Robert M. Ellis's Blog, page 2

December 14, 2013

Middle Way Philosophy 3: The Integration of Meaning – now out

The third volume of the ‘Middle Way Philosophy’ series is now  available. This volume builds on the embodied meaning thesis of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson and includes an explanation of this revolutionary approach to meaning, uniting cognitive and emotive meaning (e.g. dictionary meaning and ‘meaning of life’). It also makes extensive use of Jung’s theory of archetypes and integration framework. Relating these inspirations to Middle Way Philosophy, it puts forward the integration of meaning as a practice of moral significance making a contribution to objectivity. This shows the value of the arts as providing greater resources of meaning in our lives, which we may then draw on when developing our moral and factual beliefs.

available. This volume builds on the embodied meaning thesis of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson and includes an explanation of this revolutionary approach to meaning, uniting cognitive and emotive meaning (e.g. dictionary meaning and ‘meaning of life’). It also makes extensive use of Jung’s theory of archetypes and integration framework. Relating these inspirations to Middle Way Philosophy, it puts forward the integration of meaning as a practice of moral significance making a contribution to objectivity. This shows the value of the arts as providing greater resources of meaning in our lives, which we may then draw on when developing our moral and factual beliefs.

For more information, previews and purchase go to this page. 30% reductions currently available.

October 31, 2013

When to Intervene?

A new post over on the Middle Way Society site inspired by Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s ‘Antifragile’: link

October 18, 2013

Jan Smuts and Holism

I’ve just come across an excellent video clip for illustrating how easily an abstract metaphysical idea can be manipulated for almost any end (see link). In this case it serves a political end in supporting the dominance of one racial group over another. The term ‘holism’, like that of ‘nature’, is so vague that its connotation of ‘everything’ can be applied easily to support anything.

October 15, 2013

Franciscan saintliness

A new blog post over on the Middle Way Society on how we can make sense of the virtues of saints together with their belief in metaphysics. See http://www.middlewaysociety.org/franciscan-saintliness/

September 29, 2013

A tale of two metaphors

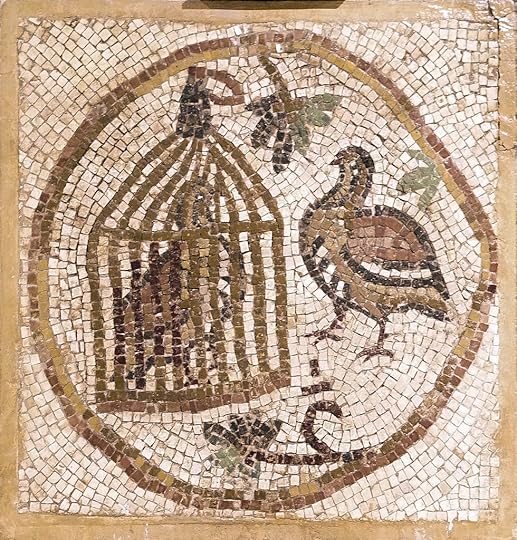

All our thinking depends on metaphors. The work of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson explains the way in which we build our cognitive models on a particular metaphor, which is mapped onto a physical experience schematised into our neural connections. For example, the picture here illustrates an old Platonic cognitive model for the mind or soul in relation to the body: the body as a cage in which the otherwise free mind is constrained. It never seemed to occur to anyone using this metaphor that our experience of being imprisoned is a physical one, and we’d need a body to even experience what it meant to be released from a cage. Nevertheless, a good deal of Plato’s philosophy depends on this metaphor.

All our thinking depends on metaphors. The work of George Lakoff and Mark Johnson explains the way in which we build our cognitive models on a particular metaphor, which is mapped onto a physical experience schematised into our neural connections. For example, the picture here illustrates an old Platonic cognitive model for the mind or soul in relation to the body: the body as a cage in which the otherwise free mind is constrained. It never seemed to occur to anyone using this metaphor that our experience of being imprisoned is a physical one, and we’d need a body to even experience what it meant to be released from a cage. Nevertheless, a good deal of Plato’s philosophy depends on this metaphor.

Plato’s basic mistake here is one that we are all prone to: of adopting just one basic metaphor and assuming that it is the final word. A ‘stuck’ metaphor is what one might otherwise refer to as a metaphysical belief. As long as we take them provisionally, however, metaphors are also the only way in which we can build up an understanding of anything. Very often, if you’re trying to explain something abstract, people only ‘get it’ when you use a metaphor. That means they’ve found a way of making it meaningful in relation to their wider bodily experience. Metaphors tend to come in connected groups, too (Plato didn’t just use the one about the soul in a cage, but also the soul as a charioteer, and many others). We can reinforce one metaphor with others, or challenge one metaphor with a different one. Perhaps the major difference between creative philosophy and mere analysis is that creative philosophy works with metaphors, pulling them together, testing out compatibility and incompatibility, whilst mere analysis just works away doggedly within one cognitive model on the assumption that it is right.

One crucial point in Middle Way Philosophy is that a belief is not ‘merely relative’ because it’s dependent on a metaphor, any more than it’s absolutely true because it’s hit the right metaphor. Some metaphors provide more adequate models for interpreting conditions than others do. The better ones can link together a great many other metaphors, as well as explaining a wide range of experiences. We can stretch metaphors to make them bigger by linking them with others, and the more provisionally we are holding the metaphor, the easier it is to do this.

So, here is a challenge to Middle Way Philosophy that I’ve been reflecting on. There is one key metaphor of the Middle Way, which relates to our experiences of following a path and of balancing: but is this metaphor being relied on too much? How can this metaphor be provisional when it is also so all-encompassing?

I have two linked responses to these linked questions. One is that Middle Way Philosophy doesn’t just depend on the metaphor of the Middle Way, but also that of integration. Another is that the bigger and stretchier a metaphor is, the more provisional it is. Middle Way Philosophy is not an ultimate explanation, but at the same time it is the kind of explanation that becomes more adequate the more it encompasses.

Firstly, then, the metaphor of the Middle Way and that of integration. These two models offer rather different models of thinking, but they are still linked. Integration is basically the Middle Way inside out. Whilst the Middle Way is a negative model that takes our motivation for granted and just tells us that there are metaphysical traps to avoid on either side, integration takes the things on each side more positively, suggests that they do themselves have motivating power, and that both the energy and the metaphors on either side can be positively incorporated into a whole The two metaphors complement each other enormously and yet remain compatible. Without the rigour of the Middle Way, integration models can get rather naïve and new-agey; but without integration, the Middle Way can get rather dry and negative.

Would it be possible to combine the two metaphors? Well, here’s an attempt. Suppose you’re captain of a ship heading through a dangerous strait between two rocks. Some of your passengers want to go straight on, but others want to pick up friends from the rocks on either side. So, you do head straight on, but not before you have picked up further passengers and rescued them from the rocks on either side. This requires both courage and skill. Once you’ve picked up all the passengers from both sides, everyone can be united in urging you onwards through the rest of the strait.

This combination of metaphors illustrates the way that even metaphors that at first seem separate can be combined and stretched. That’s one reason why I’m interested in studying even religions that seem to have a heavy metaphysical emphasis, like Islam, and, metaphorically speaking, picking up the passengers from that rock too. I want to argue that the more a given metaphor can explain the strengths of others in that way, without getting sucked into the assumption that any one metaphor is final, the more justified confidence we can have in that metaphor. If a given approach can offer responses that account for the successes other metaphorical approaches, rather than simply rejecting them as wholly wrong, it provides the basis of a bigger and more adequate metaphor.

I think Middle Way Philosophy is like this. That’s one of the reasons why it is so all-encompassing: it needs to be able to account for the insights available from different traditions and from different specialisms. However broad it is, though, to remain provisional it must be fallible. If someone else can come up with a better theory that explains all the things Middle Way Philosophy explains and does all the things it does: explaining the nature of objectivity, providing a justifiable ethics, resolving the absolutism/ relativism split, combining theory with practice, facts with values, the religious and the secular, art and science, whilst taking into account the scientific evidence for things like embodied meaning, the splits in the brain and our cognitive biases, then I will drop this theory and come and help them on theirs. Theories based on particular metaphors can be superseded – but they have to be superseded in doing the job that they set out to do, explaining both the successes and failures of the theory to be superseded.

Picture: Byzantine metaphor for the soul by Ken & Nyetta (Wikimedia Commons). Picture (only) freely reproducible under Creative Commons licence.

September 12, 2013

The Middle Way Society

We’re finally under way with a society to promote the Middle Way! At the end of the Middle Way Study Retreat held in August, all the participants agreed to create a society to promote the study and practice of the Middle Way. You can now read about it on our website, http://www.middlewaysociety.org .

Why a society? Well, it seems far too important to be left to just one person. I want to find as many people as possible who share that general orientation and work with them. There are lots of people who are looking for a coherent way of understanding what our values ought to be that goes beyond social convention and individual choice, now that the dogmas of religion and authoritarian politics no longer hold sway. The Middle Way could help them, but the message just isn’t getting across sufficiently.

The purpose of the Middle Way is practical, and it can provide a clearer rationale for a wide range of practices, from meditation and the arts through to critical thinking, that can help to open up the clenched obsessiveness of the egoistic left hemisphere that thinks it has the whole story. It can also provide a distinctive approach to those practices, that involves recognition that what makes any of them effective is a balanced flexibility of perspective.

I wanted to start a new organisation, because there is currently no organisation clearly devoted to the Middle Way as such, the Middle Way as a genuinely universal principle rather than just an aspect of Buddhism. There are Buddhist organisations, but these all too often put the traditional metaphysical beliefs of Buddhism first and the Middle Way a poor second, even though there are many good things that they do. Even Secular Buddhism, although it provides a meeting point for people interested in Buddhism who are prepared to challenge the tradition, does not have a clear rationale for really focused action. So although I will remain in contact with Secular Buddhism, the clear pursuit of the Middle Way is far more important.

We want to concentrate on quality of membership rather than just having lots of people vaguely signed up on the web. To that end, of course there will be web discussions, but we also want to hold regular retreats for detailed study and practice. We’d like to hold talks in different localities and support local groups.

All readers of this blog are invited to visit the site and to subscribe to the society. It’s an opportunity to participate in an exciting new venture – the living of a new practical philosophy that takes the best from religion whilst being clearly opposed to religious metaphysics.

September 4, 2013

Is dogma adaptive?

Why do human beings so often get stuck in fixed beliefs that are no longer adequate to the situation? Why do we have metaphysics at all? This is a question I have been considering for a while, not in expectation of ultimate answers, but particularly thinking in terms of the model offered by evolutionary adaptation. Whilst I don’t think evolutionary theory can explain everything, and there are disputable variations within it, it does seem to provide a good explanation of some key conditions. In evolutionary terms, then, human dogma must have some sort of adaptive value. Yet central to my thesis in Middle Way Philosophy is the idea that metaphysics and dogmatism are maladaptive – not in purely evolutionary terms, but certainly in terms that should have some sort of relationship to evolutionary theory. How can I account for this tension?

Why do human beings so often get stuck in fixed beliefs that are no longer adequate to the situation? Why do we have metaphysics at all? This is a question I have been considering for a while, not in expectation of ultimate answers, but particularly thinking in terms of the model offered by evolutionary adaptation. Whilst I don’t think evolutionary theory can explain everything, and there are disputable variations within it, it does seem to provide a good explanation of some key conditions. In evolutionary terms, then, human dogma must have some sort of adaptive value. Yet central to my thesis in Middle Way Philosophy is the idea that metaphysics and dogmatism are maladaptive – not in purely evolutionary terms, but certainly in terms that should have some sort of relationship to evolutionary theory. How can I account for this tension?

I have been stimulated in thinking about this recently by reading The Embodied Mind by Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. First published in 1991, but I suspect since then largely ignored by a scientific and philosophical world whose models it seriously challenges, this extremely interesting book is one of the few I have come across that explicitly uses the Middle Way in a way that is directly applied to modern scientific and philosophical debates. It does so in relation to both cognitive science and biology, which it juxtaposes with some direct bits of traditional Buddhist material about conditionality. Though the Buddhist bits are treated in an uncritical way somewhat at variance with the extremely thoughtful use of scientific models, the result is nevertheless well worth a read. However, I’m not focused here on fully reviewing this book, more with pulling out a few useful elements.

One of the sections I found interesting in this book is concerned with the whole question of what adaptivity consists in. An unreflective approach to adaptivity by a scientific cognitivist is likely to make two major assumptions, both of which are questionable:

That ‘adaptation’ by either an individual organism or a species occurs against an environmental background that is understood in isolation from the organism’s adaptation

That ‘adaptation’ should be understood in terms of optimal fitness. The optimally fit organism will survive better than the less fit one.

Both of these assumptions involve the idea that scientific theory just represents a state of affairs ‘out there’, rather than fully taking into account the complex and indeterminate relationship between models, actions and feedback as an organism not only responds to the world it encounters, but also shapes that world. The scientific observer similarly shapes the world of theory in the process of creating the theory. Adaptation, then, cannot just consist in fitting into an environment well, but also changing mental models of that environment and the environment itself. This adaptation also cannot just be a matter of finding one possible optimally ‘fit’ solution. There a lots of possible solutions, and evolutionary pressures may well operate much more negatively just by weeding out the grossly unfit, leaving both the highly adapted and the mediocre to reproduce and flourish. Genetic variation is often apparently random and results in changes that are evolutionarily neutral, or the side effects of complex interplays of genes may result in helpful adaptations being accompanied by maladaptations.

Varela, Thompson and Rosch give a good analogy for this. Imagine that a man goes to buy a suit. If we think only in terms of optimal fitness, he will just go to a bespoke tailor and get the ideal suit that completely fits him, in the ideal style that fits the social conditions. However, anyone who has ever bought a suit will know that it’s more complex than this. Bespoke suits are very expensive, so we are more likely to go to a department store and buy a ready-made cheaper suit in more or less our size, that more or less suits us. The suit that the man buys (given that he is not rich enough to buy a bespoke suit) will be sub-optimal, one of a number of possible solutions in a situation of complex economic, social and corporeal conditions. He could have bought any of a number of possible suits, and he ended up with one that was OK. The authors suggest that evolutionary adaptation is much more like this than like bespoke tailoring.

So, to return to the question I started with: how might dogma be adaptive? I would suggest, because it was, and still is, one of a number of suboptimal solutions that more or less fitted an environment. The kind of environment that it sub-optimally fits is one dominated by group consciousness. A group of hunters in pursuit of deer, or even a group of footballers on a team, do not want too much innovation: above all they want loyalty and reliability. So this kind of situation creates pressures towards fixed models of our environment, because this model will reliably correspond with that of our fellows. Metaphysics is born – first in predominantly religious and political forms that help to maintain the power of leaders, then later in negative forms such as scientism, that help to maintain group loyalty even in a group that is theoretically devoted to rigorous investigation.

However, at the same time, there is another kind of sub-optimal adaptation in human history. Original thinkers who are prepared to create different models may also sometimes have their day. They may, for example, recognise an impending climatic catastrophe or the likely loss of a food source and prompt their society to make effective preparations for it. Later on, they may be Aristotles or Galileos or Einsteins, offering a new model that differs greatly from what preceded them. These people also benefit their societies, so societies that at least tolerate them, and sometimes listen to them, are more likely to be successful in the long run.

So far in human history, though, I would hypothesise, it is the first kind of sub-optimal adaptation that has had the upper hand. The faster the environment changes, though, and the more we contribute to changing it through innovation, the harder it becomes for the metaphysical world view to be effective. There have been times in the past – such as the Buddha’s India or Ancient Greece – where individuals have been able to come to the fore and challenge group-consciousness, and where the balance and integration between brain hemispheres (as tracked by Iain McGilchrist) improved. We may also be in such a position now, where it is flexible individual thinking capable of defying metaphysical assumptions that is most needed so that we can address rapidly changing conditions. Flexible, integrated thinking does not result in ideal solutions, but it does improve what we have, and may be crucial to our survival.

Picture: Evolution 1 by Latvian (Wikimedia Commons). Picture only re-usable under Creative Commons Licence.

July 18, 2013

The Middle Way to Anarchy

Recently I’ve been writing educational materials on anarchism, which has made me think again about this raft of ideological approaches. It is possible to make all kinds of claims for anarchism, depending on how one defines or understands it: for example, either that it is a threat to a peaceful society, or the reverse that it is the most peaceful ideology in existence; that it is the only true road to human freedom, or that it is the ultimate threat to freedom. It also seems to me that defined in one way, everyone is an anarchist, and defined another way, nobody is. If you think of anarchism as a gradual intention to minimise unnecessary interference by the state in people’s lives, with no government merely as an remote ultimate goal, then everyone is an anarchist. If on the other hand you think of anarchism as a revolutionary wish to immediately destroy all coercive sources of order, then really nobody is an anarchist, least of all those who call themselves anarchists when their wishes are more closely examined.

threat to a peaceful society, or the reverse that it is the most peaceful ideology in existence; that it is the only true road to human freedom, or that it is the ultimate threat to freedom. It also seems to me that defined in one way, everyone is an anarchist, and defined another way, nobody is. If you think of anarchism as a gradual intention to minimise unnecessary interference by the state in people’s lives, with no government merely as an remote ultimate goal, then everyone is an anarchist. If on the other hand you think of anarchism as a revolutionary wish to immediately destroy all coercive sources of order, then really nobody is an anarchist, least of all those who call themselves anarchists when their wishes are more closely examined.

All this sounds familiar to me from my philosophical explorations of the function of metaphysical ideas, like those of God, freewill, determinism, materialism etc. Anarchism is just another of those remote idealisations that have no genuine connection with people’s experience. Our experience is actually of societies in which there are varying degrees of coercion going on, not of a society with final and complete freedom, absolute equality, and no more government. In the mixed up context in which we live, the only function of such idealisations is to support dogmatic actions that are ill-adapted to their environment.

This can be seen, not only from the remote and idealised nature of the conception of anarchy itself, but from its degree of abstracted adaptability. Like God, anarchy can be all things to all people. Every other ideology has its own version of anarchy: there are anarcho-capitalists at the ultra-extreme end of libertarianism, tribal anarchists who are ultra-conservative, anarcho-syndicalists and mutualists who take socialism as their departure point, anarcho-ecologists, and anarcho-communists who offer a slightly more coherent account of communism (than Marx) without the determinism. For all of these ideologies, the appeal to ultimate anarchy is little more than the source of an extra dogmatic edge to their libertarianism, conservatism, socialism or whatever. I suppose out of all the range of anarchisms, it is mutualism that earns my respect most, because it is largely concerned with directly constructing communities or institutions that actually help people to support each other without an appeal to authority, such as credit unions or workers’ co-operatives.

At the same time, again like God, I don’t think that the idea of anarchy is meaningless. It is symbolically important precisely because, for some people at some times, it does stand for or evoke important experiences. It seems to stand symbolically for integration, particularly as understood socially and politically. The final state of society that so inspires anarchists is one in which there is no conflict, and therefore no reason for intervention by authorities. However, to bring about a lessening of conflict, as I have argued a good deal elsewhere, it is integration that is required, with psychological integration meshing with social integration. Our ability to avoid conflict with others depends on our ability to avoid conflicts within ourselves.

So here is perhaps the biggest naivete in Anarchism: it is often described as “having an optimistic view of human nature”, such that, when the imposition of authority from outside is removed, human beings will “naturally” start to behave in a peaceful and co-operative way. This is not naïve because it’s impossible: I don’t think it is impossible, but there’s nothing “natural” about it. For people to co-operate (i.e. be integrated) in such a way, they need to be integrated in themselves, and their integration is a matter of degree, rather than a matter of being “naturally” good or bad. So the state of anarchy could only be achieved, as a matter of degree, by a similar degree of integration amongst all the individuals in the world. We could only work towards achieving it by the practice of the Middle Way. So the way to work towards an ideal state of anarchy involves avoiding metaphysical beliefs such as ones about human nature being “naturally” rational or “naturally” corrupt, or any other such absolutist dogmas.

So, along with pretty much everyone else, I’m an anarchist in a sense. I don’t expect that we will ever reach a state where stable anarchy without the need for government will occur, but I’m happy for that idea to have archetypal importance so long as people don’t start believing in it and using it as the basis of dogmatic judgements. That’s when the harm starts creeping in, whether its from the Angry Brigade or from the free-market egoism of Ayn Rand. I think there is a possible road to such a state of virtuous anarchy through gradual integration, just as there is to enlightenment or God or any other such idealisation. And everyone could be an anarchist in this sense without it making much difference to our political judgements, as political judgements are about what we do, now, in experience, not about such remote ideals.

July 15, 2013

Cognitive biases

June 30, 2013

Disruptive innovators

A couple of days ago, I found myself at a Free Schools conference listening to Michael Gove, the English Minister for Education. I have little experience of listening to leading politicians live as opposed to through the media, so it was interesting to see how skilfully he worked his audience. A good deal of flattery and a lot of points containing an element of truth, but entirely one-sided and missing the other side of the picture. This is, I suppose, how politicians are successful: they can’t either please all of the people all of the time, nor can they please none, but they are able to reinforce the passion of the converted, and charm a fair section of the unconverted into at least temporary suspension of their critical faculties.

I have little experience of listening to leading politicians live as opposed to through the media, so it was interesting to see how skilfully he worked his audience. A good deal of flattery and a lot of points containing an element of truth, but entirely one-sided and missing the other side of the picture. This is, I suppose, how politicians are successful: they can’t either please all of the people all of the time, nor can they please none, but they are able to reinforce the passion of the converted, and charm a fair section of the unconverted into at least temporary suspension of their critical faculties.

The creators of Free Schools, said Mr Gove, are “disruptive innovators” who are doing a favour to society, motivated by love for children. Here the rhetoric went into overdrive, as he compared the creators of Free Schools to Martin Luther and then Martin Luther King. I was almost expecting him to compare them to Jesus himself, but of course he didn’t want to risk causing offence to the faithful. Of course, we will meet ideological resistance, he said, but innovation is always disruptive and competes with older ways of doing things. Those who meet disruption as a result of innovation are challenged to smarten up their own act.

Although the rhetorical excesses only registered a grim smile with me, the core argument here is one with which I can sympathise. I would not have been sitting there, a potential creator of a sort of Free School myself (the Virtual Sixth Form College), unless it did. The basic idea of innovation being beneficial to society is straight out of the pages of John Stuart Mill. Mill argued powerfully that we should be given whatever freedom we require to innovate, for if we are not able to innovate then society cannot address the conditions it finds itself in. However, he also set a clear limit on that freedom: we should be free to innovate provided we do no harm to others or to their interests.

That, I think, is the question that at least some of the Free School creators around me may have needed to ask themselves with a little more care. If one sets up a new Free School in a locality which already has enough (or nearly enough) school places, and (as is certainly the case with some free schools) the justification for the new school is only one of increased parental choice or better quality than existing schools in the area, then this risks greatly undermining the recruitment and the support for, and hence the quality of, other schools in the area. The interests of the children and young people are thus at least in danger of being harmed. Even if the new Free School prospers, more children may suffer worse education than gain better education.

There will obviously, though, be some Free Schools which do a lot more good than harm, particularly in a locality where there is a genuine shortage of school places overall. Here there is space to exercise the innovation and enthusiasm of the ‘Free Schoolers’ without impacting on other schools very much. The Virtual Sixth Form College, I hope, will be in a similar position, not because it will specifically be catering for one area with a shortage of sixth form places, but because it will be offering an entirely different option for sixth form education in a way that is spread evenly across the country. No one existing school or college will be adversely affected by this except to an extremely marginal extent.

But there are also wider questions that Gove failed to answer about Free Schools. If the freedom to innovate is so good, why does he not simply introduce an act of parliament to grant the freedoms given to free schools (for example, to vary the curriculum and employ teachers without Qualified Teacher Status) to all existing schools? Does he really think that the talent and enthusiasm for making use of this freedom, so evident at the Free Schools conference, is lacking in all other schools? New challenges of competition between schools would then at least take place with greater equality of opportunity.

So, as you can see, despite being a potential Free School proposer myself, I am by no means in favour of the whole of the Free Schools programme in its current form. I am very much in favour of innovation in education, which is why I wish to take advantage of this opportunity to be an innovator. However, the opportunity for innovation is in no way consistently enough applied in the system that has been created. The amount of disruption caused by innovation also cannot be left open-ended: nobody can innovate without some degree of disruption, but innovation pursued without careful regard for the full context can create an unbalanced level of disruption that does not help the education system to address conditions better. Free School proposers should not take their inspiration from Martin Luther so much as from Aristotle and the Buddha, whose radical innovations were nevertheless contextualised in a wider ethic of balance.

Picture: Michael Gove (cropped) by David R Clarke: reproducible under Creative Commons Licence from Wikimedia Commons