Thomas Zinser's Blog, page 2

February 27, 2014

Breathtaking Video Footage from Intl. Space Station

February 23, 2014

Mind – Beyond Where the Brain Leaves Off

January 10, 2014

Mind Shift: The Idea That WILL Change Everything

I know you’re not supposed to give away the ending before telling the story, but in this case, I think it’s all right. This post is an extract from Marcus Anthony’s book, The Great Mind Shift, and it ends the with this statement.

I know you’re not supposed to give away the ending before telling the story, but in this case, I think it’s all right. This post is an extract from Marcus Anthony’s book, The Great Mind Shift, and it ends the with this statement.

If I am to answer the question “What will change everything?”, I would answer that the coming great mind shift will dramatically change life, science, education and business. The historical and scientific evidence points to the fact that consciousness is not merely a product of the brain and is entangled with people, nature and cosmos. The shift is inevitable. The next question then becomes, “Are you ready?”

Anthony is another voice confronting the limitations of empirical science and announcing a paradigm shift from “brain” to “mind.” In this excerpt, he warns against a science that would turn men into machines, because it is the only language they understand. Another case of ”if it’s all you see, then it’s all you’ll get.”

Like Siegel and Goleman in the previous posts, Anthony points to a science that recognizes consciousness and mind.

Tom Z

The Idea That WILL Change Everything

Written by Marcus T. Anthony DECEMBER 18, 2013 in Conscious Evolution, Conscious Living, Futurism, Sci-Tech with 0 Comments

Some time ago I picked up a copy of John Brockman’s This Will Change Everything: Ideas That Will Shape the Future. The volume contains a collection of short essays by more than one hundred influential scientific and philosophical minds, including Daniel Dennett, Paul Davies, Richard Dawkins, Steven Pinker, Freeman Dyson, and Rupert Sheldrake. Each of these people was asked the following question:

“What will change everything? What game-changing scientific ideas and developments do you expect to live to see?”

Naturally, respondents brought forward a wide range of subject matters including synthetic biology, robotics, the benefits and dangers of artificial intelligence, quantum computing and the discovery of alien life.

But what interested me during my reading was getting a sense of what these one hundred brightest minds thought about the nature of consciousness; and in particular about the extended mind and related ideas like telepathy, remote viewing and so on. For me this was a good opportunity to gauge how open mainstream science is to what I call “the great mind shift” – the time when the non-local nature of mind will become mainstream in science and psychology.

The answer is that the vast majority of writers in This Will Change Everything do not mention the subject of the extended mind; and those that did framed the issue in a paradigmatically bounded way, dismissing it with contempt.

In his essay entitled “A Change in Who we Are,” Paul Zachary Myers, associate professor of biology at the University of Minnesota, writes that one major shift:

… is coming from neuroscience. Mind is clearly a product of the brain, and the old notions of souls and spirits are looking increasingly ludicrous. Yet these are nearly universal ideas, all tangled up in people’s rationalisations and ultimate reward or punishment and in their concept of self.

The great irony here is that the belief that the brain produces mind is an unexamined presupposition of modern neuroscience, and has no direct evidence (although there is a clear correlation between brain states and both perception and behaviour).

Zachary Myers goes on to write:

This will be our coming challenge: to accommodate a new view of ourselves in the universe that isn’t encumbered by falsehoods and trivialising myths. That’s going to be our biggest challenge: a change in who we are.

Zachary Myers’ statement represents a further irony because entanglement (spooky connections at a distance in quantum physics) and the extended mind threaten modern biology’s founding presupposition of the mechanistic nature of life; which I predict in time will be shown to have both mythic and “false” elements. The mechanistic paradigm – the idea that the universe is hung together like a great machine and all life is essentially mechanical – is an invisible narrative which underpins much of modern science and especially neuroscience. It is the verification of the entanglement of mind and nature that will most certainly challenge our notions of who we think we are.

The restrictive thinking displayed in This Will Change Everything suggests that current mainstream science tends to acknowledge the concept of entangled minds only where machines mediate the process. Of the few scientists willing to discuss ESP in the book, all invoke the necessity of a machine interface as an explanatory mechanism. Kenneth W. Ford, for example, believes that we will soon be able to read signals from brains—but only with machines. Ford writes:

We can probably safely assume that the needed device would have to be located close to the brain being read… We could let Mind Reader, Inc, make and market it.

Such thinking appears to be driven by what I call a “money and machines” mentality, and is suggestive of the way that science has become embedded within – and restricted by – the commercialisation of science and education.

Similarly, Freeman Dyson, in an essay entitled “Radiotelepathy,” sees telepathy operating via mechanical means, assisted by microwave signals penetrating the flesh of the brain and detected by a mechanical device outside. Freeman writes:

A society bonded by radiotelepathy would experience human life in a totally new way… We will feel in our own flesh the community of life to which we belong. I cannot help hoping that the sharing of our brains with our fellow creatures will make us better stewards of our planet.

Such an argument, in yet a further irony, has long been posited by mystics, philosophers, and thinkers with a spiritual bent. Only they see such a connected mind as being a natural, innate expression of human intelligence. No machines required.

Parapsychologist Dean Radin has often employed the term “the psi taboo” to describe the way that most mainstream scientists and philosophers reject all notions of psi phenomena, including the extended mind – regardless of what evidence is put before them. The psi taboo seemingly makes many mainstream thinkers reluctant to be associated with ideas which support the hypothesis that consciousness has non-local properties.

Throughout his essay, “Slippery Expectations,” Corey S. Powell rates the likelihood of certain groundbreaking developments happening in his lifetime (he was sixty-two years old at the time of writing). Powell gives “the end of oil” a ninety-five percent probability. The discovery of dark matter is rated ninety percent likely. He also believes that there is an eighty percent chance that he will live to see genetically engineered children.

But what of telepathy? Once again, the key for this thinker is whether there are machines involved. Powell gives a full seventy percent chance that synthetic telepathy, mediated via “rudimentary brain prostheses and brain-machine interfaces,” will be a reality within the next thirty years. He writes:

Transmitting specific, conscious thoughts would require elaborate physical implants to make sure the signals go to exactly the right place—but such implants could soon become common anyway, as people merge their brains with computer data networks.

It is interesting to compare these estimates of Powell’s to some other controversial domains of science to which he refers. He writes that the development of “conscious machines” is fifty percent likely while he is still alive. Communication with other universes is given a ten percent chance, and there is even a five percent chance of the development of an anti-gravity device.

What, then, are the odds of the verification of actual human ESP? According to Powell there is currently:

… nary a shred of evidence to support the idea—unless you count reports of dogs who know when their owners are about to return home and people who can “feel” when someone is looking at them… Everything I know about science and human objectivity says there’s nothing to find here.

While Powell does concede that this is the one discovery that really would change everything, he then goes on to give the chances of its verification in his lifetime as being precisely half of one percent.

Given that several meta-analyses of studies into telepathy and other of psi-related phenomena have delivered significant results against chance in the millions and even billions to one, it is reasonable to query why Powell feels the need to give the odds of its verification as being a full fifty times less than the chance of the development of an anti-gravity device. (Indeed Dean Radin has recently provided a summary of the most useful evidence from peer-reviewed research here).

The mechanism for the existence of gravity is not currently understood, much less that for an anti-gravity device. Further, no human being has ever experienced an anti-gravity device, nor does anti-gravity inform a legitimate experience for contemporary human beings. Compare this to the widespread belief in and experience of psi-related phenomena.

Further, we can note Powell’s assessment that the development of machine consciousness is five hundred times more likely than the chance of concrete evidence for telepathy emerging. This is despite the fact that the emergence of consciousness from brains remains a mystery, and that there is currently no adequate explanation (mechanism) which might explain how a non-conscious, mechanical system might become conscious. Why, then, is Powell five hundred times more confident of the development of the artificial replication of mind in his lifetime than he is of the confirmation of telepathy?

Clearly, Powell’s attitudes toward these three concepts reveals a mindset which is not “rational” in the literal sense of the word.

Perhaps the most revealing statement made by Powell is his admission that “everything I know about science and human objectivity says there’s nothing to find here.” Beyond the likelihood that Powell simply has not read the literature on the subject, his ignorance indicates that he has simply never gone to the inner spaces, nor explored the ways of knowing that make mystical insights and the connectedness of minds understood at a personal level. For it is in inner, meditative, and mindful experience that direct insight into the extended mind is commonly experienced.

This Will Change Everything is a fascinating read; but sometimes it because of what is missing, rather than because of the thinking contained within its pages. The book provides confirmation that much thinking is inevitably constrained by social, cultural and paradigmatic boundaries.

If I am to answer the question “What will change everything?”, I would answer that the coming great mind shift will dramatically change life, science, education and business. The historical and scientific evidence points to the fact that consciousness is not merely a product of the brain and is entangled with people, nature and cosmos. The shift is inevitable. The next question then becomes, “Are you ready?”

* * *

Marcus T Anthony, PhD, is Director of MindFutures. He refers to himself as a futurist, intuitive and life alignment coach. He is the author of Discover Your Soul Template and his website iswww.marcustanthony.com.

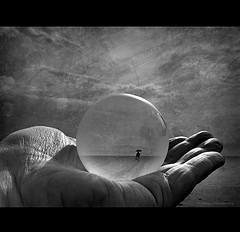

Photo: http://www.flickr.com/photos/onefromrome/228705707/sizes/n/

December 21, 2013

The Mind Beyond Brain

This post is a follow-up to the previous one on Dr. Dan Siegel and his model of the mind.

This is an excerpt from an article by Bernard Kastrup, Ph.D. entitled, Transcending Our Brain Created Reality: A New Call to Lift Nature’s Veil. I recommend the full article. You can find it here.

Dr. Kastrup goes further than Siegel to talk about the non-ordinary states of consciousness that are veiled by the psychological filters, both biological and cultural.

Tom Z

Looking Beyond the Veil

Solid evidence has been accumulating that our minds cannot be explained solely by brain activity; the mind seems to transcend the brain. Yet, it is undeniable that the brain plays a significant role in our perceptions and behaviour, as, for instance, the effects of alcoholic drinks make plain and clear.

In an earlier article in this magazine,5 I elaborated upon an alternative hypothesis for explaining the relationship between the mind and the brain; a hypothesis that, since the publication of that article, has gained increased scientific momentum: Consciousness is a fundamental aspect of nature, not depending on any material structure for its existence. The function of the body-brain system is to localise and restrict conscious perception to the space-time locus of the physical body. As such, the brain modulates and limitsconscious perception, this being why, in ordinary states of consciousness, mental states correlate so well with brain states.

As we’ve seen in the discussion above, such restriction and modulation of conscious perception – that is, the filtering and distortion of the copy of reality in our brains – can have a significant survival advantage, which explains why the brain evolved to perform such counterintuitive tasks.

Now, because the brain works as a kind of filter of mind, restricting and distorting our view of reality for survival purposes, bypassing certain brain mechanisms could conceivably give one access to a broader, cleaner, crisper, and more reliable view of nature. Historically, most, if not all, methods for achieving non-ordinary states of consciousness seem to do precisely that: To enable expanded perception and understanding by reducing brain activity.

The pattern here is so clear that it is surprising our culture seems to remain largely oblivious to it. For instance, many traditional Yogic breathing practices, as well as the more modern method of Holotropic Breathwork, reduce brain activity through the constriction of blood vessels that results from hyperventilation (which is precisely why you to get dizzy and ultimately faint when breathing too fast). Military pilots undergoing G-force induced loss of consciousness (G-LOC) – which forces blood out of the brain, thereby reducing its activity – are known to report transcendent narratives similar to near-death experiences. Teenagers worldwide play a dangerous, potentially fatal game involving partial strangulation in order to ‘trip’ without drugs.

Even psychedelic substances, which have always been assumed to produce ‘hallucinations’ by stimulatingbrain activity, have recently been shown to actually reduce brain activity.6 At least two Nobel Prize laureates – Francis Crick and Kary Mullis – have attributed their prize-winning insights to such non-ordinary states of consciousness; a powerful corroboration for the notion that such states broaden understanding and increase insight, despite reduced brain activity. Even more subtle methods, like meditation, ritual prayer, and sensory deprivation (think of isolation tanks) are likely associated to decreased brain activity.

The pattern here is as clear as it is ancient: Specific reductions in brain activity seem to consistently lead to a broadened and crisper perception and understanding of reality. The hypothesis that the brain is a mechanism to constrain and localise mind is entirely consistent with this: Reduction of brain activity impairs the filter/localisation mechanism, allowing one to temporarily and partially escape its entrapment and come closer to perceiving reality as it truly is.

A tantalising possibility suggests itself, one that has been lost to Western culture perhaps since the extinction of the Eleusinian mysteries: An unfathomably broader and more authentic inquiry into the true nature of reality can be achieved through an expansion of the investigator’s own state of consciousness. That true inquiry involves not only the transcendence of physical limitations through the use of instrumentation, but – and more fundamentally – a transcendence of one’s own brain-based mental filters. To see and understand reality for what it truly is – to see the original, not the flawed copy – we need to temporarily escape the limitations imposed on us by biology and culture.

November 24, 2013

‘Mindsight’ and the Soul

I recently watched an interview with Dr. Dan Siegel hosted by the Dalai Lama Center. It impressed me in the same way it had several years ago when I first watched Dr. Siegel present his model of the mind and brain. It’s the best effort I’m aware of so far to establish a concept of mind as more than the biology and chemistry of the brain. He brings together a wealth of research from many areas to support his model of the mind.

While Dr. Siegel does not use the term soul in his model of the mind, what I see as so important is that his model does not exclude it. If you watch the video, you could substitute the term soul at several points in Dr. Siegel’s discussion. When he talks about the “We-map,” the “hub”, the “open possibility,” he could just as easily be talking about the soul and soul level reality.

This video is an excellent introduction to his work.

Tom Z

Dr. Siegel has number of videos on Youtube in which he talks about the mind. Click here for a list.

October 1, 2013

The Practice of Soul-Centered Healing: A Book Review

The Practice of Soul-Centered Healing – Vol. 1: Protocols and Procedures

Review by Dr. Alan Sanderson

To follow a masterpiece with a second book on the same subject and have another shining success is no small achievement. Tom Zinser has done just this. In the first book, he told how his thought had developed during a quarter century of intense therapeutic effort, undertaken with the expert guidance of Gerod, channelled by an acquaintance. Now he presents a detailed account of the diagnostic and therapeutic system that he uses with his clients.

Following trance induction and the establishment of ideo-motor signals, the first step is to gain permission from the protective part of the mind to establish communication and then to make contact with the higher self, which becomes co-therapist in the work of Soul-Centered Healing.

After confirming that the higher self is in agreement with the healing process, and that communication is not blocked by another part or being (throughout the book every eventuality is carefully addressed), the inquiry proceeds. The higher self is asked to review the problem area and determine whether something or someone is interfering at an energetic, psychic or spiritual level. Following the usual yes, the root of the problem is approached via yes/no/don’t know answers, along the steps of the Identification Protocol, with its eight possibilities. Each identified part or being, ego-state, spirit, extraterrestrial, dimensional being, created entity, external ego-state, device/object and autonomous energies is then examined along the steps of its own Clinical Protocol. Final resolution is reached through integration, removal, dissipation and severance of ties, etc., as required. In this process the higher self is consulted at every step and performs many actions on request.

The combination of clarity and precision that Zinser brings to the text and the many illustrative sessions provide perfect instruction for any therapist wishing to learn the techniques. I would advise any one wishing to acquire proficiency in SCH to read these sessions repeatedly, giving your own response to each yes/no/don’t know answer, before checking with the one given.

SCH is carried out by two agents, therapist and higher self. The higher self, through its inner connection to the Light, is an invaluable helper, for it perceives much of which the conscious mind is unaware and it is able to affect directly the various entities, which inhabit the inner world. It can also call helpers from the Light, when an entity seems to be in need of more direction than the therapist knows how to provide. The simplest and most powerful tool is for the higher self to send Light, but this must be agreeable to the ego-state, spirit or other being, to whom it is offered. To induce calm and cooperation in this way is by no means the equivalent of a calming injection imposed on a disturbed hospital patient. In the inner world, acceptance must, with rare exceptions, precede every action. Here is a session in which an ego-state receives Light from the higher self.

TH – Higher self, I’m asking that you help that ego-state to come forward here with me. (Pause.) And to this one: do you know yourself to be part of this self and soul I’m working with?

ES – No finger lifts.

TH – Are you willing to have some information sent to you about your connection to this self/soul?

ES – Yes finger lifts.

TH – Okay then. On the count of three I’m going to ask the higher self to send you this information. One, two, three, and higher self, please communicate to this one information about whether they are or are not part of this self and soul. Also, please communicate any other information that might be helpful, especially about the healing process we are working with. And to this one: lift the yes finger when you’ve received that communication, second finger if you do not.

ES – Yes finger lifts.

TH – To this one: did you receive this communication all right?

ES – Yes finger lifts.

TH – Does it seem that you are part of this self and soul? First finger if yes, second finger if not.

ES – First finger lifts.

TH – Are you receiving Light for yourself now where you are?

ES – Hand lifts. (I don’t know)

TH – To this one: are you willing for higher self to send you some Light/Love energy right now?

ES – Hand lifts. (I don’t know)

TH – To this one: are you willing to have that Light sent to you as long as you can stop it immediately if you need to, or if you like it, you can keep it for yourself, but the choice will be up to you? The Light will not force itself on you.

ES – Yes finger lifts.

TH – On three then: One, two three… and higher self please send to this one a small piece of that Light/Love energy. And to this one: let yourself receive that Light. You can stop it if you need to, or, if you like it, you can bring it inside and keep it for yourself. First finger lifting when you’ve touched that Light, second finger if you do not.

ES – First finger lifts.

TH – To this one: did you receive that Light?

ES – Yes finger lifts.

TH – Did you decide to keep the Light for yourself? If so, the first finger. If you needed to stop it, the second finger can lift.

ES – First finger lifts.

TH – To this one: would you like more of that Light/Love energy for yourself?

ES – Yes finger lifts.

TH – Higher self, I’m asking, then, that you send this one more of that Light/Love energy. And to this one: you can bring that inside to whatever level is comfortable. First finger when that feels complete. Second finger if it’s stopped.

ES – First finger lifts.

TH – To this one: did you receive that Light all right?

ES – Yes finger lifts.

TH – Does that feel all right to you?

ES – Yes finger lifts.

Another transformative use of the Light is when an entity that is unsure of its soul identity is asked to look inside for its own light. This can be a great convincer.

Soul-Centered Healing is a revolutionary form of psychotherapy. Nothing even remotely like it has ever been developed before. Its systematic nature is demanded by the complexity of the soul-environment that Zinser, with the advice of a channelled being, has unearthed through his research. If the approach seems over-mechanical, this is misleading. Administered with the required sensitivity the effect is finely balanced.

As a therapist who has used the method, I want to stress how very carefully it has been developed. Every conceivable difficulty seems to have been described and the solution set out with precision and clarity. Despite the technicality, the book is a pleasure to read. It is a hard road to travel, but those of us who would make the journey can be assured that, with Zinser’s guidance, we can enter the land where Soul-Centered Healing can be given and received.

About the reviewer

Dr Alan Sanderson Alan Sanderson trained as a psychiatrist – in the 1950s and 60s, at St Thomas’s and Maudsley Hospitals, London – but became disillusioned about the overall direction of the medical approach, which focussed on the disease, not the illness – and so losing contact with the patient as an individual. He found a new direction from studying with Bill Baldwin from America and went on to found the Spirit Release Foundation. He now practices ‘soul-centered’ therapy from his home in London. For details see:www.alansanderson.co.uk/

Dr Alan Sanderson Alan Sanderson trained as a psychiatrist – in the 1950s and 60s, at St Thomas’s and Maudsley Hospitals, London – but became disillusioned about the overall direction of the medical approach, which focussed on the disease, not the illness – and so losing contact with the patient as an individual. He found a new direction from studying with Bill Baldwin from America and went on to found the Spirit Release Foundation. He now practices ‘soul-centered’ therapy from his home in London. For details see:www.alansanderson.co.uk/

September 15, 2013

The Courage to Find Soul: A Call for More ‘Psyche’ in Psychology

The word “psyche” is also the word for soul; accordingly, psychology could be considered to be the art and science of healing and nourishing the soul. But what if healing and nourishing our souls means to take a path that is less pretty than we want? What if the soul is like an inner activist — disrupting our status quo, creating imbalance, finding nourishment in illness that unsettles our usual lives, moving us not only into the light but also into the darkness, and rendering us unsure of even our most cherished beliefs? Would you still follow her?

The word “psyche” is also the word for soul; accordingly, psychology could be considered to be the art and science of healing and nourishing the soul. But what if healing and nourishing our souls means to take a path that is less pretty than we want? What if the soul is like an inner activist — disrupting our status quo, creating imbalance, finding nourishment in illness that unsettles our usual lives, moving us not only into the light but also into the darkness, and rendering us unsure of even our most cherished beliefs? Would you still follow her?Consider the following cases:

Case 1: Brad, a multi-millionaire, retired in his early 50s. He worried about money all the time. He was almost obsessed with counting it and reviewing his budget; he was afraid to spend too much, limiting himself to spending only a portion of the interest he made each month while his net worth grew. Therapists and friends told him to spend more, worry less, go on the vacations he fantasized, buy the luxury car he eyed, and send his lower-income friends plane tickets to visit him. But he couldn’t.

“Maybe I’ll never get over this worry. Maybe it’s the legacy of my father, who was incredibly frugal and anxious about money.” Instead of trying to relieve him of his worry, I assumed that his worry was meaningful taking him in a new direction in his life about money and more. I asked him to tell me what it was like to worry about money. He became vulnerable, sensitive, and even fragile. As he spoke, I noticed that we were growing more intimate than we had been before, and our conversation wandered onto new topics, including his desire to help build homes for people who couldn’t afford one and his deep love for animals. His worry about money was a doorway giving him access to his more tender feelings and care for others — his connection with humanity. His worry was an invitation, a teaching, not an illness to be relieved.

Case 2: Sue regularly fought with her father; she became angry whenever she thought of him. She worked to let go of her anger, but it always returned. I asked Sue to show me the anger with her hand. She made a fist and her jaw began to protrude. I asked this angry part of her, “What kind of person are you?” She replied, “I do what I want, go for what I want. I don’t take sh-t from anyone.”

As she learned to be more like this in many areas of her life, not just with her father, her resentment with him began to fade. Her anger gave her access to her power — a power that was meant to be used, not meditated away.

Case 3: Sally suffered bouts of depression and was afraid to get pulled down again. She had been there before; it wasn’t pretty. I said, “Let’s go down together; let me be your eyes and ears and see what we can find.”

We sunk together, first into a low mood, then into tears and sadness. I asked, “Dear sadness, why have you come?” She replied, “I miss the hopes and dreams I had when I was a child; somehow they got lost along the way.” Thank goodness for her depressed state; without it she would never have remembered the life that she really wanted.

We naturally seek to rid ourselves of anything that interferes with our goals and sense of wellness. We fight against depression — we “anti” depress. We meditate hoping to make our anger go away or practice mindfulness to stop ourselves from being so damn hungry. We learn communication skills in order to listen better, speak more directly, and avoid hurtful conflicts. We try to muster sufficient resolve to free ourselves from bad habits and addictions. As men, we treat our softness, especially if it shows up in our penises, as something to be ashamed of and corrected (making Viagra one of the largest selling drugs on the planet). As women, we obsess about our body shapes and sizes (making the diet industry a $60 billion gold mine). In short, we look at everything that disturbs us as an enemy to overcome or a disease to be treated, fixed, removed, and made to go away.

But what if treating and overcoming our symptoms takes us away from our deeper healing? What if those things that disturb us the most are keys to our authentic selves? What if the “medicine” we really long for can be found cooking, alchemically, right in the center of what we think of as illness? What if bringing an attitude of love and awareness to our problems instead of treating and fixing them is what really nourishes our souls? Would you take that path — would you follow your soul?

Photo Credit: h.koppdelaney via Compfight cc

September 4, 2013

Psychiatric Drugs: Big Money, Poor Science

As a hypnotherapist, psychiatric drugs are an important issue in my practice. Many of my clients come to me already taking one or more psychiatric drugs – mostly anti-anxiety, anti-psychotics, or anti-depressants. A couple of years ago, a client was taking seven prescription drugs, four of which were psychiatric drugs. Her psychiatrist – part of the public mental health system – strongly resisted my client’s efforts to wean herself off the drugs.

In the past month, I’ve come across several articles and videos about 1) the overuse of drugs in our society, especially psychiatric drugs, and 2) the lack of any scientific basis or theory for explaining the relationship between biochemistry and mental illness.

In the beginning , it must have seemed like a marriage made in heaven. Big Pharma stumbled onto a huge new market and psychiatrists were promised a science of mental illness and legitimacy in the medical world. It doesn’t seem to be working out that way.

As the following article points out, advances in psychopharmacology are almost at a standstill. Most psychiatric drugs are copycats of one another. If this continues, it will leave Big Pharma with a dwindling market and psychiatry without a science.

The bottom-line is whether people suffering with emotional and psychological distress are gaining any effective treatment other than being sedated and numbed. Here is the first of several posts on this issue.

Tom Z

THE PSYCHIATRIC DRUG CRISIS

Gary Greenberg is a practicing psychotherapist and the author of “The Book of Woe: The DSM and the Unmaking of Psychiatry.”

It’s been just over twenty-five years since Prozac came to market, and more than twenty per cent of Americans now regularly take mind-altering drugs prescribed by their doctors. Almost as familiar as brands like Zoloft and Lexapro is the worry about what it means that the daily routine in many households, for parents and children alike, includes a dose of medications that are poorly understood and whose long-term effects on the body are unknown. Despite our ambivalence, sales of psychiatric drugs amounted to more than seventy billion dollars in 2010. They have become yet another commodity that consumers have learned to live with or even enjoy, like S.U.V.s or Cheetos.

Yet the psychiatric-drug industry is in trouble. “We are facing a crisis,” the Cornell psychiatrist and New York Times contributor Richard Friedman warned last week. In the past few years, one pharmaceutical giant after another—GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Novartis, Pfizer, Merck, Sanofi—has shrunk or shuttered its neuroscience research facilities. Clinical trials have been halted, lines of research abandoned, and the new drug pipeline has been allowed to run dry.

Why would an industry beat a hasty retreat from a market that continues to boom? (Recent surveys indicate that mental illness is the leading cause of impairment and disability worldwide.) The answer lies in the history of psychopharmacology, which is more deeply indebted to serendipity than most branches of medicine—in particular, to a remarkable series of accidental discoveries made in the fifteen or so years following the end of the Second World War.

In 1949, John Cade published an article in the Medical Journal of Australia describing his discovery that lithium sedated people who experienced mania. Cade had been testing his theory that manic people were suffering from an excess of uric acid by injecting patients’ urine into guinea pigs, who subsequently died. When Cade diluted the uric acid by adding lithium, the guinea pigs fared better; when he injected them with lithium alone, they became sedated. He noticed the same effect when he tested lithium on himself, and then on his patients. Nearly twenty years after he first recommended lithium to treat manic depression, it became the standard treatment for the disorder.

In the nineteen-forties and fifties, schizophrenic patients in some asylums were treated with cold-induced “hibernation”—a state from which they often emerged lucid and calm. In one French hospital, the protocol also called for chlorpromazine, a new drug thought to increase the hibernation effect. One day, some nurses ran out of ice and administered the drug on its own. When it calmed the patients, chlorpromazine, later named Thorazine, was recognized in 1952 as the first drug treatment for schizophrenia—a development that encouraged doctors to believe that they could use drugs to manage patients outside the asylum, and thus shutter their institutions.

In 1956, the Swiss firm Geigy wanted in on the antipsychotics market, and it asked a researcher and asylum doctor, Roland Kuhn, to test out a drug that, like Thorazine, was an antihistamine—and thus was expected to have a sedating effect. The results were not what Kuhn desired: when the schizophrenic patients took the drug, imipramine, they became more agitated, and one of them, according to a member of the research team, “rode, in his nightshirt, to a nearby village, singing lustily.” He added, “This was not really a very good PR exercise for the hospital.” But it was the inspiration for Kuhn and his team to reason that “if the flat mood of schizophrenia could be lifted by the drug, then could not a depressed mood be elevated also?” Under the brand name Elavil, imipramine went on to become the first antidepressant—and one of the first blockbuster psychiatric drugs.

American researchers were also interested in antihistamines. In 1957, Leo Sternbach, a chemist for Hoffmann-La Roche who had spent his career researching them, was about to throw away the last of a series of compounds he had been testing that had proven to be pharmacologically inert. But in the interest of completeness, he was convinced to test the last sample. “We thought the expected negative pharmacological results would cap our work on this series of compounds,” one of his colleagues later recounted. But the drug turned out to have muscle-relaxing and sedative properties. Instead of becoming the last in a list of failures, it became the first in a series of spectacular successes—the benzodiazepenes, of which Sternbach’s Librium and Valium were the flagships.

By 1960, the major classes of psychiatric drugs—among them, mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and anti-anxiety drugs, known as anxiolytics—had been discovered and were on their way to becoming a seventy-billion-dollar market. Having been discovered by accident, however, they lacked one important element: a theory that accounted for why they worked (or, in many cases, did not).

That didn’t stop drug makers and doctors from claiming that they knew. Drawing on another mostly serendipitous discovery of the fifties—that the brain did not conduct its business by sending sparks from neuron to neuron, as scientists previously thought, but rather by sending chemical messengers across synapses—they fashioned an explanation: mental illness was the result of imbalances among these neurotransmitters, which the drugs treated in the same way that insulin treats diabetes.

The appeal of this account is obvious: it combines ancient notions of illness (specifically, the idea that sickness resulted from imbalanced humors) with the modern understanding of the molecular culprits that make us suffer—germs. It held out the hope that mental illness could be treated in the same way as pneumonia or hypertension: with a single pill. Drug companies wasted no time in promulgating it. Merck, the manufacturer of Elavil, commissioned the psychiatrist Frank Ayd to write a book called Recognizing the Depressed Patient, in which he extolled the “chemical revolution in psychiatry” and urged doctors to reassure patients they weren’t losing their minds, but rather suffering a “common illness” with a “physical basis” and a pharmacological cure. Merck sent Ayd’s book to fifty thousand doctors around the country. In 1965, Joseph Schildkraut, a psychiatrist at the National Institute of Mental Health, reverse-engineered antidepressants and offered an actual theory: at least when it came to depression, the imbalances were to be found in the neurotransmitters he thought were affected by the drugs, dopamine and norepinephrine. Seven years after antidepressants were invented, and five years after Ayd asserted that depression was a chemical problem, psychiatrists finally had a precise, scientific explanation for why they worked. The paper quickly became one of the most cited articles in the medical literature.

But Schildkraut was wrong. Within a few years, as technology expanded our ability to peer into the brain, it became clear that antidepressants act mostly by increasing the availability of the neurotransmitter serotonin—rather than dopamine and norepinephrine, as previously thought. A new generation of antidepressants—the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (S.S.R.I.s), including Prozac, Zoloft, and Paxil—was developed to target it. The ability to claim that the drugs targeted a specific chemical imbalance was a marketing boon as well, assuring consumers that the drugs had a scientific basis. By the mid-nineties, antidepressants were the best-selling class of prescription medications in the country. Psychiatry appeared to have found magic bullets of its own.

The serotonin-imbalance theory, however, has turned out to be just as inaccurate as Schildkraut’s. While S.S.R.I.s surely alter serotonin metabolism, those changes do not explain why the drugs work, nor do they explain why they have proven to be no more effective than placebos in clinical trials. Within a decade of Prozac’s approval by the F.D.A. in 1987, scientists had concluded that serotonin was only a finger pointing at one’s mood—that the causes of depression and the effects of the drugs were far more complex than the chemical-imbalance theory implied. The ensuing research has mostly yielded more evidence that the brain, which has more neurons than the Milky Way has stars and is perhaps one of the most complex objects in the universe, is an elusive target for drugs.

Despite their continued failure to understand how psychiatric drugs work, doctors continue to tell patients that their troubles are the result of chemical imbalances in their brains. As Frank Ayd pointed out, this explanation helps reassure patients even as it encourages them to take their medicine, and it fits in perfectly with our expectation that doctors will seek out and destroy the chemical villains responsible for all of our suffering, both physical and mental. The theory may not work as science, but it is a devastatingly effective myth.

Whether or not truthiness, as one might call it, is good medicine remains to be seen. No one knows how important placebo effects are to successful treatment, or how exactly to implement them, a topic Michael Specter wrote about in the magazine in 2011. But the dry pipeline of new drugs bemoaned by Friedman is an indication that the drug industry has begun to lose faith in the myth it did so much to create. As Steven Hyman, the former head of the National Institute of Mental Health, wrote last year, the notion that “disease mechanisms could … be inferred from drug action” has succeeded mostly in “capturing the imagination of researchers” and has become “something of a scientific curse.” Bedazzled by the prospect of unraveling the mysteries of psychic suffering, researchers have spent recent decades on a fool’s errand—chasing down chemical imbalances that don’t exist. And the result, as Friedman put it, is that “it is hard to think of a single truly novel psychotropic drug that has emerged in the last thirty years.”

Despite the BRAIN initiative recently announced by the Obama Administration, and the N.I.M.H.’s renewed efforts to stimulate research on the neurocircuitry of mental disorder, there is nothing on the horizon with which to replace the old story. Without a new explanatory framework, drug-company scientists don’t even know where to begin, so it makes no sense for the industry to stay in the psychiatric-drug business. And if loyalists like Hyman and Friedman continue to say out loud what they have been saying to each other for many years—that, as Friedman told Times readers, “just because an S.S.R.I. antidepressant increases serotonin in the brain and improves mood, that does not mean that serotonin deficiency is the cause of the disease”—then consumers might also lose faith in the myth of the chemical imbalance.

August 28, 2013

Helping Lost Souls Move into the Light

No matter what you read in the mainstream media, or hear from materialist science, spirits do exist. The real problem is that we have so little knowledge and understanding of spirits and the spirit realms. Scientists can’t get a handle on these realities because they are not physical, and so cannot be reduced to sensory data. I’m confident that future science will develop the concepts and the technology for exploring these realities. The exciting thing about it is that when science crosses that boundary, it will signal an expansion of consciousness, individual and collective.

No matter what you read in the mainstream media, or hear from materialist science, spirits do exist. The real problem is that we have so little knowledge and understanding of spirits and the spirit realms. Scientists can’t get a handle on these realities because they are not physical, and so cannot be reduced to sensory data. I’m confident that future science will develop the concepts and the technology for exploring these realities. The exciting thing about it is that when science crosses that boundary, it will signal an expansion of consciousness, individual and collective.

Meanwhile, on this everyday level, there are people who suffer the negative effects of spirit intrusion or attachment who are looking for relief and cannot wait for science and the medical field to catch up. These people traditionally seek help from a priest, a shaman, a medium, and increasingly, from hypnotherapists. Most people in our Western culture do not know how extensive the literature is on these kinds of spirit interactions until they or someone close to them is affected by such an entity. There’s a good chance that you, or someone you know, has seen, felt, or been in communication with a spirit at some point in life, and for many, the interaction is a source of distress and confusion.

Two months ago, I was invited to London to give a talk at a one-day conference entitled: Spirit Release: Helping Lost Souls Move into the Light. I spoke on the issue of spirit intrusion and attachment and the most effective way of helping clients resolve this situation. There were five speakers, and each of us spoke from our clinical experience on dealing with lost and earthbound spirits, whether they are attached to places or to people.

The conference was hosted by the Spirit Release Forum and chaired by David Furlong. Videos of all the talks, including a Q & A period at the end, have generously been made available on the Web site at Spirit Release Forum. This series of talks will give you a well-rounded introduction to the issues of spirit intrusion and attachment.

May 13, 2013

Soul-Centered Healing: 3-Day Training Workshop

Spirit Release and Soul Centered Healing

Training Workshop For Clinicians and Therapists

A 3 Day Experiential Training Workshop

with Dr. Tom Zinser on a special trip from the United States,

Monday to Wednesday, 24-26 June 2013, Malvern, England

Soul-Centered Healing is a therapeutic modality that recognizes every person as a physical, psychic, and spiritual being. It also recognizes that there are phenomena, entities, conditions, and forces operating at these levels that can be a source of a person’s pain, fear, or confusion.

Soul-Centered Healing is a therapeutic modality that recognizes every person as a physical, psychic, and spiritual being. It also recognizes that there are phenomena, entities, conditions, and forces operating at these levels that can be a source of a person’s pain, fear, or confusion.

In this three day workshop, Dr. Zinser will discuss the psychic and spirit dimensions of the self, what they mean in our everyday experience, and what can go wrong at these levels to cause serious problems and distress. He will discuss the energetic, psychic, and spirit phenomena that can present in a person’s healing process. These include a person’s higher self; sub-personalities (past life and present); attachment or intrusion by spirits or other kinds of beings; blockages involving etheric devices or energies (created within the self/soul or introduced from outside).

In the workshop, Dr. Zinser will describe how these phenomena can co-exist and interact with each other to create conflicts and entanglements for a person at these inner levels. He will discuss the basic protocols for identifying and dealing with each kind of phenomenon as it presents in the healing process, and he will instruct participants in the use of these protocols.

This workshop will challenge and stimulate your thinking about who you are and the reality in which you live. It will also offer a view of healing that integrates the psychic and spirit dimensions of the self with the physical, emotional and psychological dimensions.

To learn more or to register, click here.

Venue: The Abbey Hotel, Malvern, Worcestershire WR14 3ET

Date: Monday to Wednesday 24-26 June 2013 9:30 – 17:00 each day

Fees: £456; (Spirit Release Forum Members £438)

Deposit £182 non-members or £174 members to be paid by 31 March 2013

Balance of £274 (non-members) or £264 (members) to be paid by 28 April.

Lunch and Refreshments: Tea, coffee will be provided in morning and afternoon plus a buffet lunch at the hotel.

Accommodation: Accommodation is available in the Abbey Hotel at a reduced rate for delegates of the workshop. Please contact The Abbey Hotel for further information.

Alternatively there is plenty of B&B accommodation in the Malvern area close to the workshop venue. Please contact the local Tourist Board for further information.

Booking: Deposit cheque payments to SRF (Universal) Ltd should be made in full and sent to The Secretary, The Spirit Release Forum, c/o Myrtles, Como Road, Malvern Worcs WR14 2TH

Payment can be made using online banking, through the following details: account owner: SRF (Universal) Ltd.

Account number: 73486818. Sort Code: 20-98-61.

Please add your name and specific course details as a reference.