Deborah J. Ross's Blog, page 157

October 8, 2011

Sword & Sorceress 26 Interview

Jonathan Moeller interviews me on my story, "The Seal Hunt," in the forthcoming Sword & Sorceress 26. I talk about epublishing, whether it's good for readers as well as writers, and a bunch of other cool stuff.

"The Seal Hunt" came from the same utterly unworkable attempt-at-a-novel that "The Casket of Brass" (S & S 24) did. Each one then underwent quite a lot of re-working so that it could stand on its own. In the process, my heroine, Tabitha, really took shape. I've never written a character quite like her, a sort of fantasy-world/scholar/Sherlock Holmes who uses keen observation and rapier intelligence to solve mysteries. I'd pit her wits against any evil sorcerer!

Here's the whole thing: http://www.jonathanmoeller.com/writer...

"The Seal Hunt" came from the same utterly unworkable attempt-at-a-novel that "The Casket of Brass" (S & S 24) did. Each one then underwent quite a lot of re-working so that it could stand on its own. In the process, my heroine, Tabitha, really took shape. I've never written a character quite like her, a sort of fantasy-world/scholar/Sherlock Holmes who uses keen observation and rapier intelligence to solve mysteries. I'd pit her wits against any evil sorcerer!

Here's the whole thing: http://www.jonathanmoeller.com/writer...

Published on October 08, 2011 10:53

October 6, 2011

A Steve Jobs connection

I never met Steve Jobs, at least not that I knew of. If our paths crossed at Reed College, I never knew who he was. I've never owned an Apple computer, so I have no connection with him that way. Yet we share a deeper experience. We both had the honor and delight to study calligraphy at Reed College. (I believe Jobs actually studied with Bob Palladino, Lloyd's student and successor, who continued his tradition.)

Here's what Jobs said in his 2005 Commencement address at Stanford University:

I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and san serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can't capture, and I found it fascinating. None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But 10 years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me. And we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography.

When I heard about his death, one of my thoughts was, Another person who knew Lloyd is gone. And since lots and lots of other people are talking about the impact Jobs and Apple made in their lives, I want to talk a little about Lloyd.

When I heard about his death, one of my thoughts was, Another person who knew Lloyd is gone. And since lots and lots of other people are talking about the impact Jobs and Apple made in their lives, I want to talk a little about Lloyd.

A calligraphy class -- any class -- with Lloyd encompassed far more than the subject material. Yes, he taught us about letter forms, their evolution and design, and how the demands of the eye and the inherent rhythms of the hand shape the letter forms. But more than that, Lloyd taught us to see and to listen beneath the obvious. Into his lectures, he wove Buddhist philosophy, William Blake, John Ruskin, contemporary progressive thought, and a deep and abiding reverence for the many expressions of the human spirit. He railed against narrow-mindedness, bigotry, hatred (and stood up to HUAC during the McCarthy years).

He loved to make writing organic, writing poems on brown paper and hanging them on trees; he called them "weathergrams."

He loved to make writing organic, writing poems on brown paper and hanging them on trees; he called them "weathergrams."

In this video, notice how the energy of Mozart's music flows through the movement of the pen. Also, the fluidity of the strokes, which comes from a soft grasp of the pen and suppleness through the entire arm and body. The pen dances across the pages.

Here's another clip from the series on italic calligraphy he taught for Oregon Public Television. (Through YouTube, you can also find others.)

Here's what Jobs said in his 2005 Commencement address at Stanford University:

I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this. I learned about serif and san serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great. It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can't capture, and I found it fascinating. None of this had even a hope of any practical application in my life. But 10 years later, when we were designing the first Macintosh computer, it all came back to me. And we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography.

When I heard about his death, one of my thoughts was, Another person who knew Lloyd is gone. And since lots and lots of other people are talking about the impact Jobs and Apple made in their lives, I want to talk a little about Lloyd.

When I heard about his death, one of my thoughts was, Another person who knew Lloyd is gone. And since lots and lots of other people are talking about the impact Jobs and Apple made in their lives, I want to talk a little about Lloyd.A calligraphy class -- any class -- with Lloyd encompassed far more than the subject material. Yes, he taught us about letter forms, their evolution and design, and how the demands of the eye and the inherent rhythms of the hand shape the letter forms. But more than that, Lloyd taught us to see and to listen beneath the obvious. Into his lectures, he wove Buddhist philosophy, William Blake, John Ruskin, contemporary progressive thought, and a deep and abiding reverence for the many expressions of the human spirit. He railed against narrow-mindedness, bigotry, hatred (and stood up to HUAC during the McCarthy years).

He loved to make writing organic, writing poems on brown paper and hanging them on trees; he called them "weathergrams."

He loved to make writing organic, writing poems on brown paper and hanging them on trees; he called them "weathergrams." In this video, notice how the energy of Mozart's music flows through the movement of the pen. Also, the fluidity of the strokes, which comes from a soft grasp of the pen and suppleness through the entire arm and body. The pen dances across the pages.

Here's another clip from the series on italic calligraphy he taught for Oregon Public Television. (Through YouTube, you can also find others.)

Published on October 06, 2011 11:47

October 3, 2011

Writing Thought of the Day

"No one else in the wide world, since the dawn of time, has ever seen the world as you do, or can explain it as you can. This is what you have to offer that no one else can. Nobody can know how good you are unless you risk letting them know how bad you might be." -- Edith Laydon

"No one else in the wide world, since the dawn of time, has ever seen the world as you do, or can explain it as you can. This is what you have to offer that no one else can. Nobody can know how good you are unless you risk letting them know how bad you might be." -- Edith LaydonThe painting is Brace's Rock, Brace's Cove, 1864, by Fitz Hugh Lane (1804-1865), in the public domain.

Published on October 03, 2011 17:56

October 2, 2011

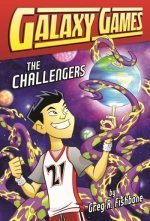

GUEST BLOG: Writing SF for Young Readers by Greg R. Fishbone

I met Greg R. Fishbone at Launch Pad 2011. He's the author of middle-grade science fiction, and I think what he has to say about writing for kids applies to writing for all readers. Kids, after all, love good stories as much as anyone does, but they tolerate pretentious writing far less. Keep us honest, they do.

I met Greg R. Fishbone at Launch Pad 2011. He's the author of middle-grade science fiction, and I think what he has to say about writing for kids applies to writing for all readers. Kids, after all, love good stories as much as anyone does, but they tolerate pretentious writing far less. Keep us honest, they do.

During the month of October, Greg will be popping up all over the Internet to talk about writing, humor, and The Challengers, the first book in his Galaxy Games series. http://galaxygamesseries.com Here's the fun part: he's set up a sort of puzzle/treasure hunt. Read on, and you'll find Puzzle Piece #2 of 31. More information on the contest is here.

Take it away, Greg!

There are two parts to writing science fiction for young readers: the science fictiony part and the young readery part. I know this sounds obvious, but bear with me. Writing science fiction requires knowledge of the genre and its conventions while writing for young readers requires a set of style sensibilities that's entirely different from writing for adults.

I've seen some great midgrade or YA authors stumble through their first attempt at genre fiction. Some of them apply science fiction trappings to a traditionally terrestrial plot, mostly by making up funny names that don't have any world-building logic behind them. As a result, their work may look something like this:

Plzzmar gripped his flarf-o-mat in one hand and his blixoschmabbit in the other as he looked out across the Spzzmaxian Plains at the Raxmaxthth Mountains on Planet Blrtzlgraghmontyockt. "Drzttgalkjfald," Plzzmar swore, in the Fggdfafrdaxit dialect of Crzztmathgaxian that he'd picked up during his latest mission aboard Starship Jadfadfabadfadglkj.

Yes, there tend to be strangely-named people, places, and things in stories that involve alien worlds and futuristic technologies, but that doesn't give you license to mash your fingers on the keyboard and call it vocabulary. Names in your story should be internally consistent, make sense for the culture or cultures that you are depicting, and be at least somewhat pronounceable. You need to adequately define your terms for the reader, hopefully by context rather than by exposition. And if you are describing an object that could be several generations removed from a familiar object the readers already know, consider using some variation of the more common name.

A machine that creates gourmet meals-on-the-go in exchange for credits is still just a vending machine. If it pulls the orders directly out of a user's thoughts, the manufacturer might put the machine into a generic "psycho-activated meal vender" or "press-free meal vender" product category to distinguish it from the push-button version. The marketing department might dub it the "Thought Chef 4G" or "Mecha-Emeril." And finally, your character might come up with a snarkily disparaging nickname like "Puke Spew 4G" or "Mecha Garbage Dispenser." Calling it a "Vend-o-Tron" or "Food-o-Mat" will only make people think you've freshly arrived from the 1950s, when those terms still sounded futuristic.

Writers who are new to science fiction may also underestimate the importance of getting the science right. Not right like a textbook but right as in plausible, given the things we're pretty sure about, the gaps where our current knowledge is incomplete, the author's logical extrapolations made in good faith, the needs of a good story, and general reader expectations. Einstein claimed that faster-than-light travel is impossible and he hasn't been proven wrong yet, but FTL-ships are entrenched in the genre by decades of tradition. Readers have come to accept planet-hopping starships as a science fiction convention because they are a necessary device to enables a huge subset of stories. Plus, with all we're still learning about the fine structure of the universe, it's still possible that Einstein will be overturned in some special case that will make ships like these possible. An author gets some latitude when you're dealing with a topic on the cutting edge of science, but you'd better not flub the basic stuff without good reason.

Things can also go wrong when folks who are used to writing science fiction for adults take a stab at the young adult or middle grade market--without changing their style or voice. Interesting as the premise of your adult-oriented novel may be, you usually can't just drop the protagonist's age, remove the explicitly adult material, and call it children's literature. For one thing, your adult-oriented novel is likely to be 50,000 to 100,000 words too long--and allow me to cut you off before you begin a protest with, "But kids loved that 9,000-page Harry Potter novel..." J.K. Rowling had to establish herself specifically as not like the rest of us before her publisher let her release a middle-grade book of that length.

Your adult-oriented writing likely contains adult-oriented bloat: slow, mood-establishing exposition; detailed descriptions of landscapes, room furnishings, and fashion accessories; meandering plotlines; superfluous subplots, and dialog that doesn't advance the story. Adults will slog through and applaud your fine literary style, but Kids won't put up with any of it. And if you lose your readers on Page 1, you've lost them forever. For young readers, you need appropriate pacing, linear storytelling, a kid-friendly voice, and a protagonist who is actively involved in resolving the plot. You will also need to spotlight some of the themes young readers care about most: family, friends, school, relationships, and the challenges of entering the adult world.

Good science fiction requires world-building, respect for science, and attention to detail. Good fiction for young readers requires age-appropriate structure, voice, and theme. Good science fiction for young readers will require all of the above.

Ready for that Puzzle Piece?

If you enjoyed Greg's blog, pop over to the Galaxy Games site and leave him a note! Also let me know if you want to see more Guest Posts.

Published on October 02, 2011 01:00