Deborah J. Ross's Blog, page 143

April 30, 2013

The Feathered Edge: Ghosts in a Garden, and a Farewell

I've been wondering how I can write about K. D. Wentworth's marvelous, touching story, "The Garden of Swords." I put off this essay until the last, and you'll see why. In the story, a young scullery maid finds solace in the castle garden, in which the slain opponents of the power-mad baron are buried. This is a magical garden, and the ghosts of those swordsmen (and swordswoman!) become the girl's friends, confidantes, teachers, and on occasion her protectors. When I read it over, I feel as if Kathy's ghost is there, too, welcoming us all into her special realm of enchantment and friendship.

I met K. D. Wentworth back in the days when GEnie was a vibrant and interconnected community. I don't know how well the site worked for others, but we sf/f writers took to the bulletin board topics like ducks to supernovae. The various round tables were like rooms in an ongoing convention, with some silly chat and some serious conversations. Professional relationships formed and deepened, and many beginning writers found support and encouragement there. Alas, GEnie with its text-only format went the way of the dinosaur as the clocks ticked over into 2000, but many of the friendships are still going strong.

We met in person a few times, although I did not frequently travel outside the West Coast and she hailed from Oklahoma. I found her as charming and thoughtful in person as online. A number of her short fiction pieces were Nebula Award finalists (the novelette, "Kaleidoscope" 2008, and "Burning Bright" 1997, "Tall One" 1998, and "Born Again" 2005) have been Nebula award finalists. I knew she was one of the writers I wanted for The Feathered Edge.

We met in person a few times, although I did not frequently travel outside the West Coast and she hailed from Oklahoma. I found her as charming and thoughtful in person as online. A number of her short fiction pieces were Nebula Award finalists (the novelette, "Kaleidoscope" 2008, and "Burning Bright" 1997, "Tall One" 1998, and "Born Again" 2005) have been Nebula award finalists. I knew she was one of the writers I wanted for The Feathered Edge. True to her high professional standards, she sent me a story that is extraordinary. In clear prose and straightforward narrative, she managed to reach into my heart. "In the Garden of Swords" fits loosely within the theme of elegant romantic fantasy, a ghost-story-with-a-twist, sword and sorcery, but it is also a story of how love and kindness, strength and truth, transcend death. Whenever I re-read it, I hear Kathy's literary voice still spinning out tales of wonder and hope.

Kathy died in April 2012. I had no idea she was so ill. We weren't close, except in the sense that all writers who love fantasy and whose professional paths cross are close.

Wherever you are, Kathy, thank you for your marvelous stories. The world is richer for having had you in it.

Published on April 30, 2013 01:00

April 23, 2013

The Feathered Edge: An Outlander Takes on Masks and Feathers

Writers form communities in various ways, and I think there is no finer, more supportive or interwoven community than people who read and write fantasy and science

Writers form communities in various ways, and I think there is no finer, more supportive or interwoven community than people who read and write fantasy and science fiction. Sometimes it feels as if there really are only about 300 of us,

and we mill around, meeting one another through yet another different

connection. Just as I wouldn't have met Rosemary Hawley Jarman except

through Tanith Lee, who I had met through Norilana's publisher, I

wouldn't have had the joy of editing Samantha Henderson's "Outlander" if

I had not been friends and colleagues with Sheila Finch (whose

"Fortune's Stepchild" also appears in The Feathered Edge).

Samantha was such a discovery that I searched out her other work. It came as no surprise that's she's also a poet and winner of the Rhysling Award, or that her fiction spans a spectrum from hilarious to very strange-and-dark, with a little steampunk thrown in, too. As one whose own poetry efforts are best forgotten, I'm a bit in awe of writers who can do this well, and even more so when they, like Samantha, are adept at prose stories as well.

"Outlander" has many of the superficial trappings we've seen before, in the adventures of a man from the "sticks" who is seen by members of a caste-bound aristocracy as uncouth and dull-witted, although physically strong. We expect to find him in the dueling arena instead of the drawing room, and so we do, but not for the reasons we -- and the narrator -- assume. The story is told from the point of view of a member of the nobility who, while unable to see beyond his own prejudices, provides a transparent window for the reader's experience. Throughout the story, from the very first sentence, runs a vein of wit, not to mention keen social commentary. The result is a delightful mixture of humor and romance, with a twist at the end.

And I'm not saying any more about it, lest I spoil the surprise.

You can listen to this marvelous story on Podcastle.

Published on April 23, 2013 01:00

April 22, 2013

Music and grief

Our elderly and Highly Opinionated tortoiseshell cat, Cleopatra, died Saturday morning. She's made it to her 20th birthday last month, which astonished us all. Privately, I think she wasn't about to let the dog outlast her. (Oka, our wonderful German Shepherd Dog, died on Wednesday.)

It's a bit much to take in, the loss of two pets within a week. We're keeping an eye on the black cat who was Oka's buddy. He wanders around the house, clearly looking for Oka. (He still has a cat friend, one-eyed lady pirate Gayatri.)

I've been studying piano as an adult for about 7 or 8 years now. I play mostly classical, but add in fun stuff, too, like music from The Lord of the Rings. Earlier this spring, I began working on "Into the West." It's an easy setting, and it's flowing nicely, although in a key I can't sing. That's okay. Since Oka died, I've played it with tears streaming down my face. "All dogs pass...into the west." The music brings up grief in a way words can't. A healing way, a gentle way that lets me go as deep as is right for me at the moment. It's not the same as listening to music because I'm inside of it, I'm creating it right now in this moment and no two performances are ever the same. It reminds me poignantly of how pets live in the "now."

Today's practice was a little different. One of my serious pieces is the 3rd Gymnopedie by Satie. The tempo is Lento e grave. I slowed it a bit, focusing on the full tone of each chord, and realized I was playing it for both animals. The right hand melody soars above the funeral bass rhythm in that aeolian mode. Sweet and sad and profoundly honoring the memory of these friends-in-fur.

It's a bit much to take in, the loss of two pets within a week. We're keeping an eye on the black cat who was Oka's buddy. He wanders around the house, clearly looking for Oka. (He still has a cat friend, one-eyed lady pirate Gayatri.)

I've been studying piano as an adult for about 7 or 8 years now. I play mostly classical, but add in fun stuff, too, like music from The Lord of the Rings. Earlier this spring, I began working on "Into the West." It's an easy setting, and it's flowing nicely, although in a key I can't sing. That's okay. Since Oka died, I've played it with tears streaming down my face. "All dogs pass...into the west." The music brings up grief in a way words can't. A healing way, a gentle way that lets me go as deep as is right for me at the moment. It's not the same as listening to music because I'm inside of it, I'm creating it right now in this moment and no two performances are ever the same. It reminds me poignantly of how pets live in the "now."

Today's practice was a little different. One of my serious pieces is the 3rd Gymnopedie by Satie. The tempo is Lento e grave. I slowed it a bit, focusing on the full tone of each chord, and realized I was playing it for both animals. The right hand melody soars above the funeral bass rhythm in that aeolian mode. Sweet and sad and profoundly honoring the memory of these friends-in-fur.

Published on April 22, 2013 13:44

April 19, 2013

Space Opera Fridays Revisits: Is Darkover Space Opera?

This post from a couple of years ago still gets viewers, so in case you missed it, I'm giving it another day of blog-glory. With the recent publication of The Children of Kings, which takes place entirely on Darkover, but does involve things going 'splody in space, it seems appropriate.

My husband, sf writer Dave Trowbridge, and I were discussing the appeal of space opera at breakfast, what it is and why it appeals. Basically, space opera is a type of science fiction set on a large scale, highly dramatic and sometimes melodramatic. It tends to have military elements -- huge battles upon which hinge the fate of galactic empires, that sort of thing. Although wikipedia says it has nothing to do with the musical form, I think that reflects their own ignorance. What space opera and musical opera have in common is being larger than life, or rather brighter and more intense than life. Opera was, after all, the epitome high-tech special-effects knock-your-socks-off entertainment for centuries. Music, lyrics, sets, and costumes, not to mention trap doors and wire harnesses, exotic animals and fireworks, all enhanced one another. But that's another topic.

We agreed that we love the grand scope of such tales, but that it needs to be balanced by emotionally intimate moments. The same is true, for me at least, in epic fantasy. Monstrous dark forces are threatening the entire world, volcanoes exploding by the thousands, rivers of fire and poison...and then a detail in the characters that's so human, it touches my heart, not just my things-go-boom adrenalin endorphins.

Which brings me to Darkover.

Somewhere along the line, the romantic sensibilities of the early Darkover novels took on the feeling of fantasy. After all, people were riding horses and thwacking each other with swords. Laran took on the aspect of semi-magic, even the terminology ("spells"). But there is something grand and opera-like about many of the stories. Think of Stormqueen! or The Heritage of Hastur, landscapes rent with supernaturally-charged storms, space ships bursting into flame, mental powers concentrated in crystals and then bursting out, wild and uncontrolled...characters faced with terrible choices and even more painful sacrifices. One of the joys of working with Marion on the "Clingfire" trilogy was creating a big, overarching story that spanned generations and came to a resounding climax with the adoption of the Compact. Verdi would have adored it. Not to mention Mozart! (I can't help wondering what the man who composed The Magic Flute would have done with Darkover.)

Marion was a life-long opera enthusiast.As a young woman, she'd wanted to be an opera singer, and she never lost her love of it. One of my favorite memories of her was going together to hear Puccini's Manon Lescaut at the San Francisco Opera. I wonder how much of that love of opera -- music, words, color and movement coming together to make a whole greater than the parts -- helped shape the world of the Bloody Sun.

Darkover may be only one planet, and hence the term "space" may be subject to question, but is it space opera? What do you think?

Published on April 19, 2013 01:00

April 18, 2013

Good night, sweet boy

Most of my blogs are about writing and writers, my projects and those of others. But I want to step aside from that and share a very special life and passing. For those of us who are dog people, the short years we share with a canine companion enrich our lives immeasurably. Our sweet, brave German Shepherd Dog, Oka, died peacefully yesterday. He was 12 1/2, quite old for that breed, had had been battling lymphoma and degenerative myelopathy. We'd hoped to have him for a little while longer, but he developed leukemia, lost the ability to walk, and most likely had an embolism and a stroke. The vet came out to our house and he slipped away with "his people" holding him and talking to him. Also, "his cats" - all 3 gathered around, especially Oka's "best buddy," who cuddled up next to him when it was all over.

Here are a few images to share with you:

Oka at 8 weeks. The green coloring in his right ear is the Schaferhundverein breed

tattoo, certifying that he really is a German

Shepherd Dog (i.e. both his parents were Schutzhund titled; in fact, his

father was the Weltsieger: the world champion).

Attempting to wrestle the cat toy into submission.

About 1 year old, hiking in our area. He would have made a super search-and-rescue dog, he was so focused on scent. You can see how he's "tracking" naturally.

About 2, getting his basic obedience title. You can see the bond between Dave and Oka."What next, Dad? What do we get to play next?"

Herding his hard rubber horse ball. He would do this for hours, bringing the ball back so we could roll it away for him and barking at it to let it know who was boss. We tend to forget that German Shepherd Dogs are indeed sheepherding dogs. This is his spherical "sheep."

I think he's 3 or 4 in this picture. This is how I'll remember him, a loyal, loving friend, steady in temperament and eager to do anything we asked of him.

Here are a few images to share with you:

Oka at 8 weeks. The green coloring in his right ear is the Schaferhundverein breed

tattoo, certifying that he really is a German

Shepherd Dog (i.e. both his parents were Schutzhund titled; in fact, his

father was the Weltsieger: the world champion).

Attempting to wrestle the cat toy into submission.

About 1 year old, hiking in our area. He would have made a super search-and-rescue dog, he was so focused on scent. You can see how he's "tracking" naturally.

About 2, getting his basic obedience title. You can see the bond between Dave and Oka."What next, Dad? What do we get to play next?"

Herding his hard rubber horse ball. He would do this for hours, bringing the ball back so we could roll it away for him and barking at it to let it know who was boss. We tend to forget that German Shepherd Dogs are indeed sheepherding dogs. This is his spherical "sheep."

I think he's 3 or 4 in this picture. This is how I'll remember him, a loyal, loving friend, steady in temperament and eager to do anything we asked of him.

Published on April 18, 2013 17:26

April 16, 2013

The Feathered Edge Ventures into an Algerian Brothel

As I've discussed in earlier posts, one of the joys of editing is getting an inside view of another writer's creative process. Sometimes this comes in the reading process, but more likely it happens during the editorial discussions with their give-and-take. Often a good editor can pinpoint places where what is on the page does not fully or accurately convey the writer's intention. We then become conspirators whose goal is to make the story the best incarnation of that authorial vision. When I began editing, I had no idea that I'd also get to witness yet another joy of short fiction -- the inception and development of a series of related stories that trace not only the adventures but the emotional development of a character.

The first anthology I edited was Lace and Blade (Norilana Books, 2008), and I asked Diana L. Paxson, who I'd known about as long as I'd known Marion, to send me a story. The premise of the anthology was elegant, sensual sword and sorcery of the "Scarlet Pimpernel With Magic" or Alfred Noyse's poem, "The Highwayman," variety. Diana gave me a dashing young hero, Baron Claude

DeLorme, newly come into his title, and promptly took a right angle turn from the expected European-centered fantasy by sending him off to Brazil to claim an

DeLorme, newly come into his title, and promptly took a right angle turn from the expected European-centered fantasy by sending him off to Brazil to claim an emerald mine as his inheritance. The magic that imbues "The Crossroads"

is anything but conventional, but this adventure was only the beginning.

If "The Crossroads" taught Claude about Brazilian/African magic, then

his next story (in Lace and Blade 2) brought him back to Paris to face a very different sort of supernatural evil in "The Crow." One of the things that most appealed to me in this second story is how, although it stands perfectly well on its own, it's a true, developmental continuation of the previous story. The Claude DeLorme who arrived in Brazil is not the same man battling an occult cabal in Paris...and not the same man who arrives in Algiers.

"Blue Velvet" is not an easy read, for Claude's adversary is a sadistic, equal-opportunity-rapist slave-master, and Diana doesn't pull any punches. As in the previous stories, Claude finds himself in danger that is both physical and magical. But he is not without resources -- his innate compassion, the loyalty he shares with his friends, and his hard-won understanding of the supernatural. At the end, Diana suggests that Claude might next be off to West Africa. I hope she has the chance to write that story -- and that I have the chance to edit it!

Published on April 16, 2013 01:00

April 12, 2013

Space Opera Fridays: Dave Trowbridge on Space Opera and the Siege of Vienna

Space Opera and the Siege of Vienna: the Archetypal Perspective

In their 2003 article How Shit Became Shinola: Definition and Redefinition of Space Opera ,

David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer defined modern space opera as

“colorful, dramatic, large scale science fiction adventure, competently

and sometimes beautifully written, usually focused on a sympathetic,

heroic central character, and plot action … and usually set in the

relatively distant future and in space or on other worlds,

characteristically optimistic in tone.”

It would be hard to improve on that definition using words (although I

could write an entire blog post concerning the exceptions that prove

the rule—and maybe I will one of these days), but I can show you what I

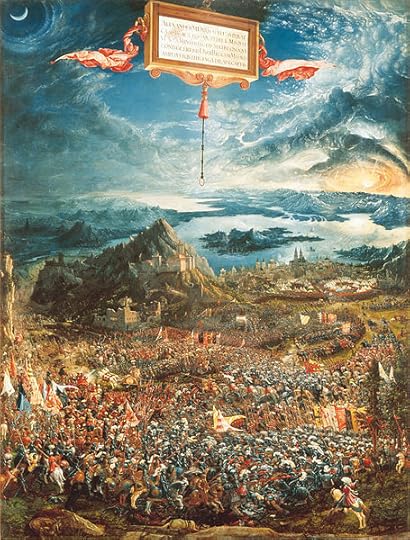

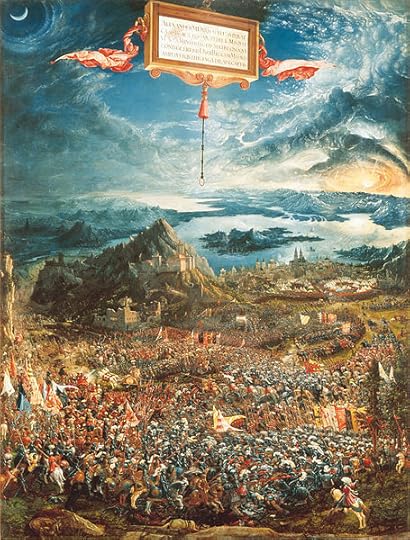

go to space opera for with a single image.

That’s the Alexanderschlacht (The Battle of Alexander at Issus)

by Albrecht Altdorfer, which was commissioned in 1528 by William IV,

Duke of Bavaria. Altdorfer’s conception of the painting was almost

certainly heavily influenced by the defeat of the Suleiman the

Magnificent at the Seige of Vienna the next year, and his execution of

the commission epitomizes what I look for in space opera, and what

Sherwood Smith and I tried to do in our space opera Exordium , which is being reissued in a revised edition by Book View Café.

Alexanderschlacht portrays the victory of Alexander over

Darius III in a battle that was the beginning of the end for the Persian

Empire, which fell in 330 BCE with the death of Darius and Alexander’s

assumption of his title as king, assuring the Hellenization of the Near

East. The work’s composition is thought to echo the four-kingdom

eschatology of the Book of Daniel—Babylon (note the distant Tower of

Babylon at the left side of the painting, under the crescent moon),

Persia, Greece, and Rome), with Alexander’s victory representing the

triumph of Greece over Persia, and echoing the hope that the relief of

Vienna represented the triumph of Christendom (i.e., Rome) over Islam.

The description of the painting in Wikipedia starts by noting the “impossible viewpoint” of the painting, but that’s precisely what the Alexanderschlacht

shares with space opera, and why it can serve as the

picture-worth-a-thousand-words definition of the genre. Rather than

“impossible viewpoint,” I’d call it the “archetypal perspective:” a

close-up and even intimate view of heroic characters against a

highly-detailed yet sweeping background meant to illustrate the

fundamental struggle between good and evil, light and darkness. That’s

what I go to space opera for.

Look at how Altdorfer laid out the action: the incredibly-detailed

foreground that highlights the two antagonists: Alexander sweeping in

from the West (out of the Sun) at the head of his Companions, pursuing

his defeated enemy Darius on his chariot fleeing to the East (towards

the Moon), all surrounded by a swirl of cavalry and foot soldiers. All

this is portrayed in a physically impossible perspective that rises up

past the chaos of battle to portray the Mediterranean Sea, Cyprus, the

Nile, the Red Sea, and eventually encompasses three continents (Europe,

Asia, and Africa) and reveals the curvature of the earth at the horizon,

with an apocalyptic sky dominating the whole. (And if you tilted the

suspended description panel at the top of the painting back away from

the viewer…Star Wars, anyone?)

The painting is dense with symbolism and detail, ranging from

unrealistic ones like ladies in court dress at the edge of the battle,

to highly-archetypal ones like the Sun and crescent Moon. It’s a visual

feast that invites zooming in and out, one that you can return to again

and again, gaining something new each time, just like re-reading a big,

chewy space opera (or epic fantasy, for that matter: check out my

co-writer Sherwood Smith’s blog post

on that subject). And really, one need only change a few details in the

painting, add some spaceships, substitute blasters for lances, pull

back a little farther so the Earth is just one planet in an even bigger

panorama, and, voila: space opera.

Basically, I think space opera, like epic fantasy, is simply the way

most people see the world on any scale, from the personal to the grand

sweep of history: as a story with a goal, a story where every pattern,

every detail, points to deeper meaning. The dark side of this

perspective is conspiracy theory; the light side, great art.

What do you think?

In their 2003 article How Shit Became Shinola: Definition and Redefinition of Space Opera ,

David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer defined modern space opera as

“colorful, dramatic, large scale science fiction adventure, competently

and sometimes beautifully written, usually focused on a sympathetic,

heroic central character, and plot action … and usually set in the

relatively distant future and in space or on other worlds,

characteristically optimistic in tone.”

It would be hard to improve on that definition using words (although I

could write an entire blog post concerning the exceptions that prove

the rule—and maybe I will one of these days), but I can show you what I

go to space opera for with a single image.

That’s the Alexanderschlacht (The Battle of Alexander at Issus)

by Albrecht Altdorfer, which was commissioned in 1528 by William IV,

Duke of Bavaria. Altdorfer’s conception of the painting was almost

certainly heavily influenced by the defeat of the Suleiman the

Magnificent at the Seige of Vienna the next year, and his execution of

the commission epitomizes what I look for in space opera, and what

Sherwood Smith and I tried to do in our space opera Exordium , which is being reissued in a revised edition by Book View Café.

Alexanderschlacht portrays the victory of Alexander over

Darius III in a battle that was the beginning of the end for the Persian

Empire, which fell in 330 BCE with the death of Darius and Alexander’s

assumption of his title as king, assuring the Hellenization of the Near

East. The work’s composition is thought to echo the four-kingdom

eschatology of the Book of Daniel—Babylon (note the distant Tower of

Babylon at the left side of the painting, under the crescent moon),

Persia, Greece, and Rome), with Alexander’s victory representing the

triumph of Greece over Persia, and echoing the hope that the relief of

Vienna represented the triumph of Christendom (i.e., Rome) over Islam.

The description of the painting in Wikipedia starts by noting the “impossible viewpoint” of the painting, but that’s precisely what the Alexanderschlacht

shares with space opera, and why it can serve as the

picture-worth-a-thousand-words definition of the genre. Rather than

“impossible viewpoint,” I’d call it the “archetypal perspective:” a

close-up and even intimate view of heroic characters against a

highly-detailed yet sweeping background meant to illustrate the

fundamental struggle between good and evil, light and darkness. That’s

what I go to space opera for.

Look at how Altdorfer laid out the action: the incredibly-detailed

foreground that highlights the two antagonists: Alexander sweeping in

from the West (out of the Sun) at the head of his Companions, pursuing

his defeated enemy Darius on his chariot fleeing to the East (towards

the Moon), all surrounded by a swirl of cavalry and foot soldiers. All

this is portrayed in a physically impossible perspective that rises up

past the chaos of battle to portray the Mediterranean Sea, Cyprus, the

Nile, the Red Sea, and eventually encompasses three continents (Europe,

Asia, and Africa) and reveals the curvature of the earth at the horizon,

with an apocalyptic sky dominating the whole. (And if you tilted the

suspended description panel at the top of the painting back away from

the viewer…Star Wars, anyone?)

The painting is dense with symbolism and detail, ranging from

unrealistic ones like ladies in court dress at the edge of the battle,

to highly-archetypal ones like the Sun and crescent Moon. It’s a visual

feast that invites zooming in and out, one that you can return to again

and again, gaining something new each time, just like re-reading a big,

chewy space opera (or epic fantasy, for that matter: check out my

co-writer Sherwood Smith’s blog post

on that subject). And really, one need only change a few details in the

painting, add some spaceships, substitute blasters for lances, pull

back a little farther so the Earth is just one planet in an even bigger

panorama, and, voila: space opera.

Basically, I think space opera, like epic fantasy, is simply the way

most people see the world on any scale, from the personal to the grand

sweep of history: as a story with a goal, a story where every pattern,

every detail, points to deeper meaning. The dark side of this

perspective is conspiracy theory; the light side, great art.

What do you think?

Published on April 12, 2013 01:00

April 11, 2013

One World, Many Stories

From

Fromtime to time, I take my pile of newly-read books and post reviews. As I

sat down recently to do this, I realized that not a single one of them

was a true stand-alone. They were either the first book at led to others

set in the same world (Kage Baker’s The Garden of Iden, her debut novel and also the first “Company” novel; Garth Nix’s Sabriel, the first book of the “Abhorsen” trilogy); or they were middle books in a series (Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe’s Prey and Sherwood Smith’s Blood Spirits). The

Baker and the Nix novels differ in that Baker’s story is complete in

itself. No previous knowledge of this world is necessary and the reader

is left in a place of rest. Sabriel, on the other hand, clearly is part of a defined trilogy – one long story arc, with only a partial resolution at the end.

The Cornwell is clearly part of an ongoing series that follows one primary character through a certain historical time period, with

The Cornwell is clearly part of an ongoing series that follows one primary character through a certain historical time period, withoccasional minor characters, both allies and villains. It is

interesting because Cornwell’s first “Sharpe” book began in the middle

of the hero’s career. After writing a number of novels, he returned to

an earlier time and also “between times,” novels interpolated between

previously-published episodes. Each book centers on a battle or other

specific, time-limited military event in the Napoleonic Wars and

adjacent time periods, and although it is enjoyable to meet old

“friends,” there is little sense of development in plot or tension from

one story to the next. True, the central character matures with

experience, but his personal arc is not the driving force of the novels.

The escalating tension, climax, and outcome of each battle provide the

structure for the plot.

Smith’s Blood Spirits is the middle book of a three-book series (Coronets and Steel; Blood Spirits; Revenant Eve). The “Dobrenica”

Smith’s Blood Spirits is the middle book of a three-book series (Coronets and Steel; Blood Spirits; Revenant Eve). The “Dobrenica”books are not a true trilogy, nor are they a sequence of independent

episodes. Enough information is provided so that it is not absolutely

necessary to read the books in order, but it is definitely better to do

so. There is a degree of continuing momentum from one book to the next,

so the books have less of an episodic nature than do the Cornwell

novels.

I’ve been thinking about the whole issue of book “series”

because for the last dozen years I have been continuing the “Darkover”

series, created by Marion Zimmer Bradley. Especially in the early years,

Marion insisted that each book had to stand on its own and that they

could be read in any order. I think that’s a laudable goal, and for the

most part, the early and middle Darkover books achieved it. Eventually,

she began writing books that, while they may not have been part of a

single overall story line, were most definitely sequels. Readers may

argue with me, but I think that novels such as Thendara House and City of Sorcery fare less well if they are not considered as an extended story line begun with The Shattered Chain. To a lesser extent, Sharra’s Exile (which was itself a rewrite of The Sword of Aldones, a very early Darkover novel) is a sequel to The Heritage of Hastur.

The first project I worked on (with Marion, in the last year of her life) was conceived as a trilogy (“Clingfire”), in that we wanted

The first project I worked on (with Marion, in the last year of her life) was conceived as a trilogy (“Clingfire”), in that we wantedto relate a very large story, how the Comyn came to adopt the Compact,

which forbade the use of distance weapons, whether physical or psychic.

As it turned out the first and second volumes (The Fall of Neskaya and Zandru’s Forge)

were separated by a generation as we set up the political background,

the alliances and feuds that would come together in a catastrophic

battle in the final book. This had the effect of beginning the second

book with a mostly-new set of characters, giving the trilogy two

beginnings and the first book the character of a stand-alone.

In writing the next two books (The Alton Gift, Hastur Lord),

I struggled with the demands of placing each story historically between

already-published works and the ideal goal of making it entire in

itself. Hastur Lord was based around a manuscript Marion had

written when she was very ill, so the time placement and central plot

were her conception; it’s one of those “here’s what happened between

Book A and Book B” stories. The appeal of such stories is that

established readers who love the world and its characters are happy with

“fill in the blanks” stories, but the drawback is that both beginning

and end points are fixed. Marion had concocted a few surprises to

counteract the resulting predictability, but even so, I appreciated the

challenge Cornwell faced in going “backward in time” in the life of

Richard Sharpe because we already know Sharpe is going to not only

survive, but rise through the ranks.

For the most recent Darkover book, The Children of Kings,

For the most recent Darkover book, The Children of Kings,I made a concerted effort to create a stand-alone novel, one that would

be a friendly welcome to new readers unfamiliar with the world, without

disappointing long-time fans who look forward to playing with their

favorite characters. In this, I was returning to Marion’s initial vision

of the Darkover series – unrelated or minimally-dependent novels that

draw on the same world-building and sources of conflict. I used

characters who were either original or played very minor roles in

previous novels, and sent them on a journey to areas of the planet that

Marion had touched upon only lightly. The generalized tension that

permeated the early Darkover novels – the clash between cultures – is

not resolved, and indeed is not resolvable, but this specific set of

circumstances and the resulting crisis is. The reader does not have to

have read any previous Darkover novels to understand what is going on,

who these people are and what their values are, and hopefully if readers

are screaming for more, it’s because they love the world, not because

they want to know how the story ends.

This reminds me of a

conversation I had with Margaret Chang, who collaborates with Harry

Campion as M. H. Mead. They write computer/virtual-reality based science

fiction and call their collective work a set rather than a series. Each

story takes place in the same world in approximately the same time

period, and is complete in itself. Minor characters from one story may

appear in the next, and in terms of time-line, there are occasional

references to events, but in the way any background or history might be

included.

This summer, the first volume of my original fantasy trilogy, The Seven-Petaled Shield, will be released by DAW. It is a true trilogy,

This summer, the first volume of my original fantasy trilogy, The Seven-Petaled Shield, will be released by DAW. It is a true trilogy,one long story arc with incomplete resolution at the end of the first

two books. Fortunately, DAW is committed to bringing out the subsequent

volumes at fairly short intervals so I will not be obliged to hire

bodyguards to protect me from frustrated readers, demanding to know how I

could make them wait to find out what happens next. The trilogy is

itself based on a series of short stories that I wrote for the Sword & Sorceress

anthologies. I’d begun with a tale based in the conflict between the

Romans and the Scythians, each culture with its own magic, and the more I

wrote, the larger the landscape and its possibilities became. I’ll be

bringing these four short stories together in a collection, Azkhantian Tales, in June from Book View Café.

Which

brings me to the point of writing a series, or sequels, or a “set” of

stories. Sometimes when we create a world, whether it is for a novel or a

shorter piece, we realize how much of it exists “off the page” and we

come to love it so much we want to go explore. Or to stay in the same

location or time period and delve more deeply into it. Or simply to run

away to our favorite imaginary place with our favorite characters. These

multi-novel variations allow us to do that, to create related

stories, to use and build upon our vision of a world. Incidentally, I

have been known to bribe secondary characters who are threatening to run

away with the plot with their own stories. Knowing that I can “spin

off” such tales helps me to focus on this story, to keep plot and

subplot from burgeoning into a shapeless and planet-consuming proteus.

Sometimes I find that secondary characters or places mentioned only in

passing turn out to be more interesting, more complex and ambivalent,

dark and transcendent, than my original conceptions.

The pitfall

of writing a series (etc.) when a writer is still new and learning craft

is that working in an established world means we don’t create new ones,

and world-building is a skill that improves with practice. If your

first story is the only one you ever want to write, that’s less of a

problem than if you are like me and your head is filled with a spectrum

of story ideas, each screaming to be told. In that case, I think you do

yourself a disservice in committing years of your formative literary

life to one vision, instead of pushing to make each new world more

complex and fascinating. One of the benefits of writing short fiction is

the relatively small time investment in each story, as compared to

working at novel length. Mistakes cost a far smaller fraction of your

overall career, and each story is an opportunity to start fresh, aim

higher, and twist reality in a different way.

Published on April 11, 2013 01:00

April 10, 2013

WWW Wednesday 4-10-2013

WWW Wednesday. This meme is from shouldbereading.

To play along, just answer the following three (3) questions…

• What are you currently reading?

• What did you recently finish reading?

• What do you think you’ll read next?

Currently reading: Charles de Lint’s Muse and Reverie: A Newford Collection.

I love de Lint’s work. A couple of paragraphs into each story, some

undefined tension in me sighs happily and lets go. I suspect it’s the

effortlessness of his craft, or maybe just that I read his prose with a

different part of my mind than I write my own. I’ve long given up trying

to analyze why this is so.

I’ve

I’ve

been overworking these past few months, so I crave refreshment of the

spirit. At bedtime I’m slowly savoring my way through The Book of Words: Talking Spiritual Life, Living Spiritual Talk by Lawrence Kushner. Kushner (there are two – the other is Harold) was my introduction to Jewish mysticism. I re-read Honey From the Rock

every few years and get even more out of it. I find I sleep better and

am kinder and yet stronger during the day if I enrich the gentle

transition to sleep. I read a little in Hebrew to signal to my brain

that this is now a time of rest, a sacred time. Then I switch to English

because although I can sound out the words in Hebrew, I’m very, very

far from fluent in it. I read:

Blessings give reverent and routine voice to our conviction that

life is good, one blessing after another. Even, and especially when life

is cold and dark. Indeed to offer blessings at such times may be our

only deliverance.

… and my spirit gives that sigh of relief, just the way my writer’s

mind does when I read de Lint. No matter what sorrows the day has

brought, in this moment they are over. I can rest easy. Tomorrow I will

begin the struggle anew.

Recently finished reading: For fun and delight: Sherwood Smith’s Blood Spirits; Kage Baker’s In the Garden of Iden (which I think is the first Company novel), a novel-in-beta-form by Juliette Wade , a rising star in science fiction, For Love, For Power. And at night, Ethics for a New Millennium

, a rising star in science fiction, For Love, For Power. And at night, Ethics for a New Millennium

by the Dalai Lama. It took me a long time to read the latter, as I

wanted to let each thought sink in; small bites, small moves.

What I’ll likely read next: I’m up for more Molly Gloss, who is a terrific writer; maybe The Jump-Off Creek or rereading The Hearts of Horses. I’ve been saving Carol Berg’s The Soul Mirror

and now’s a great time. I have the next Dobrenica book, also several

Caitlin Brennan/Judith Tarr novels. And if life gets too crazy, I can

always dive into the next Sookie Stackhouse. For bedtime, maybe

rereading Jonathan Sacks To Heal A Fractured World: The Ethics of Responsibility or Elyse Goldstein ReVisions: Seeing Torah Through A Feminist Lens. Or Mary Oliver’s poetry, which always speaks to me.

To play along, just answer the following three (3) questions…

• What are you currently reading?

• What did you recently finish reading?

• What do you think you’ll read next?

Currently reading: Charles de Lint’s Muse and Reverie: A Newford Collection.

I love de Lint’s work. A couple of paragraphs into each story, some

undefined tension in me sighs happily and lets go. I suspect it’s the

effortlessness of his craft, or maybe just that I read his prose with a

different part of my mind than I write my own. I’ve long given up trying

to analyze why this is so.

I’ve

I’vebeen overworking these past few months, so I crave refreshment of the

spirit. At bedtime I’m slowly savoring my way through The Book of Words: Talking Spiritual Life, Living Spiritual Talk by Lawrence Kushner. Kushner (there are two – the other is Harold) was my introduction to Jewish mysticism. I re-read Honey From the Rock

every few years and get even more out of it. I find I sleep better and

am kinder and yet stronger during the day if I enrich the gentle

transition to sleep. I read a little in Hebrew to signal to my brain

that this is now a time of rest, a sacred time. Then I switch to English

because although I can sound out the words in Hebrew, I’m very, very

far from fluent in it. I read:

Blessings give reverent and routine voice to our conviction that

life is good, one blessing after another. Even, and especially when life

is cold and dark. Indeed to offer blessings at such times may be our

only deliverance.

… and my spirit gives that sigh of relief, just the way my writer’s

mind does when I read de Lint. No matter what sorrows the day has

brought, in this moment they are over. I can rest easy. Tomorrow I will

begin the struggle anew.

Recently finished reading: For fun and delight: Sherwood Smith’s Blood Spirits; Kage Baker’s In the Garden of Iden (which I think is the first Company novel), a novel-in-beta-form by Juliette Wade

, a rising star in science fiction, For Love, For Power. And at night, Ethics for a New Millennium

, a rising star in science fiction, For Love, For Power. And at night, Ethics for a New Millenniumby the Dalai Lama. It took me a long time to read the latter, as I

wanted to let each thought sink in; small bites, small moves.

What I’ll likely read next: I’m up for more Molly Gloss, who is a terrific writer; maybe The Jump-Off Creek or rereading The Hearts of Horses. I’ve been saving Carol Berg’s The Soul Mirror

and now’s a great time. I have the next Dobrenica book, also several

Caitlin Brennan/Judith Tarr novels. And if life gets too crazy, I can

always dive into the next Sookie Stackhouse. For bedtime, maybe

rereading Jonathan Sacks To Heal A Fractured World: The Ethics of Responsibility or Elyse Goldstein ReVisions: Seeing Torah Through A Feminist Lens. Or Mary Oliver’s poetry, which always speaks to me.

Published on April 10, 2013 11:05

April 9, 2013

The Feathered Edge Tackles Norse Mythology

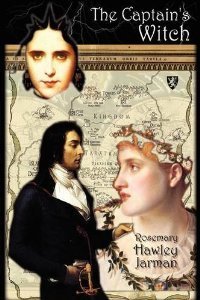

My relationship with Rosemary Hawley Jarman is all Tanith Lee's fault. Which is actually a good thing. In my more whimsical moments, I suspect there is a secret society of British fantasy authors who, if they don't actually know one another, enjoy only a single degree of separation. (Sometimes that degree is me, and it's both odd and delightful to be performing introductions across the Atlantic between people who live on the same island, but that's another story.) So when Tanith introduced me to Rosemary, Rosemary and I also had another connection, which is that the small press Norilana was publishing both the first anthology I'd edited and Rosemary's romantic fantasy, The Captain's Witch. Her 1971 novel, We Speak No Treason, featured the much maligned King Richard III.

Rosemary is one of the authors who teach me about editing. It's quite a humbling experience to work with writers with far more years and experience than I have. I feel privileged to get a peek into their

"Ever since my first glimpse of fjord and glacier," she writes, "the Norse legends have become emotionally significant. The magical sword I see as the archetype of mortal striving and desire. In this story I have departed from the Wagnerian tradition and it is a woman who, like the hero Siegfried, renders the broken weapon into a sacred force. The Ring has elements of the Sleeping Beauty, the longed-for princess, and the flames symbolise the ordeal to be passed through in search of fulfillment. Nothing changes, even today, so long as love is pure."

own processes. More than that, I've come to see that editing-according-to-Deborah is like a dance. The author does her best to put her vision (or, as Rosemary puts it, her "creative plan") into words on a page, and I do my best to discern the heart of that story and, upon occasion, to make suggestions aimed at realizing that heart more fully. Sometimes I'm spot-on, but at other times I can misperceive or get overly enthusiastic about what I think the story is about (as opposed to what the author intended). I know I'm on the right track when I'm able to judge when to drop it, what is the author's creative prerogative, and when to press a question, when there's something unresolved that in my judgment impairs the story from reaching its potential. Working with Rosemary, especially seeing how she thinks in terms of a "creative plan" has given me great insight into the flexibility needed for good editing. This was especially helpful with "Fire and Frost and Burning Rose" because she's taken a mythology and shaped it in unexpected ways.

As with Rosemary's other stories, it's best to leave your expectations at the door when you venture forth into her world. Just when you think you have it figured out -- oh, this character is this Norse god, and so forth -- she spins the story around and you're not in Kansas -- er, Norway -- any more, but in a realm that sometimes playful, sometimes tragic, sometimes erotic, always refreshing.

Rosemary lives in an antique stone cottage between sea and mountain in West Wales, which strikes me as an exactly perfect place in which to write her stories.

Published on April 09, 2013 01:00