Space Opera Fridays: Dave Trowbridge on Space Opera and the Siege of Vienna

Space Opera and the Siege of Vienna: the Archetypal Perspective

In their 2003 article How Shit Became Shinola: Definition and Redefinition of Space Opera ,

David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer defined modern space opera as

“colorful, dramatic, large scale science fiction adventure, competently

and sometimes beautifully written, usually focused on a sympathetic,

heroic central character, and plot action … and usually set in the

relatively distant future and in space or on other worlds,

characteristically optimistic in tone.”

It would be hard to improve on that definition using words (although I

could write an entire blog post concerning the exceptions that prove

the rule—and maybe I will one of these days), but I can show you what I

go to space opera for with a single image.

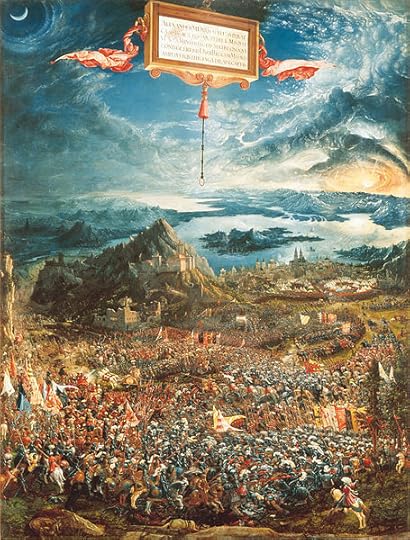

That’s the Alexanderschlacht (The Battle of Alexander at Issus)

by Albrecht Altdorfer, which was commissioned in 1528 by William IV,

Duke of Bavaria. Altdorfer’s conception of the painting was almost

certainly heavily influenced by the defeat of the Suleiman the

Magnificent at the Seige of Vienna the next year, and his execution of

the commission epitomizes what I look for in space opera, and what

Sherwood Smith and I tried to do in our space opera Exordium , which is being reissued in a revised edition by Book View Café.

Alexanderschlacht portrays the victory of Alexander over

Darius III in a battle that was the beginning of the end for the Persian

Empire, which fell in 330 BCE with the death of Darius and Alexander’s

assumption of his title as king, assuring the Hellenization of the Near

East. The work’s composition is thought to echo the four-kingdom

eschatology of the Book of Daniel—Babylon (note the distant Tower of

Babylon at the left side of the painting, under the crescent moon),

Persia, Greece, and Rome), with Alexander’s victory representing the

triumph of Greece over Persia, and echoing the hope that the relief of

Vienna represented the triumph of Christendom (i.e., Rome) over Islam.

The description of the painting in Wikipedia starts by noting the “impossible viewpoint” of the painting, but that’s precisely what the Alexanderschlacht

shares with space opera, and why it can serve as the

picture-worth-a-thousand-words definition of the genre. Rather than

“impossible viewpoint,” I’d call it the “archetypal perspective:” a

close-up and even intimate view of heroic characters against a

highly-detailed yet sweeping background meant to illustrate the

fundamental struggle between good and evil, light and darkness. That’s

what I go to space opera for.

Look at how Altdorfer laid out the action: the incredibly-detailed

foreground that highlights the two antagonists: Alexander sweeping in

from the West (out of the Sun) at the head of his Companions, pursuing

his defeated enemy Darius on his chariot fleeing to the East (towards

the Moon), all surrounded by a swirl of cavalry and foot soldiers. All

this is portrayed in a physically impossible perspective that rises up

past the chaos of battle to portray the Mediterranean Sea, Cyprus, the

Nile, the Red Sea, and eventually encompasses three continents (Europe,

Asia, and Africa) and reveals the curvature of the earth at the horizon,

with an apocalyptic sky dominating the whole. (And if you tilted the

suspended description panel at the top of the painting back away from

the viewer…Star Wars, anyone?)

The painting is dense with symbolism and detail, ranging from

unrealistic ones like ladies in court dress at the edge of the battle,

to highly-archetypal ones like the Sun and crescent Moon. It’s a visual

feast that invites zooming in and out, one that you can return to again

and again, gaining something new each time, just like re-reading a big,

chewy space opera (or epic fantasy, for that matter: check out my

co-writer Sherwood Smith’s blog post

on that subject). And really, one need only change a few details in the

painting, add some spaceships, substitute blasters for lances, pull

back a little farther so the Earth is just one planet in an even bigger

panorama, and, voila: space opera.

Basically, I think space opera, like epic fantasy, is simply the way

most people see the world on any scale, from the personal to the grand

sweep of history: as a story with a goal, a story where every pattern,

every detail, points to deeper meaning. The dark side of this

perspective is conspiracy theory; the light side, great art.

What do you think?

In their 2003 article How Shit Became Shinola: Definition and Redefinition of Space Opera ,

David G. Hartwell and Kathryn Cramer defined modern space opera as

“colorful, dramatic, large scale science fiction adventure, competently

and sometimes beautifully written, usually focused on a sympathetic,

heroic central character, and plot action … and usually set in the

relatively distant future and in space or on other worlds,

characteristically optimistic in tone.”

It would be hard to improve on that definition using words (although I

could write an entire blog post concerning the exceptions that prove

the rule—and maybe I will one of these days), but I can show you what I

go to space opera for with a single image.

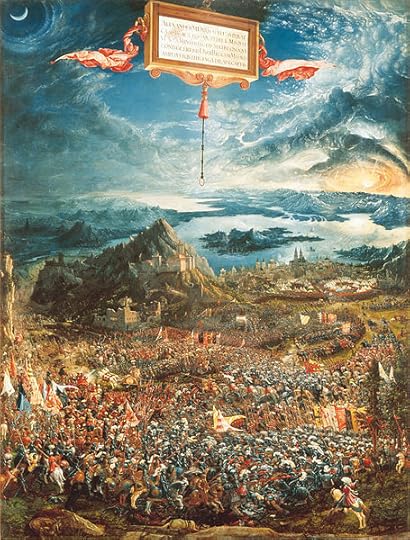

That’s the Alexanderschlacht (The Battle of Alexander at Issus)

by Albrecht Altdorfer, which was commissioned in 1528 by William IV,

Duke of Bavaria. Altdorfer’s conception of the painting was almost

certainly heavily influenced by the defeat of the Suleiman the

Magnificent at the Seige of Vienna the next year, and his execution of

the commission epitomizes what I look for in space opera, and what

Sherwood Smith and I tried to do in our space opera Exordium , which is being reissued in a revised edition by Book View Café.

Alexanderschlacht portrays the victory of Alexander over

Darius III in a battle that was the beginning of the end for the Persian

Empire, which fell in 330 BCE with the death of Darius and Alexander’s

assumption of his title as king, assuring the Hellenization of the Near

East. The work’s composition is thought to echo the four-kingdom

eschatology of the Book of Daniel—Babylon (note the distant Tower of

Babylon at the left side of the painting, under the crescent moon),

Persia, Greece, and Rome), with Alexander’s victory representing the

triumph of Greece over Persia, and echoing the hope that the relief of

Vienna represented the triumph of Christendom (i.e., Rome) over Islam.

The description of the painting in Wikipedia starts by noting the “impossible viewpoint” of the painting, but that’s precisely what the Alexanderschlacht

shares with space opera, and why it can serve as the

picture-worth-a-thousand-words definition of the genre. Rather than

“impossible viewpoint,” I’d call it the “archetypal perspective:” a

close-up and even intimate view of heroic characters against a

highly-detailed yet sweeping background meant to illustrate the

fundamental struggle between good and evil, light and darkness. That’s

what I go to space opera for.

Look at how Altdorfer laid out the action: the incredibly-detailed

foreground that highlights the two antagonists: Alexander sweeping in

from the West (out of the Sun) at the head of his Companions, pursuing

his defeated enemy Darius on his chariot fleeing to the East (towards

the Moon), all surrounded by a swirl of cavalry and foot soldiers. All

this is portrayed in a physically impossible perspective that rises up

past the chaos of battle to portray the Mediterranean Sea, Cyprus, the

Nile, the Red Sea, and eventually encompasses three continents (Europe,

Asia, and Africa) and reveals the curvature of the earth at the horizon,

with an apocalyptic sky dominating the whole. (And if you tilted the

suspended description panel at the top of the painting back away from

the viewer…Star Wars, anyone?)

The painting is dense with symbolism and detail, ranging from

unrealistic ones like ladies in court dress at the edge of the battle,

to highly-archetypal ones like the Sun and crescent Moon. It’s a visual

feast that invites zooming in and out, one that you can return to again

and again, gaining something new each time, just like re-reading a big,

chewy space opera (or epic fantasy, for that matter: check out my

co-writer Sherwood Smith’s blog post

on that subject). And really, one need only change a few details in the

painting, add some spaceships, substitute blasters for lances, pull

back a little farther so the Earth is just one planet in an even bigger

panorama, and, voila: space opera.

Basically, I think space opera, like epic fantasy, is simply the way

most people see the world on any scale, from the personal to the grand

sweep of history: as a story with a goal, a story where every pattern,

every detail, points to deeper meaning. The dark side of this

perspective is conspiracy theory; the light side, great art.

What do you think?

Published on April 12, 2013 01:00

No comments have been added yet.