David S. Ferriero's Blog, page 3

October 13, 2021

NARA and the International Council on Archives

The National Archives and Records Administration participates in the International Council on Archives (ICA) to share ideas and strategies with our peer national archives around the world, to engage with the global archival profession, and to provide support to archives in countries that are beginning to develop a stronger recordkeeping culture. We’re looking forward to ICA’s 2021 Virtual Conference, “Empowering Knowledge Societies,” to be held October 25–28.

The ICA was established by UNESCO in 1948 after advocacy by the then-Archivist of the United States for the purpose of collaborating on recordkeeping problems in post-World War II Europe. (Read more about ICA’s founding in this 2017 post on International Archives Day, and follow the link to read Archivist of the United States Solon Buck’s 1946 address to the Society of American Archivists, “The Archivist’s ‘One World’” for his influential argument for international collaboration.)

Over the years, the ICA has encompassed additional types of archives and archivists in all parts of the world, becoming a larger and more diverse organization. ICA is organized into regional branches, as well as sections for particular types of archives or materials (religious collections or audio-visual collections, for example). It hosts a Forum of National Archivists for institutions like NARA and for archival associations like the Society of American Archivists (SAA).

Central to ICA’s professional program is the Programme Commission, which coordinates the professional content of the bi-annual conference or congress, the ICA expert groups, and professional projects of the branches and sections.

NARA’s External Affairs Liaison, Meg Phillips, will be taking office in October as ICA’s Vice President for Programmes, a position in which she will manage the Programme Commission. Her new role will ensure even closer ongoing communication between NARA, ICA, and the international archives community.

In addition to Meg’s involvement, NARA’s Deputy Executive for Archival Operations in Research Services, Chris Naylor, has been serving on the ICA Expert Group against Theft, Trafficking, and Tampering, contributing expertise from NARA’s experience in holdings protection and the Archival Recovery Program. These issues and many others are shared by archives all over the world; with an international market in stolen records, it is important for archives to collaborate on solutions.

National archives have also been focusing energy on building new programs and relationships to better serve indigenous communities. Countries such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Norway are developing practices that NARA can learn from as we also strengthen our engagement with communities we have underserved in the past.

In light of our current involvement in ICA, it is interesting to reread then-Archivist Solon Buck’s 1946 description of how a hypothetical future international council on archives might be structured. Buck’s essay was so influential that today’s ICA is recognizable as the same council he advocated for then. We are all grateful for Buck’s vision.

From “The Archivist’s ‘One World’,” by Solon Buck:

The nature of any proposed international archives organization deserves careful consideration. What shall be the basis of representation? If it is to be non-governmental, as seems desirable, the selection of delegates by national governments is ruled out. If there were in each country national associations of archivists such as the Society of American Archivists, these associations might constitute the membership and select the delegations to international meetings. But this is the case in only a few countries. Archival institutions might be members and send their delegates. But this, strictly interpreted, would leave the associations unrepresented as such, might leave out the general archival administrations in certain countries, and certainly would leave out many individuals competent in the field of archives. Some combination seems desirable. Perhaps all archival associations, regional, national, or local, and all archival administrations or institutions, governmental or private, might be members with the right to send voting delegates to formal congresses. I believe that there should also be provision for individual members entitled to receive publications and other literature, to attend meetings, and to participate in other activities. The organization, however, should be something more than an association of individuals speaking only for themselves; it should, I believe, be a genuine international council, with its members speaking for established associations and institutions.

This is a recognizable description of the ICA today.

Although living in the pandemic’s virtual world has been difficult for all of us, the decision to have ICA’s 2021 conference online makes this the easiest year ever to catch up with the latest developments at archives around the world and learn something about ICA. Perhaps we’ll see some of you later in October at ICA’s Virtual Conference, Empowering Knowledge Societies!

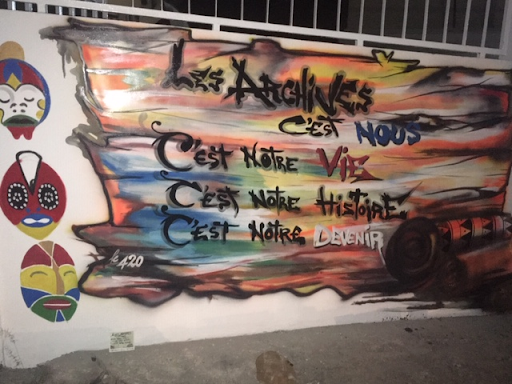

Mural outside the National Archives of Cameroon, which hosted the ICA conference in 2018. (Photo courtesy of Meg Phillips)

Mural outside the National Archives of Cameroon, which hosted the ICA conference in 2018. (Photo courtesy of Meg Phillips)“Les Archives, c’est nous

C’est notre vie

C’est notre histoire

C’est notre devenir”

The archives are us

It’s our life

It’s our history

It’s our future.

October 12, 2021

The Importance of Acknowledging our History

Last April, I wrote a blog post that acknowledged the people who once lived on the land on which NARA’s flagship building is now located. This post was the first of my blog series of acknowledgements that offer recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

The National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C., is situated on the ancestral lands of the

Natcochank peoples.

The National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C., is situated on the ancestral lands of the

Natcochank peoples.

Since then, through this blog, we have toured all of NARA’s facilities across the country. At each site, we asked the simple question of who lived on this land before us. Our staff researched the history and provided information for each facility.

National Archives facilities across the country

National Archives facilities across the country

Land acknowledgments evolve over time as we learn more about our history and our understanding deepens. I offer the following as an initial land acknowledgement for the National Archives and Records Administration:

The National Archives and Records Administration acknowledges that we are located on the ancestral homelands of many Native American peoples across the country.

As the nation’s record keeper, we acknowledge that we have played a role in shaping the histories of local Native Americans by preserving and providing access to the permanent federal records of this county. We recognize, share and celebrate the history of local Native Americans and their immemorial ties to this land.

We commit ourselves to developing deeper partnerships that advocate for the progress, dignity and humanity of the many diverse Native Americans who still live and practice their heritage and traditions on this land today.

GIF is from the

Interactive Time- Lapse Map…

GIF is from the

Interactive Time- Lapse Map…

Heather Miller of the Wyandotte Nation advises, “When you hear or read a land acknowledgment, take some time to think about how you are recognizing the Indigenous community, what you know about it, and if you can’t think of anything, ask yourself why, educate yourself, reach out, connect.”

“Find a way to build a relationship with the Native community,” she says. “Buy a book by a Native author, download music, donate to a cause, learn something about the people who were here before you.” From This Land Was Their Land.

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

For further information:

American University land acknowledgement at: https://www.american.edu/soe/land-acknowledgement.cfm

Decolonizing museums webinar Lively webinar from Illinois State Museum.

A Guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgement

Guide to Indigenous Land and Territorial Acknowledgements for Culture Institutions

Honor Native Land: A Guide and Call to Acknowledgement

Native American records at the National Archives

My sincere appreciation for those who provided research, information, maps and images to support this series of blog posts. Contributors include:

Gwen E. Grenados, Director, the National Archives at Riverside

Christopher Geissler, Deputy Director, the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum

Jason Hiller, Archives Technician, the National Archives at Boston

Robert Kett, Digital Imaging Technician, the Barack Obama Presidential Library

Douglas A. Bicknese, Director of Archival Operations, the National Archives at Chicago

Glenn Longacre, Archivist, the National Archives at Chicago

Leo Belleville, Archivist, the National Archives at Chicago

Jeremy Farmer, Archives Technician, the National Archives at Chicago

Rose Miron, the Director of the D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the Newberry Library in Chicago

Allison Cutuk, Assistant Director, Kingsridge Federal Records Center

Saundra Coleman, Archives Technician, Kingsridge Federal Records Center

Aaron Sipes, Supervisory Archives Specialist, Dayton Federal Records Center

Ingi House, Director of Archival Operations, the National Archives at Denver

Cody White, Archivist, Research Services Subject Matter Expert for Native American Related Records, the National Archives at Denver

Michael Wright, Director of Archival Operations, the National Archives at Fort Worth

Melinda Johnson, Archives Specialist, the National Archives at Fort Worth

Stacey Wiens, Archives Specialist, the National Archives at Fort Worth

Sam Rushay, Supervisory Archivist, the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum

Laurie Austin, Audiovisual Archivist, the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum

Jake Ersland, Director of Archival Operations, the National Archives at Kansas City

Tim Rives, Deputy Director of Archival Operations, the National Archives at Kansas City

Kimberlee Ried, Public Affairs Specialist, Museum Programs Division, the National Archives at Kansas City

Sara Lyons Davis, Education Specialist, the National Archives at New York City

Patrick Connelly, Director of Archival Operations, the National Archives at Philadelphia

Grace Schultz, Archivist, the National Archives at Philadelphia

Anne R. Price, Move Coordinator, the Pittsfield Federal Records Center

Stefanie Hutchins, Chief of Staff, Agency Services

Stephanie Bayless, Director of Archival Operations, the National Archives at San Francisco

John Seamans, Archives Technician, the National Archives at San Francisco

Crystal Shurley, Archival Technician, the National Archives at Seattle

Ann Baker, WNRC Administrative Officer

Spencer Howard, Archives Technician, the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library

William A. Harris, Deputy Director, the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

Mary Burtzloff, Archivist, the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Museum, and Boyhood Home

Rachael MacAskill, Assistant Director, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Maria Quintero, Outreach and Program Manager, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Jenna de Graffenried, Archivist, the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library and Museum

Ian Frederick-Rothwell, Archivist, the LBJ Foundation

Jay Godwin, the LBJ Foundation

Meghan Lee-Parker, Archivist, the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum

Lauren White, Archivist, the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library

Kristin Phillips, Public Affairs Specialist, the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum

Don Holloway, Curator (retired), the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum

Ira Pemstein, Supervisory Archivist, the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum

Aimee Muller, Archivist, the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum

Michael Pinckney, Archivist, the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum

Paul Santa Cruz, Archivist, the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum

Robert Holzweiss, PhD., Deputy Director, the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum

Professor Alston V. Thoms, Director, Archaeological-Ecology Laboratory, Texas A&M University

Kara Ellis, Archivist, the William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum

Adam Bergfeld, Archivist, the William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum

Meredith Doviak, Community Manager, Office of Innovation

Pamela Wright, Chief Innovation Officer, NARA

Previous Blog posts in this series:

Washington, D.C., posted 4/20/2021College Park, MD, posted 5/10/2021Seattle, posted 6/11/2021Hoover Library, posted 6/21/2021Boston, posted 6/30/2021Eisenhower Library, posted 7/7/2021Atlanta/Carter Library, posted 7/20/2021Denver, posted 7/26/2021Roosevelt Library, posted 7/30/2021Suitland, MD, posted 8/2/2021Kansas City, posted 8/6/2021Truman Library, posted 8/6/2021Johnson Library, posted 8/9/2021Ft. Worth, posted 8/13/2021Kennedy Library, posted 8/16/2021Philadelphia, posted 8/20/2021Dayton/Kingsridge, posted 8/24/2021Reagan Library, posted 8/25/2021St. Louis, posted 9/3/2021Riverside, posted 9/7/2021Nixon Library, posted 9/15/2021San Bruno, posted 9/17/2021Ford Library/Museum, posted 9/21/2021New York City, posted 9/23/2021Bush Libraries, posted 9/28/2021Pittsfield, posted 10/1/2021Clinton Library, posted 10/4/2021Chicago/Obama Library, posted 10/5/2021October 5, 2021

Acknowledging our History: NARA’s facilities in Chicago

This post is another in my ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer our recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

The National Archives at Chicago and the Chicago Federal Records Center

The National Archives at Chicago and the Chicago Federal Records CenterThe National Archives at Chicago and the Chicago Federal Records Center in Southwest Chicago, the current location of the Obama Library in the Hoffman Estates, and the future location of the Obama Center at Jackson Park (which will be a privately operated, non-federal organization, but will host a substantial number of items loaned by the National Archives) are all situated on the ancestral lands of several tribal nations: the Council of the Three Fires: the Odawa, Ojibwe Nations and the Potawatomi. This name recognizes that each tribe functions as brethren to serve the alliance as a whole. See Potawatomi Heritage – Encyclopedia: Three Fires Council.

President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama, “Obama breaks ground…”

CNN

President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama, “Obama breaks ground…”

CNN

“The Ojibwe were said to be the Keepers of Tradition. The Odawa were known as the Keepers of the Trade. The Potawatomi were known as the Keepers of the Fire. Over time, the Potawatomi migrated from north of Lakes Huron and Superior to the shores of the mshigmé or Great Lake. This location—in what is now Wisconsin, southern Michigan, northern Indiana, and northern Illinois—is where European explorers in the early 17th century first came upon the Potawatomi; they called themselves Neshnabék, meaning the original or true people” From the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi website.

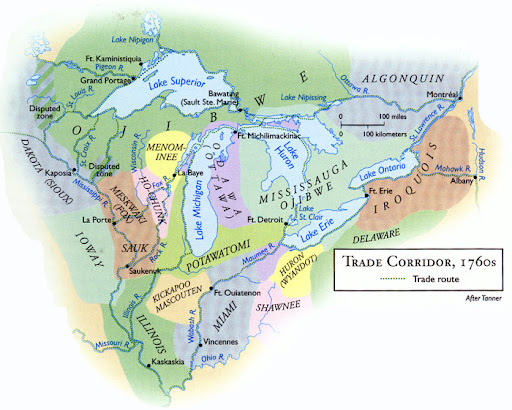

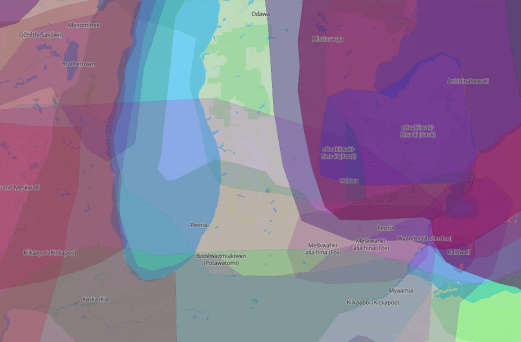

Trade Corridor, 1760s from the

Geography of Michigan webpage

.

Trade Corridor, 1760s from the

Geography of Michigan webpage

.This includes the Illinois Confederacy: the Peoria and Kaskaskia Nations; and the Meskwaki, Myaamia, Thakiwaki, and Wea Nations. The Sauk and Fox called the shores of Lake Michigan home. The Ho-Chunk, Kiikaapoi, Mascouten Nations, and Menominee still call the region of northeast Illinois home.

Section of a

Library of Congress Map

, “Indian land areas judicially established,” 1978,

Section of a

Library of Congress Map

, “Indian land areas judicially established,” 1978, featuring Bodéwadmiké (Potawatomi) land around the Great Lakes, noted in This Land Was Their Land .

Chicago remains the home to one of the largest urban Indigenous communities in the United States.

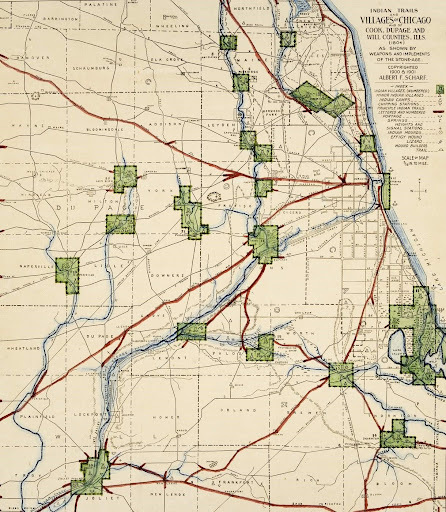

Alfred Scharf’s map of Chicago in 1804, produced in 1901, color version courtesy of the

Chicago History Museum

.

Alfred Scharf’s map of Chicago in 1804, produced in 1901, color version courtesy of the

Chicago History Museum

.Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to Robert Kett, Digital Imaging Technician, Barack Obama Presidential Library, Douglas A Bicknese, Director of Archival Operations, Glenn Longacre, Archivist, and Leo Belleville, Archivist, for providing researching information and providing images for this post. Thanks also to Rose Miron, the Director of the D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the Newberry Library in Chicago, whose assistance is greatly appreciated.

For additional information:

Helen Tanner’s Atlas of Great Lakes Indian History.The Illinois State Museum’s Indian Villages of the Illinois Country Atlas.Many Nations: A Library of Congress Resource Guide For The Study of Indian and Alaska Native Peoples of the United States. Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center websiteAmerican Library Association – Potawatomi of IllinoisHistory of the Potawatomi from the Milwaukee Public MuseumPotawatomis from the Encyclopedia of ChicagoThe Potawatomi of Illinois from AccessGenealogy Video – Illinois State Historical Society History Happy Hour on Native Americans of the Illinois Country (Three Fires Section – 40:43 to 52:41)Barack Obama Presidential Library websiteOctober 4, 2021

Acknowledging our History: The William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum, Little Rock, Arkansas

This post is another in my ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer our recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

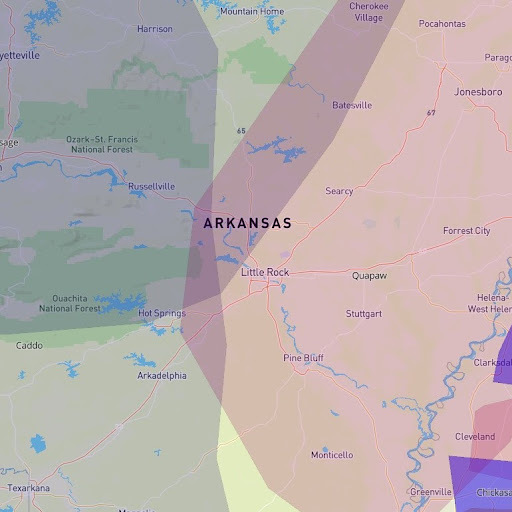

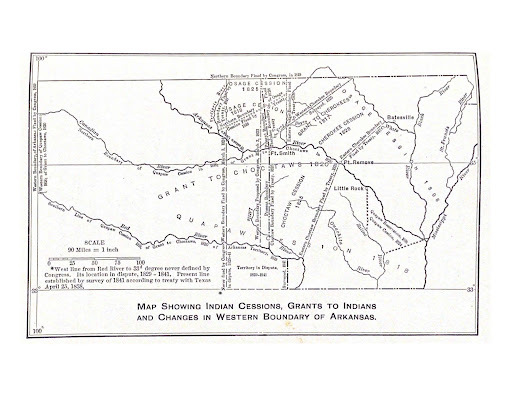

The Clinton Library is located in Little Rock, Arkansas which is situated on the ancestral lands of the Opaxpa (Quapaw) and Osage peoples.

The William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum, courtesy of the Clinton Foundation

The William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum, courtesy of the Clinton FoundationThousands of Muscogee, Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and other indigenous tribes also passed through the area during the Trail of Tears following the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

The Arkansas River Valley was the home of two Dheigha – Sioux tribes, the Ogaxpa, or Quapaw, and the Osage. These nations had originally lived in the Ohio River Valley and migrated to Missouri and Arkansas at some point before Europeans arrived in the region. In 1673, an indigenous tribe in present-day Illinois identified the tribes in the Arkansas River Valley to French explorer Father Jacques Marquette as the “Arkansea,” meaning “people of the south wind.” This name later became associated with the territory and the state.

The site of the William J. Clinton Library and Museum is on land previously claimed by the Quapaw. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Quapaw had a trading relationship with the French. After the Louisiana Purchase, the relationship with white settlers shifted, particularly once the Arkansas territorial capital moved to Little Rock. The treaties of 1818 and 1824 ultimately accomplished the cession of Quapaw lands in Arkansas. Most Quapaw now reside in Oklahoma, with the tribal headquarters in Quapaw, Oklahoma. In 2014, the tribe purchased land near the Little Rock Port Authority because of the suspected presence of tribal remains. The tribe sold the land back to the Port Authority in 2019.

Map from native-land.ca

Map from native-land.caThe Osage primarily resided in southwestern Missouri, but made frequent hunting forays into Arkansas. As Dheigha Sioux, they were similar to the Quapaw linguistically and culturally. While they also held a trading relationship with Spanish and French settlers, they were forced to cede their lands in the treaties of 1808, 1818, and 1825. The Osage now primarily reside in Oklahoma, where the tribal headquarters is located.

After the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, thousands of Native Americans, Black slaves, white spouses, and Christian missionaries passed through Arkansas on what became known as the “Trail of Tears.” Both the group led on military roads by John Bell and the group led over water by Principal Chief John Ross passed through the Little Rock area. Because of the convergence of these two routes, North Little Rock (across the river from the Clinton Library) was the state’s most active site during Indian Removal.

Map of Indian Land Cessions from John Hughs Reynolds, Makers of Arkansas History. (1905) page 296A

Map of Indian Land Cessions from John Hughs Reynolds, Makers of Arkansas History. (1905) page 296A Trail of Tears National Historic Trail marker in North Little Rock, just across the Arkansas River from the Clinton Library. Photo Credit: City of North Little Rock.

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail marker in North Little Rock, just across the Arkansas River from the Clinton Library. Photo Credit: City of North Little Rock.Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to Kara Ellis, Archivist, William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum and Adam Bergfeld, Archivist, William J. Clinton Presidential Library and Museum for providing research and images for this pos t.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris S. The Rumble of a Distant Drum: The Quapaws and Old World Newcomers 1673-1803. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Baird, David W. The Quapaws: A History of the Downstream People. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980.

Bell, James W. “Little Rock (Pulaski County).” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/little-rock-970/ (Accessed 29 September 2021).

Foreman, Grant. Indian Removal: The Emigration of the Five Civilized Tribes. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1953.

Journey of Survival: Indian Removal Through Arkansas. http://journeyofsurvival.org (Accessed 29 September 2021).

Key, Joseph. “Quapaw.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/quapaw-550 (Accessed 29 September 2021).

Osage Nation. http://www.osagenation-nsn.gov (Accessed 29 September 2021).

Peacock, Leslie Newell. “The Quapaw Return to Arkansas.” Arkansas Times. 20 November 2014. https://arktimes.com/news/arkansas-reporter/2014/11/20/the-quapaw-return-to-arkansas (Accessed 29 September 2021).

Quapaw Tribe Official Website. http://quapawtribe.com (Accessed 29 September 2021).

Reynolds, John Hugh. Makers of Arkansas History. New York, Boston etc.: Silver, Burdett and Company, 1905.

Sabo, George, III. “Osage” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/osage-551/ (Accessed 29 September 2021.)

Sloan, Kitty. “Trail of Tears.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/trail-of-tears-2294/ (Accessed 29 September 2021).

Documents from the National Archives’ Online Catalog:

1818 Treaty between the Quapaw and the Government of the United States: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/162880134

1824 Treaty between the Quapaw and the Government of the United States: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/120942046

1818 Treaty between the Osage and the Government of the United States: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/100463729

1825 Treaty between the Osage and the Government of the United States: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/169161530

Trail of Tears National Historic Trail Map: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/33754800

Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009 added Little Rock Trail of Tears Route to the National Historic Trail: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/84286359

October 1, 2021

Acknowledging our History: The Pittsfield Federal Records Center, Pittsfield, Massachusetts

This post is another in my ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer our recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

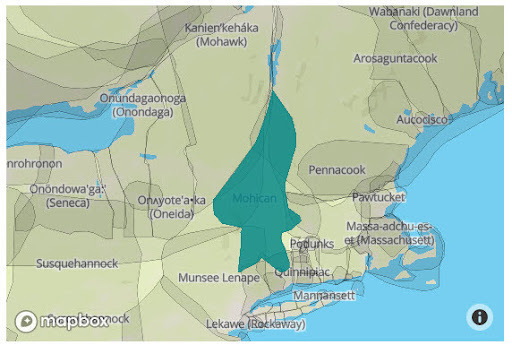

The Pittsfield Federal Records Center is located in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, which is situated on the ancestral lands of the Mohican peoples.

The Pittsfield Federal Records Center, 10 Conte Drive, Pittsfield, MA

The Pittsfield Federal Records Center, 10 Conte Drive, Pittsfield, MA Location of Pittsfield Federal Records Center, Google maps

Location of Pittsfield Federal Records Center, Google maps

Map of ancestral Mohican lands, https://native-land.ca/

Map of ancestral Mohican lands, https://native-land.ca/“Pophnehonnuhwoh, later known as Captain John Konkapot, was born around 1690. He was a member of the Turkey Clan of the Muh-he-con-neok (Mohican) nation. Archeological evidence suggests that his ancestors lived for centuries in what is now known as upstate New York, with lands extending east across the mountains into modern Massachusetts, Vermont, and Connecticut. Up to 30,000 Mohicans lived in widespread communities of longhouses and wigwams before Henry Hudson (c. 1565-1611) sailed his ship up the river that now bears his name into the heart of Mohican territory in 1609. Mohicans greeted the strangers on Hudson’s ship warmly, offering gifts of furs, food, and tobacco. Hudson and his crew reported news of the region’s bountiful natural resources and friendly “River Indians” back to Europe, encouraging more exploration and exploitation. By the time of Konkapot’s birth only 80 years later, the Mohican population was dwindling and destabilized by deadly epidemics, war with the Mohawk for control of the fur trade, and an influx of European colonists.” From Pophnehonnuhwoh (Captain John Konkapot): A Mohican Sachem

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to Anne R. Price, Move Coordinator, Pittsfield Federal Records Center, and Stefanie Hutchins, Chief of Staff, Agency Services for providing information and images for this post.

For additional information:

BerkShares Heroes: The Stockbridge Mohican

The Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohican Indians website

September 29, 2021

Fulbright-National Archives Heritage Science Fellowship

Earlier this year, the National Archives, the State Department, and the Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board formalized a partnership to establish the first-ever Fulbright-National Archives Heritage Science Fellowship.

Together with Marie Royce, then-Assistant Secretary of State for Educational and Cultural Affairs, and Paul Winfree, Chair of the Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board, I signed a memorandum of understanding to support archival science education, conservation, and research. Heritage science is an interdisciplinary field that includes conservation, preservation, cultural heritage, archaeological science, and heritage management. The Fulbright-National Archives Heritage Science Fellowship will connect visiting Fulbright scholars with National Archives leaders to conduct cutting-edge research in the National Archives’ state-of-the-art Preservation Lab to translate theory into practice.

Fulbright Students in Paris.

National Archives Identifier 20006198

Fulbright Students in Paris.

National Archives Identifier 20006198

I am pleased to partner with the State Department and the Fulbright Program, and to welcome our first-ever Fulbright Heritage Science scholar to the National Archives. As the lead U.S. government agency in archival science, research, preservation, and conservation, this initiative is a great way for the National Archives to continue to advance and support collaborative research and academic engagement, and to help shape future leaders from around the world in these fields.

I recently provided the following welcome remarks to the Fulbright Foreign Scholarship Board regarding our first-ever Fulbright Heritage Science scholar to the National Archives:

Greetings from the National Archives’ flagship building in Washington, DC, which sits on the ancestral lands of the Nacotchtank peoples. I’m David Ferriero, Archivist of the United States.

The National Archives is America’s record keeper. We preserve and provide access to the permanently valuable records of the government of the United States of America, Records help the American people: claim rights and entitlements, hold our elected officials accountable for their actions, and document our history as a nation.

We hold billions of records in a variety of formats, including textual records, maps, charts, drawings, photographs, film and video, sound recordings, and electronic records. These records are in a variety of media. We hold parchment documents such as the Declaration of Independence, treaties that expanded the United States, as well as treaties negotiated with Native American tribes. We have film of landing on the moon to audio records of Franklin Roosevelt’s fireside chats and the Watergate tapes. In recent years record formats have expanded to include permanent federal posts on popular social media applications such as Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. These electronic records are the fastest growing records at the National Archives and represent over 500 different formats.

The National Archives has over 40 facilities around the country. There are three main types of facilities: Archives that provide access and house permanently valuable records; Federal Record Centers that serve and store records for agency customers; and Presidential Libraries that provide access to a president’s records and are a museum for that president.

Preservation Programs at the National Archives is responsible for protecting records by minimizing chemical and physical deterioration and damage to the records. Preservation minimizes the loss of information and extends the life of cultural property, which allows long-term access to all formats of permanent records. Preservation Programs is key to the successful delivery of NARA’s core mission: to drive openness, cultivate public participation, and strengthen our nation’s democracy through public access to high-value government records.

The National Archives is committed to the preservation of permanent original records as they provide us with important information about our material culture and give a tangible connection to our history. The size and the dispersed locations of our holdings are challenges for ensuring their preservation. Research, testing, and scientific analysis contribute important data to the development of sustainable and evidence-based preservation strategies.

We are pleased to start this new partnership with the State Department and the Fulbright Program for our first-ever Fulbright Heritage Science scholar to the National Archives. This partnership fosters the National Archives’ Transformational Outcomes to be an agency of leaders and opens our organizational boundaries to learn from others. It also shows the value that the National Archives places on records and cultural heritage to understand ourselves and build connections with others.

Our organizations share the common goals of advancing the interests of the American people and furthering the pursuits of scholarship and research. Our partnership will support scholarship and applied research in archival records preservation and conservation and will bolster international cooperation in this field.

The Fulbright-National Archives Heritage Science Fellowship will connect visiting Fulbright scholars with National Archives leaders to conduct cutting-edge research in the National Archives’ state-of-the-art Preservation Lab to translate theory into practice.

Our goal is for this partnership to foster stronger connections between U.S. and foreign scholars, with archival professionals able to learn from one another, benchmark best practices, and access the vast resources available through the National Archives and Records Administration.

As the lead U.S. government agency in archival science, research, preservation, and conservation, this initiative is a great way for the National Archives to continue to advance and support collaborative research and academic engagement, and to help shape future leaders from around the world in these fields.

Through this partnership, we intend to encourage additional American and international Fulbright Program participants to apply for and affiliate with NARA to create ongoing linkages between Fulbright Program alumni and NARA. The Fellowship will offer one Fulbright Visiting Scholar up to one year of research in the United States to engage in heritage science research, applied heritage science research, or related fields; pair the Fulbright Scholar with one or more NARA preservation scientists who will offer collaboration, training, mentorship, and guidance; and provide an affiliation with NARA’S heritage science research and applied heritage science research.

The work of the Fulbright Scholar will be conducted out of NARA’s preservation lab at the National Archives at College Park in Maryland, as well as remotely, as needed. I want to thank our preservation staff for hosting and collaborating on this prestigious program and commend our Executive for Research Services, Ann Cummings, for her vision and direction that makes this collaboration possible.

The National Archives is committed and perfectly poised to provide Fulbright Visiting Scholars the opportunity to access our vast holdings. We look forward to offering foreign scholars the chance to research in the United States in the fields of archival records preservation and heritage science to gain insightful knowledge and experience that will aid in making historical records available for future generations.

This is the beginning of a beautiful partnership.

Thank you.

Learn more about the Fellowship, including how to apply here: https://cies.org/fulbrightnationalarchives

September 28, 2021

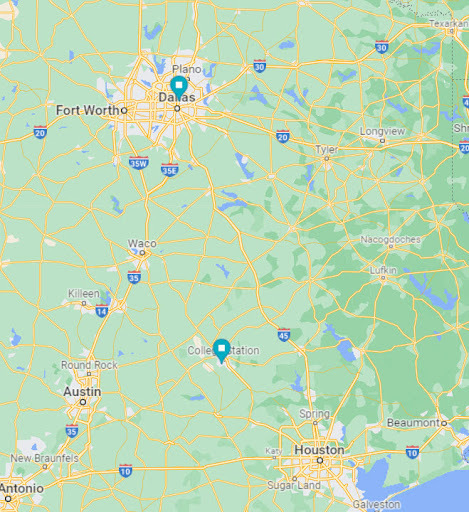

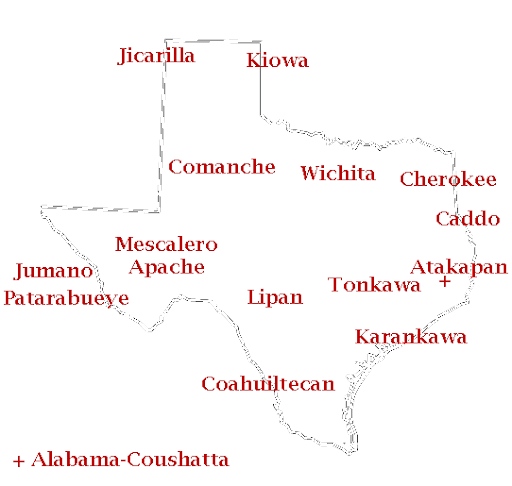

Acknowledging our History: The George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum, Dallas, and the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum, College Station Texas

This post is another in my ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer our recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

Google map, pins indicating the locations of the George Bush Library and Museum in College Station, and the George W. Bush Library and Museum in Dallas, Texas.

Google map, pins indicating the locations of the George Bush Library and Museum in College Station, and the George W. Bush Library and Museum in Dallas, Texas.The George W. Bush Presidential Library, is located in Dallas, Texas, which is situated on the ancestral lands of several Native American tribes, including the Wichita, Caddo, Comanche, Cherokee, Kickapoo, and Tawakoni. The Caddo tribe comprised two dozen related peoples; one of which, the Anadarko, was the most notable group to call the region around Dallas home. Native to Texas, they lived along the Sabine River, but by the 1830s had settled along the Trinity River, which runs northwest to southeast through present-day Dallas County.

Bluebonnets in spring bloom in the Native Texas Park (Photo by Andrew Kaufmann, George W. Bush Presidential Center, Dallas, Texas)

Bluebonnets in spring bloom in the Native Texas Park (Photo by Andrew Kaufmann, George W. Bush Presidential Center, Dallas, Texas)

The Dallas region has been described as a highway that various indigenous peoples used to get from one place to another. The story of the Anadarko people is an example of the movement of Native American peoples from the time of contact with Europeans. The Anadarko people had been settled in the Dallas area for centuries by the time Texas declared independence in 1836. They were forced to move multiple times during the years of the Republic of Texas (1836 – 1846), and the period after Texas was granted statehood. Due to conflict with the Republic, they fled to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) in 1838 – 1839. They returned to Texas several years later and settled along the Brazos River. Increasing white settlement led to their removal to the Brazos Indian Reservation in 1854, and then to Indian Territory in 1859. Many relocated to Kansas during the Civil War, but returned to Oklahoma in the years after the war’s conclusion. Since 1938, the Anadarkos have been part of the Caddo Indian Tribe of Oklahoma.

Photo of the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum, College Station, Texas

Photo of the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum, College Station, TexasThe George Bush Presidential Library and Museum, located in College Station, Texas, is within the Post Oak Savannah, a region that forms the southern boundary between North America’s Great Plains and Eastern Woodlands.

Our staff at the George Bush Presidential Library contacted Professor Alston V. Thoms, Director, Archaeological-Ecology Laboratory, Texas A&M University for information about the indigenous history of the land. Professor Thoms noted “Indigenous hunter-gatherers occupied this vicinity for millennia, including linguistically diverse groups known today as Bidai, Coahuiltecan, Tonkawa, and Wichita. Situated astride an ancient hemispheric travel corridor between agricultural chiefdoms in the Mississippi Valley and those in the Valley of Mexico, this area has long been multicultural. Through the last five centuries, many indigenous groups considered it part of their homeland or use-area, including ancestors of today’s Lipan Apache, Comanche, and Karankawa, as well as the Caddo, other farming groups, and federally non-recognized tribes.”

Map from

Native Americans of Texas

Map from

Native Americans of Texas

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to Paul Santa Cruz, Archivist, from the George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum, Robert Holzweiss, PhD., Deputy Director from the George Bush Presidential Library and Museum, and Professor Alston V. Thoms, Director, Archaeological-Ecology Laboratory, Texas A&M University, for the research, images, and information they provided for this post.

Additional Information:

Carter, Cecile Elkins. Caddo Indians: Where We Come From. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

Gregory, H.F. (ed.). The Southern Caddo: An Anthology. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1986.

Hazel, Michael V. Dallas: A History of Big D. Austin: Texas State Historical Association, 1997.

Smith, F. Todd. The Caddo Indians: Tribes at the Convergence of Empires, 1542-1854. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1995.

Treaty between the United States and the Comanche, Aionai (Hainai), Anadarko, Caddo, et al., Signed at Council Springs, Robinson County, Texas, near the Brazos River, May 15, 1846. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/17551...

Senate’s Advice and Consent to Treaty Ratification with Amendments, February 15, 1847. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/175516197

Instrument of Ratification Signed by President James K. Polk and Secretary of State James Buchanan, March 8, 1847. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/175516195

Native American Relations in Texas, From the Texas State Library and Archives Commission

September 23, 2021

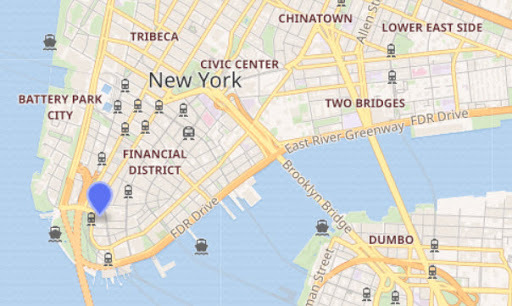

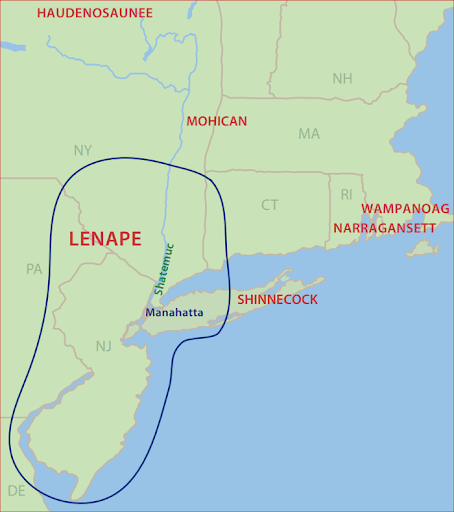

Acknowledging our History: The National Archives at New York City

This post continues my ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer our recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

The National Archives at New York City is located in the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Customs House in New York, New York.

The National Archives at New York City is situated on the ancestral lands of the Munsee Lenape peoples.

Google maps pin location of the National Archives at New York City.

Google maps pin location of the National Archives at New York City.Our staff at the National Archives at New York City found it useful to review land acknowledgement statements from other Manhattan cultural institutions [see examples below] and drafted their own:

We gratefully acknowledge the Native peoples on whose ancestral homelands we gather today. Here at the National Archives at New York City this includes the Munsee Lenape peoples as well as the diverse and vibrant Native communities who reside in the area today.

Access is at the foundation of the National Archives. NARA acknowledges that records held by federal repositories may include documents representative of a history of oppression and attempts at erasure of Native cultures. We strive to empower all Americans to find themselves in our documents and access primary sources to tell their stories, expanding the interpretation of the historical record and the narrative of the United States, moving closer to a more perfect Union.

The National Archives at New York City is located in the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House. We acknowledge that this structure was built roughly upon the site of a Lenape trading area, and later, the original Dutch colonial Fort Amsterdam which was constructed through the use of enslaved labor.

The building stands at the base of Broadway, a thoroughfare that was largely based on an active North/South route across the island of Manhattan that extended to what is now Boston, MA. It was developed and used as a trade route by Northeast Native Communities and later adopted by colonial settlers.

Map from:

Mapping Manhattan: 10 Lenape Sites in New York City

Map from:

Mapping Manhattan: 10 Lenape Sites in New York City

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to Sara Lyons Davis, Education Specialist, from the National Archives at New York City, for the research, photographs, maps and information she provided for this post.

Additional Resources:

On Native Land, Brooklyn Public Library Blog: https://www.bklynlibrary.org/blog/2019/11/08/native-land“The Origin and Meaning of the Name Manhattan” Article from Fall 2010 NYS Historical Association publication; History About Naming of Manhattan with Discussion of Munsee Lenape Communities in the Region: https://repository.si.edu/bitstream/handle/10088/16790/anth_Manhattan.pdf?sequence=1/Manahatta to Manhattan: Native Americans in Lower Manhattan: https://www.k12.wa.us/sites/default/files/public/indianed/tribalsovereignty/elementary/uselementary/uselementary-unit1/level2-materials/manahatta_to_manhattan.pdf Mapping Manahattan: 10 Lenape Sites in New York City: https://www.6sqft.com/mapping-manahatta-10-lenape-sites-in-new-york-city/A Tour of Native New York: https://barnard.edu/news/tour-native-new-yorkTeaching Lenape History: https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/teaching-lenape-history-an-interview-with-pilar-jeffersonAdditional Resources About Land Acknowledgements:

Native Land Guide: https://usdac.us/nativelandNMAI: https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/informational/land-acknowledgementExamples of NY Area Land Acknowledgements:

New Museum Site Heritage Land Acknowledgement: https://www.newmuseum.org/pages/view/building-1 ICP: https://www.icp.org/about/land-acknowledgementNYU Department of History: https://as.nyu.edu/content/nyu-as/as/departments/history/about-us/about-us1.html#:~:text=The%20Department%20of%20History%20at,population%20in%20the%20United%20States.Columbia School of the Arts: https://arts.columbia.edu/about/land-acknowledgementSeptember 21, 2021

Acknowledging our History: The Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Ann Arbor, and the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum, Grand Rapids, Michigan

This post continues my ongoing blog series that acknowledges the ancestral lands on which the National Archives’ buildings are situated across the country. This series of acknowledgements is a simple way to offer our recognition and respect to the people who once lived on these lands.

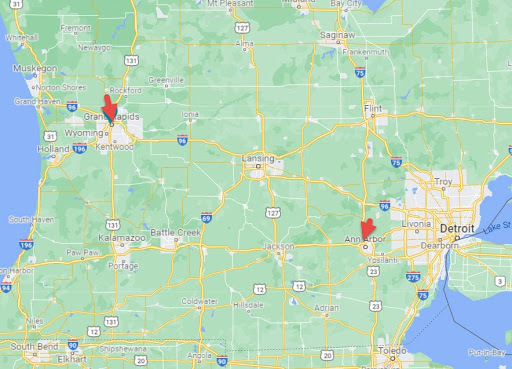

The Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum is located in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library is located in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

From

https://native-land.ca/

From

https://native-land.ca/

The Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, in Ann Arbor, is situated on the ancestral lands of the Anishinaabeg peoples, including the Odawa, Ojibwe, and Potawatomi.

Photograph of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Photograph of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Ann Arbor, MichiganThe Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum, in Grand Rapids, Michigan, is situated on the ancestral lands of the Odawa and Peoria peoples.

Photograph of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum, Grand Rapids, Michigan

Photograph of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum, Grand Rapids, Michigan

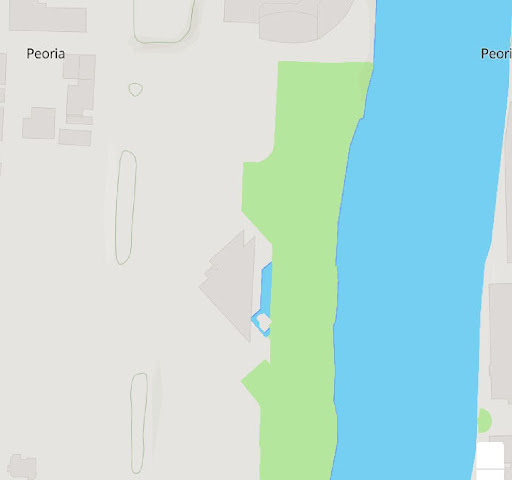

The Museum is the Triangle shape in the picture above from

https://native-land.ca/

The Museum is the Triangle shape in the picture above from

https://native-land.ca/

The park between the museum and the river was first known as Bicentennial Park but had its name changed later to Ah Nab Awen Park. Ah Nab Awen means “resting place”, and the faux burial mounds represent the mound-building culture groups (Hopewell culture) that populated the area during the pre-Columbian period. Actual mounds still can be found along the river bank. The final resting place of President Ford and Betty Ford are opposite the park on the Museum grounds.

The land on which the Museum is situated was later occupied by the Odawa and Peoria peoples. A mill was established as European settlers moved in during the 1830s and 1840s. As the town and industry grew, factories moved to the right bank of the Grand River. That is the arrangement Ford was familiar with in his youth.

Enter your address in this interactive map of Traditional Native Lands to see who once lived where you are now.

My thanks to Lauren White, Archivist, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Kristin Phillips, Public Affairs Specialist, and Don Holloway, Curator (retired), Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum, for the research, photographs, maps and information they provided for this post.

For additional information:

Peoria Tribe: https://peoriatribe.com/culture/ Michigan Odawa History Project: https://turtletalk.blog/resources/grand-traverse-band-history-project/ “Native Americans” LibGuide, Grand Valley State University (with land acknowledgement): https://libguides.gvsu.edu/natamericans/home Tract Books Relating to Kaskaskia, Peoria, Piankeshaw, Wea, and Iowa Trust Lands, 1857: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/2067712Bureau of Indian Affairs Records (Michigan): https://www.archives.gov/research/native-americans/bia-guide/michigan.html Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan. http://www.itcmi.orgFederally Recognized Tribes in Michigan: https://www.michigan.gov/mdhhs/0,5885,7-339-73971_7209-216627–,00.html Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians: https://ltbbodawa-nsn.gov/ Little River Band of Ottawa Indians: https://lrboi-nsn.gov/ Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians: http://www.gtbindians.org/ American Indians at University of Michigan group webpage: http://umich.edu/~aium/about.html The Indians of Washtenaw County, Michigan. 1927 “The Ojibwe,” Michigan State University – Department of Geography, Environment, and Spatial Sciences. https://project.geo.msu.edu/geogmich/ojibwe.html History of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians: https://www.petoskeyarea.com/media/area-history/odawa-indians/ Pokagon Band of Potawatomi: https://www.pokagonband-nsn.gov/ For a Brief History of the Odawa, see https://peoriatribe.com/history/Michigan DNR: Telling Michigan’s Anishinaabe HistorySeptember 20, 2021

Here Rests in Honored Glory: Tomb of the Unknown Soldier Centennial Commemoration

2021 marks the centennial of the creation of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery. On November 11, 1921, President Warren G. Harding officiated interment ceremonies at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

President Harding delivering address in Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery, VA, 11/11/1921

National Archives Identifier 209279977

President Harding delivering address in Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery, VA, 11/11/1921

National Archives Identifier 209279977

In commemoration of this 100th anniversary, the National Archives, in partnership with Arlington National Cemetery, presents virtual programs on September 21 and September 28, 2021. Both programs explore National Archives records related to the cemetery and tomb. A related special document display will open on November 4, 2021, in the National Archives Museum.

Part 1: Here Rests in Honored Glory: National Archives Records Related to Arlington National Cemetery and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Tuesday, September 21, at 3 p.m. (ET)

Features motion picture, cartographic, and photographic records. Timothy Frank, a historian at Arlington National Cemetery, will moderate the discussion with National Archives staff members: Amy Edwards, archivist; Alexandra Geitz, supervisory archivist; and William Wade, supervisory archivist.

Register to attend online. Watch the free program livestreamed on the National Archives YouTube channel.

Part 2: Here Rests in Honored Glory: National Archives Records Related to Arlington National Cemetery and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Tuesday, September 28, at 3 p.m. (ET)

Features textual records. Allison S. Finkelstein, a historian at Arlington National Cemetery, will moderate the discussion with National Archives staff members: John Deeben, archivist; Eric Kilgore, supervisory archives specialist; Lauren Theodore, archives specialist; and Eric Van Slander, archivist.

Register to attend online. Watch the free program livestreamed on the National Archives YouTube channel.

Wreath Laying Ceremony at Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

National Archives Identifier 209280032

Wreath Laying Ceremony at Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

National Archives Identifier 209280032

The 100th Anniversary of Tomb of the Unknown Soldier will be honored with a special display of the Joint Resolution passed by Congress to return to the United States “the body of an American, who lost his life during the World War and whose identity has not been established.” The display opens on November 4, 2021 in the West Rotunda of the National Archives Museum. It will be open with limited capacity 10 a.m–5:30 p.m., daily.

Required: reserve timed entry tickets on Recreation.gov.

Annual Pilgrimage of the Gold Star Mothers, Inc. of New York and nearby states., 9/30/1934.

National Archives Identifier 209280039

Annual Pilgrimage of the Gold Star Mothers, Inc. of New York and nearby states., 9/30/1934.

National Archives Identifier 209280039

2021 marks the centennial of the creation of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery (ANC). ANC is leading the Department of Defense’s official commemoration of this anniversary through a variety of programs, projects, and events. To learn more about these and to find out how you can participate, please visit: www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Tomb100

Learn more on the National Archives Google Arts & Culture exhibit: 100th Anniversary of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

David S. Ferriero's Blog