Gregory A. Fournier's Blog, page 30

December 8, 2015

Detroit's Movie Mavin--Bill Kennedy

Detroit Free Press TV Channel Guide print advertisement from the 1970s.Every Baby-Boomer from Detroit and Windsor remembers who gave us our extensive Hollywood movie education--Bill Kennedy. Bill started announcing on the radio professionally in the 1930s at WWJ - The Detroit News station. His deep voice resonated over the air waves.

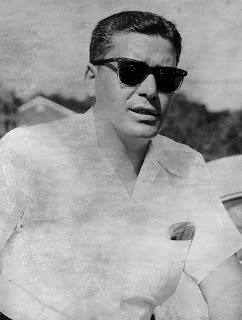

Detroit Free Press TV Channel Guide print advertisement from the 1970s.Every Baby-Boomer from Detroit and Windsor remembers who gave us our extensive Hollywood movie education--Bill Kennedy. Bill started announcing on the radio professionally in the 1930s at WWJ - The Detroit News station. His deep voice resonated over the air waves.In 1940, he embarked on a movie career and signed a contract with Warner Brothers Studios where he worked from 1941 until 1955. Bill had the voice but not the face. He didn't emote well on screen, so he was relegated to a series of flat supporting roles. He played mainly cops, bad guys, radio announcers (no stretch for Bill), newspaper men, and swindlers. In all, Bill Kennedy has 103 film credits.

In the post World War Two era, Kennedy appeared on numerous B-Western television shows including The Lone Ranger, The Cisco Kid, and The Gene Autry Show. Kennedy always spoke kindly of Gene Autry. Bill was over six feet tall and many of Hollywood's leading men were short and didn't like doing fight scenes with him. Gene Autry was short, but always had a job for Bill when he needed it. Autry told him once, "I like beating up bad guys on screen who are bigger than me."

Bill Kennedy playing a newscaster in a Superman episode.

Bill Kennedy playing a newscaster in a Superman episode.What many of us in Detroit know that most people don't is Bill's was the voice behind the opening credits of The Adventures of Superman--one of the most iconic introductions in television history. Bill received a one-time check for $350. He regretted not asking for screen credit which might have benefited his career. The show has been continuously running in syndication since 1952. A link to the Superman program opening is below.

In 1956, Bill Kennedy returned to the Detroit area to host an afternoon movie program called Bill Kennedy's Showtime, for CKLW-TV across the Detroit River in Windsor, Ontario. The show became a big hit. Bill talked about his jaded experiences in Hollywood's heyday and how he worked with many of the top stars. His deadpan delivery and sarcastic wit won the loyalty of viewers. He had an avuncular, self-deprecating manner--especially if talking about a film he was in. If the movie was bad, he would tell his audience.

The show opened with a tight shot on a picture of a woman smoking a cigarette with Bill's theme song Just in Time playing in the background. The photograph was from a magazine. I can see the model in my mind's eye with her elbows on a table and a smoldering cigarette in her right hand. Bill chose the theme song because his professional life was at a low point when he got the job with CKLW.

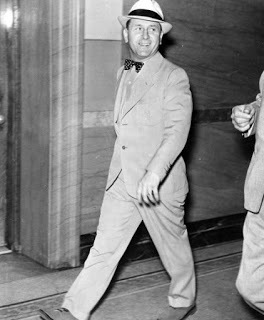

Bill wearing a hat to cover up his hair transplant surgery.In 1969, Bill took his show to WKBD which broadcast out of Southfield, Michigan. The show remained essentially the same with a title change to Bill Kennedy at the Movies. Bill would interview celebrities when they were in Detroit and he took on-air phone calls which were sometimes more interesting than the movies. I enjoyed the live TV commercial pitches of Abe Schroe for his furniture upholstery business.

Bill wearing a hat to cover up his hair transplant surgery.In 1969, Bill took his show to WKBD which broadcast out of Southfield, Michigan. The show remained essentially the same with a title change to Bill Kennedy at the Movies. Bill would interview celebrities when they were in Detroit and he took on-air phone calls which were sometimes more interesting than the movies. I enjoyed the live TV commercial pitches of Abe Schroe for his furniture upholstery business.Abe and Bill always had lively repartee like they knew each other well outside of work. These two got along so well on air that it strikes me Bill was probably part-owner or an investor in Artistic Upholstery. Bill would take a break and Abe would go into his pitch. Nobody else made live commercials on Bill's show--not Ollie Fretter--not even Mr. Belvedere (Detroit inside joke).

In 1983, Bill retired to Palm Beach, Florida. He died of emphysema on January 27, 1997, at the age of eighty-eight. Rest in peace "young, old-timer."

The Adventures of Superman introduction: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q2l4bz1FT8U

Published on December 08, 2015 06:48

December 1, 2015

Henry Ford's Tough Guy--Harry Bennett

Harry BennettHarry Herbert Bennett was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan on January 17, 1892. At the age of seventeen, he joined the United States Navy where he learned the pugilistic arts and became a champion lightweight boxer fighting under the name of Sailor Reese.

Harry BennettHarry Herbert Bennett was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan on January 17, 1892. At the age of seventeen, he joined the United States Navy where he learned the pugilistic arts and became a champion lightweight boxer fighting under the name of Sailor Reese.Legend has it that sometime in 1916, New York newspaper columnist Arthur Brisbane introduced the twenty-four year-old Bennett to Henry Ford. Brisbane witnessed a street brawl where Bennett came to the defense of a fellow sailor under attack by some local thugs. The naval boxing champion acquitted himself well. When the police arrived, they were going to arrest Bennett, but the newspaper man vouched for the young sailor and he was released.

Brisbane told the young tough he had someone he wanted him to meet. Brisbane was writing an article about Henry Ford for the Hearst newspaper chain while Ford was in New York. They met in Ford's hotel room. Kidnapping wealthy people was on the rise in America and Henry Ford was concerned for the safety of his family. Ford was fascinated hearing about the street brawl Bennett was just in. He asked Bennett if he could handle a gun. He could. Upon the young sailor's discharge from the Navy, Bennett was hired at the Highland Park Ford plant in the art department.

Red-haired Harry Bennett was five feet, six inches tall--built like a fire hydrant and just as strong. He cultivated his tough guy image by wearing a fedora, a hand gun, and a bow tie. People who knew him said he was fearless. With no background in engineering or the automobile business, Bennett rose in five years to become head of Ford's infamous Service Department. He was known within the company as the old man's hatchet man.

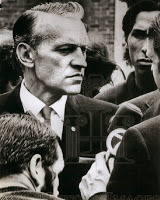

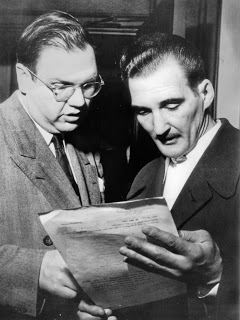

Battle of the Overpass reaching flash point.The Battle of the Overpass outside the Ford Rouge plant was a defining moment for Harry Bennett and the United Auto Workers (UAW). On May 26, 1937, Walter Reuther, Richard Frankensteen, among other union organizers, were beaten by Ford Service men and dragged and kicked down two flights of steel and concrete stairs. The attack was captured by a Detroit News staff photographer. The next day, newspapers around the world ran the photographs and the story. Overnight, Walter Reuther became the most recognized labor leader in America.

Battle of the Overpass reaching flash point.The Battle of the Overpass outside the Ford Rouge plant was a defining moment for Harry Bennett and the United Auto Workers (UAW). On May 26, 1937, Walter Reuther, Richard Frankensteen, among other union organizers, were beaten by Ford Service men and dragged and kicked down two flights of steel and concrete stairs. The attack was captured by a Detroit News staff photographer. The next day, newspapers around the world ran the photographs and the story. Overnight, Walter Reuther became the most recognized labor leader in America. Walter Reuther and Richard Frankensteen

Walter Reuther and Richard FrankensteenAt a National Labor Relations Board hearing held in the summer of 1937, UAW field-organizer Frankensteen testified how Ford's security force assaulted him and Walter Reuther. The labor board found the Ford Service Department had underworld connections with the local Black Hand--a Sicilian gang, and the Dearborn police stood by while the labor demonstrators were beaten. No charges were ever filed.

In 1941, the four-year bloody conflict resulted in the Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo) recognizing the UAW and negotiating their first contract. The Ford executive to sign the contract--Harry Bennett. But this was the beginning of the end of Bennett's tenure with the automotive giant. Henry Ford's wife Clara had as much to do with the contract settlement as anyone. Ford family history notes she threatened to divorce her husband if the labor violence wasn't ended and the contract settled.

Henry Ford IIBy 1945, the old man's health and mental state were declining as Bennett maneuvered to gain control of the company. Clara and her son Edsel's widow--Eleanor Clay-Ford--insisted the company remain under family control. Eleanor threatened to sell her stock if her son was not made president. On September 20th, Henry Ford I officially resigned the presidency and nominated his grandson Henry Ford II to replace him. The Board of Directors rubber-stamped the recommendation. Twenty-eight-year-old Henry Ford II was discharged from active duty with the United States Navy to man the helm of his grand sire's company.

Henry Ford IIBy 1945, the old man's health and mental state were declining as Bennett maneuvered to gain control of the company. Clara and her son Edsel's widow--Eleanor Clay-Ford--insisted the company remain under family control. Eleanor threatened to sell her stock if her son was not made president. On September 20th, Henry Ford I officially resigned the presidency and nominated his grandson Henry Ford II to replace him. The Board of Directors rubber-stamped the recommendation. Twenty-eight-year-old Henry Ford II was discharged from active duty with the United States Navy to man the helm of his grand sire's company.Henry's first official act was to fire Harry Bennett. He drove to the Ford Administration Building on Schaefer Road and walked down to the secluded basement office of his late father's nemesis. But Bennett could see the writing on the wall. It was written in dark blue and read Ford.

The former boxer could not resist giving the young Ford a parting shot. "You're taking over a billion dollar organization here that you haven't contributed a thing to?" The rest of the afternoon, the basement was filled with smoke as Bennett burned his records--almost thirty years of company history--the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Henry Ford ILater that evening, Henry II drove to his grandfather's estate and told him he fired Bennett. The elder Ford's reaction was understated. He simply remarked, "Now Harry is back where he started."

Henry Ford ILater that evening, Henry II drove to his grandfather's estate and told him he fired Bennett. The elder Ford's reaction was understated. He simply remarked, "Now Harry is back where he started." After his loss of power, Bennett retired to an 800 acre wilderness area outside Desert Springs, California. His last moment in the public spotlight came when he was called to testify in the Kefauver Senate Crime Investigation Committee Hearings in 1951.

In 1973, Bennett suffered a stroke. In 1975, he entered the Beverly Manor Nursing Home in Los Gatos, California. On January 4, 1979, he died. His death went unreported for a week--the cause was never released to the public.

http://fornology.blogspot.com/2015/10/walter-p-reuther-assassination-attempt.html

Published on December 01, 2015 05:19

November 23, 2015

John F. Kennedy's Beacon Extinguished Fifty-Two Years Ago

JFK in Ypsilanti. Photo courtesy of Susan Wolter-BrownOn October 20, 1960, presidential candidate John F. Kennedy's motorcade was stopped at about 1:10 AM by Eastern Michigan University students who jammed West Cross Street in front of McKinny Student Union. Kennedy was on his way to a political rally in Ann Arbor the following day.

JFK in Ypsilanti. Photo courtesy of Susan Wolter-BrownOn October 20, 1960, presidential candidate John F. Kennedy's motorcade was stopped at about 1:10 AM by Eastern Michigan University students who jammed West Cross Street in front of McKinny Student Union. Kennedy was on his way to a political rally in Ann Arbor the following day.He made a two or three minute speech telling the cheering crowd of students that he stood "for the oldest party in years, but the youngest party in ideas." Because of the late hour, the soon-to-be president asked to be excused explaining he had a difficult schedule planned for the next day.

In his inaugural speech on January 20, 1960, the new president boldly stated that "a torch has been passed to a new generation." Three years later, on Friday, November 22, 1963, at 11:30 AM, an assassin's bullet cut down President Kennedy in Dallas, Texas while he was campaigning for a second term. He was pronounced dead on the operating table thirty minutes later.

In his inaugural speech on January 20, 1960, the new president boldly stated that "a torch has been passed to a new generation." Three years later, on Friday, November 22, 1963, at 11:30 AM, an assassin's bullet cut down President Kennedy in Dallas, Texas while he was campaigning for a second term. He was pronounced dead on the operating table thirty minutes later.At 1:00 PM, the intercom system at Allen Park High School broadcast the sound of Walter Cronkite announcing John F. Kennedy, thirty-fifth president of the United States, had been assassinated--then he paused. The principal came on and asked for a moment of silence.

I was in sophomore biology class. The shocked silence was punctuated first by whimpering and then open sobbing. This was a defining moment for an entire generation. A mourning wind swept over the nation and the world held its breath.

After two years, ten months, two days, and sixty-nine minutes, Kennedy's torch of optimism was extinguished. But his challenge to America had been met--putting a man on the moon before the end of the decade. The technical breakthroughs from that achievement still benefit mankind.

Published on November 23, 2015 16:28

November 12, 2015

The John Norman Collins Reward Money Shell Game

The third of four composite drawings.On the day of John Norman Collins' sentencing for the murder of Karen Sue Beineman--August 28, 1970--The Ypsilanti Press reported rewards for information leading to the arrest of the killer or killers of seven women in the Ypsilanti/Ann Arbor area had reached $43,500. The rewards came from a variety of sources--each with its own conditions for pay out.$14,000 - The Detroit News offered $2,000 in each of the unsolved murder cases that plagued Washtenaw County from July of 1967 through July of 1969.$7,500 from the Ann Arbor City Council for Police Chief Walter E. Krasney’s discretionary use. Most of the money went into overtime for detectives. $5,000 from the Ypsilanti City Council--which was no longer available. $5,500 raised by The Eastern Echo--Eastern Michigan University's campus newspaper--still available. $1,000 offered by The Ypsilanti Press, and $1,000 donated by Ypsilanti Savings Bank, could only be claimed by persons going through The Ypsi Press. The University of Michigan offered a $7,500 reward for the arrest of Alice Kalom’s killer--but not for the other victims.$2,000 was set aside by The Washtenaw County Board of Supervisors for the capture and conviction of the unknown killer.

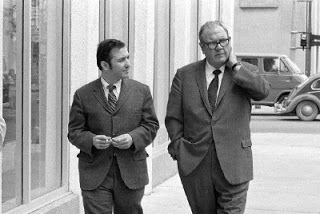

The third of four composite drawings.On the day of John Norman Collins' sentencing for the murder of Karen Sue Beineman--August 28, 1970--The Ypsilanti Press reported rewards for information leading to the arrest of the killer or killers of seven women in the Ypsilanti/Ann Arbor area had reached $43,500. The rewards came from a variety of sources--each with its own conditions for pay out.$14,000 - The Detroit News offered $2,000 in each of the unsolved murder cases that plagued Washtenaw County from July of 1967 through July of 1969.$7,500 from the Ann Arbor City Council for Police Chief Walter E. Krasney’s discretionary use. Most of the money went into overtime for detectives. $5,000 from the Ypsilanti City Council--which was no longer available. $5,500 raised by The Eastern Echo--Eastern Michigan University's campus newspaper--still available. $1,000 offered by The Ypsilanti Press, and $1,000 donated by Ypsilanti Savings Bank, could only be claimed by persons going through The Ypsi Press. The University of Michigan offered a $7,500 reward for the arrest of Alice Kalom’s killer--but not for the other victims.$2,000 was set aside by The Washtenaw County Board of Supervisors for the capture and conviction of the unknown killer. Prosecutor William DelheyWhen questioned by the press the day before Collins was sentenced, Prosecutor William Delhey said, “If there is one person who triggered the events which led to the arrest of Collins, it was Eastern Michigan University Police Officer Larry Mathewson. I have to give a great deal of credit to Mathewson.” High praise indeed for a rookie cop on a university police force who used an old-fashioned police technique--he followed a hunch and started knocking on doors. Delhey was clearly grateful.

Prosecutor William DelheyWhen questioned by the press the day before Collins was sentenced, Prosecutor William Delhey said, “If there is one person who triggered the events which led to the arrest of Collins, it was Eastern Michigan University Police Officer Larry Mathewson. I have to give a great deal of credit to Mathewson.” High praise indeed for a rookie cop on a university police force who used an old-fashioned police technique--he followed a hunch and started knocking on doors. Delhey was clearly grateful. Patricia Spaulding and Diane Joan GosheDuring the cross-examination of Mrs. Diane Joan Goshe, one of the two women who identified Collins driving away with Miss Beineman on the motorcycle, defense attorneys badgered her about the reward money. On the stand, Goshe said she had not given any thought to claiming the reward and "hadn’t really checked into it."

Patricia Spaulding and Diane Joan GosheDuring the cross-examination of Mrs. Diane Joan Goshe, one of the two women who identified Collins driving away with Miss Beineman on the motorcycle, defense attorneys badgered her about the reward money. On the stand, Goshe said she had not given any thought to claiming the reward and "hadn’t really checked into it."Ann Arbor News reporter William Treml wrote that the “most eligible” persons for the reward were the two wig shop ladies—Diane Joan Goshe and Patricia Spaulding—whose eyewitness accounts linked Collins with Beineman. “Without their testimony, it is doubtful the prosecution would have obtained a conviction.”

Collins defense lawyers--Neil Fink and Joseph LouisellThe defense team of Joseph Louisell and Neil Fink tried to plant the impression in the minds of the jurors that the reward money was their key motive for testifying. At one point, Fink asked Mrs. Spaulding if it was not true she and Mrs. Goshe discussed dividing up the reward. Mrs. Spaulding answered emphatically, “No!”

Collins defense lawyers--Neil Fink and Joseph LouisellThe defense team of Joseph Louisell and Neil Fink tried to plant the impression in the minds of the jurors that the reward money was their key motive for testifying. At one point, Fink asked Mrs. Spaulding if it was not true she and Mrs. Goshe discussed dividing up the reward. Mrs. Spaulding answered emphatically, “No!”On December 19, 1970, The Ann Arbor Newsreported Mrs. Goshe had hired the law firm of Keyes, Creal, and Hurbis, to mail letters of inquiry to several public agencies offering reward money. William Delhey ordered an investigation into the status of the reward money. When it was all added up, the conviction reward was small for the Beineman murder. Most of the original offers were no longer available because of restrictions placed by each organization on the reward. Collins was not charged with the other deaths for which the money was set aside.

On February 16, 1971, the Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners recommended the denial of Mrs. Goshe’s claim for the $2,000 the county offered. Writing the legal opinion for the committee, Prosecutor Delhey noted “the reward was offered June 3, 1969, for evidence leading to the conviction for any of the slaying victims of young women committed up to then. Mrs. Goshe testified on the murder of Karen Sue Beineman, and that case came about a month and a half after the reward was offered. Thus, her testimony did not result in any convictions for the still unsolved five murders that preceded the reward offer.

John Norman CollinsDelhey added, “Even if the murder of Miss Beineman was included in the reward offer, the evidence that led to the conviction of Collins came to light through the work of Eastern Michigan University Policeman Larry Mathewson.”

John Norman CollinsDelhey added, “Even if the murder of Miss Beineman was included in the reward offer, the evidence that led to the conviction of Collins came to light through the work of Eastern Michigan University Policeman Larry Mathewson.”Ironically, the women whose testimony helped Delhey win the biggest case of his career were cut out of the reward money by his recommendation. Mathewson was also ineligible for the reward because he was a member of law enforcement and on the public payroll at the time.

Mrs. Goshe was portrayed by the press as trying to profit from the misery of the Beineman family, but she and Patricia Spaulding bravely stood up, cooperated with police, and testified in open court. Both ladies performed laudable public service and came forward when others who knew things did not.

And what was Mrs. Goshe’s reward for sticking her neck out? The defense team publicly dissected her private life revealing a family secret that had nothing to do with the trial and did nothing but hurt a mother and her twelve-year-old son. She was not married to the boy's father. No good deed goes unpunished.

Published on November 12, 2015 03:25

November 3, 2015

The Edmund Fitzgerald Sinking--40th Anniversary

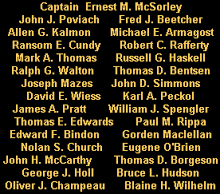

November 10, 2015, marks forty years since all twenty-nine crew members went down with their ship--the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald. The largest of the Great Lakes ore freighters at the time of her sinking, she was dubbed "The Queen of the Great Lakes." The ship was 729 feet long, 39 feet high, and 75 feet wide.

The S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald was loaded in Superior, Wisconsin with 26,000 tons of taconite (iron pellets) headed for the ore docks of Zug Island--just south of Detroit. Winds over 45 knots (50 mph) and waves over 30 feet caused the ship to roll heavily. The captain made a call to another ore freighter saying they had taken on some water but were holding their own. That was just before the ship went off U.S. Coast Guard radar. The pride of the Great Lakes broke in two and sank 530 feet into Lake Superior's Canadian waters--only seventeen miles from protected Whitefish Bay.

The S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald was loaded in Superior, Wisconsin with 26,000 tons of taconite (iron pellets) headed for the ore docks of Zug Island--just south of Detroit. Winds over 45 knots (50 mph) and waves over 30 feet caused the ship to roll heavily. The captain made a call to another ore freighter saying they had taken on some water but were holding their own. That was just before the ship went off U.S. Coast Guard radar. The pride of the Great Lakes broke in two and sank 530 feet into Lake Superior's Canadian waters--only seventeen miles from protected Whitefish Bay. Since the submerged giant sank on November 10, 1975, there have been three underwater expeditions--in 1989, 1994, and 1995. At the request of the families who lost their loved ones, the Canadian government recovered the 200 pound brass bell from the deck of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald on July 4, 1995, and presented it to the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society.

Since the submerged giant sank on November 10, 1975, there have been three underwater expeditions--in 1989, 1994, and 1995. At the request of the families who lost their loved ones, the Canadian government recovered the 200 pound brass bell from the deck of the S.S. Edmund Fitzgerald on July 4, 1995, and presented it to the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society.Today, the bell is displayed at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Whitefish Point, Michigan. Every November 10th at 7:10 PM, the bell is tolled twenty-nine times to honor the Fitzgerald's crew and a thirtieth time to commemorate the estimated 30,000 people and 6,000 ships lost in the Great Lakes.

Gordon Lightfoot's The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald with documentary footage: https://youtu.be/hgI8bta-7aw

Published on November 03, 2015 06:32

October 18, 2015

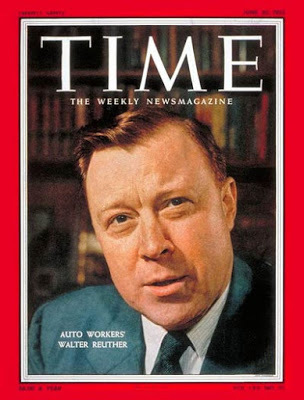

Walter P. Reuther Assassination Attempt Foiled

Walter P. Reuther, recently re-elected to a second term as United Automobile Workers (UAW) president, lived with his wife May and their two small daughters in a modest ranch house on Appoline Street in Detroit, just south of Eight Mile Road.

In his 2013 book Built in Detroit: A Story of the UAW, a Company, and a Gangster, Bob Morris recounts the evening of April 20, 1948. After coming home late from a UAW meeting, Reuther prepared to eat his warmed-over dinner. He was opening the refrigerator door to get some peaches when he turned to answer a question from his wife and survived a 12 gauge shotgun blast through the kitchen window.

Four lead pellets lodged in his right arm, one in his chest, and the rest hit the kitchen cabinets. Reuther was taken to New Grace Hospital where doctors told him he might lose his arm. The labor leader was determined to save it. By working tirelessly at painful physical therapy, he was able to regain limited use of his arm. For the rest of his life, neither Reuther nor his family were without UAW bodyguards and traveled everywhere in an armored Packard.

The attempt on Reuther's life was not an isolated incident of industrial violence. Thirteen months later, Walter's brother Victor, met a similar fate. Bob Morris writes, "Late on the evening of May 24, Victor was reading in his living room when a shot gun blast blew threw his front living room window. The shotgun pellets ripped through the right side of his face and upper body tearing out his right eye."

Victor and Walter Reuther shaking hands left-handed with brother Roy between them.

Victor and Walter Reuther shaking hands left-handed with brother Roy between them.At first the Detroit police dismissed the botched murder attempt of Walter Reuther as a power struggle among union Communists. The Red Scare was a popular and convenient scapegoat for corporate America and made good copy for the post-war press. A Detroit detective said, "Gamblers and crime syndicates have nothing to do with this. It's Communists."

But investigators began hearing underworld connections might be involved. Within five days of Reuther being shot, Detroit police--acting on a telephone tip--brought former vice-president of Ford UAW Local 400, Carl E. Bolton, in for questioning. He was charged with intent to commit murder.

Joseph W. Louisell and Carl. E. BoltonJoseph W. Louisell, Detroit attorney known for defending suspected mob figures, argued Bolton had an alibi and was not at the scene of the crime. After three days in jail, Bolton was released and prosecutors dropped the charges. Bolton was free but still under suspicion.

Joseph W. Louisell and Carl. E. BoltonJoseph W. Louisell, Detroit attorney known for defending suspected mob figures, argued Bolton had an alibi and was not at the scene of the crime. After three days in jail, Bolton was released and prosecutors dropped the charges. Bolton was free but still under suspicion.During the Senator Kefauver Organized Crime Committee hearings (1951-1952), testimony suggested Walter Reuther ran afoul of the Detroit underworld.

Before the shooting, Reuther was aware a Sicilian gang, led by Santo Perrone, was acting as a strike-breaking agency for Detroit companies--big and small. Author Nelson Lichtenstein writes in The Most Dangerous Man In Detroit: Walter Reuther and the Fate of American Labor, "Reuther's assailants were paid by Santo 'the Shark' Perrone, an illiterate but powerful Sicilian gangster." The mid-century labor movement was the age of "the cash payoff, the sweetheart contract, and the gangland beating. It was part of the industrial relations system."

The Organized Crime Committee felt the Detroit police made no serious attempt to solve the crime or curb the anti-union violence. "The Detroit police saw industrial violence as little more significant than a bar brawl," Lichtenstein wrote.

Six years later, Wayne County Prosecutor O'Brien announced at a Detroit press conference that he had solved the Reuther shooting. Arrest warrants were issued for Santo Perrone, Carl B. Renda, Peter M. Lombardo, and Clarence Jacobs.

Donald Ritchie, an ex-con with connections with the Perrones, made a secret arrangement with UAW officials. Ritchie agreed to rat out the people involved with the Reuther shooting for a $25,000 payoff placed in escrow.

If he cooperated with authorities, he would get $5,000 after making the initial statement to the prosecutor and the arrest warrants were issued, an additional $10,000 payable when those named in the warrants were bound over for trial, and another $10,000 when convicted. If murdered before he could cash-in, Ritchie wanted the reward given to his common-law wife.

Part of Ritchie's statement to Prosecutor O'Brien reads, "The night of the shooting, I was picked up at a gas station. The car was a red Mercury.... I sat in the back seat. Clarence Jacobs drove and Peter Lombardo sat in the front seat with Jacobs. The shotgun was in the front seat between (them)--a Winchester 12 gauge pump. I was there in case there was any trouble. If anything happened, I was to drive the car away.

"Jacobs did the shooting. He was the only one who got out of the car.... I heard the report from the gun. Then Jacob got back in the car and said, 'Well, I knocked the bastard down.' After the job, they dropped me off at Helen's bar.... I had some drinks and went to see Carl Renda. He got a bundle of cash and handed it to me. I took a taxi to Windsor and counted my money after I got to Canada. Exactly five grand."

As prearranged, when Ritchie came back across the international border, he was immediately placed under the protection of the Detroit Police Department. While waiting for the trial so he could give his star-witness testimony, he told the Detroit police detail assigned to protect him that he wanted to take a shower. Ritchie escaped from a bathroom window at the Statler Hilton Hotel on Grand Circus Park. Ritchie was on the lam. Once again, he took a cab to safety across the United States/Canada border.

At the same time, Ritchie's common law wife was given the first installment of the escrow account. Ritchie delivered on the first part of the bargain. He made an initial statement and the suspects were charged. The UAW had no choice but pay off the first escrow installment. Ritchie dropped a dime from Canada and denied his entire confession to a Detroit Free Press reporter. He said he needed the money and was taking the UAW for a ride.

Without Ritchie's testimony, Prosecutor O'Brien's case collapsed leaving him with an embarrassing fiasco. He dropped all the charges. The UAW made the stupid mistake of paying a witness. The labor organization had been swindled out of $5,000 by an ex-con.

***

Seconds before the confrontation.The assassination attempt was not the first time Walter Reuther ran afoul of the car companies. On May 26, 1937, Reuther and several other labor organizers were badly beaten by Ford Motor Company Security men in what history notes as the Battle of the Overpass. This was Ford's security chief Harry Bennett's opening salvo against labor organization inside the Ford empire.

Seconds before the confrontation.The assassination attempt was not the first time Walter Reuther ran afoul of the car companies. On May 26, 1937, Reuther and several other labor organizers were badly beaten by Ford Motor Company Security men in what history notes as the Battle of the Overpass. This was Ford's security chief Harry Bennett's opening salvo against labor organization inside the Ford empire. Bob Morris writes, "This was a public relations disaster for Ford, as a Detroit News photographer captured the beating of the labor leaders. The photos... were published around the world. The attack on Walter Reuther made him one of the most recognized labor leaders in Detroit and the country."

Walter Reuther and Richard Frankensteen

Walter Reuther and Richard Frankensteen Arnold Freeman of the Detroit Times reported that Bennett assembled semi-permanent gangs of thugs known as outside squads. A member of one of those squads "Fats Perry" turned state's evidence in 1939. He testified,

"These squads were armed with pistols, whips, blackjacks, lengths of rubber hose called persuaders, and a variety of weapons, some of which made up by a department in the (Rouge) plant itself."

***

On May11, 1970, The New York Times reported Walter Reuther, his wife May, and four other people died in the crash of a two-engined Lear Jet on May 9th at 9:33 PM. The chartered jet--on its final approach to the Pellston Regional Airport, arriving from Detroit in the fog and rain--broke through the clouds short of the runway and clipped some tree tops sheering off both wings. The plane crashed and burst into a fireball a mile southwest of the airport.

The Federal Aviation Administration listed a faulty altimeter as the official cause. No charges were ever filed, but the persistent belief is the crash was not an accident. Reuther was sixty-two.

Silent clip of police investigating Walter Reuther's home after the assassination attempt. His wife speaks briefly to the press. Fingerprints are taken outside the Reuther home.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZMayuqfDpuI

Published on October 18, 2015 08:24

October 9, 2015

Detroit's Femme Fatale Nelle (Lassiter)

Nelle Lassiter faces newsmen-February 24, 1960.On Tuesday, February 23, 1960, Mrs. Nelle Eaker Lassiter--a striking, thirty-eight year old, silver-blonde and shapely former model--was arrested and charged with being the mastermind behind the April 7, 1959 murder of her husband, Parvin (Bill) Lassiter, co-owner of a successful automobile dealership in Royal Oak, Michigan.

Nelle Lassiter faces newsmen-February 24, 1960.On Tuesday, February 23, 1960, Mrs. Nelle Eaker Lassiter--a striking, thirty-eight year old, silver-blonde and shapely former model--was arrested and charged with being the mastermind behind the April 7, 1959 murder of her husband, Parvin (Bill) Lassiter, co-owner of a successful automobile dealership in Royal Oak, Michigan. One newspaper account of the arrest says Nelle was on her way to Detroit's City-County building believing she was to be a prosecution witness at the murder trial of her husband. Another account reports police arrested her at an unnamed hospital where she was visiting her daughter and newborn grandson.

The week before her arrest, The Miami News reported, "Nelle Lassiter sobbed and became hysterical with apparent widow's grief while testifying against the three men on trial for bludgeoning and shooting her husband."

Gordon WatsonSeveral hours after her arrest, Nelle Lassiter's lover--and her husband's business partner--was arrested in Los Angeles on a fugitive warrant. Gordon Watson moved to California with his wife and children shortly after Parvin Lassiter's fatal beating and shooting.

Gordon WatsonSeveral hours after her arrest, Nelle Lassiter's lover--and her husband's business partner--was arrested in Los Angeles on a fugitive warrant. Gordon Watson moved to California with his wife and children shortly after Parvin Lassiter's fatal beating and shooting.The arrests of Nelle Lassiter and Gordon Watson were the result of their defense attorneys asking the prosecution in open court if they had investigated the possibility this was a murder-for-profit case. That left the door open for a second-degree murder plea for their clients Roy C. Hicks (37), Richard Jones (27), and Charles Nash (43) who were being tried on first-degree murder charges. The three men were all former employees of Parvin Lassiter. The charges against Mrs. Lassiter and Watson stemmed from statements made by Jones and Hicks to their attorneys.

Mrs. Lassiter and Watson were named in the warrant as "the principal perpetrators and procurers of this evil crime." Both denied any knowledge of the killing. The Buffalo Courier-Express reported "Mrs. Nelle Lassiter pleaded innocent on charges she had her husband slain in a murder-for-hire plot to grab his fortune and clear the path for her romance with his business partner. She looked tired and drawn after spending the night in county jail instead of her fashionable home" in Beverly Hills, Michigan.

Parvin "Bill" LassiterThe body of Parvin Lassiter was found on a private estate near Willow Run Airport. Investigators discovered Parvin had returned from a trip to Arizona when he was lured into a waiting car, beaten behind the head, shot in the eye, and thrown in a ditch.

Parvin "Bill" LassiterThe body of Parvin Lassiter was found on a private estate near Willow Run Airport. Investigators discovered Parvin had returned from a trip to Arizona when he was lured into a waiting car, beaten behind the head, shot in the eye, and thrown in a ditch.At Nelle's pretrial hearing in a Dearborn Township courtroom, Richard Jones took the stand. He testified, "Gordon Watson took a one-inch stack of bills from Mrs. Lassiter in the summer of 1958 which Watson called the down payment for the assassination of Parvin Lassiter."

The transaction took place in the office of the Royal Oak dealership where Watson and Parvin Lassiter were co-owners. Jones added, "Mrs. Lassiter told Watson 'It won't be long now, Darling, before we can be together forever'."

The Kentucky New Era reported "Nelle Lassiter wailed loudly 'That's not true, that's not true!' The high-strung blonde broke into sobs and clutched the arm of her defense attorney--Joseph Louisell.

"The judge was unable to restore order and called for a recess. After Mrs. Lassiter regained her composure, the hearing resumed twenty minutes later. Forty-five year-old Watson sat calmly in the courtroom throughout the disturbance."

Roy C. Hicks testified the three men were promised $50,000 worth of automobiles to procure the slaying. When Hicks' girlfriend Barbara McCommon testified, she told the court that Nelle Lassiter said Parvin was mean to her and treated her badly. She did not love him anymore. Under prosecution immunity, Miss McCommon suggested Mrs. Lassiter get rid of her husband and contact her boyfriend--Roy Hicks.

Mrs. Lassiter shouted out, "That's a lie! Why are they saying these things? I didn't kill my husband." She whipped herself into a frenzy and had a nervous breakdown in court. This was the fifth time the pre-trial hearing had been interrupted. Defense attorney Joseph Louisell requested Judge Joseph G. Rashid order Mrs. Lassiter to be examined by qualified mental health professionals to judge her competency to stand trial.

The Detroit Free Press reported Nelle Lassiter's sanity hearing took place at her bedside in Jenning's Memorial Hospital. "Mrs. Lassiter, wearing a standard white hospital gown, lay motionless on a narrow bed. Two of three psychiatrists who examined Lassiter found her to be insane within the scope of the law and were prepared to testify to that in open court.

Judge Rashid ruled, "I have no choice but to declare a mistrial and turn Mrs. Lassiter over to the sheriff for removal to Ionia State Hospital until she is restored."

The murder trial of her co-conspirator and co-defendant Gordon Watson continued without "the trim, blonde grandmother." He got a life sentence. Joseph Louisell was eventually able to get Nelle Lassiter acquitted. Afterwards, she vanished from the scrutiny of the public eye.

Published on October 09, 2015 14:22

October 1, 2015

A Crime to Remember--John Norman Collins Episode--"A New Kind of Monster"

In early 2013, I was asked to participate on a new Investigation Discovery Channel series named A Crime to Remember. One of the producer's staffers had read a number of my Fornology blog posts on John Norman Collins and the Washtenaw County murders of 1967-1969. At Discovery Channel's expense, I was flown to New York for my first television appearance. What a thrill!

Also included in the program to provide commentary were former Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas Harvey, forensic psychologist and author Dr. Katherine Ramsland, former Eastern Michigan University campus patrolman Larry Mathewson, and reporter Marti Link. The episode is entitled, "A New Kind of Monster."

Also included in the program to provide commentary were former Washtenaw County Sheriff Douglas Harvey, forensic psychologist and author Dr. Katherine Ramsland, former Eastern Michigan University campus patrolman Larry Mathewson, and reporter Marti Link. The episode is entitled, "A New Kind of Monster."After almost five years of research and interviewing people connected with these cases, my treatment of this subject matter has the benefit of close to fifty years of hindsight and should be completed early next year. In addition to the seven murders and the restored court proceedings (trial records were purged by Washtenaw County officials) my book will include for the first time ever, John Norman Collins' prison years and his attempts to circumvent his life sentence without parole.

"A New Kind of Monster" was the second most popular episode of the Emmy winning first season of the series. It can be accessed at the link below, or it can be seen On Demand and at YouTube, Amazon Prime, IMDb, and Netflix.

http://www.investigationdiscovery.com/tv-shows/a-crime-to-remember/a-crime-to-remember-videos/1967-the-co-ed-killer-facts/

Published on October 01, 2015 08:41

September 9, 2015

Ypsilanti History--The Town and the Gown

Three forward-looking American businessmen with thick billfolds bought up the French land claims along both sides of the Huron River in 1825. They surveyed the cleared farmland for a new town they named Ypsilanti. Although odd and difficult to pronounce for people unfamiliar with the name, Ypsilanti it is unique and has served the city well. The proper pronunciation is /ip'si-lan-tee/ but never /yip'sil-lan-tee/. Visitors might want to refrain from using the term Ypsitucky. Many residents consider the term offensive.

Three forward-looking American businessmen with thick billfolds bought up the French land claims along both sides of the Huron River in 1825. They surveyed the cleared farmland for a new town they named Ypsilanti. Although odd and difficult to pronounce for people unfamiliar with the name, Ypsilanti it is unique and has served the city well. The proper pronunciation is /ip'si-lan-tee/ but never /yip'sil-lan-tee/. Visitors might want to refrain from using the term Ypsitucky. Many residents consider the term offensive.The City of Ypsilanti came of age with the founding of Michigan State Normal School in 1849. Classes began on March 29, 1853, with the completion of their newly constructed, three-story classroom building. The school building was destroyed by fire in October 1859 but was rebuilt and ready for classes six months later.

Michigan's system of education was patterned after the German system. The mission of normal schools was the "normalization" of teaching standards and practices. Normal schools trained teachers for the common schools which were popping up around the state. In 1899, Michigan State Normal School was the second normal school in the nation to adopt a four-year curriculum and earn the distinction of college.

When World War Two ended, the passage of the Servicemen's Readjustment Act (the G.I. Bill) helped Michigan State Normal College expand with new buildings and new departments offering a broader range of offerings to accommodate the increased enrollment of veterans.

The Normal College became Eastern Michigan College in 1956, but that was short-lived. When Eastern Michigan established its graduate school in 1959, it was upgraded to university status.

The Normal College became Eastern Michigan College in 1956, but that was short-lived. When Eastern Michigan established its graduate school in 1959, it was upgraded to university status.Today, Eastern Michigan University offers degrees and programs at the bachelor, master, specialist, and doctoral levels. Since 1991, Eastern Michigan is the largest producer of educational personnel in the country. We are everywhere.

The City of Ypsilanti and Eastern Michigan University's Board of Regents have a one hundred and sixty-five year shared history. They have survived catastrophic fires, angry storms, and devastating winds together. They have been witness to every American war since the Civil War, weathered the Great Depression, and grieved over the political assassinations of the 1960s.

A two year reign of terror stalked Ypsilanti from July 1967 through July 1969. Seven young women--three of them EMU coeds and one an Ypsilanti teen--were wantonly murdered by a serial killer. This sustained nightmare left an indelible impression on residents during those dark days. Both institutions were bound by fear and helplessness.

A lot of water--and history--has flowed past the Peninsula Paper Company dam on the Huron River. Political insiders and local historians say there have been a number of Town and Gown spats over the years, but overall, the relationship between the city and the university has been beneficial. EMU is currently Ypsilanti's largest employer.

Looking down West Street Cross StreetUnlike the University of Michigan campus which is inseparable from the City of Ann Arbor, Eastern Michigan's campus is set apart from Ypsilanti's downtown--with one notable exception--EMU's College of Business located on Michigan Avenue. The university and the city need to find more ways to work together to promote each others mutual interests.

Looking down West Street Cross StreetUnlike the University of Michigan campus which is inseparable from the City of Ann Arbor, Eastern Michigan's campus is set apart from Ypsilanti's downtown--with one notable exception--EMU's College of Business located on Michigan Avenue. The university and the city need to find more ways to work together to promote each others mutual interests.Ypsilanti has untapped potential to once again be a place to go, rather than a place to avoid or drive past on the Interstate. Ypsilanti needs some can-do people with vision. If a mass transit scheme can be worked out--like a commuter rail stop in Depot Town--the city's economic development department needs to be ready to capitalize on every opportunity.

Published on September 09, 2015 16:25

September 1, 2015

Ypsilanti History--The Boom and the Bust Years

In 1851, frontier downtown Ypsilanti burned down and was rebuilt with red common brick. By the late 1880s, many Michigan rural communities began erecting ornate water towers responding to their increasing populations and industrialization after the Civil War. Sanitation and drinking water improved, while increased water pressure made fire-fighting more responsive and successful.

In 1851, frontier downtown Ypsilanti burned down and was rebuilt with red common brick. By the late 1880s, many Michigan rural communities began erecting ornate water towers responding to their increasing populations and industrialization after the Civil War. Sanitation and drinking water improved, while increased water pressure made fire-fighting more responsive and successful.  Ypsilanti Water Tower - 1889These nineteenth century water towers were landmarks and symbols of civic pride, but none was as iconic as the Ypsilanti Water Tower, built across from Eastern Michigan University on Ypsilanti's highest point. This pubic-funded water supply system took only ten months to build and was finished in February 1890. It consisted of seventeen miles of feeder pipe, one hundred and thirty-two fire hydrants, a pumping station, and a one hundred and forty-eight foot tall tower. The octagonal cupola on top was removed in 1906 because of fears strong winds might undermine it and send it toppling below.

Ypsilanti Water Tower - 1889These nineteenth century water towers were landmarks and symbols of civic pride, but none was as iconic as the Ypsilanti Water Tower, built across from Eastern Michigan University on Ypsilanti's highest point. This pubic-funded water supply system took only ten months to build and was finished in February 1890. It consisted of seventeen miles of feeder pipe, one hundred and thirty-two fire hydrants, a pumping station, and a one hundred and forty-eight foot tall tower. The octagonal cupola on top was removed in 1906 because of fears strong winds might undermine it and send it toppling below.At the turn of the twentieth century, Ypsilanti was a thriving farming community surrounded by thousands of acres of fertile land under the plow. The area was also known for its orchards and wooded tracts teeming with wildlife. The city boasted having some of the best representations of Victorian architecture in Southeastern Michigan. The town prospered.

Daniel Quirk mansion today.

Daniel Quirk mansion today.World War I transformed America overnight from a rural farming country into an urban one. When the weight of the Great Depression hit the heartland, many of the family farms in Ypsilanti fell into disrepair or were simply abandoned. In fundamental ways, Ypsilanti was a microcosm of the American economy. Its fortunes waxed and waned with those of the country. Things were tough all over.

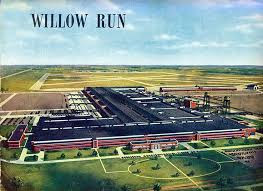

With another World War looming, automobile magnate Henry Ford and his son Edsel did their part for the war effort by quickly building the world’s largest and most modern airplane factory. The Willow Run B-24 Liberator Bomber Plant was built on orchard land owned by the Ford family, just east of Ypsilanti.

With another World War looming, automobile magnate Henry Ford and his son Edsel did their part for the war effort by quickly building the world’s largest and most modern airplane factory. The Willow Run B-24 Liberator Bomber Plant was built on orchard land owned by the Ford family, just east of Ypsilanti.After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, the United States experienced a wave of patriotism, and Ypsilanti was no different. There was yet another drain of manpower for the war effort—the second time in twenty-seven years. Another generation of Ypsilanti’s finest answered the call to serve their country.

At peak production, the Willow Run plant could produce one plane every hour.

At peak production, the Willow Run plant could produce one plane every hour.But that left Henry Ford desperate for workers to run the Willow Run B-24 bomber plant, so the company recruited heavily from Kentucky and West Virginia to help make up the manpower shortage. In the most dramatic demographic shift in the area since the white man drove the red man west, Ypsilanti went from a rural sunrise-to-sundown farming community to a round-the-clock factory town.

Ypsilanti became a boom town. Suddenly, downtown was beset with unattached men who had money in their pockets looking for a good time—some were single and some were not. Michigan Avenue bars did a box office business attracting thirsty and bored customers from the plant.

Because the bomber plant ran three shifts, the bars had customers all day long. Drunken brawls were not uncommon among rowdy plant workers, but problems also broke out between the workers and townspeople--often over women.

This tense atmosphere gave downtown Ypsilanti an edge changing its character.

Residents bemoaned the changes to their town and called the newcomers Ypsituckians. The east side of town quickly became the blue collar residential area, as it was nearest to the bomber plant.

Because of the immediate need to house these men, some residents rented out bedrooms in shifts. Many of the beautiful old period homes were subdivided into small apartments or became boarding houses. In Willow Run, barracks-style housing was hastily thrown up to address the desperate situation. Some people worked double shifts and lived out of their cars until they could get situated.

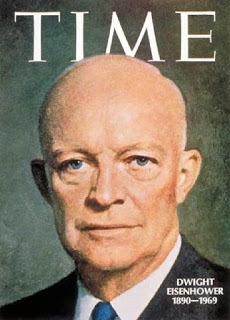

Thirty-fourth President of the United StatesAlmost as quickly as they began, the boom days ended when the war did. Ypsilanti went into a postwar, economic slump. In 1956, the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration established the Federal Interstate Highway System. I-94 was built a mile south of downtown Ypsilanti. This changed traffic patterns and hurt the main street business community. By the 1970s, downtown Ypsilanti and Depot Town showed signs of neglect.

Thirty-fourth President of the United StatesAlmost as quickly as they began, the boom days ended when the war did. Ypsilanti went into a postwar, economic slump. In 1956, the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration established the Federal Interstate Highway System. I-94 was built a mile south of downtown Ypsilanti. This changed traffic patterns and hurt the main street business community. By the 1970s, downtown Ypsilanti and Depot Town showed signs of neglect.More details about Ypsi's Water Tower:

Published on September 01, 2015 06:46