David S. Ferriero's Blog, page 5

August 10, 2021

The Importance of Acknowledging our History: The Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum, Austin, Texas

This post is part of our ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer our recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

The Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum is located in Austin, Texas, which is situated on the ancestral lands of, among others, the Coahuiltecan, Comanche, Jumano, Lipan Apache, and Tonkawa peoples.

Photo of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum, courtesy of Jay Godwin, LBJ Foundation

Photo of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum, courtesy of Jay Godwin, LBJ FoundationThe modern city of Austin is situated geographically at a crossroads of varied eco-regional types: rich soils and farmland to the east and south, dense forests and grass plains to the north, and the dramatic “hill country” of the Edwards Plateau to the west. As far as our nascent research shows, the indigenous cultures who lived in this area were a similarly diverse mix of cultures who lived on the land and interacted with others in varied and complicated ways. Attempting to document and shine light on this history is difficult but important work, and we are committed to continuing to learn about the land we call home.

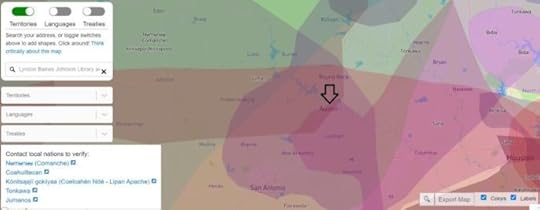

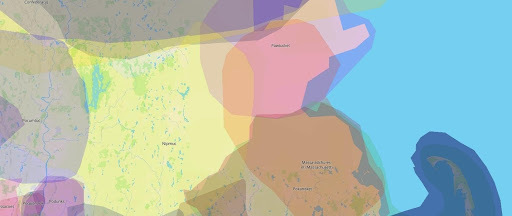

Map of ancestral lands indicating the current location of the Library, from

native-land.ca

Map of ancestral lands indicating the current location of the Library, from

native-land.ca

“The people of this [Tonkawa] tribe were nomadic in their habits in the early historic period, moving their tipi villages according to the wishes of the chiefs of the different bands. They planted a few crops, but were well known as great hunters of buffalo and deer, using bows and arrows and spears for weapons, as well as some firearms secured from early Spanish traders. They became skilled riders and owned many good horses in the eighteenth century. From about 1800, the Tonkawa were allied with the Lipan Apache and were friendly to the Texans and other southern divisions. By 1837, they had for the most part drifted toward the southwestern frontier of Texas and were among the tribes identified in Mexican territory.”

From the Tonkawa Tribe official website.

My thanks to Jenna de Graffenried, Archivist, LBJ Library and Ian Frederick-Rothwell, Archivist, LBJ Foundation, and Jay Godwin, LBJ Foundation, who provided maps, photos and researched the information for this land acknowledgment.

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

Additional information:

Maps:

Native American language cultures map (Perry Castaneda Library, UT Austin): http://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/maps/atlas_texas/ethnolinguistic_natives.jpgTexas Plains, early 1800s map (Perry Castaneda Library, UT Austin): https://texasbeyondhistory.net/forts/images/indiansmap-lg.jpgTexas Indian Lands map (TexasIndians.com): http://www.texasindians.com/themap1.jpgTonkawa and their neighbors in central Texas (TexasIndians.com): http://www.texasindians.com/tonkmap.jpgRecommended readings regarding Native American use of the land on which the LBJ Library is situated:

Anonymous, “Coahuiltecan Indians,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed June 09, 2021, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/coahuiltecan-indians.Jeffrey D. Carlisle, “Apache Indians,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed June 09, 2021, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/apache-indians.Jeffrey D. Carlisle, “Tonkawa Indians,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed June 09, 2021, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/tonkawa-indians.Nancy P. Hickerson, “Jumano Indians,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed June 09, 2021, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/jumano-indians.Lipan Apache Tribe (website), The Lipan Apache Tribe of Texas, accessed June 9, 2021, http://www.lipanapache.org/Communitypages.html.Carol A. Lipscomb, “Comanche Indians,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed June 09, 2021, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/comanche-indians.Texas Beyond History (website), Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, University of Texas at Austin, accessed June 9, 2021, https://texasbeyondhistory.net/index.html.Texas Indians (website), R. Edward Moore and Texarch Associates, accessed June 9, 2021, http://www.texasindians.com/.Research the National Archives’ records on Native American topics at the National Archives website.

More about the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum.

August 6, 2021

The Importance of Acknowledging our History: National Archives Facilities in the Kansas City Area

This post is part of our ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer our recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

The National Archives operates several facilities in the Kansas City area: the National Archives at Kansas City, Missouri; the federal records center in Kansas City, Missouri; the federal records center in Lee’s Summit, Missouri; the federal records center in Lenexa, Kansas; and the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum in Independence, Missouri. All five facilities are situated on the ancestral lands of the Osage and Kansa/Kaw peoples.

National Archives at Kansas City, Missouri, Pershing Road facility

National Archives at Kansas City, Missouri, Pershing Road facilityThe Osage people lived in the Kansas City area long before Europeans explored the area. Artifacts in the area suggest that initial indigenous occupation dates back 10,000 years. The Kansas City Hopewell sites are only a few miles from several local NARA facilities.

Lenexa Federal Records Center, Lenexa, Kansas

Lenexa Federal Records Center, Lenexa, KansasThe Kansa/Kaw peoples also held ancestral lands in the present Kansas City area. “On July 4, 1804, Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery was camped on the site of a Kanza (Kaw) village near the mouth of the Kansas River. They had been told of the proud warriors who inhabited this area, but did not encounter the tribe, who were hunting buffalo in the western part of present-day Kansas.” Kaw Nation Website.

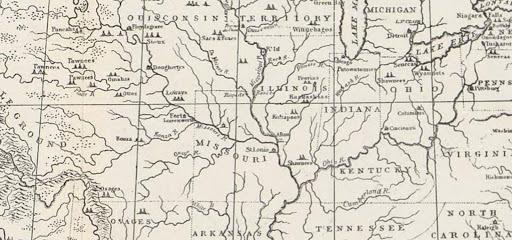

This Lewis and Clark Map from the Library of Congress shows locations of local Native American villages:

Independence area crop:

“The Lewis and Clark expedition had a profound effect upon the Kaw. As people learned about the desirable lands along the Missouri and Kansas Rivers, the Kaws presented a formidable obstacle to westward expansion.” The Kaw Nation website.

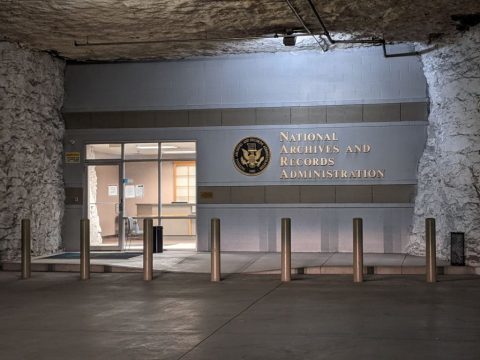

Kansas City Federal Records Center, Subtropolis facility, Kansas City, Missouri

Kansas City Federal Records Center, Subtropolis facility, Kansas City, MissouriIn addition to the Osage and Kansas/Kaw peoples, numerous other tribes, including the Kickapoo, Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandotte, Kaskaskia, also had a presence here at different times.

Map of Indian Tribes of North America, from the State Historical Society of Missouri

Map of Indian Tribes of North America, from the State Historical Society of Missouri Lee’s Summit Federal Records Center, Lee’s Summit, Missouri

Lee’s Summit Federal Records Center, Lee’s Summit, Missouri The Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum, Independence, Missouri

The Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum, Independence, Missouri“The Kickapoo Tribe entered into 10 treaties with the United States government from 1795 to 1854. These treaties brought devastating consequences; the treaties shifted the homelands of the Kickapoos from Illinois to Indiana, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and Mexico.” From the Kansas Kickapoo Tribe website.

George Catlin’s 1896 Map of Indian Country , from the State Historical Society of Missouri.

George Catlin’s 1896 Map of Indian Country , from the State Historical Society of Missouri.My thanks to Sam Rushay, Supervisory Archivist, Truman Presidential Library; Laurie Austin, audiovisual archivist, Truman Presidential Library; Jake Ersland, Director of Archival Operations, National Archives at Kansas City; Tim Rives, Deputy Director of Archival Operations, National Archives at Kansas City; and Kimberlee Ried, Public Affairs Specialist, Museum Programs Division, the National Archives at Kansas City, who researched the information for this land acknowledgment.

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

Additional Resources:

Indians and Archaeology of Missouri by Carl H. and Eleanor F. Chapman (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1983). An Introduction to Kansas Archeology by Waldo R. Wedel (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1959). Prehistoric Man on the Great Plains by Waldo R. Wedel (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, fourth printing, 1974). The End of Indian Kansas by Craig Miner and WIlliam E. Unrau (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1990).Historic Sibley, Missouri website A map of Missouri notes Native American villagesAn Indian Tribes of North America map comes from the State Historical Society of MissouriKansapediaThe IDA Treaties ExplorerFrom the National Archives’ Catalog:

Records Pertaining to Recreation, Land Use, and State Cooperation (archives.gov) File on history and development of Fort Osage State Park and the Osage nation. Trowbridge Hopewell site: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/63819991 Renner-Brenner Hopewell site: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/123865060August 2, 2021

The Importance of Acknowledging Our History: The Washington National Records Center, Suitland, Maryland

This is another post in my ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

The Washington National Records Center in Suitland, Maryland (staff photograph)

The Washington National Records Center in Suitland, Maryland (staff photograph)The National Archives’ Washington National Records Center is located in Suitland, Maryland, which is situated on the ancestral lands of the Nacotchtank peoples, the same peoples who inhabited the lands on which the National Archives in Washington, D.C. now stands.

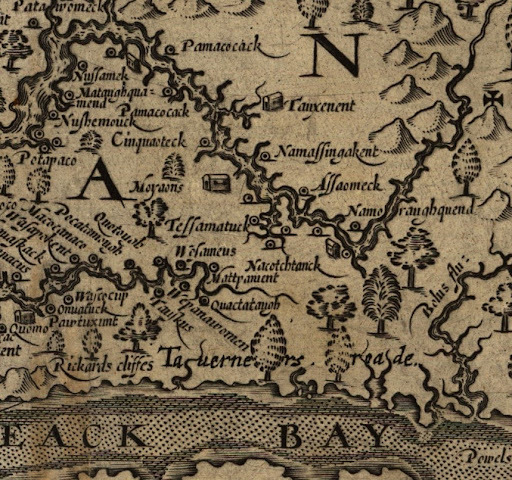

This

1624 map

of the Colony of Virginia held by the Library of Congress takes some adjustment to view – north is to the right. But in this close up, where the Potomac River branches back towards the Chesapeake Bay we see the Nacotchtank noted.

This

1624 map

of the Colony of Virginia held by the Library of Congress takes some adjustment to view – north is to the right. But in this close up, where the Potomac River branches back towards the Chesapeake Bay we see the Nacotchtank noted.The Nacotchtank people were part of the Piscataway Chiefdom, with settlements stretching along the Potomac River. Anacostia is a rendering of the word “Nacotchtank” by English Jesuits. From the American Association of Geographers.

“For thousands of years, until the late sixteenth century, they were sustained by and lived in balance with a verdant, pristine, and generous environment. The region was heavily populated and vibrant with human activity. The people spoke languages that were part of the immense Algonquian language family that reached from the Southeast up the Northeast coast into what is now Canada, across to the Great Lakes and even to some parts of the Great Plains and what is now California. These languages were not mutually intelligible but they bore enough similarities to enable peoples of the Chesapeake region to communicate with one another. The communities were organized under chiefdoms, a sophisticated and multi-layered system of government. They practiced diplomacy and developed political and military alliances. They were deeply spiritual and expressed their religious values and beliefs in cyclical ceremonies and rituals that kept their world in balance. Long before Europeans arrived, Native people developed and participated in widespread trade systems that brought them into contact with people, goods, and ideas from distant places. Although change has always been part of Native American cultures and lives, Chesapeake peoples’ ways of life were destroyed in a relatively brief period of time when contact with Europeans occurred. Confronted with a catastrophic tidal wave of change, they incurred devastating losses and had to summon every ounce of ingenuity and strength to survive. Some were overwhelmed and extinguished, but some remain to tell their stories today.” from We Have a Story to Tell.

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to Cody White, Archivist and Research Services Subject Matter Expert for Native American Related Records, for providing the research for this post, and to Ann Baker, WNRC Administrative Officer, who provided the facility photograph.

For additional information:

A brief history of the Nacotchank peoples is available at the American Association of Geopgraphers website. The Aborigines of the District of Columbia and the Lower Potomac – A Symposium, under the Direction of the Vice President of Section D. Otis T. Mason; W J McGee; Thomas Wilson; S. V. Proudfit; W. H. Holmes; Elmer R. Reynolds; James Mooney. American Anthropologist, Vol. 2, No. 3. (Jul., 1889), pp. 225-268. Joe Heim, 2015. “How a long-dead white supremacist still threatens the future of Virginia’s Indian tribes.” Washington Post, July 1, 2015. We Have a Story to Tell: The Native Peoples of the Chesapeake Region. Teacher Resource, National Museum of the American Indian, 2006.The American Library Association provides a page of links regarding Indigenous Tribes of Washington, D.C.July 30, 2021

The Importance of Acknowledging Our History: The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

This post is part of our ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer our recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

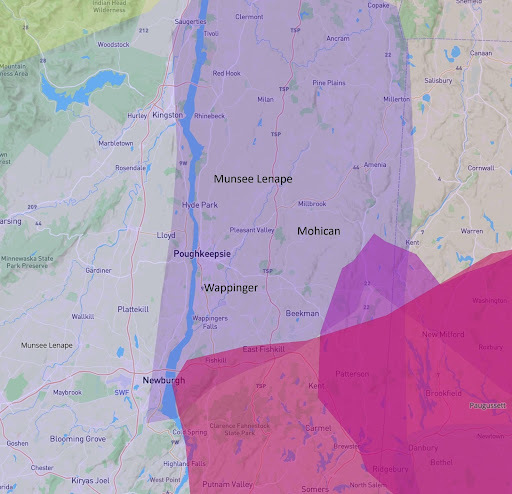

The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum is located in Hyde Park, New York, which is situated on the ancestral lands of Wappinger, Mohican, and Munsee peoples, collectively known as the Lenni Lenape.

The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and MuseumOften referred to as Lenape Munsee, Munsee is sometimes referenced as language and/or a dialect of a larger language family within the Iroquois. It is sometimes used as a tribal distinction within the Lenni Lenape. Likewise, some sources add an “s” to Wappinger, which is now the name of a town in Dutchess County, and some spell “Mohican” as “Mahican.” There were a number of smaller “tribes” or “clans” within the same language family. Land ownership as such wasn’t really a concept as we think of it today or even as the colonists thought of it then. Thus hunting and farming lands overlapped in areas, including ours, as these First Peoples tended to move freely throughout a wide territory unless they were in conflict with another tribe.

Map from:

https://native-land.ca/

Map from:

https://native-land.ca/

There isn’t a clear statement in this area of all tribal names or spellings especially once individual tribes were removed or driven from certain lands. They sometimes re-formed as new groups or legacy groups (Stockbridge Munsee, for example), usually grouped by language but also often by older tribal alliances. The Clearwater land acknowledgement was the basis for the identifiers used here. Our NPS partners in New York reached out to the Stockbridge-Munsee, which was formed by a combination of Munsee speaking local Wappinger and regional Mohican groups after being removed/driven from their traditional lands. Older maps rarely show one tribe in an area and sources note that our area though mostly Wappinger also saw some overlap with other smaller local tribes which inhabited these lands at various times both prior to and after first contact.

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to William A. Harris, Deputy Director, FDR Library, who provided the research for this land acknowledgement.

Additional Resources:

For quick and informative history see the National Park Service’s web page Indigeneous Peoples of this AreaClearwater webpage “Honoring Native Lands”Frederick E. Hoxie, ed., Encyclopedia of North American Indians: Native American History, Culture, and Life from Paleo-Indians to the Present (New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1996).Anton Treuer, Atlas of Indian Nations (Washington DC: National Geographic, 2014).July 26, 2021

The Importance of Acknowledging Our History: The National Archives and Federal Records Center in Denver, Colorado

This is another post in our ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

When completed in 2012, the combined National Archives at Denver and the Denver Federal Records Center facility rested on land largely unchanged by humans. There was some nearby farming, highway and road construction, but no buildings – simply a flat, grass blown prairie with spectacular mountain views.

This 2019 photograph taken by staff shows the National Archives facility in Broomfield, with the Rocky Mountains in the background.

This 2019 photograph taken by staff shows the National Archives facility in Broomfield, with the Rocky Mountains in the background.But the land here was never empty. It has been traversed by dozens of tribal nations over the centuries and was the site of trading, hunting, gathering, and healing. In 1851 a treaty at Fort Laramie formally recognized most of the front range of the Rocky Mountains in present day Colorado as Arapaho and Cheyenne territory. But as was the case throughout the west, gold was soon discovered and both lost yet more territory through new treaties and outright abrogation of others as more and more people moved into the area. The Cheyenne and Arapaho survived these machinations, and outright genocide, and today are a thriving nation in western Oklahoma.

We honor and acknowledge that we are on the traditional territory and ancestral homelands of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Nations, and of those who passed through and took part of the land’s bounty throughout time; the Lakota, Ute, Kiowa, Comanche, Apache, Shoshone, among many others. We respect the many diverse peoples still connected to this land on which we work.

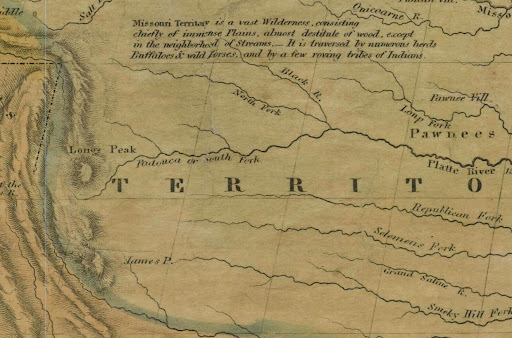

This excerpt from an

1826 map

from the Office of Indian Affairs, today held in our Cartographic branch, shows the area of the present day National Archives at Denver. Longs Peak, today the centerpiece of the Rocky Mountain National Park, lies 60 miles northwest of the facility and the South Fork of the Platte River flows through Denver, 21 miles south of the National Archives at Denver. The mapmaker noted that nomadic tribes called the area home, and the massive Pawnee Empire that spread throughout much of present day Nebraska and Kansas is also marked.

This excerpt from an

1826 map

from the Office of Indian Affairs, today held in our Cartographic branch, shows the area of the present day National Archives at Denver. Longs Peak, today the centerpiece of the Rocky Mountain National Park, lies 60 miles northwest of the facility and the South Fork of the Platte River flows through Denver, 21 miles south of the National Archives at Denver. The mapmaker noted that nomadic tribes called the area home, and the massive Pawnee Empire that spread throughout much of present day Nebraska and Kansas is also marked.The National Archives facility in Broomfield stores, preserves, and makes available Bureau of Indian Affairs records that were created from border to border, 130 years of history for dozens of tribal nations, and available to Native scholars, genealogists, and simply those interested. Through interaction with these records we are especially aware and reminded of this land’s history.

My thanks to Ingi House, Director of Archival Operations, and Cody White, Archivist, both from the National Archives at Denver, who provided information for this land acknowledgement.

Additional resources:

University of Colorado Systemwide Lands Recognition StatementThe Indigenous Digital Archives Treaties ExplorerNative Land map“Treaty between the United States and the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Crow, Assiniboin, Gros Ventre, Madan and Arikara Indians at Fort Laramie, Indian Territory, 9/17/1851” in the National Archives CatalogJuly 20, 2021

The Importance of Acknowledging Our History: NARA’s Facilities in the Atlanta Area

This is another installment of our ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum is located in Atlanta, Georgia, along with two other facilities run by the National Archives: the National Archives at Atlanta, in Morrow, and the Atlanta Federal Records Center, which is located in Ellenwood.

The National Archives at Atlanta

The National Archives at Atlanta The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library

The Jimmy Carter Presidential Library The Atlanta Federal Records Center

The Atlanta Federal Records CenterAll of these National Archives facilities are situated on the ancestral lands of the Muscogee Nation, also known as the Muscogee Creek Nation, a part of the Creek Confederacy.

Map showing the Muskogee Nation.

Map showing the Muskogee Nation.Source: Native Land

“The Muscogee (Creek) people are descendants of a remarkable culture that, before 1500 AD, spanned the entire region known today as the Southeastern United States. Early ancestors of the Muscogee constructed magnificent earthen pyramids along the rivers of this region as part of their elaborate ceremonial complexes. The historic Muscogee, known as Mound builders, later built expansive towns within these same broad river valleys in the present states of Alabama, Georgia, Florida and South Carolina.”

From: MuscogeeNation.com

My thanks to Gwen E. Granados, Director of the National Archives at Riverside, and Christopher Geissler, Deputy Director of the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum, who researched the information for this land acknowledgement.

For more information:

Brief history of the Muscogee people from the Muscogee Nation website.Map showing Creek territory, including the Atlanta Area, situated near the “Chattahoochee River” likely in the general area near the “shallow ford” notation. From: Map by which the Creek Indians gave their statement at Fort Strother on the 22nd Jany, 1816 : [Alabama and Georgia], Library of Congress.“Ratified Indian Treaty 198: Comanche, Wichita, Cherokee, Muscogee, Choctaw, Osage, Seneca, and Quapaw – Camp Holmes, Muscogee Nation – August 24, 1835,” National Archives Catalog.July 7, 2021

The Importance of Acknowledging our History: The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum, and Boyhood Home

This is part of our ongoing series of blog posts that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

Photo of the Eisenhower Presidential Library, U.S. National Archives.

Photo of the Eisenhower Presidential Library, U.S. National Archives.The Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum, and Boyhood Home is located in Abilene, Kansas, which is situated on the ancestral lands of the Kaw Nation, also known as the Kansa or Kanza people.

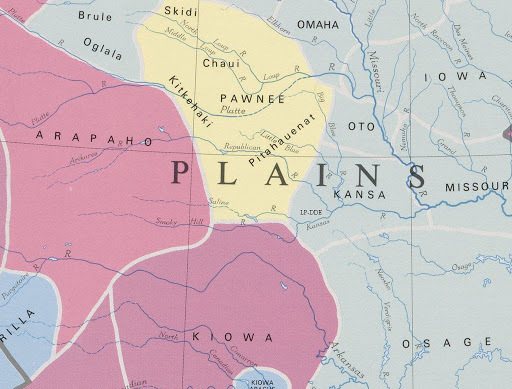

Map with approximate location of the Eisenhower Presidential LIbrary (LP-DDE) noted under the “I” in “PLAINS”,

National Atlas, Indian Tribes, Cultures, and Languages, Department of the Interior

: Geological Survey, Library of Congress.

Map with approximate location of the Eisenhower Presidential LIbrary (LP-DDE) noted under the “I” in “PLAINS”,

National Atlas, Indian Tribes, Cultures, and Languages, Department of the Interior

: Geological Survey, Library of Congress.In 1815, approximately 1,500 members of the Kanza nation were living in 130 earth lodges near the mouth of the Saline River, which is about 25 miles west of Abilene. You can learn more about the long history of the Kanza people on their website. The lands of the Pawnee, Osage, Kiowa, and Sioux tribes were also quite close to the area where the Eisenhower Library now stands.

More information about the Kanza people is available at Kawnation.com.

NARA holds many records that pertain to the Kaw/Kanza/Kansa people, here are just a few:

Ratified Indian Treaty 75: Kansa – St. Louis, October 28, 1815 NAID 83226167 (available online)Ratified Indian Treaty 143A: Documents Accompanying the Message Transmitting the Osage, Kansa and Shawnee Treaties, 1825 (Ratified Indian Treaties 126, 127, and 143) to the 19th Congress NAID 179034069 (available online)History of the Kanza Tribe/Native Flute Music/the Surly Surveyor NAID 26053530Registers of Kaw Families, ca. 1915 – ca. 1915, NAID 2569299Schedules of Allotments to Kaw Indians, 1901 – 1903, NAID 2569314Records of Disposition of Tonkawa and Kaw Allotted Lands, 1914 – 1990, NAID 2569351Records Relating to the Kaw Boarding School, 1886-1904, NAID 1101848 Register of Individual Kaw Accounts, 1927 – 1928, NAID 2570396Have a question about NARA’s records pertaining to the Kaw/Kansa/Kanza Nation? Ask your question on History Hub.

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to Mary Burtloff, Archivist, Eisenhower Presidential Library, who researched the information for this land acknowledgement.

July 1, 2021

Celebrate July 4th with the National Archives!

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress voted to adopt a resolution of independence, declaring the United States independent from Great Britain. On July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was approved.

While John Adams originally recognized July 2, 1776 as “the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America,” he envisioned future celebrations of the event. In a letter to his wife, Abigail Adams, he wrote: “It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward for ever more.”

The National Archives celebrates Independence Day with musical performances, a dramatic reading of the Declaration of Independence, and history-related family activities on July 4th, 2019 in Washington, DC. NARA Photo by Jeffrey Reed.

The National Archives celebrates Independence Day with musical performances, a dramatic reading of the Declaration of Independence, and history-related family activities on July 4th, 2019 in Washington, DC. NARA Photo by Jeffrey Reed.As the trustee of our nation’s founding documents—the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights—the National Archives and Records Administration has a long tradition of celebrating this national holiday in a special way.

This year, the National Archives marks the 245th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence with our traditional Fourth of July program both online and in person!

I will be providing welcoming remarks during the virtual programming, which will also include a variety of educational and family-friendly interactive programs with historical figures and Archives educators, as well as a special production of the traditional reading ceremony. Our in-person celebration will be held on Constitution Avenue and on the steps of the National Archives, complete with re-enactors, family-fun activities, music, and more!All July 4th activities are free and open to the public. See the July 4th schedule to register for a program and download activities and resources. Wherever you are on July 4th, share your celebrations on social media using the hashtag #ArchivesJuly4. Learn more on National Archives News.

Engrossed Declaration of Independence.

National Archives Identifier 1419123

Engrossed Declaration of Independence.

National Archives Identifier 1419123

We can often take for granted our founding documents. I encourage all of us to take time during our Independence Day celebrations to read these documents and to pause and remember the difficult choices our nation’s Founders made and the meaning of these documents today.

Engrossed Declaration of IndependenceConstitution of the United StatesBill of RightsFilm of the transfer of the Charters of Freedom from the Library of Congress to NARAPublic Resolution directing the distribution of certain copies of the Declaration of IndependencePapers of the Continental CongressI wish you all a safe and happy Independence Day!

June 30, 2021

The Importance of Acknowledging our History: The National Archives at Boston and the Boston Federal Records Center

This is another post from our ongoing series of blog posts that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated. I started this series of acknowledgements as a simple way to offer recognition and respect to the people who lived on these lands before us.

Photo of the National Archives at Boston from

https://www.archives.gov/boston

Photo of the National Archives at Boston from

https://www.archives.gov/boston

The National Archives at Boston and the Boston Federal Records Center is located in Waltham, Massachusetts, which is situated on the ancestral lands of the Massachusett and Pawtucket Tribes.

Source: https://native-land.ca/

Source: https://native-land.ca/ The Massachusetts Center for Native American Awareness website notes, “Land Acknowledgements are a simple, powerful way to show respect to the original inhabitants of the land where you are currently standing, presenting, about to engage in an activity, etc. The Massachusetts Center for Native American Awareness (MCNAA) believes that this is a meaningful step toward honoring the truth, making the invisible visible, and correcting the American stories that erase indigenous people’s tribal history and culture. Land Acknowledgements demonstrate a commitment to counter the Doctrine of Discovery and to undo the ongoing legacy of settler colonialism.”

Map from

Greer, A. (2018). Three Zones of Colonization. In Property and Dispossession: Natives, Empires and Land in Early Modern North America (Studies in North American Indian History, pp. 25-238). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Map from

Greer, A. (2018). Three Zones of Colonization. In Property and Dispossession: Natives, Empires and Land in Early Modern North America (Studies in North American Indian History, pp. 25-238). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Map from the Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag

website

.

Map from the Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag

website

.Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to Jason Hiller, Archives Technician, from the National Archives at Boston, who researched the information for this land acknowledgement.

For further information:

Native Land Massachusett

Native Land Pawtucket

Massachusetts Center for Native American

Massachusett Tribal Website

June 22, 2021

Your Experience Matters

The National Archives (NARA) provides a broad range of services to internal and external customers, including researchers, visitors, educators, genealogists, students, veterans, information technologists, federal agencies and more.

Research Room

at the National Archives in Washington, DC

Research Room

at the National Archives in Washington, DCOur records are critical to the American public, but our work to preserve and provide access to the permanent records of the federal government is only effective if we provide you with a good customer experience. Many people think of our iconic research room in Washington D.C. when they think about contacting the National Archives. But the truth is that as the Agency has focused on our strategic goal to Connect with Customers, we provide many paths into the Archives.

Our staff are working together to understand and improve your journey with us, which may start with an email, a phone call, or an online search. You may ask a question on History Hub or download copies of our records from our online Catalog. And as the country slowly reawakens from pandemic times, you may visit one of our Presidential Libraries or research rooms across the country. We know that many of you perform a combination of these tasks and more in the course of working with the Archives. There are so many ways to interact with our agency, and we want to make sure that regardless of the ways you come to NARA, we will support your needs.

Mrs. Laura Bush Attends Helping America’s Youth Event in Atlanta, Georgia. National Archives Identifier 171487285

Mrs. Laura Bush Attends Helping America’s Youth Event in Atlanta, Georgia. National Archives Identifier 171487285In fact, your experience with NARA is one of my highest priorities. It is embedded into the mission of the agency and our strategic goal to connect with customers. I hired the National Archives’ first Chief Customer Experience Officer, Stephanie Bogan, to help us focus as an agency on your experience. I also deputized the Agency’s Management Team to become our Customer Experience Executive Council in order to make customer-focused decisions for the Agency and move us forward.

President Barack Obama Greets Crowd at Hradcany Square. National Archives Identifier 159982183

President Barack Obama Greets Crowd at Hradcany Square. National Archives Identifier 159982183We recently conducted an enterprise-wide assessment to understand:

the agency’s ability to listen to and learn from our internal and external customers the extent to which we evaluate our service from the customer’s perspectiveand most importantly our capacity to act on what we learnWe have identified numerous opportunities to grow. We are now in the process of translating those opportunities into actions aimed at deepening our understanding of you, our customers. With leadership from the top, we are evaluating qualitative and quantitative market research, cultivating and supporting an organizational culture of service excellence, and identifying ways to modernize our operations to improve our service delivery from your perspective.

David S. Ferriero's Blog