Robert M. Ellis's Blog, page 4

January 8, 2013

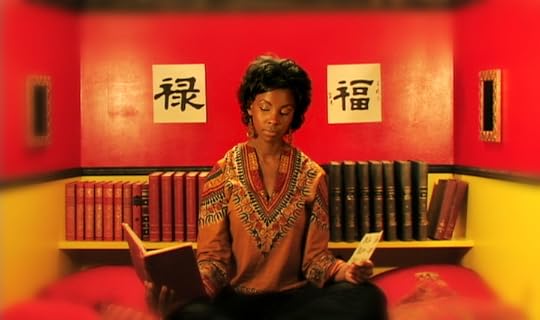

The New Chinese Room

I have just returned from a writing retreat in Ireland in which I was thinking long and hard about meaning, working on the first half of volume 3 of my ‘Middle Way Philosophy’ series. A lot of what I was doing involved synthesising various sources: the linguistic philosophy of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson, Jung’s theory of archetypes, and McGilchrist’s work on the brain hemispheres. One of the ideas that struck me was the following update of a famous thought experiment by philosopher John Searle, the Chinese Room.

In the original version of the thought experiment by Searle, an English speaker who does not understand Chinese is confined to a room with a lot of coding books, which she uses to translate one incomprehensible Chinese symbol into another. A Chinese person outside the room then passes Chinese symbols through a slot, and the English speaker then turns them into other symbols by following the instructions. The Chinese person outside thus experiences a conversation in which meaningful symbols are exchanged, but the person inside the room has no comprehension of the meaning of the conversation she is apparently engaged in.

an English speaker who does not understand Chinese is confined to a room with a lot of coding books, which she uses to translate one incomprehensible Chinese symbol into another. A Chinese person outside the room then passes Chinese symbols through a slot, and the English speaker then turns them into other symbols by following the instructions. The Chinese person outside thus experiences a conversation in which meaningful symbols are exchanged, but the person inside the room has no comprehension of the meaning of the conversation she is apparently engaged in.

In Searle’s version of the thought experiment, the person in the Chinese room represents a computer, and the thought experiment demonstrates the distinction between syntax and semantics: that symbols can be manipulated without understanding through a mechanical process so as to give the appearance of meaning, without meaning being present. Searle wanted to prove that only biological organisms, not machines, experience meaning.

However, I think that in the light of Iain McGilchrist’s work on the hemispheres, and the theory of meaning processed in the right hemisphere offered by Lakoff and Johnson, we need to revise this thought experiment. It’s not computers that are the issue, because we have constructed computers: it’s the human brain.

Let’s slightly revise the thought experiment. Let’s say that the person inside the Chinese Room is not wholly ignorant of Chinese. She’s done a beginner’s course in Mandarin a long time ago. With an enormous effort she could start to work out and dimly grasp the meaning of the characters. However, this would run entirely against her habits. She really doesn’t want to make that effort, and what’s more she finds it deeply boring to have to do so. It’s much easier just to look up the codes and do an automatic processing job: so that’s what she does most of the time, in a zombie-like state. She just wants to finish the job and get it over with. For the person on the outside, however, the Chinese characters are highly meaningful, full of freshly minted interest.

Here the person in the Chinese room represents not a computer, but the left hemisphere of the brain. The left hemisphere may not be totally incapable of meaningful understanding, but its habits run otherwise, and those habits are deeply grooved by long specialisation. Instead, it processes the meaning fed into it by the right hemisphere. For the right hemisphere, it is extremely significant. Lakoff and Johnson explain the basis of that significance: gestalt physical experiences of the body or of basic perception, extended by metaphor and metonymy. Basically, if we accept their explanation, all meaning is meaning for a person and is understood within a physical, biological context, processed by a right brain that makes fresh links between abstractions and physical experience through metaphor. The left hemisphere processes that meaning within certain cognitive models that it contributes to setting up, but it does not by itself appreciate meaning - at least as a matter of habit, perhaps not as a matter of capacity.

Then lets extend the analogy a little more. Image that the person in the Chinese Room started to construct a theory of meaning. Obviously the symbols she was processing would have their own kind of “meaning” for her, but this meaning would be based solely on the feedback given from outside the room. So perhaps she might misapply the instructions and put together symbols that did not lead to satisfactory replies, and she would start to call these ways of using symbols “meaningless”. Other ways of following the instructions that led to codes that did get satisfactory replies would be understood as “meaningful”. All the time, however, she would not really have any understanding of what the person outside the room meant by “meaningful” or “meaningless” in relation to experience. This represents the theories of meaning in analytic philosophy and linguistics, which rely only on the left hemisphere to explain meaning.

The distinction between the person outside the room and the person inside the room here is no longer that between syntax and semantics, but between two aspects of semantics: the ‘live’ and the ‘dead’: let’s call them person-semantics and zombie-semantics. Person-semantics has an immediate impact on experience, and can engage appreciatively in the arts. Zombie-semantics only deals with dead metaphors that continue to be purposefully used but are helpful only for their exchange value, not their relationship to experience.

I believe this account of meaning poses a profound challenge to the left brain dominance we are so used to: the dualism, the inability to account for objectivity without dogma, the confusion about ethics and aesthetics, the managerialism and bureaucracy. It is time the person in the Chinese Room broke out of it and started recognising the person outside, rather than pretending that her narrow confines are the whole of reality.

Picture: Dionne Dawson from the film of ‘The Chinese Room’ (Wikimedia Commons: Creative Commons licence for picture only).

December 17, 2012

Another massacre of the innocents

A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.

So says the Second Amendment to the US Constitution, passed in 1791. Once again this right is in many people’s minds both in the US and across the world, following yet another school massacre at Newtown, Connecticut: this one all the more poignant for taking place in a primary school and involving the slaughter of children as young as six, and all the more symbolic for occurring just before Christmas, which is associated with Herod’s massacre of the innocents.

What psychological process lies behind the retention of a right that had a relevant purpose in 1791 – a purpose stated in the amendment itself, and a purpose that is clearly no longer operative – a right that leads to extraordinarily high rates of death involving guns in the US, both intentional and accidental? None other, I would suggest, than those that motivate every other metaphysical claim: the identification with a representation of the world that provides both a sense of certainty and a sense of group solidarity. The original massacre of the innocents is used in Christian tradition to show God’s favour for the infant Jesus in escaping it, and give a stronger impression of an evil world in need of a redeemer. This one, though no less demonstrative of metaphysical identification, is a more direct result of absolute identification with a right that has lost its original context.

In the case of the Second Amendment, the absolute identification with a moral right enshrined in a sacred constitution is reinforced by its association with various other metaphysical beliefs. One is the belief in self defence with its associations with the absolute status of a self to be defended and the utter rejection of the ‘enemy’ to be defended against. Another is the ideological rejection of the state, and the idea that weapons can help to maintain a citizen’s independence against the state. Thirdly, there is the belief in absolute responsibility based on absolute freewill, expressed in the US conservative view that “people kill people, not guns”. Put these four bits of metaphysics together in interlinked support - an absolute right regardless of context, rigid belief in the self, ideological commitments, and metaphysical freewill – and you have a powerful combination that is difficult to shift, because even if you undermine belief in one of those four the others will make the position effectively rigid.

This is yet another example of how religion has no monopoly on metaphysical rigidity. A religion might have a similar set of interlinked metaphysical beliefs (e.g. in God, absolute revelatory ethics, freewill and cosmic justice) which would be just as hard to shift, but human patterns of belief and identification will set up these patterns of metaphysical belief in all sorts of contexts. Such patterns can occur in ‘secular’ contexts just as easily as in religious ones.

The conservatives who say that banning guns will not change the human heart are right in some ways. However, the opening up of human hearts and minds to the extent that would be required for American conservatives to let go of the Second Amendment is what would be required to produce more effective gun laws in the first place. More effective gun laws might then limit some of the effects of the extremes of the obsessive human heart, and help to create a less polarised social and political climate – not to mention saving a few innocent lives.

I’m not much given to quoting Buddhist scriptures, but a couple of verses near the beginning of the Dhammapada do keep springing to mind here. They focus on the retrospective of hatred, but could be applied just as much to the prospective of fear that inspires an arms race of self-protection.

“He abused me! He injured me! He overcame me! He deprived me!” For those who entertain such thoughts, enmity does not abate.

Enmities do not abate at any time through enmity: they abate through friendliness

Picture: Massacre of the Innocents from Tapestry in Collegiale de Notre Dame, Beaune, France: photographed by Mattana (Wikimedia Commons). Picture only freely reproducible under Creative Commons licence.

December 11, 2012

Five sorts of Secular Buddhism?

December 5, 2012

Why meaning matters

It’s getting to that time of year when in England the night seems to start in the middle of the afternoon, and everyone begins to look forward to a holiday. However, for me the prospect of the Christmas period is not one of eating large amounts of food and being bored by seldom-seen relatives. Instead it has become my custom to go off on solitary retreat and spend two weeks writing philosophy. My task for this Christmas is to get going on the third volume of my Middle Way Philosophy series – The Integration of Meaning. There seems to be little in Middle Way Philosophy that causes more bemusement than my ideas about meaning, so I thought I’d try to set down here a brief and accessible account of why I’m interested in it.

In philosophy, you could say that meaning is at the root of everything else. One’s ethics, for example, dependent on one’s epistemology (i.e. how one justifies one’s beliefs) and metaphysics – in my case critical metaphysics. In turn, though, epistemology and metaphysics depend on one’s understanding of meaning. I see the way we live our lives as being justified by our capacity to be genuinely practical and avoid the dogmas of metaphysics. The basic reason why metaphysics blocks moral progress (is evil, in effect) is that it tries to put itself beyond all possible challenge. It is the pretence of infallibility that makes it impossible for us to address conditions. However, it can only attempt to place itself beyond all possible challenge by assuming that it is possible for a claim made out of words to be beyond challenge in the first place. It can only be beyond challenge if it has some kind of hotline to truth (dealing with that is where scepticism comes in) and if it is capable of representing truth.

So, people who believe in metaphysics of one sort or another tend to think of language as having that property – of being capable of representing truth – and of the meaning of language as being equivalent to representation. Alternatively at the other extreme they might think that language expresses a purely subjective truth coming from the self, but the representational extreme is far more common. Without this assumption that meaning is representation – or its opposite – metaphysics would be impossible to sustain coherently. Yet representationalism or its opposite are virtually universal in Western society amongst those who have ever thought about the subject. Representationalism is entrenched in analytic philosophy, implicitly assumed by scientists and many others, and its opposite is only found in cultural studies and postmodernism. Is it any wonder that we keep falling unawares into metaphysical ways of thinking, if our understanding of the very language we are using constantly creates the ready conditions to push us in that direction?

Yet how do we find a Middle Way in our understanding of meaning? My suggestion is that we do not deny either that meaning can involve either a relationship to our picture of the world, or an expression of our feelings about it. We have to hold both of these aspects of meaning in synthesis, difficult though this may seem. Meaning is not merely representation potentially relating to the world in propositions, nor is it merely the expression of feelings about the world – which might come in single words, music, or grunts. Instead, it is both in varying proportions. Instead, we have to constantly avoid the egoistic assumption that we have understood the whole meaning of anything – of a symbol, word, proposition, person, country, or whatever. We cannot claim to have exhausted the whole of any meaning merely by understanding what we think it represents or expresses, for there is always more. Representation links to a whole implied world, and expression to a whole sphere of meaning, which we can understand increasingly but never as a whole. We integrate meaning by bringing together those scraps of representation or expression that we recognise as no longer telling the whole story, merely contributing to it.

So, I think that discussion of meaning is a crucial, but neglected, element of Middle Way Philosophy. It is perhaps easier to understand why rigid beliefs are problematic: we expect beliefs to shape our attitudes. We also expect desires to be troublesome, whether we encounter these in the context of addiction, therapy or guilt. However, meaning plays a crucial intermediary role in transmitting belief and desire to each other. Rigidity of meaning, where we do not understand what another person is talking about, or where we are not prepared to engage with language in new ways, lays down the groundwork for rigidity of belief, and is in many ways harder to shake. How can you incorporate a new concept into your beliefs about the world if you don’t understand it in the first place? The practice of integrating meaning also offers a central role for the arts, which in this way become no longer marginal to a coherent moral understanding.

The integration of meaning to me seems to demand a completely open kind of generosity, an allowance of profusion, which we cannot safely apply to our beliefs. In imagining this I am indebted to an idea of John Heron, who talks of (what I would call) meaning as being allowed to grow freely like his beard, whilst what I would call belief is subject to a sceptical razor. Our beliefs need to be constantly kept in some kind of balanced control, checked against evidence. Meaning, however, is free, the more the better. Any story you may come across, no matter how far-fetched in scientific terms, offers meaning, and may add to your appreciation of what is meaningful. The beard may grow as straggly and unruly as we wish, and, as long as we do not confuse meaning with belief (often described as ‘taking things literally’) that is all to the good. That, for example, is why I find the Bible and Qur’an fascinating documents, whilst rejecting the revelatory claims often associated with them. Both are rich in meaning. Perhaps this artistic attitude is somewhere near the base of my whole attitude to Middle Way Philosophy, and stops scepticism becoming a pinched puritanical reflex. Long may meaning grow!

Links to related pages:

Jung and the meaning of God (blog post)

Meaning (concept glossary page)

Integration and meaning (from ’A Theory of Moral Objectivity’)

Picture: Townsend-Harris (public domain)