Robert M. Ellis's Blog, page 3

June 4, 2013

Better Angels

A review of ‘The Better Angels of our Nature’ by Steven Pinker – Amazon link

The facts seem clear. Our lives are enormously safer than they used to be. Compared to prehistoric or medieval times the violence in modern society is a tiny proportion, and even in the past generation the overall violence created by both war and crime continues to reduce significantly. Looked at in terms of the bigger picture, even the Second World War was a blip that only temporarily interrupted a larger improving pattern. We are doing something right.

The facts seem clear. Our lives are enormously safer than they used to be. Compared to prehistoric or medieval times the violence in modern society is a tiny proportion, and even in the past generation the overall violence created by both war and crime continues to reduce significantly. Looked at in terms of the bigger picture, even the Second World War was a blip that only temporarily interrupted a larger improving pattern. We are doing something right.

Steven Pinker’s detailed and well-evidenced book provides this important optimistic message – that the levels of violence in the world are decreasing – and more importantly gives a convincing account as to why. Weighing in at over 1000 pages, it is almost encyclopedic in its coverage of evidence about all aspects of violence through history. However, Pinker doesn’t just provide lots of evidence, but also a series of counter-arguments against stock explanations and a strong account of the endogenous causes (i.e. ones that are distinct from the phenomena being explained).

So why is violence decreasing? Pinker’s final chapter usefully summarises five big picture trends. First there was the nation state, that drastically reduced violence by providing a neutral arbiter to maintain order. Next there was increasing commerce, which from the late middle ages has provided an alternative way of competing in which we have a positive investment in the lives and prosperity of others. Then there is feminisation: the more women have improved their status in society, the more peaceful it has generally become. Then there is the extension of sympathy, for which we have much to thank the novel and other media, and finally the escalator of reason, by which we have gradually improved the consistency with which we treat others, thanks particularly to mass education and the gradual percolation of rational attitudes through our society.

What made me initially interested in this book, and its connection with Middle Way Philosophy, was the amount it tells us about conflict. Conflict is a central theme of my recent book, Middle Way Philosophy 2: The Integration of Desire, where I put forward a view of conflict as created by our divided selves as much as differences between persons. In that book there is relatively little attention to violence specifically, but I describe violence as disinhibited conflict. This is a long way from Pinker’s approach, as he focuses solely on identifiable social and psychological causes of violence between people, and does not really make any distinction between violence and conflict. He gives no attention at all to inner conflict, or violence against oneself when that conflict becomes disinhibited. Nevertheless, I have learnt much from what he has shown within the model he was using, because much of what he says about the causes of violence or its decrease also explains the causes of conflict.

Of the five kinds of causes for improvement that Pinker discusses, mentioned above, the first three seem to me to be largely focused on violence rather than conflict. The development of the state, for example, inhibits people from settling their disputes violently, because they are increasingly afraid of punishment by the state, but it does not by itself resolve conflicts between people. Rather, under the threat of the law, people become more likely to repress the contrary desires that created external conflict. If instead of attacking my enemy, I repress my anger, I will substitute an internal conflict for an external one. This is indeed progress – but progress in reducing violence rather than progress in reducing conflict. Similar points can be made about the effects of commerce, because the reflection that violence would interfere with business interests is more likely to repress emotions that would previously have produced violence than to make them disappear.

When we come to the improved position of women in society, however, there does seem to be some genuine resolution of conflict together with mere repression of desires. Women, at least, probably have to repress desires less, and face less inner conflict thanks to their liberation, even if there are men who repress them more compared to their previous position. Feminisation appears to be partially about reducing violence and partially about reducing conflict.

However, Pinker’s last two and most recent factors, the expanding circle of sympathy and escalator of reason, potentially indicate a lot more genuine resolution of conflict, with a reduction of violence following from this rather than violence merely being inhibited. When we actually come to feel that others are like ourselves, or to think of them as having similar status, we are actually being more objective and addressing more conditions. Pinker makes it clear here how much we have improved since the Enlightenment: slavery, the treating of women and children as chattels, and wanton cruelty to animals have all successively been drastically reduced as an increasing range of others were recognised as persons and considered fit subjects of moral and legal rights. This has been accompanied by the rise of democracy and the use of peaceful political methods for the resolution of disputes both within and between nations. Pinker gives a huge amount of evidence for this on a social level, but what he does not seem to recognise is its internal psychological benefits: for every avoidance of conflict through the objective recognition of others is simultaneously an avoidance of the repression and alienation that would follow from our repressed sympathies and divided reason. The recent achievements of Western civilisation in reducing violence are simultaneously achievements of greater integration.

Many will find that point difficult to stomach, accustomed as we may be now to dwell particularly on the environmental shortcomings of our civilisation, as well as its many other serious imperfections. But Pinker stands up for the sheer imperfect inductive power of evidence. The evidence builds up and can hardly be dismissed without prejudice. We may still have a long way to go, but our civilisation has made massive gains in objectivity. If we do not allow ourselves to appreciate this we will probably be imposing some dogma of pessimism rather than looking at the evidence. So we do not need to idealise the East, or the Past, or some alternative ‘natural’ or revealed way of understanding things apart from the accumulating evidence of experience. We just need to have confidence in what we have done and build on it. The importance of Pinker’s book as a healthy basis for optimism can hardly be understated.

May 12, 2013

Virtual Sixth Form College

Only five months ago, the idea of a virtual sixth form college was one of many found only in my head. Now the whole project is making headway. There is a group of us working on it, and more than a hundred supporters subscribing to our updates. Things have moved exhilaratingly fast of late, and for me it marks an important transition from theory to practice – practice not just at a personal but at a social level.

As regards the project itself, I will be brief here. The idea is to offer state-funded A Level courses (equivalent to senior high school for Americans) to students in their own homes. Virtual schools are nothing new, and even publicly-funded virtual schools exist in the US, but such schools seem to make little use of video conferencing, which can help make much more supportive connections between teacher and student, and they also don’t seem to be much focused on the 16-19 age group, that is more independent than younger students and thus better able to cope with distance learning. Since I have specialised in teaching 16-19 year olds most of my career, I want to offer a new option for this kind of education that incorporates some of the flexibility of virtual learning from home, but also offers the much higher levels of teaching support and range of specialised A Level courses to be found in a sixth form college. For more about the project, see our website, http://www.vsfc.org.uk .

What does this project have to do with Middle Way Philosophy? Well, nothing formal. I’m certainly not expecting those involved to necessarily take any interest in it, or to necessarily agree with my specific philosophical perspectives. There are already a variety of people involved with a great variety of backgrounds and motives, which is exactly what I would hope. However, it will also be obvious that both Middle Way Philosophy (in the form I have been writing about it) and the Virtual Sixth Form College are my brainchildren, which makes them siblings. There are likely to be various traceable family resemblances. Any educational institution also needs an ‘educational philosophy’ or a ‘vision’ that binds it together.

For me the crucial connecting idea is that of addressing conditions, and of holding the need to do this in balance with ideals. In education ideals often get tediously over-repeated, in the form of educational mission statements, school mottos, or political rallying cries. Every school wants academic excellence and to help their students to develop, so to merely repeat this tells us little. But these ideals will not mean very much unless they are engaged with the conditions created by a particular set of students. Students have varying needs, some of which will probably be best addressed by the conventional education in a school or college currently available. Others, however, might prefer and benefit more from learning virtually at home for a variety of reasons. For example they may be introverts (see previous post Quiet up!), have more specific issues such as school phobia or Asperger’s, live in a remote place, or want to study specialised A Level subjects not available locally.

The insight of the Middle Way applied to education is just that the need to address conditions is itself part of the ideal. We need to avoid rigid metaphysical views either way: either just the assertion of ideals with the insistence that students should be made to fit these ideals, or on the other hand too much acceptance of the current habits of students and a failure to challenge them. We need accept neither the dogmatic freewill belief that claims ‘students just need to make more effort’, nor the dogmatic determinist belief that they are not really capable of developing beyond the frame set up by their background.

I see virtual education as just the part of this balancing that I happen to be involved in. It can provide new opportunities for some students to find the right balance by being educated at more of a remove from an institutional atmosphere. It’s not going to fit the needs of every student, and we shouldn;t make exaggerated claims for it. But virtual education offers exciting new possibilities if we use them wisely.

April 12, 2013

Religion is not just for atheists

I picked up Alain de Botton’s recent book Religion for Atheists with a certain amount of curiosity, though not with very high expectations. In some ways it exceeds those expectations, and in others my misgivings are confirmed. I am glad that this kind of thinking is going on, and de Botton does it with creativity and pizazz, but his reflections are not subjected to even a basic level of critical scrutiny. Is this ‘philosophy’? Of a kind, yes, and it may be more valuable than much else that passes under that heading (I value creativity more than misdirected rigour), but if there was just a bit more critical thinking too it would be much more fully worthy of the name. Nor would a bit more selective rigour in the right places necessarily have to alienate the popular audience he wants to engage.

with a certain amount of curiosity, though not with very high expectations. In some ways it exceeds those expectations, and in others my misgivings are confirmed. I am glad that this kind of thinking is going on, and de Botton does it with creativity and pizazz, but his reflections are not subjected to even a basic level of critical scrutiny. Is this ‘philosophy’? Of a kind, yes, and it may be more valuable than much else that passes under that heading (I value creativity more than misdirected rigour), but if there was just a bit more critical thinking too it would be much more fully worthy of the name. Nor would a bit more selective rigour in the right places necessarily have to alienate the popular audience he wants to engage.

The overall idea for the project is an excellent one: to examine the positive role of religion in human experience, and make suggestions for how that positive role could be reproduced outside a formal religious context in a way that doesn’t require supernatural beliefs. It’s a valuable dialectical project, bringing together aspects of experience that are too often falsely opposed. I also admire de Botton’s unapologetic eclecticism and use of his own experience (which seems to be particularly of Judaism and Catholicism) in taking and adapting ideas from religion. It’s also (in a very broad sense), a psychologically-based book in that de Botton is interested in extracting the positive psychological functions from religious objects or practices. He believes that religion can help us to address human weaknesses, and in that sense this is also a moral book.

However, by far the most striking and interesting aspect of the book is the creative suggestions for new secular practices that would reproduce functions currently limited to religion and generally lacking in secular society. These suggestions often seem like just brainstorming (they are not exactly thought out in practice or turned into detailed proposals), but they are nevertheless intriguing, and engagingly presented with illustrations. For example, there is the Agape restaurant where people could meet strangers and create community by having structured conversations that make people engage emotionally with each other – as opposed to creating a fake private enclave for the small group you came in with, as in most restaurants. De Botton wants advertising for virtues rather than products, a quarterly day of atonement for all, the restructuring of university study and of the presentation of art so as to reflect people’s psychological needs, the building of secular temples, and the creation of secular ‘religious’ institutions rather than just the publishing of books. Many of these proposals sound great, but many are also a little impractical. Approaches like the re-classification of art collections in psychological categories, though, have already been done to some extent, and all that is needed for an Agape Restaurant is for an entrepreneur to set one up (I’d certainly go!).

But then we come to the many limitations of this book. The first and most glaring one is the title. Like many current so-called atheists, his justifications for atheism (which he scarcely discusses at all) are ones that support only hard agnosticism rather than atheism. De Botton starts off by saying “The most boring and unproductive question one can ask of any religion is whether or not it is true“. I thoroughly agree with him there. Why, then, does he adopt a position normally associated with the belief that it is untrue, rather than systematically disengaging himself from this unproductive question? Like most so-called atheists, he recognises that supernatural claims cannot be shown or even evidenced to be either true or false, and yet still take this as a basis for believing that religion is false. In de Botton’s case, this seems to be a matter of the uncritical adoption of his family heritage, as he was brought up in “a committedly atheistic household” and, he says “I never wavered in my certainty that God did not exist”. He appears, in fact, to be a merely ethnic atheist, in the same way that one can be an ethnic Christian, Muslim etc who accept these beliefs for merely traditional reasons.

In this way, too, he reflects what seems to be an increasing modern tendency to try to appropriate the doubtful centre ground to an atheist or secularist perspective. At other times, he does the reverse and appropriates the centre ground to what he takes to be a useful but traditional religious perspective, such as religious pessimism about human perfection in this life, or religious transcendence as a way of offering a wider perspective from our limited everyday assumptions. In both these cases, he is using the religious perspective just as a counter-balance. I think he’s right to criticise the modern secular worldview for shallow optimism, but the sustainable antidote to shallow optimism is not pessimism but a balanced perspective. Similarly the best antidote to an over-narrow perspective is a broader one that balances experience with aspiration, not, as de Botton seems to think, an absolute transcendent alternative beyond experience.

De Botton’s objections to religion appear to have very shallow roots. They amount to a disinclination to believe in supernatural claims, and there appears to be no understanding of the much more far-reaching and important moral and psychological criticisms that can be made of many religious approaches. For example, much religious handling of ethics is totally ineffective because it just consists in preaching and moral instruction, requiring adherence to often unrealistic sets of rules, from which people then become alienated. This religious tendency can be directly related to the religious understanding of the sources of ethics in transcendent authority such as God or enlightened beings, so alienation springs from the appeal to authority which springs from metaphysics. De Botton, on the other hand, seems to think that religious ethics are fine as they are, and that in fact that we need more ineffective sermonising in the modern world. But if metaphysical beliefs had no negative psychological or moral effects, as he seems to assume, they would be entirely harmless and we could adopt them pragmatically without concern. Like many traditional religious believers, de Botton seems to think that the main problem of ethics is ‘weakness of will’, assuming that we are just one single self that can’t keep up its commitments because of forgetfulness. But the problem of moral objectivity is far more profound, and more soluble, than this, because we experience many apparent conflicting selves. Just to recruit one of those selves to the cause of ‘the good’ by preaching to it (leaving the rest untouched or opposing) achieves very little without integration of those conflicting elements within us.

De Botton’s view of ethics, in fact, seems to be just a reduction to social needs and communal adaptation. Not only is this incredibly simplistic as an account of ethics, but it does no justice to what is positive in the religious account of ethics. It makes ethics relativist, so that we have no grounds for ethical assessment of others’ conduct, and it makes ethics irrelevant to solitary experience. If religion has anything valuable to teach, surely, it is in the solitary experience of mystics, whose moral struggles had nothing to do with fulfilling social needs, but can easily be understood nevertheless without appeal to God in terms of integration of the psyche. De Botton completely ignores the religious elements of solitary experience.

De Botton also seems to take the mere expression of religious emotion to be an end in itself. He gives moving examples such as that of a despairing middle-aged man seeking solace in a church (p.166). The message is that religion can offer consolation to people in this kind of condition, and the secular world should take seriously the importance of providing such consolations and enable them to be provided in other ways. But de Botton pays no heed to the wider context of such episodes. Surely the man is seeking solace here from an object that cannot provide it, except in a cyclical, self-feeding fashion, rather like that of a drug? For a longer-term solution to his state of mind the man certainly needs acknowledgement of his emotions, but he also needs goals that lie beyond them and a strategy for weaning himself off dependency on self-feeding depressive tendencies. An icon of the Virgin Mary (or its secular equivalent) can scarcely provide this.

So, whilst de Botton’s book is full of creative ideas, it is scarcely coherent, not at all self-critical, and contains little by way of thinking about the underlying problems involved in taking the best from religious traditions and adapting them to secular society. For this we need above all a new vision of ethics and well-articulated integrative psychology: but de Botton offers neither of these, merely recycling old ineffective religious solutions in a superficially secular guise. He owes his increasing and expectant popular readership a bit more than this.

Finally, we could also come back to the title of the book and note that the kind of reformed ‘religion’ he offers is not just for atheists at all. As I have already noted, it is primarily for agnostics (and in practice, agnostics may be more open to it than atheists are). However, given how little he has actually modified religious approaches, they could also well be used by old-fashioned believers who want to spruce up their marketing ideas a bit. This would be a perfectly good handbook of ideas for an evangelical Christian, for example, as evangelical Christians are constantly looking for new ways of engaging people in religious approaches. Re-arranged art galleries, Agape restaurants and virtuous advertising might be just the thing for a bit of fresh evangelism. Despite its many attractions, then, this really is about the most mis-named book I have ever read.

March 31, 2013

Silence

But hark to the suspiration, the uninterrupted news that grows out of silence.

(Rainer Maria Rilke: Duino Elegy 1)

I have just been thinking about the role of silence, after reading a review of a new book by Diarmid McCulloch on Silence in Christianity. There are two types of silence: the absence of communication and the absence of ‘mental chatter’ or left brain activity. I am interested here in the second. The mere absence of communication may cover up a huge amount of obsessive thinking, suspicion, or other negative emotions. We can read what we wish into someone else’s silence (although there are often lots of contextual clues). The second type of silence, however, marks a temporary change in mental states and attitudes.

Silence of this kind is very basic: we become watchful and receptive rather than trying to manipulate the world in any way. We switch from a mode in which the left hemisphere of the brain is dominant to one where the right hemisphere gets its turn. The extent to which the right hemisphere really takes over depends on how deep that silence is. It might just be a momentary pause for re-balancing, after which the left hemisphere takes over again. A deeper silence, though, can be developed in successful meditation practice, or indeed in any other receptive activity: really listening to a piece of music, for example.

Diarmid McCulloch points out the importance of silence in the history of Christianity from the beginning. When Jesus was before Pontius Pilate, his response to some of the accusations was silence rather than an attempt to defend himself. Perhaps we could read into this a recognition that further justificatory words from the left hemisphere would merely entrench the existing conflict. The same point applies to the ‘silence’ of the Buddha, when asked questions about metaphysical truths beyond experience. Recognising that any possible answer would merely entrench left-brain responses in a way that completely excluded any consultation with experience through the right brain, he could only point to the openness of the right brain by remaining silent. Just referring to the right brain in language (as I am doing now), does have the merit of the left brain recognising its own limitations, but it doesn’t necessarily do the job, as it is always possible to come up with some kind of rationalised objection if you stick only in the terms of the left brain.

The skilful use of silence thus seems to be an important part of following the Middle Way, for it enables greater integration between left and right brain functions. It’s not an aspect of the Middle Way I am particularly good at myself. I have a tendency to go on arguing beyond the point where many others have given up because they recognise the debate as useless. My left brain also has a tendency to enter periods of hyper-activity, one of which I have been in recently, where I am ceaselessly involved in plans and analysis. However, I do recognise that it is important to be able to get out of this state and develop a wider perspective. Tomorrow I set off for a holiday – a week’s walking on the Welsh coast – which I hope will cool down my habitually over-heated left hemisphere and get me a bit more in touch with silence, through the medium of physical activity.

The theme of silence also has a relationship to my previous review on this blog of the book ‘Quiet’. It tends to be introverts who appreciate the value of silence more than extroverts, and who are constitutionally more likely to fall into a watchful rather than a manipulative mode. But of course, that doesn’t mean that extroverts can’t be quiet too, and the categorisation of introvert/extrovert masks an incremental gradation of degrees of appreciation of silence. One of the complaints Susan Cain makes which I would support is the dominance of society by extroverts, and this is reflected in the lack of appreciation of the value and function of silence. The ceaseless blather of background radio noise in some shops and other public places is one thing that introverts such as myself tend to hate. The assumption that silence in a context such as a classroom or an interview implies lack of confidence rather thoughtfulness is another problematic assumption of the extrovert-driven society. Even religion – unless you join in silent prayer, meditation or Quaker meetings – tends to be dominated by babble. We need a public recognition of the value of silence, starting in education and going on in other public contexts.

For the moment, though, I’m going to spend time with the crashing waves, the roaring wind on the cliffs and the cries of sea birds.

Picture: Winter Silence by Laszlo Mednyanszky (public domain)

March 12, 2013

Waiting for the Barbarians

‘Waiting for the Barbarians’ was first written by J.M. Coetzee in 1980, but it is only in recent years that I have started to read Coetzee. Most of Coetzee’s books that I have read so far are searingly honest explorations of self-identity, but this earlier book is quite different. Often described as an ‘allegory’, it has the universality of fantasy, being about nowhere and everywhere. It is set in an isolated town on the frontier of a nameless empire, and narrated by the town’s magistrate, an ageing paternalistic intellectual whose loyalty and moral ‘decency’ is tested by the arrival of ruthless inquisitors from the capital. These utilitarian militarists have a mission to destroy a ‘barbarian uprising’ which, to the extent that it ever exists, is apparently created by their over-confident fear and wilful ignorance.

‘Waiting for the Barbarians’ was first written by J.M. Coetzee in 1980, but it is only in recent years that I have started to read Coetzee. Most of Coetzee’s books that I have read so far are searingly honest explorations of self-identity, but this earlier book is quite different. Often described as an ‘allegory’, it has the universality of fantasy, being about nowhere and everywhere. It is set in an isolated town on the frontier of a nameless empire, and narrated by the town’s magistrate, an ageing paternalistic intellectual whose loyalty and moral ‘decency’ is tested by the arrival of ruthless inquisitors from the capital. These utilitarian militarists have a mission to destroy a ‘barbarian uprising’ which, to the extent that it ever exists, is apparently created by their over-confident fear and wilful ignorance.

Like torturers the world over, these people create the very conspiracies they discover. Like many a well-organised civilisation, they are bogged down, harried, and defeated by native peoples able to melt in and out of the wildlands, their highly-trained legions useless against an enemy that has barely confirmed its existence, let alone met their enemies in battle. At the end of the book, the imperial troops have left, and the magistrate, finally restored to the position he lost due to opposing the hopeless war, is left again waiting for the barbarians. It only seems to be he that has the insight to recognise that they will never come, these barbarians – except to the extent that they are already here.

I don’t think this book is an allegory, because it is not a cloaked account of the Apartheid regime in South Africa or any other specific government. Rather it is a fable that applies to all governments, and more basically, to all egos. By trying to exterminate the Shadow, we strengthen it, both within and beyond ourselves. We all have our frontier towns, and our deserts filled with hidden barbarians. Coetzee’s genius here is not just to recognise and depict this psychological situation, but to avoid setting up an idealised hero in opposition to it. Our nameless magistrate is decent rather than heroic, flawed by dithering and sexual weaknesses, and having no defence against torture beyond his recognition of its self-defeating nature. He is not able to prevent the idiotic excesses of the imperial ego, because he is part of that same empire himself and never denies his role in it. However, like realistic heroes in actual experience, he has insights that place him in some ways outside the crowd, that leave him with little choice but to try to oppose it as best he can.

Though it is already thirty years old, this book has a universal quality that will make it still relevant for millenia. It also has a profound moral quality that, like George Eliot’s, emerges gently from the limitations of the characters that exemplify it. In many ways it is a profound meditation on doubt and confidence, on the metaphysical dogmas of the imperium and the dilemmas of the insightful individual able to stand back from the group.

March 2, 2013

Quiet up!

I’ve just finished reading Susan Cain’s book Quiet, which is deservedly popular, personally engaging, and full of interesting links to Middle Way Philosophy. It is a book about introversion which points out the way that Western (especially American) culture is especially dominated by extroversion. It also points out the value of introverted traits, and the ways that introverts and extroverts are mutually dependent.

As an introvert myself, I found the book a rich source of greater understanding of the psychological processes I have gone through. She discusses the need to recognise how one is conditioned as introvert (which can be related to genetically high levels of reactivity), and the centrality of that acceptance. She points out, as I have always thought, that introversion has nothing to do with sociability in general, only with a preference for fewer deeper relationships rather than many shallow ones, and with a tendency to be fatigued by over-stimulation. However, she also explains the degree of flexibility that can attend introverted traits, and that it is quite possible to develop the capacity for extroverted behaviour in specific contexts, and to sustain that greater range, provided that one remembers the more basic need to recharge in quiet. This fits my own experience: after a little practice I have no trouble with lecturing to large audiences, for example, though public speaking is a classic stumbling-block for many introverts. Quiet is a heartening book to read if you are an introvert, and I would recommend it.

Cain’s deliberately broad definition of ‘introvert’ is bound to cause trouble with the pedantically inclined. However, she makes it clear that she includes within introversion traits that psychologists have also called conscientiousness, sensitivity, and openness to experience. She recognises how much introverts and extroverts vary, of course, but nevertheless there are justifiable generalisations to make, which are also a matter of degree. These traits often do correlate, but obviously not always: one could be a sensitive and conscientious extrovert or a dogmatic introvert. The generalisations are rough, but not so rough as to be uninformative, provided one is aware of their limitations.

Beyond my personal engagement with this book and an interest in personality psychology in its own terms, however, I also found this book exciting in relation to the questions it raised for me as to how introversion and extroversion as traits may correlate with other tendencies that I have written about. Chief amongst these are dogmatism as opposed to provisionality, the relationship of groups to metaphysical belief and individuality to openness of experience, and the dominance of the left brain over the right. The relationship between these entities is doubtless complex, but well worth disentangling, and does seem to have some crucial correlations. One central aspect of introversion as Cain depicts it is cautious awareness and observation of one’s environment before leaping into action: a trait that relates strongly to the use of the right brain rather than the left. Over-confidence about one’s environment and fixation with goals, however, is very much associated with the dominance of the left brain and the tendency of extroverts to jump unreflectively into communication. The fact that extroverts are much happier in groups seems thus less about liking people as such, than adherence to the certainties offered by the beliefs reinforced by groups – particularly metaphysical beliefs that are so well suited to the purposes of maintaining group identity. The fact that introverts cultivate individuality is what gives them access to greater creativity and insight, and the ability to examine beliefs with greater provisionality.

Surely, then, it is no coincidence that the world so much over-values extroversion, just as it is dominated by left brains. It is the smooth talkers who get through job interviews and earn bonuses, the shallow speechifiers who get elected and run most of our institutions: but these are the very people who are least well-adapted to doing so, because they have too little insight into the world around them, and are more likely to work on the basis of maladapted fixed group beliefs. It is only when introverts get lucky in an extroverted world that we get any recognition – say as scientists, writers or artists. In some ways these may be the unacknowledged legislators of the universe: but only when the extroverts bother to step aside even slightly to let them have a little influence.

Plato, who thought that the world should be run by philosophers, was right in a sense: not because of the rationality of philosophers specifically, though, but because of the dominant psychology of the thoughtful types he regarded as philosophers in his time. It is not just philosopher kings we need, but artist kings and contemplator kings: it is awareness of conditions that we need most, whether mediated by thought or feeling, sense or intuition. Why is academia so bankrupt of creativity? Because extroverts can network better and get most of the academic posts and grants. Why do we have a financial crisis? Because the financial system is overwhelmingly dominated by risk-taking extroverts. Why is life so difficult for introverted teachers and thus for introverted students? Not because introverted teachers can’t teach, but because the idea of successful teaching is so much cast in extrovert terms, and educational managers tend to impose it in those terms.

These problems are not going to go away any time soon, but the condition for them doing so is (a) the introverts having the confidence in their own value to come forward in the way Cain recommends, (b) the extroverts recognising their limitations and altering society in ways that limit their dominance. Just as the left brain needs the right to alert it to conditions, society needs introverts. Introverts have nothing to lose but the chains in which the extroverts have bound them.

February 23, 2013

Now published: The Integration of Desire

The second volume of the Middle Way Philosophy series, The Integration of Desire, is now published. Click here for more details and to purchase. An ebook will also be available soon. Also see my previous blog post on this book.

The second volume of the Middle Way Philosophy series, The Integration of Desire, is now published. Click here for more details and to purchase. An ebook will also be available soon. Also see my previous blog post on this book.

We like to think of ourselves as single selves, but when we examine our experience, it is full of conflicts of desire. One minute we want one thing, and the next something else – perhaps something completely contradictory. I may want to eat fatty or sugary food one minute, and lose weight the next; or I might want to concentrate on meditation one minute, and think about something else the next. This conflict is a microcosm of the conflicts in society between groups or even nations. We often mistakenly think of people, groups, or nations as conflicting, but this book argues that it is desires that conflict, and it is desires that need integrating.

To integrate desires, we don’t succeed just by eliminating or repressing the desire we don’t want at the moment – it’s not as easy as that. Instead, we need to bring the energies of these desires and allow them to work together. This book brings together ideas from Buddhism, philosophy, psychology and politics on how to integrate rather than repress desires. It also sees this process as morally important and constitutive of objectivity – not just a matter of therapy or compromise.

February 17, 2013

Faith and confidence

I’ve made a new blog post on the Secular Buddhism UK site on faith and confidence: see http://secularbuddhism.co.uk/2013/02/faith-and-confidence/

February 10, 2013

Aggravating aggregates

In traditional Buddhism, the 5 skandhas or ‘aggregates’ are a common way of analysing the limitations of our view of self, but I have been reminded again recently of the ways that I find them unhelpful and indeed counter-productive. The reminder came from reading Francisco Varela – a writer who is interesting in many other ways, and that I hope to write more about on another occasion. But even someone like Varela, who uses Buddhist approaches in a thoroughgoing way as they relate to cognitive science, without any obvious traditionalism, seems to have merely taken the five aggregates as Buddhism traditionally teaches them without asking the underlying questions that need to be asked about their usefulness.

The traditional Buddhist account (e.g. Majjhima Nikaya 109) tells us that the self is illusory, and that there are five aggregates that are the object of clinging, with which we might identify the self. These are form (i.e. the body), sensation, perception, volitional formations and consciousness. We might think that the body is the self, but the body is always changing and not completely identified with. We might identify with particular sensations or perceptions (perceptions also involving the identification with pleasant, painful or neutral things), but these are ever-changing. We might identify with our choices and their effects, but these are also impermanent. We might identidy with consciousness, but this is also impermanent. None of these are essentially ‘me’. Nor is there an essential ‘me’ beyond these five aggregates.

So far so good, you might think. We have deconstructed a metaphysical construct, showing how something that was assumed to “exist” and was thus the basis of dogma is not so. But the assumptions that shape the whole discussion have not been moved on by any such analysis. The underlying problematic assumption is that metaphysical claims are of any use to us at all. How does it help us to believe, for example, that I am not form, any more than it helps me to believe that I am essentially form? If I disbelieve in form it leads to idealist dogma, and if I believe in it, it leads to materialist dogma.

It is this kind of reflection that doubtless leads to the more thoughtful Buddhist writers and commentators adding here that the aggregates do not deny the existence of self, but rather try to help us let go of our clinging to self. Its goal is not to lead us to form a new belief in the non-existence of the self. But this is usually, at best, an afterthought which follows the usual exposition of the five aggregates, when for the five aggregates to be any use at all to anyone it needs to precede them. It doesn’t help us to reflect that we are not form, not sensation, not perception, or whatever, unless we are also simultaneously, just as strongly, reflecting that we are not denying these things either. Even then there is a danger that we will just be left with a kind of baffling metaphysics of emptiness, rather than shifting the way of thinking into a more useful non-metaphysical path. Even the balanced metaphysical perplexity of Nagarjuna doesn’t help us very much, because it is still all tackled at a metaphysical level and leads us to assume that that is what is relevant. It’s like telling a child to stop doing something rather than providing a distraction. If we are only told not to be metaphysical, when even this instruction is an afterthought, and when no clear alternatives are offered, it’s not at all surprising that the minute our attention lapses it goes straight back into metaphysical ways of operating.

There is an alternative. We need to accept incremental and provisional ways of talking about objects, and attempt to steer our ways of talking about them into channels that will integrate our understanding and our practice and address conditions better. If we apply that approach to the self, we have to admit that we do have an incremental and provisional self – an ego that wants to exist, and can imprint its identifications on our experience to varying extents. If anything, rather than denying that ego, we need to stretch and expand it, in the sense of integrating different desires and beliefs.

The aggregates are often taken to be a good place to start in thinking about the self in traditional Buddhism, but I think this is wrong. They are not a good place to start, because they are only possibly of any use when interpreted in terms of the Middle Way and combined with a positive alternative view of the self that is dynamic and incremental, like that offered by Jung. Without this they are positively regressive and misleading. This is one of many examples, along with those I discuss in my book The Trouble with Buddhism of the ways that traditional Buddhism possesses insights that it presents in an unhelpful way, because it has not given clear priority to the Middle Way over other ways of interpreting Buddhist teachings.

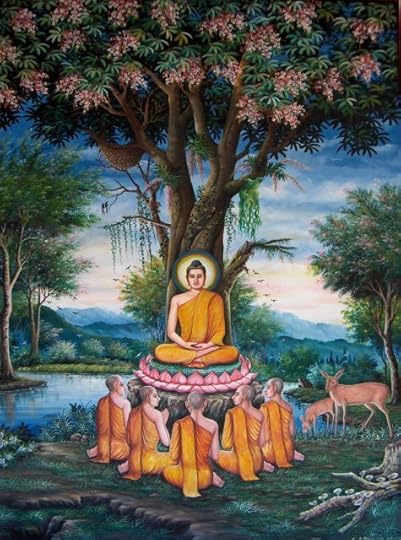

Picture: Sermon in the Deer Park from Wat Chedi Liem, taken by KayEss (Wikimedia Commons). Picture can be re-used under Creative Commons licence.

January 25, 2013

McGilchrist revisited

It’s now a little over a year since I first read ‘The Master and his Emissary’ by Iain McGilchrist. My estimation of its importance has continued to grow during that time. When I first read it I wrote a detailed review, incorporated aspects of it into my own thinking and writing, contacted the author and had the privilege of meeting him. Now I am even more convinced than ever, not that McGilchrist’s work is perfect or even that he himself understands all of its implications, but merely that those implications are profound and important.

Below is a video which contains an animation of some of McGilchrist’s key ideas about the brain. I think that it was seeing this video that first led me to read the book, so I hope it does the same for you.

What McGilchrist offers, to put it as succinctly as possible, is external scientific evidence for the epistemological and moral importance of the Middle Way. In the video above, it is his idea of “a certain necessary distance” that captures it. The left brain is obsessive, myopic and rigid,and needs the right brain to give a wider perspective on its beliefs and maintain a degree of openness and provisionality. The Middle Way is an epistemological and moral optimisation created by linking the hemispheres sufficiently to maintain that “necessary distance” and not be sucked into the assumption that the left brain’s representations are perfect. The left brain left to itself flattens and absolutises all beliefs into metaphysics, but the right sufficiently linked with the left can help provide a perspective that keeps all our theories provisional and helps us respond to conditions better. The Middle Way is thus another way of talking about the effective integration of the hemispheres.

Some people need to get over the idea that any reference to the brain is reductive. McGilchrist is the very opposite of reductive, but rather gives us a richer and fuller perspective. All the things he says about the brain can also be said just on the basis of experience without any reference to the brain – but he provides a wholly new angle and point of access to the insights first offered in the Buddha’s Middle Way 2500 years ago.

It is also not an oversimplification, as some allege, to generalise about dominant features of one hemisphere or another, given that each hemispheres has evolved specialised functions and dominates over the other hemisphere with regard to those functions by inhibiting the other hemisphere. In many ways the two hemispheres do duplicate potential functions, but in practice it is their specialisations that dominate and affect our mental states and behaviour.

McGilchrist’s book is rich, readable, but also heavily referenced and academically serious. It combines the merits of science with art. If you read nothing else this year, read it.

Links

My detailed review of ‘The Master and his Emissary’

Alternative detailed review by Arran Gare

Amazon page for ‘The Master and his Emissary’

My book ’Middle Way Philosophy 1′ (endorsed by Iain McGilchrist, and including sections discussing the impact of McGilchrist’s work on Middle Way Philosophy)