Deborah J. Ross's Blog, page 149

April 6, 2012

Robert Silverberg on learning to write

Another wonderful article from SF Signal is this interview with Robert Silverberg bu Bryan Thomas Schmidt. Silverberg talks about specific works (like Lord Valentine's Castle) and that's interesting, but for me the prize was what he says about learning to write. He encapsulates my experience as well:

I never have taken a writing course, and don't recommend them.

Occasionally I would read a book about writing, like Thomas Uzzell's Narrative Technique,

but usually came away baffled. I learned my craft by reading an

infinite amount of fiction and trying to discover how the authors

achieved their effects. Where to begin a story? How does one end one?

How much dialog should be mixed with exposition? I figured it all out

by the time I was sixteen or so. I was a quick learner. The problem

was not so much to learn the craft of telling a story as to learn enough

about the real world so that one had stories to tell.

I, on the other hand, am a slow learner, and I'm still working on figuring it out. But knowing how to put down one word after another is only the mechanics of the craft. If I were to give advice to a young writer, I'd say, Don't study writing. Take classes in history, anthropology, religion, astronomy, biology, economics, sculpture, physics. Play a musical instrument, even if badly. Volunteer at a soup kitchen. Go hiking in the highest mountains you can find. Learn a new language, preferably one that uses a different alphabet. Talk to people with whom you disagree, and listen to them, to the experiences behind the rhetoric. Study calligraphy and the history of writing. Dance under the stars. Fall in love, and get your heart broken. Learn to ride a horse (or a camel, or an elephant). In other words, Have something to write about. And read. Read widely and exuberantly. Read stuff that makes you furious and exhilarated and bored and sorrowful - and examine the why and how.

It would be a fascinating exercise to read Silverberg's novels in the order they were written, to watch the development of his craft. And besides, he loves museums and dinosaurs, so what more can one want?

I never have taken a writing course, and don't recommend them.

Occasionally I would read a book about writing, like Thomas Uzzell's Narrative Technique,

but usually came away baffled. I learned my craft by reading an

infinite amount of fiction and trying to discover how the authors

achieved their effects. Where to begin a story? How does one end one?

How much dialog should be mixed with exposition? I figured it all out

by the time I was sixteen or so. I was a quick learner. The problem

was not so much to learn the craft of telling a story as to learn enough

about the real world so that one had stories to tell.

I, on the other hand, am a slow learner, and I'm still working on figuring it out. But knowing how to put down one word after another is only the mechanics of the craft. If I were to give advice to a young writer, I'd say, Don't study writing. Take classes in history, anthropology, religion, astronomy, biology, economics, sculpture, physics. Play a musical instrument, even if badly. Volunteer at a soup kitchen. Go hiking in the highest mountains you can find. Learn a new language, preferably one that uses a different alphabet. Talk to people with whom you disagree, and listen to them, to the experiences behind the rhetoric. Study calligraphy and the history of writing. Dance under the stars. Fall in love, and get your heart broken. Learn to ride a horse (or a camel, or an elephant). In other words, Have something to write about. And read. Read widely and exuberantly. Read stuff that makes you furious and exhilarated and bored and sorrowful - and examine the why and how.

It would be a fascinating exercise to read Silverberg's novels in the order they were written, to watch the development of his craft. And besides, he loves museums and dinosaurs, so what more can one want?

Published on April 06, 2012 10:09

April 5, 2012

Celebrating George R. R. Martin

John DeNardo posts on Kirkus Reviews about the books George R. R. Martin wrote before "Game of Thrones." He points out, quite rightly, that Martin was already an established author and editor, respected in science fiction, well before his work broke big. I won't repeat this list of his achievements here -- you can go read DeNardo. My personal revelation after reading the article was, "Oh thank goodness, I'm not the only one who loved Martin's work, gave up on "Game of Thrones," and hope Martin returns to writing stuff I can read." Not that DeNardo said that (he didn't), but that I no longer feel I have to justify myself.

I think the first of Martin's books I read was Windhaven (1981), co-written with the amazing and wonderful Lisa Tuttle. (And if you don't know her work, you should immediately seek it out.) It was good solid science fiction, full of action yet thoughtful, and as a woman reading it in the early 1980s, the heroine who wanted to fly spoke right to me. The book marked both authors as "look out for their work." Then followed (not in publication order, in reading order) was Fevre Dream. Steamboats and suitably scary vampires, not the current angsty sparkly kind. Think gothic, think Mississippi River in late 1850s, think seriously creepy.

I've read other work by Martin, but the one that lingers in my mind was his first published book, Dying of the Light (1977).

"Game of Thrones," on the other hand, simply didn't work for me. Or rather, the first book and a chapter didn't work for me. Characters I really don't want to read about, getting ripped out of every interesting story line time and again... just about the only thing I cared about was the dire wolves, and them only because my ex used to volunteer at the Page Museum (La Brea tarpits) in LA. And those were way cooler than Martin's wolves. Sigh.

Now I am reminded that I can enthuse of Martin's work and simply ignore all the hoo-hah about the ones I don't like. What, you like "Game of Thrones" -- great! There's more than enough cool stuff to go around. I'll stick with Dying of the Light and Fevre Dream.

Published on April 05, 2012 11:54

April 3, 2012

Let's Hear It For Short Stories!

I grew up with a love-hate relationship with short fiction. Having to read short stories in school almost ruined

I grew up with a love-hate relationship with short fiction. Having to read short stories in school almost ruinedthem for me. Actually, the reading was fine; it was the having to

answer the brain-dead, pointless, intellectually insulting questions

about those stories that made me want to throw the books across the

classroom. I had no idea what criteria the textbook authors were using,

but if this was what short fiction was about, I could not understand why

anyone would voluntarily read it.

And yet, as soon as I got a

And yet, as soon as I got a library card, I checked out volume after volume of Groff Conklin's

anthologies. I read the few digest magazines in my possession so many

times, I wore them out. I could almost recite some of those stories word

for word. I decided that the field of short fiction was divided into

two parts: the dry, tedious stuff that no one in her right mind would

have anything to do with; and the cool stuff - the stories that grabbed

me right away and swept me into worlds filled with surprises, nifty

ideas, and no-holds-barred excitement. I could indulge myself for an

entire afternoon, or sneak in one of my favorites and still have time to

finish my homework. Although the prose was not of the elevated literary

sort (a good thing, in my opinion) and the characters might be

cardboard supporting actors for the above-mentioned Incredibly Nifty

Ideas And Situations (I didn't care), these stories got the most

important things right. They didn't muck around with showing off the

author's vocabulary; the "point" wasn't dreary and obscure. They were

complete stories, single-minded of purpose, with well-defined

beginnings, middles, and ends, and the characters had actual goals and

perils. These were stories I wanted to read, and hence they were what I

attempted to write.

Two academic degrees and a kid later, I embarked upon a serious writing

career. The conventional wisdom of that time, still held by many, was

that you began by writing short fiction and then "graduated" to novels.

This was supposed to teach you the fundamentals of writing. Short

fiction, you understand, contains all the necessary elements, only in

condensed form, like literary Campbell's Soup. Why anyone thinks it's

easier to make every sentence accomplish three things when in a

novel-length work it has to do only one, I don't know. In this case,

short does not equal simplified. In addition, at that time there were

quite a few markets for short fiction, and new ones popping up all the

time (and disappearing, so it behooved the beginning writer to keep

track of current listings, an art in itself).

It turned out, however, that short stories were no more difficult for me than those of any other length. It was easier

It turned out, however, that short stories were no more difficult for me than those of any other length. It was easierto send off a short story for critique than an entire novel, not to

mention the savings in copying and postage. Having to create a new world

for each story gave me lots of practice. The clincher came when Marion

Zimmer Bradley, with whom I'd been corresponding, told me she was going

to edit an anthology of women's sword and sorcery and would I like to

send her a story, no promises. My fate as a short fiction writer was

sealed.

Print markets for short fiction have come and gone,

editors have come and gone, and yet people persist in reading the darned

things. Clearly, I'm not alone in loving good short fiction. But one of

the enduring challenges has been the ephemeral nature of most magazine

publications. The issue comes out one month and all is rapture and

celebration. A few short weeks later, that issue has been replaced by

the next, and the availability of back issues shrivels rapidly. Unless a

story is reprinted in an anthology, it may be impossible to find (or to

find at a price one can afford for a collector's copy) a decade or two

hence. Those anthologies I loved contained reprints, "The Best Of...",

but these have largely given way largely to originals. (Not that I'm

complaining. I've had the pleasure of editing a number of original

anthologies.)

I think that electronic publishing may be the best

thing to happen to short fiction in a long while. Most of your favorite

authors have backlists of those ephemeral stories. (I say most because

some writers are natural novelists, and they are no less wonderful, they

just don't have long bibliographies of shorter work.) Epublishing is a

great way to make these available again. Shorts are usually priced so a

reader can pick up one or four to explore an author's work without

having to invest a great deal of money.

And

Andshorts still offer the advantage that you can read a whole story in one

sitting. In the airport or doctor's office, on your lunch break, at

bedtime. Just load up a couple of dozen on your ereader and you're set.

Sometimes you want the length and complexity of a novel, to spend

hundreds of pages exploring a world and hanging out with characters who

have become your friends. But other times, you want to jump into a story

and jump out again with the full satisfaction and sense of completeness

that a short story can bring.

At Book View Café, I'm

embarking on an experiment in short fiction publication. Today, I offer

you not one but four for your delectation. Three are fantasy, and one is

science fiction. I had a wonderful time writing each of them, and I

hope you'll enjoy reading them, too.

"Take two, they're small." And only $0.99 each.

Published on April 03, 2012 01:00

March 31, 2012

GUEST BLOG: Frog Jones on The Death (And Re-Birth) of Science Fiction

To continue the discussion about the future of science fiction as a genre, I'm delighted to have Frog Jones, a fresh new voice, join us.

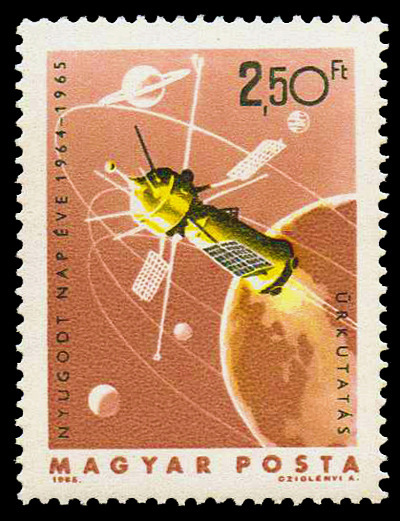

Stephan's Quintet, Hubble Space Telescope

Genres don't die. They just cycle back around. There were a couple of big surges for science fiction, and now we're in a lull, but sooner or later someone will write a great science fiction book, or make a great science fiction movie, and the fickle beast that is pop culture will swing its gaping maw back to the science fiction trough.

If you think about it, science fiction has part of the popular imagination ever since the Greeks told stories about strapping wings to your arms and flying around. True, Icarus is more of a cautionary tale of hubris, but from the perspective of a Greek we're still talking about the dangers of a potential technology, which is a common science fictional theme.

Science fiction is based on an imagining of future technology. The problem with such an imagination process is the degree of future you need to pull off. In 2012, the rate at which human knowledge increases is far faster than it was in the times of either Verne or even Asimov.

Nowadays, low-orbit space travel is routine, but no more impressive than flying an airplane in 1920. Not exactly the stuff of science fiction.

Faster than light speed? Possible.

Of course, if FTL is possible, then time travel?

Extraterrestrial life? Possible.

Those little pads on Star Trek that contain any book you'd ever want to read?

My point is, most of the normal science fiction tropes have begun to lose their "fiction." 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea just wouldn't feel like real science fiction if it had been written today. They're in a submarine. There's a giant squid. Big deal.

This, by the way, has happened before. That's why we see surges and lulls in science fiction; an incredible author with an amazing vision will come along and figure out what the world will look like in a hundred years, and then write about it. A swarm of copycats will follow.

The trick to renewing science fiction is to imagine beyond the current borders of science, then write about what life's gonna be like for the people who live then. That's getting harder and harder to do, because the borders of actual science are growing at such an incredible rate. That difficulty is compounded by the fact that this generation has seen a massive growth in technology, and it actually hasn't impacted the day-to-day life of a person noticeably. Sure, some things are easier, but the vast majority of the population still wakes up in the morning, goes to work, comes home, watches some television, and goes to bed. That tends to lead to disillusionment that technology can bring about a paradigm shift.

I have faith that this visionary exists, and eventually we'll see a book that is just a much a revelation now as the Foundation trilogy was for its release. Once that book breaks, a hundred copycats will follow, and science fiction will be back.

Right up until the scientists catch it up again. Thus will the cycle continue.

Frog Jones writes collaboratively with his wife, Esther. You can follow their blog here.

Stephan's Quintet, Hubble Space Telescope

Genres don't die. They just cycle back around. There were a couple of big surges for science fiction, and now we're in a lull, but sooner or later someone will write a great science fiction book, or make a great science fiction movie, and the fickle beast that is pop culture will swing its gaping maw back to the science fiction trough.

If you think about it, science fiction has part of the popular imagination ever since the Greeks told stories about strapping wings to your arms and flying around. True, Icarus is more of a cautionary tale of hubris, but from the perspective of a Greek we're still talking about the dangers of a potential technology, which is a common science fictional theme.

Science fiction is based on an imagining of future technology. The problem with such an imagination process is the degree of future you need to pull off. In 2012, the rate at which human knowledge increases is far faster than it was in the times of either Verne or even Asimov.

Nowadays, low-orbit space travel is routine, but no more impressive than flying an airplane in 1920. Not exactly the stuff of science fiction.

Faster than light speed? Possible.

Of course, if FTL is possible, then time travel?

Extraterrestrial life? Possible.

Those little pads on Star Trek that contain any book you'd ever want to read?

My point is, most of the normal science fiction tropes have begun to lose their "fiction." 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea just wouldn't feel like real science fiction if it had been written today. They're in a submarine. There's a giant squid. Big deal.

This, by the way, has happened before. That's why we see surges and lulls in science fiction; an incredible author with an amazing vision will come along and figure out what the world will look like in a hundred years, and then write about it. A swarm of copycats will follow.

The trick to renewing science fiction is to imagine beyond the current borders of science, then write about what life's gonna be like for the people who live then. That's getting harder and harder to do, because the borders of actual science are growing at such an incredible rate. That difficulty is compounded by the fact that this generation has seen a massive growth in technology, and it actually hasn't impacted the day-to-day life of a person noticeably. Sure, some things are easier, but the vast majority of the population still wakes up in the morning, goes to work, comes home, watches some television, and goes to bed. That tends to lead to disillusionment that technology can bring about a paradigm shift.

I have faith that this visionary exists, and eventually we'll see a book that is just a much a revelation now as the Foundation trilogy was for its release. Once that book breaks, a hundred copycats will follow, and science fiction will be back.

Right up until the scientists catch it up again. Thus will the cycle continue.

Frog Jones writes collaboratively with his wife, Esther. You can follow their blog here.

Published on March 31, 2012 01:00

March 29, 2012

The Feathered Edge: Culverelle Meets Jemina Puddleduck

A short while ago, I received this email from Sean McMullen, author of "Culverelle:"

Relating

to my story, I was re-watching Miss Potter (the movie on Beatrix

Potter's life) on the weekend, and many of the Lake District scenes were

shot at Derwent Water! So, Culverelle and Tordral meet Peter Rabbit and

Jemima Puddleduck. That would be quite a story.

I wrote back that he'd have to write it himself. And he did.

"Good morning, Sir Gerald."

"Good morning, Jemima. And what have you and the other ducks been doing lately?"

"Oh

bother the other ducks! I'm going on a date, it's so exciting. I met

this nice Mr Elf yesterday, and he invited me to dinner. He said to meet

him at dusk tonight, and to bring some things to help with the meal.

Now what did he say? Bring a baking dish, some parsley, some chives,

lots of breadcrumbs, olive oil, orange sauce – oh and an onion, bring a

nice onion."

"And where is dinner to be?"

"I don't know, but I'm meeting him at the old footbridge."

"Indeed!

Well, here's some advice for you. When you meet Mr Elf, someone behind

you just might call out 'Duck!' If that happens, don't turn around and

say 'Good evening', just flatten yourself on the path with your wings

over your head."

"Good heavens! Whatever for?"

"If you don't, you just might get an arrow through your poke bonnet."

… with apologies to Beatrix Potter.

Published on March 29, 2012 11:27

March 27, 2012

GUEST POST: Phyllis Irene Radford on Heroes, King Arthur, and Creating the "Merlin's Descendents" series

When I

read Malory's Le Morte

D'Arthur for the first time in junior high school, I knew I'd found

the heroes lacking in my life. I think that's

one of the reasons Arthuriana has lasted so long.

Everyone

has times when they need a hero. This first

reading of stories about King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table was long

enough ago that heroic figures were still supposed to be men, and I hadn't seen

enough of the world to realize that heroism can be a feminine characteristic as

well. More about that later.

At that time in my life, I knew I was smarter

than the football stars in school that my c

lassmate worshipped and lusted after. To me that made these heroes less than

lassmate worshipped and lusted after. To me that made these heroes less thanideal. I knew that my teachers were ordinary

people doing their job and going home to their families, like everyone else. I knew that my father had a bunch of military

medals, but he kept those in the safe and didn't talk about them. He was away from home serving his country so

much in my early years that I had trouble identifying him with heroes. Later I knew better.

I was hungry

for someone to look up to, someone who could solve the world's problems and still

have time to nurture the love of his life.

I still appreciated the great Romance in heroic stories.

King Arthur

and his Knights of the Round Table filled those requirements. I re-read Malory and then stretched my reading

into more modern renditions of the grand cycle of myth and legend—Mary Stewart

and Marion Zimmer Bradley topped my lists.

And in each re-telling of these favorite stories, I found new insight into

the character, the responsibility, and the duty of being a hero. Arthur and his cronies could be flawed, but they

still rose to the top of whatever challenged them.

Then I

saw the old Disney animated movie "The Sword in the Stone," based upon a book by

T.H. White. Arthur was still a hero, but

I fell in love with Merlin. Merlin saw what

needed doing so that Arthur could make things happen. Merlin was different, unique, special, and magical.

So, of

course I had to read The

Once and Future King by White.

I had the album of the musical Camelot,

derived from that volume. I saw that movie

too. Later in life I saw the stage play with

Robert Goulet as Arthur–he'd played Lancelot in the ORIGINAL Broadway play. I read everything fictional and non-fictional

about King Arthur and his knights. I dreamed

I had walked the archeological digs at Cadbury Hill, Stonehenge, Glastonbury Abbey,

and Hadrian's Wall.

Then

in 1971 I made my first trip to Britain.

There was no fence at Stonehenge and I was allowed to wander the entire

site alone, unfettered, imagination churning.

I knew I'd come home; a previous me had called this place home.

The ideas

spun and spun their golden web in my mind, enticing me into more research and even

more ideas. By this time I knew that women

were heroes too and their stories needed to be sung.

So, once

my writing career kicked into professional gear I made the conscious decision to

write my version of Arthur and Merlin and Lancelot, and Guinevere, and Morgan le

Fey, and… and… Merlin's daughter Wren. Another

trip to England helped me with on-site research. My husband took fabulous photos.

My degree

in history was in general history, I have no claim to expertise in any one area. I needed my stories—Merlin's story—to span multiple

generations and centuries. I needed to

send a hero, male or female, into many different historical crises, to nudge

events to make sure they happened the way we remember.

Deep in

my soul and buried in the research I discovered that Arthur and Merlin and all the

others came to represent a special code.

Honor, Truth, and Promises are meant to be kept; Justice, Peace, and Law,

must be defended.

Borrowing

from that long ago musical Camelot,

might doesn't make right. Might must be

used for right.

And so

in 1999, Guardian of the

Balance, Merlin's Descendants #1 saw print in hardcover from DAW Books. The first of 5 books beginning with Merlin's daughter

and running through the set up for the American Revolution. Now I have re-released the series of books, as

e-books at the Book View Café, and later at other distributors.

Guardian of the Vision,

Merlin's Descendants #3

debuts at the Book View Café this week, March 27, 2012. This is the most emotionally charged of the

five books, the hardest to write. I made my own spiritual journey following in

the footsteps of one man, with his wolfhound familiar of course, through the

maze of the religious wars during the early years of Queen Elizabeth I's reign.

I

found the hero I need in my literary life.

The job is still open in modern reality.

o0o

Phyllis

Irene Radford is a founding member of the Book View Café. Though raised in the seaports of America she

was born in Portland, Oregon and has lived in and around the city since her

junior year in high school. She thrives

in the damp and loves the tall trees.

For

more about her and her fiction please visit her bookshelf on BVC http://www.bookviewcafe.com/index.php/Phyllis-Irene-Radford/

Or her

personal web page http://www.ireneradford.com

Published on March 27, 2012 01:00

March 24, 2012

SPECIAL GUEST BLOG: Lambda Award Finalist J.M. Frey on creating "Triptych"

Today's Guest Blog is a special treat. J.M. Frey's impressive debut novel, Triptych, is a Finalist for the Lambda Award. It's an absorbing, moving, satisfying and humane story, one that marks Frey as an author to watch. Here she talks about her love affair with writing, and how she came to create such a compelling and original tale.

"A Fish Out Of Water"

I have an absolutely massive soft spot for

fish-out-of-water stories. I mean, huge. I blame, in the best way, J.M. Barrie

for this. (And yes, my professional name is my little tip-of-the-topper to Mr. Barrie

– thanks, Mom and Dad, for giving me the same initials.) I wanted, so badly, to

go to Neverland as a child.

This desire informed my reading and viewing

choices as a kid– if I the cover copy of a book even hinted at the possibility of someone from "our" world falling into

and experiencing another, then I was all over that. I must have watched Warriors of Virtue five billion times,

and I could probably still recite My

Little Pony's Escape From Catrina. Disney's Little Mermaid and Beauty and

the Beast? Yup. I really got turned onto fantasy with Piers Anthony's Xanth books, especially the Heaven Cent trilogy, and I know I read Howl's Moving Castle until the glue on

the spine flaked away (oh, how I wanted to be Howl!)

I love stories where the protagonists are

also "from" the world they are in, but are thrust into a situation that is new,

terrifying, and leaves them unstable. I loved Jennifer Robson's Chronicles of the Cheysuli. I love Naomi

Novak's Temeraire books now, and Anne

Rice's Lestat will always have a place in my heart for being a bit of a bumbler

in those first books, and I could die happy if I got cast as Constance Ledbelly

in Anne-Marie MacDonald's Good Night

Desdemona (Good Morning, Juliet).

Of course my tastes matured as I did, but

that one hook never quite got out of my skin. Tell me the film/comic/book has a

fish-out-of-water character and I will throw my wallet at it.

Which means, unsurprisingly, that when it

came to academic work, I focused on the ultimate fish-out-of-water: the Mary Sue. (Read more about this fanfiction

literary trope here.)

I became enamoured, and eventually went on to write my Master's thesis on the

topic. But before I did that, I wrote a lot of Mary Sue fanfiction – I wanted

to get the feel for the response it got online, the way people reacted to it,

and study the kind of feelings I had when I was writing and reading it.

One of the exercises I set myself was to

write an original Mary Sue. I

eventually did find a way to do it (and it will come out in June 2012 as The Dark Side of the Glass, from Double

Dragon Publishing), but my first attempt was a novella called (Back), and I failed. It wasn't a very

successful Mary Sue and was struck from my bibliography for my thesis. But the

story itself was well received when I sent it to my beta readers, so I went on

to sell it to a publisher.

I tell you all this so you know where I'm

coming from when I start to talk about the choices I made when I wrote Triptych.

Originally, (Back) was supposed to be a fish-out-of-water story about a Mother named

Evvie and Daughter named Gwen who meet each other, via a time travel McGuffin, when

they're both 26 years old. The conflict was supposed to arise from the fact

that Gwen had grown up to be a soldier, and a bit cold, and was dating Basil, a total geek-everyman that her mother

saw as a loser. Her mother wanted her to be stereotypically girly, fall for a

cowboy, be a nurse, raise some kids, all that stuff. The story was supposed to

be about gender performance and the way that different generations have

different milestones to define a "successful" life. And the first few drafts

were. It still is, in a way.

There was also mention of some aliens along

with my time travel MacGuffin, but mostly because I thought that the

time-travel technology can't have come from humanity, not if Gwen was meant to

have grown up in the 2020s; I didn't think we'd be advanced enough by then. I

needed some way for the technology to exist. It was a toss away line – something

about Gwen's alien coworker and teammate accidentally triggering the device.

That was my "oops" moment. Not so much

"Eureka!" as, "What's this mould growing on my specimens? Crap! Are they ruined

now?"

I owe a lot of what Triptych is to the beta reader on (Back), Liz Aitken. Like me, she had aspirations to be a writer at

the time, and also like me, she was working towards professional publication;

we were both teaching English in Japan and with some other local foreigners, we

had an ad hoc writer's circle that helped one another with our editing. (I've

since lost touch with Liz, and I wish I hadn't – Liz, if you're reading this,

email me! Did you get published? I hope so!)

Liz read (Back), but she also read between the lines. She handed me the

manuscript back and said, "Are Gwen and her boyfriend Basil sleeping with the

alien coworker?"

I spluttered. "What? What? No! Gwen and

Basil are not sleeping with… him,

her, it! I don't know! No!"

"Oh," she said. "Because right here, it

sure sounds like it."

She pointed to a paragraph, and I read it

through her eyes. "Damn," I said. "I… think they were sleeping with the alien.

I'll fix that. I'll--"

"Make it clearer," Liz said, at the same

time I blurted, "Take it out."

I blinked owlishly at her. "You want me to

leave it in?"

"Yeah. Think of how you can use that. I

mean, if Gwen's mother hates her now, just

wait until she realizes that her daughter is in a polygamous relationship with

an alien."

I knew next to nothing about polyamoury and

polygamy at the time, except for the dreadful things I kept hearing in the news

about the child-brides and wife-slaves rescued from religious compounds. I was understandably

wary. Absolutely nothing about the concept appealed to me.

Thank god for the internet, eh?

I spent a long time researching loving,

healthy poly-relationships and communities, talked to some poly folks, and

actually got quite into the concept myself. I learned that some of my friends were

poly, and I hadn't known. I read a bunch of webcomics and stories about it. The

more I researched, the more it appealed as a story line – and then, because I

am an academic at heart, I also started researching the social contracts and

mores of monogamy, homosexuality in other species besides humans, and family-groups

in animals. My eyes were opened and my mind blown! Hey, Earth was filled with poly relationships worth

celebrating!

(It came out after Triptych, but one of the best books on this topic I have ever read

is Sex at Dawn, by Christopher Ryan,

PhD and Cacilda Jethá, MD.)

Right, okay – so. I had decided to jump in

and make Gwen, Basil and the unnamed alien a family. And I needed to figure out

how to build the biology of my aliens.

A lot of discussion in the texts I read

talked about humans as binary creatures – symmetrical bodies, two sexes, two

genders, etc. Some of it was B.S. of course – human beings only have two sexes

and two genders? Ppffffft – but some of the biological stuff was solid. A

psychology report I read talked about why we anthropomorphise other creatures,

how we read each other's body language and facial expressions, basically, how

we communicate with our bodies. Humans trust things that are human-shaped. It's

a deep seated evolutionary thing-a-ma-bob, which is why a lot of "bad guy" aliens

in films are scary insectoid things, because that's as non-human-shaped as you

can get. I turned to the aliens of my childhood for reference – who did I

trust? And why? – and hit upon the Playmobil alien and astronaut set I had as a

kid. The Aliens and the Astronauts could hug.

So, two arms, two legs, forward facing eyes

– so, biologically, probably created offspring in a binary, too.

So I came to the conclusion that if it

wasn't biological, then I had to make the threesome aspect a social construct

rather than a biological one, much like our own two-some-ness is a social

construct. There needed to be a cultural precedent. I came up with a myth-cycle

for the aliens called The Deeds of Vren (sort of a mishmash of Odin's

wanderings, the life of Christ, and a lot of the Indian and Japanese myths

about where and how rules were handed down from the gods to humanity), and made

that the basis of the social rules of the alien's world.

Of course, none

of that made it into (Back)! The

story was way too short to allow for it, and had to remain focused on Gwen and

her relationship with her mother. But I was able to flesh out the backstory

better, give the alien more life. After the novella was published, I got a lot of feedback from readers about how

they wanted more of the unnamed alien, his culture, his relationship with Gwen

and Basil. I got a lot of emails saying, "What happens next?!"

I thought about

this, let it percolate, and then somehow one day I had decided that I was going

to write this as a novel. (Back)

became the first third of the book, and book eventually became known as Triptych (after several disastrous titles I won't share). But I

didn't know what to do with all the bits I had, all the research and the scenes

and the vague plot arcs. I wanted to do something domestic, something lovely

and sad about Gwen and Basil and the alien – his name was now Kalp – and their

relationship. I didn't want to do action or lasers or space opera. I wanted to

write about love, and what happens when people just don't understand or give

others the freedom to love where they'd like. That is, I wanted to write a love

story for people like I had been – people who only knew the bad stuff about

poly relationships, and none of the good. Only I didn't know where to start.

Liz to the rescue

again! She handed me two pages of writing one day and said, "I hope you don't

mind, but I was messing about and, um, I wrote this. As an exercise. To see if

I could, you know."

It was amazing.

It was brilliant. It was Kalp, poor distraught Kalp, on his way to meet his new

team on Earth for the first time, being utterly fish-out-of-water. I was, of course, hooked. Liz's voice is very

different from mine on the page, so when I read what she'd done I couldn't

believe how alien Kalp sounded to me.

It was perfect.

"Can I have

this?" I blurted. "I mean, can I use this? Can I write Kalp like this, is it

okay?"

Liz gave me

permission to subsume those two pages into the novel, and Kalp's voice and

personality were born. Very little of that original writing remains in Triptych. It has been edited away, the

tenses changed and the sentences scrambled, but the kernel of it remains in

Kalp.

Now that I knew

what Kalp sounded like, I was able to flex my wings, get into the nitty gritty

of the world building, of the mythology and social hierarchy of Kalp's people.

There are , god, hundreds of pages worth of stuff

that's not in the book – art and culture, sports and architecture, so much I wanted

to write about in the story, but had to leave out because the story was about

Kalp's culture shock and his desperate need for comfort, not a text book about

the history of his society.

I had to make a

lot of tough choices, too. I had to choose -

was I writing a story or a manifesto? I had to temper a lot of my innate

essay-writing drive, had to get off my soapbox and remember that I was telling

a story, not giving a lecture. As a result, there are some aspects that are

weaker on than others – I wish Kalp wasn't quite so male, and I wish that I'd had a chance to talk up the problematics

of his own society a bit more, but then I had to remember that Kalp is just

desperate to fit in, so he would act as male as possible, and he would

nostalgia-wash his own life up until then, he would desperately cling to the

good on Earth and try to ignore the bad. For example, a local Earth farmer has

tried to go produce from his world – Kalp notes that some of it was an utter

failure, tough and wrinkled and colourless, but chooses to latch onto the fruit

and veg that flourished on Earth. That's just his personality.

I didn't want to

assign a gendered pronoun to Kalp at first, but a beta reader pointed out that

it was fatiguing to read Kalp's name all the time, so I had to sacrifice that

to the story. At least I got to turn it into a bit of a plot point!

So, that's how I built Kalp and his world,

and created the kind of fish-out-of-water story that I hope will inspire the

next generation of writers, the way that the others inspired me. Gwen is out of

time, Kalp is lost in the wrong culture, and Basil is a geek among jocks; and

yet, somehow, for just a brief moment, they find one another and everything is

perfect, and they are exactly where they should be.

Where to buy?

Kindle edition at $2.99 here.

Trade paperback at Amazon.com here

If you'd rather buy from a real bookstore, try Powell's here

Or order it from your friendly nearby bookstore; here's the ISBN: 978-1897492130

Published on March 24, 2012 01:00

March 22, 2012

The Feathered Edge: Return to Meviel...With Pirates!

One of the challenges of writing short fiction is how much must be accomplished in how few words. Harry Turtledove once said that novels teach us what to put in a story, but short stories teach us what to take out. Every story element must serve multiple purposes - setting the scene and evoking the larger world beyond it, creating and heightening tension, revealing character -- oh, and moving the plot along. It's a tall order to accomplish in only a few thousand words. Some writers do the world-building part so well in even so short a space that it keeps beckoning them to return. That happened to me with a series of short stories I wrote for Sword and Sorceress (that eventually became a fantasy trilogy, The Seven-Petaled Shield). It also happened to Madeleine E. Robins with her world of "Meviel."

The first I saw of this wonderful place was the story Madeleine wrote for the first anthology I edited, Lace and Blade from Norilana Books. It was called "Virtue and the Archangel" and began thus:

Veillaune meCorse left her virtue in the tumbled sheets of a chamber at the Bronze Manticore. This act, which would have licensed her parents to cut her off from family and fortune, was a grave error; but with her maidenhead, Veilliaune also left the Archangel behind, and that was a calamity.

I guess the world of Meviel was just too enticing for one such tale to suffice, and when I was reading for the next volume, Madeleine queried me whether a second story in the same setting would be of interest. Bring it on, I said, and received the hilarious "Writ of Exception." I'm not going to divulge any of its secrets; you'll have to read it for yourself.

Time passed, as it does, but the years did not dim Meviel's luster, because when I inquired of Madeleine if she would like to do a story for the anthology that would become The Feathered Edge: Tales of Magic, Love, and Daring, she wrote:

I'm working on a Meviel story... No alternate sexuality per se (after the last two stories I sort of wanted to change things up a bit) and no romance particularly: just a girl who reads too much and gets kidnapped by pirates and...

I ask you, what editor could resist that premise? Who knew there were pirates in same world as Veillaune meCorse and the Archangel? True to form, the pirates in "Wreath of Luck" are and are not your usual sort. There's a lovely twist of -- is it magic or superstition or a plucky young heroine creating her own good fortune?

If you love Madeleine's work as much as I do, you'll want to check out her wonderful Regency novels on Book View Café (and the latest "Sarah Tolerance" adventure, The Sleeping Partner, in paper, too). Madeleine's also got a story in Beyond Grimm: Tales Newly Twisted.

Published on March 22, 2012 01:00

March 20, 2012

The State of Science Fiction, A Personal View

Exploding Planet, by Mico Niemi

I just finished reading Jo Walton's marvelous book, Among Others, and was delighted at the many references to science fiction in 1979/1980, when the story takes place. At that time, I was an avid reader of sf like the protagonist, and I well remembered the excitement of discovering new authors, new books, the exhilaration of new ideas and the idealist belief that through science and technology, we could build a better world (not to mention explore strange new ones and seek out new civilizations).

Walton's book made me want to run to my shelves and re-read all my old favorites. Then I wondered what had happened to the love affair with sf. Did we all grow up and give up, or did we get lost in Mirkwood and never come out? Is today's sf too technological for new readers? Has the sense of wonder disappeared? Or merely gone sideways, so that instead of tuning into Star Trek confident future, we are wallowing in angsty vampires?

In the past, the genre of science fiction received two enormous cultural boosts to its popularity. The first came at the end of the 19th Century, with the Victorian love-affair with invention and scientific discovery. This was the era that gave us Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, Conan Doyle's The Lost World, and inspired spawned the next generations of writers. It also continues to generate tales of mechanical gee-whiz, romance, and adventure through the current steampunk genre, which hearkens back to a time when technological marvels -- steam engines and the like -- were understandable by the ordinary person. The era had its version of the Renaissance man (or woman) - someone knowledgeable and skillful in many fields, often a person who pursues knowledge for its own sake. This sort of education presupposed a certain amount of leisure time and financial stability, which meant the characters were free to take off on adventures because they didn't need to earn their bread. (Few complained that the poor were largely excluded, except as secondary characters.)

In the past, the genre of science fiction received two enormous cultural boosts to its popularity. The first came at the end of the 19th Century, with the Victorian love-affair with invention and scientific discovery. This was the era that gave us Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, Conan Doyle's The Lost World, and inspired spawned the next generations of writers. It also continues to generate tales of mechanical gee-whiz, romance, and adventure through the current steampunk genre, which hearkens back to a time when technological marvels -- steam engines and the like -- were understandable by the ordinary person. The era had its version of the Renaissance man (or woman) - someone knowledgeable and skillful in many fields, often a person who pursues knowledge for its own sake. This sort of education presupposed a certain amount of leisure time and financial stability, which meant the characters were free to take off on adventures because they didn't need to earn their bread. (Few complained that the poor were largely excluded, except as secondary characters.)The second boost came with the space race of the mid-20th Century and the focus on science education, plus the coupling of astronomy, post-World War II pyrotechnics, and old-fashioned derring-do. Physics, chemistry and mathematics became glamorous, or at least more glamorous than they had been before and were since. Biology and social sciences took second seat to the disciplines everyone said we needed to beat the Soviets to the Moon. As an interesting side note, this emphasis on hard science and individual ruggedness created a resistance to the use of psychology in understanding the personal and group challenges of space flight, a trend that has now fortunately been remedied.

Then came a period of disenchantment with technology and with hard science itself. It seemed that technology created more problems than it solved, and the future no longer looked so shiny. Average people could no longer understand everyday devices -- remember the jokes about how many PhDs it takes to program a VCR? People longed for times and places where both problems and solutions were simpler. Frodo might have had to struggle mightily to haul the Ring up the slopes of Mt. Doom, but he didn't have to worry about AIDS, global warming, or the newest IRS regulations.

Not so long ago, there was lots of "science fantasy," of fantastical space tales and blurring of today's marketing distinctions. (Consider, for example, the Darkover and Pern series, both of which began as science fiction but are now shelved with fantasy.) It seemed to me that the genres divided, that once people read both, and now they tended to read one or the other, and more of them read fantasy. Certainly, this separation is reflected in the diminishing sales figures for science fiction.

Is sf dying? Has it become commercially unfeasible to publish?

As to the unprofitability of science fiction in a traditional format, I sadly fear this has become the case, at least for new and midlist authors. Notable exceptions include media tie-ins, books by Big Names, and steampunk. My own suspicion is that this does not represent a true disaffection with speculative fiction, but rather having to split that pie into too many pieces.

I believe there are plenty of readers who love science fiction exclusively, and even more (like myself) who read widely across genre lines. Such readers may not equal those who create New York Times Bestseller lists, but they are numerous enough to support the field. Until recently, the challenge has been to connect such readers with great new science fiction. Bookstores, particularly those catering only to high-volume best-sellers, made it more difficult to find such books. As major traditional publishers devoted less space on their lists to science fiction, those authors have migrated to smaller presses, which are less likely to be carried by chain book stores.

Recently, on an online forum, an otherwise well-educated reader asked if there was any good science fiction currently being published. I was able to write back with a couple of dozen authors, some of whom have been around for quite some time, others a middling time, but very few very recently debuted excellent hard sf writers.

I propose that the internet can be the salvation of science fiction as a genre, allowing (tech-fluent) readers to discover and discuss both new and classic works. At least, I hope so.

Try out my own contributions to novel-length sf, Jaydium and Northlight. Read sample chapters here and here.

Try out my own contributions to novel-length sf, Jaydium and Northlight. Read sample chapters here and here.

Published on March 20, 2012 01:00

March 17, 2012

GUEST POST: Brenda Clough on Arctic Centennial

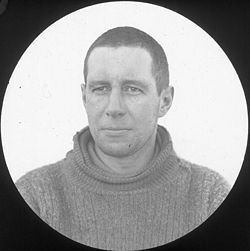

March 16 or 17, 2012, is the 100 year anniversary of the death of Antarctic explorer Lawrence Edward Grace 'Titus' Oates. He's the quintessential British hero, a role model for the kiddies and a mine of inspiration for writers, including me. He died possibly one of the most dramatic deaths of all time; when you want an example of character being destiny Oates is a perfect case to cite.

Also along about now is the centennial of the death of Robert Scott

and his party of explorers, of which Oates was a member. The actual

date of their demise is understandably fuzzy, since they froze and

starved to death in a dark tent on the ice. Uncounted heroes have died

unknown and unsung, but what saved Scott from oblivion was his writing.

He wrote, right until the bitter end, and his last journal entries have a terrible power and drama. Notes to his sponsors, letters to his wife,

and, most importantly, his Letter to the Public, which included a plea

for support for the widows and orphans the expedition would leave. This

plea was powerful enough to not only pension those widows and orphans,

but fund the Scott Polar Research Institute

at Cambridge. He was a sufficiently great writer to be able to reach

his readership right from his deathbed. Not only did he maintain

heroism and courage right to the end, but he told us about it. Amazing!

And like all known writers, Scott was lucky. His frozen body (and

those of his companions) lay with all his letters, papers and equipment

out on the ice for the entire brutal 6-month Polar winter. In the

spring, when the sun came back, the other members of his expedition went

out to look for him. Finding their little tent — it was nearly buried

in blizzard drift — must have been like stumbling across one selected

pebble on a beach. That lucky discovery is the only reason we have

Scott's notes, and the only way their fate is known. The rescue party

took the journal from under Scott's pillow. Oates' body was never found,

and the only record of his death is what Scott noted

in his journal. Slide down on that last link to March 16-17 and read

the eyewitness account. You have to hold your breath, while you read

it.

This year boatloads of commemorative events — museum exhibits, an expedition –

are scheduled to take place. But I think I must remember these

Edwardian explorers in a way they would have approved — by writing.

Deborah adds: Speaking of writing, you can check out Brenda's newest novel, newest novel Speak to Our Desires is out exclusively from Book View Café. She also has stories in Book View Café's two steampunk anthologies, The Shadow Conspiracy and The Shadow Conspiracy II, as well as in BVC's many other anthologies including our latest, Beyond Grimm (co-edited by Deborah and Phyllis Irene Radford!)

Published on March 17, 2012 09:16