Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 52

April 3, 2014

FoW (23): The biggest growth industry in defense should be counter-drone systems

By Capt. Adam Thomas, USMC

Best

Defense future of war entry

There

have been a lot of conversation as of late regarding the rise of unmanned

systems (UxS) and how they are going to play a large role in future warfare. The

proliferation of these future systems is not only going to be used by states

but also non-state actors. This is an obvious fact but raises the question, how do we counter such unmanned systems that

can be acquired and weaponized by almost anyone?

With

all new technologies there is usually a double-edged sword when it comes to its

utility. A basic search on the Internet can allow anyone to find, purchase, and

outfit an unmanned system, whether it is an aircraft or ground system, and

employ it using their own creative devices. So, back to the original question:

How do we combat this proliferating technological capability? There are

multiple methods to examine. It depends on whether you want to kill, disable,

deny, or take control of the UxS. Future warfare development will have to focus

on how to counter these systems because there is no Department of Defense (DOD)

monopoly on this technology.

Future

adversaries will be capable of utilizing the Internet and mass media to gain

visibility and control the message they want the world to see. Due to

commercial technologies, they will be highly networked, which will allow them

to shape the battlefield quicker than U.S. forces, and they will be able to

exploit our own rules of engagement to gain decisive advantages and mass and

engage our military on their own terms. Using their own UxS, they will have

access to real time intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance that will

prove lethal if we don't find a way to counter this capability. Research and

development within private industry and the DOD has to be seriously focused on

a counter-UxS effort if we are to maintain our predominance on future

battlefields.

Capt. Adam Thomas,

USMC, is a helicopter pilot who works on counter-unmanned systems projects at

the Marine Corps Warfighting Lab. The

views in this post are those of the author alone and do not reflect the

views of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Marine Corps.

Disappointment in USNI's tendentious response to recent item on aircraft carriers

Last

week some of you may have noticed that I posted an item criticizing Proceedings, the journal of the U.S.

Naval Institute, for running an article by an

admiral about how great carriers are, without taking note of all the arguments made recently by

others about how carriers may be the battleships of the 21st century -- that

is, looking quite powerful but actually being quite vulnerable, and incredibly

expensive to build, equip, and operate.

On

the day the item ran, Tuesday, I gave Proceedings's

editor a heads-up about the item. Since then, I have received a series of

complaints and accusations from the journal's publisher and from a retired

admiral who is on the USNI board. I invited them to send along a response that

I promised to post promptly. Instead, they escalated and started complaining to

my editors. "Admiral Timothy

J. Keating, USN (Ret.) is a director of the U.S. Naval Institute, and asked

that we forward his letter to the editor based on his reaction to a recent Tom

Ricks post on Best Defense," wrote Bill Miller, the

publisher. "He submitted a comment to the original post that was not

published, quite astonishing considering that Ricks railed about one-sided

debates in that post."

Two

points here that long-time readers know are true:

I

welcome dissenting responses, and run lots of them. Indeed, last week I

repeatedly asked the USNI people to send me a response. They did not.

I

have no control over comments on this blog, and don't want to. As I have said

before, I am a First Amendment fundamentalist, and I also think that editing out

offensive material only helps the offending parties look better. Thus I don't

see comments before they are posted. I see them when you do.

Yet the USNI guys persist in believing and

asserting that I somehow suppressed Admiral Keating's comment. Indeed, Admiral

Keating this morning sent me an e-mail that seems to me to accuse me of quashing

it and then lying about it: "We had no opportunity to respond in a

timely fashion. I submitted my post within a day, as is reflected in the blog

comment queue. You say you didn't receive my post. I would say that bears a

closer look."

Normally I wouldn't

mention all this behind the scenes wrangling, but Keating's questioning of my

integrity pissed me off. I think he probably screwed up posting his comment and

is now are trying to pin that on me. But even if he is technologically

challenged, that shouldn't have been a problem, because last week I repeatedly

asked Miller and his editor, Paul Merzlak, to send me Keating's comment. If

Keating couldn't post it, I told them, I would. But they didn't send it.

Given this

experience, my opinion of Proceedings

continues to decline. And yes, they are welcome to respond to this. They have my

e-mail address if they need help.

A view from the high seas: The Navy is now more important than other services because it provides unfettered presence

By Lieutenant Doug

Robb, U.S. Navy

Best Defense guest

columnist

The

shifting strategic focus of the United States, alternately referred to as a

"pivot" or "rebalance," has crystalized a debate among our national leadership

about how the military can and should achieve its security goals in the coming

years. At the operational and tactical levels, it is irrefutable that we must

have an adequate number of highly-capable warships -- and a sophisticated

logistics system to support them -- operating forward and ready for tasking to

maintain the timely, efficient, and metered response to which we have become

accustomed.

Ships

and their capabilities are tools ("means" in military parlance) used to achieve

tactical, operational, and strategic objectives ("ends"). However, they differ

from other military hardware because a constant naval presence -- simply "being

there" -- has characteristics of both ends and means. As a result, the

"one-third, one-third, one-third" budget allocations traditionally apportioned

among the service branches simply will not achieve current or future security

goals. Policymakers should recognize not only the immense payoff that naval

forces provide, but how they can strengthen America's security prospects in the

years to come.

However,

the debate about the size and capability of the U.S. Navy must not narrowly

view ships as "means" to a tactical "end." Rather, it should acknowledge that

the routine non-wartime presence Navy ships maintain is an end itself -- one

that delivers tangible benefit to American security, influence, and

responsiveness unmatched by any other service or platform.

Unique to the Navy's

routine presence mission is the ability to provide these security requirements

in near real-time without the requirement of a host country. Naval forces are

inherently different from Army garrisoned forces because, while long-term land

occupations risk undermining security objectives, a strong naval presence can

reinforce them. Maritime forces require no diplomatic approval to operate in

international waters; they do not force domestic or foreign leaders to expend

political capital in order to place troops within striking distance of hot

spots; they do not put allies in awkward positions by asking them to house U.S.

forces when the local population may be averse to such presence.

Conversely, large

garrisoned forces require policymakers in both the United States and in the

forward-deployed country to make decisions that could weaken broader security

goals. For example, an augmented American ground presence in Germany or Poland

would surely increase regional tensions already stoked by the crisis in Crimea.

Moreover, it would be difficult for military strategists to argue that placing

such forces in Europe would help the outlook in the Pacific, where our security

focus will be for the foreseeable future.

The

ship on which I serve, the USS Kidd

(DDG 100), illustrates the value routine naval presence provides. Kidd recently concluded its 10-day search for missing Malaysia

Airlines Flight 370;

this journey took the ship from the Gulf of Thailand to the Java Sea, through

the Singapore Strait and Strait of Malacca, past the Andaman Sea and on to the

Bay of Bengal at the northern edge of the Indian Ocean. In total, Kidd transited more than 3,500 nautical

miles conducting visual and radar searches; its two MH-60R helicopters used

state-of-the-art sensors to comb nearly 15,000 square nautical miles during

round-the-clock sorties.

While

some may claim it was "luck" that Kidd

and Pinckney (DDG 91), which also

participated in the operation, were able to respond to this tragedy so quickly,

this timely reaction was made possible only by the U.S. Navy's continued and

persistent presence in the Indo-Asian region. Kidd was conducting routine operations in the South China Sea -- only

a one-day transit from the initial search location. "Luck," said Branch Rickey,

the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers who signed Jackie Robinson, "is the

residue of design."

The

U.S. Navy's presence in neighboring waters permitted a rapid response to the

search effort for the missing jetliner without the cost that would result from

deploying a San Diego or Pearl Harbor-based ship. Conversely, a deployment

announced specifically for the Flight 370 search might have sent a potentially

negative signal to the Malaysians that the U.S. distrusted their search

process.

Moreover,

the transit time (no less than three weeks) would have limited the value of the

U.S. contribution. This same logic applies to humanitarian assistance, disaster

relief, or any other situation in which tensions rise and threaten free access

to waterways essential to U.S. economic and security interests. Deploying to

these areas after an event occurs or tensions flare -- especially when American

naval presence has historically not been routine -- can limit the efficacy of

response and might well raise the very apprehensions the Navy's presence was

meant to quell.

The

Navy is omnipresent in every major geographic area around the world. The very

presence of naval ships simultaneously deters military aggression and assures

our allies, safeguards the sea lanes and the commerce that flows through them,

preserves territorial waterway boundaries and the right to resources contained

therein, and facilitates a response to natural disasters and other catastrophes

-- like the disappearance of MH370. In this case, showing up is well more than

half the battle.

The

U.S. Navy's resilience can only endure with the understanding that a firm

commitment to building and maintaining a first-rate Navy -- capable of being

present where our national interests lie -- is not only desirable, it is

necessary. This commitment is a policy prerequisite if the United States -- a

maritime nation whose interests have been safeguarded by the Navy since the

country's founding -- wants to retain the ability to influence outcomes, create

additional windows of diplomacy, and control escalation.

Lieutenant Robb holds

graduate degrees in security studies from Georgetown's School of Foreign

Service and the U.S. Naval War College. He currently serves as the operations officer of the USS Kidd (DDG 100) on deployment in the Asia-Pacific. The views

expressed are his alone.

April 2, 2014

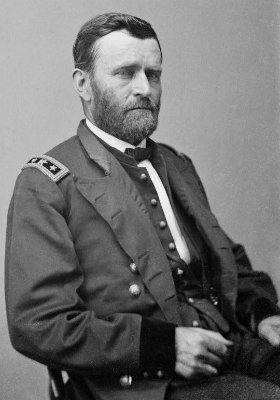

How mission command works: Sherman's memoirs (III) show that it is based in trust, and must work as a two-way street

Mission command is a

two-way street, as is illustrated beautifully in the Civil War letters between

General Grant and his subordinate, General Sherman.

The letters,

reproduced in Sherman's memoirs, demonstrated how Grant communicated his

intent to Sherman, then offered his suggested course of action, and finally

asked Sherman for his thoughts. "In this letter," Grant wrote to Sherman upon

hearing that the march across Georgia had reached the sea, "I do not intend to

give you any thing like directions for future action, but will state a general

idea I have, and will get your views after you have established yourself on the

sea-coast."

Grant initially had

some notion that Sherman might move his infantry by sea to Virginia, but

Sherman really wanted to visit the

hard hand of war upon South Carolina. In Georgia he had focused on seizing or

destroying the property of plantation owners, but he next wanted to chastise

the South Carolinians as a whole for starting the Civil War. He wrote to Grant

that, "With Savannah in our possession ... we can punish South Carolina as she

deserves.... I do sincerely believe that the whole of the United States, North

and South, would rejoice to have this army turned loose on South Carolina." He

also thought it would help increase the pressure on Lee in Virginia.

Grant, persuaded by

Sherman's arguments, and his tone, agreed. "Your confidence in being able to

march up and join this army pleases me, and I believe it can be done. The

effect of such a campaign will be to disorganize the South, and prevent the

organization of new armies from their broken fragments.... Without waiting

further directions, then, you may make your preparations to start on your

northern expedition without delay. Break up the railroads in South and North

Carolina, and join the armies operating against Richmond as soon as you can."

Sherman's summary of

mission command comes later in the book, in his conclusions about the lessons

of the Civil War. It is pretty good: "When a detachment is made, the commander

thereof should be informed of the object to be accomplished, and left as free

as possible to execute it in his own way."

A puzzlement to me: Why two of my favorite writers sat out World War II

I love reading E.B.

White and W.H. Auden. Both are lovely writers and good observers. Yet I find I

fundamentally distrust both, because both essentially sat out World War II.

Neither was a conscientious objector, a position I respect. White at least grew

chickens on a farm. Auden simply left England, still a relatively young man at

age 32. I think it leaves a hole in the works of both.

So as I read, and

nod in agreement, or underline, I hear a little voice: "Yes, but...."

Maybe it is the end of 'counterinsurgency' -- but the beginning of 'armed politics'

My friend retired

Army Brig. Gen. Jim Warner comments that, "I personally

would prefer to stop talking about counterinsurgency and deal with what is in

effect armed politics. If we thought about it that way it might be more useful

in practice."

April 1, 2014

The Future of War (entry no. 24): The key tool we will need to prevail is … empathy

By

Major Daniel Leard

Best Defense

future of war essay entrant

I have always been a fan of science fiction. My father

raised me on the greats: Heinlein, Hubbard, and Asimov. Each story brought a

unique twist on future possibilities, but these literary pioneers, who were

among the first to view the future as radically different from their own time,

contained a common theme: Human history will always be human.

No matter how alien, mechanical, or fantastic the future

might be, human empathy would remain among the most influential forces in the

world. The history of warfare and its future are no different. Empathy has

always been vital in battle, and it is our empathic capacity that will

determine our success in future conflict. With some evidence suggesting that

empathy in America is in decline, renewing our understanding of empathy and its

role in warfare, acknowledging our shortcomings in empathic reasoning, and

increasing our empathic capacity are vital concerns for military leaders.

Empathy is the ability of human beings to understand each

other. This understanding begins with self-awareness and radiates out toward

others -- friends and foes alike. It is the ability to see through another's

eyes and understand the world as they see it. It was empathy (not Styx's waters)

that made Achilles immortal with sword and spear. To feel his opponents'

passion, fear, and perspective attuned him to strengths and vulnerabilities,

imminent blows and opportunities for attack. Empathy stood at the heart of Sun

Tzu's missive to generals: "know your opponent and know yourself, in a hundred

battles you will never be in peril." And empathy gave Otto von Bismarck the

foresight to make peace with a defeated Austria following the Battle of

Koniggratz when conventional wisdom advised a pursuit to annihilation. In war,

no other skill has been so vital to all -- soldier, strategist, and statesman.

However, as the range of our weapons increased, the

perceived utility of empathy on the battlefield diminished. No longer did the

soldier have to hold his fire until he saw "the whites of their eyes," and the

days would not be far off when soldiers could pull triggers that killed men on

other continents. In time, empathy for the enemy among U.S. strategists and

policymakers would also disappear. Gaetano

Ilardi observed that immediately following 9/11, empathy was

categorically absent and unwanted: "To empathize was to sympathize. To

sympathize was unimaginable, and unforgivable." This mentality generated much

of the political and military hubris that led to a number of the blunders in

Afghanistan and Iraq. To make matters worse, some studies indicate that empathy

among young Americans has steadily declined for the last three decades. If this

is true, even our most senior military leaders may be among the affected

population.

Though empathy may be lacking, a decade of conflict has

reminded us of its enduring value. Even now, we desperately want and need it.

We call for it with ideas such as cultural competence and emotional

intelligence. We create doctrine and concepts for human domains and dimensions

and engagement warfighting functions. Old lessons and habits, once forgotten,

can appear novel when rediscovered. Our efforts to quantify and codify this

skill of understanding and influencing people demonstrate just how far empathy

has slipped into clouded memory. In our search for empathy in the force, it is

essential that we appreciate its importance in our future. As discussed,

empathy is not sympathy. It does not produce a "kinder, gentler" force. Rather,

greater empathic capacity will improve our ability to employ lethality with

increased precision and discern the value of restraint in any given situation.

Energetic theorists, like science fiction writers, give us

varying ideas of what tomorrow may look like, and in some cases, they may be

correct. Future war may in fact be more urban, dominated by cyberspace, or

shaped by drones, robotics, or improvements in human performance. The cult of

big data promises that computers will understand and predict our adversaries'

actions far better than mere mortals can. These promises have their allure, but

at its core, warfare -- even the wildest visions of cyber-powered, push-button

warfare -- has always been and will always be subject to the complexities of

the human mind, and the human mind can only be reliably interpreted in kind.

Regardless of how sophisticated (or simple) a sword our future enemies may

wield -- a rifle, roadside bomb, tank, or keystroke -- the quality of our

defense will owe more to our understanding of ourselves and our attackers than

our technological prowess. This is a talent that only empathy can provide, and

most importantly in these financially lean times, it is a talent that costs

relatively little to engender.

Major

Daniel Leard is a U.S. Army infantry officer who is currently a student at the

Command and General Staff College. He holds a bachelor's degree in history from

West Point and is currently completing a master's program. The views presented

in this essay are the author's and do not represent those of the Department of

Defense.

Sherman (II) recalls a Civil War battle fought over some fields of blackberries

Sherman mentions in

an aside in his memoirs that there was once combat between skirmishers from the federal government

and the rebels over fruit. "I have known the skirmish-line, without orders, to

fight a respectable battle for the possession of some old fields that were full

of blackberries."

This was not just a

matter of good taste. Blackberries were useful in warding off scurvy, and so

particularly valuable when other antidotes, such as lime juice, pickles, and

sauerkraut, were unavailable.

British sniper kills 6 Taliban with one shot

At 850 meters, too.

No, they weren't lined up. The British sharpshooter, a lance corporal in the Coldstream Guards,

hit the trigger switch on the vest of a suicide bomber. When his bomb

detonated, it killed the five people standing around him.

March 31, 2014

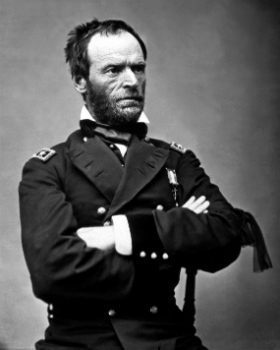

1st thoughts on Gen. William Sherman's memoirs: Clarity in writing and warfare

When I was in Austin

I picked up for $2.50 a used copy of both volumes of the memoirs of General William T. Sherman.

The first thing that

struck me was how clear his writing is, especially in issuing orders. In that

he was like Grant, but I think maybe even better in expressing his intent. Here,

for example, is part of his order for his march across Georgia, in which he set

off with about 60,000 and almost no supplies.

In districts and

neighborhoods where the army is unmolested, no destruction of property should

be permitted; but should guerrillas or bushwhackers molest our march, or should

the inhabitants burn bridges, obstruct roads, or otherwise manifest local

hostility, then army commanders should order and enforce a devastation more or

less relentless.

Like a good counterinsurgent,

he wanted to visit his wrath on the intransigent while sparing the friendlies

and the neutrals, telling soldiers they should be "discriminating ... between

the rich, who are usually hostile, and the poor and industrious, usually

neutral or friendly."

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 437 followers