Deborah J. Ross's Blog, page 154

November 29, 2011

Thanks, Anne McCaffrey, and Genre Boundaries

Reposted from Book View Cafe blog:

Anne McCaffrey's death, and all the reminiscences and tributes

Anne McCaffrey's death, and all the reminiscences and tributes

offered in her memory, intersected with what-I-am-thankful-for. Many

people, writers and readers both, have described the ways they are

thankful for her work and her personal presence in their lives. They've

said it far better than I, but each memory is personal and hence,

unique. Writer Juliette Wade blogged on how McCaffrey's "Pern" set an example for her own work by blurring the borderlines between fantasy and science fiction.

One of the things about McCaffrey's work that left a deep impression on me was not so much the "blurring"

of genre lines as how she combined story elements in interesting ways.

More than that, when I read everything of McCaffrey's I could get my

hands on, I was astonished at how many genres she wrote in. I saw her

telling stories in whatever form they needed to take; I saw that she,

like me, was interested in a lot of different things and she was

fearless in pursuing them.

Certainly,

Certainly,

it's become much more difficult for anyone but a Big Name Writer to

switch around from fantasy to science fiction to something in between to

romance/women's fiction, and so forth. The bean-counters and marketing

departments hold the purse strings. Many of us have found, to our

sorrow, that such limitations are not lightly flaunted. "Marketing says

they can't place this," is too often a death knell.

Even

Even

while we wrestle with the practicalities of trying to earn a living by

writing, we should not — we must not — allow such forces to hedge in our

imaginations. About the time I sold my first novel, I remember people

talking about how important that debut was because it was the book you'd

be re-writing for the rest of your career. I was appalled, for much as I

loved the story, the characters, the world of Jaydium, there

were many other stories, characters and worlds screaming at me —

pleading with me, haunting my dreams — to write them. That's one of the

glories of short fiction, which allows me to play in diverse and alien

sandboxes, with no computers tracking my sales figures to determine if

my next novel will be marketable.

I don't expect I will ever get to the point where a publisher will

I don't expect I will ever get to the point where a publisher will

gladly bring out my next book, regardless of genre. But I never, ever

want to stop dreaming in more than one color!

Thanks, Anne, for this and much more.

Anne McCaffrey's death, and all the reminiscences and tributes

Anne McCaffrey's death, and all the reminiscences and tributes offered in her memory, intersected with what-I-am-thankful-for. Many

people, writers and readers both, have described the ways they are

thankful for her work and her personal presence in their lives. They've

said it far better than I, but each memory is personal and hence,

unique. Writer Juliette Wade blogged on how McCaffrey's "Pern" set an example for her own work by blurring the borderlines between fantasy and science fiction.

One of the things about McCaffrey's work that left a deep impression on me was not so much the "blurring"

of genre lines as how she combined story elements in interesting ways.

More than that, when I read everything of McCaffrey's I could get my

hands on, I was astonished at how many genres she wrote in. I saw her

telling stories in whatever form they needed to take; I saw that she,

like me, was interested in a lot of different things and she was

fearless in pursuing them.

Certainly,

Certainly,it's become much more difficult for anyone but a Big Name Writer to

switch around from fantasy to science fiction to something in between to

romance/women's fiction, and so forth. The bean-counters and marketing

departments hold the purse strings. Many of us have found, to our

sorrow, that such limitations are not lightly flaunted. "Marketing says

they can't place this," is too often a death knell.

Even

Evenwhile we wrestle with the practicalities of trying to earn a living by

writing, we should not — we must not — allow such forces to hedge in our

imaginations. About the time I sold my first novel, I remember people

talking about how important that debut was because it was the book you'd

be re-writing for the rest of your career. I was appalled, for much as I

loved the story, the characters, the world of Jaydium, there

were many other stories, characters and worlds screaming at me —

pleading with me, haunting my dreams — to write them. That's one of the

glories of short fiction, which allows me to play in diverse and alien

sandboxes, with no computers tracking my sales figures to determine if

my next novel will be marketable.

I don't expect I will ever get to the point where a publisher will

I don't expect I will ever get to the point where a publisher will gladly bring out my next book, regardless of genre. But I never, ever

want to stop dreaming in more than one color!

Thanks, Anne, for this and much more.

Published on November 29, 2011 12:25

Award Nominations Are A Wonderful Start to the Day

Hastur Lord was nominated for the 2011 Gaylactic Spectrum Award! It didn't win, but it's in some very fine company. Since the core of the novel was a partial manuscript Marion wrote during the final year of her life, and since it continued the characters and relationships she'd established in The Heritage of Hastur, focusing on a heroic and sympathetic gay protagonist, one that appeals to a wide range of readers, I am especially pleased. I think Marion would have been, too.

Published on November 29, 2011 08:43

November 24, 2011

Gossip and Community

The internet is practically an engraved invitation to indulge in gossip and rumor. It's so easy to blurt out whatever thoughts come to mind. Once posted, these thoughts take on the authority of print (particularly if they appear in some book-typeface-like font). Have you ever noticed how much easier it is to question something when it appears in Courier than when it's in Times New Roman? For the poster of the thoughts comes the thrill of instant publication. Only in the aftermath, when untold number have read our blurtings and others have linked to them, not to mention all the comments and comments-on-comments, do we draw back and realize that we may not have acted with either wisdom or kindness.

To make matters worse, we participate in conversations solely in print, without the vocal qualities and body language that give emotional context to the statements. I know a number of people who are generous and sensitive in person, but come off as abrasive and mean-spirited on the 'net. I think the very ease of posting calls for a heightened degree of consideration of our words because misunderstanding is so easy.

I've been speaking of well-meaning statements that inadvertently communicate something other than what the creator intended. I've been guilty of my share of these, even in conversations with people with whom I have no difficulty communicating in person. What has this to do with gossip?

Where this is leading is that such statements can be hurtful and damaging whether they are true or not. They are particularly embarrassing to the tellers when they are false and that falsehood is revealed. Human beings are peculiar creatures. When we have injured someone by passing on a rumor, false or not, instead of doing what we can to ameliorate the situation, we set about defending ourselves. "But it was true!" is one tactic, or "I didn't know!" or "Blame the person who told this to me!" Or we find some way to shift responsibility to the person who is the subject of the gossip. Even well-meaning people, people who see themselves as honest and kind, people who should have known better than to spread rumors, do this.

I believe that when we engage in gossip or rumor, we damage not only the person we have spoken ill of, but the bonds of trust in our community. We divide ourselves into those who are safe confidantes and those who are tattlers, between those who are willing to give us the benefit of the doubt and those who will use any excuse to criticize and condemn us.

A huge piece of the problem, in my experience, is that we are inundated with role models of gossipers. We are told overtly and covertly that it is not only acceptable but enjoyable to speak ill of others and to relish their misfortune. If they have no discernible misfortune to begin with, well then we will create some! If media portray the pain of those who are gossiped about, it is often to glorify retaliation in kind. Almost never are we taught what to do when we speak badly. Saying "I'm sorry," or "Shake hands and make up," (as we're forced to do as small children) does not make amends.

Certainly, we must begin by looking fearlessly at what we have done or said (or left undone and unsaid), but we must also be willing to accept that there is no justification for our behavior. It doesn't matter if what we said was true or not if it harmed someone. It doesn't matter if we were hurting or grieving or too Hungry-Angry-Lonely-Tired.

What we have done does not make us unworthy, unlovable, inadequate, or anything except wrong. Good people can be wrong. Good people, when wrong, strive to make things right.

When we do this, we strengthen not only our relationships and our communities, but our own ability to choose better next time. As we have compassion for others, we owe ourselves compassion -- not excuses, not defenders, not "who's on my side," but gentle understanding, encouragement, patience, and courage.

Photo by Rebecca Kennison, Gossips in the Altstadt in Sindelfingen, Germany, licensed under Creative Commons.

Published on November 24, 2011 01:00

November 23, 2011

Howard Jones on The Roots of Arabian Fantasy (on SF Signal)

Awhile back, I wrote about my experience moderating a panel on "Islamic fantasy" at World Fantasy Convention. On of the panelists was Howard Andrew Jones, whom I had not met before but whose name I recognized from the small amount of research I was able to do in preparation. Howard was a delight (actually, all the panelists were wonderful, but in different ways) and his knowledge of Middle Eastern folklore and the traditions of written literature of the Muslim world were a wonderful resource for the panel. I especially enjoyed how he would offer some bit of fascinating scholarly background and then apologize, with genuine modesty, for going on in such detail -- when the rest of us were going, More! More! I wished I could have taped or transcribed the whole thing to share with you.

Now Howard's article on Arabian fantasy is up on SF Signal here: so you can get a taste of the discussion, and an eensy bit of the benefit of his knowledge. Here's an excerpt:

[The] version of the 1001 Nights we have today is not the

same as the version from the 10th century, or the 15th century. More and

more layers were added by succeeding storytellers. A few generations

after the 8th century when they lived, Haroun al-Rashid and his best

friend and vizier, Jafar, were dropped into the story mix, sometimes

adventuring in Baghdad in disguise at night. In later centuries,

characters and place names from Muslim Egypt were added. When Antoine

Galland assembled his collection of Arabian Nights in the 1700s and launched a sensation, he used some stories that he claimed came from a Syrian Christian. They're probably

of Middle-Eastern origin, but perhaps it shouldn't really matter. (I'm

not really troubled by this sort of "cultural appropriation" because it

strikes me as essentially good natured. I liken it to someone excitedly

joining a game that is already under way. Should that person be excluded

because they lack the appropriate ethnicity? Should the Indians have

excluded the Persians, and then the Persians the Arabs, from joining in

the fun? Why then should we dismiss Antoine Galland because he is an

18th century Frenchman, even if he invented rather than found Ali Baba

and Aladdin? All of the tales were created by someone, some time, and

Galland's "discoveries" are pretty nifty.)

Doesn't that make you want to click over to SF Signal and read the whole thing? And then rush out and get Howard's books? It does to me!

Now Howard's article on Arabian fantasy is up on SF Signal here: so you can get a taste of the discussion, and an eensy bit of the benefit of his knowledge. Here's an excerpt:

[The] version of the 1001 Nights we have today is not the

same as the version from the 10th century, or the 15th century. More and

more layers were added by succeeding storytellers. A few generations

after the 8th century when they lived, Haroun al-Rashid and his best

friend and vizier, Jafar, were dropped into the story mix, sometimes

adventuring in Baghdad in disguise at night. In later centuries,

characters and place names from Muslim Egypt were added. When Antoine

Galland assembled his collection of Arabian Nights in the 1700s and launched a sensation, he used some stories that he claimed came from a Syrian Christian. They're probably

of Middle-Eastern origin, but perhaps it shouldn't really matter. (I'm

not really troubled by this sort of "cultural appropriation" because it

strikes me as essentially good natured. I liken it to someone excitedly

joining a game that is already under way. Should that person be excluded

because they lack the appropriate ethnicity? Should the Indians have

excluded the Persians, and then the Persians the Arabs, from joining in

the fun? Why then should we dismiss Antoine Galland because he is an

18th century Frenchman, even if he invented rather than found Ali Baba

and Aladdin? All of the tales were created by someone, some time, and

Galland's "discoveries" are pretty nifty.)

Doesn't that make you want to click over to SF Signal and read the whole thing? And then rush out and get Howard's books? It does to me!

Published on November 23, 2011 11:26

November 21, 2011

On Naive Prose

Photo by Pauline Eccles

"What did you think of (self-published first novel)?" I asked my husband, fellow writer Dave Trowbridge.

He paused for a moment. "The ideas were interesting, and the sentences grammatically correct..."

I waited, since he was so clearly trying to identify what bothered him. Finally, he added, "but the prose was naive."

Now that's a description you don't often hear. I'd read the first few pages out of curiosity after I was on a panel with the author. My initial reaction had been that I understood why the book hadn't sold to a traditional publisher. I wouldn't say the prose was awful or unintelligent, only that it didn't feel professional. And yet even in those few pages, I was able to discern enough of a "hook" to suggest an actual story. You know the phrase, "You can't get there from here"? This was a case of, "You can't get there by this method."

Naive prose, as much as I understand the nebulous concept, is not just overwritten or heavy-handed, although it might be. It's badly timed.

Certainly, we are going to lose readers by overwhelming them with details at the beginning, new words, a host of strange characters, alien settings, supernatural world-building, romantic tension, backstory, etc., all at once. We want to carefully select what we put into those opening scenes, enough to evoke the setting, generate interest in the character and her problem (or some other way of connecting with the reader). We can also foreshadow what will be important later.

It's crucial that we not give the reader too little or too much... and that we introduce all those vital pieces of information at the right time. What's the right time? Not right before or -- even worse -- right after the critical incident for which we needed that information. Not all glumped together so the reader can't tell what's important and what's not, and can't absorb or integrate all that material at one time anyway. Not in random order. I think all these are earmarks of naive prose.

We want our readers to feel secure and competent -- trusting that they have everything they need to follow along with the flow of the story (or, even more fun, anticipating how characters will react or what simmering problems will become active or who done it -- even if the readers' expectations don't come true, it's fun to have that sense of active reading). They should feel that we've played fair with them -- no rabbits out of hats in a world that has neither rabbits nor hats! -- and that they have been able to notice effortlessly everything of importance.

After the first few toe holds of orientation, we can fill in, flesh out, make connections, foreshadow, build tension, set the stage. Even if what comes next is unexpected, it need not and should not be wholely out of possibility for what we've established for the world and its characters. But the reader should not have to agonize over every detail, trying to figure out where it fits and if it will matter later.

Naive prose may not necessarily convey too many details or the wrong ones, but presents them in the wrong order and at the wrong time and in the wrong tempo. That's something to think about.

Published on November 21, 2011 12:08

November 16, 2011

Percolation and Writing Goals, thanks to Linda Nagata

Linda Nagata (who incidentally is a terrific writer, and you can find her work in ebook form at Book View Cafe) offers some thoughts on writing goals versus "Percolation" here.

The problem with the word-count-per-day goal — that is, swearing to

oneself to write a thousand or two-thousand words everyday — is that to

be successful you have to have a pretty good idea of what happens next

in your story.

....

It's pretty clear that, for me at least, ideas need to percolate. I wish

it weren't so. I wish I could sit down and know what comes next, and

write it, and then move on to another project. I wish I didn't squander

so much time that could be put to productive use doing other things. But

it is what it is, and I've been dealing with the process long enough

that, despite the frustrations, I can remain fairly confident that the

words will eventually come.

I suspect that even those of us who are not participating in NaNoWriMo are thinking about the process of "just writing."

Here's my response: We think very much alike on this. It's so easy to fall into quantifying creative output -- so many words per day, so many pages per week. Goals are good, but creating a story involves so much more than those final words.

I'm a revision-based writer, so I do push myself to draft quickly when the story is flowing. But I'm experienced enough to realize when it isn't, when it's time to step back, go off and do something else, and get my mind derailed from the oncoming train wreck. If the bones of the story are sound, even if they aren't all there, I have what I need to work with.

I wonder if this is why NaNoWriMo doesn't appeal to me, but I've done well with shorter length/time challenges. Novels are too complex to barrel through in a month.

The problem with the word-count-per-day goal — that is, swearing to

oneself to write a thousand or two-thousand words everyday — is that to

be successful you have to have a pretty good idea of what happens next

in your story.

....

It's pretty clear that, for me at least, ideas need to percolate. I wish

it weren't so. I wish I could sit down and know what comes next, and

write it, and then move on to another project. I wish I didn't squander

so much time that could be put to productive use doing other things. But

it is what it is, and I've been dealing with the process long enough

that, despite the frustrations, I can remain fairly confident that the

words will eventually come.

I suspect that even those of us who are not participating in NaNoWriMo are thinking about the process of "just writing."

Here's my response: We think very much alike on this. It's so easy to fall into quantifying creative output -- so many words per day, so many pages per week. Goals are good, but creating a story involves so much more than those final words.

I'm a revision-based writer, so I do push myself to draft quickly when the story is flowing. But I'm experienced enough to realize when it isn't, when it's time to step back, go off and do something else, and get my mind derailed from the oncoming train wreck. If the bones of the story are sound, even if they aren't all there, I have what I need to work with.

I wonder if this is why NaNoWriMo doesn't appeal to me, but I've done well with shorter length/time challenges. Novels are too complex to barrel through in a month.

Published on November 16, 2011 16:51

November 15, 2011

Sailing the Seas With Horatio

Today's blog, on reading the C. S. Forester "Hornblower" books (after watching the A & E series with Ioan Gruffudd) appears on Book View Cafe. Here's the beginning...

I've

I've

been reading the C. S. Forester "Horatio Hornblower" novels, one after

the other. It's really my husband's fault. He's usually extraordinarily

recalcitrant about watching movies, whether at home or in a theater. One

Friday night, he indicated his willingness to consider it, so we looked

over the DVD collection and embarked upon the A & E "Hornblower"

series at the sedate pace of one-episode-per-week. (Of course, we did

not stop there, but proceeded to Master and Commander and the

1951 Hornblower movie with Gregory Peck and Virginia Mayo.) For those

who have not had the pleasure of reading these stories, Horatio

Hornblower is a fictional naval officer during the Napoleonic Wars.

Actual events and personages are woven into the tales, although Forester

takes care that the exploits of his hero do not alter history.

As visually appealing as the films are, we immediately reached for

the books. I'd read a few of them many years ago, but never had the

experience of moving from one adventure to the next, watching the

maturation not only of the titular character but of the author.

C. S. Forester must have been quite a character. After writing

propaganda for Britain during WW II, he came to Hollywood to write the

script for a pirate film. Before he could finish it, the Errol Flynn

movie Captain Blood came out, effectively stealing the thunder

from Forester's project. To make matters worse, Forester was facing an

impending paternity suit (I am not making this up — it's from

the biographical notes at the end of the Back Bay Press editions), so he

"jumped aboard a freighter bound for England." He spend the voyage

outlining the first of the Hornblower novels, Beat to Quarters (The Happy Return), which was published in 1937.

.... for more, click on over to the Book View Cafe blog...

I've

I'vebeen reading the C. S. Forester "Horatio Hornblower" novels, one after

the other. It's really my husband's fault. He's usually extraordinarily

recalcitrant about watching movies, whether at home or in a theater. One

Friday night, he indicated his willingness to consider it, so we looked

over the DVD collection and embarked upon the A & E "Hornblower"

series at the sedate pace of one-episode-per-week. (Of course, we did

not stop there, but proceeded to Master and Commander and the

1951 Hornblower movie with Gregory Peck and Virginia Mayo.) For those

who have not had the pleasure of reading these stories, Horatio

Hornblower is a fictional naval officer during the Napoleonic Wars.

Actual events and personages are woven into the tales, although Forester

takes care that the exploits of his hero do not alter history.

As visually appealing as the films are, we immediately reached for

the books. I'd read a few of them many years ago, but never had the

experience of moving from one adventure to the next, watching the

maturation not only of the titular character but of the author.

C. S. Forester must have been quite a character. After writing

propaganda for Britain during WW II, he came to Hollywood to write the

script for a pirate film. Before he could finish it, the Errol Flynn

movie Captain Blood came out, effectively stealing the thunder

from Forester's project. To make matters worse, Forester was facing an

impending paternity suit (I am not making this up — it's from

the biographical notes at the end of the Back Bay Press editions), so he

"jumped aboard a freighter bound for England." He spend the voyage

outlining the first of the Hornblower novels, Beat to Quarters (The Happy Return), which was published in 1937.

.... for more, click on over to the Book View Cafe blog...

Published on November 15, 2011 10:52

November 11, 2011

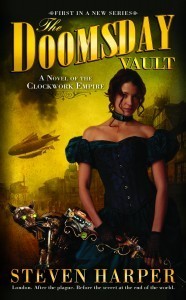

GUEST BLOG: Steve Harper on Writing Steampunk

THE SPEED OF STEAM, by Steve Harper

A couple weeks ago on a Friday afternoon, a file landed in my email.

Big one. It was the copyedited manuscript for THE IMPOSSIBLE CUBE, the

sequel to THE DOOMSDAY VAULT (which is now on sale and has mad

scientists and zombies in it). Could I go through the manuscript and

pop it back within ten days?

Whoa.

A number of writing blogs have already commented on the speed of writing

these days, how just a few years ago, I would have received a big pile

of paper in the mail with red marks all over it, and after I went though

it, I would have had to make a trip to the post office. Now I read and

upload a file, yada yada yada.

I just want to add that it feels wrong. For steampunk, I mean.

See, I think part of steampunk's appeal is the way it slows us down.

Steampunk puts us in a world before telephones and jet planes. When

communicating with someone on the other side of town meant dashing off a

postcard. When newspapers lived by the telegraph wire. When

international travelers went by train or ship or even dirigible, and

going around the world took eighty days instead of eighty hours. When a

new advancement in processing speed meant the Royal Mail had worked out

a more efficient sorting system. Our world goes so fast, it's nice to

take a break in a place in which everything goes a little slower.

As a result, it feels like all steampunk should be written at a rolltop

desk on a big, clunky typewriter with a sticky H and a crooked M while a

Victrola plays scratchy music in the background. Manuscripts should be

bundled into boxes tied with brown string. Letters to one's editor

should be scribbled with a fountain pen and dropped into the afternoon

post.

And yet, I flip words into a 2-terrabyte computer with dual-core

processor hooked up to the Internet via high-speed DSL cable modem while

four speakers croon a mix by Danny Elfman, and I toss letters to my

editor into the aether of the Internet It makes me feel out of sorts

and wrong.

Not wrong enough to make write the long way, mind. Anachronism does

have its limits.

But I'm a writer with a good imagination. So when I write steampunk, in

my head my computer becomes a typewriter and my contact lenses become

spectacles. My sweatshirt becomes a tweed jacket and my study with

central heat becomes a drafty garret. My dog and my pot of tea become .

. .

Well. I suppose not everything has to change.

Steven Harper usually lives at http://www.theclockworkempire.com . His

steampunk novel THE DOOMSDAY VAULT, first in the Clockwork Empire

series, hits the stores in print and electronic format November 1.

A couple weeks ago on a Friday afternoon, a file landed in my email.

Big one. It was the copyedited manuscript for THE IMPOSSIBLE CUBE, the

sequel to THE DOOMSDAY VAULT (which is now on sale and has mad

scientists and zombies in it). Could I go through the manuscript and

pop it back within ten days?

Whoa.

A number of writing blogs have already commented on the speed of writing

these days, how just a few years ago, I would have received a big pile

of paper in the mail with red marks all over it, and after I went though

it, I would have had to make a trip to the post office. Now I read and

upload a file, yada yada yada.

I just want to add that it feels wrong. For steampunk, I mean.

See, I think part of steampunk's appeal is the way it slows us down.

Steampunk puts us in a world before telephones and jet planes. When

communicating with someone on the other side of town meant dashing off a

postcard. When newspapers lived by the telegraph wire. When

international travelers went by train or ship or even dirigible, and

going around the world took eighty days instead of eighty hours. When a

new advancement in processing speed meant the Royal Mail had worked out

a more efficient sorting system. Our world goes so fast, it's nice to

take a break in a place in which everything goes a little slower.

As a result, it feels like all steampunk should be written at a rolltop

desk on a big, clunky typewriter with a sticky H and a crooked M while a

Victrola plays scratchy music in the background. Manuscripts should be

bundled into boxes tied with brown string. Letters to one's editor

should be scribbled with a fountain pen and dropped into the afternoon

post.

And yet, I flip words into a 2-terrabyte computer with dual-core

processor hooked up to the Internet via high-speed DSL cable modem while

four speakers croon a mix by Danny Elfman, and I toss letters to my

editor into the aether of the Internet It makes me feel out of sorts

and wrong.

Not wrong enough to make write the long way, mind. Anachronism does

have its limits.

But I'm a writer with a good imagination. So when I write steampunk, in

my head my computer becomes a typewriter and my contact lenses become

spectacles. My sweatshirt becomes a tweed jacket and my study with

central heat becomes a drafty garret. My dog and my pot of tea become .

. .

Well. I suppose not everything has to change.

Steven Harper usually lives at http://www.theclockworkempire.com . His

steampunk novel THE DOOMSDAY VAULT, first in the Clockwork Empire

series, hits the stores in print and electronic format November 1.

Published on November 11, 2011 01:00

November 9, 2011

Critiquing Vs. Editing

Renoir, 1889

Editor Jessica Faust at BookEnds Literary Agency blogged on "How I Edit," ending with these words:

As far as I'm concerned you can run with my suggestions or you can

ignore them altogether and go off in your own way. I don't care how you

want to fix the problems I see, I just care that when I read it the next

time those problems/my concerns are gone.

This inspired some thoughts on the differences between critiquing and editing. Both involve handing your precious manuscript, child of your dreams, the darling of your creative muse, to another person and asking what they think of it. In other words, even as we cringe inwardly at the prospect, we have granted permission for them to say things we aren't going to like about it. Of course, we want to hear how much they loved it and all the things we did brilliantly. The point of the exercise, though, is to improve the story.

The most useful things I find in critiques are reader reactions, comments like, "I'm confused," or "This doesn't make sense," or "I don't believe this character would act this way." Or, simply, "Huh? You've got to be kidding!" Snarkiness aside, such comments tell me where there is a problem. The reader may be right about what the problem is, or what they object to may be the tip of an iceberg and the true problem lies elsewhere.

In critique format, I really, really don't want to be told how to fix those problems, and I don't know any writers who do.

Editorial feedback comes at a different stage of creation. We've found those tracks, and the story feels like it's come into its own. (Of course, we could be Way Off Base, but there's still a sense of integrity to the story at this point.) Now there is a thing to become more itself. That's been my experience of working with a good editor -- she or he has the ability to look into the heart of what I'm trying to do, what the story is trying to be, and to see what would make it more so. So that's one major thing -- the story's in a different stage.

The second differences is that -- ideally -- I'm now working as a team with my editor. This does not mean she gets to re-write or re-envision my book. It does mean that she brings expertise to the discussion. I am under no obligation to accept her suggestions of how to change the story. But I'd be throwing away an immensely helpful viewpoint if I didn't at least given those suggestions deep consideration. In my own experience, my editors have been right on in most of this type of feedback, and in those instances in which I objected strongly, I found the discussion led to even better ideas. Regardless, these are issues it behooves me to take seriously, whether I follow my editor's suggestions or come up with my own solutions.

I value both critiquers and editors; I think each brings something important to the maturation of a story. It's just not the same thing, at least for me.

Published on November 09, 2011 01:00

Renoir, 1889

Editor Jessica Faust at BookEnds Litera...

Renoir, 1889

Editor Jessica Faust at BookEnds Literary Agency blogged on "How I Edit," ending with these words:

As far as I'm concerned you can run with my suggestions or you can

ignore them altogether and go off in your own way. I don't care how you

want to fix the problems I see, I just care that when I read it the next

time those problems/my concerns are gone.

This inspired some thoughts on the differences between critiquing and editing. Both involve handing your precious manuscript, child of your dreams, the darling of your creative muse, to another person and asking what they think of it. In other words, even as we cringe inwardly at the prospect, we have granted permission for them to say things we aren't going to like about it. Of course, we want to hear how much they loved it and all the things we did brilliantly. The point of the exercise, though, is to improve the story.

The most useful things I find in critiques are reader reactions, comments like, "I'm confused," or "This doesn't make sense," or "I don't believe this character would act this way." Or, simply, "Huh? You've got to be kidding!" Snarkiness aside, such comments tell me where there is a problem. The reader may be right about what the problem is, or what they object to may be the tip of an iceberg and the true problem lies elsewhere.

In critique format, I really, really don't want to be told how to fix those problems, and I don't know any writers who do.

Editorial feedback comes at a different stage of creation. We've found those tracks, and the story feels like it's come into its own. (Of course, we could be Way Off Base, but there's still a sense of integrity to the story at this point.) Now there is a thing to become more itself. That's been my experience of working with a good editor -- she or he has the ability to look into the heart of what I'm trying to do, what the story is trying to be, and to see what would make it more so. So that's one major thing -- the story's in a different stage.

The second differences is that -- ideally -- I'm now working as a team with my editor. This does not mean she gets to re-write or re-envision my book. It does mean that she brings expertise to the discussion. I am under no obligation to accept her suggestions of how to change the story. But I'd be throwing away an immensely helpful viewpoint if I didn't at least given those suggestions deep consideration. In my own experience, my editors have been right on in most of this type of feedback, and in those instances in which I objected strongly, I found the discussion led to even better ideas. Regardless, these are issues it behooves me to take seriously, whether I follow my editor's suggestions or come up with my own solutions.

I value both critiquers and editors; I think each brings something important to the maturation of a story. It's just not the same thing, at least for me.

Published on November 09, 2011 01:00