Gregory A. Fournier's Blog, page 26

January 22, 2017

History of The Lone Ranger On Television (2/3)

The radio success of The Lone Ranger program was phenomenal. It ran from January 30, 1933, through September 3, 1954, for a total of 2,956 episodes.

The radio success of The Lone Ranger program was phenomenal. It ran from January 30, 1933, through September 3, 1954, for a total of 2,956 episodes. The Lone Ranger brand name was a merchandising bonanza. Soon, novels, comic books, jigsaw puzzles, authentic hats, masks, Western style shirts, and replica twin gun and dual holster sets with silver bullets were available in every toy store in America.

George W. Trendle, founder and general manager of WXYZ Radio in Detroit wanted to bring The Lone Ranger to the new medium of television in 1948.

Brace Beemer had played the title role on radio for eight years and wanted the television part. Trendle felt that Beemer was too long in the tooth and sat too low in the saddle at forty-six-years-old for the role. Brace didn't have the square jaw and rugged good looks that the role required.

George W. Trendle watched numerous Western and adventure movies and liked Clayton Moore's versatility as an actor. Moore had extensive film, movie serial, and television experience.

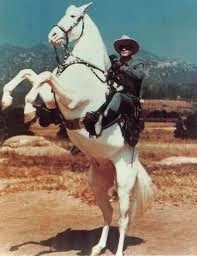

The white hat and the black mask looked good on Moore. The Lone Ranger jumped off the small television screen and into America's living rooms on September 15, 1949. In all, there were two-hundred and twenty-one episodes made.

John HartThe third year of the series found Clayton Moore sitting out the season because of a contract dispute. Another actor, John Hart, donned the uniform. The mask made the transition to a different actor easier for the audience to accept, but Hart didn't move the same way, nor did his voice match. And something was different about the chemistry between the masked man and Tonto.

John HartThe third year of the series found Clayton Moore sitting out the season because of a contract dispute. Another actor, John Hart, donned the uniform. The mask made the transition to a different actor easier for the audience to accept, but Hart didn't move the same way, nor did his voice match. And something was different about the chemistry between the masked man and Tonto. The first few episodes with the new Lone Ranger were shot in documentary style with a narrator to ease the transition to the new voice. Hart was generally accepted in the role, but fan favorite, Clayton Moore was back in the saddle for the fourth and fifth season, the only one shot in color.

In addition to a fatter contract, Moore wanted meatier roles to stretch himself as an actor. He liked playing the classic, two-dimensional good guy, but it wasn't enough. To take advantage of his acting ability, Moore began playing dual roles as the Lone Ranger going undercover. Sometimes he was an old prospector or a vagrant of some kind. The character became a master of disguise and infiltrated gangs and outsmarted the bad guys.

No more episodes were made for television after 1955, but the show was so popular with the audience that it managed to hold on to its time slot through the 1957 season.

Through it all, Jay Silverheels, a Mohawk Indian actor, played the role of Tonto, the masked man's trusted companion. The Lone Ranger always used perfect grammar, which may have pleased parents and English teachers, but it didn't seem to make much of an impression on Tonto. The Lone Ranger was his "kemo sabe," his trusty scout.

In later years, Jay Silverheels made an appearance on The Tonight Show, with Johnny Carson, and was asked about Tonto's clipped dialogue. He said it bothered him, but that's what the script required, so he read the lines.

When his role as Tonto ran its course, Silverheels played minor supporting roles in the movies and on television into the early 1970s. He enjoyed harness racing in his later years and actively spoke out about the "Uncle Tomahawk" roles Indian actors were forced to play.

Clayton Moore continued to make appearances as the Lone Ranger for the rest of his public life. In 1979, he was banned from wearing the mask at appearances because of a new Lone Ranger movie that was to come out in 1981. The producers took out a court order against the aging but beloved actor. It was a public relations disaster for the film which tanked at the box office.

Clayton Moore continued to make appearances as the Lone Ranger for the rest of his public life. In 1979, he was banned from wearing the mask at appearances because of a new Lone Ranger movie that was to come out in 1981. The producers took out a court order against the aging but beloved actor. It was a public relations disaster for the film which tanked at the box office.Clayton Moore got so much free publicity that he started making appearances in some specially designed Foster-Grant sunglasses and landed a fat endorsement contract. "Who is that man behind those Foster Grants?" began the successful ad campaign which played on the signature ending of each television episode, "Who was that masked man?".

His commercials aired repeatedly which delighted fans, proving that you can't keep a good man down. In 1984, the court order was lifted and Moore could once again wear the mask while making appearances. By the 1990s, Clayton Moore retired from public life.

Jay Thomas tells a funny story about Clayton Moore on the David Letterman Show: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KFabfnfhIaY

Published on January 22, 2017 07:29

January 16, 2017

History of The Lone Ranger--The Radio Years (1/3)

The Lone Ranger! "Hi Yo Silver!"

The Lone Ranger! "Hi Yo Silver!" "A fiery horse with the speed of light, a cloud of dust and a hearty 'Hi Yo Silver!' The Lone Ranger--with his faithful Indian companion Tonto--the daring and resourceful masked rider of the plains led the fight for law and order in the early west. Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear. The Lone Ranger rides again!" Baby Boomers everywhere will remember those rousing words recited over Rossini's classical music The William Tell Overture. The television version of the masked man hit the small screen in a big way, but the character was already well-established on a radio show first broadcast from Detroit three times a week on WXYZ radio in 1933. Fran Striker was the creator of the character; George W. Trendle was the producer of the show; and Earl Graser was the first Lone Ranger on the radio.

Earle GraserGraser had a deep, authoritive, vibrant voice that sounded much older than his thirty-two years. On his way home from rehearsals at the station on April 8, 1941, he fell asleep at the wheel and veered into a parked trailer silencing one of America's most popular radio voices. He had been on the air as the Lone Ranger for eight years. The show was scheduled to air the next night, but who would take over the role? Trendle had to find someone fast. Mike Wallace might work. He would become a journalist on Sixty Minutes decades later, but he was presently the narrator on the popular The Green Hornet program at WXYZ. Mike Wallace was available, but he had questionable dramatic voice acting ability.

Earle GraserGraser had a deep, authoritive, vibrant voice that sounded much older than his thirty-two years. On his way home from rehearsals at the station on April 8, 1941, he fell asleep at the wheel and veered into a parked trailer silencing one of America's most popular radio voices. He had been on the air as the Lone Ranger for eight years. The show was scheduled to air the next night, but who would take over the role? Trendle had to find someone fast. Mike Wallace might work. He would become a journalist on Sixty Minutes decades later, but he was presently the narrator on the popular The Green Hornet program at WXYZ. Mike Wallace was available, but he had questionable dramatic voice acting ability.

Brace BeemerIt was decided that Brace Beemer, who narrated The Lone Ranger, was their best choice on short notice. He had already been doing publicity photos for The Lone Ranger, and now he could make public appearances around the Detroit area as well. Best of all, Beemer's voice was similar to Graser's with a slight headcold. Good enough! To ease the transition for listeners, the masked man would be wounded for the next few episodes and speak with a weak, raspy voice. Brace Beemer was an excellent front man for the program. He was six feet tall, handsome, and an excellent horseman. He had no problem booming out "Hi-Yo, Silver"during the program, but he couldn't handle the ending when he had to say "Hi-Yo, Silver, away." It didn't sound right to Trendle or the sound engineers, so they inserted a recording of Graser saying the line at the end of the program. In a 1944 radio poll, The Lone Ranger placed number one in popularity. In all, there were 2,956 radio episodes made. The Lone Ranger television show opening with theme song "The William Tell Overture." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p9lf76xOA5k

Brace BeemerIt was decided that Brace Beemer, who narrated The Lone Ranger, was their best choice on short notice. He had already been doing publicity photos for The Lone Ranger, and now he could make public appearances around the Detroit area as well. Best of all, Beemer's voice was similar to Graser's with a slight headcold. Good enough! To ease the transition for listeners, the masked man would be wounded for the next few episodes and speak with a weak, raspy voice. Brace Beemer was an excellent front man for the program. He was six feet tall, handsome, and an excellent horseman. He had no problem booming out "Hi-Yo, Silver"during the program, but he couldn't handle the ending when he had to say "Hi-Yo, Silver, away." It didn't sound right to Trendle or the sound engineers, so they inserted a recording of Graser saying the line at the end of the program. In a 1944 radio poll, The Lone Ranger placed number one in popularity. In all, there were 2,956 radio episodes made. The Lone Ranger television show opening with theme song "The William Tell Overture." https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p9lf76xOA5k

Published on January 16, 2017 07:46

January 11, 2017

The EDSEL--Car of the Future--Really?

I grew up in the Dearborn, Michigan area--the center of what is commonly known as Ford Country. Most people in the area buy Ford products--unless of course they work for Chrysler or General Motors. Brand loyalty is encouraged by the automotive companies and most workers comply--especially when the company offers employee discounts.

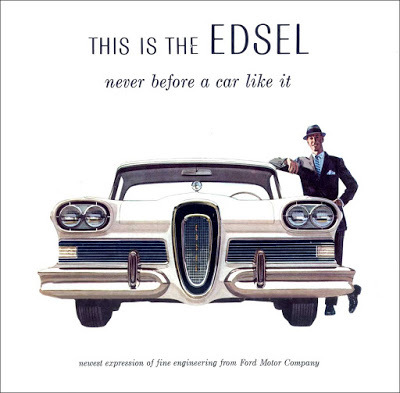

When Ford Motor Company came out with the Edsel in the 1958 model year, the company upgraded its Lincoln Division to compete with General Motor's luxury Cadillac. Ford needed a premium vehicle to fill the intermediate slot vacated by Lincoln to compete with Oldsmobile, Buick, and DeSoto. Ford promoted the Edsel as the product of extensive research and development. Their sophisticated market analysis indicated to the suits at Ford's that they had a winner.

The Edsel was touted as the car of the future. Ford executives were confident of brand acceptance by the car buying public. Innovative features like a rolling-dome speedometer, engine warning lights, an available Teletouch pushbutton shifting system, self-adjusting brakes, optional seat belts, and child-proof rear door locks would surely capture the imagination of modern-thinking consumers.

The Edsel was touted as the car of the future. Ford executives were confident of brand acceptance by the car buying public. Innovative features like a rolling-dome speedometer, engine warning lights, an available Teletouch pushbutton shifting system, self-adjusting brakes, optional seat belts, and child-proof rear door locks would surely capture the imagination of modern-thinking consumers.The day after the Edsel was introduced, The New York Times dubbed it the "reborn LaSalle"--a nameplate that disappeared in the early 1940s. So much for the car of the future concept. Once the Edsel hit the streets, the public thought it was unattractive, overpriced, and overhyped. The car's production was stopped after three years of under performing in Ford and Mercury showrooms.

Ford Motor Company lost $250 million on the project. Edsel's failure was across the board. Popular culture thought the car's styling was odd. The nameplate's trademark horsecollar grille was said to resemble "an Oldsmobile sucking a lemon." The Teletouch pushbutton transmission was problematic being centered on the steering wheel hub where most cars had their warning horn. Some drivers accidently shifted when they meant to sound their horn. Another unforeseen problem was that the pushbutton transmission was not suited for street racing, so the Edsel became known as an old man's car.

What turned off other consumers was the car's sticker price which placed it in direct competition with Mercury--Ford's sister division. Further complicating matters, the low priced Volkswagen Beetle hit the American car market in 1957. Many younger buyers were fascinated by the odd-looking vehicle with the incredible gas mileage. The Edsel was a gas guzzler.

Consumer Reports blamed the car's poor workmanship. For instance, the trunk leaked in heavy rain, and the pushbutton transmission was fraught with technical problems. Marketing experts insisted the Edsel was doomed from the start because of Ford's inability to understand the American consumer and market trends. Automotive historians believe the Edsel was the wrong car at the wrong time.

Edsel FordUnfairly, the name Edsel became synonymous with epic failure. Named after Henry Ford's only son, this car became a posthumous slap in the face to the man who mobilized his family's vast industrial resources to produce B-24 Liberator bombers, instrumental in helping win World War II. Edsel Ford's legacy deserved better.

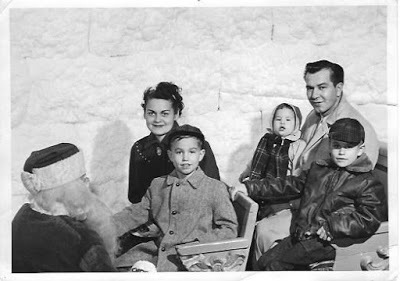

Edsel FordUnfairly, the name Edsel became synonymous with epic failure. Named after Henry Ford's only son, this car became a posthumous slap in the face to the man who mobilized his family's vast industrial resources to produce B-24 Liberator bombers, instrumental in helping win World War II. Edsel Ford's legacy deserved better.As luck would have it, my father bought a brand-new Edsel in 1959. It was Christmas time and I was eleven years old. After my brothers and I had our photograph taken with Santa at Muirhead's Department Store, my dad brought us to the Ford Dealership across the street for our family Christmas present.

He went into an office and signed a few papers, then the salesman handed over the keys. As we were driving away from the dealership, I remember snowflake clusters illuminated by the car's headlights. It was magical. By the time my family got home, we were intoxicated with the new-car smell of fresh upholstery and uncured lacquer.

He went into an office and signed a few papers, then the salesman handed over the keys. As we were driving away from the dealership, I remember snowflake clusters illuminated by the car's headlights. It was magical. By the time my family got home, we were intoxicated with the new-car smell of fresh upholstery and uncured lacquer.Later that week, my dad was celebrating with his friends and had a few too many before coming home from work. On the way, he hit an ice patch and lost control of the car, wrapping it around a telephone pole. He was relatively uninjured, but the Edsel was totaled. I remember we had that Edsel for such a short time I can't remember what color it was.

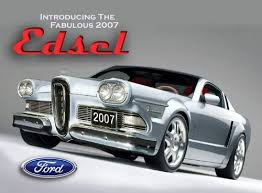

Edsel concept car.Misfortune aside, I've always had a love for the Edsel and often wished Ford would find a market for the nameplate and start production again. That may never happen, but a boy can dream.

Edsel concept car.Misfortune aside, I've always had a love for the Edsel and often wished Ford would find a market for the nameplate and start production again. That may never happen, but a boy can dream.Here is a Psychology Today article on how the Edsel got its name:

Published on January 11, 2017 07:36

January 6, 2017

Allen Park, Michigan, F4 Tornado--May 12th 1956

Michigan tornadoes since 1950 when records began being kept.

Michigan tornadoes since 1950 when records began being kept.A tornado is a violent rotating column of air descending from a thunderstorm and touching down on the ground, usually spinning counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere. There is no shortage of tornadoes in the deadly swatch of America called "tornado alley"--a nickname given to a large area beginning in Texas and running through the Great Plains states northeast through the Midwest and the Great Lakes, stretching into Canada. The official boundaries are not clearly defined.

The term was first used in 1952 as the title of a research project by U.S. Air Force meteorologists Major Ernest J. Fawbush and Captain Robert C. Miller. Tornado season runs from mid-March into September--the worst month being June.

Allen Park, Michigan, is located south of Detroit in an area known as Downriver--statistically a low risk area for tornadoes. But on May 12th, 1956, the day before Mothers' Day, an F4 tornado ripped through town and injured twenty-two people, damaging property in its wake.

An F4 rating is listed as "devastating" [207 mph to 260 mph] by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA]. Tornado ranking was developed by T. Theodore Fujita and first used in 1973 and enhanced in 2007 [see link for more detailed information].

--from Images of America [series] Allen Park by Sharon Broglin

--from Images of America [series] Allen Park by Sharon BroglinAllen Park residents remember the 1956 tornado as one of the worst weather events in their history, the twister touching down on Ecorse Road and cutting across town. Eyewitnesses remember that it traveled down the railroad tracks near homes close to Jaycee Park. There was damage to the Westwood Dairy Bar at Allen Road and Roosevelt Street. Also on Allen Road, Gee's Drive-in hamburger joint had the roof torn off which landed in a yard several blocks away. Across Allen Road, the tornado took out all the front windows of North Junior High School, and close by, all the trees in Thomas Park were leveled.

This was a lucky day for Allen Parkers, only twenty-two people were injured with no fatalities. Flint, Michigan, had a tornado the same day with three fatalities and one-hundred, sixteen injuries. Only three years before, the Flint area had an F5 tornado, the most devastating tornado in Michigan state history--with one-hundred, sixteen deaths and eight-hundred, forty-four injuries.

NOAA Severe Weather 101--Tornado Basics: http://www.nssl.noaa.gov/education/svrwx101/tornadoes/

More information on the Fujita tornado rating scale: http://www.angelfire.com/nj4/tornadoes/page3.html

Published on January 06, 2017 06:45

January 1, 2017

The American Clown's Fall From Grace

The modern circus clown character was created in the 19th century. These performers used broad physical comedy, often in mime (without voice). Circus clowns were known for their distinctive makeup, outlandish wigs, colorful oversized costumes, and exaggerated footwear. They provided diversion for circus crowds while roustabouts set up for the next act which might involve animals or featured performers. Clowns would weave in and out of the spotlight to create an atmosphere of safe fun for their audience.

The modern circus clown character was created in the 19th century. These performers used broad physical comedy, often in mime (without voice). Circus clowns were known for their distinctive makeup, outlandish wigs, colorful oversized costumes, and exaggerated footwear. They provided diversion for circus crowds while roustabouts set up for the next act which might involve animals or featured performers. Clowns would weave in and out of the spotlight to create an atmosphere of safe fun for their audience.Circus clowns perform strictly for laughs and to entertain their audience--heavily loaded with children. Their ridiculous antics deal with the absurdities of everyday life and speak to the human condition. Traditionally, clowns are archetypal figures that appear in many of the world's cultures performing a vital social function--a comical diversion from the stress and strain of everyday life.

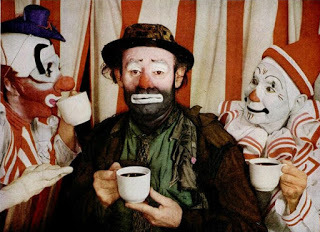

Emmett KellyThe village idiot character lost popularity in America in the early 20th century. The North American circus began to develop new comic characters like the hobo and the tramp. Charlie Chaplin made a career out of the tramp character in the silent film industry. Emmett Kelly's clown character Weary Willie was developed in the 1930s based on Depression era hobos. In early television, Red Skelton portrayed Freddy the Freeloader, a smart-mouthed bum with a heart of gold who could find humor and humanity in any situation.

Emmett KellyThe village idiot character lost popularity in America in the early 20th century. The North American circus began to develop new comic characters like the hobo and the tramp. Charlie Chaplin made a career out of the tramp character in the silent film industry. Emmett Kelly's clown character Weary Willie was developed in the 1930s based on Depression era hobos. In early television, Red Skelton portrayed Freddy the Freeloader, a smart-mouthed bum with a heart of gold who could find humor and humanity in any situation.

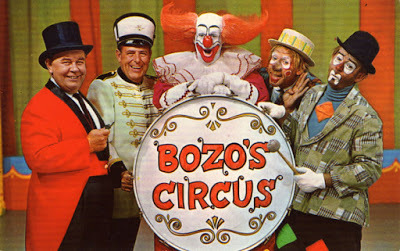

Most Baby Boomers remember Clarabell from the Howdy Doody Show and Bozo the Clown who premiered in 1960 with his own cartoon show. The Bozo character was franchised and Bozos starting appearing in large media markets across America. These signature clowns hosted local shows with a live studio audience of screaming kids interspersed between cartoons.

In 1963, weatherman Willard Scott portrayed the first Ronald McDonald, which quickly became the company's trademark mascot. Because of changing times and different sensibilities, McDonald's recently retired Ronald after 45 years of faithful service.

Pogo/John Wayne GacyThe trend of birthday clowns began in the 1960s and was popular throughout the 1970s. By the end of the 1978, a registered clown in the Chicago area entertained at kid parties and community events under the name of Pogo the Clown. When he was arrested at his home, John Wayne Gacy had sexually assaulted and killed 35 young men. Coast-to-coast newspaper accounts called Gacy the "Killer Clown." What scared parents most... Gacy was given easy access to children under the guise of an innocuous clown. This fueled American's growing fears of "stranger danger" and clowns became the objects of real suspicion.

Pogo/John Wayne GacyThe trend of birthday clowns began in the 1960s and was popular throughout the 1970s. By the end of the 1978, a registered clown in the Chicago area entertained at kid parties and community events under the name of Pogo the Clown. When he was arrested at his home, John Wayne Gacy had sexually assaulted and killed 35 young men. Coast-to-coast newspaper accounts called Gacy the "Killer Clown." What scared parents most... Gacy was given easy access to children under the guise of an innocuous clown. This fueled American's growing fears of "stranger danger" and clowns became the objects of real suspicion.Professor Andrew McConnell Stott of the University of Buffalo believes Charles Dickens invented the scary clown in The Pickwick Papers (1836). Dickens describes an off-duty clown who is a alcoholic that destroys himself to make audiences laugh. Dickens made it difficult for his readers to look at clowns without wondering what was going on beneath the makeup.

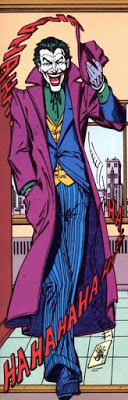

In Batman comics #1 in 1940, supervillain "The Joker" debuted as a psychopathic clown with a warped sense of humor and was the archenemy of "The Caped Crusader." The 1980s gave rise to the "evil clown" character popularized by Stephen King's novel It (1986).

In Batman comics #1 in 1940, supervillain "The Joker" debuted as a psychopathic clown with a warped sense of humor and was the archenemy of "The Caped Crusader." The 1980s gave rise to the "evil clown" character popularized by Stephen King's novel It (1986).Television clowns like "Homey the Clown" on In Living Color and "Crusty the Clown" on The Simpsons forever changed the way Americans view clowns. In recent years, psychologists have coined the term coulorphobia for the fear of clowns. Movies like Killer Klowns from Outer Space (1988), Clownhouse (1989), and the Saw movie franchise (2004) only aggravate the condition.

The great clown scare of 2016 started in August in Green Bay, Wisconsin. With the help of social media and YouTube, Crazy Clowns and Killer Klowns started pranking kids across America causing hysteria among parents and their children. Many schools banned clown costumes at Halloween functions this year.

The great clown scare of 2016 started in August in Green Bay, Wisconsin. With the help of social media and YouTube, Crazy Clowns and Killer Klowns started pranking kids across America causing hysteria among parents and their children. Many schools banned clown costumes at Halloween functions this year.Whether clowning as a profession can survive this recent trend of bad publicity lies with the prevailing public perception. These are complicated times we live in, and Americans are more fearful and cautious of strangers in any guise. Clowns have fallen on hard times.

"What Do the Scary Clowns Want?" New York Times article: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/16/opinion/sunday/what-do-the-scary-clowns-want.html?_r=0

Published on January 01, 2017 06:45

December 26, 2016

Detroit Tobacco Industry Once Known as the Tampa of the North

The following is a guest post researched and written by Mark Lawrence Gade, a Michigan State University graduate and Detroit history enthusiast and docent.

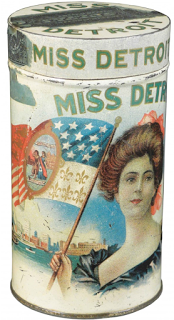

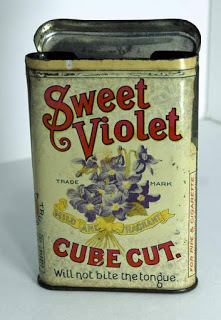

Only four years after becoming a state, the tobacco industry in Michigan got its start when George Miller became the first tobacconist in the city of Detroit in 1841. By the 1850s--with the help of New York's Erie Canal--many Germans migrated to Detroit. These Germans enjoyed smoking and knew how to produce excellent cigars; soon they dominated the city's industry.

Raw material was nearby in Southwestern Ontario. The Canadians produced a high-quality tobacco crop in sandy and silt-loam soil. With tobacco so close at hand, demand for Detroit's quality wrapped cigars turned a cottage industry into an early form of mass production employing thousands of workers throughout the Detroit area.

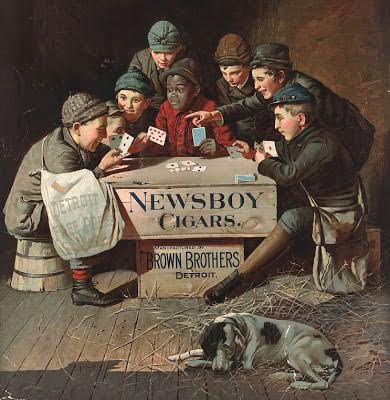

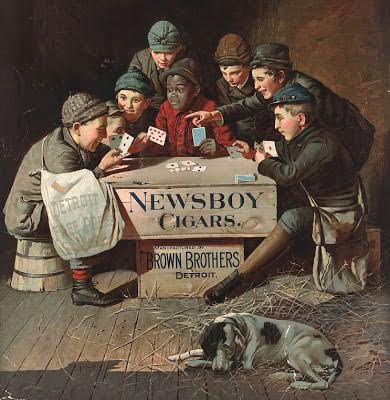

Long before Henry Ford's assembly-line, the cigar industry deconstructed the rolling of cigars into specialized tasks. Each worker performed one part of the process, so few people had the skill to make a whole cigar. Baskets or crates of cigars were moved from station to station down long tables. The process was efficient and Detroit cigars became known for their consistent quality.

Long before Henry Ford's assembly-line, the cigar industry deconstructed the rolling of cigars into specialized tasks. Each worker performed one part of the process, so few people had the skill to make a whole cigar. Baskets or crates of cigars were moved from station to station down long tables. The process was efficient and Detroit cigars became known for their consistent quality.

Then came the American Civil War and the soldier's high demand for tobacco products. To the Yankee or Rebel soldier, tobacco represented the convenience and consolation of home. The hand-rolled cigarette was still an item of luxury, but the cigar represented victory, and the pipe comfort and solace. Soldiers North and South often relaxed by chomping on rich, gooey plugs of chewing tobacco or by smoking delicate clay pipes before, during, and after battles. Much of this tobacco was processed and packaged in Detroit.

Sixteenth governor of the State of Michigan (1873-1877) John Judson Bagley moved to Detroit in 1847. In his early twenties, he started his working career as a humble apprentice in a small chewing tobacco shop. After seven years, he bought the business and renamed it Mayflower Tobacco Company turning his company into an industry leader. Bagley manufactured a rectangular form of chewing tobacco in a tin with a friction-fitted lid that became an industry standard. Bagley made a fortune and helped make Detroit a leader in the manufacture of tobacco products.

Sixteenth governor of the State of Michigan (1873-1877) John Judson Bagley moved to Detroit in 1847. In his early twenties, he started his working career as a humble apprentice in a small chewing tobacco shop. After seven years, he bought the business and renamed it Mayflower Tobacco Company turning his company into an industry leader. Bagley manufactured a rectangular form of chewing tobacco in a tin with a friction-fitted lid that became an industry standard. Bagley made a fortune and helped make Detroit a leader in the manufacture of tobacco products.

At the turn of the twentieth-century, the tobacco industry employed many young women--mostly Polish immigrants. In 1913, the ten largest Detroit tobacco companies employed 302 men and 3,896 women, making the cigar industry the largest employer of women in the city. The process of hand rolling cigars was labor intensive and involved some skill. Too tight and the cigar would not draw properly, too loose and the cigar fell apart. Although women were not organized into labor unions, they were able to make $25 to $40 a week. That was a good wage a hundred years ago.

A cigar company sit-down strike.On June 26, 1916, Detroit's San Telmo Company signed a contract with its unionized male cigar makers giving them a significant pay increase. The women wanted equal pay for equal work. Three days later, women at the Lilies Cigar Company walked off the job. Soon there were strikes shutting down all the major Detroit cigar producers. Through their united action, women workers achieved some of their demands.

A cigar company sit-down strike.On June 26, 1916, Detroit's San Telmo Company signed a contract with its unionized male cigar makers giving them a significant pay increase. The women wanted equal pay for equal work. Three days later, women at the Lilies Cigar Company walked off the job. Soon there were strikes shutting down all the major Detroit cigar producers. Through their united action, women workers achieved some of their demands.

The center of the tobacco industry remained in the North until the 1920s. When Prohibition went into effect with the passage of the nineteenth amendment in 1920, the major marketplace for cigars--saloons and hotel bars--were closed and the social patterns of America were shaken.

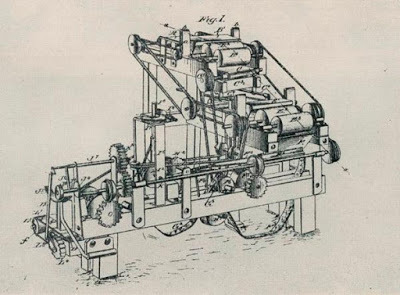

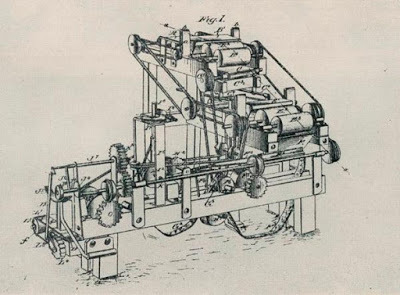

Patent office drawing of automatic cigarette making machine.But the writing was on the wall for Detroit's cigar and tobacco industry. The invention of the automatic cigarette rolling machine in 1881 reduced demand for cigars and other tobacco products. James Albert Bonsack's machine was patented and installed throughout many Southern states causing a shift in the tobacco industry away from the North. Inexpensive mass-produced cigarettes were all the rage in the fast approaching twentieth century. Detroit's ambition shifted too--towards the automobile business which would revolutionize the new century.

Patent office drawing of automatic cigarette making machine.But the writing was on the wall for Detroit's cigar and tobacco industry. The invention of the automatic cigarette rolling machine in 1881 reduced demand for cigars and other tobacco products. James Albert Bonsack's machine was patented and installed throughout many Southern states causing a shift in the tobacco industry away from the North. Inexpensive mass-produced cigarettes were all the rage in the fast approaching twentieth century. Detroit's ambition shifted too--towards the automobile business which would revolutionize the new century.

In 1966, the last cigar manufacturer in Detroit--Schwartz-Wemmer-Gilbert--closed its doors. Detroit was once home to thirty-eight tobacco companies.

Another German dominated industry in Detroit was the brewing of beer. Here is the story of the Strohs family: http://fornology.blogspot.com/2015/02/detroits-strohs-brewing-company-with.html

Only four years after becoming a state, the tobacco industry in Michigan got its start when George Miller became the first tobacconist in the city of Detroit in 1841. By the 1850s--with the help of New York's Erie Canal--many Germans migrated to Detroit. These Germans enjoyed smoking and knew how to produce excellent cigars; soon they dominated the city's industry.

Raw material was nearby in Southwestern Ontario. The Canadians produced a high-quality tobacco crop in sandy and silt-loam soil. With tobacco so close at hand, demand for Detroit's quality wrapped cigars turned a cottage industry into an early form of mass production employing thousands of workers throughout the Detroit area.

Long before Henry Ford's assembly-line, the cigar industry deconstructed the rolling of cigars into specialized tasks. Each worker performed one part of the process, so few people had the skill to make a whole cigar. Baskets or crates of cigars were moved from station to station down long tables. The process was efficient and Detroit cigars became known for their consistent quality.

Long before Henry Ford's assembly-line, the cigar industry deconstructed the rolling of cigars into specialized tasks. Each worker performed one part of the process, so few people had the skill to make a whole cigar. Baskets or crates of cigars were moved from station to station down long tables. The process was efficient and Detroit cigars became known for their consistent quality. Then came the American Civil War and the soldier's high demand for tobacco products. To the Yankee or Rebel soldier, tobacco represented the convenience and consolation of home. The hand-rolled cigarette was still an item of luxury, but the cigar represented victory, and the pipe comfort and solace. Soldiers North and South often relaxed by chomping on rich, gooey plugs of chewing tobacco or by smoking delicate clay pipes before, during, and after battles. Much of this tobacco was processed and packaged in Detroit.

Sixteenth governor of the State of Michigan (1873-1877) John Judson Bagley moved to Detroit in 1847. In his early twenties, he started his working career as a humble apprentice in a small chewing tobacco shop. After seven years, he bought the business and renamed it Mayflower Tobacco Company turning his company into an industry leader. Bagley manufactured a rectangular form of chewing tobacco in a tin with a friction-fitted lid that became an industry standard. Bagley made a fortune and helped make Detroit a leader in the manufacture of tobacco products.

Sixteenth governor of the State of Michigan (1873-1877) John Judson Bagley moved to Detroit in 1847. In his early twenties, he started his working career as a humble apprentice in a small chewing tobacco shop. After seven years, he bought the business and renamed it Mayflower Tobacco Company turning his company into an industry leader. Bagley manufactured a rectangular form of chewing tobacco in a tin with a friction-fitted lid that became an industry standard. Bagley made a fortune and helped make Detroit a leader in the manufacture of tobacco products.At the turn of the twentieth-century, the tobacco industry employed many young women--mostly Polish immigrants. In 1913, the ten largest Detroit tobacco companies employed 302 men and 3,896 women, making the cigar industry the largest employer of women in the city. The process of hand rolling cigars was labor intensive and involved some skill. Too tight and the cigar would not draw properly, too loose and the cigar fell apart. Although women were not organized into labor unions, they were able to make $25 to $40 a week. That was a good wage a hundred years ago.

A cigar company sit-down strike.On June 26, 1916, Detroit's San Telmo Company signed a contract with its unionized male cigar makers giving them a significant pay increase. The women wanted equal pay for equal work. Three days later, women at the Lilies Cigar Company walked off the job. Soon there were strikes shutting down all the major Detroit cigar producers. Through their united action, women workers achieved some of their demands.

A cigar company sit-down strike.On June 26, 1916, Detroit's San Telmo Company signed a contract with its unionized male cigar makers giving them a significant pay increase. The women wanted equal pay for equal work. Three days later, women at the Lilies Cigar Company walked off the job. Soon there were strikes shutting down all the major Detroit cigar producers. Through their united action, women workers achieved some of their demands.The center of the tobacco industry remained in the North until the 1920s. When Prohibition went into effect with the passage of the nineteenth amendment in 1920, the major marketplace for cigars--saloons and hotel bars--were closed and the social patterns of America were shaken.

Patent office drawing of automatic cigarette making machine.But the writing was on the wall for Detroit's cigar and tobacco industry. The invention of the automatic cigarette rolling machine in 1881 reduced demand for cigars and other tobacco products. James Albert Bonsack's machine was patented and installed throughout many Southern states causing a shift in the tobacco industry away from the North. Inexpensive mass-produced cigarettes were all the rage in the fast approaching twentieth century. Detroit's ambition shifted too--towards the automobile business which would revolutionize the new century.

Patent office drawing of automatic cigarette making machine.But the writing was on the wall for Detroit's cigar and tobacco industry. The invention of the automatic cigarette rolling machine in 1881 reduced demand for cigars and other tobacco products. James Albert Bonsack's machine was patented and installed throughout many Southern states causing a shift in the tobacco industry away from the North. Inexpensive mass-produced cigarettes were all the rage in the fast approaching twentieth century. Detroit's ambition shifted too--towards the automobile business which would revolutionize the new century.In 1966, the last cigar manufacturer in Detroit--Schwartz-Wemmer-Gilbert--closed its doors. Detroit was once home to thirty-eight tobacco companies.

Another German dominated industry in Detroit was the brewing of beer. Here is the story of the Strohs family: http://fornology.blogspot.com/2015/02/detroits-strohs-brewing-company-with.html

Published on December 26, 2016 07:02

December 12, 2016

Ypsilanti's Hutchinson House Built with S&H Green Stamp Fortune

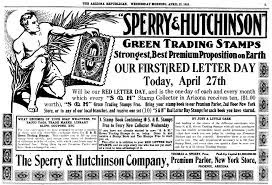

In 1896, Thomas A. Sperry and Shelley Byron Hutchinson went into the S&H Green Stamp business together. The New York Times business section described this newly formed company "the first independent trading stamp company to distribute stamps and books to merchants."

In 1896, Thomas A. Sperry and Shelley Byron Hutchinson went into the S&H Green Stamp business together. The New York Times business section described this newly formed company "the first independent trading stamp company to distribute stamps and books to merchants."Not much is known about Mr. Sperry. He was an Easterner. His home was destroyed by fire in 1912, with damages estimated to be $150,000. He was an avid art collector and a number of valuable paintings went up in flames. A year later, Sperry contracted ptomaine poisoning on a return ocean cruise from Europe. When he returned to the United States, he was so ill he couldn't travel to his home in Cranford, New Jersey. He was forty-nine years old when he died.

Sperry's brother, William Miller Sperry, inherited his brother's business interests and gained control of the company. In 1921, Shelley Hutchinson sued the estate of Thomas A. Sperry alleging that Sperry defrauded him of his full share of dividends to the tune of $5,000,000. Secret funds were diverted from company funds to Sperry. Hutchinson won the suit. The founders' family successors sold the franchise in 1981.

Much more in known about Shelley Hutchinson. His grandparents were among the first settlers in Ypsilanti, Michigan, still little more than a frontier outpost. Shelley's father Stephen Hutchinson married Loretta Jaycox on November 26, 1862. Shelley was born two years later in a log cabin in Superior Township on October 19, 1864. From 1874 until 1894, the Hutchinsons lived in a four room wood frame house at 509 N. River Street, across the street from the Champlain mansion. As a kid, he attended the Union School through the eighth grade--a typical education for a nineteenth-century boy.

Shelley was ambitious and intelligent. While working at a family shoe business with his father and brother in Battle Creek, Michigan, in the 1880s, he conjured up the idea for a trading stamp business he could promote to merchants as a customer retention program. On a small scale, the idea was promising, so a regional headquarters was established in Jackson, Michigan, chosen for its central location between the state's eastern and western borders.

Three years later, Hutchinson met Sperry in New York--an Easterner with money and business connections. Soon after they went into business, stamp redemption centers sprung up in many of Michigan's major cities. With early success, the promotion was expanded eventually growing into a nationwide coast-to-coast business concern. Sperry and Hutchinson made money hand over fist.

Shelley Hutchinson met Clara Unsinger, who was a stenographer in the company. Clara was the granddaughter of an Ypsilanti deacon. They were married on April 27, 1894. By the turn of the century, Hutchinson had amassed enough money to build his dream house. He considered building in New York, but his father urged him to build in Ypsilanti to be reunited with family and friends.

Feeling a boyhood affinity for the area, Hutchinson decided to build his thirty-room Richardsonian Revival mansion across the street from where he grew up--the site of the deteriorating Champlain mansion on the corner of North River and East Forest streets. Construction began in 1902 and was completed in 1904. Hutchinson called his mansion Casa Loma--Spanish for house on the hill. The site was believed to be Ypsilanti's highest point--on the east side anyway. He moved in with his wife, three children, parents, and brothers and sisters.

See the link below for more views of the house.

See the link below for more views of the house.Building his mansion on Ypsilanti's east side was a social mistake for the wealthy millionaire. The Huron River was the town's dividing line. The east side was the working class neighborhood, and the west side was primarily for the wealthy and social elite. Hutchinson was never accepted into Ypsilanti high society because he was "new money" and shunned the "old money" denizens. He and his wife Clara rode around town in a fine phaeton carriage with matching horses. The newly rich pair wore only the finest clothes, and the "Stamp King" wore a silk top hat. During the height of his success, Hutchinson bought diamonds by the pocketful from Tiffany's in New York.

In an early undated Ypsilanti Daily Press article, the reporter wrote a "rags to riches" story about Hutchinson. Quoting merchant A.A. Bedell, "Hutchinson was always immaculate in dress, dark haired and handsome. One day, he stood in (my shoe store in Depot Town) and a shaft of light struck his diamonds, a glittering array. He had half-caret diamonds in each cuff link and wore two diamond rings, one of three carets and one between seven and eight. His shirt stud had a three and a half-caret stone." People said when Hutchinson walked in the sunshine, he sparkled.

But the domestic situation at Casa Loma was less than stellar. The Detroit News reported on July 3, 1906, that Mrs. Hutchinson deserted "the mansion on the hill" in anger taking her three children with her to live with neighbors across the street at 629 N. River Street. Clara had had it with her Hutchinson inlaws and complained to the reporter that she was forced from her home penniless--except for some diamonds she left with. Hutchinson's father and sister publically claimed they wished Clara would return to manage the place. As for her husband, Shelley retreated and went south for his health. The domestic situation was intolerable for him too.

As the story goes, Shelley had been gravely ill and entrusted his wife with his diamonds. Upon recoverery, he asked for them back. Clara refused saying he gave them to her. She hid the diamonds away, but while she was sleeping one night, her husband found her hiding place. Shelley locked the diamonds in a tin box and placed them in his roll-top desk in his locked home office. Two could play at that game. Clara took her husband's key and unlocked the office door. After a brief search, she found the tin box and opened it with a can opener. Then she left the mansion taking her children.

The Ypsilanti Daily Press reported on January 14, 1910, that a divorce was granted giving Clara custody of the three children, $9,000 cash paid out over five years, and her husband's diamonds. She sold the largest one to a neighbor and the rest to a diamond broker in Detroit. In 1912, Hutchinson's mansion was sold at public auction to the Ypsilanti Savings Bank to satisfy an unpaid mortgage and back taxes. The home is now used for a commercial property and houses several businesses.

In an Ypsilanti Press interview in 1955, the ninety-one-year-old Hutchinson was living in New York. He was quoted as saying, "Some of the people (in Ypsilanti) were jealous of me because of the big house, but they had no reason to be. I was good to everybody." Shelley Hutchinson returned to Ypsilanti one last time time in 1961 for burial in a family plot at Highland Cemetery--several blocks north of his mansion. He was ninety-seven.

Most people in Ypsilanti are familiar with the outside of the Hutchinson House but have never seen the interior. Check out this link to see just how extravagant it is. https://www.flickr.com/photos/sjb4photos/sets/72157622572604360/

For more detailed information about the Hutchinson family, read Janice Anschuetz's article "River Street Neighbor's Gossip and the Hutchinson Marriage," which appeared in the Ypsilanti Historical Society's September 27, 2010, newsletter Ypsilanti Gleanings. http://ypsigleanings.aadl.org/ypsigleanings/37044

Published on December 12, 2016 07:02

December 5, 2016

S&H Green Stamps--Emblem of a Bygone Age

Sperry and Hutchinson Company were the originators of S&H Green Stamps, as much an American cultural icon as anything. The company began offering redemption stamps to American retailers in 1896. Stores bought the stamps and offered them as bonuses based on the dollar amount of the purchase. S&H Green Stamps was the earliest retail customer loyalty program selling and distributing stamps and books to merchants. With a unidirectional cash flow, this shoppers' incentive made its originators multi-millionaires.

Sperry and Hutchinson Company were the originators of S&H Green Stamps, as much an American cultural icon as anything. The company began offering redemption stamps to American retailers in 1896. Stores bought the stamps and offered them as bonuses based on the dollar amount of the purchase. S&H Green Stamps was the earliest retail customer loyalty program selling and distributing stamps and books to merchants. With a unidirectional cash flow, this shoppers' incentive made its originators multi-millionaires. Stamps were issued in denominations of 1, 10, and 50 points. Stamp pages were perforated with glue on the reverse side to mount in twenty-four page collector booklets. Each booklet contained 1,200 points. Reward gifts were based on the number of filled books required to obtain the object. Green Stamps had no real cash value.

Stamps were issued in denominations of 1, 10, and 50 points. Stamp pages were perforated with glue on the reverse side to mount in twenty-four page collector booklets. Each booklet contained 1,200 points. Reward gifts were based on the number of filled books required to obtain the object. Green Stamps had no real cash value. S&H Green Stamps could be obtained at supermarkets, department stores, and gas stations. Completed booklets could be redeemed at one of 800 distribution centers located around the country. Most popular in the early 1960s, S&H boasted that its reward catalog was the largest publication in the United States. They issued three times more stamps than the United States Postal Service.

S&H Green Stamps could be obtained at supermarkets, department stores, and gas stations. Completed booklets could be redeemed at one of 800 distribution centers located around the country. Most popular in the early 1960s, S&H boasted that its reward catalog was the largest publication in the United States. They issued three times more stamps than the United States Postal Service.Economic recessions in the 1970s reduced sales and decreased the value of the rewards. Shoppers began to see the stamps as not worth the trouble, and stores started to drop out of the program. In 1981, the founders' successors sold the business.

Green Stamps entered the realm of pop art iconography when Andy Warhol used a three step silkscreen process to print a 23"x22.75" canvas in 1962. Three years later, he used offset lithography to print the classic green stamp images on forty-nine 7'x7' panels to act as wallpaper within a gallery exhibit at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in Philadelphia. A single panel recently sold at auction for $6,250.

S&H Green Stamp founders Thomas Sperry and Shelly Byron Hutchinson are the subject of my next post. Hutchinson was from Ypsilanti, Michigan, and became the town's richest self-made man.

To have my Fornology posts sent to you automatically, subscribe at the top of the right hand sidebar.

Published on December 05, 2016 08:02

November 25, 2016

Little Richard Streicher--Ypsilanti's Depression Era Unsolved Murder

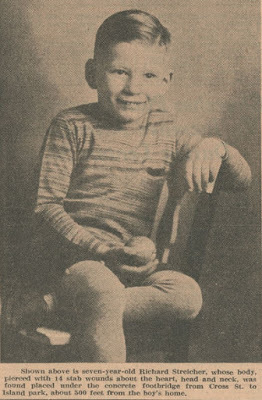

On the blustery afternoon of March 8, 1935, thirteen-year-old Buck Holt and his eleven-year-old brother Billy followed muskrat tracks in the snow and discovered the body of seven-year-old Richard Streicher, Jr., missing since the previous evening. He was found frozen solid under the footbridge leading to Island Park [now called Frog Island], adjacent to the Cross Street bridge spanning the Huron River.

On the blustery afternoon of March 8, 1935, thirteen-year-old Buck Holt and his eleven-year-old brother Billy followed muskrat tracks in the snow and discovered the body of seven-year-old Richard Streicher, Jr., missing since the previous evening. He was found frozen solid under the footbridge leading to Island Park [now called Frog Island], adjacent to the Cross Street bridge spanning the Huron River.Buck Holt ran to the Anderson Service Station [gas station] across the street and told attendant Raymond Deck (22) there was a dead kid down there. Deck investigated and immediately phoned the Ypsilanti police. Chief Ralph Southard was the first to arrive, followed shortly by Washtenaw County Deputy Sheriff Richard Klavitter, and his brother Sergeant Ernest Klavitter of the Ypsilanti police.

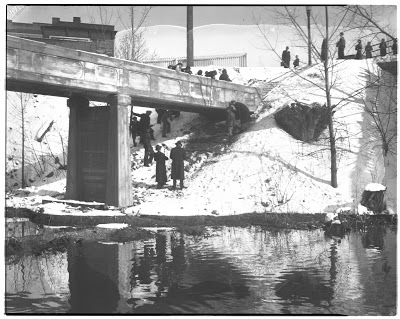

Scene under the footbridge where Streicher's body was discovered.By the time police arrived, a crowd of curious bystanders had trampled any footprint evidence left in the overnight snow. To further complicate matters, a bucket of sand was spread on the snow to make it safer for investigators to climb down the slope to view the body. The shovel used to spread the sand was used to pry Richard Streicher from the cement ledge he was frozen onto. Then the body was taken to the Moore Funeral Home in Ypsilanti to thaw. Richard Streicher's stiff clothes were cut from his body and burned at the request of his parents. More potential evidence was destroyed.

Scene under the footbridge where Streicher's body was discovered.By the time police arrived, a crowd of curious bystanders had trampled any footprint evidence left in the overnight snow. To further complicate matters, a bucket of sand was spread on the snow to make it safer for investigators to climb down the slope to view the body. The shovel used to spread the sand was used to pry Richard Streicher from the cement ledge he was frozen onto. Then the body was taken to the Moore Funeral Home in Ypsilanti to thaw. Richard Streicher's stiff clothes were cut from his body and burned at the request of his parents. More potential evidence was destroyed.The autopsy was done at the funeral home rather than a medical facility. Of fourteen knife wounds, three punctured the wall of the heart causing his death. A good-faith police investigation--by Depression era standards--was conducted. Seven months later, Richard Streicher's body was exhumed, with a second autopsy performed by the county coroner's office.

On September 27, 1937, a one-man grand jury was conducted by State Attorney General Raymond W. Starr. He took another look into the case and interviewed close to forty people, but no new evidence was disclosed. The result--nobody charged--nobody indicted. The case remains unsolved over eighty years later.

Richard Streicher, Jr. was buried in Highland Cemetery [Section 16 - Lot 66], but nobody in living memory can say if his grave site ever had a marker or headstone. It has been unmarked for decades. Perhaps someone misplaced the headstone when Richard's body was exhumed. More likely--someone removed it for a macabre souvenir. Nobody knows.

Last year, an article about Richard Streicher, Jr. by John Counts for MLive [December 27, 2015] moved John Sisk, Jr. to start a Go Fund Me page to raise money for a gravestone. With the help of Robison-Bahnmiller Funeral Home in Saline, Michigan, Tina Atkinson-Kalusha of Highland Cemetery, and private donations, a monument was designed to honor the memory of little Richard Streicher. A nineteenth-century sled is engraved in the granite headstone. Richard was last seen alive sledding with friends. A graveside memorial service was held on Saturday, October 15, 2016.

Last year, an article about Richard Streicher, Jr. by John Counts for MLive [December 27, 2015] moved John Sisk, Jr. to start a Go Fund Me page to raise money for a gravestone. With the help of Robison-Bahnmiller Funeral Home in Saline, Michigan, Tina Atkinson-Kalusha of Highland Cemetery, and private donations, a monument was designed to honor the memory of little Richard Streicher. A nineteenth-century sled is engraved in the granite headstone. Richard was last seen alive sledding with friends. A graveside memorial service was held on Saturday, October 15, 2016.If any of my Ypsilanti readers happen upon Richard's grave in Highland Cemetery, say a prayer for the little guy who deserved better than he got.

John Count's MLive Richard Streicher article: http://www.mlive.com/news/ann-arbor/index.ssf/2015/12/ypsilanti_boys_murder_80_years.html

Published on November 25, 2016 05:00

November 10, 2016

America Plays Its Trump Card

Respect the presidency regardless of who holds the office. Whether you like Trump or not, he will soon be our president. Either support him or become part of the loyal opposition. As Americans, those are our only viable choices.

Denying reality is not an option and neither is cutting-and-running. We are all bound up in this moment of history together.

In Hoc Signo Vinces.

Published on November 10, 2016 06:34