

Crocherons of the world destroy public trust in the Army by exploiting it. He

abused it to gain unearned prestige and access to a family's young child. The next time that family

sees a uniformed servicemember, they may not be so supportive. The next

civilian that reads about another case of stolen valor may not believe the

legitimate war stories of real returning soldiers.

Now the critical observer may assert

that the Army has nothing to do with the likes of Crocheron or similar phonies.

This is certainly true. The Army is in the awkward position of defending this

skewed sense of the freedom

of speech. But the service does not want these

crooks to besmirch its proud tradition and uniform. Only an active citizenry that

knows its military and, further, desires to keep trusting it may be the one

bulwark against a bad reputation.

This is the second point. This event

shows that society may have only a passing knowledge about its military,

uniforms, combat operations, and history. For many, these aspects of military

culture remain esoteric and distant, only showcased in commercials and parades.

It's not an indictment, but perhaps shows just how separated the armed forces are from the society it serves. Crocheron

could have served in both Vietnam and Afghanistan as he claimed. It's been done

before. But no one questioned the claim's feasibility. No one thought

how odd a one week deployment to Afghanistan sounded. The gestalt of his

uniform's disorganized appearance raised no red flags until much later. No one

knew until a veterans group said everything was a scam.

This situation demands that the

civilian population grows to know the military they fund and send to war on its

behalf. Civilians should do it, if not to prevent the short-term embarrassment

of deception, than to grasp what their long-term defense investment is. But

also, it indicates that the Army has not done such a great job at advocating

its own culture in way that civilians know enough to spot imposters.

Blindly accepting claims of military

service can make innocent citizens look or feel foolish and resentful. Further,

near-automatic deference, confidence, and faith in a powerful institution,

instead of thoughtful questioning and examination of its actions and intent,

are dangerous attitudes. Objective critical examination of the government and

its agencies feels pretty darn patriotic and serves as a sound civil

responsibility. With a closer look, the citizen may be pleased to learn of lost

stories of heroism that were ultimately honored. But one's fear may be that the civilian would not like what he

finds, such as the seedy actions of some our senior

leadership. It is only through this regular

examination that society will gain a greater understanding and appreciation of

its military and perpetuate the trust it needs for legitimacy. Without trust

and legitimacy, the Army becomes an army.

I would be encouraged if the casual

man on the street knew so much about the military he funds. I want him to, and

hope my brothers- and sisters-in-arms continue to tell the good Army story. But

my fear is that, all too often in the mind's eye, the Army is relegated to pop

culture concepts and tear-jerking redeployment reunion videos. If the Army

continues to act either only ‘over there' in a way that allows the general

population to remain unaffected, or on a cloistered installation, or with an

indecipherable acronym language, indifference will continue. Choruses of "thank

you for your service" will suffice as proper homage, much like attending church

at Christmas and Easter constituted the religious experience of my youth.

I am reminded of the tale of the wolf, sheepdog, and sheep. The story goes that the Army

is the sheepdog, protecting the sheep (citizens), from the wolf or those who

would do the sheep harm. It is very encouraging to the soldier and may touch him

with bit of hubris. But I think that we need more sheepdogs geared toward

another form of guard duty. We need more sheepdogs examining the military and

the policy we fulfill. We need more civilian sheepdogs that are on the watch

for the phony as well as on guard for Army culture.

However, the

greatest onus to make a difference is on the Army. No matter how special we may

think we are, the Army really is not so different and separate an organization.

As a part of society, the Army must do better at educating the society it

serves about its culture so that future scam artists are detected. The Army

must continue to share its culture, as it is part of the broader fabric of

American heritage. The military and American experiences have always combined

to make us who we all are and show where we have been as a society. So, fellow

sheepdogs, let's not let the two drift too far apart.

MAJ Brad Hardy is a U.S. Army officer, Functional Area 59 (Army

Strategist), and unapologetic University of Akron alumnus and Akron Zips fan.

The opinions expressed in the article are solely those of the

author and do not reflect those of the U.S. government, the Department of

Defense, or the U.S. Army.

April 9, 2014

The real question isn't naval presence but how to best empower U.S. partners in Asia

By

Captain Paul Lushenko, U.S. Army

Best Defense guest respondent

No one

questions the U.S. Navy's utility. The issue at stake, however, is how to

achieve the best balance between the services to (1) provide for regional

security and order while (2) meeting America's security obligations to its

allies and partners, especially Australia, Japan, and South Korea. While the

Navy, as both a ‘way' and ‘means,' as you point out, can help achieve both

‘ends,' your analysis is parsimonious to the point of obfuscating, particularly

the diplomatic or messaging dividends of deploying land-based forces across the

region.

In a

region beleaguered by a mélange of threats and vulnerabilities, epitomized by

North Korea's increasingly brazen machinations and natural disasters

respectively, the Navy can't do it all

or by itself. Here, think of the U.S. Army's equally important response to

Japan's 3/11 or its live-environment training exercises on the Korean Peninsula

that do much to reassure regional-states -- again, especially allies -- of

America's staying power.

Among

other things, the dispatch of land-based forces is designed to placate allies

and partners as well as deter potential challengers, namely the Chinese

party-state on account of its reputed revisionism. All of these actors

increasingly question the viability of America's so-called ‘pivot' or rebalance

towards the Indo-Pacific. Such uncertainty is based not only on sequestration

and its attendant spending caps, but the recent denigration of U.S. soft power

given the country's failures in Iraq and Afghanistan and its frustrated

management of global security challenges including Syria's implacable civil war

and Russia's annexation of Crimea. If you don't believe me, perhaps you'll

appreciate this recent article published by the New York Times, titled "U.S. Response to Crimea Worries Japan's

Leaders."

Moreover,

because the Navy is not necessarily omnipresent -- unlike you, I disagree that

the Navy can be everywhere at once on the basis of simple math, logistics, and

manning -- land-based forces provide a tangible and stable deterrent. Do you

think North Korea or China's provocations would be lessened if the Pentagon removed

land-based forces on the peninsula and in Okinawa, respectively? Do you think

Russia might also abrogate its competing claims to the Kuril Islands vis-à-vis

Japan as well?

The

answer is no. Such redeployment would undermine America's regional hierarchy or

"hubs and spokes" alliance system that has provided security throughout Asia

since WWII, attenuate any offshore-balancing thereafter, and encourage more

insouciance regarding the procedural norms that frame regional and

international order, including sovereignty and territorial respect. Within a

regional context, this is a damning proposition given that it would countermand

or unravel the intent of especially Southeast Asian states to shepherd a

security order based on consensus and consultation. Since its promulgation in

1967, the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation, published by the Association of

Southeast Asian Nations or ASEAN, has provided the basis for resolving regional

challenges like competing irredentist claims or lingering war memories through

cooperative and diplomatic measures. With respect to 'HADR' missions on the

other hand, who do you think provides the situational awareness and collects against

intelligence requirements that focuses the Navy's presence and assistance? That's

right, land-based forces.

What

frightens me about your analysis, notwithstanding that it is informed by a

recent deployment throughout the antipodes, is that it may actually represent a

standing position among at least a segment of the Navy. While I concur that

funding amid sequestration should be tailored against the most important

capabilities, your position represents a veritable gutting of one aspect of the

hard-power component of America's rebalance, albeit an important one -- the U.S.

Army. Meanwhile, your argument is myopically focused on what America provides

the region in terms of materiel, training, and so forth. The more astute point

would have been, especially given ongoing shifts in the regional security order

embodied by China's "peaceful rise," how America can best deputize its regional

allies and partners. Put differently, what can and should policymakers and

senior leaders expect from allies and partners by way of burden-sharing? To me,

this seems the more important issue given that, amid a probable continuation of

sequestration, such a broader distribution of security responsibilities enables

longevity of American influence across the region largely unencumbered by

fiscal constraints.

Finally,

I think you should have focused on the ‘joint' pay-offs of investing in both

the Army and Navy. Recall, seven of the world's 10 largest armies are

positioned within the Indo-Pacific. Does investing in the Navy alone achieve

parity with these forces, especially if it is blinded or ‘fettered' by the

China's anti-access strategy? No.

In the

event of a states-based conflict, you'll appreciate that the historical trend

has been that nothing is won until it is occupied. Admittedly, the wars in Iraq

and Afghanistan have demonstrated that even this paradigm is now subject to

scrutiny, particularly given a movement towards ‘armed politics,' whereby great

powers pursue military action more as policy than to condition political

objectives. Nevertheless, it seems that victory (definitions of this hotly

contested word aside) is predicated on occupation, something that the Navy,

based on its mission and training (the Marine Corps is fundamentally about

gaining a lodgment) cannot and will not provide.

In the final

analysis, I think you failed to realize that we are as much brothers-in-arms as

we are services-in-arms.

Best of

luck and stay safe.

Paul

Captain Paul Lushenko is the Commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 502D Military

Intelligence Battalion, assigned to the 201st Battlefield Surveillance Brigade

at Fort Lewis, Washington. He is a Distinguished Honor Graduate of the U.S.

Military Academy and holds a Master of Arts in international relations and a

Master of Diplomacy from the Australian National University. Capt. Lushenko is a friend of

Lt. Robb

, who was his twin brother's roommate at the U.S.

Naval Academy. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and

do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Department of the Army, Department of

Defense, or government.

Why Sherman (VI) preferred volunteers

General Sherman ranks volunteers, draftees, and subs: "I think all officers of

experience will confirm my assertion that the men who voluntarily enlisted at

the outbreak of the war were the best, better than the conscript, and far

better than the bought substitute."

Lee surrendered to

Grant on this day.

Churchill denounces fighting the Afghans but concludes my empire, right or wrong

In 1897, Winston

Churchill wrote to his mother summarizing his views of the British fighting the

Afghan tribes: "Financially it is ruinous. Morally it is wicked. Militarily it

is an open question, and politically it is a blunder." But, he continued,

according to Con Coughlin's new book, Churchill's

First War, "we can't

pull up now." He emerged more determined than ever to defend the British

Empire.

Speaking of cleaning

up the detritus of the British Empire, the president of Ireland is making the first-ever state visit to Britain by an Irish head of state.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 437 followers